True grit: ingestion of small stone particles by hummingbirds in West Mexico

2022-01-07OmarMayaGarcMauricioOrtegaFloresandJorgeSchondube

Omar Maya-García, Mauricio Ortega-Flores and Jorge E. Schondube*

Abstract

Keywords: Arthropod chitin content, Arthropod digestion, Breeding season, Mineral nutritional requirements

Background

Grit, defined as small stones or tiny rock fragments, is ingested by many bird species to facilitate the mechanical grinding of ingested hard food items (Ziswiler and Farner 1972; Brown 1976; Barrentine 1980; Bishton 1986; Gionfriddo and Best 1999). However, grit can also serve as a source of minerals such as calcium (Sadler 1961; Harper 1964; Korschgen 1964; Campbell and Leatherland 1983;Adam and des Lauriers 1998). Ingestion of grit by birds has also been found to be influenced by the hardness of ingested food (Bird and Smith 1964; Mott et al. 1972;Alonso 1985; Gionfriddo and Best 1996) and by changes in mineral requirements, particularly during egg production and periods of accelerated growth (Harper 1963;Kopischke and Nelson 1966; Taylor 1970; Johnson and Barclay 1996; Reynolds 1997).

Although many different species of birds ingest grit,few research papers have documented the use of grit by hummingbirds. In these reports, different species of hummingbirds ingested materials such as wood ashes,lime dust, sand particles, and small rocks of different geological origins (Haverschmidt 1952; Verbeek 1971;des Lauriers 1994; Adam and des Lauriers 1998; Graves 2007; Estades et al. 2008; Hickman et al. 2012; See Additional file 1: Table S1 for details). Interestingly, most reports of grit ingestion by hummingbirds have been of females during the breeding season (Haverschmidt 1952;Verbeek 1971; des Lauriers 1994; Adam and des Lauriers 1998; Graves 2007; Hickman et al. 2012; Additional file 1: Table S1). As a result, some authors have suggested that female hummingbirds ingest mineral-rich grit to obtain calcium for eggshell production (Verbeek 1971; des Lauriers 1994; Adam and des Lauriers 1998;Graves 2007; Estades et al. 2008; Hickman et al. 2012).However, female hummingbirds also consume more, and higher quality arthropods (e.g. spiders) during the breeding season to provide protein for egg production and to provision nestlings (Hainsworth 1977; Montgomerie and Redsell 1980; Chavez-Ramirez and Down 1992; Stiles 1995; Murphy 1996; Rico-Guevara 2008), so grit could also be used to aid in the mechanical digestion of these arthropods (Ziswiler and Farner 1972; Brown 1976; Barrentine 1980; Bishton 1986; Gionfriddo and Best 1999).

Our objective was to quantify the number of grit particles in the stomachs of several species of hummingbirds and to explore the possible function of grit ingestion by hummingbirds. Specific objectives were to determine:(1) the extent to which hummingbirds ingest grit and how many grit particles are present in their stomachs, (2)if grit ingestion varies seasonally, (3) if there are differences in the use of grit by sex (females vs. males) and age classes (juveniles vs. adults), and (4) if there is a relationship between the number of grit particles in hummingbird stomachs, the quantity of arthropods ingested, and the chitin content of ingested arthropods.

Because the amount of arthropods ingested by hummingbirds changes seasonally with the availability of food resources at our study site, we expected hummingbirds to ingest more grit when they ingested more arthropods. In addition, because the number of grit particles increases in response to food hardness in other species of birds (Bird and Smith 1964; Mott et al. 1972;Alonso 1985; Gionfriddo and Best 1996), we expected that hummingbirds that consumed arthropods with greater chitin content would have more grit particles in their stomachs than those that feed on softer arthropods.Finally, because females ingest more arthropods than males during the breeding season to meet the higher nutritional and energy requirements of producing eggs and parental care (Hainsworth 1977; Montgomerie and Redsell 1980; Chavez-Ramirez and Down 1992; Stiles 1995; Murphy 1996; Rico-Guevara 2008), we expected those female hummingbirds would have more grit particles in their stomachs than adult males.

Methods

Study site

Our study was conducted at the Nevado de Colima National Park (NCNP) in Jalisco, Mexico. Nevado de Colima is an inactive high-altitude volcano (4260 m a.s.l.)located at the western end of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt (19° 33′ 45″–19° 30′ 40″ N, 103° 36′ 30″–103°37′ 30″ W; INEGI 2011). The climate in the region is highly seasonal (CONANP 2006, 2017). Our study site was located at 3194 m a.s.l. and consisted of subalpine scrublands (dominated by plants of the genusSalvia

,Ribes

, andFestuca

), some scattered alders (Alnus

) on exposed ridges, and pine and fir forests (Pinus

andAbies

)located in ravines (Schondube 2012). The most important flowering plants that hummingbirds feed on includeSalvia elegans

,S

.gesneriflora

(Lamiaceae),Ribes ciliatum

(Saxifragaceae),Senecio angulifolius

(Asteraceae), andPenstemon roseus

(Plantaginaceae) (Schondube 2012).Fieldwork

We sampled hummingbirds three times over a one-year period. Our sampling corresponded with the three climatic seasons in the region, including (1) a rainy season from June to October, (2) a cold-dry season from November to February, and (3) a warm-dry season from March to May (CONANP 2006, 2017). We selected this sampling scheme because weather conditions and the availability of floral nectar and arthropods varied widely among these three seasons (CONANP 2006, 2017). We sampled during May and September 2016, and February 2017.During each sampling period, we captured hummingbirds using 10 mist-nets (12-m long, 24-mm mesh) for three consecutive days. Mist-nets were opened at sunrise and closed after 6 h. Net rounds were conducted every 5 min. We located the mist-nets within a 2 ha area, and their location remained constant during the study. We identified all captured birds and recorded their age and sex using plumage characteristics and bill striations (Williamson 2001; Howell 2002; Russell et al. 2019). Additionally, for the Mexican Violetear, the only species that did not present a clear sexual dimorphism in plumage at our study site we used wing chord length and bill tip serrations to determine their sex (Rico-Guevara et al. 2019).Data on wing chord differences among sexes for this species was obtained from a 30-year hummingbird banding program located in the same region. We define females as those individuals with a wing chord < 60 mm, and males as those individuals with a wing chord > 63 mm (Contreras-Martínez personal communication).

Stomach content analysis

We obtained the stomachs of hummingbirds collected as part of an independent stable isotope project conducted at our study site (n

= 6 in May 2016,n

= 8 in September 2016, andn

= 37 in February 2017). That study collected blood, liver, pectoral muscle, and bones to extract collagen, and allowed us to use the stomachs. The remaining feathers, skulls, and tongues were deposited at the collection of the Functional Ecology Laboratory of IIES,UNAM. Samples were collected with permission from the Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales,Mexico (SGPA/DGGFS/712/2767/14). All collected birds were humanely euthanized by carefully placing their heads inside a small vial that contained a cotton ball soaked in isoflurane, following the guidelines to the use of wild birds in research (Fair et al. 2010), and their stomachs were placed in plastic vials with saline solution (0.8%NaCl) and frozen in liquid nitrogen until processed in the laboratory. The time between hummingbird capture in the nets and stomach freezing was less than 20 min.Because soft arthropods require 3–4 h to be digested completely by hummingbirds (Remsen et al. 1986), this time frame allowed us to quantify stomach arthropod content at the moment of capture. The species sampled were: Mexican Violetear (Colibri thalassinus

), Amethyst-throated Mountaingem (Lampornis amethystinus

),White-eared Hummingbird (Basilinna leucotis

), Rivoli’s Hummingbird (Eugenes fulgens

), Broad-tailed Hummingbird (Selasphorus platycercus

), and Rufous Hummingbird(S. rufus

). The number of individuals collected at each season differed due to variation in capture rates among seasons, and due to restrictions on collecting permits(maximum of 10 individuals per species per season).We analyzed hummingbird stomachs in the lab to determine the number of grit particles they contained.Stomachs were thawed and dissected, and their contents removed. We quantified grit particles by carefully separating them from the arthropod remains in hummingbird stomachs using a stereoscopic microscope (AmScope, 7–45 × binocular stereo zoom microscope). We described the color and shape, and weighed and measured grit particles. To determine their size,we determined the grit area by taking a picture of each grit particle on top of a millimetric grid. Images were analyzed using ImageJ (National Institute of Health,NIH Version v1.32j). Because the role of grit as either a grinding agent or nutritional supplement depends upon its hardness and solubility in the digestive tract (Meinertzhagen 1954; Myrberget et al. 1975; Gionfriddo and Best 1999), we determined grit hardness. We did this by pressing each grit particle twice with fine-point reverse action tweezers. This kind of tweezer allowed us to generate a standard pressure on the grit particle and separate them into two hardness categories: hard (did not break)and soft (did break into smaller pieces).

Physical and chemical characterization of grit particles

We used scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy (Tabletop Microscope Hitachi, Model TM3030Plus) to perform the physical and chemical characterization of the grit particles. Because soft grit broke into tiny particles, we were only able to analyze the hard grit particles. Of these, due to the limitations imposed by the method, we were able to analyze only the largest hard grit particles (diameter of 0.5–1 mm,n

= 5). Analyses were carried out in the Microanalysis Laboratory of the Geophysics Institute,UNAM.Ingested arthropod biomass and chitin content

We separated all arthropod remains into those that were identifiable (arthropods partially fragmented) and those that were not (very fragmented arthropods) using a stereoscopic microscope. We identified recognizable arthropods to the taxonomic level of order following Triplehorn and Johnson (2005). To determine the biomass of ingested arthropods (g dry mass), we dried both identifiable and unidentifiable arthropod samples at room temperature for 3 h and then weighed them using an analytical balance (Ohaus Adventurer, capacity/readability of 110 g × 0.001 g). Chitin content (percent dry mass)of the different identified arthropod orders was obtained from Rothman et al. (2014). We estimated the mean chitin content of arthropods by averaging the percent chitin content of the different arthropod orders present.

Data analysis

We used different analyses to test our main hypotheses on the use of grit particles by hummingbirds. First, we compared the number of grit particles present in hummingbird stomachs among species using a Kruskal–Wallis test (Zar 1999). We used a non-parametric test because our data did not present a normal distribution.In view of the fact that we did not find grit particles in the stomachs of hummingbirds during the warm-dry season,and due to the small sample size of the rainy season, this analysis was limited to our data for the cold-dry season.

Second, we used a generalized linear model (GLM) to assess whether the number of grit particles (response variable) varied among seasons, and between age and sex classes. In this model, we include season (warm-dry,rainy, and cold-dry seasons), age (adult and juvenile individuals), and sex (female and male individuals) as categorical explanatory variables. We select for this analysis the data of all 25 male and 21 female individuals sampled,excluding data from the 5 individuals whose sexes were unknown. Due to our small sample size, we created a 0–1 binary response variable in which 0 represented the absence of grit and 1 represented the presence of grit,and fitted our model with a Binomial distribution and a logit link function. Additionally, we used the adjusted maximum likelihood estimator for reducing biases of the Binomial logistic regression parameters (following Firth 1993).

Third, because the two response variables of arthropod ingestion (i.e. the biomass of arthropods ingested and their chitin content) presented different distributions, we ran two GLMs with the number of grit particles as the explanatory variable, whereas the response variables differed. For GLM 1, we used the biomass of ingested arthropods (g dry mass) as the response variable and a normal distribution with an identity link function.For GLM 2, we used the chitin content of arthropods ingested by hummingbirds (percent dry mass) as the response variable, and a Poisson distribution with a Log link function. In both models, we only included the data from those individuals whose stomachs presented grit particles (n

= 12 for GLM 1, andn

= 8 for GLM 2; Additional file 1: Table S2).Finally, we performed some tests to search for differences in the arthropod content and grit particles characteristics between individuals of both sexes. Since we only had a male individual, we use the data of the females to construct a confidence interval to compare it against the male values using a one-samplet

-test for those variables with normal distributions (number of grit particles and the biomass of ingested arthropods), and a Wilcoxon test for non-normal distributed data (size of grit particles;Sokal and Rohlf 1995). We conducted all analyses using JMP version 9.0 (SAS Institute Inc.). Values are provided as means ± SD.Results

Characteristics of grit particles ingested by hummingbirds

Grit particles were of two types: crystal-like or opaque and non-crystalline. The average mass of grit particles was 0.057 ± 0.042 mg (n

= 50). The average size of the larger flat side of ingested grit particles was 0.52 ± 0.38 mm(n

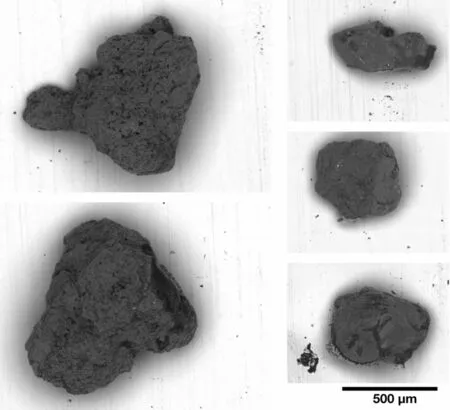

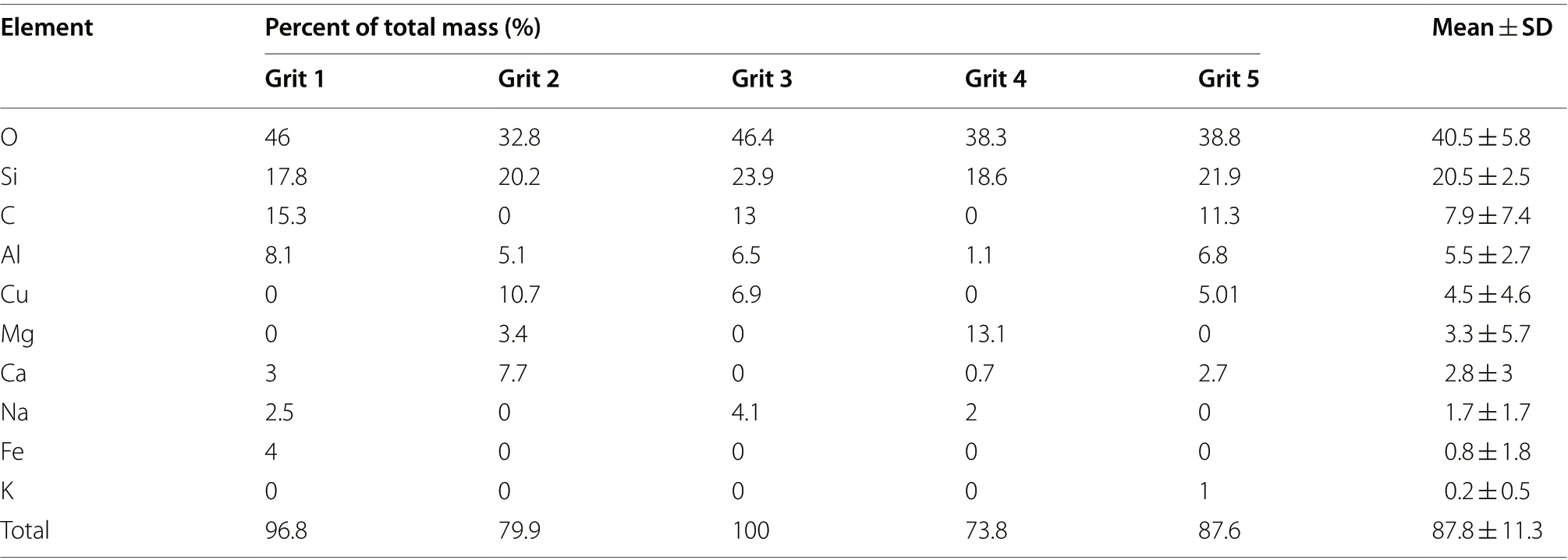

= 50). We found that 70% of the grit particles did not break when pressed with the tip of the tweezers(classified as hard, all crystal-like), whereas the other 30%broke after the first or second pressing (classified as soft,mostly opaque, and non-crystalline particles, and a few crystal-like particles).Examination of hard grit particles using both a stereoscopic and a scanning electron microscope revealed that they were black, angular to rounded, and very porous (i.e.with vesicles; Fig. 1). Additionally, spectroscopy analysis(EDX) revealed that grit particles had high concentrations of oxygen and silicon (40.5 ± 5.8% and 20.5 ± 2.5%of total mass, respectively, mean ± SD,n

= 5), and low levels of minerals such as calcium and sodium (< 10% of total mass; Table 1). Based on their physical characteristics and chemical composition, hard grit particles analyzed were classified as volcanic glasses (Sosa-Ceballos personal communication).Use of grit particles by hummingbirds

Fig. 1 Morphology of hard grit particles present in the stomachs of Mexican Violetears. All grit particles are presented at the same scale. Pictures were taken at 5 kV using a Hitachi TM3030

Table 1 Chemical composition of hard grit particles found in the stomachs of Mexican Violetears (average grit particle mass = 0.3 ± 0.1 mg, n = 5)

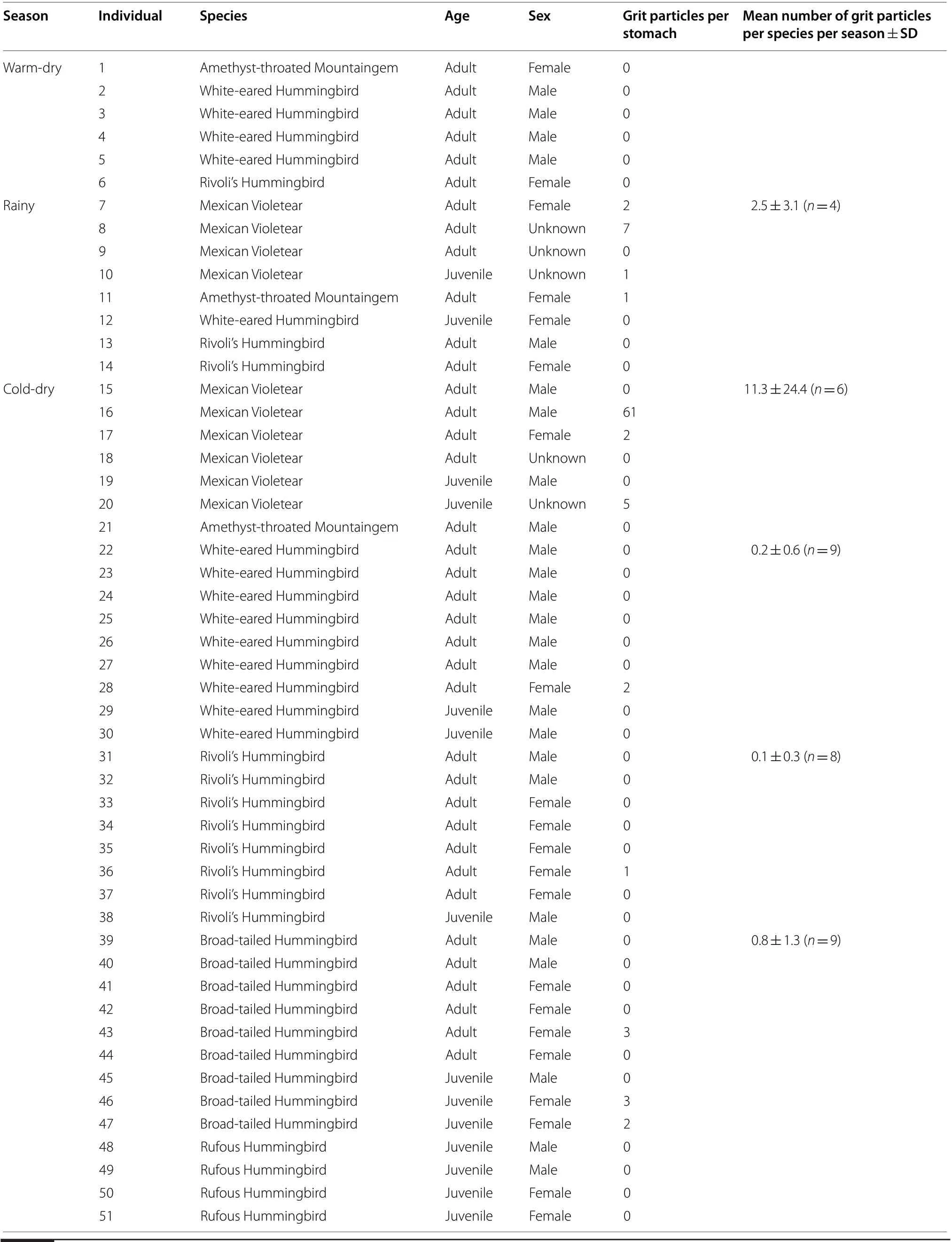

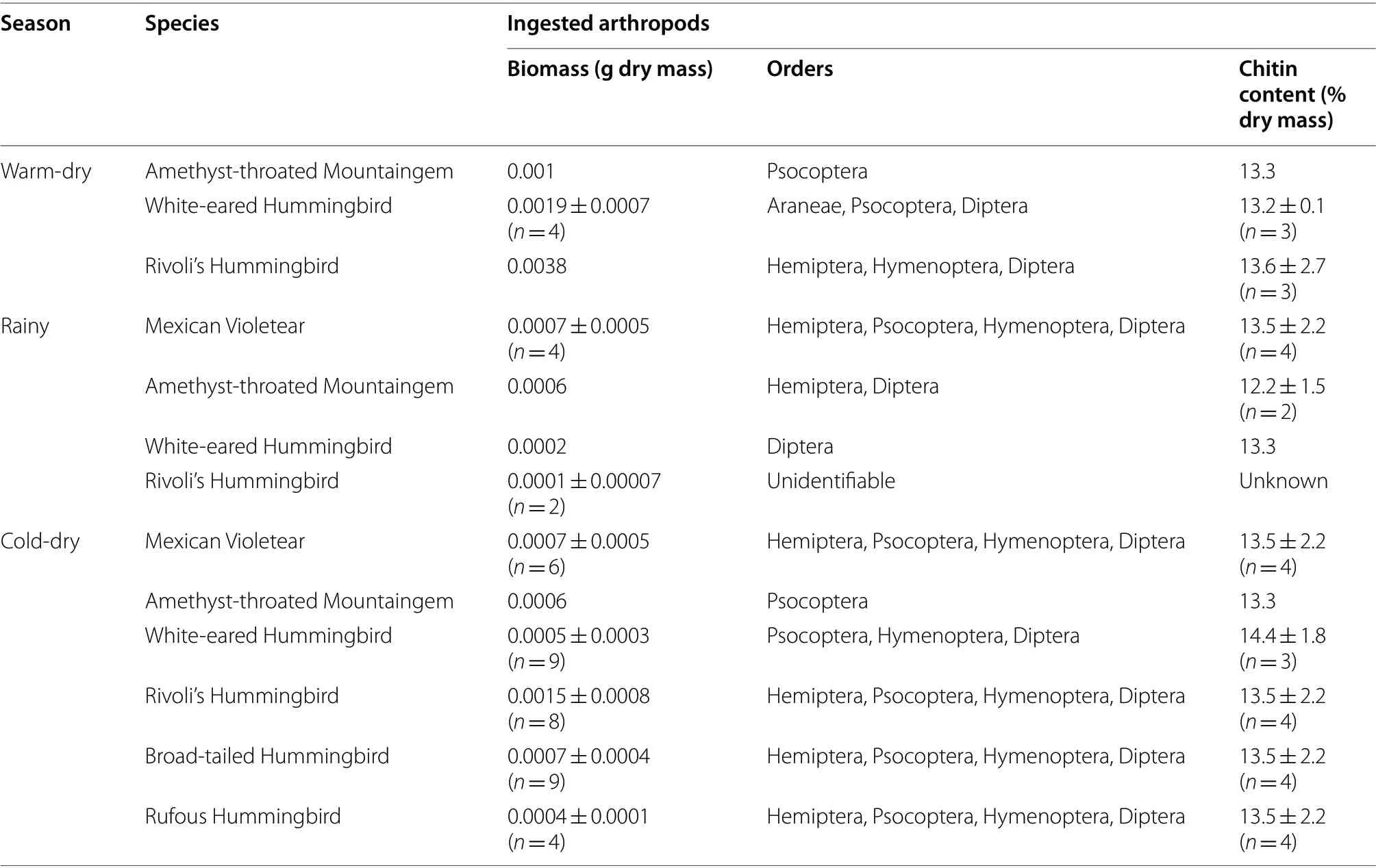

Table 2 Number of grit particles per stomach (mean ± SD for n > 1) of the different members of a hummingbird ensemble in a seasonal ecosystem of West Mexico

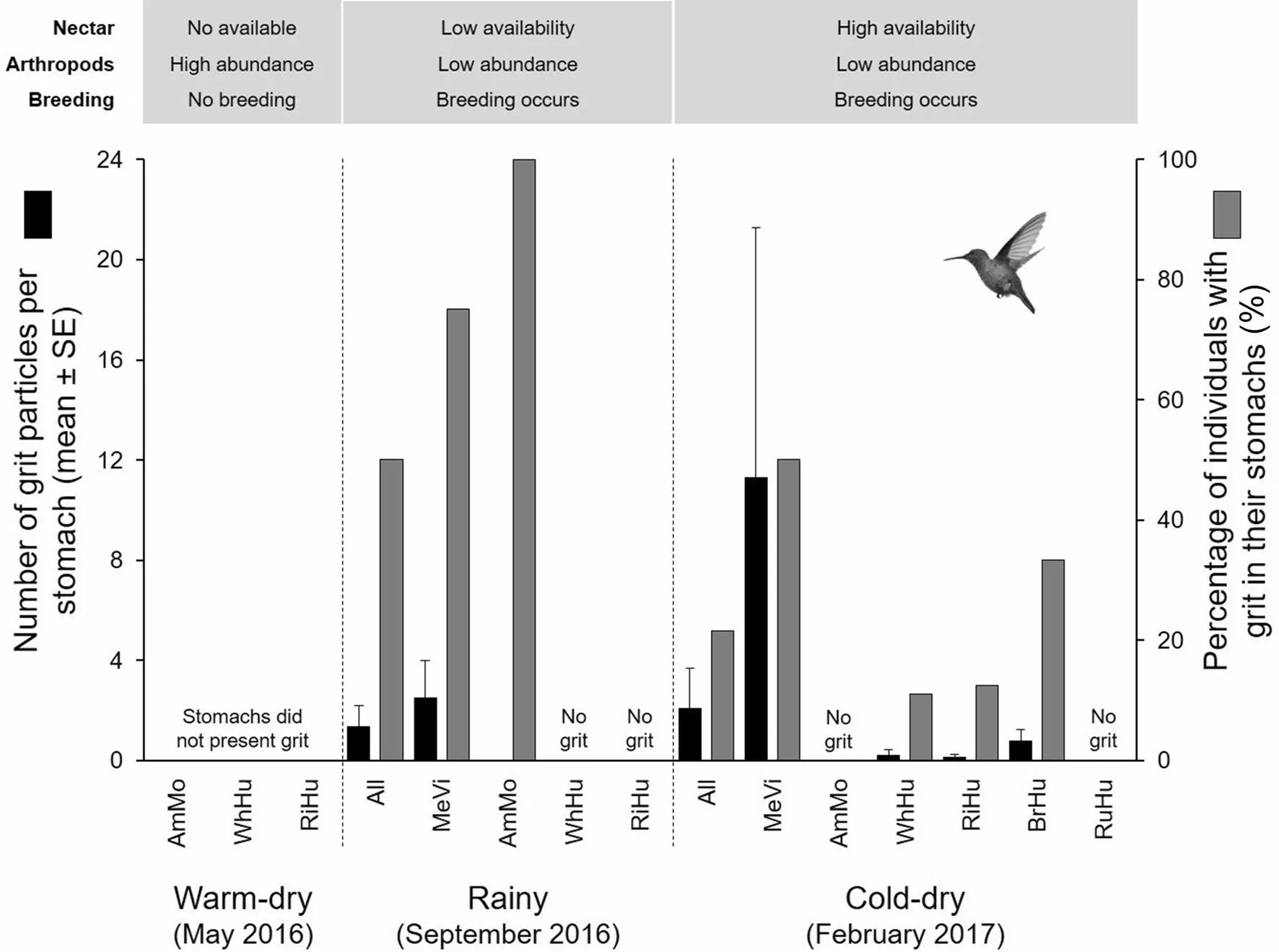

Fig. 2 Seasonal differences in the number of grit particles per stomach (mean ± SE when n > 1; black bars) and percentages of individuals with grit in their stomachs (gray bars) for all hummingbird species. During the warm-dry season, no grit particles were present in the stomachs ofhummingbirds. MeVi Mexican Violetear, AmMo Amethyst-throated Mountaingem, WhHu White-eared Hummingbird, RiHu Rivoli’s Hummingbird,BrHu Broad-tailed Hummingbird, RuHu Rufous Hummingbird, and All All species sampled per season

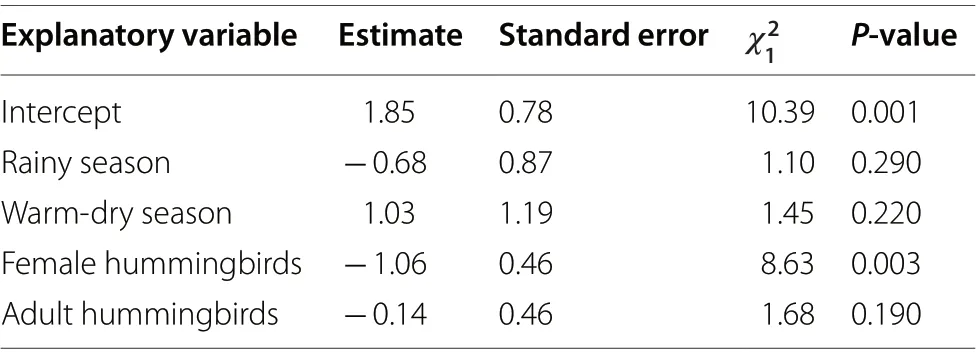

Table 3 Results of the GLM evaluating the effects of season,sex, and age on the presence of grit particles in the stomachs of hummingbirds

We found no significant differences in the average number of grit particles per stomach among hummingbird species within the cold-dry season (Kruskal–Wallis test,χ

= 4.9,P

= 0.2; Table 2; Fig. 2). However, during this season, Mexican Violetears had the highest average number of grit particles per stomach (11.3 ± 24.4,n

= 6), and the highest percentage of individuals with grit in their stomachs (50%; Table 2; Fig. 2). Finally, our binomial model showed that the use of grit particles was higher in female hummingbirds when compared to males, while adult and juvenile individuals did not differ (Table 3).Relationship between the presence of grit particles and arthropod ingestion

The biomass of arthropods ingested by hummingbirds was not related to the number of grit particles in hummingbird stomachs (estimate = 0.00001, SE = 6.99 e,χ

= 3.1,P

= 0.07). Similarly, the chitin content of arthropods ingested by hummingbirds was not related to the number of grit particles present (estimate = 0.01,SE = 0.05,χ

= 0.04,P

= 0.8). The only male that presented grit had higher arthropod biomass in its stomach(0.0014 g dry mass) than the females (0.0006 ± 0.0004 g dry mass/stomach;t

= − 4.56,P

< 0.0013). Data on the arthropods ingested by hummingbirds is shown on Table 4.Discussion

All studies that have reported ingestion of grit by hummingbirds have found that only females ingested grit (Haverschmidt 1952; Verbeek 1971; des Lauriers 1994; Adam and des Lauriers 1998; Graves 2007; Hickman et al. 2012). At our study site, we found that both female and male hummingbirds can ingest it. The use of grit particles was more frequent in females (eight of 21 sampled) than males (1 of 25 sampled). However, the only male that presented grit ingested a larger number of grit particles (61 particles) when compared to female individuals (2.0 ± 0.75,n

= 8). Although the percentage of hummingbirds with grit particles in their stomachs was relatively low (23.5%, including all hummingbirds sampled), our results suggest that the use of grit by hummingbirds is more common than previously thought. However, because of our small sample size,we were unable to determine how common is the use of grit by male hummingbirds and, as a result, the differential use of grit by male and female hummingbirds requires additional study.The use of grit by hummingbirds at our study site was seasonal, with grit in their stomachs being present only during the rainy and the cold-dry seasons. Because hummingbirds at our study site breed during both the rainy and the cold-dry seasons, these results suggest a relationship between ingestion of grit and hummingbird breeding. Others have also reported that hummingbirds only ingest grit during their breeding season (Haverschmidt 1952; Verbeek 1971; des Lauriers 1994; Adam and des Lauriers 1998; Graves 2007; Hickman et al. 2012).

Table 4 Biomass ingested and chitin content of different arthropod orders eaten by hummingbirds at our study site

During the warm-dry season, no flowers were detected at our capture site (2 ha area) and two additional surrounding areas we used to sample resource abundance located 2–4 km away from it (Maya-García and Schondube, unpublished data). The hummingbirds survived in this season by ingesting more arthropods (0.002 ± 0.001 g dry mass/stomach; mean ± SD; Maya-García and Schondube, unpublished data) than during the rainy and the cold-dry seasons (0.0005 ± 0.0004 and 0.0006 ± 0.0005 g dry mass/stomach, respectively) when several plant species were blooming, and nectar was abundant. This higher content of arthropods, while grit particles were absent from the hummingbird stomachs, suggests that the use of grit is not clearly linked to arthropod ingestion in the majority of the sampled species and that ingestion of grit particles could be associated with obtaining micronutrients as has been suggested previously (Verbeek 1971; des Lauriers 1994; Adam and des Lauriers 1998; Graves 2007; Estades et al. 2008; Hickman et al.2012).

The proportion of individuals who presented grit in their stomachs was higher in juveniles (28.5%, four of 14 sampled) than in adults (21.6%, 8 of 37 sampled), suggesting that grit ingestion could be more important for juveniles. Grit ingestion by juveniles could possibly serve two complementary roles: (1) due to their high nutritional requirements, juveniles could use grit as a source of minerals to finish their skeleton development after leaving the nest (Harper 1963; Tilgar et al. 2004; Reynolds and Perrins 2010); and (2) because arthropods are an important source of protein for tissue growth, grit particles could also be used by juveniles to facilitate the mechanical digestion of ingested prey.

The absence of significant relationships between the number of grit particles in hummingbird stomachs and the biomass of arthropods ingested by hummingbirds and ingested arthropod chitin content suggests,once again, that the primary role of grit ingestion is not related to arthropod mechanical grinding, and could be associated to obtaining minerals. However, due to the time passed between hummingbirds’ capture in the nets and the moment we excised and froze their stomachs(< 20 min), some of the soft-bodied arthropods could have been digested biasing our analysis. As a consequence, our results should be considered with caution.Curiously, most hard grit particles were found in the stomachs of Mexican Violetear hummingbirds, suggesting that the use of grit to obtain minerals may be limited in this species. Nonetheless, we need to consider that soft grit particles break easily and could dissolve in the acidic stomach of hummingbirds, limiting our capacity to find them and quantify their use.Although we found no differences among hummingbird species in the number of grit particles ingested,Mexican Violetears ingested more grit particles than other species during both the rainy and the cold-dry seasons, accounting for 90.4% of all hard particles present in hummingbird stomachs. Additionally, the only male hummingbird that presented grit particles, a Mexican Violetear captured during the cold-dry season, presented a surprisingly high quantity of 61 grit particles. This individual accounted for 77.2% of all hard grit particles present in Mexican Violetear hummingbird stomachs. These two results seem to be related to the arthropod ingestion patterns of this species. Mexican Violetears ingested more adult wasps (Hymenoptera) during the rainy and the cold-dry seasons than the other hummingbird species (19.2% and 45.5% of total arthropods present in their stomachs in both seasons, respectively; Maya-García and Schondube, unpublished data). This ingestion of hymenopterans is surprising because adult wasps have both low protein and high chitin content compared to other insect groups (Rothman et al. 2014).

Conclusions

Our results show that at the ensemble level, female hummingbirds ingested grit particles during their breeding season. This result suggests that ingested grit could have played a role as a supplement of some micronutrients, such as calcium needed for eggshell production.Although calcium content in hard grit particles was low,we were unable to analyze the elemental content of the soft grit particles and, due to the softness of these particles, we could be underestimating their ingestion. As a result, more information on ingestion, assimilation,and elemental content of soft grit particles is needed.Finally, for both male and female Mexican Violetear hummingbirds, grit particles could have the additional role of facilitating the mechanical digestion of hardbodied arthropods. Our analyses offer new insights to understand the roles played by grit in several species of hummingbirds, complementing previously published anecdotal information (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at https:// doi.org/ 10. 1186/ s40657- 021- 00298-x.

Additional file 1: Table S1. Grit ingestion by hummingbirds from the published literature. Table S2. Values used in the generalized linear models (GLM).

Acknowledgements

We thank Elisa Maya, Magdalena Valencia, Raul Valdés, Mariel Santillán,Selene Barba, Ana Torres and Luis Maya for their crucial support in the field.We want to express our gratitude to the director of the NCNP, Biol. José Villa,and his team, for their generous and invaluable support to our research. We also thank Giovanni Sosa-Ceballos and Silvestre Cardona-Melchor from the Geophysics Institute of the National Autonomous University of Mexico for carrying out the grit particles analysis. Finally, we thank Carlos Lara for their insightful comments on a previous version of this manuscript. OM-G received a Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT) doctoral fellowship(440805/270107). This paper is a fulfillment of the requirements to obtain the doctoral degree of the Graduate Program in Biological Sciences of the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: OM-G and JES; Methodology: OM-G, JES and MO-F; Data collection: OM-G, JES and MO-F; Formal analysis and investigation: OM-G and JES; Writing – original draft preparation: OM-G and MO-F; Writing – review and editing: JES; Funding acquisition: JES; Resources: JES; Supervision: JES. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Research funds were Granted to JES by PAPIIT-UNAM (IN212216).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Mendeley Data repository (http:// dx. doi. org/ 10. 17632/ rzhf2 bjw4v.1).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our methods were approved by the ethics committee of the Institute of Ecosystem Studies and Sustainability, UNAM. Permission to collect samples was provided by SEMARNAT, Mexico (SGPA/DGGFS/712/2767/14).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author details

Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas, Unidad de Posgrado, Coordinación del Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México,Edificio D, 1er piso, Circuito de Posgrados, Ciudad Universitaria, Del. Coyoacán,C.P. 04510 México D.F., Mexico.Laboratorio de Ecología Funcional, Instituto de Investigaciones en Ecosistemas y Sustentabilidad, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Antigua Carretera a Pátzcuaro No. 8701, Col. Ex Hacienda de San José de la Huerta, C.P. 58190 Morelia, Michoacán, Mexico.

Received: 25 April 2021 Accepted: 1 November 2021

杂志排行

Avian Research的其它文章

- Taxonomic revision of the Savanna Nightjar (Caprimulgus affinis) complex based on vocalizations reveals three species

- Taxonomic status of grey-headed Yellow Wagtails breeding in western China

- The composition of mixed-species flocks of birds in and around Chitwan National Park,Nepal

- Stopover behavior of Red-eyed Vireos (Vireo olivaceus) during fall migration on the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula

- Phylogeography and morphometric variation in the Cinnamon Hummingbird complex: Amazilia rutila (Aves: Trochilidae)

- Plastering mud around the entrance hole affects the estimation of threat levels from nest predators in Eurasian Nuthatches