Taxonomic status of grey-headed Yellow Wagtails breeding in western China

2022-01-07AlexanderHellquistFredrikFribergPetterHaldPeterSchmidtMingMaGouJunUrbanOlssonandPerAlstr

Alexander Hellquist , Fredrik Friberg, Petter Haldén, Peter Schmidt, Ming Ma, Gou Jun,Urban Olsson and Per Alström

Abstract

Keywords: Bioacoustics, Mitochondrial DNA, Morphology, Motacilla flava, Systematics, Undescribed populations

Background

The taxonomy of Yellow Wagtails (Motacilla flava

)sensu lato is notorious, as evident by longstanding discussions on the validity and relationships of the numerous subspecies [see Alström and Mild (2003)for a review], and the complex is often separated into two species, Western Yellow Wagtail (M. flava

) sensu stricto and Eastern Yellow Wagtail (M. tschutschensis

)(e.g., del Hoyo and Collar 2016; Gill et al. 2021). Despite an extensive literature on the subject, future discoveries and revisions are likely as birds in less known parts of the range are studied in more detail, and as more genetic data is published (see e.g. Ödeen and Alström 2001; Alström and Ödeen 2002; Voelker 2002; Ödeen and Björklund 2003; Pavlova et al. 2003; Drovetski et al.2018; Harris et al. 2018). Based on the discordance between mitochondrial and nuclear genetic data identified by Alström and Ödeen (2002), Drovetski et al.(2018) and Harris et al. (2018), and the overall slight nuclear genetic divergence, we chose in this paper to tentatively not adopt the split into two separate species but instead treat all discussed forms as Yellow WagtailMotacilla flava

.During a trip to the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China in May 2011, AH, FF, PH, PS and MM encountered Yellow Wagtails in several areas.

As expected based on distribution maps in e.g. Alström and Mild (2003),M. f. feldegg

(hereafterfeldegg

) were found breeding in westernmost Xinjiang along the Kazakh border, and phenotypes with white supercilia matchingM. f. zaissanensis

(hereafterzaissanensis

;treated as synonymous withM. f. tschutschensis

by Alström and Mild 2003 but better regarded as a separate subspecies or an intergrade, see Hellquist 2021)were found breeding in the Altai Mountains in the northeastern part of the region.In addition, many males with bluish-grey heads reminiscent of the subspeciesM. f. thunbergi, M. f.cinereocapilla, M. f. pygmaea

orM. f. macronyx

(hereafterthunbergi

,cinereocapilla

,pygmaea

andmacronyx

,respectively) were observed. Some of these, encountered at scattered locations in Dzungaria (i.e. Xinjiang north of the Tien Shan Mountains), behaved like migrants. However, at three sites, they appeared to be territorial (Fig. 1):

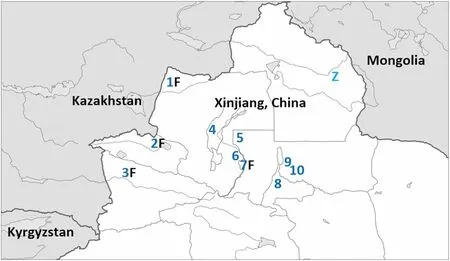

Fig. 1 Map of northern Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region,China and adjacent territories. Dark blue numbers mark localities mentioned in the text where grey-headed Yellow Wagtails appear to breed. 1 Jiyekexiang and Tarbagatagay. 2 Ebinur Lake. 3 Ili River Valley.4 Karamay. 5 Mosuowan Station for Desert Research. 6 Moguhu Reservoir. 7 Shihezi. 8 Urumqi. 9 Liuyunhu. 10 Fukang. Black “Fs”mark localities where M. f. feldegg phenotypes have been observed alongside grey-headed birds. The light blue “Z” marks Kalawu Tekele Lake in the Chinese Altai (47° 01ʹ N, 89° 45ʹ E), where M. f. zaissanensis phenotypes were observed breeding in 2011

• By freshwater ponds west of Ebinur Lake (45° 09ʹ N,82° 36ʹ E).

• Close to the Kazakh border north of the village of Jiyekexiang (46° 28ʹ N, 82° 48ʹ E).

• By a shallow lake west of the village of Liuyunhu (44°14ʹ N, 87° 53ʹ E).

Here, males with bluish-grey heads were singing from perches on wires and in tall grass or reeds. By Ebinur Lake, FF observed one bird carrying nest material. At both Ebinur Lake and Jiyekexiang, the birds were seen alongsidefeldegg

phenotypes breeding in the same habitats. Females associated with the males appeared similar tofeldegg

females. In this note, we will refer to this Yellow Wagtail population of unknown identity as “grey-headed”to denote the lack of white supercilium in most birds, and paler head in males compared to black-headedfeldegg

males.In May 2018, PA and UO together with Geoff J. Carey,Paul J. Leader and Jonathan Martinez visited Xinjiang,part of the time together with MM and GJ, and observed grey-headed birds that appeared to be breeding (singing,sometimes pairs giving alarm calls) at the following locations (Fig. 1):

• Mosuowan Station for Desert Research (45° 01ʹ N,86° 02ʹ E).

• Moguhu Reservoir (44° 28ʹ N, 85° 56ʹ E).

• In vicinity of Shihezi (44° 18ʹ N, 86° 04ʹ E).

• In vicinity of Fukang (44° 09ʹ N, 87° 59ʹ E).

• Close to the province capital Urumqi (43° 49ʹ N, 87°37ʹ E).

Field studies by MM and GJ during the summer months further confirm the presence of breeding grey-headed birds at many of these locations, as well as in the vicinity of Karamay (45° 34ʹ N, 84° 53ʹ E). This population has not been described in existing literature (e.g. Ma 2011). The purpose of this paper is to describe its approximate distribution, appearance and vocalisations, and to discuss its taxonomic identity as either an undescribed subspecies or an intergrade form.

Methods

Morphology and vocalisations

The descriptions below are based on the field studies conducted in 2011 and 2018, complemented by studies by MM and GJ in other years, as well as on a review of photos online, primarily on the Birds of Xinjiang, China webpage (http:// xinji ang. birds. watch/). In total, photos of 92 males and 14 females from Xinjiang in spring and summer (March–August) have been examined (photos and URLs for photos of these birds are found in Additional file 1: Figure S1–S67, Additional file 2: Table S1 and Additional file 3: Table S2).

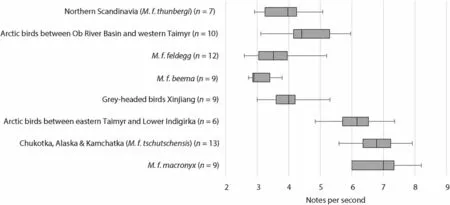

Descriptions of vocalisations are based on recordings made in 2011 and 2018. In total, the recordings contain songs from 16 different males and contact calls from 19 males and three females (URLs can be found in the Additional file 3: Table S3). These recordings were compared with recordings from other taxa (www. xeno- canto.org, www. hbw. com/ ibc, www. macau layli brary. org, own recordings), and differences in songs were quantified in the software packages Audacity 2.4.2 (Audacity Team)and Raven Lite 2.0 (Cornell Lab of Ornithology), by counting average number of notes per second in sonograms of different taxa.

While a majority of studied grey-headed males can be separated with reasonable certainty from other Yellow Wagtail taxa that occur or could potentially occur in Xinjiang based on a combination of plumage features and vocalisations, as described below, the studied females are very similar to femalefeldegg

. Asfeldegg

breeds in at least western Dzungaria in the same habitats as grey-headed birds, albeit seemingly in lower numbers, there is a small chance that our sampled females might include a fewfeldegg

.Genetic analysis

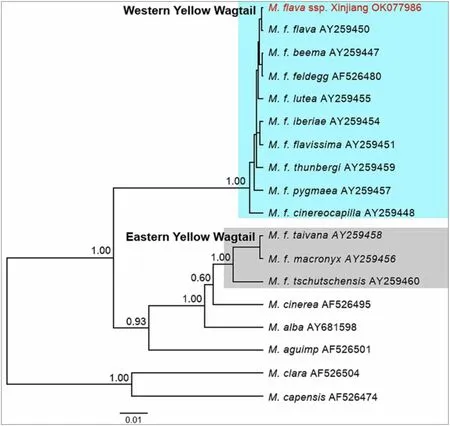

A DNA sample was taken from a freshly dead bird found at Linzhengzi, Fukang, Xinjiang on 12 May 2018 (Additional file 1: Figure S47), where the species appeared to be breeding at high density. Genomic DNA from muscle was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacterer’s protocol. The complete mitochondrial nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase subunit 2 (ND2) was amplified by PCR in a 12.5 μL reaction volume consisting of 10 μL VWR Red Taq DNA Polymerase Master Mix,0.5 μL of each primer [L5204, Cicero and Johnson (2001);H6313, Johnson and Sorenson (1998)], 1 μL deionised HO and 0.5 μL of DNA sample, in an Eppendorf autothermal cycler (AG Eppendorf). Cycling conditions were 2 min at 95 °C, 40 cycles of 40 s at 95 °C, 1 min at 50 °C,and 2 min at 72 °C, and a final extension of 6 min at 72 °C. PCR amplicons were then visualised on 1.0% agarose gels stained with GelRed, and purified by Exonuclease I + FastAP (Fermentas Life Sciences, Waltham, MA,USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Sequencing of the purified PCR products was performed by GATC Biotech AG (Cologne, Germany), using internal primers L5219 (Sorenson et al. 1999) and H5578(Cicero and Johnson 2001). This sequence has been deposited in GenBank (accession number OK077986).ND2 sequences of all otherMotacilla flava

taxa (sensu Alström and Mild 2003) were downloaded from GenBank(GenBank accession numbers in Fig. 7). Sequences were aligned in SeaView 5.0 (Guoy et al. 2010). The best-fit model for phylogenetic analysis was determined by the Bayesian Information Criterion in jModeltest2 (Darriba et al. 2012). Phylogenetic analysis of the ND2 matrix were run under the best-fit model (HKY + I), a Constant Population Size as well as Yule model (in different analyses),a strict molecular clock (with rate 1.0) and default priors in BEAST 1.10.4 (Drummond et al. 2012). Twenty million generations were run, with trees sampled every 10,000 trees. Convergence to the stationary distribution of the single chains was inspected in Tracer v. 1.7.1 (Rambaut et al. 2014) using a minimum threshold for the effective sample size (> 200). The joint likelihood and other parameter values reported large effective sample sizes (> 1000),and the trace plot had the shape of a “dense, straight,furry caterpillar”. Good mixing of the MCMC and reproducibility were established by multiple runs from independent starting points. The first 20% of the sampled trees were discarded as burn-in, well after stationarity had been reached, and the posterior probabilities were calculated from the remaining samples. Trees were summarized using TreeAnnotator v. 1.7 (in the BEAST package), choosing “Maximum clade credibility tree” and“Mean heights” and displayed in FigTree 1.4.4 (Rambaut 2018). Both jModeltest and BEAST were run on the CIPRES portal (Miller et al. 2010).Results

Distribution

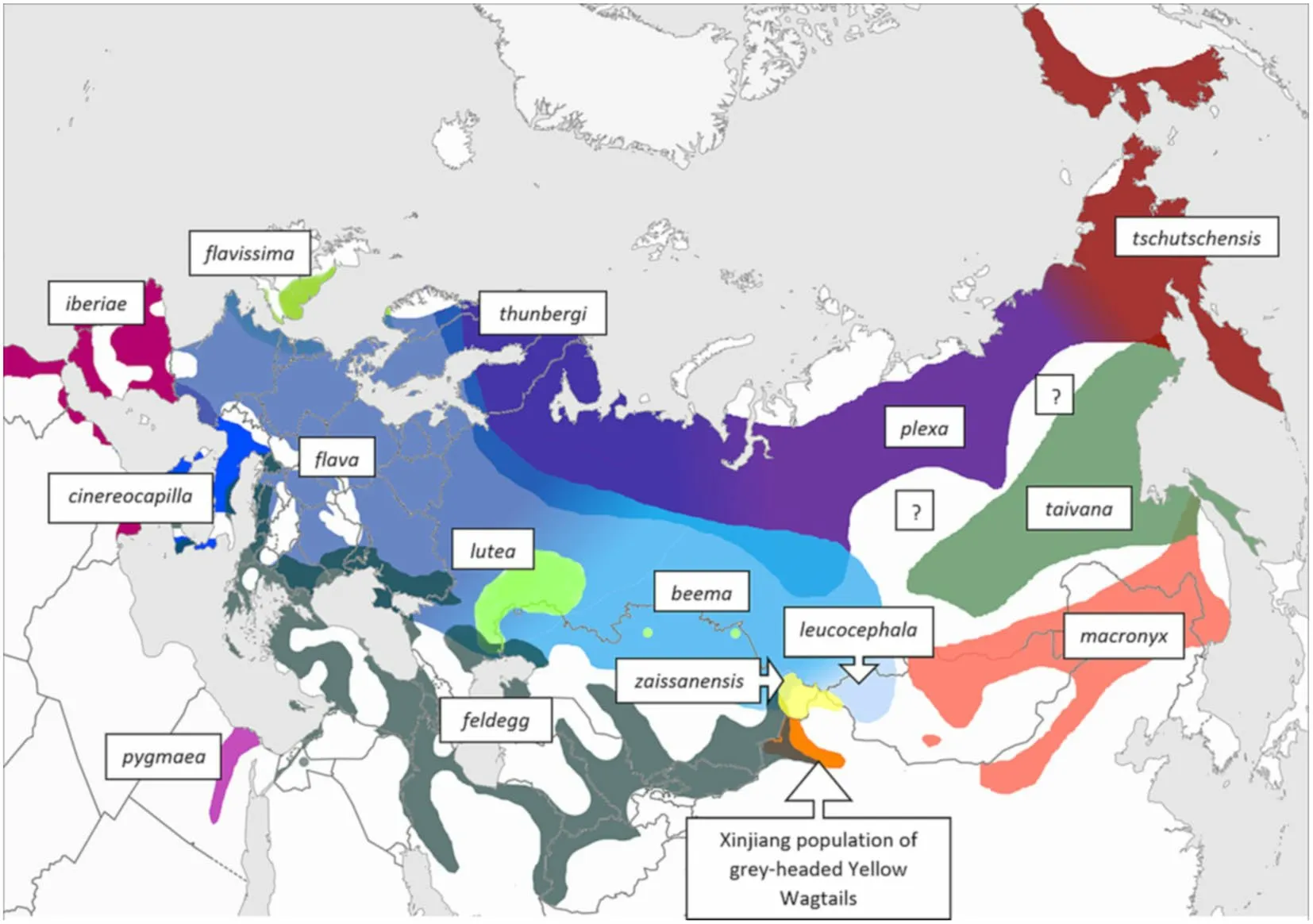

Based on our field studies and the reviewed online photos, we assert that the Xinjiang population of greyheaded Yellow Wagtails are summer visitors (arriving in spring from late March) primarily to the belt of cultivated land running from the Urumqi area westwards along the northern slopes of the Tien Shan range and in cultivated areas around Jiyekexiang and Tarbagatay. This pattern is not unexpected given that most of Dzungaria is characterized by an arid climate and saline land. We have also found online photos (http:// xinji ang. birds. watch/ photos/ 0034/ 001/ 00340 043301. jpg and http:// xinji ang. birds.watch/ photos/ 0034/ 001/ 00340 043601. jpg) of two greyheaded birds taken in the Altai City area in the northernmost part of Xinjiang, from where there are also photos ofzaissanensis

phenotypes with prominent white supercilia. We have found no photos of Yellow Wagtails taken in the arid central parts of the Dzungarian Basin or in Xinjiang south of the Tien Shan range, although presumably, they can occur there during migration. We have found photos (https:// birds. kz/ v2pho to. php?l= en&s=03930 2123) of grey-headed males that closely match the appearance of those breeding in Xinjiang taken in the vicinity of Taldykorgan in eastern Kazakhstan in early April, possibly indicating a westerly migration route and/or breeding in this area as well. See Fig. 2 for the approximate breeding distribution of grey-headed birds in relation to ranges of the other Yellow Wagtail subspecies recognized by Gill et al. (2021) [following Alström and Mild (2003), with the addition ofplexa

based on Harris et al. (2018)], as well aszaissanensis

(following Hellquist 2021).

Fig. 2 Approximate breeding ranges of Yellow Wagtail subspecies currently recognized by Gill et al. (2021), as well as those of the disputed form zaissanensis and the population of grey-headed Yellow Wagtails dealt with in this paper. The map draws primarily on distributions given in Alström and Mild (2003), Red’kin et al. (2016), Ferlini (2016), Svensson and Shirihai (2018), Ferlini (2020), Ferlini (2021), Hellquist (2021), and on information provided by Yang Liu, Gombobaatar Sundev and Terry Townshend (in litt.). In many cases, detailed distributions as well as relationships between taxa in areas of contact are still poorly known

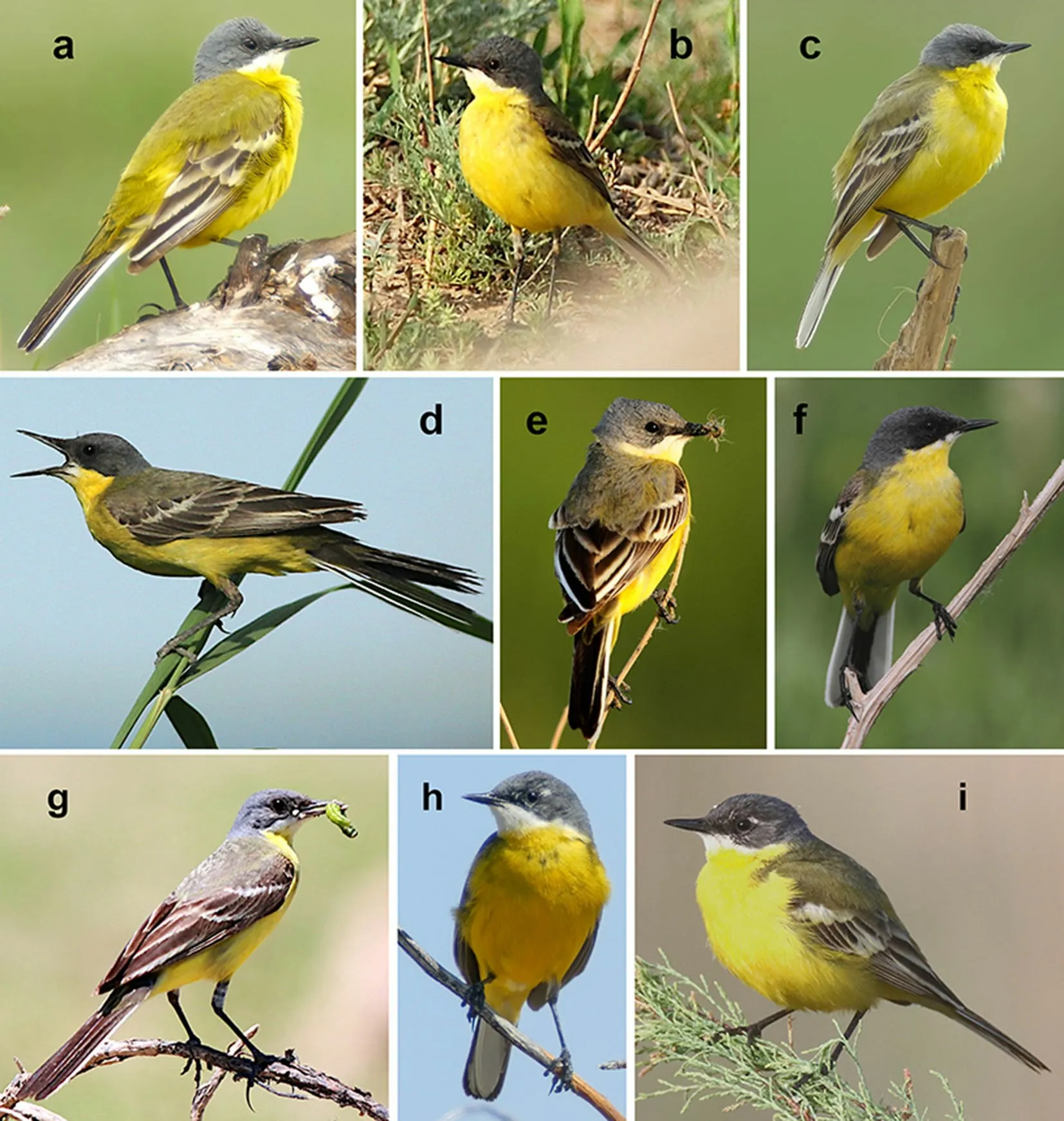

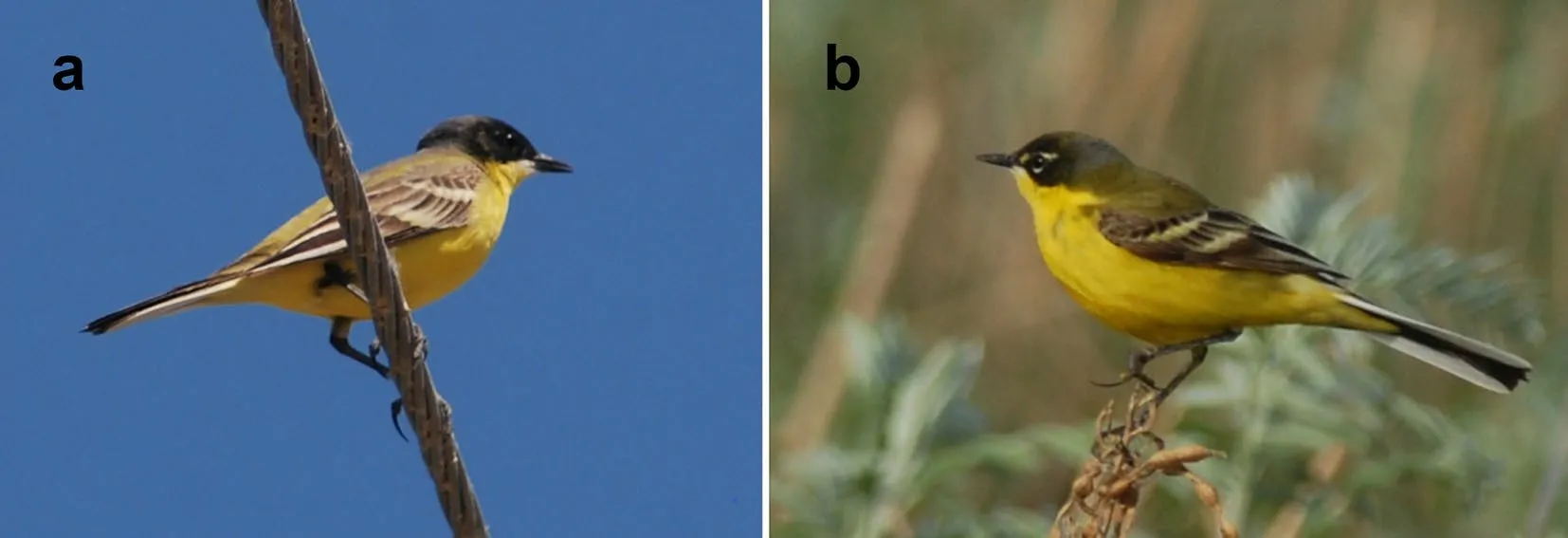

Male plumage

Figure 3 shows examples of grey-headed males. As in other Yellow Wagtail populations, the head pattern is somewhat variable. In the studied photos (n

= 92), 75% of the males lack white supercilium entirely. Many of these show a uniform blue-grey hood, without the contrast between darker ear-coverts and paler crown that is usually, but not always, present inthunbergi

(Alström and Mild 2003). Other males are similar to typicalthunbergi

in this regard. 14% of the studied males show very short white supercilia, in most cases only a few feathers in front of or/and behind the eye [as is the case also in manythunbergi

; Alström and Mild (2003), Hellquist (2021)].The remaining 11% show longer supercilia extending both in front of and behind the eye, but still markedly thinner and shorter than in e.g. typicalM. f. flava

andM.f. beema

(hereafterflava

andbeema

, respectively), or in mostzaissanensis

phenotypes breeding in the Altai.Eighty-one percent of the studied males show clean yellow breasts without dark spotting. In this regard, they are similar to southern Yellow Wagtail subspecies, includingcinereocapilla

,feldegg

,beema

andmacronyx

(Alström and Mild 2003). By comparison, a majority of Europeanthunbergi

and dark-headed birds breeding in the Siberian Arctic show dark markings on the breast [Alström and Mild (2003), Hellquist (2021); the taxonomic position of Siberian dark-headed birds is disputed; they are synonymised withthunbergi

by Alström and Mild (2003)but separated asM. f.

“plexa

”—hereafterplexa

—by e.g.Harris et al. (2018); see also Pavlova et al. (2003); Red’kin et al. (2016); Drovetski et al. (2018); Hellquist (2021)].Eighteen percent of the studied males show a few dark spots on the upper breast, while only one male in the sample (1.3%) shows extensive spotting like many Europeanthunbergi

and Siberian dark-headed birds.

Fig. 3 Variation in male plumage in grey-headed Yellow Wagtails breeding in Xinjiang. Note bluish grey crown and lack of supercilium in a–g, and clean yellow breast and extensive white on throat in most birds. g depicts a breeding bird carrying food to nestlings, while the bird in e carries nest material. h–i illustrate the minority of males in the studied sample that show short supercilia, approaching appearance of some M. f. zaissanensis,cf. Figure 9b. a Mogohu Lake, 15 May 2018 (Per Alström). b Jiyekexiang, 16 May 2011 (Petter Haldén). c Moguhu Lake, 15 May 2018 (Per Alström) d Fukang, 29 June 2019 (Ming Ma). e Shihezi, 10 May 2010 (Jie Xu). f Shihezi, 10 May 2010 (Jie Xu). g Fukang, 22 June 2016 (Ming Ma). h Urumqi 11 May 2018 (Per Alström). i Fukang, 12 May 2018 (Jonathan Martinez)

On average, the grey-headed males show considerably more white on the throat than typicalthunbergi

,beema

,feldegg

andmacronyx

, i.e. they are more similar tocinereocapilla

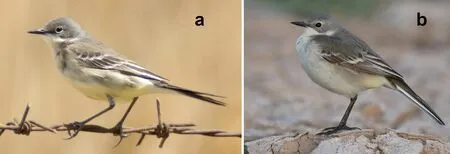

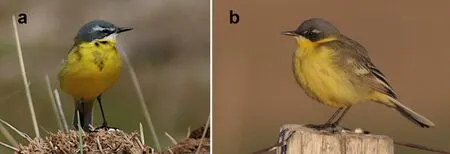

in this regard (cf. Alström and Mild 2003).In 39%, more than half of the throat is white; 59% show conspicuous white below the bill covering less than half of the throat, while only two individuals in the sample(2.2%) show entirely yellow throat (at most a few white feathers at bill base).Female plumage

Studied females are very similar to femalefeldegg

, with rather pale greyish upperparts and mostly white underparts with reduced amounts of yellow, poorly defined dark loral stripe, weak or no supercilium and in several birds a nearly unbroken white eye-ring (two examples in Fig. 4). Three of the 14 females in the sample show more extensive yellow, covering most of the underparts, just as in somefeldegg

females (Alström and Mild 2003), but the colour is still pale and the upper breast and throat are whitish.

Fig. 4 Females photographed in proximity to grey-headed males. Note greyish appearance with limited supercilium, very similar to M. f. feldegg females. a Urumqi, 11 May 2018 (Per Alström). b Fukang, 22 May 2018 (Jonathan Martinez)

Fig. 5 Vocalisations in grey-headed birds. Dots […] between sonograms denote that time between notes or phrases is compressed. a three single song notes from a male (depicted in Additional file 1: Figure S15), Ebinur Lake, 14 May 2011 (XC616907) (Alexander Hellquist); b two single song notes given by a different male, Ebinur Lake, 14 May 2011 (XC616910) (Alexander Hellquist); c song from the same male giving four-, three- and single-note phrases, Moguhu Lake, 15 May 2018 (XC616923) (Per Alström); d song from male (depicted in Additional file 1: Figure S23) giving three-,two- and single-note phrases, Liuyunhu, 20 May 2011 (XC616918) (Alexander Hellquist); e one call followed by twittering song in male, Urumqi,11 May 2018 (XC616927) (Per Alström); f one call from female, Ebinur Lake, 14 May 2011 (XC616914) (Alexander Hellquist); g three calls from male(depicted in Additional file 1: Figure S15), Ebinur Lake, 14 May 2011 (XC616907). Note saw-tooth pattern at end of descending part of call, producing a rasping quality (Alexander Hellquist); h: one call from male (depicted in Additional file 1: Figure S16), Ebinur Lake, 14 May 2011 (XC616913)(Alexander Hellquist); i one call from male, Moguhu Lake, 15 May 2018 (XC616922) (Per Alström); j–k two calls from male, Urumqi, 11 May 2018(XC616924). k is soft without r-sound, like typical calls in e.g. European M. f. thunbergi (Per Alström); l one call from a different male, Urumqi, 11 May 2018 (XC616926) (Per Alström)

Song

The 13 singing males that were recorded all gave single rasping song notes, similar to typical songs in western Yellow Wagtail subspecies, e.g.flava

,feldegg

,beema

,cinereocapilla

and Europeanthunbergi

[Fig. 5a–b; cf.sonograms in Alström and Mild (2003) and Hellquist(2021)]. Nine of the males also gave song phrases consisting of 2–4 repeated notes (Fig. 5c–d). The pace of this “fast song type” is similar to that of western Yellow Wagtail subspecies [see sonograms in Alström and Mild (2003)], being slower than in populations breeding in eastern Arctic Siberia (M. f. tschutschensis

; hereaftertschutschensis

) and inmacronyx

(Fig. 6) (Hellquist 2021).In one bird, a fast twittering song type was recorded along with single rasping notes (Fig. 5e). Several males also gave series of chirping notes and notes reminiscent of contact calls that might function either as alarm calls or a (relaxed) song. Such series can be heard also in other Yellow Wagtail populations.Calls

The recorded contact calls are reminiscent of those of northwestern Yellow Wagtail subspecies, e.g.flava

,thunbergi

andbeema

[see sonograms in Alström and Mild(2003)]. In most cases, there is a discernable r-sound at the very end of the call, giving it a slightly rasping quality following the soft onset. In sonograms (Fig. 5f‒j, l),this is visible as a saw-tooth pattern at the end of the descending part of the call. In this respect, the calls are similar to some calls ofbeema

andfeldegg

, although typicalfeldegg

calls are even more rasping [see sonograms in Alström and Mild (2003)]. A few calls from the Xinjiang birds lack the r-sound entirely, as typical calls in Europeanthunbergi

(Fig. 5k). All calls are less sharp than the Citrine WagtailMotacilla citreola

-like typical calls given by Arctic grey-headed birds east from Taimyr (plexa

; see Hellquist 2021) and by the eastern taxatschutschensis

,M.f. taivana

andmacronyx

(Alström and Mild 2003).DNA

A total of 1041 bp were obtained for the mitochondrial ND2 gene. The ND2 tree shows the single sample from Xinjiang to be nested in the clade of western taxa, with posterior probability 1.00 (Fig. 7).

Discussion

Males of grey-headed Yellow Wagtails breeding in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China are closely similar in plumage to the widely disjunctcinereocapilla, pygmaea, thunbergi

,plexa

andmacronyx

, whereas females resemble females of the marginally sympatricfeldegg

(Fig. 4). The songs agree with those of westernM. flava

taxa but differ from easternM. flava

taxa, whereas the calls are rather similar to those of northwesternM. flava

taxa, but not to the typical calls of southwestern (includingfeldegg

andcinereocapilla

) and eastern (includingplexa

andmacronyx

) ones (Alström and Mild 2003;Hellquist 2021). Mitochondrial DNA places the single sequenced Xinjiang bird in the western clade. Two possibilities may be considered regarding the taxonomic status of the Xinjiang population of grey-headed birds:

Fig. 6 Box plot showing notes per second in “fast song type” phrases in Yellow Wagtails of different taxa/geographic regions. For recordings containing multiple phrases from one individual, pace is calculated as average of three song phrases. As evident, the pace of the song in grey-headed birds in Xinjiang aligns with that of Scandinavian M. f. thunbergi as well as with M. f. feldegg and M. f. beema, being slower than in birds in the Siberian Arctic and in M. f. macronyx (cf. Hellquist 2021)

Fig. 7 Mitochondrial ND2 tree including all taxa in the Motacilla flava complex sensu Alström & Mild (2003), with the Xinjiang sample highlighted in red in the Western Yellow Wagtail clade. Note that the mitochondrial tree does not represent the true species phylogeny of Motacilla (cf. Harris et al. 2018)

1. They are the result of interbreeding between adjacent taxa.

2. They deserve recognition as a separate, as yet undescribed, subspecies.

Regarding the first possibility, taxa breeding in proximity to the grey-headed birds, thus constituting potential sources of intergradation, arefeldegg

,beema

andzaissanensis

, with at leastfeldegg

even occurring in sympatry with grey-headed birds in some locations in western Dzungaria at least east to Shihezi (observations by PA and GJ). The taxonbeema

breeds in eastern Kazakstan and southern Siberia (Alström and Mild 2003) whilezaissanensis

breeds in the Altai Mountains of China, Kazakstan and possibly Russia and Mongolia (Hellquist 2021).Although the grey-headed males are clearly different fromfeldegg

,beema

andzaissanensis

, they have some features in common with these, including clean yellow breasts, and contact calls that are similar to those ofbeema

andzaissanensis

as well as many softer calls offeldegg

(cf. Alström and Mild 2003; Hellquist 2021). They show more white on the throat than typicalbeema

andfeldegg

, although somebeema

andfeldegg

also show quite extensive white throats [more commonly in the eastern part of the range offeldegg

; Alström and Mild (2003)].According to Alström and Mild (2003), some intergrades betweenfeldegg

andflava

are similar tocinereocapilla

,which in turn is similar to the Xinjiang birds. Presumably,the same can be true for intergrades betweenfeldegg

andbeema,

considering the great similarity betweenbeema

andflava

. A few odd phenotypes were observed in the same localities as territorial grey-headed birds in 2011,including one “pseudo-feldegg

” showing mostly black heads but greyish napes (Fig. 8a) and one “superciliaris

”with a largely blackish head with a whitish supercilium(Fig. 8b) (these are not included in the analysis of male plumage above). These birds indicate thatfeldegg

at the eastern limit of its range might be subject to introgression from the population of grey-headed birds, frombeema

or fromzaissanensis

. Ferlini (2016) demonstrates howfeldegg

has expanded in Central Asia over the last centuries as deserts have been turned into arable land,which might increase potential for interbreeding with other taxa, even though he finds no evidence for changes in the distribution at the very eastern edge of the range,i.e. western Xinjiang, from the late nineteenth century and onwards. The small proportion of grey-headed birds in the studied material showing a thin supercilium could be a sign of influence frombeema

orzaissanensis

,while, conversely, one male among the breedingzaissanensis

studied in the Chinese Altai in 2011 showing a weak supercilium could indicate introgression from greyheaded birds (Fig. 9b). Further research in these areas would be of interest, as well as in adjacent parts in e.g.easternmost Kazakhstan where it seems likely that greyheaded birds also occur.

Fig. 8 Examples of odd male M. flava phenotypes observed in westernmost Xinjiang in 2011. The bird in a shows a plumage consistent with M.f. feldegg, save for a greyish nape that might indicate introgression with grey-headed populations. The bird in b shows a similar plumage but also white supercilium (matching form “superciliaris”). a Ebinur Lake, 14 May 2011 (Alexander Hellquist). b Jiyekexiang, 15 May 2011 (Petter Haldén)

Fig. 9 M. f. zaissanensis males. The bird in a has a typical plumage shown by most studied males in this population, while the bird in b has a rather poorly developed white supercilium. a Kalawu Tekele Lake, 19 May 2011 (Alexander Hellquist). b Kalawu Tekele Lake, 19 May 2011 (Peter Schmidt)

In support of the hypothesis that the grey-headed birds constitute an undescribed subspecies, the majority of the males show a distinct and consistent head pattern,which does not match that of any other taxon breeding nearby. The variability in the plumage seems comparable to that of other Yellow Wagtail subspecies. Moreover, grey-headed birds appear to have a discrete breeding area where other breeding phenotypes are rare or absent,save for the westernmost part wherefeldegg

also occurs.It could also be argued that the geographic position of the breeding area is somewhat odd if grey-headed birds would constitute intergrades between two or more taxa.While some localities, e.g. around Tarbagatay, lie in between the ranges offeldegg

andzaissanensis

, no Yellow Wagtails are known to breed directly east of the breeding sites of grey-headed birds around Urumqi. These sites are thus not located in between known distributions of other Yellow Wagtails, making the intergradation hypothesis seem less likely. However, the ranges of these taxa have surely shifted over time as a result of, e.g., glacial periods, so it is possible that past distributions were more in agreement with expectations from an introgression scenario.Looking farther east, there are two Yellow Wagtail taxa breeding at roughly the same latitudes as the grey-headed birds in Xinjiang:M. f. leucocephala

(hereafterleucocephala

) andmacronyx

(Fig. 2). According to the literature (e.g. Alström and Mild 2003),leucocephala

breeds in northwestern Mongolia and adjacent parts of Russia.Based on current knowledge, the ranges ofleucocephala

and the grey-headed birds in Xinjiang are thus not adjacent but separated by the range ofzaissanensis

. The taxonmacronyx

breeds in Mongolia, northeastern China and the Russian Amur region. It is overall very similar to the grey-headed Xinjiang birds, but it shows on average less white on the throat in males, and has different song and call, and a more male-like female plumage (Alström and Mild 2003; Hellquist 2021). Moreover, the mitochondrial ND2 sequence from the sampled grey-headed Xinjiang bird supports that it belongs in the western group of Yellow Wagtails and not in the eastern group wheremacronyx

belongs (cf. Ödeen and Alström 2001; Alström and Ödeen 2002; Voelker 2002; Ödeen and Björklund 2003;Pavlova et al. 2003; Drovetski et al. 2018; Harris et al.2018).Conclusions

To conclude, in our opinion, the grey-headed birds breeding in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China most likely represent an undescribed Yellow Wagtail subspecies. However, more research is needed to firmly establish their relationships with other populations and to gain a better understanding of their distribution and biology.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at https:// doi.org/ 10. 1186/ s40657- 021- 00289-y.

Additional file 1: Figure S1–S67. Photos of 67 grey-headed Yellow Wagtails taken in Xinjiang and included in the analysis of plumage.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Data on photos in Figure S1–S67.

Additional file 3: Table S2. URLs for photos of 39 grey-headed Yellow Wagtails in Xinjiang published online and included in the analysis of plumage. Table S3. URLs for recordings of 25 grey-headed Yellow Wagtails in Xinjiang published online and included in the analysis of vocalisations.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Meng Chao, Lianfu Gu, Jonathan Martinez, Wen Ming, Bo Ning, Jian Peng, Congda Wang, Yong Xia, Jie Xu, Bo Zhao and Yuehui Zhao for allowing us to use their photos, and to Yang Liu, Gombobaatar Sundev and Terry Townshend for providing information about the distribution of discussed forms.

Authors’ contributions

All authors took part in the field work. AH conducted the analysis of morphology and vocalizations. UO and PA conducted the genetic analysis. AH drafted the manuscript and all other authors helped to revise it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

PA gratefully acknowledges support from Jornvall Foundation and the Swedish Research Council (grant No. 2015-04402).

Availability of data and materials

Photos and URLs for photos and URLs for sound recordings of birds included in the analyses of plumage and vocalisations are available in additional files.Other data used in the study are available from one of the corresponding authors (AH) on request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author details

Fatburs kvarngata 17, 118 64 Stockholm, Sweden.Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 818 Beijing Road, Urumqi 830011, Xinjiang, China.Xinjiang Birdwatching Society, 311 Nongda East Road, Urumqi 830091, Xinjiang, China.Systematics and Biodiversity, Department of Biology and Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Göteborg, Sweden.Gothenburg Global Biodiversity Centre,Gothenburg, Sweden.Animal Ecology, Department of Ecology and Genetics, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Norbyvägen 18D, 752 36 Uppsala, Sweden.Key Laboratory of Zoological Systematics and Evolution,Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China.Edeby 9, 741 91 Knivsta, Sweden.Lenabergsvägen 33, 743 92 Vattholma,Sweden.Tallmovägen 9, 756 45 Uppsala, Sweden.

Received: 16 May 2021 Accepted: 18 October 2021

杂志排行

Avian Research的其它文章

- Taxonomic revision of the Savanna Nightjar (Caprimulgus affinis) complex based on vocalizations reveals three species

- The composition of mixed-species flocks of birds in and around Chitwan National Park,Nepal

- True grit: ingestion of small stone particles by hummingbirds in West Mexico

- Stopover behavior of Red-eyed Vireos (Vireo olivaceus) during fall migration on the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula

- Phylogeography and morphometric variation in the Cinnamon Hummingbird complex: Amazilia rutila (Aves: Trochilidae)

- Plastering mud around the entrance hole affects the estimation of threat levels from nest predators in Eurasian Nuthatches