凡纳滨对虾“眼柄-促雄性腺-精巢”内分泌轴调控精巢发育的分子机制研究

2021-12-09陈康轩李诗豪李富花

陈康轩, 李诗豪, 李富花

凡纳滨对虾“眼柄-促雄性腺-精巢”内分泌轴调控精巢发育的分子机制研究

陈康轩1, 2, 李诗豪1, 李富花1

(1. 中国科学院海洋研究所 实验海洋生物学重点实验室, 山东 青岛 266071; 2. 中国科学院大学 北京 100049)

位于甲壳动物眼柄的神经内分泌器官在调控甲壳动物的繁殖过程中发挥着重要作用。已有证据表明“眼柄-促雄性腺-精巢”内分泌轴调控十足目雄性甲壳动物精巢的发育, 但是该过程的分子机制仍不清楚。本研究以凡纳滨对虾()为实验对象, 研究了切除雄性对虾的单侧眼柄对促雄性腺内胰岛素样促雄性腺素基因()和精巢内基因表达的影响。结果表明, 切除单侧眼柄后,基因的表达明显上调; 比较了眼柄切除前后对虾精巢的转录组数据, 共有267个基因的表达量出现明显变化。对精巢内差异表达基因进行功能分析发现, 多个参与性腺发育和内分泌调控的基因发生表达上调, 如()、保幼激素环氧水解酶(juvenile hormone epoxide hydrolase,)、细胞色素P450酶系基因以及泛素化系统相关基因等。对差异表达基因进行荧光定量PCR验证, 结果与转录组结果一致, 证实了转录组结果的可靠性。研究结果表明, 对虾眼柄调控精巢的发育很可能是通过影响促雄性腺中的表达, 进而调控精巢内、、内分泌及泛素化系统相关基因的表达实现的。研究结果对深入理解甲壳动物精巢发育的分子调控机制提供了重要依据, 对甲壳动物的人工繁育也具有重要指导意义。

对虾; 眼柄; 胰岛素样促雄性腺素; 精巢发育

十足目甲壳动物眼柄内的X器官/窦腺复合体(X-organ/sinus-gland complex, XO-SG)是其神经内分泌系统的中枢, 在调节动物新陈代谢、蜕皮、生殖发育等生理过程发挥着重要作用[1, 2]。通过人工摘除眼柄, 可以起到促进蜕皮、性腺成熟及生长的作用[3-7]。XO-SG复合体合成分泌的蜕皮抑制激素(Molt-inhibiting hormone, MIH)、甲壳动物雌性性激素(Crustacean female sex hormone, CFSH)、性腺抑制激素(Gonad inhibiting hormone, GIH)、甲壳动物高血糖激素(Crustacean hyperglycemic hormone, CHHs)等一系列神经肽激素在这些生理过程的调控中发挥着重要作用[8-13]。促雄性腺(androgenic gland, AG)是雄性甲壳动物所特有的, 其通过分泌胰岛素样促雄性腺素(Insulin-like androgenic gland hormone, IAG)参与甲壳动物雄性性别分化过程。雄性甲壳动物眼柄中的XO-SG复合体可以抑制促雄性腺的发育和基因的表达, 其中已经证实CHH家族等眼柄神经肽类激素直接负调控基因的表达[9, 14-17]。研究表明, 雄性甲壳动物的性别发育过程受到“眼柄-促雄性腺-精巢”内分泌轴的调控[14]。然而, 精巢中哪些基因受到“眼柄-促雄性腺-精巢”内分泌轴的调控参与雄性性别发育目前仍不十分清楚。转录组技术的发展和应用实现了对特定器官在特定条件下基因表达水平的高通量分析, 一系列性别发育相关基因也得到鉴定, 使得构建甲壳动物性腺发育的分子调节网络成为可能。本研究以凡纳滨对虾为实验对象, 研究了雄性对虾的单侧眼柄切除对促雄性腺内基因及精巢内基因表达的影响, 发现对虾基因及精巢内多个参与性腺发育和内分泌调控的基因发生明显上调表达。研究结果为深入理解甲壳动物精巢发育的分子调控机制提供了重要依据, 对甲壳动物的人工繁育也具有重要指导意义。

1 材料与方法

1.1 实验材料

健康的雄性凡纳滨对虾()来自于青岛市附近的养殖场(体长12 cm±0.2 cm, 体质量10.5 g±1.5 g)。

1.2 方法

1.2.1 眼柄切除

将60 尾健康的雄性凡纳滨对虾分为两组, 一组使用酒精喷灯烧红的镊子从基部烫断右侧眼柄, 另外一组作为对照组, 正常饲养。在(25±1) ℃曝气海水中饲养一周后, 取促雄性腺组织和精巢组织于液氮中速冻, –80 ℃冰箱保存。

1.2.2 总RNA提取及cDNA合成

使用Takara公司的RNAisol方法提取AG及精巢组织的总RNA。使用Nanodrop 2000检测样品浓度与纯度, RNA质量检测使用1.5%的琼脂糖凝胶电泳方法。使用Thermo公司的Revert Aid Fist Strand cDNA synthesis Kit进行AG和精巢组织cDNA第一链的合成。

1.2.3基因表达水平检测及转录组样品制备

使用荧光定量PCR分别对眼柄切除组和对照组每只对虾AG组织的基因表达水平进行检测。测定后, 根据基因表达水平, 选取实验组中该基因表达水平提高幅度较大的9个个体的精巢RNA样品用于转录组测序, 另外从对照组中选择该基因表达水平变化不大的9个体的精巢RNA样品用于转录组测序。为避免蜕皮时期对基因表达的影响, 所取样对虾均处于蜕皮间期。每组选择的9个精巢RNA样品每3个混合成一个样品, 每组包含3个生物学重复样品。实验组3个样品分别命名为EAT1、EAT2和EAT3, 对照组3个样品分别命名为ECT1、ECT2和ECT3。

1.2.4 转录组测序

RNA样品送至广州基迪奥生物科技公司测序, 首先使用带 Oligo (dT) 的磁珠富集真核生物mRNA, 超声片段化后作为模板进行cDNA双链合成。纯化后的双链cDNA经过末端修复与添加poly(A)尾后与测序接头连接。用AMPure XP beads筛选200 bp左右的cDNA, 进行PCR扩增, 最后使用AMPure XP beads纯化PCR产物, 获得测序文库。利用琼脂糖凝胶电泳、Qubit2.0 Fluorometer以及Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer等方法检测样品纯度、浓度与完整性后, 符合标准的文库使用Illumina HiseqTM 2500测序仪进行双末端测序。

1.2.5 测序数据比对

使用短reads比对工具Bowtie2(version 2.2.8)剔除核糖体RNA(rRNA)序列获得clean reads。利用凡纳滨对虾参考基因组(PRJNA438564)为索引, 使用HISAT2.2.4将双端测序的clean reads在参考基因组上进行比对。

1.2.6 生物信息分析

转录组数据分析参照基迪奥公司有参转录组分析的基本流程, 包括数据质控、序列比对分析、基因分析、 基因表达量统计、样本关系分析、组间差异分析、基因功能富集等。差异表达基因的筛选标准为: 差异倍数>2和错误发现率≤0.01。

通过从相应的InterProScan或Pfam结果中基因本体注释并进行富集分析。使用KEGG自动注释服务器将差异表达基因信息与KEGG数据库进行比对, 对涉及的基因通路进行注释。

1.2.7 实时荧光定量PCR

对筛选到的精巢差异表达基因, 使用Primer3.0 plus设计特异性引物(表1), 使用实时荧光定量PCR验证基因表达情况。以眼柄切除前后的精巢RNA反转录的cDNA为模板, 使用18S rRNA作为内参基因, 扩增条件为: 95 ℃预变性4 min; 95 ℃变性15 s, 56 ℃退火 20 s, 72 ℃延伸30 s, 扩增40个循环。使用2–ΔΔCT法计算基因的相对表达量, 对数据采用单因素方差分析[18]进行统计学检验, 以< 0.05和<0.01作为显著性差异和极显著差异的评价标准。

2 结果

2.1 眼柄切除对LvIAG基因表达的影响

通过real-time PCR 法检测, 眼柄切除组中基因在促雄腺组织中的相对表达量与对照组相比上调约12.2倍(图1), 表明眼柄切除后引起了基因的表达显著上调。

表1 引物的序列信息及退火温度

图1 眼柄切除处理组与对照组LvIAG基因在促雄腺中的表达水平检测

**. 差异极显著(<0.01)

**. very significant difference(<0.01)

2.2 转录组数据分析及差异表达基因鉴定

转录组测序共得到原始测序序列总计230 724 552条, 经过质量控制后获得高质量序列共226 147 040条, 占总测序数据的98.01%, 测序信息统计见表2。获得的测序数据与参考基因组比对率为83.05%~85.39%, 过滤后Q20范围为97.74%~ 98.18%, Q30在93.62%~94.44%。以上数据说明转录组测序的总体质量较好, 可用于后续的差异基因表达分析。

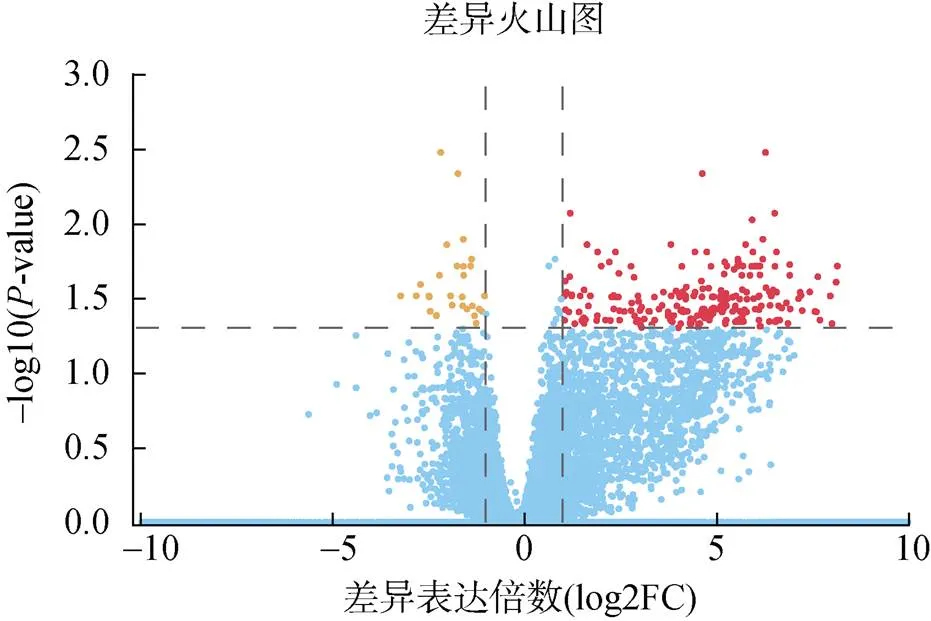

通过本次精巢差异转录组测序, 共获得267个差异表达基因, 其中有238个基因呈现上调表达, 29个基因呈现下调表达(图2)。

2.3 差异表达基因的富集分析

KEGG通路富集分析结果显示, 眼柄切除的对虾精巢转录组中差异表达基因主要富集在特定的代谢途径, 包括转运与分解代谢(Transport and catabolism)、碳水化合物代谢(carbohydrate metabolism)、信号分子与互作(signaling molecules and interaction)等(图3)。

表2 实验组和对照组精巢的转录组测序数据信息

图2 实验组和对照组精巢差异表达基因的火山图

注: 红色点: 表达上调基因; 黄色点: 表达下调基因; 蓝色点: 表达差异不显著基因

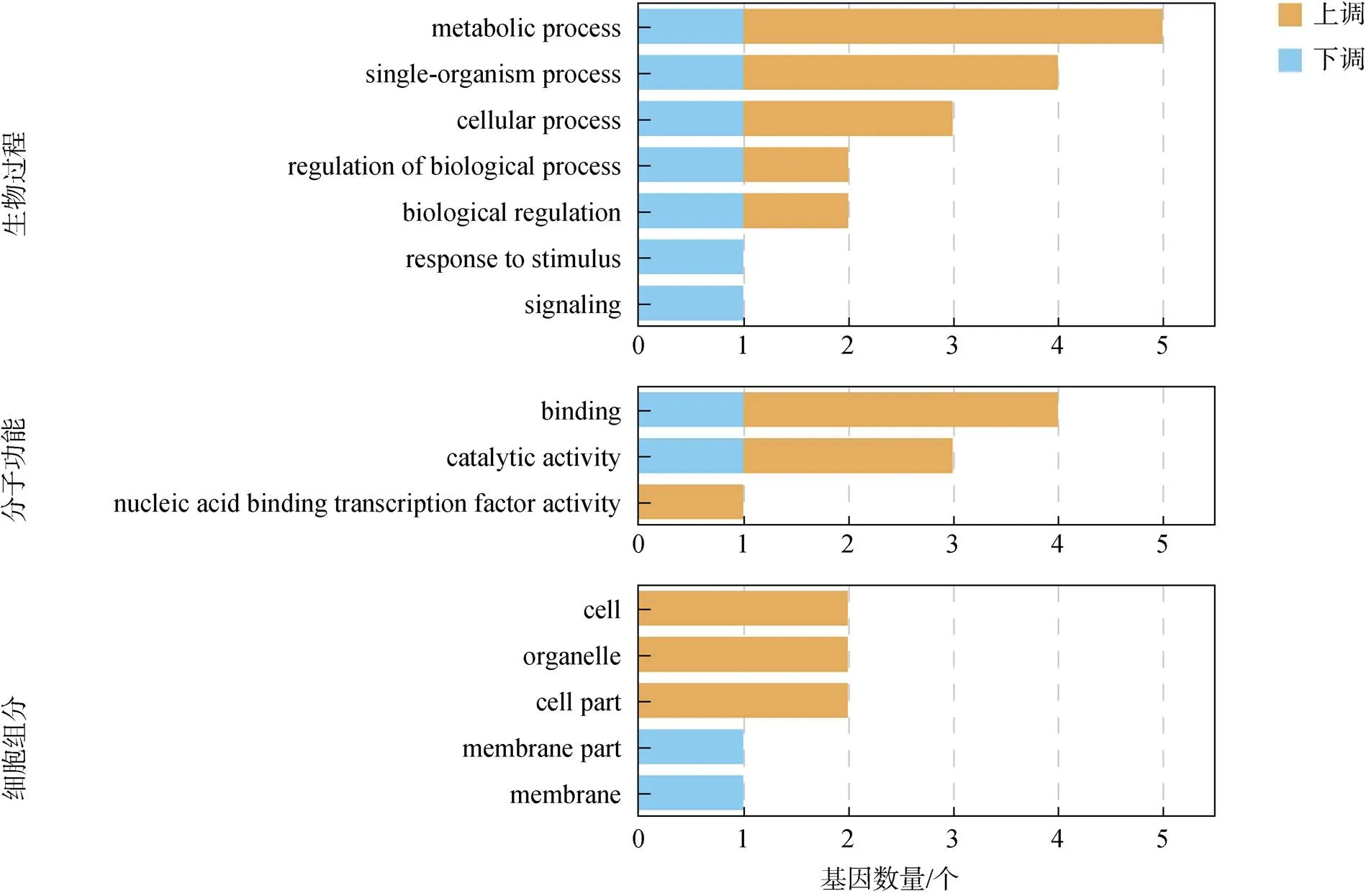

使用GO数据库, 将眼柄切除实验组中鉴定的精巢差异表达基因按照生物学过程、细胞组分和分子功能分别进行统计分析, 共富集到3个大类的15个过程中, 结果如图4所示。生物过程大类富集最多, 包括代谢过程(metabolism process)、单一生物过程(single- organism process) 以及细胞学过程(cellular process)。细胞组分大类中, 具有结合(binding)和催化活性(catalytic activity)的基因富集较多。

图3 实验组和对照组对虾精巢差异表达基因KEGG通路富集结果

注: EAT为眼柄切除实验组; ECT为对照组

图4 对虾精巢差异表达基因GO富集分析

注: 黄色部分: 实验组相对对照组表达上调基因; 蓝色部分: 实验组相对对照组表达下调基因

2.4 差异表达基因的功能分类与定量验证

根据已报道基因的功能, 将眼柄切除前后精巢中差异表达基因进行分类, 鉴定了一系列与性别发育、内分泌系统和泛素化系统等相关的基因(表3)。性别发育相关的基因表达量显著上调。内分泌系统相关的差异表达基因均呈现上调表达, 包括可能参与MF降解的保幼激素酯酶基因和细胞色素P450酶系基因和。泛素化系统相关基因包括泛素激活酶E1(ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1)、泛素偶联酶E2(ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2)和泛素特异性肽酶USP21(ubiquitin specific peptidase 21)均呈现上调表达趋势, 而E3泛素连接酶SH3RF1(E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase SH3RF1)则呈现下调表达。

表3 对虾精巢差异表达基因功能分类

为了验证转录组中所鉴定差异表达基因的可靠性, 选取了5个差异表达基因、、、、进行RT-qPCR验证。结果如图5所示, 每个基因的转录组数据与RT-qPCR结果均具有相同的表达趋势, 表明转录组差异表达基因的鉴定结果是可靠的。

图5 精巢差异表达基因的转录组数据和RT-qPCR结果比较

注: *: 差异显著(<0.05); **: 差异极显著(<0.01)

3 讨论

本研究通过对雄性凡纳滨对虾进行单侧眼柄切除, 显著提高了促雄性腺中基因的表达, 表明眼柄切除一定程度上解除了眼柄内分泌系统中抑制性别发育的因素。在此前提下, 通过对眼柄切除前后对虾的精巢进行比较转录组分析, 鉴定到一系列与性别发育、内分泌、泛素化等过程相关的差异表达基因, 它们可能受到“眼柄-促雄性腺-精巢”内分泌轴调控参与精巢的发育过程。

3.1 性别发育相关基因受“眼柄-促雄性腺-精巢”内分泌轴调控参与精巢发育

促雄性腺表达分泌的胰岛素样促雄性腺素(IAG)除了具有促进雄性甲壳动物动物性别分化的作用外[19],在维持雄性性征及精子发生等方面也发挥关键作用[20]。眼柄切除后,基因表达量显著上升, 这与眼柄内分泌系统中表达分泌该基因的抑制因子如CHH等神经肽激素密切相关[9]。眼柄切除引起的基因表达升高, 对于精巢的发育过程具有促进作用。

Doublesex()是Dmrt家族成员, 它作为性别级联通路下游的关键调控因子, 具有调控性别分化过程的作用[21-23]。在中国明对虾()中,基因表达被沉默后, 显著降低了基因的表达水平, 表明对基因的表达起到正向调控作用[24]。同时, 在个体发育过程中,基因也具有维持性腺发育的功能。多种甲壳物种中的基因在成体中呈现出性别二态性表达特征[25-27]。部分基因在甲壳动物精巢中特异性高表达, 说明其可能参与了精子发生过程[28-29]。在本研究中, 眼柄切除后的精巢内基因表达量显著上调, 表明可能在“眼柄-促雄性腺-精巢”内分泌轴调控下参与精巢发育的过程。

3.2 细胞色素P450酶系基因受“眼柄-促雄性腺-精巢”内分泌轴调控参与精巢发育

在脊椎动物中, 合成类固醇的过程需要细胞色素P450酶系的参与, 例如芳香化酶基因对于脊椎动物性腺分化和发育起了重要作用[30]。在节肢动物中, 已有多个P450家族成员被报道具有调节内源性信号分子(包括蜕皮激素)、信号分子与防御用途化学物质的合成和降解的功能[31]。在甲壳动物中, 细胞色素P450被认为可以合成与代谢各种类固醇激素, 其中蜕皮激素被认为是细胞色素P450最重要的底物[32]。在海洋桡足类飞马哲水蚤()中, 含有较高脂肪储备的雌性个体, 体内往往有着高浓度的20E, 而在这类个体中表达量最高, 表明其参与蜕皮酮合成和脂质储存调节过程[33]。在普通滨蟹()中,也被发现可能具有调节20E合成的作用[34]。

甲壳动物性腺和血淋巴中广泛存在多种类固醇类激素。三疣梭子蟹()的卵巢组织中发现了17-α羟基化孕酮[35], 美洲龙虾()精巢中发现孕酮会被转化为20-α-羟基孕酮[36], 斑节对虾()卵巢中的孕酮可被代谢为20α-dihydroprogesterone[36]。然而, 类固醇激素在甲壳动物发育、生长、性别分化以及繁殖等方面的具体作用以及细胞色素P450是否参与这些类固醇激素合成与代谢都还不明确。本研究发现的基因, 其同源基因最早在对加勒比海眼斑龙虾()中报道, 对黄体酮和睾酮的单加氧反应具有催化作用[37]。及其他P450家族基因在眼柄切除后的显著上调, 说明它们可能受“眼柄-促雄性腺-精巢”内分泌轴调控, 在凡纳滨对虾精巢发育过程中具有重要作用。

3.3 泛素化相关基因在性腺发育中的作用

泛素/蛋白酶体途径(ubiquitin-proteasome system, UPP)在细胞周期调控、细胞器生物发生、组织重塑等许多生化过程中发挥着重要作用[38]。泛素化依赖于3个泛素化酶的协同作用: 泛素激活酶E1以ATP依赖的方式将泛素分子C端赖氨酸(Lys)残基同自身半胱氨酸(Cys)以硫酯键连接, 之后泛素分子通过高能硫酯键连接到泛素偶联酶E2, 最终直接连接到目标蛋白或在泛素连接酶E3酶作用下与靶蛋白通过形成氨基异肽键连接, 从而实现对靶蛋白的标记分类[39]。泛素化调节过程也是可逆的, 这一过程由去泛素化酶(deubiquitinating enzymes, DUBs)介导, 主要分为5个家族: 泛素羧基末端水解酶(ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolases, UCH)家族, 泛素特异性蛋白酶(ubiquitin-specific proteases, USP/ UBP)家族, Otubaim(OTU)家族, Josephin结构域蛋白家族及AB1/MPN/Mov34 metalloenzyme(JAMM)家族[40]。

UPP在性别发育过程中的作用已在多种动物中有报道。在家猪(Sus scrofa domestica)中,编码的泛素激活酶E1参与到了精子发生过程, 在精子获能和顶体功能方面发挥作用[41]。在大鼠()中,特异表达于精原细胞, 其可能通过泛素/蛋白酶体系统来影响精子发生[42]。在小鼠()中, 使用特异性抑制剂PYR-41 处理的卵细胞, 通过干扰常见的泛素化靶蛋白β-catenin, 导致精卵融合后精子体积的增大和染色体减数分裂的阻滞[43]。在秀丽隐杆线虫()中, Cul-2泛素连接酶复合物以Fem-1为识别亚基, 以Fem-2和Fem-3辅因子, 通过蛋白酶体依赖性降解TRA-1实现性别决定的最后一步[44]。线虫基因发挥重要的泛素化功能, 在精子发生、体型调控和性别分化发育等方面发挥作用[45-47],基因突变阻滞了线虫精子的减数分裂过程[48]。在果蝇中, 去泛素化酶Usp9x被发现参与了性腺发育和卵子发生[49]。在甲壳动物中, UPP被认为通过调控蛋白质水解速率, 在性别分化和配子发生过程中起作用[50]。在日本对虾中, 泛素结合酶E2r ()基因在雌雄性腺中的表达呈周期性波动, 暗示着在精子发生和卵子发生过程中发挥重要作用[51]。在斑节对虾中,通过性腺抑制性消减杂交文库分析, 泛素连接酶E2被鉴定为性别相关基因[52]。本研究发现泛素化相关基因ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1、ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2和E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase SH3RF1以及去泛素化酶ubiquitin specific peptidase 21均在眼柄切除后的精巢中发生显著差异表达。结果表明, 泛素/蛋白酶体途径可能在“眼柄-促雄性腺-精巢”内分泌轴的调控下, 在对虾精巢的发育过程中发挥重要作用。

3.4 甲基法尼酯(methyl farnesoate, MF)代谢相关基因在性腺发育中的作用

在甲壳动物中, 由大颚器官(mandibular organ, MO)分泌的MF起到了与昆虫保幼激素(juvenile hormone, JH)类似的作用[53], 在甲壳动物发育、生长、蜕皮和繁殖等过程中发挥功能[54]。在昆虫中, 保幼激素环氧化物水解酶(juvenile hormone epoxide hydrolase, JHEH)主要负责调节保幼激素JH的水平[55]。JHEH可以打开JH环氧环, 生成无生物活性的JH二醇[56], 调节昆虫的变态发育和生殖过程[57]。虽然目前没有证据表明MF会被JHEH降解, 但在中华绒螯蟹()、日本沼虾()和中华新米虾()中都鉴定到基因[58], 其表达量与性成熟状态或蜕皮周期相关[59], 推测其功能依然和MF浓度调节有关。在本研究中,在眼柄切除的精巢组织中发生显著上调表达, 暗示着其受“眼柄-促雄性腺-精巢”内分泌轴调控参与精巢发育过程。

4 结论

本研究通过单侧切除雄性对虾的眼柄, 研究了眼柄内分泌系统对胰岛素样促雄性腺素基因()和精巢内基因表达的影响, 鉴定了精巢中多个与性别发育、内分泌、泛素化等过程相关的差异表达基因。研究结果揭示了“眼柄-促雄性腺-精巢”内分泌轴通过调控促雄性腺中基因及精巢中一系列基因的表达参与精巢发育的过程, 为深入理解甲壳动物精巢发育的分子调控机制提供了重要依据, 对甲壳动物的人工繁育也具有重要指导意义。

[1] HOPKINS P M. The eyes have it: A brief history of crustacean neuroendocrinology[J]. Gen Comp Endocrinol, 2012, 175(3): 357-366.

[2] SKINNER D M. Interacting factors in the control of the crustacean molt cycle1[J]. American Zoologist, 2015, 25(1): 275-284.

[3] 水燕, 史永红, 徐增洪, 等. 眼柄切除快速诱导甲壳动物生长发育研究进展[J]. 广东农业科学, 2013, 40(21): 124-126, 135.

SHUI Yan, SHI Yonghong, XU Zenghong, et al.Advances of growth and development in crustaceans induced by eyestalk ablation[J]. Guangdong Agricultural Sciences, 2013, 40(21): 124-126, 135.

[4] 康现江, 米娅, 刘彬彬, 等. 摘除眼柄对中华绒螯蟹精巢发育及其氨基酸含量的影响[J]. 台湾海峡, 2000, 3: 360-363, 400.

KANG Xianjiang, MI Ya, LIU Binbin, et al. Studies on testis development and its variation of amino acid content inby eyestalk ablation[J]. Journal of Oceanography in Taiwan Strait, 2000, 3: 360- 363, 400.

[5] 崔青曼, 袁春营, 吴婷婷. 眼柄切除及注射黄体酮对中华绒螯蟹幼蟹卵巢发育的影响[J]. 海洋水产研究, 2004, 6: 30-34.

CUI Qingman, YUAN Chunying, WU Tingting. Effects of eyestalk-ablated and injecting progesterone on the Chinese mitten-handed juvenile crab ovarian development[J]. Marine Fisheries Research, 2004, 6: 30-34.

[6] 林琼武, 张黎黎, 吴超, 等. 切除眼柄对日本囊对虾亲虾摄食、性腺发育及能量转化的影响[J]. 厦门大学学报(自然科学版), 2009, 48(6): 915-920.

LIN Qiongwu, ZHANG Lili, WU Chao, et al. Effects of unilateral eyestalk alation on feeding gonadal development and energy conversion ofbroodstock[J]. Journal of Xiamen University (Natural Science), 2009, 48(6): 915-920.

[7] 邓思平, 叶满, 朱春华, 等. 切除眼柄对凡纳滨对虾亲虾卵巢、肝胰腺、血清生化组成的影响[J]. 广东海洋大学学报, 2016, 36(3): 29-34.

DENG Siping, YE Man, ZHU Chunhua, et al. Influence of eyestalk ablation on biochemical composition of ovary, hepatopancreas and serum in Pacific white shrimp,broodstock[J]. Journal of Guangdong Ocean University, 2016, 36(3): 29-34.

[8] LACOMBE C, Grève P, MARTIN G. Overview on the sub-grouping of the crustacean hyperglycemic hormone family[J]. Neuropeptides, 1999, 33(1): 71-80.

[9] GUO Q, LI S, LV X, et al. Sex-biased CHHs and their putative receptor regulate the expression of IAG gene in the shrimp[J]. Front Physiol, 2019, 10: 1525.

[10] LIU A, LIU J, LIU F, et al. Crustacean female sex hormone from the mud crabis highly expressed in prepubertal males and inhibits the development of androgenic gland[J]. Front Physiol, 2018, 9: 924.

[11] 朱春华, 赵光凤, 李广丽, 等. 眼柄粗提物对凡纳滨对虾性分化的影响[J]. 广东海洋大学学报, 2011, 31(1): 23-27.

ZHU Chunhua, ZHAO Guangfeng, LI Guangli, et al. Effects of eyestalk extracts on the sex differentiation on[J]. Journal of Guangdong Ocean University, 2011, 31(1): 23-27.

[12] DE KLEIJN D P, Janssen K P, Waddy S L, et al. Expression of the crustacean hyperglycaemic hormones and the gonad-inhibiting hormone during the reproductive cycle of the female American lobster[J]. J Endocrinol, 1998, 156(2): 291-298.

[13] LAUFER H, JONNA S B A, SAGI A. The role of juvenile hormones in crustacean reproduction[J]. American Zoologist, 1993, 33(3): 365-374.

[14] KHALAILA I, MANOR R, WEIL S, et al. The eyestalk- androgenic gland-testis endocrine axis in the crayfish[J]. Gen Comp Endocrinol, 2002, 127(2): 147-156.

[15] MORAKOT S, CHAROONROJ C, MICHAEL J S, et al. Bilateral eyestalk ablation of the blue swimmer crab,, produces hypertrophy of the androgenic gland and an increase of cells producing insulin-like androgenic gland hormone[J]. Tissue and Cell, 2010, 42(5): 293-300.

[16] CHUNG J S, MANOR R, SAGI A. Cloning of an insulin-like androgenic gland factor (IAG) from the blue crab,: implications for eyestalk regulation of IAG expression[J]. Gen Comp Endocrinol, 2011, 173(1): 4-10.

[17] ROSEN O, MANOR R, WEIL S, et al. An androgenic gland membrane-anchored gene associated with the crustacean insulin-like androgenic gland hormone[J]. J Exp Biol, 2013, 216(Pt 11): 2122-2128.

[18] LIVAK K J, SCHMITTGEN T D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method[J]. Methods, 2001, 25(4): 402-408.

[19] LEVY T, SAGI A. The “IAG-Switch”-A key controlling element in decapod crustacean sex differentiation[J]. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2020, 11: 651.

[20] VENTURA T, MANOR R, AFLAO E D, et al. Temporal silencing of an androgenic gland-specific insulin- like gene affecting phenotypical gender differences and spermatogenesis[J]. Endocrinology, 2009, 150(3): 1278- 1286.

[21] KATO Y, KOBAYASHI K, WATANABE H, et al. Environmental sex determination in the branchiopod crustacean: deep conservation of agene in the sex-determining pathway[J]. PLoS Genet, 2011, 7(3): e1001345.

[22] JIANBO Z, LINA C, YONGYI J, et al. Identification and functional analysis of thegene in the redclaw crayfish,[J]. Gene Expression Patterns, 2020, 37: 119129.

[23] BURTIS K C, BAKER B S.doublesex gene controls somatic sexual differentiation by producing alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding related sex- specific polypeptides[J]. Cell, 1989, 56(6): 997-1010.

[24] GUO Q, LI S, LV X, et al. A putative insulin-like androgenic gland hormone receptor gene specifically expressed in male Chinese shrimp[J]. Endocrinology, 2018, 159(5): 2173-2185.

[25] AMTERAT ABU ABAYED F, MANOR R, AFLALO E D, et al. Screening forgenes from embryo to matureprawns[J]. Gen Comp Endocrinol, 2019, 282: 113205.

[26] YU Y Q, MA W M, ZENG Q G, et al. Molecular cloning and sexually dimorphic expression of twogenes in the giant freshwater prawn,[J]. Agricultural Research, 2014, 3(2): 181-191.

[27] CHANDLER J C, FITZGIBBON Q P, Smith G, et al. Y-linked iDmrt1 paralogue (iDMY) in the eastern spiny lobster,: The first invertebrate sex-linked Dmrt[J]. Dev Biol, 2017, 430(2): 337-345.

[28] ZHANG E F, QIU G F. A novelgene is specifically expressed in the testis of Chinese mitten crab,[J]. Dev Genes Evol, 2010, 220(5-6): 151-159.

[29] 俞炎琴. 罗氏沼虾中性别发育相关基因和基因的分子特征和功能研究[D]. 杭州: 浙江大学, 2013.

YU Yanqin. The molecular characterization and functional analysis of sexual development related genesandin the prawn[D].Hangzhou: Zhejiang University, 2013.

[30] MATSUMOTO Y, BUEMIO A, CHU R, et al. Epigenetic control of gonadal aromatase (cyp19a1) in temperature-dependent sex determination of red-eared slider turtles[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(6): e63599.

[31] DERMAUW W, VAN LEEUWEN T, FEVEREISEN R. Diversity and evolution of the P450 family in arthropods[J]. Insect Biochem Mol Biol, 2020, 127: 103490.

[32] MYKLES D L. Ecdysteroid metabolism in crustaceans[J]. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 2011, 127(3-5): 196-203.

[33] HANSEN B H, ALTIN D, HESSEN K M, et al. Expression of ecdysteroids and cytochrome P450 enzymes during lipid turnover and reproduction in(Crustacea: Copepoda)[J]. Gen Comp Endocrinol, 2008, 158(1): 115-121.

[34] REWITZ K, STYRISHAVE B, ANDERSEN O. CYP330A1 and CYP4C39 enzymes in the shore crab: sequence and expression regulation by ecdysteroids and xenobiotics[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2003, 310(2): 252-260.

[35] TESHIMA S, KANAZAWA A. Bioconversion of progesterone by the ovaries of crab,[J]. Gen Comp Endocrinol, 1971, 17(1): 152-157.

[36] BURNS B G, SANGALANG G B, FREEMAN H C, et al. Bioconversion of steroids by the testes of the American lobster,, in vitro[J]. Gen Comp Endocrinol, 1984, 54(3): 422-428.

[37] JAMES M O, BOYLE S M. Cytochromes P450 in crustacea[J]. Comp Biochem Physiol C Pharmacol Toxicol Endocrinol, 1998, 121(1-3): 157-72.

[38] HERSHKO A, CIECHANOVER A. The ubiquitin system[J]. Annu Rev Biochem, 1998, 67: 425-429.

[39] 董雯, 郭宁, 宋伦. 蛋白质的泛素化修饰在细胞应激反应中的作用[J]. 生物技术通讯, 2010, 21(5): 727-730.

DONG Wen, GUO Ning, SONG Lun. Role of protein ubiquitination in mediating the cellular stress response[J]. Letters in Biotechnology, 2010, 21(5): 727-730.

[40] 刘文斌. 去泛素化酶研究进展[J]. 武汉轻工大学学报, 2016, 35(3): 1-12.

LIU Wenbin. Proceeding of deubiquitinase study[J]. Journal of Wuhan Polytechnic University, 2016, 35(3): 1-12.

[41] YI Y J, ZIMMERMAN S W, MANANDHAR G, et al. Ubiquitin-activating enzyme (UBA1) is required for sperm capacitation, acrosomal exocytosis and sperm-egg coat penetration during porcine fertilization[J]. Int J Androl, 2012, 35(2): 196-210.

[42] DU Y, LIU M L, JIA M C. Identification and characterization of a spermatogenesis-related gene Ube1 in rat testis[J]. Sheng Li Xue Bao, 2008, 60(3): 382-390.

[43] YOSHIDA K, KANG W, NAKAMURA A, et al. Ubiquitin- activating enzyme E1 inhibitor PYR-41 retards sperm enlargement after fusion to the egg[J]. Reprod Toxicol, 2018, 76: 71-77.

[44] STAROSTINA N G, LIM J M, SCHVARZSTEIN M, et al. A CUL-2 ubiquitin ligase containing three FEM proteins degrades TRA-1 to regulatesex determination[J]. Dev Cell, 2007, 13(1): 127-139.

[45] KAMATH R S, FRASER A G, DONG Y, et al. Systematic functional analysis of thegenome using RNAi[J]. Nature, 2003, 421(6920): 231- 237.

[46] JONES D, CROWE E, STEVENS T A, et al. Functional and phylogenetic analysis of the ubiquitylation system in: ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, ubiquitin-activating enzymes, and ubiquitin-like proteins[J]. Genome Biol, 2002, 3(1): Research0002.

[47] SÖNNICHSEN B, KOSKI L B, WALSH A, et al. Full- genome RNAi profiling of early embryogenesis in[J]. Nature, 2005, 434(7032): 462- 469.

[48] KULKARNI M, SMITH H E. E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme UBA-1 plays multiple roles throughoutdevelopment[J]. PLoS Genet, 2008, 4(7): e1000131.

[49] NOMA T, KANAI Y, KANAI-AZUMA M, et al. Stage- and sex-dependent expressions of Usp9x, an X-linked mouse ortholog of drosophila fat facets, during gonadal development and oogenesis in mice[J]. Gene Expr Patterns, 2002, 2(1-2): 87-91.

[50] 韩坤煌, 张子平, 王艺磊, 等. Cyclin-CDK-CKI及UPP参与生殖调控及在甲壳动物性腺发育中的研究进展[J]. 生物技术通报, 2010, 7: 48-54.

HAN Kunhuang, ZHANG Ziping, WANG Yilei, et al. Cyclin-CDK-CKI and UPP participate in the regulation of reproduction and the progression of gonad development in crustacean[J]. Biotechnology Bulletin, 2010, 7: 48-54.

[51] SHEN B, ZHANG Z, WANG Y, et al. Differential expression of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2r in the developing ovary and testis of penaeid shrimp[J]. Mol Biol Rep, 2009, 36(5): 1149- 1157.

[52] LEELATANAWIT R, SITTIKANKEAW K, YOCAWI BUN P, et al. Identification, characterization and expression of sex-related genes in testes of the giant tiger shrimp[J]. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol, 2009, 152(1): 66-76.

[53] NAGARAJU G P C. Is methylfarnesoate a crustacean hormone[J]. Aquaculture (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2007, 272(1-4): 39-54.

[54] ELLEN H, ERNEST S C. Methyl farnesoate: crustacean juvenile hormone in search of functions[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 1997, 117(3): 347- 356.

[55] TUSUN A, LI M, LIANG X, et al. Juvenile hormone epoxide hydrolase: a promising target for hemipteran pest management[J]. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7(1): 789.

[56] ANURAG A, ERICA J C, ANTHONY J Z. Tissue and stage-specific juvenile hormone esterase (JHE) and epoxide hydrolase (JHEH) enzyme activities and Jhe transcript abundance in lines of the cricketartificially selected for plasma JHE activity: Implications for JHE microevolution[J]. Journal of Insect Physiology, 2008, 54(9): 1323-1331.

[57] MARLA R S, ROE R M. A partition assay for the simultaneous determination of insect juvenile hormone esterase and epoxide hydrolase activity[J]. Analytical Biochemistry, 1988, 169(1): 81-88.

[58] YUNG W S, NATHAN J K, ZHE Q, et al. Identification of putative ecdysteroid and juvenile hormone pathway genes in the shrimp[J]. General and Comparative Endocrinology, 2015, 214: 167-176.

[59] 张佳鑫, 徐敏杰, 黄根勇, 等. 正常与性早熟中华绒螯蟹的Y-器官转录组分析[J]. 水产学报, 2017, 41(11): 1667-1679.

ZHANG Jiaxin, XU Minjie, HUANG Genyong, et al. Transcriptome sequencing and functional analysis of Y-organs between normal and precocious Chinese mitten crabs ()[J]. Journal of Fisheries of China, 2017, 41(11): 1667-1679.

Regulatory mechanisms of the eyestalk-androgenic gland-testis endocrine axis on testis development in

CHEN Kang-xuan1, 2, LI Shi-hao1, LI Fu-hua1

(1. Key Laboratory of Experimental Marine Biology, Institute of Oceanology Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China; 2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China)

The neuroendocrine system in crustacean eyestalks regulates the reproduction process. According to previous studies, the eyestalk–androgenic gland (AG)–testis endocrine axis regulates testis development in decapod crustacean species. However, the underlying molecular mechanism remains largely unknown. The Pacific white shrimp () was used in this study to investigate how unilateral eyestalk ablation regulates the expression of insulin-like AG hormones () in AG, and genes in the testis. According to the results, after unilateral eyestalk ablation, theexpression level was significantly upregulated. The transcriptome data of shrimp testis before and after unilateral eyestalk ablation were compared. A total of 267 genes were identified as differentially expressed genes (DEGS). Functional analysis showed that Some genes involved in gonad development and endocrine regulation, such as Doublesex (), juvenile hormone epoxide hydrolase (), genes related to the cytochrome P450 enzyme system, and genes related to the ubiquitylation system, were significantly upregulated. The expression of several DEGs were confirmed using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), which revealed that their expression trends were consistent with those in the transcriptome data, implying that the transcriptome data were reliable. The results indicated that the endocrine system in eyestalk influenced testis development by regulating the expression ofin AG, which in turn regulated the expression of,, and genes in the endocrine and ubiquitylation systems in the testis. The results not only contribute to a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms regulating testis development but also provide significant direction for the artificial reproduction of crustaceans.

penaeid shrimp; eyestalk; insulin-like androgenic gland hormone; testis development

May 11, 2021

S917.4

A

1000-3096(2021)11-0062-11

10.11759/hykx20210511001

2021-05-11;

2021-05-19

国家重点研发计划项目(2018YFD0900202); 中以(NSFC-ISF)国际(地区)合作与交流项目(31861143047)

[The National Key Research and Development Program of China, No. 2018YFD0900202; the Joint NSFC-ISF Research Program, No. 31861143047]

陈康轩(1996—), 男, 山东青岛人, 硕士研究生, 主要从事海洋生物学研究, 电话: 13717691662, E-mail: 15561576203@163. com; 李富花(1965—),通信作者, 电话: 0532-82898836, E-mail: fhli@qdio.ac.cn

(本文编辑: 谭雪静)