Diabetes patients with comorbidities had unfavorable outcomes following COVID-19:A retrospective study

2021-11-25ShunKuiLuoWeiHuaHuZhanJinLuChangLiYaMengFanQiJianChenZaiShuChenJianFangYeShiYanChenJunLuTongLingLingWangJinMeiHongYunLu

Shun-Kui Luo, Wei-Hua Hu, Zhan-Jin Lu, Chang Li, Ya-Meng Fan, Qi-Jian Chen, Zai-Shu Chen, Jian-Fang Ye,Shi-Yan Chen, Jun-Lu Tong, Ling-Ling Wang, Jin Mei, Hong-Yun Lu

Shun-Kui Luo, Zhan-Jin Lu, Jian-Fang Ye, Shi-Yan Chen, Jun-Lu Tong, Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, the Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Zhuhai 519000, Guangdong Province, China

Wei-Hua Hu, Department of Respiratory Medicine, The First Hospital of Jingzhou, Clinical Medical College, Yangtze University, Jingzhou 434000, Hubei Province, China

Chang Li, Department of Cardiology, Hubei No. 3 People’s Hospital of Jianghan University,Wuhan 430033, Hubei Province, China

Ya-Meng Fan, School of Health Sciences, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430071, Hubei Province,China

Qi-Jian Chen, Department of Emergency Medicine, The Fifth Hospital in Wuhan, Wuhan 430050, Hubei Province, China

Zai-Shu Chen, People's Hospital of Jiayu County, Jiayu 437200, Hubei Province, China

Ling-Ling Wang, Department of Gerontology, The Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Zhuhai 519000, Guangdong Province, China

Jin Mei, Anatomy Department, Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou 325035, Zhejiang Province, China

Jin Mei, Central Laboratory, Ningbo First Hospital of Zhejiang University, Ningbo 315010,Zhejiang Province, China

Hong-Yun Lu, Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Zhuhai Hospital Affiliated with Jinan University, Zhuhai 519000, Guangdong Province, China

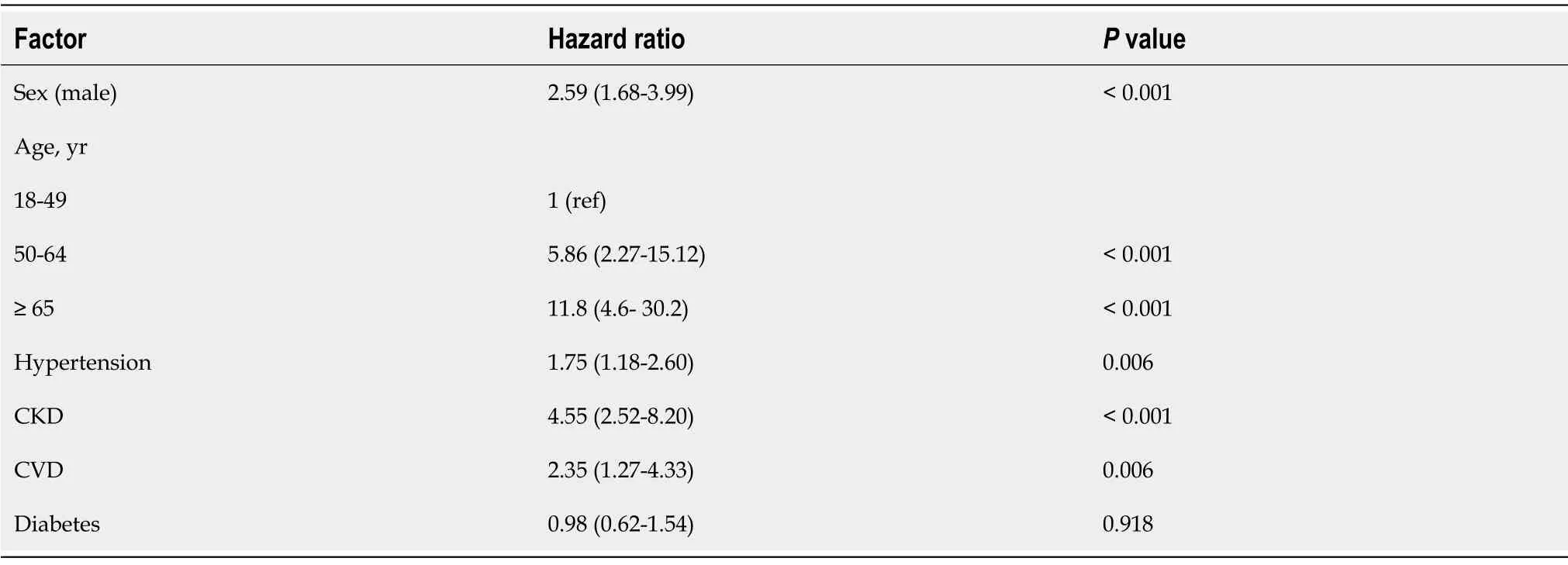

Abstract BACKGROUND Previous studies have shown that diabetes mellitus is a common comorbidity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), but the effects of diabetes or anti-diabetic medication on the mortality of COVID-19 have not been well described.AIM To investigate the outcome of different statuses (with or without comorbidity) and anti-diabetic medication use before admission of diabetic after COVID-19.METHODS In this multicenter and retrospective study, we enrolled 1422 consecutive hospitalized patients from January 21, 2020, to March 25, 2020, at six hospitals in Hubei Province, China. The primary endpoint was in-hospital mortality. Epidemiological material, demographic information, clinical data, laboratory parameters,radiographic characteristics, treatment and outcome were extracted from electronic medical records using a standardized data collection form. Most of the laboratory data except fasting plasma glucose (FPG) were obtained in first hospitalization, and FPG was collected in the next day morning. Major clinical symptoms, vital signs at admission and comorbidities were collected. The treatment data included not only COVID-19 but also diabetes mellitus. The duration from the onset of symptoms to admission, illness severity, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and length of hospital stay were also recorded. All data were checked by a team of sophisticated physicians.RESULTS Patients with diabetes were 10 years older than non-diabetic patients [(39 - 64) vs(56 - 70), P < 0.001] and had a higher prevalence of comorbidities such as hypertension (55.5% vs 21.4%, P < 0.001), coronary heart disease (CHD) (9.9% vs 3.5%, P < 0.001), cerebrovascular disease (CVD) (3% vs 2.2%, P < 0.001), and chronic kidney disease (CKD) (4.7% vs 1.5%, P = 0.007). Mortality (13.6% vs 7.2%,P = 0.003) was more prevalent among the diabetes group. Further analysis revealed that patients with diabetes who took acarbose had a lower mortality rate(2.2% vs 26.1, P < 0.01). Multivariable Cox regression showed that male sex[hazard ratio (HR) 2.59 (1.68 - 3.99), P < 0.001], hypertension [HR 1.75 (1.18 - 2.60),P = 0.006), CKD [HR 4.55 (2.52-8.20), P < 0.001], CVD [HR 2.35 (1.27 - 4.33), P =0.006], and age were risk factors for the COVID-19 mortality. Higher HRs were noted in those aged ≥ 65 (HR 11.8 [4.6 - 30.2], P < 0.001) vs 50-64 years (HR 5.86[2.27 - 15.12], P < 0.001). The survival curve revealed that, compared with the diabetes only group, the mortality was increased in the diabetes with comorbidities group (P = 0.009) but was not significantly different from the noncomorbidity group (P = 0.59).CONCLUSION Patients with diabetes had worse outcomes when suffering from COVID-19;however, the outcome was not associated with diabetes itself but with comorbidities. Furthermore, acarbose could reduce the mortality in diabetic.

Key Words: Diabetes; Coronavirus disease 2019; Mortality; Risk factors; Acarbose

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become an ongoing pandemic and has caused considerable mortality worldwide[1]. Diabetes is a common comorbidity,especially in elderly patients, but the effects of diabetes or anti-diabetic medication on the severity and mortality of COVID-19 have not been well described. As of April 27,2021, nearly 150 million COVID-19 cases had been confirmed around the world, and more than 3 million patients died of COVID-19 (https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019). Well-controlled blood glucose (3.9-10.0 mmol/L) in preexisting diabetes was associated with a significant reduction in the composite adverse outcomes and death of patients with COVID-19[2]. Patients with diabetes often have several comorbidities, and previous research has revealed that hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic kidney disease(CKD), cardiovascular disease and cerebrovascular disease (CVD) are also associated with worse outcomes in patients suffering from COVID-19[3-6]. However, few studies have described the outcome of different comorbidity statuses of patients with diabetes after infection with COVID-19. In addition, few studies have focused on whether antidiabetic medication would influence the outcome of patients with preexisting diabetes who suffer from COVID-19. Considering this, we performed a multicenter study to investigate the outcome of different statuses (with or without comorbidity) and antidiabetic medication before admission of patients with diabetes with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and participants

This is a multicenter, observational, retrospective, real-world study that included adult inpatients from six designated tertiary centers (Supplementary Table 1) between January 21 and March 25, 2020. A total of 1422 patients with COVID-19 were screened for this study (Figure 1). All patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 in accordance with WHO interim guidance.

Figure 1 Flow chart of patient recruitment.

Data collection

Epidemiological material, demographic information, clinical data, laboratory parameters, radiographic characteristics, treatment and outcome were extracted from electronic medical records using a standardized data collection form. Most of the laboratory data except fasting plasma glucose (FPG) were obtained in first hospitalization, and FPG was collected in the next day morning. Major clinical symptoms, vital signs at admission and comorbidities were collected. The treatment data included not only COVID-19 but also diabetes mellitus. The duration from the onset of symptoms to admission, illness severity, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and length of hospital stay were also recorded. All data were checked by a team of sophisticated physicians.Diabetes was defined as a history record of diabetes and the use of anti-diabetic medication; otherwise, newly diagnosed diabetes was based on the level of fasting plasma glucose (FPG) (≥ 7.0 mmol/L), random plasma glucose (≥ 11.1 mmol/L),glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥ 6.5% and classic symptoms of hyperglycemia during hospital stay (as the oral glucose tolerance test may lead to hyperglycemia and then to worsening of a COVID-19 patient’s illness, it was not used for diagnosis of diabetes in our study[7]). Hypertension was defined by a history of hypertension, the use of anti-hypertensive drugs, or the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute criteria[8]. Coronary heart disease was defined by a history of coronary heart disease. CVD was defined by a history of CVD. ARDS was defined according to the Berlin definition[9]. Acute kidney injury (AKI) was diagnosed according to the KDIGO (Kidney Disease:Improving Global Outcomes) clinical practice guidelines[10]. Acute cardiac injury (ACI) was reported if serum levels of myocardial injury biomarkers were higher than the upper limit of normal[2]. The criteria for classification of COVID-19 severity were according to the Diagnosis and Treatment Protocol for COVID-19 (Trial Version 8)[11]. We divided the patients into two groups:the non-severe group (mild and general types) and the severe group (severe and critical types).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality after admission. Secondary outcomes were ICU admission and incidence of SARS-CoV-2-related complications, including ARDS, AKI, ACI, secondary infection, shock and hypoproteinemia.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were described as the mean ± SD or median (IQR). Categorical variables were calculated as frequencies and percentages with available data. The differences in continuous variables among groups were assessed using the independent samplet-test or one-way ANOVA for normally distributed continuous variables or the Mann-WhitneyUtest or Kruskal-WallisHtest for skewed continuous variables. Pearson’sχ2test and Fisher’s exact test were performed for unordered categorical variables. The Mann-WhitneyUtest or the Kruskal-WallisHtest was used for ordered categorical variables. To explore the risk factors associated with mortality,multivariable Cox regression models were performed. The Kaplan-Meier plot was performed to compare the survival probability for the diabetes and non-diabetes groups and among the patients with no comorbidities, only diabetes and diabetes with comorbidities by log-rank test. Additionally, we did not process the missing data. The statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS (version 25.0). A two-sidedPvalue less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Yameng Fan from Wuhan University.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics and laboratory results of 1331 patients with COVID-19 divided into different groups

The characteristics of this study population at baseline are given in Table 1. The median age was 54 years old (39-64) and 64 years old (56-70) in the non-diabetes anddiabetes groups, respectively. Comorbidities such as hypertension (55.5%vs21.4%),coronary heart disease (9.9%vs3.5%), CVD (7.3%vs2.2%), and CKD (4.7%vs1.5%)were significantly more prevalent in the diabetes group. Mean systolic blood pressure(SBP) was higher in the diabetes group. Moreover, decreased blood oxygen saturation(lower than 93%) occurred more frequently in the diabetes groupvsthe non-diabetes group (19.8%vs19.6%) on admission. Chest CT scan revealed that the incidence of bilateral lesions was higher (94%vs80.1%) in the diabetes group than in the nondiabetes group.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of 1331 coronavirus disease 2019 patients divided into different groups

Data are expressed as n (%), mean ± SD or median (IQR). P values were calculated by t Test, Mann-Whitney U test, χ2 test, Fisher's exact test, One-Way ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis H test as appropriate.1Comparing groups of diabetes and non-diabetes patients.2Comparing groups of non-comorbidity, only diabetes and diabetes with comorbidities.dMann-Whitney U test comparing all subcategories. Compared with diabetes only group.aP < 0.05.bP < 0.05.cP < 0.001.CHD:Coronary heart disease; CKD:Chronic kidney disease; COPD:Chronic obstructive pulmonary diseas; CVD:Cerebrovascular diseasee.

There were numerous differences in laboratory results between the diabetes group and the non-diabetes group with COVID-19 (Table 2). FPG levels were significantly higher in the diabetes group than in the non-diabetes group, as expected, with higher levels of HbA1c. Patients with diabetes had a higher white blood cell count (WBC),neutrophil count (NEU), neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and C-reactive protein(CRP) and a lower lymphocyte count (LY) than the non-diabetic group. These results revealed that diabetes represented more severe inflammation. The percentage of high levels of prothrombin time (PT) and D-dimer among the diabetes group was higher than that among the non-diabetes group. The serum level of albumin (ALB) was lower in the diabetes group than in the non-diabetes group. Meanwhile, urea nitrogen(BUN), a marker of kidney function, was higher in the diabetes group. Non-diabetes participants had significantly lower serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase. Compared with the non-diabetes group, the diabetes group had higher levels of total cholesterol(TCH) and lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C).

In addition, a between-group comparison with only the diabetes group was performed. The baseline characteristics and radiological findings are also summarized in Table 1. Patients with diabetes with comorbidities were the oldest among the three groups. There was a significant difference in blood oxygen saturation and respiratory rate among the three groups but no significant differences in the comparison of the non-comorbidity group and only diabetes group or the comparison of the diabetes only group and diabetes with comorbidities group. Chest CT scans indicated that the diabetes only group had more incidences of bilateral lesions than the non-comorbidity group.

Although there were numerous differences in laboratory findings among the noncomorbidity group, diabetes only group and diabetes with comorbidities group(Table 2), only ten items had statistical significance between the non-comorbidity group and diabetes only group, including ALB, sodium, BUN, CRP, and HDL-C, as well as FPG and HbA1c, as expected. These results combined with oxygen saturation indicated that there was no difference in cardiac, liver, lung and coagulation function between the groups.

Table 2 Laboratory results of 1331 coronavirus disease 2019 patients divided into different groups

Data are expressed as n (%), mean ± SD or median (IQR). P values were calculated by t Test, Mann-Whitney U test, χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test, One-Way ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis H test as appropriate.1Comparing groups of diabetes and non-diabetes patients.2Comparing groups of non-comorbidity, only diabetes and diabetes with comorbidities.3Mann-Whitney U test comparing all subcategories.Compared with diabetes only group,aP < 0.05.bP < 0.05.cP < 0.001.ALB:Albumin; ALP:Alkaline phosphatase; ALT:Alanine aminotransferase; AST:Aspartate aminotransferase; BUN:Urea nitrogen; CK:Creatine kinase;CRP:C reactive protein; FPG:Fasting plasma glucose; Hb:Hemoglobin; HbA1C:Glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL-C:High density lipoprotein cholesterol;Hs-cTnI:Hypersensitive troponin I; LDH:Lactate dehydrogenase; LDL-C:Low density lipoprotein cholesterol; LY:Lymphocyte; NEUT:Neutrophil; NLR:Neutrophil lymphocyte ratio; PCT:Procalcitonin; PLT:Platelet; PT:Prothrombin time; TBIL:Total bilirubin; TCH:Total cholesterol; TG:Triglyceride; UA:Uric acid; WBC:White blood cell.

FPG and HbA1c in the diabetes only group and diabetes with comorbidities group were almost at the same level. Compared with the diabetes only group, the diabetes with comorbidities group had a lower LY and a higher NLR and CRP, which represented a more severe inflammatory response.

Treatment and outcome of 1331 patients with COVID-19 divided into different groups

As shown in Table 3, 1223 of the 1331 patients (91.9%) were discharged from the hospital; the rate of mortality of the diabetes group was higher than that of the nondiabetes group (13.6%vs7.2%). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for all-cause mortality in patients with COVID-19 is shown in Figure 2. The overall survival rate was significantly lower in the diabetes group (log-rankP< 0.01, Figure 2A). Comparedwith non-diabetes patients, more patients with diabetes reported severe cases (34.6%vs21.7%). The diabetes group had a higher rate of ARDS (11%vs5.7%) and hypoproteinemia (15%vs6.5%).

The treatment and primary outcome of the non-comorbidity group and diabetes only group were not different (Table 3), and the results for all-cause mortality were similar in both groups (log-rankP= 0.59) (Figure 2B). Regarding the secondary endpoint, there was no difference between the groups except for hypoproteinemia(5.0%vs16.9%). Likewise, there was a similar frequency of COVID-19 pharmacological therapy in the diabetes only patientsvsdiabetes with comorbidities patients; however,the latter was more likely to receive mechanical ventilation (10.8%vs18.3%), had a higher incidence of mortality (4.6%vs18.3%), greater likelihood of shock (0vs1.6%)and more severe cases (21.5%vs41.3%).

Figure 2 Kaplan-Meier survival curves of in-hospital mortality among patients with coronavirus disease 2019.

Table 3 Treatments and outcomes of 1331 coronavirus disease 2019 patients divided into different groups

Clinical characteristics and laboratory results of diabetic survivors and non-survivors with COVID-19

Diabetic survivors (n= 165) and non-survivors (n= 26) shared basic characteristics except for decreased blood oxygen saturation (10.9%vs26.9%) and rapid breathing(18.2%vs26.9%), which were more frequent in non-survivors (Supplementary Table 2), indicating that the latter had severe lung dysfunction. There were numerousdifferences in laboratory results between diabetic survivors and non-survivors with COVID-19 that reflected the functions of different organs and systems(Supplementary Table 2). Diabetic non-survivors had higher WBC, NEU, NLR, CRP,and IL-6 and lower LY, reflecting that mortality patients had severe inflammatory responses. Serum levels of PT, D-dimer, ALT, AST, BUN, creatinine, CK, and LDH were all significantly higher in non-survivors (Table 4), which reflected more severe coagulation, liver, kidney, and cardiac dysfunction. Diabetic non-survivors reported higher average FPG compared with survivors.

Table 4 Laboratory results of diabetic survivors and non-survivors with coronavirus disease 2019

Data are expressed as n (%), mean ± SD or median (IQR). P values were calculated by t Test, Mann-Whitney U test, χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test as appropriate.1Mann-Whitney U test comparing all subcategories.P:Comparing groups of diabetic survivors and non-survivors; ALB:Albumin; ALP:Alkaline phosphatase; ALT:Alanine aminotransferase; AST:Aspartate aminotransferase; BUN:Urea nitrogen; CK:Creatine kinase; CRP:C reactive protein; FPG:Fasting plasma glucose; Hb:Hemoglobin; HbA1C:Glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL-C:High density lipoprotein cholesterol; Hs-cTnI:Hypersensitive troponin I; LDH:Lactate dehydrogenase; LDL-C:Low density lipoprotein cholesterol; LY:Lymphocyte; NEUT:Neutrophil; NLR:Neutrophil lymphocyte ratio; PCT:Procalcitonin; PLT:Platelet; PT:Prothrombin time;TBIL:Total bilirubin; TCH:Total cholesterol; TG:Triglyceride; UA:Uric acid; WBC:White blood cell.

Treatment and outcome of diabetic survivors and non-survivors with COVID-19

Undoubtedly, higher proportions of complications, including ARDS (3.0vs61.5%),ACI (5.5%vs26.9%), shock (0vs11.5%), secondary infection (6.1%vs46.2%), AKI (0.6%vs7.7%) and coagulopathy (15.8%vs38.5%), were found in non-survivors (Table 5).Likewise, the non-survivor group had a greater incidence of severe cases (33.7%vs100%) and ICU admission (6.7%vs42.3%) and was more likely to receive corticosteroids (33.3%vs73.1%). There was a significantly lower frequency of hypoglycemic medication in diabetic non-survivorsvsdiabetic survivors, including metformin(30.9%vs11.5%), sulfonylurea (21.8%vs3.8%) and acarbose (45.5%vs7.7%), which might be related to controlled blood glucose.

Table 5 Treatments and outcomes of diabetic survivors and non-survivors with coronavirus disease 2019

Clinical characteristics, laboratory results, treatment and outcome of patients with diabetes with COVID-19 using metformin and matched non-metformin users

Of 191 patients with diabetes with COVID-19, 54 cases were using metformin, and after sex and age matching, there were 50 patients using metformin and 50 sex- and age-matched non-metformin users. The frequency of fever (54%vs78%) and fatigue(38%vs18%) showed significant differences in clinical characteristics between patients with diabetes with COVID-19 using metformin and matched non-metformin users(Supplementary Table 3). Laboratory findings (Table 6) revealed that metformin users had lower levels of LDH and FPG; however, the distribution of glucose was similar.The results that referred to liver, kidney, cardiac, coagulation and inflammatory response function were not statistically significant. The primary outcome and secondary outcome of patients who used metformin were comparable to matched nonmetformin users (Table 7). The former group showed a higher need for antivirals (98%vs84%) and antibiotics (90%vs74%). Insulin (52.0%vs20%), sulfonylurea (36.0%vs2%), acarbose (56.0%vs6%), and thiazolidinedione (12%vs0) were also applied significantly more frequently to the individuals using metformin.

Clinical characteristics, laboratory results, treatment and outcome of patients with diabetes with COVID-19 using acarbose and matched non-acarbose users

Of 191 patients with diabetes with COVID-19, 77 cases were treated with acarbose, and after sex and age matching, there were 46 patients treated with acarbose and 46 sexand age-matched non-acarbose users. Supplementary Table 3 shows that the length of symptom onset to hospital admission was longer in the acarbose group than in the matched non-acarbose group, which indicated that the symptoms in the former patients might be relatively mild. Notably, some inflammatory response-related laboratory results, such as WBC, NLR, and CRP, were significantly lower in the acarbose group (Table 6). Furthermore, these differences were not related to glucose control, as the serum level of glucose in both groups was comparable.

Table 6 Laboratory results of diabetic coronavirus disease 2019 patients using metformin or acarbose and matched non-metformin or non-acarbose inhibitor user

Data are expressed as n (%), mean ± SD or median (IQR). P values were calculated by t Test, Mann-Whitney U test, χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test as appropriate.Comparison of metformin users and non-users:aP < 0.05.bP < 0.01.Comparison of acarbose users and non-users:cP < 0.05.dP < 0.01.ALB:Albumin; ALP:Alkaline phosphatase; ALT:Alanine aminotransferase; AST:Aspartate aminotransferase; BUN:Urea nitrogen; CK:Creatine kinase;CRP:C reactive protein; FPG:Fasting plasma glucose; Hb:Hemoglobin; HbA1C:Glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL-C:High density lipoprotein cholesterol;Hs-cTnI:Hypersensitive troponin I; LDH:Lactate dehydrogenase; LDL-C:Low density lipoprotein cholesterol; LY:Lymphocyte; NEUT:Neutrophil; NLR:Neutrophil lymphocyte ratio; PCT:Procalcitonin; PLT:Platelet; PT:Prothrombin time; TBIL:Total bilirubin; TCH:Total cholesterol; TG:Triglyceride; UA:Uric acid; WBC:White blood cell.

The mortality rate (2.2%vs26.1%) was lower in the acarbose group (Table 7), as were the rates of ARDS (2.2%vs17.4%) and shock (2.2%vs21.7%). At the same time,patients who were treated with acarbose indicated a lower need for treatment with corticosteroids (26.1%vs47.8%), immunoglobin (23.9%vs47.8%), mechanical ventilation (6.5%vs21.7%), and insulin (50.0%vs84.8%).

Table 7 Treatments and outcomes of diabetic coronavirus disease 2019 patients using metformin and matched non-metformin,acarbose and matched non-acarbose

Independent risk factors for mortality of patients with COVID-19

Among the 1131 included patients, multivariable Cox regression (Table 8) showed that male [hazard ratio (HR) 2.59, 95%CI 1.63-3.99], hypertension (HR 1.75, 95%CI 1.18-2.6),CKD (HR 4.55, 95%CI 2.52-8.20), and CVD (HR 2.35, 95%CI 1.27-4.33) were risk factors for COVID-19 mortality. Age was also a risk factor for COVID-19 mortality. However,diabetes alone was not an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with COVID-19.

Table 8 Multivariate COX regression analysis on the risk factors associated with mortality of 1331 coronavirus disease 2019 patients

DISCUSSION

A number of studies have demonstrated that patients with diabetes have a higher risk of mortality from COVID, as well as a greater risk of developing more severe cases[4,7,12,13]. Guoet al[13] reported that diabetes was a risk factor for the progression and prognosis of COVID-19. However, Shiet al[14] pointed out that diabetes was not independently associated with COVID mortality, while commonalities, such as hypertension and cardiovascular disease, played more important roles in contributing to the in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19, which was relatively limited in size. In this study, which had relatively rich clinical data, we found that diabetes alone was not an independent risk factor for in-hospital mortality from COVID-19, but comorbidities such as hypertension and CKD were risk factors; this result was consistent with a previous study[14]. Partially consistent with previous studies, our study found that compared with non-diabetic patients, patients with diabetes with COVID-19 were older, had worse outcomes, including a higher rate of mortality,severe cases and ARDS, and presented severe inflammatory response, lung and coagulation dysfunction[7,13,15]. In this study, up to 88% of diabetic patients were greater than or equal to 50 years of age, more over, older age was an independent risk factor of mortality in COVID-19, which was consistent with previous studies[3,14].Additionally, patients with diabetes had increased levels of urea nitrogen and decreased levels of albumin. These abnormalities indicated that COVID-19 may be associated with progressive organ injury in patients with diabetes. Preexisting hypertension, CHD, CVD, and CKD had higher frequencies in the diabetic group.Recent studies reported that patients with cardiovascular hypertension, CKD, and CVD were more likely to develop severe cases[4,6,16], so we compared patients with diabetes and COVID-19 without comorbidity and patients with COVID-19 without any comorbidity to identify whether diabetes without comorbidity was a risk factor for COVID-19. In our study, there was no difference in the outcome between the noncomorbidity group and the diabetes only group. Shiet al[16] reported that even thoughpatients with COVID-19 with diabetes had worse outcomes, it was not independentlyassociated with in-hospital death, which was consistent with our results. In addition,most laboratory results were comparable between the non-comorbidity group and the diabetes only group, except for CRP, albumin, sodium, urea nitrogen, HDL-C and, of course, blood glucose. CRP is an inflammatory biomarker that is related to glucose homoeostasis, obesity and atherosclerosis[17] and was independently related to insulin sensitivity[18]. In addition, insulin resistance was a main characteristic of type 2 diabetes; since CRP was related to the chronic inflammatory situation, and the levels of WBC, NEU, and LY, which reflected the acute infection with the disease pathogen,were not statistically significant, we inferred that diabetes itself did not increase the degree of inflammation after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Patients with diabetes with comorbidities were more seriously ill when compared with the diabetes only group and non-comorbidity group. The mortality was higher in the diabetes with comorbidities group, but the difference between both diabetes groups had no relation to FPG because the median FPG in both diabetes groups was comparable. Patients with diabetes with comorbidity were 10 years older than patients who had no comorbidity except diabetes; furthermore, age ≥ 65 years was associated with a greater risk of death[4]. As described above, patients with hypertension and CVD were more likely to develop severe cases[4]. Furthermore, our analysis indicated that age, hypertension, CKD, and CVD were risk factors for COVID-19 mortality. Since the diabetes with comorbidities group had a higher prevalence of hypertension, CKD and CVD, there was no doubt that patients with diabetes with comorbidities had worse outcomes.

Comparing to the survivor of diabetic patients with COVID-19, the diabetic patients who died of COVID-19 had more severe inflammatory response, progressive organ injury, and also, undoubtedly, higher proportions of complications and severe cases.Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) Collaborative Group[19]and WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group[20] reported that systemic glucocorticoids was conducive to the reduction in mortality of COVID-19 severe cases. As the percentage of severe case in non-survivor group were 100%, while that rate in survivor group was just 33%, there was no doubt that non-survivor group had higher rate of using systemic glucocorticoids. Therefore,in such cases, higher rate of systemic glucocorticoids treatment in non-survivor group did not indicated higher rate of mortality in systemic glucocorticoids treatment.

One unanticipated result was that acarbose, not metformin, could improve prognosis through a decrease in the degree of inflammation, which was independent of the blood glucose level. In addition, acarbose accounted for 97% of the glycosidase inhibitors used. Fenget al[21] reported that acarbose could effectively block the metastasis of enterovirus 71 (EV71) from the intestine to the whole body. EV71 is one of the main causes of hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD), and its infection relies on the interaction of the canyon region of its virion surface and the glycosylation of the SCARB2 protein, which is the cellular receptor of EV71 infection. Danget al[22] found that acarbose not only inhibited cellular receptors of various glycosylated viruses but also competitively blocked the canyon region of the EV71 virion surface, blocking the metastasis of EV71 from the intestine. Angiotensin converting enzyme II (ACE2) is a SARS-CoV-2 cell entry receptor[23], and glycosylation sites play an important role in the combination of SARS-CoV-2 and its receptor[24,25]. Chloroquine was reported to block SARS-CoV-2 infection by interfering with the glycosylation of cellular receptors[26]. As previously stated, acarbose inhibited the glycosylation of EV71 receptors;additionally, patients with diabetes with COVID-19 who were treated with acarbose had better outcomes than patients who were not treated, suggesting that acarbose could improve the prognosis of COVID-19 infection by inhibiting the glycosylation of ACE2. In addition, compared to the non-acarbose group, the acarbose group had lower WBC, NLR, and CRP levels, indicating a decreased inflammatory response and further supporting the anti-SARS-CoV-2 function of acarbose. Furthermore, a previous study showed that acarbose could change the gut microbiota and then beneficially regulate the body’s immune function[27]. A recent study revealed that fetal microbiome changes occurred in patients with COVID-19, characterized by depletion of beneficial commensals and enrichment of opportunistic pathogens[28]. Therefore,we inferred that acarbose might increase the baseline abundance of microbiota that had inversely correlated with COVID-19.

As previous studies reported that metformin has multiple additional health benefits in patients with diabetes[29], we anticipated that metformin would improve prognosis after COVID-19 infection; however, the results were unexpected. Scanning the literature, we found that metformin improves ACE2 stability through AMPK[30],which means that metformin may increase ACE2 availability. In addition, the median level of FPG was higher in metformin users than in nonusers, as a previous study reported that improving glycemic control substantially reduced the risk of mortality from COVID-19.

The study has some limitations. First, due to the retrospective and multiple-center study design, some information, such as patients’ exposure history, the chronic disease severity and medication, diabetes medication, glycemic control and several laboratory items, was not available for all patients. There could be assay variability in different centers. Second, samples were only from Hubei Province, China; thus, more studies in other regions, even other countries, might obtain more comprehensive insight into COVID-19. However, this study is one of the largest retrospective and multicenter studies among patients with COVID-19. Additionally, this study is one of the first to investigate the influence of diabetes medications in patients with diabetes with COVID-19. The relatively abundant clinical data and numerous events also strengthen the results. The conclusion will help clinicians identify high-risk patients and choose suitable diabetes medication for patients with diabetes.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, patients with diabetes had worse outcomes when suffering from COVID-19; however, the outcome was not related to diabetes itself but to comorbidities such as hypertension, CKD and CVD. Furthermore, the administration of acarbose could reduce the risk of death, ARDS, and shock in patients with diabetes.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become an ongoing pandemic and has caused considerable mortality worldwide. Previous studies have demonstrated that patients with diabetes have a higher risk of mortality from COVID-19, as well as a greater risk of developing more severe cases.

Research motivation

Diabetes was a risk factor for the progression and prognosis of COVID-19, however,the effects of diabetes or anti-diabetic medication on the mortality of COVID-19 have not been well described.

Research objectives

We aim to investigate the outcome of different statuses (with or without comorbidity)and anti-diabetic medication use before admission of diabetic after COVID-19.

Research methods

The clinical characteristics of 1422 consecutive hospitalized patients were collected.The statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS (version 25.0).

Research results

The overall survival rate was significantly lower in the diabetes group (log-rankP<0.01), but the results for all-cause mortality were similar in the non-comorbidity group and diabetes only group (log-rankP= 0.59). Male sex [hazard ratio (HR) 2.59,P<0.001], hypertension (HR 1.75,P= 0.006), chronic kidney disease (CKD) (HR 4.55,P<0.001), cerebrovascular disease (CVD) (HR 2.35,P= 0.006), and age were independent risk factors for the COVID-19 mortality in multivariable Cox regression. However,diabetes alone was not an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with COVID-19.

Research conclusions

Although diabetes is associated with a higher risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19, the outcome was not related to diabetes itself. Age, hypertension, CKD and CVD were the independent risk factor of mortality.

Research perspectives

The present study calls more attention to the impact of older age and comorbid chronic disease, such as hypertension, CKD and CVD on disease progression among diabetic patients with COVID-19.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge all health-care workers involved in the diagnosis and treatment of patients in Hubei Province.

杂志排行

World Journal of Diabetes的其它文章

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, diabetes medications and blood pressure

- Utility of oral glucose tolerance test in predicting type 2 diabetes following gestational diabetes:Towards personalized care

- Diabetic kidney disease:Are the reported associations with singlenucleotide polymorphisms disease-specific?

- Metabolic and inflammatory functions of cannabinoid receptor type 1 are differentially modulated by adiponectin

- Medication adherence and quality of life among type-2 diabetes mellitus patients in India

- Galectin-3 possible involvement in antipsychotic-induced metabolic changes of schizophrenia:A minireview