“二战”前后日本造园教育回顾与展望

——以实践教育为例

2021-11-22沈悦

沈悦

0 引言

日本自1868年明治维新以来,积极融合西方文明并通过实施一系列教育政策来提高国民的文化素养,从而使之在亚洲率先发展为成熟型社会。风景园林在日本称为“造园”,日本造园教育在发展过程中,除传承传统文化外,还融合了世界的科学研究成果,体现出较高的应用水平,可为中国风景园林教育界提供值得参考的经验。本研究以日本造园教育为研究对象,通过回顾其起源与变化,结合与时代对应的社会发展及与造园相关的政策法规方面的变化,梳理造园教育的发展脉络,归纳其特征,以便为中国风景园林教育提供参考。研究方法主要是对文献的梳理和对文献作者及知情人的访谈。通过对资料的归纳总结,笔者认为应当反思当前“过分细化”型的专业教育体系,要以保持“高度综合性”为造园学科的基本特征,重视各领域知识的横向连接,更好地实现以“用”为最终目的的实践型教育。

1 起源与体系的建立——“二战”前的造园教育(1914—1945年)

1.1 造园教育的形成

日本的大学造园教育,始于1890年东京帝国大学(现东京大学)设立的农科大学林学科。1914年由本多静六教授①开设景园学课程,1915年农学科的原熙教授开设造园学课程。1916年,本多静六教授对林学学科的教育体系做了进一步整编,并开设了景园学总论课程,其学生田村刚开设东洋景园史课程,本乡高德博士开设西洋景园史课程,而后又有精于庭园研究的门生上原敬二加入了课程教学工作,构成了园林教育框架的雏形。1918年,田村刚对美国的“Landscape Architecture”研究领域进行了系统研究,出版了著作《造园概论》,确立了造园是一种关于“构成”的基础理论。1919年,经东京帝国大学林学与农学2个学科的教育者商议,把造园教育的科目统一定为“造园学”,作为2个学科的共同选修科目,由本多静六教授开设造园总论课程、原熙教授开设庭园论课程作为科目相关的课程。至此,初步形成了日本造园教育在大学层面的初始结构[1-2]。

1.2 造园学的专业背景

1919年以来,以东京帝国大学林学学科为中心开展的一系列造园教育的公开课程,吸引了大量社会听讲生。在如此高需求的驱动下,上原敬二先生联合各相关团体组织、召集造园教育相关人员,一同创立了庭园协会(日语:庭園協会),成为日本最初的造园团体组织。1928年,庭园协会设立了独立的设计部,当时日本国内较著名的建设项目都与协会的关键创始人员密切相关,如被称为史上第一个现代公园的日比谷公园即由本多静六教授设计。庭园协会还曾集中出版了《造园丛书》(全24卷),创办了杂志《造园》,在《造园》刊登的第一期中明确记录了庭园协会的会则,同时明确了“造园”的英译为“landscape architecture”而并非“garden”[3],这意味着造园虽然是一个新领域,却并不停留于庭园的小范围内。协会的创始人员具有多样的专业背景:如东京大学的本多静六教授不仅具有德国的经济学博士学位,还获日本的林学博士学位,在社会身份上,不仅是研究学者、教育家,还是投资者、园林设计者;此外,协会成员还有文学专业背景的龙居松之助、林学专业背景的田村刚和上原敬二;森林政策学专业背景的本乡高德博士;工学专业背景的大江新太郎博士等。由此可以看出,在造园学的始创阶段的构成人员专业背景是非常多样的,而且呈现出横向交流紧密且相辅相成的状态。同时造园学也随着国家的实际建设而得到了实践性的发展,因此可以说综合性和实践性是造园学的主要特征。

1.3 国家政策与造园教育的相互推动

在国家政策方面,日本在1837年时就有了太政官布达②政令,其申明要把全国的一些休闲地区、寺庙境域指定为公园。1888年政府又出台了《东京地区改造条例》,明确了城市改造建设时需要设置公园,成为公园设置的萌芽期。1919年第一次编制了《旧都市计划法》,其中对公园绿地的设置标准进行了明确的阐述,同年,造园学正式成为大学教育课程。1923年,日本突发关东大地震,由于公园绿地作为避难场所庇护了大量市民,使公园绿地在城市中的作用和存在意义得到了广泛的认可,也促使灾后重建时建成了数量众多的防灾公园。而后,在学者们的推动下,整个社会对于城市绿地的关注度逐渐提高,特别是以田园都市为蓝本的城市建造吸引了人们更多的关注。1932年东京绿地协议会成立后,对环东京地区50 km范围内的962 hm2土地做了总体规划,环城绿带系统的概念随之形成(“二战”后未能实现)。至此,可以说“二战”前的日本造园教育的基本特征是确立基本理论,教育出了一批务实工作的人才,这些人才对造园的普及、城建技术的开发、公共绿地的建设起到了重要的推动作用。在日本的城市绿地发展史上,这一时间节点也被称为综合性绿地规划的萌芽期[4]。这一时期形成的大部分国家政策理念都依托于大学及研究机构的学者,教育机构培育的人才在入职政府部门后也致力于将理论与实际相结合,并从内部推动政策的实施,体现了教育的意义所在。

2 社会意识与大学体系的完善——“二战”后的造园教育

2.1 城市绿地保护意识的提升促进造园教育发展

从社会背景来看,日本在战败后,城市公园由战争中的“防空绿地”被占用为临时建设材料堆放地,导致城市环境质量得不到改善,因此整个社会对恢复城市美观、确保公园基本功能的呼声日益高涨。为了保障城市中的绿地以及便于日后更有效地推进绿地建设,日本政府于1956年制定了《都市公园法》,确定了城市公园的建设、管理、维护体系。法律生效后,公园建设的预算逐年递增,促进了公园建设的快速发展。1957年,在国土层面上确立了《自然公园法》,在非城市层面指导了自然环境保护理念的开展,将国土中的重要资源按区域进行分级保护,为以后广域的自然空间保护树立了方向。这一时期,被称为公共绿地建设及理论确立的推动期。

1964年日本举办了东京奥运会,城市的基础建设延续了始于20世纪50年代后期的开发热潮,日本有凭借奥运会契机重新树立“二战”后国际形象的设想,但是由于建设的指导方针不当导致出现了很多形象工程,不可避免地产生了一些与传统空间相悖的建设,最终致使镰仓、京都、奈良等城市失去了一些至今也无法弥补的城市景观。经过反思,日本在1966年制定了《古都保存法》,确立了在文化景观保护层面上的规章制度。1966—1967年,接连出台了《首都圈近郊绿地保全法确立》《近畿圈郊区绿地保全法》,确立了以大城市为中心的广域范围的自然环境保护规制,对自然环境的保护起到了重要作用。这一时期可称为自然环境保护重点推动期。1972年出台了《自然环境保护法》,环境保护得到了公众的广泛认同;1973年出台了《都市绿地保全法》,旨在保护郊区绿地环境;此后,这2个保护法规共同指导城市内、外绿地的建设、保护及管理等事务,这一时期被称为城市化中的绿地广泛推动确保期[4]。在这一系列立法的背后都少不了教育行业及研究机构学者的参与推动,可以说“二战”后的造园教育发展与教育界学者们的社会活动紧密相连。

2.2 大学造园教育体系的完善

从大学教育上看,除“二战”前就有造园教育的东京大学(成立于1877年)、京都大学(成立于1896年)、北海道大学(成立于1918年),以及私立的东京农业大学(成立于1923,造园学科设立于1949年)继续为社会输送人才外,新成立的大学也统合了社会资源,开展了战后的造园教育事业。截至2021年,日本已有60余所大学开展了造园教育并设立于环境学(含农学)类、工学类、艺术类学科体系中。除了久负盛名的东京大学外,造园专业教育师资背景相对丰富的大学有:千叶大学(成立于1949年)、东京农业大学(成立于1923年,造园学科设立于1949年)③、大阪府立大学(原速浪大学,成立于1949年,农学部设立于1955年)、兵库县立大学(原姬路工业大学,成立于1949年)。其中千叶大学和东京农业大学的造园学科在被编入正式大学教育前还有很长一段中专、高专层级的教育历史,当时授课的教师有东京大学的田村刚、本乡高德、上原敬二等人[2]。上原敬二先生于1924年在东京农业大学成立了东京高等造园学校(现东京农业大学造园学科的前身)并担任校长。因此,在师资力量的加持下,这2所大学的造园教育起点较高。

3 日本造园教育的三段式特征

因大学教育要为社会需要输送人才,所以大学造园教育依据社会的发展,从最初侧重于小尺度项目(庭园、公园)的建设研究转变为后来对广域范围(城市、国土、地域环境)的研究。培养专业人才的重点也是从本科逐渐移到了“大学院”(即中国的研究生院)。东京大学、京都大学的教育注重“培育研究者”和“向国家中枢输送人才”,而其他大学一般致力于培养职业人才,人才的类型相对比较多样。以下分3个阶段阐述“二战”前后日本造园教育的特征。

3.1 以时间与空间为两大主轴的教育体系的发展阶段

日本造园教育以“时间”和“空间”为两大主轴,在造园学会层面上已有较多研究[5-6]。以时间为轴的教育模式主要体现为造园历史教育,除日本造园史(1868年以前)和世界造园史外,明治时代以后的近代造园史等的回顾与验证也是教育的重要一环。这种以时间为轴、以古今纵向发展的史学教育可称为纵向型教育,不仅可使学生认识过去,更重要的是能促使学生通过历史变迁总结规律,进而思索未来。比如兵库县立大学的绿地防灾教育就是以历史上不同阶段的事件,如1923年关东大地震、1995年的阪神淡路大地震,进行现象分析、推演城市中的开敞空间分布、人流避难路径、避难绿地的使用状态等,从而推导出未来的绿地存在方式。这种以时间为轴心的教育内容是造园实践教育活动中不可缺少的重要一环。

以空间为轴的教育则是以空间规划、空间设计为主要的展开方面。它的教育目的并非是把学生全部都培养为规划师、设计师,而是通过规划设计的学习过程使学生认识到专业上必须考虑的各种因素和推演方式,以及彼此之间的关系。它的教育模式属于横向型教育。对每个具体的地块(或地区)所涉及的地理环境、社区形态、法规、特有文化等进行横向结合,综合各项因素对研究区域做扎实的基础分析,进而思考、推演其未来的空间形式。

上述的“一横一纵”的主轴式教育组合呈现为“T”字形的教育模式(图1),空间轴上表示教育中应有的空间对象,有城市、交通设施、私邸、公园、河川、港湾,以及农地、山地等;而在纵向的时间轴上,除了主要的造园史外,还有自然史、文化史、设计史等其他专业背景的知识被纳入这个教育系统。这种模式的教育,对战后快速发展经济,满足社会刚性需求等方面起到了重要的作用。

1 发展阶段以两大主轴(时间和空间)为主的“T”字形教育“T”–shaped education content schematic (space and time)in the development stage

3.2 随时代变化的教育改良阶段

日本在战后公园绿地的政策上随社会状况变化做出了相应的改革。回溯日本关于绿地的主要立法和制度设置的变化,从《都市公园法》(1956年)到《都市绿地保全法》(1973年)的形成,以及“绿地总体规划纲要”的确立(1977年),总体而言,是将城市绿地的发展重点从中心城市推广至更广域的城市绿地保护和建设的过程。战争结束到20世纪80年代这一时期大学的造园教育更侧重于开发规划和空间设计,在校外的建设实践中也形成了各种各样的案例。1980年后,城市开发节奏进一步加快。1981年成立的“财团法人都市绿化基金”,标志着民有资源进入城市绿化领域[2],是官民共建绿色城市的里程碑。到20世纪90年代初,日本泡沫经济崩塌,城市建设规模缩减,民众的焦点重新聚焦于环境质量、开发前的环境评估等,这方面的项目委托数量增长。1995年阪神淡路大地震突发,地震中发生大规模火灾,造成6 434人死亡,住宅损毁639 686栋,这次自然灾害又一次警示了日本在城市中开敞空间的系统配置、城市防护隔离带规模、建筑及道路的安全基准上还存在着各种问题。在关西地区的家园重建中,重新思考人与自然的关系成了社会的关注点。

这一时期的教育虽然依旧普遍地承袭原有框架系统,但随着社会形势变化造园教育面临的课题也随之改变。1)需要把被忽略的绿地防灾避险功能重新放到重要的位置,加强防灾教育上的内容。2)加快规划设计手法的革新。20世纪80年代曾有一些日本设计师到欧美国家进修或短期留学,当其将日本当时的造园作品展示出时却未得到欧美学者的好评,反而被批评过于模仿欧美风格、未活用日本已有的造园资源,导致本土特色缺失。因此在当时看来,在教育层面上,如何引导学生对本国固有文化解读从而规划独具特色的风景还面临着较多的挑战。3)当时的社会发展已趋于成熟,公共空间的建设需要广泛的公众参与,即公共项目设计将由曾经的“由专家说了算”向“由使用者说了算”转变。从只重视“硬件”的建设过渡到“软件”与“硬件”的同时推进。因此,在广泛的公众参与体系中如何有效地把控、整合各类团体的诉求成为造园教育中一项重要内容。4)教学内容与实际工作脱节。作为实践性较强的造园学科经过长年发展,专业划分越来越细,而教师忙于完成科研任务和各种评审,参加工程实践的时间减少,导致了造园教育的内容上趋于培养学生的思考能力而忽视实践训练,且大部分学校是以毕业论文的形式作为毕业的最终条件,使得造园教育逐渐偏离了实践性教育。在这种状况下,对分工过细的各个专业重新梳理,为社会输送能够掌握实践技能人才成了一种需要。

为应对时代变化,1999年,在日本兵库县知事贝原俊民先生推动下,建立了一个能够应对时代教育需求的以景观园艺教学为主的学校。学校的教育内容由日本庭园协会全面监修,同时学校还召集了在新加坡、欧美等国家和地区中有长期造园工作经验的专家共同制订了一套理想的教育方案,以解决造园教学内容与实际工作脱节的现状。由于专家们最终确定的实践型课程的学时过多,在研究生院的教学内容配置上远远超出了当时文部省(相当于中国的教育部)的设置标准,因此在开校之初,暂时挂靠于姬路工业大学的自然环境科学研究所,首先开展研究生院层次的教育实践。学校名称为淡路景观园艺学校(日语:淡路景観園芸学校),校园建在震后修复的淡路岛,校园环境也是完全对应景观园艺教育而建。经过10年的不断更新运营后,被文部省认定为日本环境领域教育系统中唯一的实践型教育研究生院。学校的前几批学生几乎都来自名校,如东京大学、京都大学、筑波大学、千叶大学、神户大学、东京农业大学,以及加利福尼亚大学伯克利分校(University of California, Berkeley);生源的专业背景也多样,不仅有来自造园学、建筑学等专业的传统生源,还有来自三井物产、本田汽车等一流跨国企业的高管,更有造型艺术家、家政学教授、报社记者、海上保安厅技师等不同职业的学生,多样的价值观在学校里碰撞、交流后得出了很多新的发现。特别是非造园专业的学生所带来的观念和思考方式,为造园的创作注入了新的源泉,“造园的创作源泉在造园之外”的新思路在这所教育机构得到了实现。淡路景观园艺学校在2000年初始的教学内容涵盖了环境、栽培、建筑、土木(道桥)、艺术、城市设计、农村规划、传统造园、社区建设、人际关系、管理运营,以及大量的周边学④(应时势话题随时开课,表1)。课程有70%的是实习时间,1名教师平均只指导2名学生,实行少数精锐教育⑤。从概念上讲,是在传统的“T”字形教育模式的基础上将运营管理、政策施策的内容叠加上,形成“才”字形教育模式(图2)。

2 改良阶段的“才”字形教育概念图“才”–shaped educational schematic in the improvement stage

表1 1999年淡路景观园艺学校的课程内容Tab. 1 The Curriculum of the Awaji Landscape Planning and Horticulture Academy in 1999

“才”字形教育模式的重点是把管理运营内容融合到时间和空间轴层面,一方面是分析政府的行政策略并在教育中传授“诱导”政策取向的“技术”,让学生实际体验项目的立项过程和建设完成后的公共空间管理方法(图3)。另一方面是培养学生的“公众感”及沟通能力。日本除了国家重点项目以外,一般性造园建设项目必须有公众参与。来自不同地域的公众的参与度和需求表达方式也不同,如何在每一次深入公众时迅速地得到公众的信赖并形成良好的沟通关系,面对议论纷纷场面如何择善而行,最后如何使各方意见达成共识,并“诱导”它顺利地付诸到实施中等,这些“管控运营”手段都是教育的内容(图4)。而这些教育都是在教室之外的实际建设项目中实施完成的。这种现场型的实践教育可以使学生在较早的阶段拥有对就业发展的自信,在之后一系列跟踪验证中也证明了它有良好的效果。

3 学生在公园规划过程中听取管理方的意见(明石市)Students listening to the government’s opinions on park management during their park planning process (in Akashi City)

4 学生在公园规划过程中与公众沟通(淡路市)Students discussing with local residents during their park planning process (in Awaji City)

在与海外的交流上,淡路景观园艺学校除了设置外国专家来校教学制度,还设置了来自美国Fidelity财团赞助的园艺景观技术交换研修项目(triad program),学员通过在日、英、美三国轮流研修的方式,实现国际联合,将3个国家的造园技术的应用融会贯通。总之,自2000年开始,经过日本造园学会及建设行业对造园教育的反思,兵库县通过建立新校,率先进行了综合的尝试性教育并不断改进,使受教育者能够学以致用,让造园这一实践性较强的学科教育得到了以服务社会为实践方向的发展。

3.3 造园教育的成熟阶段

1)以空间为轴的教育。空间设计的实践教育着重于让学生在毕业之前实际参与造园建设的立项到设计、从监管到项目建成落地的全过程,而不是只停留在图纸评审的层面。整套教育流程包括从对实地的勘测、与甲方和公众沟通,到方案的比较、概算把控、建材选择,再至工程竣工的全过程参与(图5)。

5 实现从现场调查到项目竣工全过程的造园教学Education on a process of the landscape design from survey to completion

这里有空间设计的体验,也有设计过程中与公众沟通,与甲方沟通,策划实施汇报会的运营管控的实践。其中一个环节是学生在设计实习中与当地居民沟通,以学生作为主导者,来把握公园未来的使用人群、投资者、建设者、管理者等多方的诉求并与各方做出合理的沟通后,再将解决方案反映到图纸上,并不断在实际建设中与导师或建筑方沟通解决新发问题。大部分项目会在学生毕业前建成落地。对建成后的景观项目,学生还会对使用者进行满意度问卷调查、总结项目经验,在整套建设过程后,学生很容易将“空间设计”和“过程管控”的两方面技术的综合掌握并把它充实为自身的能力。学生在设计过程中,除了经历公众参与程序,还须经历与事业主体(政府)的沟通过程,这也对政府的项目推行建设起到了积极的作用。当建设主管部门(政府)与公众的意见不一致时,项目将无法推进。在此状态下,无利益关系的学生的参与意见就显得非常重要,而且研究证明,学生参与全过程也起到了政府(土地所有者)与公众(未来使用者)之间的润滑作用[7]。

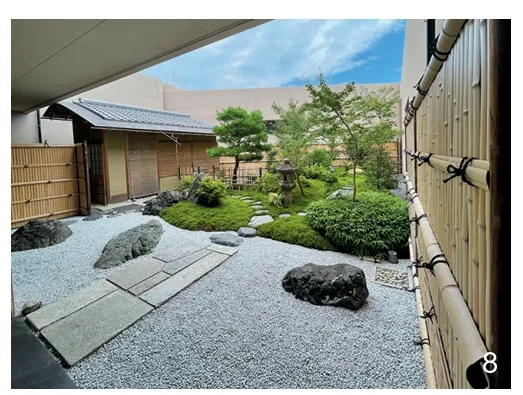

2)以时间为轴的教育。一方面是培养学生对于历史传统的认知;另一方面是培养学生对于因时间而变化的风景形成规律的认识。在历史传统方面的教育上,除了由资深的造园历史学家讲解历史外,主要集中于日本庭园的现场教育。通过现场实际操作感悟造园中画意的形成与四季变化的关系。在学习庭园建造时,首先强调亲身接触各种材料,体验传统材料的历史文化和加工工艺,然后才是做规划、施工,请京都一流的工匠手把手地指导制作细节(图6~8)。通过参与传统庭园建造的全过程,经历多次的现场试错与磨合,循序渐进地理解和把握传统美学的形成特征。在培养学生认识风景形成与时间变化上,除了进行线上的规划设计,还重点参与了现场建设。如尼崎市的尼崎21世纪之森就是一个通过设立时间轴来推进公园建设的项目,为保证公园的生态环境质量和防止外来植物入侵生态空间,公园内的绿化植物采用的都是从本地收集的植物种子,从育苗开始到长成良好的植物景观。公园的绿化建设时间长度规划为100年,在这个时间跨度下,每年让学生与当地居民共同参与公园的细节建设,包括采种育苗、移植树木,并在过程中对青少年开展环境教育。这些实践教育对培养学生形成风景的格局意识大有益处。学生通过参与项目建设会自然地意识到风景与时间、风土文化与时间之间的关系,促成自我价值的提升并与历史景观共同成长。

6 在京都学习传统的材料加工Students learning traditional material processing in Kyoto

7 在京都工匠的指导下进行庭园施工Traditional garden construction by students under the guidance of professional craftsmen in Kyoto

8 竣工后的日本传统庭园Completed traditional Japanese garden

3)管理运营的教育。一方面,需要加强政策制定手法、公众参与方面的教育。首先是研究政策制定,培养学生精通政策制定的各个环节,意识到专家在什么阶段该做什么。其次是培养学生掌握政策形成后对造园行业的“诱导”效果,掌握与上层决策者沟通的技巧让学生能够自如地在市长、部长乃至副知事面前在短时间内清晰表达自己的方案,并听取他们从宏观管理视角对方案提出的意见,提升学生自我的视野与洞察力(图9)。另一方面是教育学生要深入到城市住宅或乡间,掌握与居民沟通和挖掘场地潜能的能力,从现场发现问题再思考解决策略。这种类似“沟通学”的教育内容实际上是培养学生如何在特定环境下把握人际关系,并利用人际交往达成协作的目的,从而实现具体的规划目标。

9 在市领导前作方案说明A student presenting plans to city officials

兵库县立大学研究生院景观设计课程中,有关于农村聚落景观设计和建设的课题(图10),建设地点是淡路市摩耶聚落(Maya Village, Awaji City)。该村人口平均年龄达65岁以上,虽然人群普遍老龄化,但当地居民都精于躬耕并热情好客,对提升村落环境充满热情。师生们在深入村落进行实地调查后,归纳出了该村落的景观潜力,并和当地村民一同探讨了村落的风景建设构想和规划,以期实现乡村的振兴。学生的构想及规划得到了政府支持和来自多方的赞助,项目以“摩耶艺术村”为研究对象,把当地的风景资源整合提炼,设计了观景台、林中瑜伽台,通过间伐杂树,打开了通向海湾的最佳视线,打造出了当地的名景。建设用的木材是间伐树,遗留的树根被加工成地面上的艺术雕刻,整个过程中,学生与当地居民一起劳动,通过打造名景,促进了设计者及使用者之间的互动,提升了村庄的景观活力[8]。这种通过深入公众建立诚信,然后共同构想、规划、吸引资金等一连串的运营把控,不仅提高了学生自身的工作能力与自信,同时给老龄化地区的振兴带来了新的活力。

10 课程中的施工场景与完成的观景台Construction phase in the landscape design course and the completed observation deck

4)自然环境资源方面的体验型教育。除了常规性的生态教育外,尤其注重在实例中的体验式学习。如每一届学生都会参加一个兵库县丰冈市的“实现生态田园社会”的项目,该项目始于兵库县立大学对东方白鹳(Ciconia boyciana)的引种恢复和野生放养实验。兵库县的东方白鹳在湿地生态空间中原本处于食物链顶端的地位,在丰冈市因人类过量使用化肥造成湿地环境破坏而灭绝。2000年初,兵库县立大学将这种食肉鸟类从俄罗斯引种并人工饲养,进而实现了市内放飞并使之恢复成为野生鸟类。学生们通过“实现生态田园社会”项目,亲身体会到了每个自然物种、每一项自然资源在生态循环中的重要性,从而更深入地思考课堂上所学的理论(图11)。同时他们也通过这个项目的实习理解现代社会在资源整合方面的运营特征,从而具备了进入社会工作前的基本素养。

11 SDGs融入教育的一部分(通过校园放牧比较草地的人工管理)Education to tackle SDGs in campus (sheep control grass growth through herding sheep)

日本国会在2003年通过了《社会资本重点整备法》,此后公园绿地作为社会资本的一个重要组成部分被重点强调,提高了全社会对绿地价值的再认识。2008年又通过了《生物多样性基本法》,并以此为据建立了一系列更广泛的自然资源保全策略,进入了与环境共生的展开期。近年的教育领域,提倡将可持续发展目标(Sustainable Development Goals,SDGs)⑥融入教学。笔者预测将来会有更多的课程中增加SDGs内容,尤其是环境保护范畴,很容易融合在造园教育之中。兵库县立大学淡路校园在探索SDGs课程中的实践之一是通过放牧试验,测算校园中的草地管理,用以把握“减碳”和“资源循环”的可能性(图11)。这个项目还在实验取样过程中,从造园专业的角度来看,目标是既减碳又易于实施,且易于成景。

综上所述,2000年后的日本教育实践与探索都显示了环境资源在造园行业中的重要性,因此需要在教育系统的模式中增加相应的资源内容,如此可形成“米”字形的教育模式(图12)。它是以时间、空间、资源、管理这4个主轴支撑的实践教育系统,体现了造园教育应当拥有的高度综合性。在全球的环境问题越来越依赖于每个行业内的细节更新的时代背景下,“米”字形教育模式的资源轴在今后的发展中会不断地被放大,风景园林教育者应当有所准备。这也是从回顾历史过程中得出的未来展望。

3.4 小结

综上,“二战”后的日本造园教育发展有3个明显的阶段,第一阶段是基础框架的构筑(图1)。它继承了“二战”前的框架,是以造园建设中最基本的两大要素为轴心而展开的体系。在战后的复兴建设以及后来的经济高速发展的时代,这个体系对应了造园建设数量和人才培养数量上的需求。这时期的教育内容也是偏重实技,以本科教育为基本体系向社会输送人才。当经济发展减缓,产能过剩,人口增长停滞时,本科毕业生的就业方向逐渐多样化,高层次专业培养逐渐向转向研究生教育,形成了当今的教育结构。这个时期的造园建设已从追求数量而逐渐转向追求质量,注重将已建成的空间改造为更有效的使用空间。也是就形成了第二阶段的改良阶段(图2)。它把大学教育与实际需求脱节的部分重新整合,加强了以运营管理为重点的教育,以造园的“有效使用”为第一目的来审视以往的造园建设,并建立了可持续性发展的体系。第三阶段是近10年来环境问题与人类生存的关系已到了不能忽视的状态下,在对应气候变暖、维持世界生物多样性等战略上,需要落实到每一个具体的领域。对于社会经济的发展已经到达相对成熟阶段的国家而言,需要在实施有效的减碳措施并促进资源循环利用方面担当更多的义务和责任。作为面对实际的造园教育,以“米”字形的实践性教育模式展开,会使学生用更综合性的视野去面对未来的行业发展(图12)。

12 成熟阶段的“米”字形教育发展模式图“米”–shaped educational development model schematic in maturity stage

4 讨论与展望

通过回顾,明晰了造园教育应该是顺应时代需求而不断改良的综合性教育。在长年的衍变过程中专业领域被过分细化,教育过程偏重于“构想”“推理”而忽视“活用”,导致很多学生最后到毕业可能都无法完成一份正式的图纸,所以需要对教育不断改进。日本每隔几年就有学者对造园教育进行反思和讨论,热点话题都与造园的实用性相关。最近一次的内容是2019年对设计领域教育的反思[9],有的讨论参与者比较了美国公立大学以工作室为教学方式的课程密度,相比之下日本的同等教育内容明显不足;也有的参与者比较了国外大学造园教育的横向范畴,指出日本在同等教育的层次上因缺乏与外专业的横向互动而影响了专业的视野扩展和未来发展;更有人指出日本造园教育在策划和设计上的公众参与、交流共进不够注重,导致项目的“建”与竣工后的“用”脱节。特别是新冠肺炎疫情大范围地传播后,市内公园绿地成了为市民提供相对安全的消解压力的节点,从社会需求上讲必须重点研究使用与行为等关键点。长期以来,“人”与“自然”一直是世界风景园林领域的研究重点,展望将来,有必要加上在自然环境下的“人”与“人”的重点研究。如何处理好这三角关系,是今后成熟型社会环境下保证风景园林可持续性发展的又一关键。

通过回顾,我们再次意识到日本现代造园学科的教育的创始阶段,主要创建人物都有着丰富而多专业背景和各自的横向人脉。无论是奥姆斯特德还是本多静六,都有多专业的经历和学科统筹能力。在几个学科的边缘开拓出的高综合性的造园学科本不应该随着分工的细化而失去原有的“初心”(即高度综合性)。虽然在3D打印、人工智能技术不断发展的今天,人类对自然环境的分析能力和对社会的管控程度不断增强,但不能把技术手段当成目的。风景园林是追求人与自然和谐的大背景下实现人与自然共生的一个重要领域。因此,再一次强调为“用”而“建”,为“生存”而“保护”,为“行为”而“空间”,为“持续”而“管理”才是风景园林教育今后之路,也是实践型教育应当注重的关键点。

注释:

① 本多静六(1866—1952)是东京帝国大学教授,从事教育和科研的同时涉及大量的实务设计,被称为日本公园之父。退休后将全部财产捐赠于公益。

② “太政官布达”是指明治政府的太政官对各地发布的法令。

③ 东京农业大学成立于1923年,造园学科于1949年编入。

④ 周边学是可能与造园发生关系的外专业内容(如布展学,狩猎学等)。

⑤ “少数精锐教育”是指一名教师只教少数几个学生。对每个人单独辅导,精致地把握教育的全过程的教育方式。⑥ SDGs是联合国的可持续发展目标,2016年开始在全球范围内应用。

图表来源:

文中所有图表均由作者绘制和拍摄。

(编辑 / 李清清 刘昱霏)

A Review and Prospect of Landscape Education Before and After the World War Ⅱ: A Case Study of Practical Education in Japan

SHEN Yue

0 Introduction

Since the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Japan has actively integrated with the Western civilization and improved the cultural literacy of the people by implementing a series of educational policies,thus taking the lead in developing into a mature society in Asia. Chinese landscape architecture is known as “gardening” in Japan. Although it faces problems common in Asian countries, such as large population and crowded cities, Japan has integrated the world’s scientific research results in addition to inheriting traditional culture in the process of development, reflecting a high level of application.This provides valuable experience worthy of reference for the Chinese landscape architecture education development. This research takes Japanese landscape education as the object. By reviewing the origin and variety of landscape education in Japan, the social development state corresponding to the times, and the changes of policies and regulations related to landscape architecture, it sorts out the development process of landscape education and summarizes the characteristics, so as to provide reference for landscape architecture education in China. The research methods mainly comprise reviews of the literature and interviews with the literature authors and industry discipline.Through the summary of the data, I believe that we should reflect on the current “over-segmented”professional education system, maintain the “high integration” as the basic characteristics of the landscape architecture discipline, stress horizontal connection of knowledge in various fields, so as to better realize the practical education with“application” as the ultimate purpose.

1 Origin and System Establishment —Landscape Education Before the World War II (1914–1945)

1.1 The Formation of Landscape Education

Landscape education in Japan could be dated back to 1890 when the forestry discipline was established in the college of agriculture of the Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo).In 1914, Professor Seiroku Hongda①offered a Landscape Architecture (Japanese:景园学) course.In 1915, Professor Hiroshi Hara of the agricultural discipline gave the Landscape Architecture (Japanese:造园学) course. In 1916, Professor Seiroku Honda further reorganized the education system of the forestry discipline, and offered the course on the General Theory of Landscape Architecture. His student Takeshi Tamura opened the Japanese Landscape Architecture History course. Dr. Takanori Hongo offered the Western Landscape Architecture History course. Later, Keiji Uehara, a disciple skilled in researches, joined the course teaching work. They constituted the prototype of the landscape education framework. In 1918, Takeshi Tamura carried out systematic study of the “landscape architecture”researches of the United States, and publishedIntroduction to Landscape Architecture, which established landscape architecture as a fundamental theory of “composition”. In 1919, the educators of the forestry and agriculture disciplines of Tokyo Imperial University discussed and agreed to name the subject of landscape education as the “landscape architecture science”, and as a common selective course of the two disciplines. Professor Seiroku Honda offered General Theory of Landscape Architecture and Professor Hiroshi Hara gave the Landscape Architecture Theory as subject-related courses. By that time, the initial structure of Japanese landscape education at the university level was formed[1-2].

1.2 Professional Background of Landscape Architecture Science

Since 1919, the forest science discipline center of Tokyo Imperial University Forestry has launched a series of open landscape education courses,attracting a large number of students from the society. Driven by such a high demand, Keiji Uehara,together with relevant organizations and landscape architecture education personnel, founded the Landscape Architecture Association, which became the earliest landscape architecture organization in Japan. In 1928, a separate design department was set up in the Landscape Architecture Association. At that time, the most famous construction projects in Japan were closely related to the key founders of the association. For instance, Hibiya Park, known as the first modern park in the country, was designed by Professor Seiroku Honda. The association publishedLandscape Architecture Series(24 volumes) and founded theLandscape Architecturemagazine.The first issue of the magazine clearly recorded the rules of the Landscape Architecture Association,and stipulated the English translation as “landscape architecture” rather than “garden”[3]. This means that although landscape architecture was a new field, it was not confined to the small scale of gardens. The founders of the association had diverse professional backgrounds. For example, Professor Seiroku Honda of the Tokyo Imperial University had both a Ph.D. in economics from Germany and Doctor of Science in Forestry from Japan. In terms of social identity, they were not only research scholars and educators, but also investors and landscape designers. In addition,the association members included Matsunosuge Tatsui with literature background, Takeshi Tamura and Keiji Uehara with forestry background, Dr.Takanori Hongo with a professional background in forest policy, and Dr. Shintaro Oe with engineering background. It is apparent that the founders of the landscape architecture science had diverse professional backgrounds, presenting a state of close horizontal communication and inseparable interconnection. The landscape architecture science gained practical development along with the actual construction in the country. Therefore,comprehensiveness and practicality are virtually the main characteristics of landscape architecture science.

1.3 Mutual Promotion of National Policy and Landscape Education

In terms of national policy, Japan had promulgated the “Dajyokanfutatsu”②policy in 1837, which declared that some leisure areas and temple territories across the country should be designated as parks. In 1888, the government issued theRegulations on Reconstruction of the Tokyo Area, which stipulated that parks should be set up in urban reconstruction and construction.This was the embryonic period of park setting.In 1919, theOld Metropolis Planning Lawwas prepared for the first time, which clearly elaborated the setting standards for park green space. In the same year, the landscape architecture science was officially listed in the university curriculum. In 1923,the Great Kanoto Earthquake occured. Since the park green space as a refuge sheltered great many people, it was widely recognized for the role and existence significance in the city. This prompted the construction of numerous disaster prevention parks in the post-disaster reconstruction. Since then, under the promotion of scholars, the whole society paid more and more attention to urban green space. In particular, urban construction modeled on pastoral cities attracted higher attentions. After the establishment of the Tokyo Green Space Council in 1932, a master plan was made for the 962 hm2land within 50 km around the Tokyo area, and the concept of the green belt ring system was formed(it was not realized after the WWII). In short, the basic feature of Japanese landscape education before the WWII was to establish the basic theory and foster a group of practical talent, who played an important role in promoting the popularization of landscape architecture, the development of urban construction technologies, and the construction of public green space. In the history of urban green space development in Japan, this time node was also known as the embryonic period of comprehensive green space planning[4]. Most of the national policy principles formed in this period relied on university education and scholars at research institutions. After joining the government departments, the talents cultivated by educational institutions were committed to integrating theory with practice, and promote the implementation of policies from the inside, which reflects the significance of education.

2 Social Consciousness and Improvement of the University System— Landscape Education after the World War II

2.1 The Enhancement of Urban Green Space Protection Consciousness Promotes the Development of Landscape Education

From the perspective of social background,after Japan’s defeat in the WWII, urban parks were occupied from “air defense green space” in the war to temporary storage areas of construction materials.The quality of the urban environment could not be improved. Therefore, the whole society was increasingly demanding to restore the beauty of the cities and ensure the basic functions of the parks.In order to ensure the green space in the cities and promote more effective green space construction in the future, the Japanese government formulated theMetropolitan Park Lawin 1956, defining the construction, management and maintenance system of urban parks. After the law came into effect, the budget for park construction increased year by year, promoting the rapid development of park construction. In 1957, theNatural Park Lawwas established at the territory level, which guided the new development of the concept of natural environmental protection at the non-urban level,and carried out hierarchical protection of important resources in the land according to regions, setting up a direction for the protection of wide domains of the natural space in the future. This period is known as the promotion period for the construction of public green space and the establishment of theories.

In 1964, Japan hosted the Tokyo Olympics. The city’s infrastructure continued the development boom that began in the late 1950s. Japan wanted to take the opportunity of the Olympic Games to rebuild its international image after the WWII. However, due to the improper guidelines for construction, there emerged a lot of image projects, which inevitably led to the appearance of many constructions inconsistent with the traditional space, and made Kamakura,Kyoto, Nara and other cities lose some of unique the cityscapes that cannot be made up to now. After reflections across the country, Japan formulated theAncient Capital Preservation Lawin 1966, which established rules and regulations at the level of cultural landscape protection. From 1966 to 1967, it successively enacted theEstablishment of the Green Space Protection Lawin the Suburbs of the Capitaland theLaw on Green Space Protection in Kinki Circle Suburbs, which established wide-range natural environment protection regulations centered on big cities, and played an important role in the protection of natural environment. This period is known as the key promotion period of natural environmental protection. In 1972, theNatural Environmental Protection Lawwas introduced, and environmental protection was widely recognized by the public. In 1973, the Urban Green Space Protection Law was unveiled to protect the suburban green environment.Since then, these two protection laws have jointly guided the construction, protection and management of green space inside and outside cities. This period is known as the widespread promotion period of green space in urbanization[4]. Behind the series of legislation are the indispensable participation and promotion of scholars from the education circles and research institutions. In fact, the development of landscape education was closely linked to the social activities of scholars in the education circles after the WWII.

2.2 Improvement of Landscape Education System in Universities

From the perspective of university education,the Tokyo University (founded in 1877), Kyoto University (founded in 1896), Hokkaido University(founded in 1918), and the private Tokyo University of Agriculture (founded in 1923, with landscape architecture discipline established in 1949), which offered landscape architecture education before the WWII, continue to deliver talents to the society. The newly established university also integrated social resources to carry out the landscape education after the WWII. As of 2021, more than 60 universities in Japan had launched landscape education and put it in the environmental (including agronomy),engineering and art disciplines. In addition to the prestigious Tokyo University, there are a number of universities with a relatively rich faculty background of landscape education, including Chiba University(founded in 1949), Tokyo University of Agriculture(founded in 1923, with landscape architecture science discipline established in 1949)③, Osaka Prefecture University (formerly Naniwa University, founded in 1949, with the department of agriculture established in 1955), University of Hyogo (formerly Himeji University of Technology, founded in 1949). Among them, the Chiba University and Tokyo University of Agriculture had a long history of landscape education at the technical secondary school and college level before incorporating the landscape architecture discipline into formal university education. The lecturers included Takeshi Tamura, Takanori Hongo and Keiji Uehara from Tokyo University[2]. In 1924,Keiji Uehara founded the Tokyo Higher Landscape School of Tokyo University of Agriculture (the predecessor of the landscape architecture discipline of Tokyo University of Agriculture) and served as the principal. Therefore, with the support of mighty faculty, the two universities had a high starting point in landscape education.

3 Three-Stage Characterized Japanese Landscape Education

Since university education should provide talents to meet the needs of the society, university landscape education has conformed to social development, shifting priority from the initial focus on the construction research of small-scale projects(gardens and parks) to the present research of wider ranges (urban, land and regional environments).The emphasis of professional talent cultivation has also gradually moved from undergraduate courses to graduate schools. Education at Tokyo University and Kyoto University stresses “fostering researchers” and “delivering talents to national key departments”, while other universities are largely committed to cultivating professional talents, with relatively diverse majors. The three stages illustrate the characteristics of Japanese landscape education before and after the WWII.

3.1 The Development Stage of Landscape Education System with Time and Space as Main Axes

The Japanese landscape education takes “time”and “space” as the main axes, and there have been many researches at the landscape architecture society level[5-6]. The time-based education model is mainly embodied in the landscape history education. In addition to the Japanese landscape history (before 1868) and the world landscape history, the review and verification of the modern landscape history after the Meiji Restoration is also an important link of education. Such a history education with time as the axis on the vertical development in ancient and modern times is referred to as the vertical education. It makes students understand the past and, more importantly, promotes them to summarize the rules through historical changes,and think about the future. For example, the green space disaster prevention education of University of Hyogo cites events at various stages of history,such as the Kanto earthquake in 1923 and the Hanshin-Awaji-daishinsai earthquake in 1995, to perform phenomenon analysis, and deduce open space distribution, evacuation paths for the people,and the state of the use of refuge green space in cities, so as to derive the future existence modes of the green space. Such a time-centered education content is an indispensable part of the landscape practice education activities.

Education with space as the axis is mainly based on spatial planning and spatial design. The educational purpose is not to train all the students into planners and designers, but through the learning process of planning and design to make students realize the various professional factors and inference modes that must be considered, and their relationship. Such an education model belongs to the horizontal education. The geographical environment,community form, regulations and unique culture involved in each specific plot (or region) are integrated horizontally to make a solid basic analysis of the research areas based on various factors, and further think and deduce the future spatial form.

The above horizontal and vertical axis-based education portfolio is presented as a T-shaped educational model (Fig. 1). The space axis represents the due space objects in education, including cities, transport facilities, private residences, parks,rivers, harbors, farmlands and mountains. In the longitudinal timeline, in addition to the main garden history, there are other professional background knowledge of natural history, cultural history, design history and so on is included in the education system. In the vertical timeline, in addition to the main landscape history, other professional background knowledge, such as natural history,cultural history and design history, are included into the education system. This model of education has played an important role in boosting the economy to meet the rigid demand of the society after the war.

3.2 Improvement Stage of Landscape Education Along with Times

Japan made corresponding reforms in the postwar park green space policy along with the changes in social conditions. Looking back upon the changes in the main legislation and systems of green space in Japan, we can see that from the formation of theMetropolitan Park Law(1956) to theUrban Green Space Preservation Law(1973) and the establishment of the Outline of Green Space Master Plan (1977), Japan promoted the development focus of urban green space from central cities to the protection and construction of urban green space in a wider range. The university landscape education from the end of the war to the 1980s focused more on the development planning and spatial design,and a variety of cases were formed in off-campus construction practice. After 1980, the pace of urban development was further accelerated. In 1981, the“Consortium Legal Person Urban Greening Fund”was established, marking that private resources entered the field of urban greening[2]. It was a milestone in the co-building of green cities by the government and the people. By the early 1990s,Japan’s bubble economy collapsed. The urban construction was scaled down, and the focus of the people was redirected to environmental quality and pre-development environmental assessment.The number of commissioned projects increased.In 1995, the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake broke out with massive fires, killing 6,434 people and damaging 639,686 houses. This natural disaster once again warned Japan of various problems in the system configuration of open space in cities,the scale of urban protection and isolation zones,and the safety benchmarks of buildings and roads.In the reconstruction of homes in the Kansai area,rethinking the relationship between man and nature became the focus of the society.

Although education in this period remained generally inheriting the original framework system,the topics of landscape education also altered along with the changes of the social situation. 1) The neglected disaster prevention function of greenspace should be put back to an important position to strengthen the content of disaster prevention education. 2) Accelerating the innovation of planning and design methods. In the 1980s, some Japanese landscape designers went to Europe and America for advanced studies. When they showcased the Japanese landscape architecture works of that time, they were not well received by European and American scholars, but were criticized for excessive imitation of the European and American styles, failing to make flexible use of the existing Japanese landscape resources, which led to the lack of local characteristics. Therefore, it seemed at that time, at the educational level, how to guide students to interpret the native culture and thus plan unique scenery was still facing many challenges. 3) At that time, the social development tended to be mature, and the construction of public space required extensive public participation. That is to say, the public project design would change from the former pattern of “experts having the final say” to the one “decided by the users”. It would also transition from only stressing “hardware” in the construction to the simultaneous promotion of both “software” and “hardware”. Therefore, how to effectively control and integrate the demands of various groups in the wide public participation system became an important part of the landscape education. 4) The teaching content was out of touch with the actual work. After years of development,the landscape architecture discipline of strong practicality was getting more and more segmented in the professional division. However, the teachers who were busy completing scientific research obligations and various reviews, gave less time to participate in engineering practice. As a result, the content of landscape education tended to cultivate students’ thinking ability and ignore practical training. Moreover, most schools took graduation papers as the final condition for graduation, making landscape education gradually deviate from practical education. In this situation, it has become necessary to re-scrutinize the excessively segmented division,and deliver talents who master practical skills to the society.

In response to the change of the times, a school based on landscape planning and horticulture education was established in 1999, under the impetus of Mr. Toshitami Kaihara, governor of the Hyogo County. The educational content of the school was fully supervised by the Japanese Landscape Architecture Association. The school also gathered experts with long-term landscape architecture experience in Singapore, Europe and the United States to jointly formulate an ideal educational plan to solve the disconnection of the teaching content of landscape from the actual work.Since the experts finalized excessive hours of the practice course, far exceeding the setting standard of the Ministry of Education at that time in the graduate school teaching content configuration,it was temporarily attached to the Institute of Natural Environment Science of Himeji University of Technology at the beginning of the school,and first launched the practical education at the graduate school level. The school, named as Awaji Landscape Planning and Horticulture Academy,was built in the Awaji Island, which was resurrected after the earthquake. The campus environment was completely to conform to the landscape architecture and horticulture education. After 10 years of continuous renewal and operation, it was recognized by Ministry of Education as the only graduate school of practice-based education in Japan’s environmental field education system.The first groups of students of the school almost all came from prestigious universities, such as the Tokyo University, Kyoto University, University of Tsukuba, Chiba University, Kobe University, Tokyo University of Agriculture, and the University of California, Berkeley. The professional backgrounds of students were also diverse. They were students from the traditional disciplines of landscape architecture science and architecture, or executives from first-class multinational enterprises such as Mitsui Products and Honda Automobile, or from diversified professions such as modeling artists, home economics professors, newspaper journalists and marine security agency technicians.A lot of new discoveries were made after the collision and communication of various values in the school. In particular, the ideas and ways of thinking brought by non-landscape architecture major students injected new sources into the landscape architecture creation. The new idea that“the source of landscape architecture creation is outside the landscape architecture” was realized in this educational organ. The teaching content of Awaji Landscape Planning and Horticulture Academy in early 2000 covered the environment,cultivation, architecture, civil engineering (road and bridge), art, urban design, rural planning, traditional garden, community building, human relationships,management operations, and a large amount of peripheral sciences④(courses were offered at any time to meet current events of trends, Tab. 1).About 70% of the course time were applied for internship. One teacher guided only two students on average to implement elite education⑤.Conceptually, it is to superimpose the content of operation management and policy measures on the traditional “T”-shaped education model to form the “才”-shaped education model (Fig. 2).

The focus of “才”-shaped education model is to integrate the management and operation content into the time and spatial axes. On the one hand,it is to analyze the government’s administrative strategy and imparts the “technology” to “induce”the policy orientation in education, so that students can actually experience the process of project approval and the public space management method after the completion of the construction (Fig. 3).On the other hand, it is to cultivate students’ “public sense” and communication ability. In Japan, except for national key projects, public participation in the workshop is a must for general landscape architecture project construction. Participants from different regions are involved and express demands in different ways. The “operation control”measures, such as how to quickly win the trust of the public and form a good communication relationship when going deep into the public, how to choose the good in the face of controversy, how to make the opinions of all parties a consensus, and put it into smooth implementation, are the content of education. All these education are completed in the actual construction projects outside the classroom (Fig. 4). This on-site practical education can give students confidence in employment development at earlier stages. It has also proven good results in a subsequent series of tracking validations.

In terms of overseas communication, in addition to setting up the system of inviting foreign experts to teach in the school, Awaji Landscape Planning and Horticulture Academy also established the triad program, sponsored by the US Fidelity consortium, for the exchange studies of horticultural landscape technologies. By allowing students to take turns to study in Japan, Britain and the United States, it achieves international unity, and integrates the landscape architecture application technologies of the three countries.In short, since 2000, the Japanese Landscape Architecture Association and the construction industry have reflected on the landscape education.Hyogo County, by establishing a new school,took the lead in implementing comprehensive experimental education and making continuous improvement, so that the learners could apply what they have learned, and lanscape architecture, a practical discipline education, could develop in the way of serving the society.

3.3 The Mature Stage of Landscape Education

1) Education on the space axis. The practical education of space design focuses on allowing students to actually participate in the full landscaping process from project approval to design, from supervision to project completion,before graduation, rather than only staying at the level of drawing review. The whole educational process includes the participation from the survey on the field, communication with Party A and the public, to the comparison of the plan, control of the budget, selection of building materials, to the completion of the project (Fig. 5).

There are experiences of space design,and the practice of operation control, such as communicating with the public in the design process, communicating with Party A, and planning and implementing the briefing meeting. One link is that students communicate with the local residents during their design internship. The students serve as the leader to grasp the demands of the future users, investors, builders and managers of the park, make reasonable communications with all parties, then reflect the solutions on the drawings,and constantly communicate with the mentor or construction side to solve the new problems found in actual construction. Most projects will be completed before the students graduate. For the completed landscape projects, the students will conduct user satisfaction questionnaires and summarize the project experience. After the whole construction process, it is easy for the students to comprehensively master the two aspects of“space design” and “process control” technology and enrich it into their own ability. In the design process, in addition to going through the public participation process, students must also experience the process of communicating with the business subject (the government), which also plays a positive role in the implementation of project construction by the government. When the construction authorities (government) disagree with the public,the project will not be advanced. In this state, it is very important for students with no stakes to participate in the process. Studies have shown that student participation in the whole process could lubricate the relationship between the government(landowner) and the public (future users)[7].

2) Education on the time axis. On the one hand, it is to cultivate students’ cognition of historical tradition. On the other hand, it is to cultivate students’ understanding of the laws of landscape formation that changes due to time changes. In terms of historical tradition education,in addition to explaining history by senior landscape historians, it mainly focuses on onsite education in Japanese gardens. For example,through pruning garden plants, students can grasp the subtle relationship between plant growth and spatial changes. Through the actual operation on site, students can perceive the relationship between the formation of artistic inspiration in landscape architecture and the changes of the four seasons.When learning landscape architecture construction,students are first told to personally touch materials with their fingers, and experience the history, culture and processing technology of traditional materials.Then it comes to planning and construction. Top craftsmen of Kyoto are invited to guide, hand in hand, the production details (Fig. 6-8). By participating in the whole process of traditional garden construction, students will experience many field trials and run-in, and understand and grasp the formation characteristics of traditional aesthetics step by step. In cultivating students to understand the formation of landscape and time changes, it is essential to allow them participate in the on-site construction, in addition to online planning and design. For example, the 21st Century Forest in the city of Amagasaki is a project to advance the construction of the park by establishing a timeline.To ensure the ecological environment quality of the park and prevent exotic plants from invading the ecological space, the greening plants in the park are fostered with seeds collected locally. From seedling to growing into a good plant landscape, the timeline for the greening construction of the park is planned for 100 years. In this time span, students and local residents participate in the details of the park construction every year, including collecting seeds for the culture of seedling, transplanting trees, and providing environmental education for teenagers in the process. Such a practice education has great benefits to cultivating students to form the pattern consciousness of landscape. By participating in the project construction, students will naturally realize the relationship between scenery and time,local culture and time, improve self-value and grow together with the historical scenery.

3) Education for managing operations. On the one hand, it is necessary to strengthen the education in “policy-making techniques” and“public participation”. The first is to study policy formulation, train students to be proficient in all aspects of policy formulation, and realize what the experts should do in each stage. The second is to cultivate students to master the induction effect of policy formation on the landscape architecture industry, command the skills for communicating with upper decision makers, so that they could freely express their plans in front of the mayor,department director and even deputy governor in a short time, listen to their opinions on the plan from the perspective of macro management, and improve students’ self-vision and insight (Fig. 9).On the other hand, it is to encourage the students to go deep into urban housing or countryside,master the ability to communicate with the residents and tap the potential of the site, find problems at the site and think about solution strategies. Such a“communication” educational content is actually to train students how to grasp human relationships in specific environments and use interpersonal communications to achieve the collaborative goals and hence fulfill specific planning goals.

In the landscape design course of the Graduate School of University of Hyogo, there is a topic on the landscape design and construction of rural settlements (Fig. 10). The construction site is Maya Village, Awaji City. The average age of the villagers is over 65 years old. Although the population is generally aging, the local residents are skilled in farming and hospitable to visitors. They are full of enthusiasm for improving the village environment. After conducting a field investigation into the village, the teachers and students summed up the landscape potential of the village, and discussed the landscape construction concept and planning of the village with the villagers, in order to achieve the revitalization of the countryside. The students’ conception and planning won support of the government and received sponsorship from various parties. The project takes “Maya Art Village”as the research object, integrates and refines the local landscape resources, and designs the viewing platform and forest yoga platform. By cutting the miscellaneous trees at intervals, it opens up the best sight to the bay and creates a famous scenery in the locality. The timber used for construction was from the chopped miscellaneous trees. The roots left on the ground were processed into artistic carving works. During the whole process, the students worked together with the local residents. By creating famous scenery, it promoted the interaction between the designers and users, and enhanced the landscape vitality of the village[8]. This series of operational control, such as building integrity in the public and then jointly imagining, planning and attracting funds, not only improved students’ working ability and confidence, but also brought new vitality to the revitalization of the aging areas.

4) Experience education in natural environmental resources. In addition to conventional ecological education, priority should be given to experiential learning in examples. For example, every class will participate in a project of “Realizing the Ecological Pastoral Society” in Toyooka City, Hyogo County,which began with the introduction for the restoration of the oriental white stork (Ciconia boyciana) and wild stocking experiments by University of Hyogo.The oriental white stork in Hyogo County was originally at the top of the food chain in the wetland ecological space. It became extinct in Toyooka City due to the wetland environmental damage caused by excessive human use of chemical fertilizer. In early 2000, Hyogo County University introduced the carnivorous bird from Russia and raised it artificially.In turn, the birds were released in the city and restored to wild status. Through the “Realizing the Ecological Pastoral Society” project, the students personally realized the importance of each natural species and each natural resource in the ecological cycle, thinking more deeply about the theories learned in the classroom. They also understood the operation characteristics of the modern society in resource integration through the internship of this project, and had the basic quality before entering the social work.

In 2003, the Japanese parliament passed theKey Social Capital Preparation Law. Since then, park green space has been highlighted as an important part of social capital, which helps to improve the re-understanding of the value of green space in the whole society. In 2008, theBasic Law of Biodiversitywas adopted, and a series of broader natural resources preservation strategies were established on this basis, marking the country has entered the development period of symbiosis with the environment. Recent years, the sustainable development goals (SDGs)⑥are integrated into education and are advocated. It is estimated that more courses will incorporate the SDGs content in the future, especially the category of environmental protection will be easily integrated in landscape education. One of the practices of the Awaji campus of University of Hyogo in SDGs exploration courses is to measure the grassland management on campus through grazing experiments to grasp the possibility of “carbon reduction” and “resources cycle”(Fig. 11). This project is still in the experimental sampling process. From the perspective of landscape architecture expertise, the goal is to reduce carbon and make it easy to implement and make scenes.

To conclude, the Japanese educational practice and exploration after 2000 have shown the importance of environmental resources in the landscape industry. Therefore, it is necessary to add corresponding resource content to the model of the education system, so as to form the“米”–shaped education model (Fig. 12). It is a practical education system supported by the four main axes of time, space, resources and management,reflecting the highly comprehensive nature that landscape education should have. In the context that the global environmental problems are becoming more and more dependent on the updated details in each industry, the resource axis of the “米”–shaped education model will be continuously amplified in the future development, and landscape architecture educators should be prepared. This is our future outlook derived from the review of history.

3.4 Summary

It can be concluded that there are three obvious stages in the development of landscape education in Japan after the WWII. The first stage was the construction of the basic framework(Fig. 1). It inherited the framework before the WWII, and was a system centered on the two most basic elements of landscape construction. In the era of post-war revival construction and the later era of rapid economic development, this system corresponded to the “quantity” of landscape construction and the quantity of talent cultivation.In this period, the educational content focused on practical technology, with undergraduate education as the basic system to deliver talents to the society.As economic development slowed down, with excess production capacity and stagnated population growth,the employment direction of the undergraduate was gradually diversified, and high-level professional training was bit by bit shifted to graduate education,forming today’s education structure. In this period,the landscape construction gradually shifted from quantity to quality, paying attention to forming the built space into more effective use space. This led to the improvement stage in the second stage (Fig. 2). It re-integrated the disconnected university education from the actual needs, strengthened education with focus on operation and management, examined the previous landscape construction for the first purpose of the effective use of parks and green spaces, and established a system of sustainable development.In the third stage, the relationship between the environment and human survival in the past 10 years has reached a state that cannot be ignored. The strategies of tackling climate warming and maintaining biodiversity need to be implemented in every specific field. To realize effective carbon reduction measures and achieve the recycling of resources, countries with mature economic and social development need to assume more obligations. The landscape education proceeds with the “米”-shaped practice-based education mode, which will make students have a more comprehensive vision to deal with the future profession development (Fig. 12).

4 Discussion and Prospect

Through the reviews, it has become clear that landscape education should be a comprehensive education that is constantly improving in line with the needs of the times. It is over-segmented in the professional field in the years of evolution. The education process emphasized “conception” and“reasoning”, while ignoring “flexible application”. As a result, many students may not be able to complete a formal drawing upon graduation. So there needs continuous improvement in education. Every few years in Japan, scholars would reflect on and discuss landscape education, and the hot topics are related to the practicality of landscape architecture. The latest event was a reflection on education in the design area in 2019[9]. Some participants compared the curriculum density of studio-based teaching method in public universities in the United States. In contrast,Japan’s equivalent education is clearly inadequate.Other participants compared the horizontal category of landscape education in Japanese and foreign universities, concluding that the lack of horizontal interactions with foreign majors at the same level of education has affected the expansion of vision and future development of the major. And some pointed out that public participation and communication in Japanese landscape education received insufficient attention, leading to disconnection of project“construction” and the “use” after completion. In particular, after the wide spread of the COVID-19 epidemic, urban green park space has become a relatively safe node for the people to relieve pressure.In terms of social needs, we must pay high attention to studying the key points of use and behaviors.For a long time, “man” and “nature” have been the research focus in the field of modern landscape architecture. Looking forward, it is necessary to add the relations of “man” and “man” in the natural environment in the key research list. How to deal with this triangle relationship is another key to maintain sustainable landscape architecture under the mature social environment in the future.

Through the reviews, we have once again realized that in the founding stage of modern landscape architecture, the main characters all had rich and multiple professional backgrounds and their own horizontal connections. Both Olmsted and Seiroku Honda had multiple professional experiences and discipline coordination ability.The highly comprehensive landscape architecture discipline that is developed on the edges of several disciplines should not lose its “original aspiration”(i.e., highly comprehensive) with the detailed division. Although today 3D printing and artificial intelligence technology are advancing continuously,and the human ability to analyze the natural environment and control the society is constantly enhanced, the technical means cannot be taken as the purpose. Landscape architecture is an important field to realize the symbiosis between man and nature under the background of pursuing the harmony between man and nature. Therefore, we should once again emphasize that “construction”for “use”, “protection” for “survival”, “space” for“behavior”, and “management” for “continuity”are the path of landscape education in the future.They are also the key in practice-based education.

Notes:

① Seiroku Honda(1866–1952) was a professor at Tokyo Imperial University. He was engaged in education and scientific researches, while involved in a large number of practical designs, hence known as the father of Japanese parks. After retirement, he donated all his properties to the public welfare.

② “Dajyokanfutatsu” referred to the decrees issued by the officer to all regions during the Meiji regime.

③ Tokyo Agricultural University was founded in 1923, and the landscape architecture discipline was incorporated in 1949.

④ The peripheral science refers to the content of other disciplines that may be related to landscape architecture(such as exhibition and hunting).

⑤ “Dedicated few elite education” refers to an education mode in which a teacher teaches only a few students,tutors each person alone, and has exquisite grasp of the whole process of education.

⑥ SDGs are the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which were applied globally in 2016.

Sources of Figures and Table:

All figures and table are provided by author.

(Editors / LI Qingqing, LIU Yufei)