Favipiravir and its potentials in COVID-19 pandemic: An update

2021-11-19DaoNgocHienTamAhmadQarawiMaiNgocLuuMorganTurnageLinhTranGehadMohamedTawfikLeHuuNhatMinhNguyenTienHuyTatsuoIiyamaKyoshiKitaKenjiHirayama

Dao Ngoc Hien Tam, Ahmad T Qarawi, Mai Ngoc Luu, Morgan Turnage, Linh Tran, Gehad Mohamed Tawfik, Le Huu Nhat Minh, Nguyen Tien Huy, Tatsuo Iiyama, Kyoshi Kita, Kenji Hirayama

1Online Research Club, School of Tropical Medicine and Global Health, Nagasaki University, Nagasaki 852-8523, Japan

2Asia Shine Trading & Service CO. LTD., Ho Chi Minh City 700000, Vietnam

3Essen Healthcare, Bronx, New York 10461 USA

4Department of Internal Medicine, University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City 700000, Vietnam

5American University of the Caribbean, Cupecoy, Sint Maarten

6Institute of Fundamental and Applied Sciences, Duy Tan University, Ho Chi Minh City 700000, Vietnam

7Faculty of Natural Sciences, Duy Tan University, Da Nang City 550000, Vietnam

8Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt

9Methodist Hospital, Merrillville, Indiana, United States

10School of Tropical Medicine and Global Health, Nagasaki University, 1-12-4 Sakamoto, Nagasaki 852-8523, Japan

11Department of International Trials, Center of Clinical Sciences, National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM), Tokyo, Japan

ABSTRACT

KEYWORDS: Favipiravir; Avigan; COVID-19; SARS-CoV-2;Antiviral; Review; Efficacy

1. Introduction

Over a year ago, the world started fighting coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). No country was left unscathed. This new virus has unleashed a global crisis that we are still facing today. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) report, on August 10th,2021, there have been 203295170 confirmed cases and 4303515 confirmed deaths worldwide. Maximum resources must be spent to fight the virus and its new strains, although each country has its own difficulties. The healthcare system bears a huge responsibility caused by the COVID-19 pandemic because of its transmission dynamics and polyphasic nature[1]. Therapeutic strategies such as antiviral drugs are essential to cope with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2)[2]. When SARS-CoV-2 emerged, contact tracing and physical distancing began while trials for vaccines and therapeutic drugs were launched in many countries,including Japan. One of the most efficient approaches to discovering effective drugs is to test the efficacy of existing antiviral medications in treating related viral infections, and favipiravir (Avigan) seemed to be a potential candidate. Favipiravir is a synthetic prodrug, which acts as a competitive inhibitor of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase,thereby preventing the replication of RNA by negatively acting on genetic copying. It was first discovered while assessing the antiviral activity of chemical agents active against the influenza virus in the chemical library of Toyama Chemical Co., Ltd and was initially approved in Japan for the management of influenza infections in 2014. Favipiravir has activity against other RNA viruses such as the Ebola virus, Lassa virus, and a broad range of influenza viruses,including influenza A and B, A (H1N1) pdm09, A (H5N1), and A(H7N9) avian virus, as well as oseltamivir- and zanamivir-resistant influenza viruses, several agents of viral hemorrhagic fever and now SARS-CoV-2 in vitro[3,4]. Favipiravir was approved and used in many countries including Bangladesh, China, Egypt, France, India,Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey,Ukraine, the United Arab Emirates, and Uzbekistan for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2[5]. Many countries started using it as a potential treatment for COVID-19[6]. Although it is approved for use in such an urgent situation, large scale trials are necessary to evaluate its place in the further management of COVID-19. Eighty-five percent of COVID-19 patients have mild to moderate disease, which can be treated at home; consequently, this drug could benefit a considerable number of patients. Favipiravir dosing is either a loading dose of 1800 mg in adults followed by 800 mg twice daily, or a 1600 mg loading dose followed by 600 mg twice daily, up to 14 days[5,7].However, favipiravir cannot be administered to expectant mothers or those who may become pregnant due to its teratogenic effects. The benefits of antiviral medicines in the prevention of illness spreading on local outbreaks are yet to be revealed. Lastly, the practical efficacy of such an intervention regimen will depend on its dose,treatment duration, and cost as well as difficulties in application.

In this review, we overview the initial and current usage of favipiravir, its regulations for COVID-19 management in the world,current evidence of its safety and efficacy, as well as its mechanism of action against the virus.

2. Origin of favipiravir usage and countries currently approved or considered favipiravir in the treatment of COVID-19

In 2014, favipiravir was approved in Japan by the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) to treat novel or re-emerging influenza virus in cases where other antiviral agents were inactive or not efficient[8]. The initial dosage in adults is 1600 mg twice a day,followed by 600 mg twice a day during five days of treatment.

At present, favipiravir is approved to treat COVID-19 in India,Indonesia, Russia, Malaysia, and China[9-13]. In India, favipiravir is intended to treat mild-to-moderate COVID-19 patients with the initial dosage of favipiravir 1800 mg twice a day, followed by 800 mg twice a day for 14 days[9]. The manufacturer of favipiravir,Fujifilm Toyama Chemical Co. filed a registration for the approval of this drug in Japan in October 2020 with the hope of getting the license in December 2020[14]. However, the effectiveness of favipiravir could not be confirmed by clinical evidence and awaited additional data such as clinical trial results from the U.S.[15,16].According to the agency, clinicians in these studies were not blinded leading to a high risk of bias, making the results inconclusive[14].Approval of favipiravir was pending additional clinical studies involving 270 patients in February 2021[17].

Till March 2021, 37 clinical trials were investigated for the efficacy or safety of favipiravir on clinicaltrials.gov (Supplementary Table 1).The studies are conducted in several countries over the world including the U.S., the U.K., the Russian Federation, Canada, Egypt,Kuwait, China, Romani, Germany, Iran, Indonesia, Italy, Saudi Arabia, Mexico, Bangladesh, Bahrain, Hungary, Nepal, Thailand,Turkey, South Africa, and Kazakhstan.

Table 1. Efficacy of favipiravir against SAR-CoV-2 in randomized clinical trials.

3. Pre-clinical trials evidence against SAR-CoV-2 and other virus species

The in vitro data of favipiravir against SAR-CoV-2 are limited,as only one study showed that the half-maximal effective concentration (EC) of favipiravir against nCoV-2019 BetaCoV/Wuhan/WIV04/2019 infected in Vero E6 cells was 61.88 μM[18].Although this value was more promising than the results of other nucleoside analogs such as ribavirin and penciclovir, the value was still much higher than remdesivir which is an approved drug for COVID-19 treatment[18]. Interestingly, a derivative of favipiravir named cyanorona-20 was revealed to be more effective on a SARSCoV-2 strain (BetaCoV/Hong Kong/VM20001061/2020) with ECof 0.45 μM which was 209 and 45 times more promising than favipiravir (EC=94 μM) and remdesivir (EC=20 μM)[19,20].

Regardless, favipiravir is effective against influenza virus (type A,B, C) with the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC) ranging from 0.014 to 0.550 μg/mL[21,22]. Favipiravir showed its efficacy on Arenaviridae family (EC=0.79-11.10 μg/mL), Bunyaviridae family(EC=0.9-30.0 μg/mL), and Flaviviridae family (EC=51.8 μg/mL for Yellow fever virus and EC=3.5-3.8 μg/mL for Zika virus)[23-27].

4. Current clinical evidence of the efficacy of favipiravir in COVID-19 treatment

The dosage of favipiravir applied in clinical trials of COVID-19 treatment is 1600 mg twice a day (followed by 600 mg twice a day)or 1800 mg twice a day (followed by 800 mg twice a day) [7,28- 31].However, the regimen of favipiravir of 1600 mg twice a day(followed by 600 mg twice a day) for 10-14 days is more widely reported[7,28,32,33].

Favipiravir treatment is associated with a shorter viral clearance time compared to the control (standard of care)[7,30]. The standard of care in these studies included the provision of oxygen, rehydration,electrolyte correction, and drugs used for systemic symptoms (with the exception of antiviral treatments). The average time to viral clearance was 4 days in the favipiravir group compared to 11 days in the control groups[7]. Shorter viral clearance time was seen in another randomized clinical trial that showed that viral clearance was observed in 62.5% of COVID-19 patients on day 5 compared to 30% that received standard of care[30]. The rate of viral clearance of favipiravir (1800 mg regimen) was similar in both early treatment groups (1 day after participation) and late treatment groups (6 days after participation) among asymptomatic and mild patients[31]. In particular, the viral clearance on day 6 was 66.7% and 56.1% in both early and late treatment groups. The fifty-nine percent logarithmic reduction of viral load by day 6 was insignificantly different between these two groups (94.4% and 78.8% in the early group and late group, respectively)[31]. However, favipiravir was still recommended to be used early (< 3 days) because it reduced mortality in severe cases. For instance, 17% of patients in early treatment died, which was much lower than the rate (38%) in the late treatment group.Also, time of defervescence was shorter in cases using early favipiravir[33,34].

Besides, favipiravir treatment contributed to clinical improvement in mild and moderate COVID-19 patients[28,29]. The clinical recovery rate of ordinary patients was 71.43% in the favipiravir group compared to 55.86% among control groups receiving arbidol(200 mg, three times daily)[26]. In patients with complications such as hypertension and/or diabetes, the treatment group saw a reduction in fever and cough[28]. In another study, the reduction in fever was 73.8% and 66.6% on day 7 in mild and moderate patients revealing its promising efficacy[29]. The defervescence (< 37 ℃ ) in the treatment group (favipiravir) occurred within 2 days on average(for moderate patients) or 2.5 days (for mild patients) after treatment compared to 4 days on average in the control group[30,31]. Regardless,the time to discharge of the favipiravir and control group was likely to be similar, which implied that the treatment did not reduce the hospital stay. For instance, 65% of patients treated with the 1600 mg regimen, 85% of patients treated with the 1800 mg regimen,and 85% of patients receiving standard of care were discharged by day15[30]. Only 40.1% and 60.3% of severe COVID- 19 patients recovered after 7 days and 14 days of treatment, which revealed that treatment in severe patients was not promising[29].

In a case series of 11 severe patients in the intensive care unit(ICU) at the University of Tokyo Hospital, favipiravir was combined with nafamostat mesylate (0.2 mg/kg/day i.p.) and showed positive effects on the clinical conditions of the patients[35]. Seven of eight patients who required mechanical ventilation at the beginning of the treatment period did not require mechanical ventilation after an average of 16 days of treatment. One patient died under a donot-resuscitate order. Two COVID-19 patients with comorbidities,such as diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, and obesity were transferred to the ICU during treatment with the favipiravir 1600 mg regimen and later died[30].

Regarding the improvement shown by para-clinical measures,recovery measured by X-ray examinations or CT scans was observed in 91.43% and 90.0% patients, respectively, compared to standard of care (Table 1)[7,30].

5. Side effects of favipiravir on COVID-19 patients

The most common adverse event was hyperuricemia which was seen in 69 of 82 patients (84.1%)[31]. The increase in alanine aminotransferase and serum triglyceride was reported as 8.5% and 11.0% in the study of Doi et al[31]. Other adverse events reported were fever, mild or moderate including diarrhea, nausea, vomiting,chest pain, and an elevation of liver transaminase levels, injuries of the kidney and liver, and rash[7,30,36]. There were fewer adverse events in the favipiravir groups than in those treated with lopinavir/ritofavir (LPV/RTV)[7]. Tawara et al. reported one case of favipiravir medicinal fever[36], while only 4 patients treated with favipiravir suffered from diarrhea (2 patients), liver and kidney injury (1 patient), and other (1 patient); 25 patients treated with LPV/RTV had diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, rash, liver and kidney injury and others[7]. A meta-analysis also found that side effects in favipiravir groups and standard-of-care groups were insignificantly different[37].In a prospective study of 40 patients, the same side effects were experienced and were self-limited. No patients discontinued favipiravir due to adverse events[38].

However, adverse reactions led to the discontinuation of 2 of 40 (5.0%) patients in the study of Ivashchenko et al[30]. In total,favipiravir has been shown its safety and tolerance when using in the short term[39]. However, there is a need for more evidence in terms of its efficacy in long-term usage. Until then, the drug should be used with caution in case the usage is outside of a clinical trial setting.

6. Antiviral mechanism of favipiravir

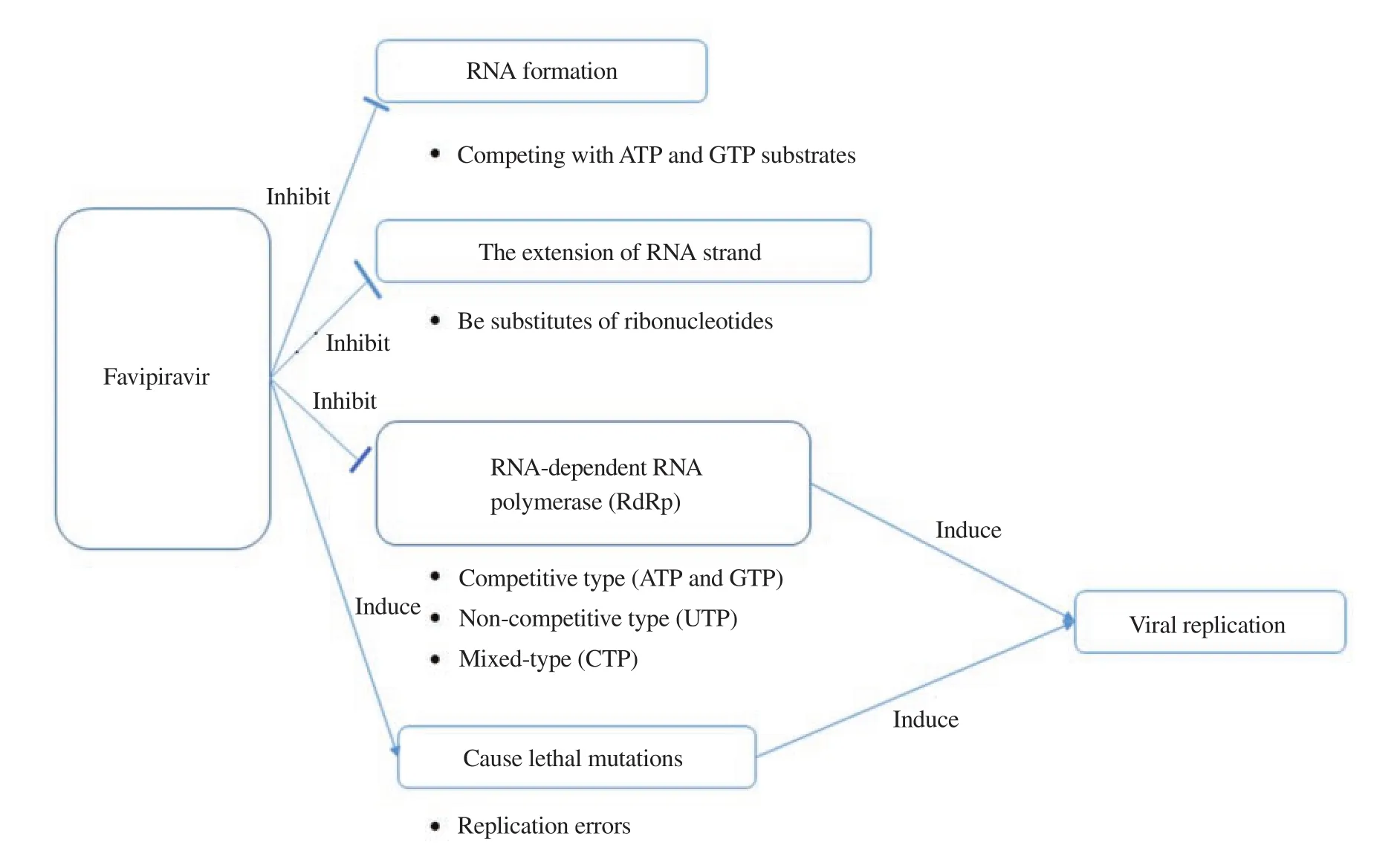

Favipiravir showed its activity via several modes including inhibiting RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), inhibiting the initiation and elongation of RNA formation, preventing the extension of RNA strand of virus, and causing lethal mutations (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mechanism of action of favipiravir against virus.

The ability of inhibition of RdRp was shown on influenza H1N1 virus and H3N2 virus which led to the inhibition of viral replication[21,40]. The inhibition type was competitive for the incorporation of ATP and GTP while mixed-type and noncompetitive types were observed for the incorporation of CTP and UTP, respectively[40,41]. For norovirus RNA polymerase, favipiravir inhibited the initiation and elongation of RNA formation by competing mostly with ATP and GTP substrates[42]. Interestingly,this agent was barely effective at causing chain termination in noroviruses although this was evident in H1N1 virus by competing with ATP and GTP[42,43]. The extension of RNA strand of influenza H1N1 virus was also stopped via incorporating into the RNA strand as substitutes of other ribonucleotides[40].

Another mode of action of favipiravir is to cause lethal mutations of viral RNA (norovirus, H1N1 virus, and SAR-CoV-2). These mutations are anticipated to increase replication errors, in other words, the extinction of viral replication or nonviable viral phenotypes[44]. The rise of mutation frequencies was noticed in the presence of favipiravir in which there were increases in transition rates of A-to-G and U-to-C in norovirus, H1N1 virus, H3N2 virus,and SAR-CoV-2 replication[40,45-47].

The interaction between favipiravir and RNA polymerase was reported in in silico studies. In particular, hydrogen bonds were generated between favipiravir and RdRp of SAR-CoV-2 at amino acid residues ARG750 and ASP608[48,49]. Nevertheless, the in silico analysis showed that there was no interaction between favipiravir and RdRp at the active sites in H1N1 virus[49]. This indicated that the inhibitory activity of favipiravir on the RNA polymerase of influenza virus was attributed to the lethal mutagenesis and replacement of substrates rather than the interaction with the enzyme at the active site.

7. Pharmacokinetic properties of favipiravir

The oral bioavailability of favipiravir is about 97.6%[8]. The concentration of favipiravir in plasma reaches a peak after two hours of administration[50]. However, favipiravir is rapidly eliminated by the kidney before becoming an active form via phosphorylation in tissue. The binding of favipiravir and plasma protein is about 54%[51]. The free drug is metabolized into an inactive form mainly by aldehyde oxidase and partially by xanthine oxidase in the liver with a short half-life time of 2.0-5.5 hours[50].

8. Conclusions

Recognizing the approved status, safety data, and primary measures of the effectiveness of favipiravir in COVID-19 throughout the world, rapid viral clearance, executive recovery rate, and availability as an oral medication with a validated safety profile make it a promising medication for the treatment of COVID-19 in mild and moderate patients. Further insights into the treatment efficacy,safety, and therapeutic role of favipiravir in the management process of COVID- 19 should be established by ongoing clinical trials on favipiravir worldwide. The limitation of favipiravir in the management of the COVID-19 pandemic is that it cannot be offered to expectant or pregnant mothers due to its teratogenic consequences.Advantages of this antiviral intervention on local outbreaks in community transmission are yet to be deciphered. Lastly, the practical efficacy of such an intervention policy will depend on its dose, duration, and cost along with implementation difficulties.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Asian clinical trial network construction project (Number JP20lk0201001j0001). The funders had no role in preparation of the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

NTH developed the concept. DNHT, ATQ, MNL and NTH designed the study. DNT, ATQ, MNL, NTH, TI, KK and KH defined intellectual contents. ATQ, MNL, LT, GMT and LHNM conducted literature search. DNHT, ATQ, MNL, MT, LT, GMT, and LHNM performed data acquisition. DNHT, ATQ, MNL, MT, LT, GMT and LHNM prepared the manuscript. NTH, TI, KK and KH reviewed the initial manuscript. DNHT, ATQ, MNL and NTH edited manuscript to have the final one.

杂志排行

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- Efficacy and safety of ivermectin for COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Prevalence of non-tuberculosis mycobacteria among samples deposited from the National Tuberculous Reference Laboratory of Iran (2011-2018)

- Detection of dengue virus serotype 3 in Cajamarca, Peru: Molecular diagnosis and clinical characteristics

- Prediction of malaria cases in the southeastern Iran using climatic variables: An 18-year SARIMA time series analysis

- Clinical, biochemical and imaging characteristics of adrenal histoplasmosis in immunocompetent patients in a non-endemic area: A case series

- Recovery of child immunization programs post COVID-19