永嘉学派的先驱者——郑氏兄弟

2021-10-21谷峰

谷峰

南宋时,永嘉学派与朱熹道学派、陆九渊心学派鼎足而立,成为中国哲学史上的一个著名哲学流派。永嘉学派集大成者叶适,在述其永嘉学派渊源时,将先辈周行己、郑伯熊、薛季宣、陈傅良作为永嘉学术相承之四大哲人。他在《温州新修学记》中指出:“故永嘉之学、必兢省以御物欲者,周作于前而郑承于后也。”话中的周、郑,指的是周行己和郑伯熊。在此,叶适是将郑伯熊作为永嘉学派中承前启后的一位先驱哲人来评说的。

郑伯熊何许人也?史书上对郑伯熊没有完整的记录,但据零星的记载,今人还是可以了解其大概面貌的。

郑伯熊(约1124-1181),字景望,学者称敷文先生,永嘉县表山村人。郑伯熊出生于一个读书人家庭,父亲郑熙绩曾任温州州学学录(相当于今之市教育局中層干部)。母亲陈氏,出身官宦人家。因此,郑伯熊自少就受到良好教育。郑伯熊私淑周行己,深受关洛之学影响。南宋绍兴十五年(1145),郑伯熊登进士第。绍兴二十年(1150)起,郑伯熊任台州黄岩县尉(相当于今之县公安局局长),后历任婺州司户参军、福建龙溪县丞、国子监丞、婺州知州、宁国府知府等职。淳熙八年(1185),病逝于福建建宁府知府(相当于今建宁市市长)任上,归葬永嘉县东川村澄觉寺北山。

郑伯熊为人刚正不阿,廉洁奉公。绍兴二十年(1150)27岁时任黄岩县尉,年轻敢为,执法如山,正气凛然,高风亮节,人称“石莲县尉”。据宋陈耆卿《赤城(临海)志》的说法:郑伯熊年龄虽小但意志坚定如石,品格似莲花般清洁。

郑伯熊为官体恤民情,为民请命。乾道二年(1166)八月,温州各县发生大水灾,海水倒灌,房屋倾颓,溺死二万余人。时任国子监丞的郑伯熊召开同乡会,联合在朝的乡人,奏请赈济。后朝廷差人赈济,减轻了温州民众的苦难,并迁移一部分福建人充实温州人口。乾道六年(1170)六月,福建八州县遭受旱灾,禾苗枯死,民众苦不堪言。时任提举福建常平茶事的郑伯熊,上书朝廷开常平米仓赈济。朝廷同意郑伯熊的请求,开仓救济,使当地民众度过了荒年。郑伯熊正直立世,不恋官位,乾道九年(1173)任宁国魏王府司马时,魏王傲慢无礼,郑伯熊上书谏劝魏王说:“为人如不具备谦虚的德性,不会被他人认可。”忠言逆耳,魏王很不高兴,郑伯熊请求辞职,朝廷不准,后改任江西提刑。郑伯熊未去赴任,乞祠(自请退职)归家。

郑伯熊的高尚品行来自他高深的学问修养,当时诸多著名文学家、学者都对他的学养给以很高的评价。如果那时有微信,我们会看到这些大咖对郑伯熊的点赞:有门户之见、咄咄逼人的理学家朱熹称誉其文“平和纯正”;文学家叶适恭敬地评其“少而德成,经为人师”;教育家、哲学家袁燮竖着大拇指说:“太守龙图郑公伯熊,当世巨儒也”;永康学派代表人物陈亮赞叹说:“尚书郎郑公景望,永嘉道德之望也”;政治家、文学家周必大肯定说:“景望龙图通经笃行,见谓儒宗。”由此观之,在当时郑伯熊可谓全国学界的代表人物。

郑伯熊重视思想教育,当时奸相秦桧当国,禁止时人学习赵鼎、胡寅的学问,洛学衰落,郑伯熊在福建任职时,不畏秦桧的严令,在全国首次雕版印刊《二程遗书》《外书》《文集》《经说》,设立学校,聚徒二百余人,宣讲洛学,使其重振,影响极大。他在家养病或退职归家时,兴办城西书塾,讲学其间,谆谆善诱,当时学者以宗师视之。那时青年俊彦木待问、陈傅良、叶适、蔡幼学,永康陈亮等均为其学生。其中木待问、陈亮分别为隆兴元年(1163)、绍熙四年(1193)状元及第,叶适于淳熙五年(1178)得中榜眼(第二名),陈傅良、蔡幼学均为进士出身,且陈傅良和叶适后成为永嘉学派的衣钵继承者和集大成者。当时的著名学者楼钥任温州府学教授时,也拜郑伯熊为师。可以说,郑伯熊为当时的教育事业作出了巨大贡献,门下人才荟萃,皆是一代翘楚。

郑伯熊有文集三十卷,有《六经口义拾遗》《戆言》《纪纲》《敷文书说》等,由于当时不像如今那样自费出版成风,郑伯熊著作多散佚,现仅存《敷文书说》27条、《周礼训义》19条,内容简略,不能以窥郑氏学问之全貌。但从现存的几条书说、经义解说,可看出郑氏精通史学,娴熟经制,宗崇孟子性理之学。这样的公众人物,《宋史》却未立传,仅在《宋史·陈傅良传》内带上一笔:“当是时,永嘉郑伯熊、薛季宣皆以学行闻,而伯熊于古人经制治法讨论尤精。”由此可见,郑伯熊虽然宗崇性理之学,但对律法、规章制度和发展经济的实用之学理解很深,比薛季宣还要精深些。不过郑伯熊服膺比他年少十岁的薛季宣的事功学说,与之相交,互相砥砺,探讨事功学问。后来“必弥纶以通世变者”的薛季宣成为永嘉学派的创始者,然作为先驱者的郑伯熊是永嘉学派性理之学转向事功之学的关键人物,他对薛的学问也是有一定影响的。况且, 永嘉学派几位代表人物都是他的学生。可以说,郑伯熊也是该学派创始者。叶适云:“而郑景望书出,明见天理,神畅气怡,笃信固守,言与行应,而后知今人之心可即于古人之心矣。”此是叶对乃师学问的高度评价。撇却郑伯熊对永嘉学派的重大影响,作为道学家的他,在南宋绍淳年间的道学复兴中,他的贡献是不亚于朱熹的。

郑伯熊学问精深渊博,其诗歌有晋唐之风。南宋著名学者周必大在《省斋文稿 · 跋郑景望诗卷》中大赞其诗句有晋唐遗风,胸中学养深不可测。然而,郑之诗集也散佚不见,今仅存九首而已。

郑伯熊的胞弟郑伯英,也是永嘉学派著名学者,与其兄齐名。郑伯英(1130-1192),字景元,晚年自号归愚翁,隆兴元年(1163)进士第四名。在郑伯英中进士时,郑伯熊高兴地说:“兄弟,你超过我了。”然郑伯英任秀州判官,调杭州、泉州推官后,即以养亲为由辞官不出,朝廷也不重新起用,因为他性格刚直,常批评弊政,易得罪君上及同僚权贵。他曾上《中兴急务书》十篇,文章豪迈雄健,极言秦桧之罪, 当权者很是惧怕,不敢提拔他。郑伯英为人尚义,急人所难,喜奖掖后人。叶适《水心集 · 归愚翁文集序》载,郑伯英在家时,热心帮助朋友,经常聚会,不知岁月更替,并乐在其中。郑伯英学问博洽,见闻尤精,讲学独出机杼,见解深颖,深受学者爱戴。郑伯英有文集《归愚集》,今佚失。在当时,人称郑伯熊为大郑公,郑伯英为小郑公,一时年轻学人对二郑兄弟推崇至极。南宋学者、目录学家陈振孙《书录解题》载:“近世永嘉学者推二郑”“二人皆豪杰之士也”

郑伯熊有堂弟郑伯谦,绍熙元年(1190)余复榜进士,曾任衢州府学教授,也为当时著名学者,现仅存《太平经国之书》,是阐述《周礼》一些制度的著作,凭此书已无法了解其全面的学术成就。《宗元学案·卷三十二》将郑伯熊与郑伯英合传外,还将郑伯谦列为“家学”,可见他也是永嘉学派的中坚人物。另有堂弟郑伯海,绍兴二十一年(1151)进士,授海门尉、知南昌县、擢知英德府,后任沿海制置司参议、制置使。郑伯海家居时,设立义塾,聘请名师授徒,有学生500人。郑伯海家与郑伯熊家相距百余步,人称“东西二郑”。

据《宗元学案 · 周许诸儒学案》载:“乾淳之间(1165-1189),永嘉学者连袂成帷,然无不以先生兄弟为渠率(领袖)。”意思是说,乾淳朝二十多年來,作为永嘉学派先驱者的郑伯熊兄弟,带领众多的永嘉学者,研究学问,宣扬事功,为永嘉学派的开创贡献了思想精华。

The Zheng Brothers:

Forerunners of the Yongjia School of Thought

By Gu Feng

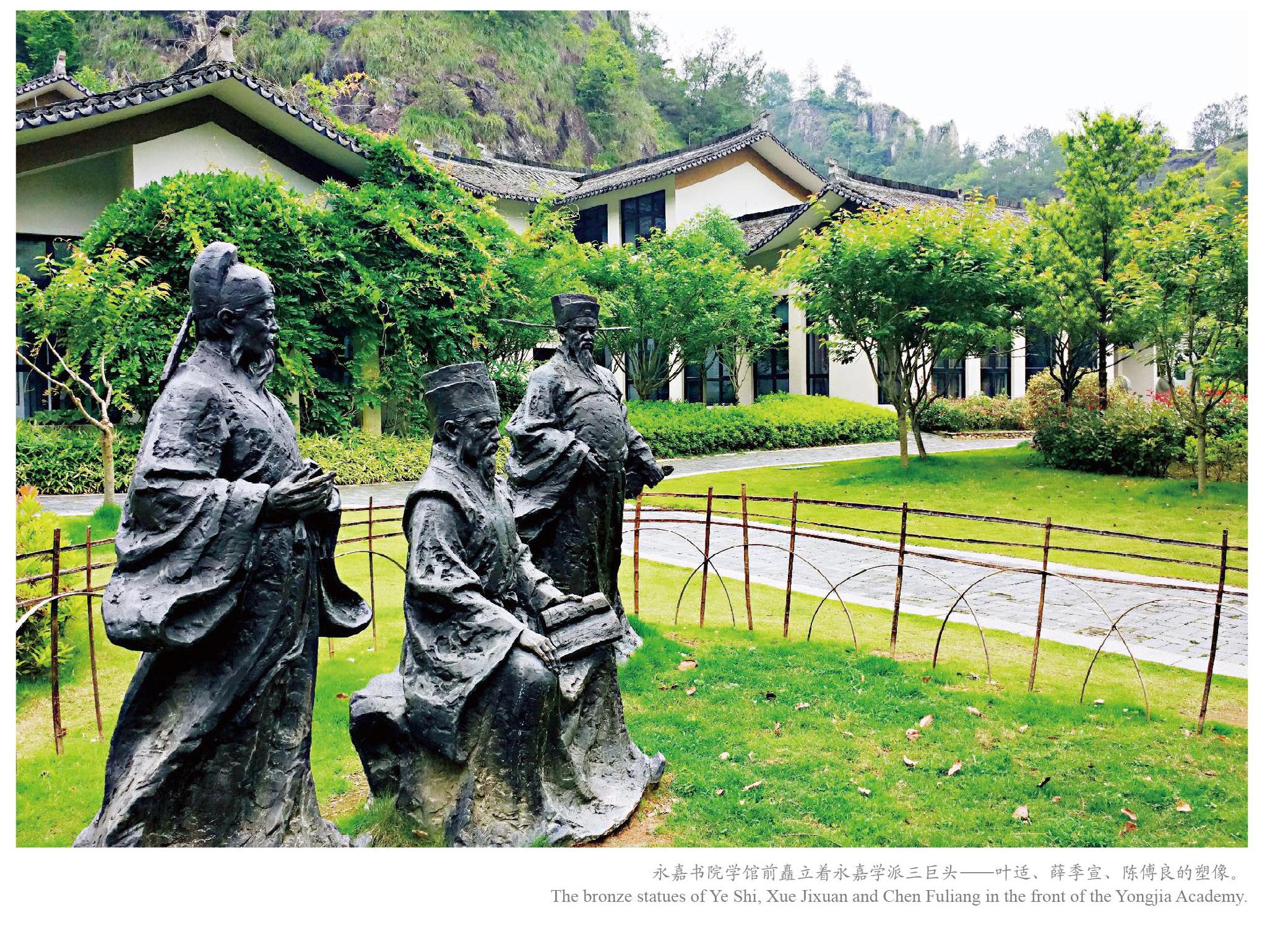

The Yongjia School of Thought or simply Yongjia School was one of the three most influential philosophical schools, along with the School of Principle represented by Zhu Xi (1130-1200) and the School of Mind founded by Lu Jiuyuan (1139-1192), during the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279). When tracing its origins, Ye Shi (1150-1223), widely believed to be the doyen of the Yongjia School, counted Zhou Xingji (1067-1125), Zheng Boxiong (ca. 1124-1181), Xue Jixuan (1134-1173) and Chen Fuliang (1137-1203) as the four great philosophers who had established and developed the school.

Ye Shi once wrote, “Therefore, the learning of Yongjia and the idea to guard against material desire was initiated by Zhou and further developed by Zheng.” The “Zhou” and the “Zheng” refer to Zhou Xingji and Zheng Boxiong, and here, apparently, Ye had regarded Zheng as a pioneering figure of the Yongjia School who had helped solidify its status.

But who was Zheng Boxiong? While historical records are somewhat sketchy when it comes to Zheng, with those available bits of documents and information, a rough picture of who he was could still be pierced together.

A native of Biaoshan village in Yongjia county, Zheng Boxiong was given the countesy name Jingwang and was called Master Fuwen by scholars. Born into a literary family, he received very good education at a young age. Zheng Xiji, Zheng Boxiongs father served as a mid-level official in Wenzhous education system. His mother, nee Chen, also came from a family whose members held public offices. In 1145, Zheng ranked first class in the imperial examination, and was conferred the title of metropolitan graduate with honors (jinshi jidi). Since 1150, he held a string of positions in Wuzhou (present-day Jinhua city), Fujian province, the Directorate of Education and Anhui province, among others. In 1185, Zheng died of illness while serving as the prefect of Jianning (present-day Jianning city) in Fujian province. He was buried at the northern hill of the Chengjue Temple at Dongchuan village, Yongjia county.

Zheng was known for his uprightness and incorruptibility. In 1150, when he acted as the county magistrate of Huangyan county at the young age of 27, he had already shown his braveness and decisiveness in enforcing laws. Chen Jiqing (1180-1236), a Southern Song scholar, praised Zheng in the Annals of Chicheng (present-day Linhai city): young as he was, Zheng Boxiong was as firm as a rock, and his character was as pure as a lotus flower, which earned him the title “Magistrate Stony Lotus”. Indeed, as the commander of military office for Prince Wei in 1173, he advised the prince against being so insouciant, as “those who lack humility will not be acknowledged by others.” Unsurprisingly, the advice was not taken too kindly by Prince Wei, and Zheng resigned in protest.

As an official, Zhengs compassion for the common people was evident. In August 1166, a deluge hit the area of Wenzhou. Coastal flooding flattened houses and drowned over 20,000 people. As the Proctor of the Directorate ofEducation, Zheng convened a meeting with fellow Wenzhouese in the capital, and, together with officials of Wenzhou origins serving in the imperial court, he asked the emperor for help, which was granted. Official relief later greatly lessened the suffering of Wenzhou people; in fact, a number of residents from neighboring Fujian province were also relocated to replenish the Wenzhou population. In June 1170, Zheng called for governmental relief when Fujian, where he served as the supervisor of taxation, salt and tea, was hit bu severe draught. Once again, heeding his plea, the imperial court offered relief and helped local people tide over the difficulties.

Erudite and cultured, Zhengs noble character had a lot to do with his learning. Many a philosopher and scholar at the time spoke highly of him. Zhu Xi considered Zheng “honest and refined”; Yuan Xie (1144-1224), educator and philosopher, celebrated him as “a great Confucian master of our time”; Chen Liang (1143-1194), statesman and philosopher, called Zheng “a moral beacon of Yongjia”; and Ye Shi lauded him as “a man of virtue and integrity since very young and a model teacher”.

A model teacher Zheng was, for he made great contributions to education. While holding public office in Fujian, he set up schools and published rare Neo-Confucian books, which greatly extended its influence. Young and upcoming Confucian scholars like Ye Shi and Chen Fuliang, who would go on to become masters of the Yongjia School, were all Zhengs students. His writings were also highly acclaimed: his poems were regarded by his contemporaries as being reminiscent of those from the Jin (265-420) and Tang (618-907) dynasties. Unfortunately, most of Zhengs poems have been lost and only nine have survived.

Born in the year 1130, Zheng Boying was one of leading figures of the Yongjia School as well, and was as well known as his elder brother Zheng Boxiong. Courtesy named Jingyuan, Zheng Boying called himself Gui Yu Weng (literally “Returning Foolish Old Man”) in the latter years of his life. He died in 1192.

In 1163, Zheng Boying ranked fourth in the imperial examination, and when Boxiong heard of the news, he gladly declared to Boying, “my brother, you have bettered me.” However, Boying resigned from office just serving one term as the assistant prefect of Xiuzhou (present-day Jiaxing), which the imperial court was perhaps more than happy to accept, for Boying was known for his outspoken and acerbic criticisms of the establishment and could easily make himself an enemy of the powers that be. Nonetheless, like his elder brother, Boying was highly respected by his friends and fellow scholars. Chen Zhensun (1179-1262), a Southern Song bibliographer, thus commented on them, “of the recent Yongjia scholars, the two Zhengs are the foremost” and “both are heroic figures”.

Zheng Boqian, Zheng Boxiongs cousin, was also an important scholar of the Yongjia School. His only surviving book Taiping Jingguo Zhi Shu (or the Book of Governance during Peace Times) is an exposition on Zhou Li (or the Rites of Zhou), from which the full extent of his academic achievements could never be gleaned. Zhen Bohai, also Zheng Boxiongs cousin, was yet another public official and educator. During his retirement, Bohai set up a private school which recruited over 500 students.

As the authors of Song Yuan Xue An (or Annals of Scholars in the Song and Yuan Dynasties), a history of Confucian philosophy during the period, observed, “during the reign of Qianchun (1165-1189), a great number of Yongjia scholars emerged, and without exception, they had all looked to the Zheng brothers as the leaders.”