Probiotics in hepatology: An update

2021-10-11RomanMaslennikovVladimirIvashkinIrinaEfremovaElenaPoluektovaElenaShirokova

Roman Maslennikov, Vladimir Ivashkin, Irina Efremova, Elena Poluektova, Elena Shirokova

Roman Maslennikov, Vladimir Ivashkin, Irina Efremova, Elena Poluektova, Elena Shirokova, Department of Internal Medicine, Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Sechenov University, Moscow 119435, Russia

Roman Maslennikov, Vladimir Ivashkin, Elena Poluektova, Scientific Community for Human Microbiome Research, Moscow 119435, Russia

Roman Maslennikov, Department of Internal Medicine, Consultative and Diagnostic Center of the Moscow City Health Department, Moscow 107564, Russia

Abstract The gut–liver axis plays an important role in the pathogenesis of various liver diseases. Probiotics are living bacteria that may be used to correct disorders of this axis. Notable progress has been made in the study of probiotic drugs for the treatment of various liver diseases in the last decade. It has been proven that probiotics are useful for hepatic encephalopathy, but their effects on other symptoms and syndromes of cirrhosis are poorly studied. Their effectiveness in the treatment of metabolic associated fatty liver disease has been shown both in experimental models and in clinical trials, but their effect on the prognosis of this disease has not been described. The beneficial effects of probiotics in alcoholic liver disease have been shown in many experimental studies, but there are very few clinical trials to support these findings. The effects of probiotics on the course of other liver diseases are either poorly studied (such as primary sclerosing cholangitis, chronic hepatitis B and C, and autoimmune hepatitis) or not studied at all (such as primary biliary cholangitis, hepatitis A and E, Wilson's disease, hemochromatosis, storage diseases, and vascular liver diseases). Thus, despite the progress in the study of probiotics in hepatology over the past decade, there are many unexplored and unclear questions surrounding this topic.

Key Words: Gut-liver axis; Pathogenesis; Gut dysbiosis; Gut microbiota; Gut microbiome; Liver disease; Probiotics; Hepatic encephalopathy; Cirrhosis; Metabolic associated fatty liver disease; Alcoholic liver disease; Primary sclerosing cholangitis

INTRODUCTION

It has been 10 years since theWorld Journal of Gastroenterologypublished an article titled “Probiotics in Hepatology”[1]. The following decade was marked by tremendous progress in the study of the gut-liver axis[2,3]. It was shown that the gut microbiota plays an important role in the development of various liver diseases. Probiotics are drugs that target it[4]. The aim of this review is to describe the current data on the use of probiotics for the treatment of liver diseases.

SCIENTIFIC BASIS FOR THE USE OF PROBIOTICS IN LIVER DISEASES

Gut dysbiosis[5-7], small intestinal bacterial overgrowth[8,9] and an increase in the permeability of the intestinal wall[10] leads to bacterial translocation in cirrhosis[11,12]. The latter leads to systemic and liver inflammatory reaction, as well as hemodynamic changes[13], and contributes to the development of complications of cirrhosis, such as ascites, esophageal varices, and hepatorenal syndrome[2,11,12]. In addition, the gut microbiota produces a variety of neuroactive products of protein metabolism, which are normally removed by the liver and abundantly enter the bloodstream, leading to the development of hepatic encephalopathy, in cirrhosis[14].

The gut microbiota plays an important role in the regulation of metabolism in our body. It modifies bile acids (deconjugation, conversion of primary into secondary), which through their receptors [farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and Takeda G-protein receptor 5], have a variety of effects on the metabolism[15,16]. In addition, the gut microbiota forms short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), which through their receptors, also have a complex effect on metabolism and maintain intestinal barrier integrity[17]. Gut dysbiosis leads to disorders of these regulatory functions, which can result in metabolic changes.

Alterations in gut microbiota and increased intestinal permeability were also described in alcoholic liver disease[18,19], metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD)[20], primary sclerosing cholangitis[21,22], and autoimmune hepatitis[23]. Gut dysbiosis was also reported in primary biliary cholangitis[24], Wilson’s disease[25], hepatitis B[26] and hepatitis C[27] recently.

At the same time, probiotics have shown their ability to correct gut dysbiosis[28], increase production of SCFA[29], and reduce the increased permeability of the intestinal barrier[30]. All this constitutes the scientific basis for their use in the treatment of liver diseases.

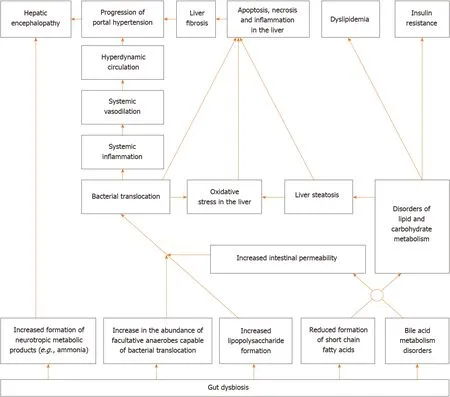

A simplified diagram of the gut-liver axis is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Simplified diagram of the gut-liver axis.

PROBIOTICS FOR CIRRHOSIS

According to the latest meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCT), the use of probiotics is effective in the treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy and prevents the development of overt hepatic encephalopathy. Probiotics are as effective in treating minimal hepatic encephalopathy as rifaximin, lactulose, and L-orinithin-Laspartate. There was no effect of probiotics on mortality. The addition of lactulose to probiotics did not significantly affect the effectiveness of the treatment. Probiotics lower blood ammonium levels more than lactulose. The addition of lactulose to probiotics paradoxically increases blood ammonium levels. The use of probiotics was not accompanied by the development of significant side effects[31]. Other recent metaanalyses have reached similar conclusions[32,33].

Several RCTs that studied the effect of probiotics on other indicators in cirrhosis been published.

The use of probiotics (Clostridium butyricumcombined withBifidobacterium infantis) in minimal hepatic encephalopathy led to a decrease in the abundance of harmful Enterococcus and Enterobacteriaceae in the gut microbiome. The blood levels of markers of bacterial translocation [lipopolysaccharide (LPS)], intestinal permeability (D-lactate) and damage to the intestinal epithelium (diamine oxidase) also decreased in these patients[34]. The use of probiotic beverage Yakult 400 also led to a decrease in the abundance of Enterobacteriaceae in the gut microbiome[35]. In another RCT, administration of Lactobacillus GG for 8 wk led to an increase in the proportion of beneficial bacteria (LachnospiraceaandClostridia XIV) and a decrease in the proportion of harmful ones (Enterobacteriaceae). Moreover, this was accompanied by a decrease in endotoxemia and systemic inflammation[36].

Administration of a probiotic for cirrhosis leads to an improvement in cognitive functions and an increase in gait speed, but does not significantly affect the risk of falling and the hand grip muscular strength[37].

A recent meta-analysis showed that administration of probiotics for cirrhosis does not significantly affect C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin (IL)-6 Levels, but leads to a decrease in tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) level[38].

ProbioticLactobacillus casei(L. casei) Shirota application for 6 mo did not have a significant effect on neutrophil function, the blood level of LPS and most cytokines, frequency of bacterial DNA detection in blood, intestinal permeability (but it was baseline normal), quality of life, indicators of the complete blood count, or liver and kidney function in non-severe cirrhosis (Child-Pugh scores < 11)[39].

The use of a multi-strain probiotic containing several species ofBifidobacteriumandLactobacillusfor non-severe cirrhosis (Child-Pugh scores < 12) showed similar results[40]. However, the intake of this probiotic led to an increase in the abundance ofFaecalibacterium prausnitzii,Syntrophococcus sucromutans,Bacteroidetes vulgatus,Prevotella,andAlistipes shahiiin the fecal microbiome. At the same time, the abundance ofBifidobacterium bifidum,Lactobacillus acidophilus(L. acidophilus), andL. caseiremained unchanged[41].

One of the most studied probiotics for cirrhosis is VSL#3, a mixture containing eight bacterial strains. Its use for 6 mo led to a decrease in the Child-Pugh and MELD scale values, the blood level of IL-1b and IL-6, TNF-α, aldosterone, renin, brain natriuretic peptide, ammonia, and indole, as well as the risk of hospitalization, but did not significantly affect mortality[42]. Its use for 2 mo in patients with large esophageal varices without a history of bleeding improves their response to propanolol[43]. Administration of this probiotic for 28 d did not lead to any significant change in the blood content of the plasminogen activator inhibitor and vascular endothelial growth factor, but led to an increase in the blood levels of large endothelin and nitric oxide and a decrease in the blood levels of thromboxane B2[44]. In addition, the use of this probiotic for 6 wk led to a decrease in the hepatic venous pressure gradient, cardiac output, and heart rate and an increase in systemic vascular resistance and sodium levels in the blood, but did not significantly affect the mean pulmonary artery pressure[45]. However, the last two studies were not controlled. VSL#3 also prevents the development of endothelial dysfunction in experimental models of cirrhosis[46].

Probiotics reduce the risk of development of re-bleeding from esophageal varices after endoscopic treatment in cirrhosis according to a retrospective study. Moreover, the larger the dose of the probiotic, the more pronounced the effect[47].

The probiotic tolerance was excellent and there were no significant side effects in any of the cited studies. However, cases of the development of spontaneous bacterial periotinitis[48] and fatal endocarditis[49] caused by probiotic strains, which was consumed by a patient with cirrhosis for a long time, are described.

Summarizing these data, we can deduce the aforementioned facts. The effectiveness of probiotics in the treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy and in the prevention of development of overt hepatic encephalopathy has been confirmed by a series of meta-analyses and is beyond doubt. In addition, most studies have shown an improvement in the profile of the gut microbiota after following administration. At the same time, the influence of probiotics on other characteristics of patients with cirrhosis (intestinal permeability, bacterial translocation, systemic inflammation and others) differs from study to study. Perhaps this is due to the fact that different probiotic strains were used, which had different effects on these indicators. It would be helpful to conduct studies that directly compare probiotics that have shown and not shown an effect on these biomarkers.

The suggested mechanism of action of probiotics in cirrhosis is shown in Figure 2.

PROBIOTICS FOR ALCOHOLIC LIVER DISEASE

The use of probiotics led to a decrease in the level of steatosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and cell death in the liver, a decrease in the level of biomarkers of systemic inflammation, bacterial translocation, gut dysbiosis, dyslipidemia, damage to the intestinal epithelium, and intestinal permeability in experimental alcoholic liver disease (Table 1)[50-54]. Probiotics restore the alcohol-damaged epithelial barrier in the intestines by epidermal growth factor receptor activation[55]. Functioning of this receptor is also required for the protective effect of probiotics in alcoholic liver disease[55]. Probiotics suppress alcohol-induced apoptosis of hepatocytes[56].

These effects are not just due to the living bacteria themselves, which are part of the probiotics, but also the supernatant of their culture[57].

However, unlike many published experimental results, there are very few clinical trials on the effectiveness of probiotics in alcoholic liver disease. There was no effect of the probiotics (Lactobacillus subtilisandStreptococcus faecium) on total protein, cholesterol, or IL-1b levels in the blood according to RCT. The probiotics blocked the growth of blood LPS level in alcoholic hepatitis, but only in the cirrhosis subgroup.The number ofEscherichia colidecreased in the feces in the probiotics groups. Changes in the levels of other biomarkers were not compared between the probiotic and placebo groups in this RCT[58].

It was shown that probiotics led to a more pronounced decrease in the activity of transaminases in the blood than standard therapy while significantly having no effects on the level of total bilirubin and GGT in alcoholic steatohepatitis in an earlier RCT[59].

Thus, the encouraging results of the use of probiotics in the treatment of alcoholic liver disease, obtained in experimental models, need to be confirmed by a large number of clinical trials.

PROBIOTICS FOR METABOLIC ASSOCIATED FATTY LIVER DISEASE

The use of probiotics led to a decrease in the level of steatosis, lipogenesis, oxidative stress, and inflammation in the liver, a decrease in the level of biomarkers of insulin resistance, bacterial translocation, gut permeability, and systemic inflammation and a decrease in blood level of lipids and glucose and in expression of the inflammation activator receptor genes (toll-like receptors 4 and 9, and NLRP3) in the liver in experimental MAFLD (Table 2)[60-66]. It also leads to a decrease in the LPS content and an increase in the bile acid content in feces[62,67], increases the content of cholesterol 7αhydroxylase, which converts cholesterol to bile acids, and transporters of bile acids into bile in the liver[62], enhances the transfer of Nrf2 (transcription factor of antioxidant defense genes) to the nucleus[66], transfers metabolism from carbohydrate utilization to fat utilization[63], increases the acetate and butyrate level in feces[68], improves gut microbiome structure by increasing the abundance of gram-positive bacteria such as Firmicutes and decreasing gram-negative bacteria such as Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Fusobacteria[69], but does not affect the degree of cholesterol reabsorption[63].

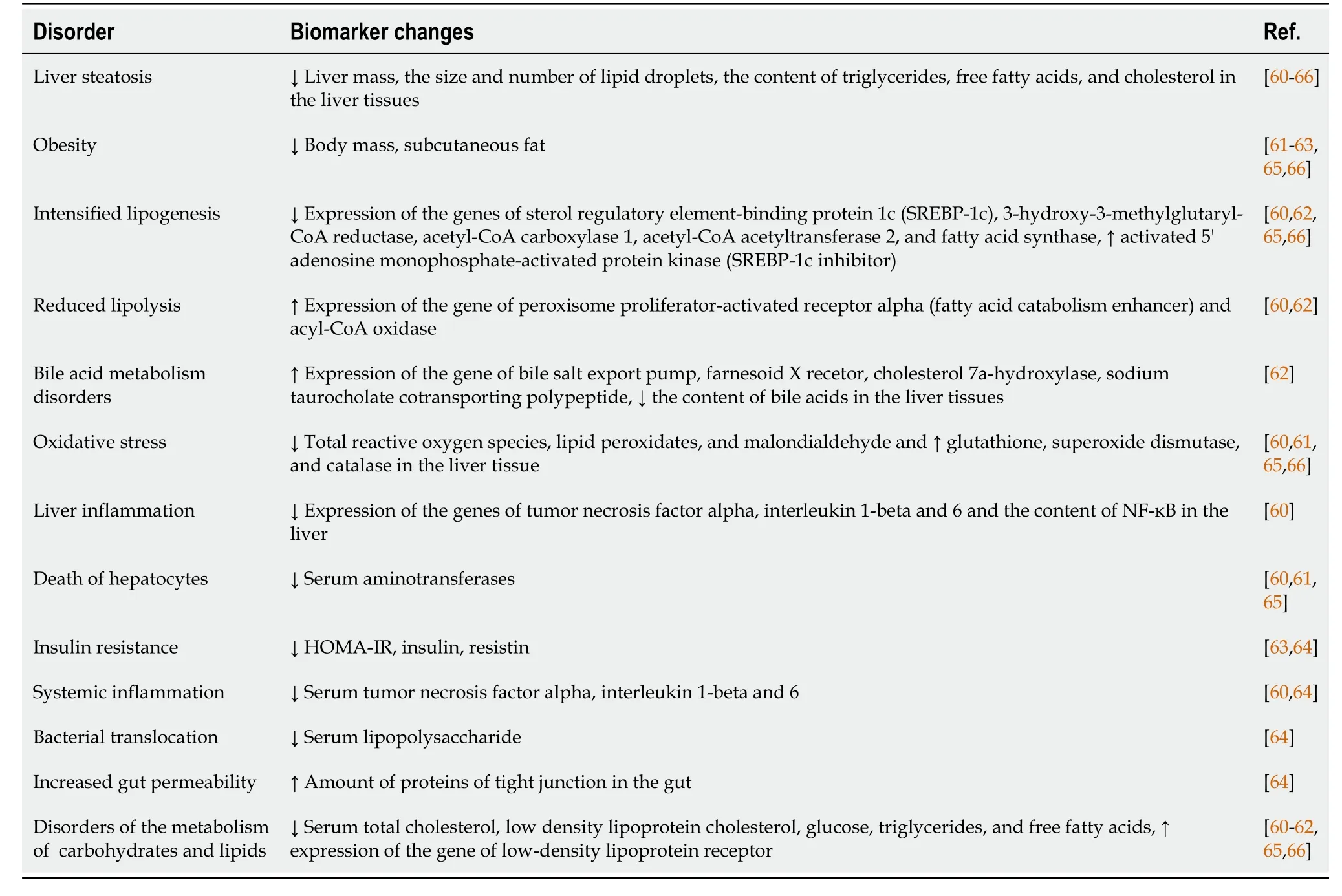

Table 1 Effects of probiotics on different disorders in experimental alcoholic liver disease

Some of these effects can be achieved using the supernatants of the cultures of live probiotics[70].

Butarate, formed by probiotic strains, enhances the formation of tight junction proteins, as well as activates 5' adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (inhibits lipogenesis) and increases the lifetime of Nrf2 in cell culture[71].

Consuming yogurt four times or more per week reduces the risk of developing MAFLD[72].

A number of systematic reviews with meta-analyses describing the effect of probiotics on the course of MAFLD were published recently. The meta-analysis, including 105 studies of patients with MAFLD and/or its underlying disorders (obesity and/or diabetes), showed that administration of probiotics leads to a decreasein body weight, body mass index, waist circumference, body fat mass, visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue mass, fasting glucose, glycated hemoglobin, insulin, HOMA-IR, ALT, AST, triglycerides and CRP[73]. A meta-analysis that included 22 studies of patients with MAFLD showed that probiotics lower weight, body mass index, ALT, AST, GGT, ALP, total cholesterol, LDL-C, triglycerides, glucose, insulin, TNF-α, leptin, and liver steatosis and do not significantly affect waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, fat mass, serum albumin, HDL-C, HOMA-IR, CRP, or IL-6[74]. Other meta-analysis came to broadly similar conclusions[75]. The fourth meta-analysis showed that administration of probiotics for MAFLD resulted in a decrease in liver fibroscan stiffness[76].

Table 2 Effects of probiotics on different disorders in experimental metabolic associated fatty liver disease

Several new RCTs have been published following these meta-analyses.

The use of a multi-strain probiotic for 1 year in patients with metabolic associated steatohepatitis (MASH) resulted in a decrease in the severity of ballooning necrosis and fibrosis, without significantly affecting steatosis and inflammatory infiltration of liver compared to the placebo. Moreover, the level of bilirubin, ALT, ALP, leptin, TNFα, IL-1b, IL-6, and LPS decreased in the blood, without significant difference in HOMA-IR and body weight[77].

The use of another multi-strain probiotic for 12 wk led to, among other things, a decrease in liver fat content according to MRI data and an increase in theBacteroidetes/Firmicutesratio[78].

A combined probiotic (Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus and Enterococcus, 1 g two times per day, 3 mo) in histologically verified MAFLD lowered the serum levels of ALT, AST, GGT, total cholesterol, triglycerides, and HOMA-IR and the value of the histological scale of steatohepatitis activity NAS, and proportion of patients with dysbiosis, but did not significantly affect the serum levels of total bilirubin and high density lipoprotein cholesterol[79].

The use of a probiotic (L. casei, L. rhamnosus, L. acidophilus, Bifidobacterium longum, andB. breve) for MASH led to a decrease in the serum levels of triglycerides, ALT, AST, GGT, and ALP, but did not significantly affect fasting blood sugar, the serum levels of cholesterol and its fractions, CRP, weight, body mass index, percent body fat, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio[80].

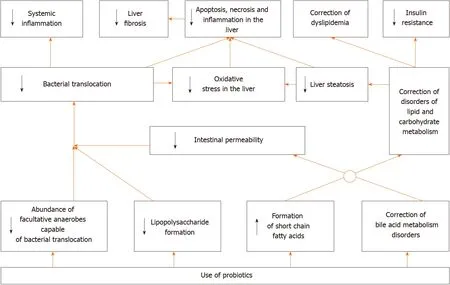

In general, it can be argued that RCTs and their meta-analyses have confirmed most of the results obtained in experimental models of MAFLD. However, we did not find any studies that described the effect of probiotics on prognosis in this disease, which is a challenge for future researchers. Based on the data obtained, the following mechanism of the development of positive effect of probiotics in MAFLD can be assumed (Figure 3).

Figure 2 Suggested mechanism of action of probiotics in cirrhosis.

Figure 3 Suggested mechanism of action of probiotics in metabolic associated fatty liver disease.

PROBIOTICS FOR VIRAL HEPATITIS

Unlike for cirrhosis, alcoholic and MAFLD, probiotics have hardly been researched as drugs for viral hepatitis. Perhaps this is due to the fact that, unlike these diseases, effective therapy for viral hepatitis already exists.

Long-term use of a probioticEnterococcus fecalisstrain FK-23 in chronic viral hepatitis C led to a decrease in ALT and AST levels, with no significant effect on viral load, blood total protein, urea and hemoglobin levels, and platelet count in an uncontrolled clinical study[81].

Bifidobacterium adolescentisSPM0212 showed antiviral effects against hepatitis B virus in cell culture[82].

PROBIOTICS FOR CHOLESTATIC DISEASES

The use ofL. rhamnosusGG reduced the biochemical and histological signs of hepatitis, cholestasis, and fibrosis after ligation of the common biliary duct in mice. Perhaps the reason for this is that probiotics increases the activity of FXR in the intestine. This receptor enhances the formation of fibroblast growth factor 15 (FGF15) in response to stimulation with bile acids. FGF15 reduces the production of bile acids in the liver due to negative feedback. With cholestasis, few bile acids enter the intestine, this receptor is not activated enough, the FGF15 content in the blood decreases, and the formation of bile acids in the liver increases. The latter, with cholestasis, have a toxic effect on the liver, which is manifested by its inflammation and fibrosis. The intake of this probiotic led to an increase in the activity of FXR in the intestine and FGF15 in the blood, which close this feedback, protecting the liver from autointoxication with bile acids. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the use of powerful antagonists of FXR blocks the positive effect of the probiotic in this case and the culture supernatant of this probiotic increases the activity of this receptor in tissue cultures[83].

In addition,L. rhamnosusGG increases the content of Firmicutes and Actinobacteria in the gut microbiota, which convert primary bile acids into secondary ones, which are poorly absorbed, and therefore, removed with feces. There is a significant increase in the content of bile acids due to secondary ones, with an absolute and relative decrease in the content of primary bile acids in the feces of such animals. That is, administration of this probiotic for cholestasis leads not only to a decrease in the formation of new bile acids, but also to an increase in the removal of already formed ones with the feces[83].

L. rhamnosusGG has a similar protective effect in another model of cholestatic liver damage, in which the excretion of bile acids is blocked due to the knockout of the gene of their transporter multidrug resistance protein 2[83]. The use ofL. casei rhamnosuswas as effective as neomycin in preventing cholangitis in patients with biliary atresia who underwent Kasai operation[84].

The use of probiotics for primary sclerosing cholangitis combined with inflammatory bowel diseases did not have a significant effect on pruritus, fatigue, serum level of bilirubin, ALP, GGT, AST, ALT, prothrombin, albumin, and bile salts in a very small RCT that included 14 patients[85].

We did not find any other clinical trial of probiotics in chronic cholestatic diseases. Given the very encouraging results of the experimentary study, a large RCT on this topic seems to be very interesting.

PROBIOTICS FOR AUTOIMMUNE HEPATITIS

We found only one study describing the effect of probiotics on liver condition in experimental autoimmune hepatitis. It was shown that they lead to a decrease in the formation of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1b in the liver, as well as in the proportion of Th-17 cells among CD4+ lymphocytes in the liver and spleen[86]. Further experimental studies and clinical trials are needed to clarify the usefulness of probiotics in the treatment of this disease.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the study of probiotics in hepatology is uneven. It has been proven that they are useful in hepatic encephalopathy, but their effect on other symptoms and syndromes of cirrhosis is poorly studied. Their effectiveness in the treatment of MAFLD has been proven both in experimental models and in clinical trials, but their effect on the prognosis of this disease has not been described. The beneficial effects of probiotics in alcoholic liver disease have been well shown in many experimental studies, but there are very few clinical trials to support them. The effect of probiotics on the course of other liver diseases is either poorly studied (primary sclerosing cholangitis, chronic hepatitis B and C, autoimmune hepatitis), or not studied at all (primary biliary cholangitis, hepatitis A and E, Wilson's disease, hemochromatosis, storage diseases, vascular liver diseases,etc.).

杂志排行

World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Coronavirus disease 2019 and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- Epigenetic mechanisms of liver tumor resistance to immunotherapy

- Advances in the management of cholangiocarcinoma

- Herbal and dietary supplement induced liver injury: Highlights from the recent literature

- Challenges in the discontinuation of chronic hepatitis B antiviral agents

- Liver Kidney Crosstalk: Hepatorenal Syndrome