中国职务发明纠纷多元解决机制探究

2021-08-03韩威威

韩威威

Exploring Diverse Dispute Resolution Mechanisms for Service Inventions in China

Han Weiwei

(School of Intellectual Property, East China University of Political Science and Law, Shanghai 200042, China)

Abstract: The increase in both service inventions and disputes on service inventions in China has drawn considerable public attention to related disputes, making effective and efficient dispute resolution a critical, note-worthy issue. Related dispute resolution practices in civil law jurisdictions such as Germany and France and common law jurisdictions such as the United States and the United Kingdom are analyzed, drawing comparisons with current Chinese practices. Efficient resolution of disputes surrounding service inventions would see the establishment of specialized boards or commissions in cities where the intellectual property courts are located. Moreover, the coordination of mediation, arbitration and judicial proceedings in substance and procedure is expected, so that they work collectively towards smooth and effective dispute resolution for service inventions. With the goal of encouraging innovation, balancing the benefits of employers and employees, as well as realizing the establishment of an innovation-oriented country, suggestions on consolidating diverse mechanisms in current Chinese practices are advanced with references to recent Patent Law amendments and the Guidelines for Administrative Mediation Concerning Patent Disputes.

Key words: service invention; employee invention; arbitration proceedings; judicial proceedings; patent disputes

CLC: D 915 DC:A Article ID:2096-9783(2021)02-0128-13

1 Introduction

Economic growth and international competitiveness in a national economy are conditional upon the implementation of inventions in technology and commercial production[1]. Service inventions, also known as "employees' inventions" or "employee inventions" in certain countries like Germany and the United Kingdom, are an integral part of an industrialized country. They arose with the arrival of industrialism, and expedite the pace of technological innovations. In many countries such as Germany, employee inventions account for a majority of their inventions[2]. Seeking to negotiate a balance between the benefits of employers and employees, as well as to encourage innovation, countries have promulgated their own legal provisions. Such provisions prescribe the ownership of employee inventions, remuneration for employee inventions, and proceedings for resolving attendant disputes, among others. It is known that the ownership of employee inventions is a critical issue and closely related to the individual contribution(s) of an employer and an employee[3].

In China, the Patent Law and the Implementing Regulations thereof make provisions for service inventions. Article 61 and Article 162 of the former address, respectively, ownership of employees' inventions as well as the reward and remuneration for service inventions. Specific manners for calculating the reward or remuneration are illustrated in Rules 76-78 of the latter. Apart from the mechanism for reward and remuneration contained in legal regulations, innovation is also incentivized by national or regional policy.

An innovative environment in China, including the reward and remuneration for service inventions, the policy of encouraging innovation, and the realization of the value of intellectual property, among others, has seen an increase in the number of patents based on service invention. The proportion of such service-invention patents as part of the total amount of patents granted has also increased. Particular attention has been paid to the amount of invention patents based on service inventions (referred to as "service-invention patents" hereinafter) and their percentage in the invention patents as granted. As demonstrated by the annual statistic data from the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA), the number of domestic service-invention patents granted in 2010 was 66,1493, which accounts for 82.9% as compared to the total amount of 79,7674 patents granted in the same year. The annual number of service-invention patents has been steadily increasing over the past years. Ten years after, 344,3615 service-invention patents were granted, amounting to 95.4% of the total 360,9196 patents granted in 2019. It can be seen that service-invention patents occupied a dominant portion of the patents granted in the same year.

With the recent amendment to the Patent Law, it is to be expected that the number of service-invention patents will continue to increase in the near future. The fourth amendment to the Patent Law further encourages the application of service inventions. For example, Article 6 of the Patent Law now includes the following clause: "[t]he entity can legally deal with the right thereof to apply an invention-creation patent application and patent right, and advance the implementation and exploitation of relevant invention-creations." In addition, multiple manners are newly introduced into Article 15 (pending Article 16) of the Patent Law to reward the inventors of a service-invention patent in the following ways: "[t]he State encourages the entity granted with a patent right to implement property right incentives and adopt equity, options, dividends and other means to enable inventors or designers to reasonably share the profits of their innovation."

The increase in service inventions and service-invention patents has also led to a plethora of attendant disputes[4]. For instance, a preliminary keyword search using the term "service invention" on the official website for searching Chinese court decisions7 shows that only 6 cases were heard and decided in 2010; in 2019, however, the number of court cases rose more than forty-fold to 263. A report from the Supreme People's Court notes that, among the cases decided by the Intellectual Property Tribunal of the Supreme People's Court in 2019, seven cases arose from disputes relating to remuneration for employees responsible for service inventions[5].

Currently, there are two main routes for resolving disputes on service inventions: judicial proceedings and mediation proceedings. Despite being a crucial mechanism for resolving disputes arising from service inventions, judicial proceedings carry the downside of time-consuming litigation, which may last for several years. Moreover, the results may not be advantageous for the employer-employee relationship. For the other option, based on statistical data and case analysis, it was concluded that it is difficult to reach settlement via mediation8.Arbitration was addressed to solve such disputes in the Draft Regulations on Service Inventions (Draft for Review) which was issued in 20159; unfortunately, the Draft Regulations have not come into effect. It is debatable whether arbitration is applicable or suitable for disputes on service inventions. There is still no specialized arbitration board or committee for intellectual property in China. With the amendments to the Patent Law, besides reward and remuneration, additional modes including equity, options and dividends are introduced for benefit-sharing between an employee and an employer; however, it is unclear how disputes would be solved under the newly adopted modes in the future. There is, accordingly, an imperative to introduce more diverse and consolidated mechanisms for resolving such disputes and achieving a harmonious employment relationship.

This article begins with an analysis of the practice in civil law jurisdictions such as Germany and France and common law jurisdictions which have established time-honored dispute resolution mechanisms for employee inventions. Drawing on the practice in these jurisdictions, as well as recent legislative amendments, patent-filing trends and patent enforcement in China, this article then offers suggestions for improvement.

2 Dispute Resolution Mechanisms for Employee Inventions in Representative Civil Law Jurisdictions

Germany and France are civil law jurisdictions similar to China, and both of these countries have established the mechanisms for employee inventions for several decades. We will analyze the German dispute-resolution system for employee inventions (hereinafter referred to as the "German system") from the perspective of legal provisions on employee inventions, proceedings available for resolving such disputes and recent statistical data. Further, a brief introduction will be made on the resolution mechanism for disputes on employee inventions in France (hereinafter referred to as the "French system"), which enjoys similarity to the German system to some extent.

2.1 German System

Germany's Patent Act and Employee Inventions Act established the country's legal framework for employee inventions, with the former prescribing original ownership to a patent10. The Employee Inventions Act came into effect in 1957, covering not only inventions but also technical improvement proposals made by employees in private employment and public service, and by civil servants and members of the armed forces11. Further, the Employee Inventions Act also governs dispute resolution proceedings between employers and employees. Specifically, it provides a dual dispute-resolution mechanism consisting of arbitration proceedings and judicial proceedings.

2.1.1 Arbitration Proceedings

Aiming to reduce the employment relationship burden when differences of opinion are settled in court, arbitration enables out-of-court dispute settlement. Issues regulated by the Employee Inventions Act are applicable for arbitration proceedings conducted at the Arbitration Board which was established in 1957 and set in the German Patent and Trade Mark Office (DPMA) of the Arbitration Board under the Employee Inventions Act12. The Arbitration Board consists of a three-member panel: a chairman who is a legal expert and two assessors. The chairman shall be qualified for judicial office under the Law on the Judiciary, and is appointed by the Federal Minister of Justice at the beginning of each calendar year. The assessors need to possess special knowledge in the technical field to which the invention or proposal for technical improvement applies, and are appointed by the President of DPMA on a case-by-case basis. Assessors are generally DPMA patent examiners specializing in the relevant technological field. The Arbitration Board is under the supervision of the chairman, who, in turn, comes under the supervision of the Federal Minister of Justice.

Proceedings of arbitration: In all disputes arising from the Employee Inventions Act, a request for arbitration may be filed in writing with the Arbitration Board at any time13 free of charge14. The request may be submitted by an employee, an employer or jointly by both parties. It needs to be self-contained, and cover at least the claim(s) and the disputed issue(s)15. Arbitration is generally conducted in writing. The parties involved are required to describe the facts of the case and present counter-claims to the other side's synopsis if in disagreement. The Arbitration Board will only conduct oral hearings in extraordinary circumstances, when and if it deems such a procedure necessary. Proceedings before the Arbitration Board are confidential and held in camera. Non-participating parties are therefore excluded from inspecting the submissions or settlement proposals. Employers, employees and their representatives may nonetheless have a legitimate interest in the Arbitration Board's past decisions. Since its establishment in 1957, the Arbitration Board has regularly published selected anonymized decisions, searchable on the DPMA website16. The selected decisions lay out legal provisions and related facts, but omit any information which may identify the parties. Such decisions offer some guidance to the public.

Regarding outcomes of arbitration proceedings17, the Arbitration Board's decisions are rendered by the majority, with several outcomes including settlement being possible18. The Arbitration Board provides the parties with a settlement proposal, justified and signed by all its members19. In the absence of a written objection received within one month of the proposal being notified, this document is deemed to have been adopted and a corresponding agreement reached20. A party prevented by force majeure from filing oppositions in time may be reinstated on a petition, submitted in writing to the Arbitration Board within one month of the obstacle being removed.21 A one-year limit following notification of the proposed agreement applies, after which the re-establishment of rights can no longer be requested and the opposition may no longer be formulated22. The Arbitration Board decides on the petition for reinstatement, however, this decision may be immediately appealed, in accordance with the provisions of the Code of Civil Procedure, to the court in the place of the petitioner's residence23.

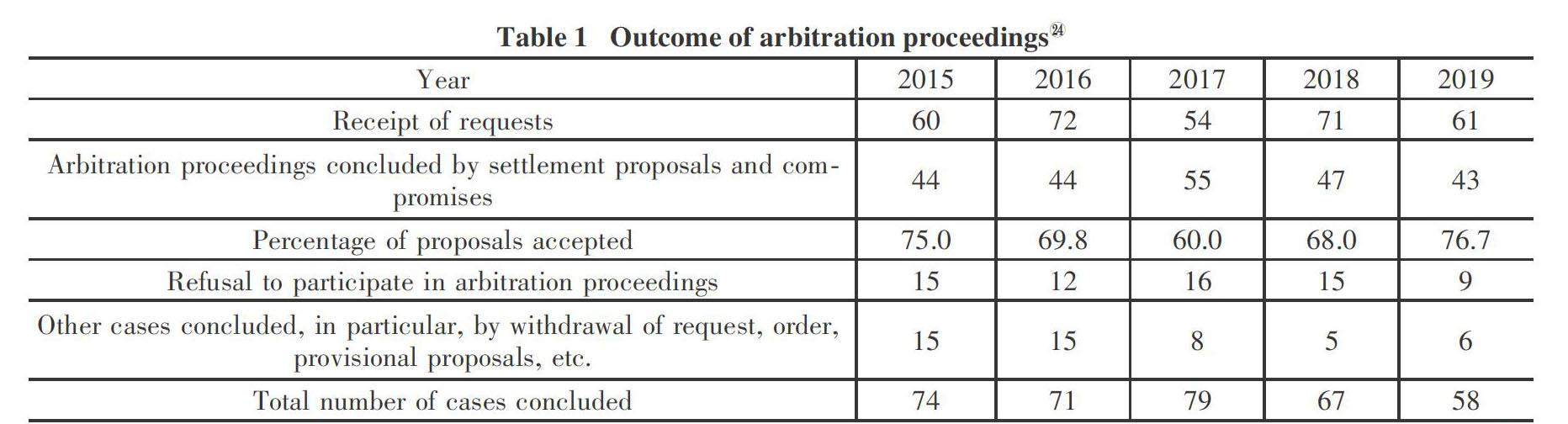

In Germany, the effectiveness of arbitration in resolving disputes arising out of employee inventions has withstood the test of time. Exemplary data in recent years are shown in Table 1, which demonstrates the results of arbitration over the past five years.

As seen from Table 1, the Arbitration Board receives dozens of disputes each year, with a majority reaching the settlement. Proceedings before the Arbitration Board maintain good employee relations, ensure legal concord and prevent court proceedings to some extent.

2.1.2 Judicial Proceedings

The other method of dispute resolution under the Employee Inventions Act is judicial proceedings. The prerequisite is generally that proceedings have been held before the Arbitration Board25. This does not apply where, for instance, arbitration is excluded by agreement, six months have elapsed since the request had been filed with the Arbitration Board, or the employee had left the employer's enterprise26. For all disputes concerning employee inventions, except those relating exclusively to claims for the performance of a declared or fixed remuneration, the jurisdiction rests with the courts having jurisdiction in patent litigation, irrespective of the value involved27. The rules on the procedure in patent disputes applies28.

As we may see above, Germany operates a dual arbitration-adjudication system, where the former is generally a prerequisite for the latter. Both proceedings are applicable for disputes under the Employee Inventions Act. In practice, a majority of disputes are settled at arbitration proceedings.

2.2 French System

Similar to Germany, France also operates a dual dispute resolution system for service-invention related disputes29.

2.2.1 Conciliation

Either or both the employer or employee may apply for conciliation. Proceedings are dealt by the National Commission for Employee Inventions (CNIS) sitting at the National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI). The Commission generally consists of three members: a chairman, which is a magistrate, and representatives from the parties.

Proceedings of conciliation. Conciliation is initiated by way of a letter to a specified address30. Its contents specify: (1) the names and addresses of the parties; (2) the subject matter of the dispute, the arguments of the parties and all the elements that may be useful in resolving the dispute; (3) description of the invention in question, or the patent number if a patent has been filed; and (4) a copy of the declaration of invention31. Any document submitted to the Commission by one of the parties will be communicated to the other party, and thus the conciliation proceedings are "adversary"32. The conciliation proceedings will be finalized within 6 months upon receipt of the letter33.

Outcome of arbitration proceedings. Normally, arbitration yields two kinds of results. If the Commission succeeds in reconciling the two parties, such agreement is noted in its minutes. If it fails to reconcile the parties, the Commission drafts a "conciliation proposal", on which agreement may be reached unless one of the parties refers the matter to the Parisian High Court.

2.2.2 Judicial Proceedings

In parallel to the conciliation proceedings, judicial proceedings may also be selected for solving disputes relating to employee inventions. French practice differs from its German counterpart in that adjudication does not depend on a request for conciliation having previously been filed.

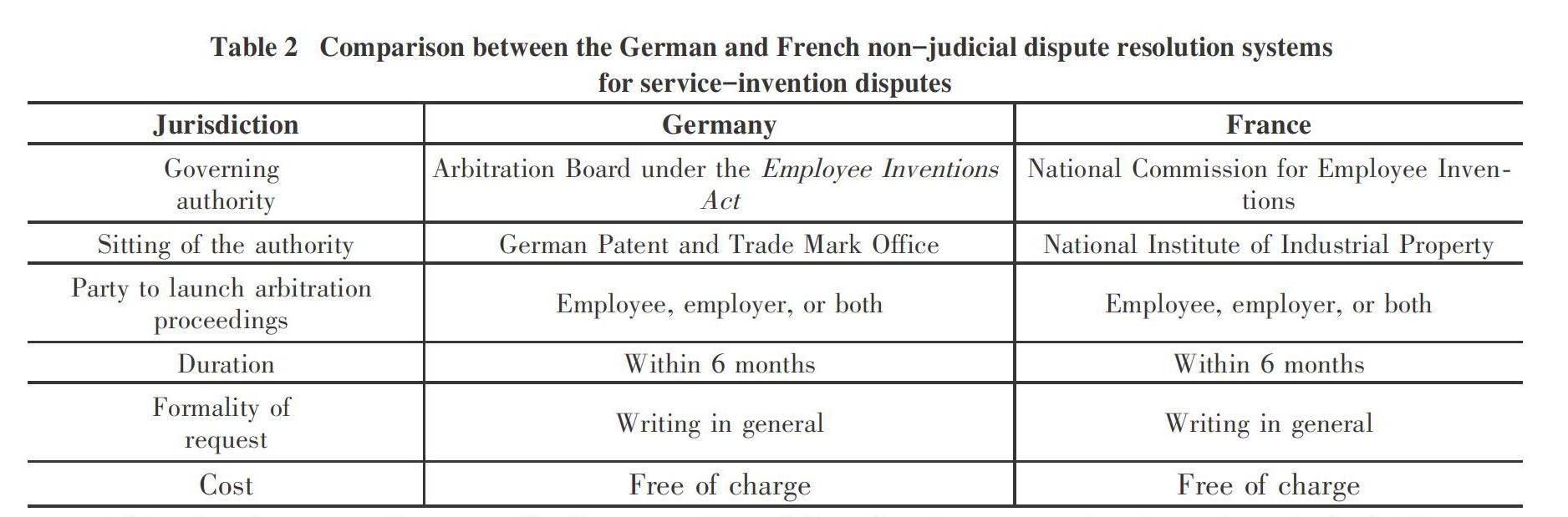

Emphasizing flexibility, the French system is simple, fast, and free of charge. As summarized in Table 2, many similarities exist between the French and German systems, particularly for the arbitration in Germany and conciliation in France.

Arbitration has served as an effective way of resolving disputes on service inventions in both Germany and France. Among the differences is the German system's requirement for arbitration before adjudication can be launched. In France, no such restriction exists.

3 Scenarios for Employees' Inventions in Representative Common Law Jurisdictions

The U.S. and the U.K. are representative common law jurisdictions. In the U.S., there is no explicit legal requirement for remuneration for employees' inventions. In practice, material or non-material benefits may be awarded to the employees, for instance, reward for the inventions within a company, recognition in company newsletter, plaques, among others. Further, the reward for employees is often embodied in the process of technology transfer. Different from the U.S., employees' inventions and compensation therefor are prescribed in the Patents Act (1977) in the U.K..

3.1 The U.S. System

The invention activities in the United States have experienced the transformation from individual creativity to organized innovation[6]. Upon study of the changes in the ownership of inventions made during employment in American society, it was found that in the early 19th century, employees had all the rights; in the late 19th century, employees still had all the rights, but employers usually got the license to use inventions; and in the early 20th century, employers had more rights than employees[7]. During this period, shop right also evolved from a simple license to a mechanism for balancing the rights of employers and employees. Although the U.S. patent law legal system does not directly provide for employees' inventions and the reward or remuneration therefor, it stipulates that the applicant for patent be the inventor(s), and employees retain significant rights to their ideas if they were directly connected to patented inventions. Many American companies have set up an internal reward mechanism for such inventions. Further, the reward for the patented inventions of the employees in the U.S. is often reflected in the process of technology transfer. Some scholars also suggest that, to motivate the employees in the U.S., a patent right be owned by both the employer and the employee before the expiration of a patent[8].

From the above, it can be seen that the U.S. does not directly regulate employees' inventions at the legislative level, but through the internal management and regulations of some enterprises or institutions, it provides employees with the opportunity to obtain rewards. The U.S. system offers flexibility to the enterprises or institutions on the rewards, which may be favorable for the management thereof and the development of technology in the U.S., and the U.S. has been maintaining a relatively leading level of technology innovation.

3.2 The U.K. System

The U.K. has a long history of intellectual property protection, and experiences thereof are also worth noting[9]. The resolution mechanism for disputes on employees' inventions, particularly award for employees' inventions, covers administrative and judicial proceedings, as demonstrated in the Patents Act (1977). In the administrative proceedings, an employee may file a request to the Comptroller of the Patent Office for compensation. In the judicial proceedings, a claim may be filed to the court. Where certain conditions are met, the invention or the patent for it is of outstanding benefit to the employer and an award is therefore "just", the court or the Comptroller may award the employee such compensation34. Moreover, the administrative procedure is not the prerequisite for the judicial procedure. In the case that the Patent Office considers it more appropriate for the court to deal with the relevant dispute, the applicant's request may be rejected35.

The resolution mechanism for disputes on employees' inventions is reflected in case laws. Even though the provisions on service inventions were prescribed in Patents Act 1977 in the 1970s, the court first ruled in 2009 to award compensation for employees' inventions in the case Kelly & Anor v GE Healthcare Ltd[10], which has milestone significance. On the one hand, the relevant terms of the Patent Act were interpreted in this case, including "outstanding benefit," "inventions belonging to the employer," which makes the understanding on relevant clauses of the Patent Acts much clearer. On the other hand, in the case, the result was favorable to the two inventors (plaintiffs) who received high compensation. Dr. Duncan Kelly and Dr. Kwok Wai (Ray) Chiu were two research scientists at Amersham International Plc (Amersham). Two patents were involved in the case, with Dr. Kelly and Dr. Chiu as inventors. The patents were considered to have been of outstanding benefit to Amersham, and ?50 million was taken as the value of the patents by the court. The inventor Dr. Kelly received ?1 million and the other inventor Dr. Chiu received ?500,000.

Another influencing case in recent years is Shanks v. Unilever Plc and others. In this case, Professor Shanks firstly made his application for compensation to the Patent Office in 2006. The hearing was held in 2012 and lasted for nine days. In 2013, the hearing officer acting for the Comptroller made a decision and found that the benefit provided by the Shanks patents fell short of being outstanding regarding the size and nature of Unilever's business. Professor Shanks appealed to the High Court against the hearing officer's decision. The High Court dismissed the appeal, holding that the hearing officer had made no error of principle in finding that the Shanks patents were not of outstanding benefit to Unilever [11]. Professor shanks filed a lawsuit in court, and the court of first instance upheld the decision of the patent office. Professor shanks further appealed to the Court of Appeal, and the appeal was also dismissed[12]. Finally, the Supreme Court made a decision[13] which overturned the decisions of the Comptroller, the court of first instance, and the court of second instance, and concluded that the Shanks patents were of outstanding benefit and Professor Shanks was entitled to a fair share of that benefit amounting to ?2 million.

Accordingly, in the U.K., if an invention or the patent for it, or the combination of thereof is of outstanding benefit to the employer, the inventor may be awarded with a high compensation.

4 Analysis on Resolution Mechanisms for Disputes on Employees' Inventions in Overseas Jurisdictions

The resolution mechanisms for disputes on employees' inventions are enumerated in representative civil law jurisdictions and common law jurisdictions. It can be seen that the mechanisms in different jurisdictions have different characteristics.

For the German system, all the disputes under Employee Inventions Act can be pursued for seeking resolution via arbitration proceedings or judicial proceedings. The Employee Inventions Act set an "umbrella" and legal foundation for resolving such disputes at both substantive and procedural levels. In practice, the remuneration calculation may be referred to the Guidelines on the compensation for employee inventions, which provides detailed formulas and factors to be taken into account when determining remuneration for employee inventions in different scenarios, e.g., transfer of rights, licensing. Accordingly, when disputes arise, an employer and employee may find clear guidance by referring to the Employee Inventions Act and Guidelines on the compensation for employee inventions. Further, the arbitration proceedings are conducted at a specialized board, i.e., Arbitration Board under the Employee Inventions Act. With the legal and technical experts in the Arbitration Board, the compensation could be determined with some reasonable expectation, considering the availability of the Guidelines and the selected exemplary cases. And as shown in Table 1 above, disputes can be settled in an efficient way.

As demonstrated in Table 2 above, the French system shares similarity to the German system. Both the arbitration proceedings in the German system and the conciliation proceedings in the French system are generally held in a written formality and in a confidential way, which on the one hand favors the employees regarding confidentiality and on the other hand benefits the employers for not necessarily disclosing business information thereof to the public. A specialized committee is available for conciliation in the French system, so as to settle disputes on employee inventions amicably. One difference is that, unlike the German system, the conciliation proceeding is not a prerequisite for the initiation of a judicial proceeding. Another difference lies in the absence of Guidelines on the compensation for employee inventions in France. But factors that can be considered are enumerated in the French Intellectual Property Code36, which are taken into account during conciliation and judicial proceedings. The French system advances the effective and efficient resolution on such disputes amicably.

In the U.K. system, different from the German and French systems, there is no specialized board for resolving disputes on employees' inventions. The request for compensation can be filed either to the Patent Office or to the court. Unfortunately, the proceedings at the Patent Office may last for a long time. From the case Shanks v. Unilever as described above, it can be seen that the request was filed in 2006 and the case was heard and decided at the Patent Office several years later. This may be a disadvantage for the employees to claim rights at an early stage after an invention or patent has been commercialized. But the advantage is at least that, if the invention or the patent for it, or the combination of thereof is of outstanding benefit to the employer, the inventor may be awarded with a high compensation. Another advantage is that the request could be filed even in a short time before the expiration of a patent37.

Last but not least, the U.S. system is unique and different from the above-mentioned systems in that there is no requirement for remuneration for employees' inventions at the legislative level. This may originate in Article I Section 8 of the Constitution of the U.S., which secures inventors the exclusive right to their discoveries. Such exclusive right of inventors at the Constitution level would naturally lead entities including companies and institutions to reward inventors in order to smooth the assignment of rights from employees to employers. Further, no mandatory requirement on how to reward and remunerate inventors in turn allows employers to offer rewards to employees in monetary or non-monetary ways, which provides flexibility benefit for the entities. It is believed that such a unique system may contribute to the leading level in global technology innovation of the U.S..

In view of the practices in the civil law and common law jurisdictions, discussion will be made on current Chinese mechanisms in the section below, and suggestions are opined accordingly.

5 Discussions and Suggestions

As addressed in the Introduction section, the number of cases concerning service inventions has exploded compared to ten years ago in China. This places an increasingly heavy burden on courts, which frustrates the parties' quest for expeditious results. As well, settlement is often not easy to be reached via mediation. China needs therefore to explore more diversified dispute resolution mechanisms for service inventions. The practice in other jurisdictions will provide a basis for discussion and offering suggestions.

5.1 Potential Issues with Current Dispute Resolution Mechanisms for Service Inventions

Civil law jurisdictions operate diverse dispute resolution mechanisms for employee inventions. For instance, China offers arbitration, mediation and adjudication. This section addresses the pros and cons of each.

5.1.1 Arbitration Proceedings

Disputes over service inventions are not explicitly excluded from eligibility for arbitration under China's Arbitration Law, Article 2 of which states that "[d]isputes over contracts, property rights and interests between citizens, legal persons and other organizations as equal subjects of law may be submitted to arbitration." The parties to such disputes, generally an employee and an employer, are equal legal subjects. Such disputes may relate to either contracts or property rights and interests, and fall outside the Law's exceptions. Article 3 outlines disputes which are ineligible for arbitration, namely those concerning marriage, adoption, guardianship, child maintenance and inheritance. Administrative disputes falling within the jurisdiction of relevant administrative organizations according to the law are also excluded. It would seem that disputes over service inventions generally do not fall within such categories of ineligibility.

Some employees may attempt labor arbitration, yet disputes over service inventions may be excluded from such proceedings under the Law for the Mediation and Arbitration of Labor Disputes38. It is debatable whether disputes over service inventions, in particular those involving remuneration for service inventions, are labor disputes. This is explicitly excluded by some provinces in practice. For instance, in Jiangsu Province, it is clearly stated that disputes between employers and employees, due to the distribution of interests in intellectual property rights, are not labor disputes39. Considering the difference between the remuneration for service inventions and labor remuneration, and that technical knowledge is often necessary for resolving such disputes, it is not advised to resolve them via labor arbitration[14]. In civil law jurisdictions such as Germany and France, such disputes are not governed by labor arbitration proceedings.

From the above, it can be seen that labor arbitration may be less than ideal or entirely inapplicable. Alternative proceedings may serve to resolve such disputes effectively. We will discuss this in more detail below.

5.1.2 Mediation Proceedings

As previously discussed, although Germany and France do not provide for mediation, some scholars believe that it does mirror mediation to an extent[15]. Such views consider that the Arbitration Board merely issues non-binding settlement proposals, leaving the parties free to resort to other proceedings.

Chinese mediation proceedings are relatively flexible, making possible an amicable settlement. In practice, some disputes on service inventions were indeed resolved via mediation, the legal basis for which is found in the Measures for Administrative Patent Enforcement40. 2015 saw the Measures being amended41.

Some disputes were successfully resolved via mediation. In 2017, it was reported that the Intellectual Property Office of Pudong New District mediated between a science and technology company in Shanghai and its employee Mr. Zheng, reaching an agreement on reward and remuneration disputes over 10 service-invention patents42. This was the first successfully-mediated administrative case concerning disputes over service inventions, being settled on oral hearings, cross-examination, inquiry and statement.

The China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) recently issued its Guidelines for Administrative Mediation Concerning Patent Disputes in July 2020 (hereinafter referred to as "the Guidelines"). Article 2(ii) and Article 3(iii) of the Guidelines both provide that administrative mediation is voluntary and non-binding, meaning that if one party objects to mediation or the parties fail to reach a mediation agreement, they may resort to alternative proceedings. Further, administration mediation is inapplicable if a judicial proceeding has been initiated, if the parties agree on arbitration or if arbitration proceedings have been initiated.

The Guidelines enumerates the types of the patent disputes to which administrative mediation applies43. For service inventions, disputes on ownership, reward and remuneration are covered. Where the facts are clear and the circumstances simple, one mediator will suffice; mediation in other circumstances may be overseen by a collegial group composed of three mediators44. The Guidelines provide detailed procedures for mediation and different scenarios, serving as a practical compass in pursuing mediation.

The mediation as outlined in the Guidelines shares some degree of similarity with the arbitration practiced in civil law jurisdictions, insofar as the effect of mediation and the composition of the mediation panel are concerned. Yet there still are differences. For instance, the arbitration in Germany and the conciliation in France are conducted by a specialized board or commission which sits at the national intellectual property authority. In contrast, administrative mediation on patent disputes in China is conducted at the regional administrative authority for patent affairs instead of the CNIPA. Mediation may offer the additional advantage of efficiency. The authority must finalize mediation within two months following the case being placed on file45. In some special circumstances, a maximum one-month extension is available upon request.

Mediation may serve as an efficient alternative dispute resolution mechanism for patent disputes, as it does not place strictures upon the types of eligible dispute. It could be objected, however, that because mediation is non-binding, enforceability of the agreement is cause for concern.

5.1.3 Judicial Proceedings

In China, a judicial proceeding is an important means of resolving disputes over service inventions, bringing disadvantages as previously discussed. Firstly, an employee may find it burdensome to initiate and pursue judicial proceedings, or may find the costs prohibitive. This may reach tens of thousands RMB (excluding attorney fees or notarization fees), especially when the case is appealed to a higher court. Secondly, the parties do not have equal access to evidence. It is normally more readily accessible to an employer, while an employee may encounter not insignificant hurdles in gathering evidence. Thirdly, contrary to the confidential nature of arbitration or mediation, adjudication is often held in public, with decisions generally published. This may be deleterious to an employer or employee's reputation. There is a further risk of confidential or sensitive information being leaked to the general public or competitors. Last but not least, judicial proceedings may adversely affect the harmonious employer-employee relationship.

Despite the preference of jurisdictions such as Germany and France for an out-of-court settlement, they nevertheless offer adjudication, which is binding upon and the last recourse available to the parties. In China, the Supreme People's Court provides that courts are competent to rule on "disputes concerning the reward and remuneration of service inventions." Courts are further competent to rule on disputes over ownership of patent applications or patents, potentially covering those generated and filed during employment.

It would appear that courts are competent in multiple issues on service inventions. Some issues on service inventions may, unfortunately, fall outside the province of the courts. For instance, if one made an invention under employment, and a dispute arises over whether it is a service invention or not, and a further dispute on whether to file for a patent application or not, it is insufficiently clear whether such issues are amenable to adjudication. Further, amendments to the Patent Law and current practice hint at diverse other means, beyond reward and remuneration, of advancing service inventions and enabling employees to reasonably share in the profits of innovation. One such possibility is options. Disputes on such means may also require adjudication. Therefore, it is advisable to bring new types of disputes over service inventions under the courts' competence, such as those arising from technical or economic development, or legislative amendments.

5.2 Proposals on Diversification of Resolution Mechanism in China

5.2.1 Proposal to Establish Specialized Arbitration Boards or Commissions

As discussed above and as prescribed in the Guidelines, arbitration is one of the dispute resolution mechanisms for patent disputes, including service-invention patents. Despite this, both theoretical and practical ambiguity linger over whether labor arbitration is applicable in such disputes. Even though service inventions are generated under the employment relationship, the patent law and the labor law provide for different legal bases that, combined with the requirement for technical expertise, makes it eminently sensible to exclude labor arbitration from the dispute resolution mechanisms for service-invention patents. Were labor arbitration to be applicable, it would conflict with judicial proceedings, since labor arbitration is a prerequisite for the lodging of judicial proceedings. Hence, it is proposed that, in order to address such issues, specialized arbitration boards or commissions be established.

As previously described, civil law jurisdictions such as Germany and France establish specialized arbitration boards or commissions at their national intellectual property authorities. For decades, they have operated smoothly and efficiently in resolving disputes out-of-court. Other European countries such as the Netherlands and Finland also have arbitration boards or commissions. China could emulate such practice to reduce the burden on judicial resources and to maintain a harmonious employment relationship. The sheer amount of patent applications lodged annually in China and its expansive territory militates against the establishment of such boards at the CNIPA-level. Instead, they may be established in cities with a high frequency of disputes.

Disputes are currently concentrated in economically active regions such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, Jiangsu and Zhejiang. The key issues touch upon ownership of patent (application) rights as well as reward and remuneration for service inventions46. The establishment of specialized arbitration boards in these cities and provinces would accordingly be propitious. Major cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, which already have intellectual property courts, could conceivably play host to the arbitration boards. The arbitration boards may sit in the intellectual property courts of these cities, being composed of three members: a chairperson who is a legal expert, and one representative from each of employer and employee. Technical experts may be brought on-board where reward or remuneration is at issue. Further, the legal effect of specialized intellectual property arbitration would need to be differentiated from mediation in order to underscore the difference with administrative mediation.

5.2.2 Proposal to Consolidate Mediation, Arbitration and Judicial Proceedings

The systematic resolution of disputes over service inventions requires the effective unification of the scope for mediation, arbitration and judicial proceedings.

First, it is advised to unify the scope for disputes on service inventions in different proceedings. Germany, like France, generally permits all disputes under the Employee Inventions Act to be amenable to arbitration and adjudication. Current Chinese practice set forth in the Guidelines or Interpretation is rather less generous. With the development of law and technology, this means that some disputes may not be covered. One solution would be to unify the scope for different proceedings, by making disputes on service inventions arising from the Patent Law and the Implementing Regulations thereof eligible for currently available proceedings.

Second, consolidate multiple proceedings. To obviate potential ambiguities in practice, proceedings should be consolidated. As previously stated, arbitration serves as a precondition to adjudication in Germany. No such requirement exists in France, where a party may freely elect either arbitration or judicial proceedings. To efficiently resolve disputes over service inventions and to avoid potential conflict with adjudication, the French mechanism is preferred. Once a party makes an election as to the type of proceeding, it is disallowed from simultaneously pursuing the other. This avoids wastage of administrative or judicial resources, and obviates potentially inconsistent outcomes in parallel proceedings. The proceedings' precedence also needs to be taken into account. If a party initially elects mediation but fails to reach an agreement, they may elect other proceedings to settle the disputes, as prescribed in the Guidelines. However, if arbitration or judicial proceedings have been initiated, it would be unfeasible to pursue mediation. If a party elects to begin with the arbitration, mediation will be similarly excluded. The party may still appeal to the court, even though arbitration is not a precondition for filing court proceedings.

5.2.3 Others

The dispute resolution mechanisms in Germany, France and the U.K. may find basis from intellectual property laws (e.g., the Employee Inventions Act in Germany, the French Intellectual Property Code in France and the Patent Act in the U.K.) As discussed in the Introduction section initially, the Draft Regulations on Service Inventions (Draft for Review) in China has not come into effect. It is suggested the legislation on service inventions be expedited, with resolution mechanisms included therein. As such, the multiple proceedings may be better coordinated at the legislative level.

Further, considering the diverse desires of different employees in modern society, it would also be advisable to adopt different ways to award employees, like the options available in the U.S.. This may attribute flexibility to the management of the employers, motivate employees in the long run and encourage innovation in a developmental way.

6 Conclusion

In an innovation-oriented country, such as China, there have been an increase in service-invention patents. Employees behind service inventions have contributed significantly to technological and economic developments, which in turn leads to a concomitant increase in related disputes. Encouraging innovation is critical. So is the negotiation of a balance of interests between employers and employees, and the maintenance of harmonious employment relations. Drawing on established systems in overseas jurisdictions, dispute resolution mechanisms such as specialized intellectual property arbitration may achieve amicable dispute settlement. Effective and efficient resolution of disputes surrounding service inventions should see the establishment of specialized arbitration boards or commissions in cities where intellectual property courts are located. Moreover, the coordination of mediation, arbitration and judicial proceedings is advised at legislative and practical levels, so that they work collectively towards smooth and effective dispute resolution.

References:

[1] Michael Trimborn. Employees' Inventions in Germany: A Handbook for International Businesses[M]. Publisher: Kluwer Law International, 2009.

[2] Sebastian Wündisch. Employee-inventors Compensation in Germany—Burden or Incentive? Social Science Electronic Publishing. Available at www.ssrn.com. 2017.

[3] He Min. , Zhang Haoze. Research on the Application of Co-ownership by Shares in Employee Invention[J]. Science, Technology and Law, 2018(5): 1-6.

[4] Liu Qiang. , Chen Hui. An Empirical Study of Judicial Reward for Service Invention[J]. Science, Technology and Law, 2017(3): 25-38.

[5] Intellectual Property Tribunal of the Supreme People's Court. Annual Report of Intellectual Property Tribunal of the Supreme People's Court (2019)[M]. Beijing: People's Court Press, 2020.

[6] Wang Zhongyuan. Evolution of the U.S. Service Invention System and Implications for China[J]. Journal of Anhui University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), 2012, 36(1): 135-140.

[7] Catherin L Fisk. Removing the "Fuel of Interest" from the "Fire of Genius": Law and the Employee-Inventor, 1830-1930[J]. University of Chicago Law Review, 1998, 65(4): 1127-1198.

[8] Wang Yucheng. A Statutory Patent Reversion Period May End the Debate on Employee Inventions[J]. John Marshall Law Review, 2018, 51(3): 675-714.

[9] Zhu Nan. The Change and Evaluation of the Protection System of Industrial Designs in the U.K.[J]. Journal of Shanghai University of Political Science and Law, 2016, 31(3): 110-118.

[10] Kelly & Anor v GE Healthcare Ltd [2009] EWHC 181 (Pat).

[11] Shanks v Unilever Plc & Ors [2014] EWHC 1647 (Pat).

[12] Shanks v Unilever Plc & Ors [2017] EWCA Civ 2.

[13] Shanks v Unilever [2019] UKSC 45.

[14] Zhe Dai. L'amélioration du règlement des litiges relatifs aux inventions de salariés en Chine. Revue Francophone de la Propriété Intellectuelle[J]. 2020(10): 37-53.

[15] Ge Jiang. Empirical Study of the German Regulation Regime of Service Inventions[J]. Tsinghua Intellectual Property Review. 2017(1):95-111.

摘 要:中國职务发明数量的增长以及职务发明纠纷的增加引起了各界的广泛关注,如何构建有效的纠纷解决机制成为了一个十分重要的议题。通过分析以德国和法国为代表的大陆法系国家以及以美国和英国为代表的英美法系国家的相关纠纷解决机制,并将其与中国当前实践进行比较,(本文认为)有效的纠纷解决机制应致力于两方面努力。一方面,在设有知识产权法院的城市设立解决职务发明纠纷的专门委员会来专门处理职务发明纠纷。另一方面,在实体和程序上协同调解、仲裁及诉讼程序,从而使这些机制能够共同实现职务发明纠纷的有效解决。在参照《专利法》第四次修改内容和《专利纠纷行政调解指南》的基础上,将中国实践中的各种职务发明纠纷解决机制相协调,这有利于激励科技创新,平衡雇主与雇员的利益,进而有助于将中国建设成为创新型国家。

关键词:职务发明;雇员发明;仲裁;诉讼;专利纠纷