Dancing and Drawing in Trisha Brown’s Works:A Conversation Between Choreography and Visual Art

2021-07-23LuShirleyDai

Lu Shirley Dai

[Abstract]This paper explores the connections between choreographic approaches and creative processes in dance and visual art.It develops from a postmodern and historical foundation and looks at choreographer Trisha Brown’s drawing and dancing in the 1970s,a crucial period when Brown investigated fundamental questions about choreography.It was through her drawing and choreography that Brown was able to examine structure from both choreographic and visual perspectives.After an introduction,Part 1 uses Wassily Kandinsky’s theory of line to analyze Brown’s 1973 linear drawings as well as her notion of the body-making line in space.Part 2 compares Brown’s Locus (1975) with conceptual artist Sol LeWitt’s sculpture Incomplete Open Cubes (1974).Both Brown and LeWitt emphasize the conceptual idea behind a work of art,and both adopt the cubic form as a visual strategy to actualize their conceptual ideas.By analyzing Brown’s dancing and drawing in the discourse of dance history and art history,this paper emphasizes that Brown’s intellectual inquiry as an artist contributes to the ongoing interdisciplinary conversation between choreography and visual art in the 20th and the 21st century.

[Keywords]Trisha Brown,structure,dancing and drawing,choreography,visual art

Introduction

This paper aims to explore creative processes in choreography and visual art by looking at the interactions between dancing and drawing,two forms of expression innate in our body and mind.It takes form in the examination of Trisha Brown’s drawings and dancing works of the 1970s when she negotiated with history while explaining and defining her individual artistic voice.

Trisha Brown is an interdisciplinary artist.Her affection and dedication to choreography and visual art come not only from her personal interest in both art forms but also from the collective artistic condition of the contemporary art community.

Trisha Brown was one of the young artists active in both Robert Dunn’s workshop and the Fluxus group at 80 Wooster Street in the early 1960s.In these two groups,there was a shared postmodern ideology that propelled artists of the 1960s to invent new forms and styles and establish an aesthetic that was objective and interdisciplinary.Because of the strong influence of the interdisciplinary approach in the Judson and Fluxus groups,Brown,not unexpectedly,developed an interest in visual art and began to incorporate drawing in her creative process.

This thesis project develops from a postmodern historical foundation and looks at Brown’s drawing and dancing in the 1970s,a crucial period when Brown constantly investigated fundamental questions about choreography.It was through her drawing and choreography that Brown was able to examine structure from both choreographic and visual perspectives.Part 1 of this paper as follows uses Wassily Kandinsky’s theory of line to analyze Brown’s 1973 linear drawings as well as her notion of the body-making line in space.Part 2 compares Brown’sLocus(1975) with conceptual artist Sol LeWitt’s sculptureIncomplete Open Cubes(1974).Both Brown and LeWitt emphasize the conceptual idea behind a work of art,and both adopt the cubic form as a visual strategy to actualize their conceptual ideas.

Treating the body as line on paper and in space

In the early stage of her artistic career,Trisha Brown utilized drawing as a tool that helped her build up a movement vocabulary and develop a system to generate movements in dance.In the early 1970s,Trisha Brown was propelled by an urgency for movement exploration.

In her conversation with Klaus Kertess,Brown said,“I was looking for a vocabulary that I thought was non-virtuosic and had a significance to me,wanting to work abstractly and putting in the search for a new vocabulary.”[1]At the same time,she was negotiating with the legacy of Judson and finding her own voice as an individual choreographer.

With such eagerness to explore movement,Brown sought to make the intentionality clear while avoiding“arbitrariness.” According to Susan Rosenberg,Brown declared that “to make a movement,to make a dance,to choose a gesture ...I have to have a reason to do it.It’s just as simple as that ...I can’t do anything that has no logic to it.”[2]38

With the intention of “wanting to work abstractly,”Brown turned to drawing.Beginning in 1973 (the earliest year when Brown’s drawings were exhibited to the public),she had used drawings as notations that visually tracked and represented her movements.Yet,unlike choreographers who returned to drawing after developing dance materials,creating a visual record that complemented movements and choreography,Brown reversed the process.She treated drawing as a relatively independent art form,which was developed not only parallel to the choreographic process but was also built even before the creation of physical movements.Brown’s use of dance notation was highly influenced by Robert Dunn’s interpretation of Labanotation.For Dunn,“Laban’s notational system (has) the dual purpose of documentation and generation,the space between recording movement and implying.”[3]21With respect to Labanotation,he suggested “(the dance-writing) create(s)a compositional tool,putting notation before movement ...to use graphic,or written,inscriptions and then to generate activities.Graphic notation is a way of inventing dance.”[3]21

The key idea in Dunn’s interpretation of Laban’s notational system was its potentiality to generate movements.Through applying Dunn’s method to her drawing,Brown worked with line as a rudimentary element that not only led her to a series of geometric and spatial investigations,but also eventually inspired and initiated a movement quality that Brown transferred onto a physical dancing body.In the early 1970s,Brown had penetrated the essentiality of line and the connection between dance and drawing through line.It was also by virtue of the understanding and use of line both in drawing and in her choreography that Brown generated abstract dance movements.

The history of line drawing can be explained through works by many artists.Wassily Kandinsky,for instance,not only regarded line as an essential constituent in drawing practice,but also analyzed its geometry theoretically.Kandinsky was an influential teacher at the Bauhaus in the 1920s.According to art scholar Susan Funkenstein,Kandinsky and his fellow artists shared a collective modernist aesthetic.“The Bauhaus endorsed artistic abstraction,in which the identifiable figurative subject matter was minimized or even obliterated.Instead,Bauhaus modernism put an emphasis on pictorial compositions of pure lines,blocks of color,and geometric shapes.”[4]390Beginning in the 1920s,Kandinsky studied line as one of the most basic components in painting not only to examine the underlying connections between line and other geometric elements,but also to discover its formal relationship with painting and other art forms.Such thinking is reflected in Kandinsky’s seminal writing,Point and Line to Plane,which first explains the formation of line:the “geometric line is an invisible thing.It is the track made by the moving point.”[5]57That is to say,the geometric line is a simple form created through the destruction of the repose of a static point and materialized through the point’s moving trace.

According to Kandinsky,the key element in the formation of line is movement,while the concept of movement addresses two important factors:“tension”and “direction.”[5]57Tension is the force inherent in the point.The action of releasing such energy,along with the application of external force,moves the point and forms a line.Various interactions and reinforcement of pressure create different forms of lines—straight,angular,and curved.Three typical straight lines are horizontal,vertical,and diagonal lines.[5]58While a straight line is formed through the application of one force,angular and curved lines are created when two forces take alternate or simultaneous actions.In juxtaposition to tension,direction also plays an important role in the formation of line as it determines where the force is leading.Combining the above two elements together,Kandinsky concludes that lines are “material results of movement in the form of tension and direction.”[5]58In other words,different levels of force and various directions performed by movement impact on the initial point and result in multiple forms of line.

The direction of movement provides the line with clarity and precision in its spatial orientations.The tension actualizes the expression of both the internal force in the line and the external force applied to the line.The aggregation of tension and direction results in movement that creates the line while the balance between the two forms a linear expression within the pictorial composition.Kandinsky’s study of the formation and qualitative characteristics of pure line enables him to define the geometric line as a basic formal element,whose simplicity achieves the quality of abstraction.The linear expressions in a pictorial composition realize harmony and balance.Kandinsky’s investigation therefore echoes the Bauhaus’s artistic objective,which asserts the primacy of abstraction and geometric simplicity in pictorial compositions.

This brief exploration of Kandinsky’s treatisePoint to Line to Planeprovides a theoretical approach to analyze Trisha Brown’s 1973 drawings.Brown’s investigation and use of line indicates a connection between the two artists’ understanding and interpretation of linear compositions.An early experiment,Brown’s 1973 drawings consist of a series of linear geometric forms.Simple yet complex,the basic elements running through the entire series of drawings are lines—vertical,horizontal,diagonal,and curved.Applying Kandinsky’s analysis of lines,one can see the formation of angular and curved lines as a result of the execution of tensions.The combination of these two forms of contrasting lines implies a group of dynamic actions and forces in the creative process.Though they are complicated as a mixture of various lines,Brown was able to discover the underlying transitional connections among all kinds of lines and the linear,geometric simplicity within such connections.In other words,in her 1973 drawings,Brown achieved abstraction through linear geometric constructs in the pictorial composition.

As Kandinsky emphasizes,lines are the “material results of movement in the form of tension and direction.”[5]58On one hand,movements create lines,a process in which“the leap out of the static into the dynamic occurs.”[5]57On the other hand,lines suggest movements.For example,“when a force comes without moving the point in any direction,the first type of line results; the initial direction remains unchanged and the line has the tendency to run in a straight course to infinity.”[5]57However,if multiple accumulated forces move the initial point into different directions,the straight line is then transformed into an angular or circular line.These two essential characteristics of movement—tension and direction—endow lines with the possibility of always shifting,extending,and changing directions,transforming them from simple,straight lines to more complex linear configurations.This potentiality for movement is inherent in the static lines and foreshadows the occurrence of dynamic changes in motion.

The ability of line to suggest movements is not limited to the movement within the drawing.It can also capture and represent the physical body’s movements in space.Not only did Kandinsky fully recognize the potentiality of the line for movement from his theoretical research,he also applied the analytical method both to his drawing practice and to his study of dance.The same year when Kandinsky completedPoint to Line to Plane,he published another essay “Dance Curve” (1926),in which he interpreted modern dancer Gret Palucca’s dance movements in line drawings.

In “Dance Curves,” Kandinsky presents four drawings in response to the photographs that capture Palucca’s stage dance movements.(Fig.1 shows one of the four photographs taken by Charlotte Rudolph.)Yet the drawings are not a realistic representation of the dancing figure,but a construct of linear elements that reveal an abstract form.Kandinsky gives an illustration of his drawing (Fig.2):“A long straight line,striving upward,supported upon a simple curve.Beginning at the bottom—foot; ending at the top—hand; both in the same direction.”[6]The drawing shows a clear,simple geometric form,in which angular and curved lines create a dynamic contrast and balanced tension.Kandinsky also emphasizes the direction of the lines in order to specify the trajectory and orientation of the movements.In this way,though developed from still photographs,the line drawing can represent not only the shape of the dancing body,but also its dynamism in motion.Kandinsky’s decision to render Palucca “as an amalgamation of simple lines” revealed his concern with abstraction and his intention to portray dance in “a clean precision style with non-sentimental,geometric,industrial forms.”[4]393—394

Fig.1 Charlotte Rudolph,Gret Palucca,1925[4]395

Fig.2 Wassily Kandinsky,“Dance Curves,” 1925[4]395

The drawings reveal several layers of Palucca and Kandinsky’s collaboration,as well as the interaction between the two art forms:dance and drawing.A modern dancer who had close relationships with avantgarde artists at the Bauhuas,Palucca embraced a nonsubjective artistic aesthetic and created dance movements that were geometric and abstract.Palucca’s movement style inspired Kandinsky to analyze her dance “as compositional arrangements of clean,crisp lines within pictorial planes.”[4]396That is to say,the simplicity and clarity of the line,along with its immense potentiality for movement,actualize dance through linear expressions while keeping and emphasizing the geometry and physicality of the dance movements.

Like Kandinsky and his drawings of Palucca in“Dance Curves,” Trisha Brown in her 1973 visual works initiated a conversation between dance and drawing.Favoring geometric lines,Brown achieved abstraction through linear and geometric patterns in composition.Yet unlike Kandinsky who explored “Palucca’s dancing as an expression of his theoretical principles based on abstraction” and drew from dance photographs,Brown integrated the two art forms and used drawing as a tool to generate new dance movements.[4]391

As Fig.3 shows,Brown first created a basic form—four squares inside a larger square in the 1973 drawings.This geometric structure was then used as an anchor that allowed for a series of spatial explorations of lines.During this process,Brown relied on both the consistency of the square and the sense of freedom offered by the drawing medium.Instead of insisting on keeping the compositional precision that Kandinsky emphasized in his drawings ofGret Palucca,Brown freed her drawing pen and allowed the line to perform its full potential.The result was a series of inventions enabled through the lines’ progression,following the same template,yet with different explorations of lines in the anchor square.Recognizing the line’s potentiality for movement,Brown was able to explore all kinds of possible transitions from one type of line to another and the potential directions and spatial orientations these lines create.Repetitions and variations were simultaneously involved in the creative process while new shapes would appear when curved lines were introduced into the square.

Fig.3 Trisha Brown, Untitled,1973[7]42

Fig.4 Trisha Brown,Untitled,1973[7]41

Furthermore,Brown relates the drawing to the human body.As she explains,“I had a notion that I could make an alphabet,four squares inside one larger square.And that shape became,in my imagination,related to the body.”[7]15The four squares become both a space that allows lines to make various transitions and movements and a dimension that exemplifies the range of motions the limbs are able to achieve.The essence is the geometric relationship between lines and lines,lines and the square,and the square and the outside space.Underscoring their potential for movements,lines become the “moving limbs” on paper while the direction and interaction of each line visualize the movements in space.As Brown explains,the drawings do not function as “dance grams”or a visual representation of the dancing figure.On the contrary,the lines in the drawings have the capacity to“sculpt space and a dimensionality that has a lot to do with the body.”[7]15

The 1973 drawing series and the process of drawing function as a mental activity that initiates and facilitates abstract thinking through linear compositions,an intellectual inquiry that explores the unseen beyond conventional choices by visualizing all the possibilities and spatial relationships,and an impulsive generator that not only creates a series of formal patterns as visual vocabularies,but also originates a geometric,linear movement quality that Brown would later incorporate into her choreography.Though the components of the drawings are purely straight,angular,curved lines in a square,the drawing’s openness and informality as well as the lines’potentiality for movements actualize Brown’s intention of the drawing—to explore the geometric relationships within the linear composition and abstraction,“to find out the vocabularies and to encompass it intellectually.”[7]15For Brown,the abstract,conceptual thinking processed in the mind,the experiments and explorations involved in the creative development,and the excitement and the unknown the action,are the essence of the integration of dance and drawing.The reciprocal relationship between drawing and choreography therefore corresponds to Robert Dunn’s approach to dance notation as both documentation and invention.

Parallel to her desire to explore and create vocabularies through drawing and thinking abstractly through geometric forms,Brown created a series of dances under the name ofAccumulationseries that were part of her experiment in building new movement vocabularies after Judson.In addition to experimenting with basic geometric shapes in her 1973 drawings,Brown “began an investigation (of movement) in a rudimentary,straightforward way.”[1]Inspired by her line drawings,she transferred the line on paper to the physical body,initiating what Helen Molesworth describes as “a treatment of the body as line in space.”[8]As Brown recalls in her writing,what she discovered were the most elementary movement vocabularies “stemmed from a deliberate investigation of the capabilities of the joints and spine,bend,straighten,and rotate.”[9]28In other words,all complicated movements of the limbs can be analyzed and articulated through the actions of bending,straightening,and rotating,an echo of Kandinsky’s concept of line’s two essential qualities:“tension” and “direction.” Bending and straightening result from engagement of muscle and tension at the joints while rotation enables changes in direction.The combination of these three movements thus creates the full range of motion for the limbs,implying the dynamism and energy created by tension and direction.Brown’s investigation of movement’s originality once again emphasizes her interest in abstraction,and in a basic anatomical analysis,limbs are likened to lines.

TheAccumulationseries extends the idea of linear expression into Brown’s choreography.InPrimary Accumulation(1972),Brown,wearing a long-sleeved white shirt and trousers,lies on the floor.Her torso is in a straight vertical line,her arms naturally relaxed at the side while her legs were slightly open to form a small V.This opening body position,or geometric shape—the simple vertical line of the torso and four relaxed limbs—is also the basic form to which Brown often refers as the piece progresses.Brown’s process of generating movements for the choreography was non-judgmental and experimental.She worked in “unaccented slow motion,observing the possibilities of the body,while passing through arm,leg,and torso alignments that were either parallel or perpendicular to the floor.”[9]28

The solo features Brown delineating “physical gesture through a logical,reductive analysis of the body’s anatomical functioning and an additive organization.”[2]38The title suggests that the movements are iterations of small linear gestures that begin with the limbs and gradually involve the performance of the whole body.In her neutral starting position,Brown first flexes her right elbow up to a vertical line,perpendicular to the floor.Then,returning to the original position,she raises the left arm straight to the ceiling,forming a straight vertical line.Keeping a balanced energy and steady rhythm,Brown continues to add new gestures to the old ones while returning to the original position.As Rosenberg describes,“Gestures materialize in an accumulating mathematical sequence (1,1+2,1+2+3,...),with each iteration contributing to the effect of choreography as visibly constructed,gesture by gesture,before the audience’s eyes,and repetition making gesture available to vision as well as memory.”[2]38Throughout theAccumulation Choreographicseries,viewers gradually become familiar with the gestures and the structure of the choreography.“When Brown ends the work,her gesture suggests the circuit of movement’s travel from its origination by the artist through the body and back to itself.”[2]39The repetition of movements and return to the beginning action reveal the originality of the movements while deemphasizing their mystery.At the same time,the choreography achieves Brown’s intention to create abstract,non-judgmental,and geometric movements based on the body’s relationship to the space.

Simple and linear as they are,the movements created by the limbs can be seen as both visible and invisible lines shaped in space.The architecture of the body,the clarity and harshness of the movements and placement of the limbs form the visible lines,while the energy extended from the tip of the fingers and toes and the traces of those movements carving the space form the invisible lines.As Kandinsky points out,“(in dance) every finger draws lines with a very precise expression.”[5]100Lying on the floor in a vertical line,the body has a center point,the pelvis,which functions as an anchor point to every part of the body,and as a reference to which the four limbs create geometric relationships.The body remains neutral,as a machine that executes the gestures,achieving a sense of graphic and structural simplicity.InPrimary Accumulation,Brown applies the “principles of abstraction and geometric simplicity”[4]403in her 1973 drawings.As Rosenberg asserts,quoting Dan Graham,such an approach to choreography makes the dance a visual art work that is “meant to be seen as non-illusionist,neutral and objectively factual,or as simply material.”[2]38

Brown’s 1973 drawings played an important role in generating movement and creating a movement quality that was abstract,geometric,and repetitive.Both methods applied to the drawing and to the choreography follow an elementary principle.The four-squares-inside-a-largersquare structure in the 1973 drawings can be categorized as Kandinsky’s “prototype of linear expression,” which consists of “a square divided into four squares.”[5]65In this formation,the intersection between the horizontal and the vertical is the center point of the square,defined as “the harmonizing of the point and the plane.”[5]65For Kandinsky,this construction is “the most primitive form of the division of a schematic plane.”[5]66Since the central horizontal and vertical lines have the potentiality for infinite movements,variations based on this formation can be a further exploration and extension of the foursquare prototype.That means Brown’s 1973 drawings can be seen as an “exploration of composition through elementary form and linear expressions.Within the form,various movements of lines can be achieved through the collaboration between tension and direction.”[5]66Likewise,the choreography Of theAccumulationseries deconstructs the complicated movement patterns by experimenting with the most basic movement initiations and spatial orientations.Through this investigation,Brown discovered an aesthetic that worked for her as an individual post-Judson choreographer and at the same time enabled her to generate and develop new materials and concepts.

In 1976,she carried on her research,applying the linear expression and composition she had explored in the 1973 drawings to a new work,Line Up.[1]The first section of the choreography starts with five dancers walking into the space,each carrying a 10-foot-long stick.They then lie down on the floor in one vertical line,holding the stick on top of their bodies while trying to connect the ends of the stick to those of the other dancers.After a long period of adjustments and reconfigurations,not only do the bodies of the five dancers form a vertical line,the sticks do so as well.In this way,lines are configured and materialized through both bodily and object forms.

In the second section ofLine Up,the dancers walk in space to form a line,leave the formation,and then create a new line.Within this process,a clear,straight line appears and disappears,resolves and dissolves.While the dancers move in and out of the lines,viewers see an invisible line formed by the physical bodies that extends into the space.

Babette Mangolte,the photographer who captured many moments of Brown’s choreography,quotes Brown’s description ofLine Up:“The line appears and is nudged into straightness; you are allowing change,being stable and flexible,talking to others,helping someone else,anticipating,warning,disconnecting,reconnecting,doing two incompatible activities at once,circling with the body,maintaining contact.”[10]45For Brown,Line Upwas “a series of negotiations” between clarity and disorder.[10]45Dancers’ efforts and struggles to create a perfect vertical line with the unyielding sticks and to swiftly make and unmake lines elsewhere amplify Brown’s choreographic interest in linear forms.

In anotherLine Upsection,Brown expands the linear gestures into idiosyncratic movements,allowing the dancers to occupy the full space with a whole range of motions.Seeing the dancing body as a geometric construct while considering its linearity,Brown experimented with bodies making lines in space.As shown in Babette Mangolte’s photograph ofLine Up,there are clear angles and horizontal,vertical,and diagonal lines within and between dancers’ bodies.When the dancers move,they embody geometric lines and shapes.In other words,dancers’ bodies are treated as lines in space.(Fig.5)

Fig.5 Babette Mangolte,Line Up,1977[10]49

Line Up(1976) echoes the linear expressions foregrounded in Brown’s 1973Accumulationchoreographic series.It transfers Brown’s 1973 drawing experiments from the paper into the dancing space; the process of dancers making and unmaking the line mirrors Brown’s exercises to draw straight and curved lines inside the square.In addition,the movement vocabulary and actions inLine Up—walking,running,lying down,and making lines—share a pedestrian,task-oriented quality inherited from the Judson tradition.Yet because of her extensive investigations of movement through drawing,Brown was able to define her credo as a choreographer in the 1970s.

Drawing as a “machine” that makes the art

Brown’s 1973 drawings represent an intellectual exploration of new movement vocabularies,allowing her to examine the energy,dynamism,and geometry of movements through the drawing process.Experiencing the virtuosity and physicality involved in the execution of the drawing,and experimenting with the essential characteristics of linear expression,Brown was able to embody the line’s kinesthetic quality in movement and incorporate the abstract geometry of lines and the dynamism of drawing into her choreography.Unlike the 1973 drawing,the 1975Locusdrawings echoes Sol LeWitt’s ideas about conceptual art,emphasizing the importance of idea and form.TheLocusscore allowed Brown to study movement and dance through the form of the cube,which provided a visual construct that not only enabled her to visually connect her dancing body to a three-dimensional space,but also propelled her as a choreographer to think about the spatial transitions between movements and spatial composition in dance.As a post-Judson choreographer,Brown continued her research in 1973 for a choreography that was abstract and logical while exploring a new vocabulary that represented an abstract aesthetic.

Contemporary with Trisha Brown in the postmodern revolution,Sol LeWitt was described by Kate M.Sellers as “a pioneer of minimal and conceptual art in the 1960s and 1970s.”[11]1Sol LeWitt shared with Trisha Brown and other artists an urgent desire to reexamine and reform the traditions in visual art.While Judson artists battled against the theatricality of modern dance and its emphasis on the artist’s individuality,LeWitt’s conceptual methodology,according to Nicholas Baume,was equally “an aesthetic affirmation generated through negation.”[11]20By negating artistic self-expression and subjectivity as well as the institutional hierarchy within American Abstract Expressionism,LeWitt freed himself from those constraints and reinvented art both conceptually and practically.

LeWitt initiated a conceptual approach to art-making not only by revisiting the creative process and studying formal structure,but also by critically examining the idea that gave birth to the work of art.As explained in his “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” the idea of a work of art is its most important aspect.The idea,for LeWitt,“becomes a machine that makes the art.”[12]LeWitt’s desire to model his artistic practices on the machine reveals his intention to minimize the artist’s subjectivity and to systematize the creative process.This concept of the machine parallels a core idea in Brown’s choreographic exploration in the 1960s and early 1970s.In a lecture-talk with performing arts curator Philip Bither and visual arts curator Peter Eleey,Brown discussed her idea of the machine in relation to the creation of dance.[13]According to Susan Rosenberg,the function of the “dance machine” is to tell you,“1) when to start,2) where you go,and 3) where you finish.”[2]33

Both LeWitt and Brown have emphasized the importance of the idea of the machine to artmaking during the period when both visual artists and choreographers were simultaneously creating new art as a rebellious act against history.According to Nicholas Baume,the transformation of dance movements from the theatrical to the pedestrian was parallel to the reorientation of art“from the visual to the conceptual.”[2]33For Brown and other Judson choreographers,there was a pressing need to find new movement vocabularies and choreographic forms that signified a complete break from existing modern dance.For LeWitt and other conceptual artists,“the rhetoric of the machine was ready-made for the aestheticideological work of negating the perceived humanism and romanticism of Abstract Expressionism.”[11]83Therefore,the emphasis on the notion of the machine was an“affirmative strategy” taken by these artists to “overcome the burden of history.”[11]20

Yet the machine’s capability of making art relies on a conditioned system and procedure programmed by the artist.In order to empower the “machine” and to actualize the related conceptual idea,both Brown and LeWitt chose drawing to bridge the gap.Brown’sUntitled (Locus)(1975) (Fig.6) drawing paved the way for the creation of theLocusdance (1975),while LeWitt’s drawing series ofIncomplete Open Cubes(1974) (Fig.7) were described by the artist himself as important “intervening steps” in the creative process of the final work.①

Fig.6 Trisha Brown,Locus,1975[14]118

Fig.7 Sol LeWitt,Incomplete Open Cubes,1974[11]51

The decision to embody and elaborate the conceptual idea in drawing revealed its potentiality for ongoing exploration.According to Jean-Luc Nancy,“drawing is the opening of form.”[15]1The form,first of all,comes from an idea.Nancy,who describes Plato’s “idea”as an “intelligible model of the real,” points out that“form is the idea” and drawing is the realization of idea through form.[15]5That is,the idea leads and propels the progression of the drawing as the form unveils and develops itself.In this process,the gesture of drawing“proceeds from the desire to show and to trace the form.Here,to trace is to find,and in order to find,to seek a form to come—a form to come that should or that can come through drawing.”[15]10In drawing,the idea gives birth to the form,which unfolds in different stages and therefore is subject to change.In this way,a drawing is both the realization of an idea and the configuration of a form.The idea constructs the form and the form in turn generates more ideas.The openness of drawing served LeWitt and Brown’s need to explore conceptual ideas through an investigation of form and transform those ideas to machines that make art.

In herUntitled (Locus)(1975) drawing,Brown used the cube as the physical form.In an interview with Hendel Teicher,Brown explained that her idea to “create a sphere of personal space” and how and where to move was both realized and visualized in the form of the cube.[7]18According to Brown’s description,the cube is marked by 27 numbers on 27 interior points.The numbers also correspond to the 26 letters of the alphabet (number 27 as the space between the words).The cube diagrams a brief biography of the artist herself.With the physical cube on paper,Brown assigned the numbers as anchor points to which she created movements.The numbers on the cube then become instructional signs that guide the direction and orientation of the movements.In this way Brown used the structure of the cube and the settings she established to create movements.As Fig.8 and Fig.9 show,after choosing the cubic form as the material realization of her idea of creating “a personal space.” Brown began to work extensively with the cube in her drawing and to follow painstakingly the instructions and restrictions she had set for herself.The task was to create movements that directionally and spatially corresponded to the number and letters in the cube as the text developed.

Fig.8 Trisha Brown,Locus Scores,1975[14]121

Fig.9 Trisha Brown,Locus Scores,1975[14]120

Similar to Brown’sLocusdrawing,Sol LeWitt’sIncomplete Open Cubes(1974) experiments with and expands upon the essential geometric construct of the cubic form.LeWitt’s procedure was to subtract multiple parts of the cube in an accumulated order while adhering to its three-dimensionality.In the drawing series,he assigned letters to the eight corners of the cube and numbers to its twelve lines.Following a subtractive method,he first took away one line to make an elevenpart piece,and eventually subtracted 9 lines out of the cube to make a “three-part variation.” As Fig.10 shows,Sol LeWitt made numerous attempts to exhaust all the possibilities through an algorithmic procedure.Though tedious and painstaking,the serial approach offered a“permutational system” that allowed him to execute his conceptual idea extensively and logically.[11]24Pamela M.Lee explains LeWitt’s seriality in an essay “Phase Piece,”where she quotes the artist’s description of his serial practice and algorithmic procedure.Serial compositions,he wrote,“are multipart pieces with regulated changes.The differences between the parts are the subject of the composition.”[11]51The idea of seriality functions as a production line,allowing LeWitt to produce “a process of ideas” that serves to discount the artist’s subjectivity in decision-making.[16]In this way,the drawing that actualizes the idea operates the serial system and performs as a machine.In other words,drawing is the machine that makes art.

Fig.10 Sol LeWitt,Incomplete Open Cubes,1974[11]8

The idea of seriality in Brown’sUntitled(Locus) is implicit and yet crucial.In the drawing,Brown breaks down the movements number by number,exploring the connection between each changed movement and the spatial dimension related to that change.Brown’sLocusdrawing score is also a kind of “serial composition.”The directions of the movements of the limbs are subject to change sequentially and spatially according to the locations of the 27 numbers in the cube.The changes where the body should go and how a movement is connected to what precedes and what follows it are regulated by the two-dimensional square inside the cube and its spatial relationship to the three-dimensional cube,and by the human figure’s relationship to the cubic space.

In her 1973 drawings and in theAccumulationchoreographic series,Brown investigated the originality of movements through a series of accumulated actions in which the dancing body is constantly referred to.Two years later,Brown’sLocusdrawing was again used to explore the spatial orientation of the dancing body and movements.Now the human figure was placed inside a cubic space while Brown’s instructions tracked how the body moved in that space.A study of the elemental progression of movement inside a three-dimensional space,theLocusdrawings therefore implied “the orderly,systematic elaboration of the idea,”[11]27while enabling Brown to make and assess dance movements that were abstract and logical.

On one hand,the idea of seriality allowed both Sol LeWitt and Trisha Brown to immerse themselves in the“procedures,progressions and systems that establish autonomous rules of artistic operation.”[11]20On the other hand,it is the formal structure of the cube that performed the seriality.In the early 1960s,Sol LeWitt had already begun experimenting with “grid-based modular progressions of the basic element,the cube.”[11]23As Baume notes,“LeWitt was attracted to the cube as a‘grammatical device,from which the work may proceed,’finding it ‘relatively uninteresting’ in itself.”[11]22For LeWitt,the cube was a “simple and readily available form (that) becomes the grammar of the total work.” It is a basic geometric form,whose neutrality,abstraction,and simplicity provide freedom and open structure,while being sufficiently familiar to allow modifications of the basic shape.

Like LeWitt,Trisha Brown chose the cube as the foundational structure in herLocusdrawing.At the same time,she was well aware of the form’s threedimensionality,the second essential characteristic of the cube’s geometric construct.By assigning 27 numbers to the 27 points on the cube,Brown was able not only to mark the constituent parts of the cube,but also to dissect its geometry and composition to identify the basic three-dimensionality of the structure.This approach was implemented as a result of the artists’ awareness of the spatial volume of the cube and the recognition of its openness.

The third quality of the cube that plays a major role in both the drawing and dancing ofLocusis its combination of uniformity and adaptability.An isometric geometric shape whose constituent parts are equivalent,the cube has an infinite potential for movement.As seen in Fig.11,in LeWitt’s earlierModular Cube(1965),there are multiple identical cubes inside the larger cube.These small cubes are adjacent to each other,sharing common squares and lines while collectively dividing the volumetric space of the original cube.Likewise,in Brown’sLocuscube (Fig.6),the dashed lines connecting all the numbers in the cube divide the cube into 8 smaller matching cubes,an approach similar to LeWitt’sModular Cube.In this way,Brown was able to detect the geometric construct inside the cube,its dimensionality,grid base,visible and invisible lines,squares,and cubes.The uniformity of cubes implies both containment and infinite expansion in all directions.The multiplicity of symmetrical lines,squares,and cubes can be seen as a captured movement trajectory of one single elemental cube,which moves horizontally,vertically and diagonally.Mona Sulzman was one of the four original dancers inLocuswhen it premiered in 1975.In her articleChoice/Form in Trisha Brown's “Locus”:A View from Inside the Cube,Sulzman draws attention to how Brown succeeded in discerning the cube’s potentiality for generating movements in the drawing process,and then applied the discovery to the creation of theLocusdance.

Fig.11 Sol LeWitt,Modular Cube,1965[11]6

According to Brown’s description of the creative process quoted in Sulzman’s article,she first made “four sections each three minutes long that move through,touch,look at,jump over,or do something about each point in the series,either one point at a time or clustered.”[14]118Since the points were correlated to Brown’s text,“there is spatial repetition,but not gestural (repetition).”[14]118In other words,points in the cube would be revisited by the dancing body with different gestures and movements throughout all four sections,creating familiarity and a recurrence of spatial orientations.Recognizing the cube’s adaptability,Brown then expanded and multiplied the units of its base,forming “a grid of five units wide and four deep.”[14]118The dancing space thus consisted of multiple connected equivalent cubes,a spatial construct that provided “opportunities to move from one cube to another without distorting the movement.”[14]118Dancers inside the cube were not only able to perform the movements by following the spatial instructions inside one cube,but also to change their facing and directions and travel to other cubes to continue the choreography.

Because of its simplicity and potential for movement,the cube thus becomes what LeWitt called,“an intrinsic part of the entire work.” It is this cubic form that initiates and advances the choreographic composition.In the drawing,the original cube is a spatial constraint that regulates Brown’s movement; in the actual dance,where the four dancers perform the four sections in various orders,the form expands the dimension,suggesting multiple facings and liberating the dancers to create new spatial orientations.Sulzman writes that when she performedLocus,she had “access to and participated in the total structure of the piece.”[14]124The geometric construct of the cube and the “rigorous structure ofLocus” found their way into the choreography not only as a spatial reference,but also as a formal structure that develops the whole composition of the piece.

Thanks to a clear understanding of the geometric characteristics and construction of the cube,Brown was able to connect her drawing and dancing conceptually,and realized a shared idea in both art forms.The cube’s three-dimensionality enabled Brown not only to insert a complete human body inside the cube,but also to make the dancing body take advantage of the surrounding spatial volume.The stability of the cube and the uniformity of its construction eased the complicated process of tracking and signaling the directions of the movements with numbers.The simplicity and adaptability of the cubic form offered both freedom and infinite possibilities,even as Brown strictly followed the rules in the drawing and only created movements that corresponded to the points and numbers.

According to Susan Rosenberg,“The Gestalt of the cube,its words and sentences and drawn score,elevated the significance of its geometric structure and systematic task instructions.”[2]40The cubic form performs the seriality,which maps out a structured procedure that realizes an autonomous creative process.In addition,Brown’sLocusscoresare the “machines” that function as “objective mechanisms that collaborate with the choreographer” to develop the dance.[17]However,the drawing does not figuratively or meticulously design the movements.On the contrary,it abstractly orientates the direction of the movements,making them visually clear and logical.A “visual construction,” theLocusscore and the drawing process itself leave space and freedom for the creation of the dance.[2]40In this way,drawing does not replace choreography in the creative process.Or rather,it complements dancing with its visual and structural qualities.

Brown’s effort to “pin down” poly-directional movements initiated the idea of “creating a sphere of personal space.” The idea functioned like a machine,as Susan Rosenberg explains,“for moving through space and generating a vocabulary of gesture” that is abstract and logical.[2]40Such a concept was then realized through a physical reality of form in Brown’sLocusdrawing.What’s most important is the geometric formation of the cube,its simplicity and clarity for imagination and visualization so that when the form in the drawing is transferred to dance,“the form of the single cube gives rise to the full structure of the piece.”[14]124For Trisha Brown and Sol LeWitt,the cubic form residing in their drawings therefore functioned as a visual strategy that embodied their shared conceptual ideology and challenged the burden of history.

In theLocusscore,the cubic structure “visualizes choreography as architectural construction.”[2]42Developed from theLocusdrawing,theLocusdance emphasized the visual,the geometric,and the formal aspect of choreography.According to the Trisha Brown Dance Company’s associate artistic director Diane Madden,theLocusscore,like Brown’s 1973 drawings,functions as a “choreographic map.” It introduces the dancers to a visual structure that creates a sphere of space around them.The score indicates not only “a clear sense of movement direction” but also a “spatial design” that fabricates spatial relationships between dancers,and between dancers and their space.Madden recalls that in the process of developing theLocusdance,“Brown tried different ways of progressing through increasing degrees of improvisation.”②The process started with Brown going through the same sequence of points in the cubic structure four times,creating fourLocussolos.As the idea of dancing within an imaginary cube operated throughout the whole choreography,its geometric structure and dimensionality allowed dancers to shift their orientation and keep the direction of movements unchanged at the same time.Dancers then had the independence to make choices and decide where to travel,what cube to be in,and whom to dance with.

Mona Sulzman reflects upon her experiences dancing in theLocusquartet both as an individual within her imaginary cube,and as one of the four dancers with whom she shared physical and spatial contact.“It is this simultaneity that brings (the dancers) pleasure;our concentration extends outside the cube and allows us to share the magic of the very structure that has brought about this particular formal and kinesthetic relationship.”[14]129In other words,the drawing score,along with its cubic structure,yields both “uniformity”and “transformation.”[14]130On one hand,the drawing framed the dancers’ movement orientation.On the other hand,it broke the rigid structure,allowing the dancers to improvise and explore,letting chance and its excitement happen.Instead of limiting the vision,Locusallowed Brown and the dancers to see the space inside and beyond the cube.

In her 1973 drawings,Brown traced the connection between the lines on paper and the bodies as lines in space; therefore,in the creative process of theAccumulationchoreographic series,Brown implemented an investigation of movement vocabularies and generated new movements that embodied a linear,geometric quality.In her invention ofLocus,Brown adopted the cubic form not only as a visual strategy to study form and choreographic composition in dance,but also as a method to develop a system of logic for dancers.

Conclusion:The body is intelligent,and the mind is physical

Brown’s drawings of the 1970s,along with her choreographies of the period,established a conceptual,structural,and movement foundation.These early non-proscenium works revealed what Diane Madden called,“the bones of choreography,” which is a “basic relationship between structure and dancer.”[18]

The foundation set up in the 1970s remained firmly in place in all Brown’s later works,in which there was a consistent recycling of movement vocabularies as well as a continuous awareness of spatial compositions and choreographic structures.As a practice and means of investigation,drawing was an artistic tool that offered Brown “a sense of direction building on where she was coming from,” allowing “research and discovery,improvisations and chances” to be part of the choreographic process.③Though Brown’s drawings retained their own trajectory and progression,they had always kept a proximity to the dancing through a shared bodily and kinesthetic attention.

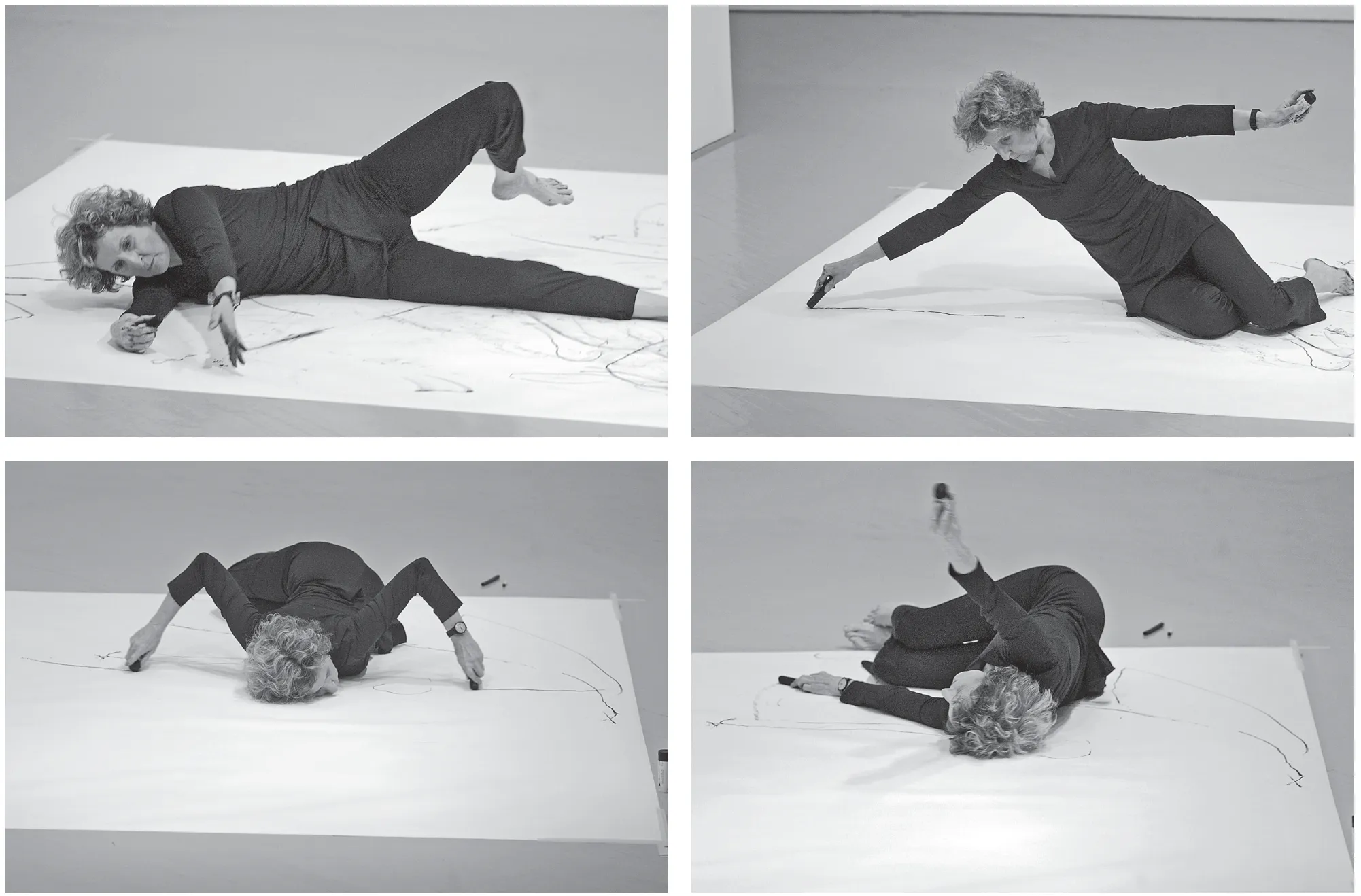

While Brown’s 1973 drawings only imagined the movements of the limbs on paper,the 1975Locus scorepaid attention to the whole dancing body by visualizing its surrounding space through the cube.As Cornelia H.Butler points out,these early notebook drawings indicated “a conjunction of body and space” represented by simple lines and a cubic form.[19]193Later on in 2003,this “exploration of the conjunction of body and page grew in scale,” and the bodily awareness in the drawings were fully developed and intensified in Brown’s work,It's a Draw(2003) at the Fabric Workshop and Museum.The video of this performance drawing shows that Brown sets herself on a large piece of paper on the floor and uses her whole body to draw,“treating the frame of the paper as a stage.”[3]25Moving across the paper with charcoal and oil pastel in her hands and toes,Brown pivots,lies down,rolls over,extends her arms and legs and jumps,executing a series of movements and leaving their dynamic traces on the drawing paper,as seen in Fig.12.Not limiting herself to the paper frame,Brown often steps out of the sheet,looking at the drawing and contemplating for a while,and returns to the frame to continue her actions.[20]

Fig.12 Trisha Brown,performing,It's a Draw/Live Feed,2003,Philadelphia Museum of Art[20]

It's a Drawpresented to the audience both the durational creative process and the permanent final product.In this way,the drawing became an extension of Brown’s body and her dance.Here,the corporeal body mediated the drawing and the dancing,kinesthetically leaving traces and cutting through the drawing surface and the physical space,while intentionally “yielding a visual object that is genetically part drawing,part performance.”[19]193

InIt's a Draw(2003),Brown continued the exploration of acceptable gestures in dance through her drawings,a movement research she initiated in the 1970s.IfIt's a Drawis seen as a drawing work,then the dancing body is the primary medium of execution;if it is considered as a choreography or a performance,then the drawing displays a heightened bodily awareness and recalls the tension,direction,and kinesthesia in movements.In both cases,Brown’s body acquires a cognitive perception through the rendering of form and the execution of movement.

The relationship between Brown’s dancing and drawing is both independent and interdependent.Her integration of dancing and drawing in her creative process indicates,as Catherine Lord argues,an understanding that the body thinks and “sets in motion its own theorization of motion.”[8]21Lord emphasizes that the body is intellectual and the mind is physical:dance requires intelligent thinking while in drawing,the mind follows physical,corporeal impulses and desires to trace the lines of the body and its dimensions.The mind shares a kinesthetic intention while the body follows a sense of logic to move.From the 1970s drawings to the performance drawing in 2003,Brown continued to blur the distinction between drawing and dancing,embracing drawing’s “conceptual discursiveness,formal possibilities,and its economy of means.”[19]139By applying both dancing and drawing to her choreographic process,Trisha Brown was able to connect her mind and her body,and to actualize abstraction and rationality in her choreography.Recognizing drawing not as an act of painting but as an art form that allowed intellectual exploration and accepting the pedestrian quality of movements while revealing their linearity,Brown not only challenged the institutional hierarchy of art before the 1960s,but also discovered her own experimental creative processes and choreographic approaches.Brown’s investigation in dancing and drawing cultivated a deeper understanding and appreciation of her intellectual inquiry as an artist,and at the same time,contributed to the ongoing interdisciplinary conversation between choreography and visual art in the 20th and the 21st century.

[Notes]

① In “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art” LeWitt states that “If the artist carries through his idea and makes it into visible form,then all the steps in the process are of importance.The idea itself,even if not made visual,is as much a work of art as any finished product.All intervening steps—scribbles,sketches,drawings,failed works,models,studies,thoughts,conversations—are of interest.Those that show the thought process of the artist are sometimes more interesting than the final product.”

② These lines are from an interview with Diane Madden by the author,Lu Shirley Dai,on 9 December 2015.

③ See in ②.