The evidence for the impact of policy on physical activity outcomes within the school setting:A systematic review

2021-05-22CtherineWoodsKevinVolLimKellyBlthCseyPeterGeliusSvenMessingSrhForergerJeroenLkerveldJonnZukowskEnriqueGrBengoeheonehlthePENonsortium

Ctherine B.Woods,Kevin Vol,Lim Kelly,Bl′th′ın Csey,Peter Gelius,Sven Messing,Srh Forerger,Jeroen Lkerveld,Jonn Zukowsk,Enrique Gr′ı Bengoehe,on ehl o the PEN onsortium

a Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences,Health Research Institute,University of Limerick,Limerick V94 T9PX,Ireland

b Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg,Erlangen 91058,Germany

c Leibniz Institute for Prevention Research and Epidemiology-BIPS,Bremen 28359,Germany

d Department of Epidemiology and Data Science,Amsterdam Public Health Research institute,Amsterdam UMC,VU University Amsterdam,Amsterdam 1081 HV,the Netherlands

e Upstream Team,Amsterdam UMC,VU University Amsterdam,Amsterdam 1081 HV,the Netherlands

f Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering,Gda′nsk University of Technology,Gda′nsk 80-213,Poland

Abstract Background:Despite the well-established health benefits of physical activity(PA)for young people(aged 4-19 years),most do not meet PA guidelines.Policies that support PA in schools may be promising,but their impact on PA behavior is poorly understood.The aim of this systematic review was to ascertain the level and type of evidence reported in the international scientific literature for policies within the school setting that contribute directly or indirectly to increasing PA. Methods:This systematic review is compliant with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis guidelines.Six databases were searched using key concepts of policy,school,evaluation,and PA.Following title and abstract screening of 2323 studies,25 progressed to data synthesis.Methodological quality was assessed using standardized tools,and the strength of the evidence of policy impact was described based on pre-determined codes:positive,negative,inconclusive,or untested statistically. Results:Evidence emerged for 9 policy areas that had a direct or indirect effect on PA within the school setting.These were whole school PA policy,physical education,sport/extracurricular PA,classroom-based PA,active breaks/recess,physical environment,shared use agreements,active school transport,and surveillance.The bulk of the evidence was significantly positive(54%),27%was inconclusive,9%was significantly negative,and 11%was untested(due to rounding,some numbers add to 99%or 101%).Frequency of evidence was highest in the primary setting(41%),34%in the secondary setting,and 24%in primary/secondary combined school settings.By policy area,frequency of evidence was highest for sport/extracurricular PA(35%),17% for physical education,and 12% for whole school PA policy,with evidence for shared use agreements between schools and local communities rarely reported(2%).Comparing relative strength of evidence,the evidence for shared use agreements,though sparse,was 100%positive,while 60%of the evidence for whole school PA policy,59%of the evidence for sport/extracurricular PA,57%of the evidence for physical education,50%of the evidence for PA in classroom,and 50%of the evidence for active breaks/recess were positive. Conclusion:The current evidence base supports the effectiveness of PA policy actions within the school setting but cautions against a“one-sizefits-all”approach and emphasizes the need to examine policy implementation to maximize translation into practice.Greater clarity regarding terminology,measurement,and methods for evaluation of policy interventions is needed.

Keywords:Evaluation;Physical activity;Policy;School;Systematic review

1.Introduction

Physical inactivity is the 4th leading risk factor for premature mortality worldwide.1To improve public health and to prevent non-communicable diseases,the World Health Organization(WHO)physical activity(PA)guidelines recommend at least 150 min of moderate-to-vigorous PA(MVPA)per week for adults and at least 60 min of daily MVPA for children.2Despite all the evidence of benefits,epidemiological data indicate that 28% of adults and 81% of children and adolescents globally do not meet PA recommendations.3,4Research consistently shows that PA levels decline during adolescence,5-8that boys are more physically active than girls9,10and that PA habits developed in childhood track into adulthood.11-15Therefore,methods to effectively address such high levels of inactivity in children are urgently needed.

A substantial body of literature exists on solutions that can address the inactivity challenge.Guided by an ecological approach,this literature points to a multi-level response that addresses personal,environmental,and policy factors.16Approaches that address all these levels have been used previously to successfully reduce the use of tobacco products.17There has been an exponential growth in policies targeting the upstream determinants of health behaviors to reduce the burden of lifestyle-related diseases like physical inactivity.18Examples include WHO’s global action plan for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases,19which included a global target of reducing population prevalence of inactivity by 10% by 2020.More recently,WHO’s global action plan on PA recommended a systems-based approach and identified 20 policy actions for enhancing population levels of PA,including whole-of-school approaches.20Thus,understanding the systemic drivers of inactivity is paramount because in doing so we can hope to help promote PA not only to improve health but also to address the global syndemic,or the combined pandemics of obesity,undernutrition and climate change and their threats to human health and survival.21

Schools are an important setting because they reach the majority of children and adolescents,who spend a substantial amount of time in this setting.Whole-of-school approaches for the promotion of PA are recommended,20,22yet there is a lack of studies focusing explicitly on the evidence for PA policies within this setting.Under whole-of-school approaches,the policy level is an important component.An article by Lounsbery23explains how the presence or absence of policies related to PA,their nature(mandatoryvs.recommended)and their level of implementation success can have substantial and direct implications for children’s PA.They also articulate the different levels and key policy makers within each level,for example at national level—the minister or governor,at regional level—the school board,and at school level—the principal,and at classroom level—the teacher.However,PA policy implementation is not straightforward.PA policies vary widely and generally lack specificity,implementation,accountability,and funding.24There is a need to investigate the status of the evidence for policies that increase PA within the school setting.

For the purpose of this paper,policies are defined as“decisions,plans,and actions that are enforced by national or regional governments or their agencies(including at the local level)which may directly or indirectly achieve specific health goals within a society”.18The role of policy is to change systems instead of individuals,and in doing so,create supportive contexts in which programs and environments collectively can reduce non-communicable diseases,including obesity.Importantly,policy interventions are not to be confused with other types of program or environmental interventions;policy interventions provide the framework in which the programs or environmental changes are tendered,developed,financed,or implemented.25

Several frameworks exist that advocate for the use of policy as an instrument to promote health within the school setting.These frameworks mainly focus on a broad definition of health;however,they provide a useful conceptual starting point for reviewing the potential direct and indirect effects of policy on PA.The WHO published the diet and physical activity strategy school policy framework to guide policymakers at national and sub-national levels in the development and implementation of school policies.26This framework highlighted that children are not immune to the negative consequences of physical inactivity,and it called for urgent action to effect change.This action included the development and implementation of policies that promote PA.More recently,the Creating Active Schools Framework was designed using a“systems”approach to identify all components of a whole school PA approach.27This framework presents the school as a complex adaptive system,one that places an“active school”as central to the school’s beliefs,customs,and practices that drive school policy.Through engaging with key stakeholders—children,teachers,management,parents,and the wider community,an“active school”creates the necessary physical and social environments within which schools can facilitate different types of PA opportunities.

Although these frameworks provide a useful theoretical background on PA policy within the school,the evidence presented in them is mainly descriptive;it explores policy content,presence,and level of implementation.No evidence on the effectiveness of policy,nor any reference to the policy evidence-base,is evident within these framework documents.This represents a gap in our knowledge.Thus,the rationale for this systematic review is aligned to the work of the Policy Evaluation Network(PEN;https://www.jpi-pen.eu/),which aims to develop a consolidated approach to policy evaluation across Europe by developing and prioritizing an agreed-upon set of indicators,measured using harmonized instruments that ideally can be used by existing monitoring and surveillance systems.18Although research in PA is still mainly focused on its health effects(Type 1)or on the effectiveness of specific PA interventions(Type 2),there has been limited growth in research on policy and PA(Type 3).28,29Although we are developing a better knowledge of PA policy,there are gaps in our understanding and evidence for the effectiveness of PA policies.30Therefore,the purpose of this paper was to evaluate the status of the evidence base for the impact of policy on PA outcomes within the school setting.

2.Methods

The review is structured according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis(PRISMA).31It has been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews(PROSPERO,CRD42020156630)and the study protocol has been published.32

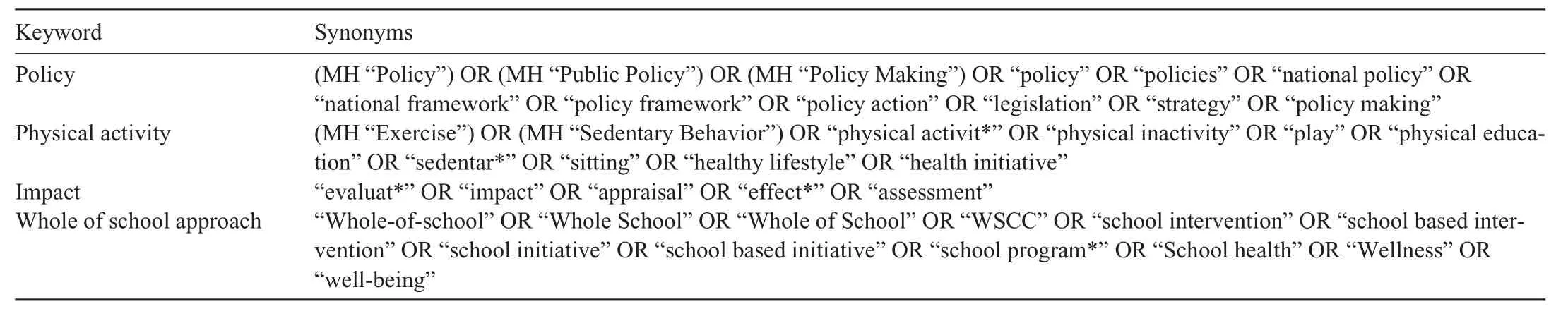

Table 1Search terms.

2.1.Search strategy

A systematic search of the following electronic databases(limited to titles and abstracts)was conducted during November 2019 through January 2020:MEDLINE(EBSCO),Sport-Discus,CINAHL,Cochrane,Web of Science,and Scopus.Search terms are presented in Table 1.Search results were limited to articles that were identified through a systematic stepwise identification approach,starting with screening of titles and abstracts.Duplicate studies and studies not in the English language were removed.This search was supplemented by manual reference checks of original reviews that were found in the systematic search.

2.2.Eligibility criteria

Studies were included based on criteria for(a)study type,(b)participants/population,(c)policy exposure,and(d)outcomes.

(a)The following study types were eligible for inclusion:(1)reviews and(2)empirical studies.Reviews(used to inform the Introduction and Discussion sections of this paper)could include systematic,scoping,and realist methods,all of which must have used a comprehensive search strategy.In addition,reviews must have reported an analysis of original research.Empirical studies could include randomized control studies,non-randomized studies,cohort studies,qualitative studies,and mixed-method designs.

(b)Included review studies must have targeted children and/or adolescents,albeit not exclusively within the school setting or with this population.For empirical studies,the study must have targeted children,adolescents,and teachers in the school setting only.

(c)The authors are not aware of any reviews to date that have exclusively assessed the impact of PA policy in the school setting.Therefore,included reviews did not need to meet this aim,but they did need to address some policy-related component that promoted PA within the school setting.Empirical studies must have referenced the impact of policy in the school setting.“Direct”policy refers to policies where the primary aim is improving the PA environment and increasing PA participation.“Indirect”policy refers to policies where the primary aim is not to increase PA levels,but this may occur as a co-benefit of successful implementation(e.g.,car-free school streets).

(d)All study designs(reviews,empirical evidence)had to include the one or both of the following outcome(s):(1)a change in PA(or proxy,i.e.,fitness),assessed by means of self-report,wearable devices(e.g.,accelerometer)or observational measure(e.g.,System for Observing Fitness Instruction Time33)and(2)a change in features of the physical and social environment(e.g.,facilities,equipment,action plans,programs)hypothesized to lead to changes in PA outcomes as a result of a policy intervention.Empirical studies were excluded if a direct or indirect form of policy intervention was not identifiable or if there was no information provided regarding the effects of the policy under consideration on the desired outcomes.

Our systematic review was supplemented by a targeted search of the grey literature,although this was not exhaustive.Book chapters and policy documents issued by major national and international stakeholder organizations(e.g.,WHO)referred to in the reference lists of included papers were consulted in order to inform the Introduction and Discussion sections of the paper.

2.3.Screening of studies

Two of the authors(KV and LK)screened all retrieved titles and abstracts using the systematic review software Rayyan.34After initial title and abstract screening,full texts were retrieved and crosschecked against the inclusion criteria by two of the authors(KV and LK).When necessary,eligible studies were also crosschecked by a third author(EGB).Discussion was held where the authors disagreed on inclusion of studies until agreement was reached.

2.4.Data extraction

Data were extracted using pre-defined criteria from all study designs(reviews,empirical studies,and grey literature/other).Data included type of study design,country of origin,demographics related to the school setting and policy description and content.To allow for the interpretation of the impact of the policy identified,information on changes in the outcomes of interest(PA and/or physical/social environment)was also collected.All data extraction was conducted by 2 authors(KV and LK)and checked and expanded by a third reviewer(EGB).

2.5.Quality assessment process

Risk of bias was assessed by 1 reviewer(EGB)and checked by another(BC).Discrepancies were resolved by consensus,where necessary,in consultation with a third researcher(CBW).Similar to the methods used by Messing et al.,35we calculated the percentages of criteria met per study based on the criteria applicable to the type of study design.Studies were not ranked by methodological quality.The quality of the included quantitative studies was assessed by means of an adapted Downs and Black checklist tool.36The Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews scale was used for the assessment of systematic reviews and comprehensive reviews,including reviews of reviews.37The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme qualitative checklist was used to assess the quality of included qualitative studies.38All tools were slightly modified to meet the aims and context of our review.

2.6.Data analysis

A narrative synthesis of the included empirical studies was used to interpret and analyze the data.Extracted PA outcome data were tabulated to determine the impact of policy on PA behavior and/or environment.This data were also used to outline how policy areas were defined,delineated,and identified(e.g.,if a single study dealt with multiple policy areas).Evidence on the effectiveness of policy was described using the method described in Panter et al.,39where the observed effects of policy actions were coded as“significantly-positive”(+),“significantly-negative”(-),“no significance test”(?),or“inconclusive”(0).The number of codes per policy area is presented to show differences in frequency with which each area was studied.To allow for relative comparison,the strength of evidence is presented as a percentage of positive,negative,untested,or inconclusive codes found within each policy area or policy action,where relevant.For the purpose of clarity,Table 2 describes the terms used in the presentation of the results,and Fig.1 shows the relationship between concepts.

After data extraction on review papers and multi-component empirical studies that met the inclusion criteria was completed,17 papers(8 reviews and 9 multi-component empirical studies)were not included in data synthesis.The rationale for this was the lack of clarity in attributing evidence of impact on PA to policy.Details on these 8 reviews are listed in Supplementary Table 1,40-47with a further 9 multi-component studies detailed in Supplementary Table 2.48-56Reference lists from these papers were used to identify additional studies that may have been missed in the initial database search.Furthermore,recurring headings in narrative reviews and book chapters were used to develop the policy areas used in the data synthesis and to frame the Discussion section of this manuscript.

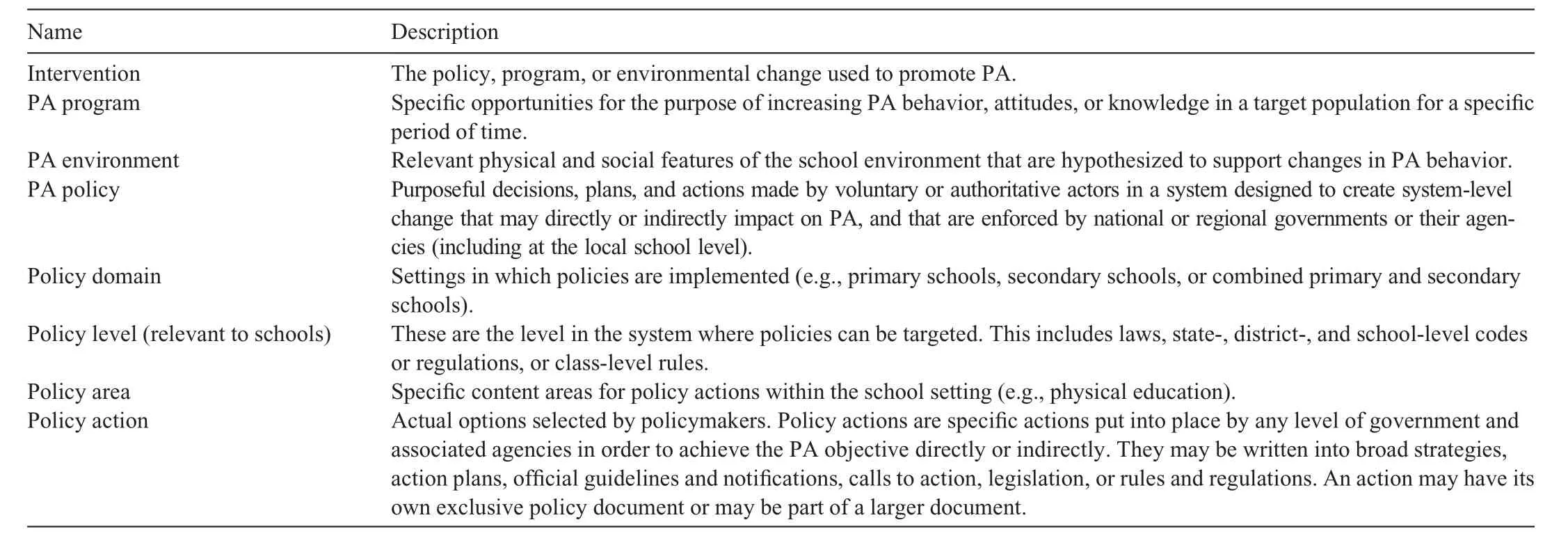

Table 2Inter-relations among policy-related concepts used in this review.

3.Results

3.1.Characteristics of included studies

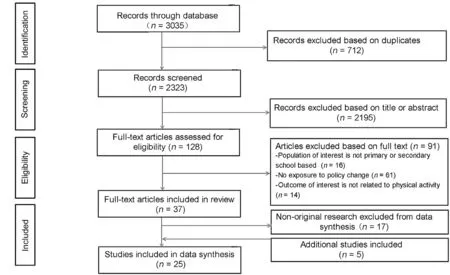

In total,3035 publications were identified,of which 712 were removed as duplicates.The remaining 2323 titles and abstracts were screened;with 2195 removed,leaving 128 full texts for review.The main reasons for exclusion based on title or abstract were that the studies were not PA related(60%,n=1317)or the studies did not describe a policy intervention(12%,n=264).An additional 91 studies were excluded based on a full-text reading.A total of 5 more papers were included following reference checks,leaving a total of 25 papers included for data synthesis(Fig.2).The most common reasons for excluding studies after full screening were that there was no evidence of a policy or that the policy impact on PA was not clear.Papers based on research in a childcare setting were excluded on population grounds,in accordance with our definition of what constitutes a school.Additional details on these papers,as well their quality ratings,are described in Supplementary Table 3.

Fig.1.Diagram of inter-relations among policy-related concepts used in this review.PE=physical education.

3.2.Study design and location

Of the 25 studies included,44% were pre-post studies,24% were quasi-experimental,24% were cross-sectional,4%were qualitative,and 4%were randomized experiments.Most studies were conducted in the USA(60%),followed by Canada(16%),the UK(8%),Australia(8%),Slovenia(4%),and Belgium(4%).Quality ratings ranged from 42%to 92%,with most studies obtaining a rating of 60% or more,suggesting at least moderate methodological quality according to current standards and conventions.

3.2.1.Population

Included studies were based in either primary(n=12),secondary(n=8),or combined primary and secondary(n=5)school settings and represented a sample of more than 370,000 students(an approximation from 24 studies reporting sample size),with a range of 120 to 220,000 students across studies.The reported age of included students ranged from 4.0 to 19.0 years.The number of schools sampled in each study ranged from 4 to 450,with a combined total of 1984 schools across all included studies(25 studies reporting the number of schools).

Fig.2.Study inclusion flowchart.

3.2.2.Exposure

Studies typically reported on state,district,or local public policies(e.g.,related to the implementation of physical education(PE)standards).Others reported on organizational policies(e.g.,shared use agreements(SUAs)between schools and local communities)or on school-level regulations relating to PA provision during curricular time.In the area of extracurricular provision,school sport policy was paramount.Two models for the provision of school sports were frequently mentioned or compared:interscholastic/intervarsity(IS)and intramural(IM).57-61IS sports refer to sports played between schools and are generally more competitive.60For this reason,places on the team are typically limited.By contrast,IM sports refer to sports played within the school institution,and participation is typically inclusive of all skill levels.

3.2.3.Outcome measures

The included studies used a range of PA outcome measures,including device-measured(n=10),self-report methods(n=11),observational methods(n=6),and qualitative methods(n=3).Device-measured methods included accelerometers(n=6),pedometers(n=2),fitness test batteries(n=1)and,other,including Geographical Information Systems,the Measuring Wheel method and the Healthy Afterschool Program Index-PA(n=1).In studies using accelerometers,MVPA,moderate PA,and vigorous PA(VPA)were the most commonly reported outcomes.Observational methods were used in 6 studies,with 2 outcome measures being used across these studies.These were the System for Observing Play and Leisure in Youth(n=4)and the System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities(n=2).A range of self-report methods was used(n=20 surveys/questionnaires),including the school PA policy assessment instrument(S-PAPA).Qualitative methods consisted of structured or semi-structured interviews(n=3).Details on the outcome measures for each study are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

3.3.Policy areas and policy actions

3.3.1.Summary findings

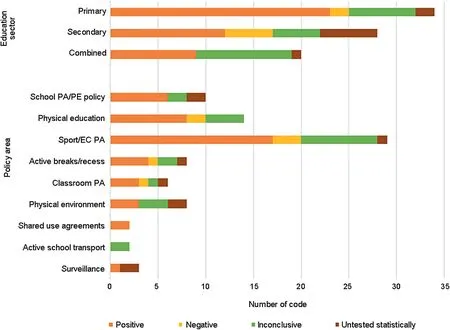

The primary search identified a total of 9 policy areas,with 22 specific policy actions for which there were 82 evidence codes(Table 3).The bulk of the evidence,54%(n=44 codes)was“significantly positive”.A total of 27%(n=22 codes)of evidence was“inconclusive”,9%(n=7 codes)of evidence was“significantly negative”,and 11%(n=9 codes)indicated that there was“no significance test”.When analyzed by education sector,frequency of evidence,41%(n=34 codes)was highest in primary school settings.A total of 34%(n=28 codes)of the evidence occurred in secondary school settings,and 24%(n=20 codes)occurred in combined school settings(due to rounding,some numbers add to 99%or 101%).Fig.3 and Supplementary Table 4 show that primary schools had the highest percentage,68%(n=23 codes),of positive policy actions;and,although infrequent,negative evidence(18%,n=5 codes)was highest in secondary schools.Inconclusive evidence was highest in combined schools(50%,n=10 codes).Fig.3 also shows that when analyzed by policy area,frequency of evidence was highest for school sport/extracurricular PA(35%,n=29 codes),followed by physical education(17%,n=14 codes),and whole school PA policy(12%,n=10 codes).The evidence for policy impact on SUAs(2%,n=2 codes)and active school transport(AST;2%,n=2 codes)was rarely reported.Comparing relative strength of evidence across policy areas,the evidence for SUAs,though sparse(n=2 codes),was 100% positive.For other policy areas,evidence of policy impact was mixed.A total of 60%(n=6 codes)of the evidence for whole school PA policy was positive.The percentage of positive evidence for sport/extracurricular PA was 59%(n=17 codes),for physical education it was 57%(n=8 codes),for classroom PA it was 50%(n=3 codes),for active breaks/recess it was 50%(n=4 codes),for physical environment it was 38%(n=3 codes),and for surveillance it was 33%(n=1 code).The evidence for AST was inconclusive.A more detailed analysis is given in each section below.

3.3.2.Whole school PA policy

In the area of whole school PA policy,1 policy action was identified;10 publications24,62-70addressed overall or multi-component policies for PA established by individual schools.This represented 12%(n=10 codes)of the total evidence and comprised positive(60%,n=6 codes),63-66,68,69inconclusive(20%,n=2 codes)24,70and untested(20%,n=2 codes).62,67This action was more prevalent in primary schools than in secondary schools.In primary schools,71%(n=5)63-65,68,69of codes were significantly positive,while 1 code was both inconclusive24and untested.67For secondary schools,there was a single untested code,70while studies on combined primary and secondary schools had 2 codes(one significantly positive66and one inconclusive62).

3.3.3.PE

Six policy actions were identified in 6 studies24,61,62,71-73for the“Physical Education”policy area,which represented 17%(n=14 codes)of the total evidence.The policy action“Require a minimum time in PE”was found to be effective in promoting PE and PA.24,61,72,73Lounsbery and colleagues24found that“Require a minimum time in PE”was positive at the district level but not at that school level;Kahan and McKenzie61found this policy action to be positively related to IS but inconclusive for PA clubs.Both discrepancies were related to implementation.The policy actions“Require PE teacher training”,24,61“Require adherence to PE standards”,24and“Evaluate PE outcomes regularly”24were associated with mainly favorable PA outcomes.Negative evidence was found for“Require adherence to PE curriculum”,and inconclusive evidence was found for“Measures to reduce PE class size”24at the primary school level.More positive evidence for this policy area was found in primary(67%,n=6 codes)than in secondary(50%,n=2 codes)schools.Therefore,evidence suggests that studies on policy actions in PE are more prevalent and are more likely to be effective in primary schools than in secondary schools.

Table 3Frequency of publications investigating each policy action.

Fig.3.Evidence code frequency and strength by education sector and by policy area.EC=extracurricular;PA=physical activity.

3.3.4.Sport/extracurricular PA

Six policy actions were identified in 11 studies57-62,66-69,71for the policy area“Sport/extracurricular PA”from 11 publications,57-62,66-69,71which represented 35%(n=29 codes)of the total evidence(Table 3).The effects of 2 sport delivery policies,IM and IS,were described in detail in the reviewed studies.Evidence was more prevalent and more positive for IM(73%,n=8 codes)57-62in comparison to IS(50%,n=3 codes),58-60with participation being greater under the IM model(35.9%vs.27.3%,respectively).58Few studies reported on policy in this area within primary schools(5 codes),with 3 studies showing positive effects for policies supporting afterschool PA programs,65,68,691 code for supporting teacher training in this area65and a single negative code for IM sport.67Research in secondary schools(n=15 codes)was more prevalent,with positive effects most frequently being reported for IM sport policies.57-59,61Some positive support was found for the IS model,with 2 positive codes,57,58but a single code each for inconclusive,58negative,57or untested61was also found for this model.Gender differences were found in relation to sport participation policy,with girls being more likely to participate when a broad range of sports were offered,thus encouraging choice,but girls were less likely to participate if the number of individuals allowed to access sport was unrestricted.60

3.3.5.Active breaks/recess

Two policy actions were identified in 7 studies62,64-66,70,71,74for the policy area“Active breaks/recess”,representing 10%(n=8 codes)of the total evidence.The policy action“Require minimum PA time in breaks”was coded as significantly positive in primary schools64and as both significantly positive62and inconclusive66in primary and secondary combined schools.The policy action“Provide structured and free play PA/sport during break”was coded as significantly positive64,65or inconclusive74in primary schools and as significantly negative71or no test70in secondary school settings.Evidence64suggests that policies promoting free play during break can be effective in increasing PA in primary schools.An example can be provided from the Australian context,in which a“no hat,no play policy”was replaced with a“no hat,play in the shade”policy.64

3.3.6.PA in the classroom

A single policy action was identified in 6 studies62,70,71,74-76for the policy area“PA in the classroom”,representing 7%(n=6 codes)of the total evidence.Broadly positive results were found for primary schools,with 66%(n=2 codes)of the total evidence being significantly positive75,76and 33%(n=1 code)being coded as inconclusive.74The evidence for secondary schools was mixed,with 1 code being negative71(50%)and 1 code being inconclusive70(50%).A single code indicating positive evidence was reported for combined primary and secondary schools.62

3.3.7.Physical environment

Two policy actions were identified in 8 studies62-67,77,78for the policy area“Physical environment”,representing 10%(n=8 codes)of the total evidence.These included the 2 following areas:(a)“Provide non-fixed PA equipment”,which received a single untested code for primary schools,63and(b)“Maximize access to physical spaces for PA”,which had 3 codes for primary schools(66%positive64,65,33%inconclusive67),two for secondary schools(50% positive(boys only)78,50% untested77)and two for combined settings(100%inconclusive).62,66

3.3.8.SUAs

A single policy action was identified in 2 studies77,79for the policy area for SUAs—“Provide PA programs in shared space”—representing 2%(n=2 codes)of the total evidence.This action is in contrast to simply opening the facility’s space without running a structured program.Both studies reported an increase in use of the space and more MVPA within school grounds when a PA program was combined with an SUA.

3.3.9.AST

A single policy action was identified in 2 studies66,67for the policy area“AST”,representing 2%(n=2 codes)of the total evidence.This action encourages schools to“Provide AST infrastructure/program”.However,no studies provided conclusive evidence linking AST policy with PA outcomes,nor did they report on the impact of school policies to promote AST in secondary schools.A study combining data from both primary and secondary schools reported that AST policies are prevalent in secondary schools,yet the evidence for their impact was inconclusive.66

3.3.10.Surveillance

Two policy actions were identified in 3 studies65,70,80for the policy area“Surveillance”,representing 4%(n=3 codes)of the total evidence.The 2 actions are:(a)“Establish a national school PA surveillance system”,for which there was a single untested code in the combined primary and secondary school setting80and(b)“Implement school PA performance reporting/award”,which had a significantly positive code for primary schools65and an untested code for secondary schools.70

4.Discussion

This review builds on existing knowledge25and is the first review to examine systematically the status of published scientific evidence,using empirical studies complemented with additional sources of evidence,on the impact of school policies on PA-related outcomes.The overall intent of policy is to provide the framework in which programs or environmental changes are implemented,thus eventually leading to higher levels of PA.The process of studying the school setting revealed 9 policy areas,several of which have been described in previous reviews,book chapters,and other types of documents,such as scientific statements and position papers(Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).However,our review presents,for the first time,the status of the scientific evidence on 22 policy actions under these policy areas.For some areas there is good support(e.g.,PE),while evidence of effectiveness is lacking or inconclusive for other areas(e.g.,surveillance).This makes it difficult at this stage to identify precisely the indicators and best practice benchmarks for evidence-based policy actions.

Strong support was found for a mandated minimum PE time.61,72This policy approach is welcome due to its potential to reduce disparities across schools.43,41Indeed,targets of 225 min per week(secondary)and 150 min per week(primary;Society for Health and Physical Educators),81or 6%-8%of all taught time,82have been recommended.Enforcing regulations requiring professional licensure of PE teachers is supported by our review and other research81adding weight to the role of the PE specialist as a PA ambassador for schools.Similarly,we found evidence of effectiveness for policies requiring adherence to PE standards and regular evaluation of PE outcomes,which provides support to current guidelines advocated by national and international organizations regarding the delivery of quality PE.24

Pertinent to prescribing any school-based PA policy is the relative complexity of promoting participation for all.40,45Youth sport programs have been advocated as a strategy to promote PA and prevent obesity.42In school sport,2 delivery models(IM and IS,which exist primarily in the United States)were found to have benefits and drawbacks.While participation in sport was found to be roughly equal between genders under the IS model,it was higher amongst boys under the IM model.58This may be due to the unrestricted nature of participation in IM sports,which may be more favorable to participation by boys.60Our findings also suggest that an IM model may exacerbate sex-based sport participation disparities due to the element of self-segregation,since girls may be less willing to participate when boys are present.58This does not limit the importance of other sociological issues pertinent to the persistent sex and gender inequities in sport,such as the social construction of girls as less capable or somehow inferior to boys.83However,the same studies note that the IM model may be superior to the IS model for increasing sport participation for all students,and specifically for ethnic minority or students of low-socioeconomic status.Also,the IM model was associated with more positive PA-related outcomes than the IS model.The reasons underlying these differences need to be further investigated,and they caution against a one-size-fits-all approach to policy.To develop a more realistic view on the potential of the sports/extracurricular policy area,the range of policy options evaluated needs to be expanded.Negative evidence for IM67policy in primary schools was found,but positive evidence for before-or after-school PA opportunities65,68,69and free-play activities64,65was reported.These findings support the existing research emphasizing the multiple benefits of unstructured,child-directed free-play activities in school settings.84

Additional policy areas for opportunities to promote PA in both primary and secondary schools include minimum duration of break times and using policy to provide youth with access to PA physical spaces that maximize the impact of the school’s physical environment.77-79Cross-curricular integration of PA into non-PE classroom time was supported in primary schools,for example,through the use of math and language classes.82Evidence suggests that school sport and PA facilities are under-utilized during after-school hours and on weekends,which limits the potential of these existing assets to encourage and facilitate PA participation among children and the wider community.77Fittingly,our review found that opening school facilities to local communities through SUAs resulted in more adults and children using these facilities outside of school hours and was positively associated with PA in primary and secondary schools in under-resourced communities when supported with good-quality PA programs.79Policy actions identified under the related areas of physical environment and SUAs provide evidence that the school environment offers considerable potential for increasing PA for everyone.

Active transport,which has been the focus of a separate PEN systematic literature review,is an area where PA policies can have a promising impact.40-43,81Indeed,other reviews85-88have attempted to address the issue of effectiveness of active transport policies as part of the Active Living by Design Community Action 5P(preparation,promotions,programs,policy influences,and physical projects)Model.Documented positive effects supporting the use of policy action as a necessary condition for active transport effectiveness were found in urban design,transport and community settings89,90rather than in school settings,where preparation,promotion and programs were prioritized.85,91This is consistent with our review,which found limited,inconclusive evidence for AST policy actions within the school setting.67Over the last 40 years in the United States,schools have increasingly been built in sparsely populated areas,away from residential areas.92Distance to school has been identified as a strong factor influencing levels of active transport.93,94Thus while statelevel policymakers may influence active transport policy,the ability of individual schools to impact levels of active commuting by students is limited if the physical environment,external to the school,is unsupportive.94,95In addition to policy,pursuing inter-sectoral partnerships with stakeholders in areas such as transport,planning and urban design is an important option for supporting changes in active transport to school.95

Our review revealed methodological issues within the literature and this should be taken into account when interpreting the results.Previous reviews have noted the importance of distinguishing policies from interventions.28,30However,our review demonstrates that work in this area may be hampered by a number of conceptual issues and ambiguity surrounding the definition of policy or policies.This was evident in studies that assessed policies that were in some cases not clearly identified or were only vaguely defined.61,78For example,Hunter and colleagues78declared that“none of the schools made any policyrelated changes”,but some of the strategies described by Hunter et al.met the definition of policy we used in our review.

Multi-level,multi-component approaches to the promotion of PA have been recommended.35,96Several multi-component interventions that had a“policy”component progressed to full-text review(Supplementary Tables 1 and 2)but were ultimately excluded from our data synthesis due to a lack of clarity in attributing evidence of impact on PA to policy.48-56For example,the Power Up for 30(PU30)study included a“voluntary commitment to 30 min of PA outside of PE”and a“needs assessment of baseline PA opportunities”.49The former is an action that is interesting to policymakers(school administrators),but the latter is an example of an individualized approach.This makes it difficult to declare with certainty whether a particular component of the intervention is effective.97Multi-component interventions rarely included robust process evaluation,rendering it impossible to determine the actual effect of the policy component.To further compound matters,it was common practice in some studies and reviews to pool and examine together the effect of environmental and policy actions or strategies(e.g.,Khan and colleagues46),when,in fact,these actions did not necessarily share the same characteristics and modus operandi.

Underlying these conceptual difficulties is the fact that schools are complicated autonomous systems and that while national or regional efforts may catalyze supportive policy environments,the translation of such policies into practice is far from simple,which supports the complexity of the policy process.A clear example of this perspective is the COMPASS study,which aims“to examine how naturally occurring changes to school PA policy,recreational programming,public health resources,and the physical environment impact adolescent MVPA”.78

Only a handful of studies included in our review used measures to assess the extent to which policies were implemented as originally intended.24,46,71,72Although the results regarding the effects of accounting for this circumstance in the analyses were mixed,a greater emphasis on using appropriate tools to assess systematic fidelity to policy implementation is warranted in order to advance knowledge in this area.98Hence,while the research into how policies can increase PA through the school setting may be useful,evidence of effective strategies for increasing implementation and compliance with established mandates is needed.Our understanding of how a degree of flexibility can be accommodated to allow for local interpretation and adaptation without compromising impact needs further investigation.Policy cycle models that differentiate between policy content and policy implementation could provide a useful theoretical framework for future analyses.99

Similarly,strong process evaluation protocols are necessary to allow researchers to gain an enhanced understanding of the barriers and facilitators to successful implementation of PA policies in the school setting.In particular,process evaluations including a robust qualitative component are needed to provide a more holistic understanding of interventions.100Coupled with providing richer information on the context in which policies take place,collecting qualitative data on the participants’and stakeholders’responses to the policies can also help researchers address the question of how policies work,which is complementary to,and equally important as,the more commonly asked question of which policies work.39

There is considerable debate in the literature concerning the nature of the evidence required to understand what works to encourage people to increase their level of PA.For example,Broekhuizen and colleagues98strongly advise researchers to conduct larger randomized controlled trials that investigate environmental interventions(e.g.,modifications to school playgrounds)in order to draw conclusions that are more valid.On the other hand,Tones101caution against the inappropriate use of a randomized controlled trial study design in health promotion,as adopting a public health perspective.Messing and colleagues35advocate for the use of different study designs,such as pragmatic or hybrid trials,that allow for the simultaneous testing of both efficacy and effectiveness.These designs,researchers argue,could allow accelerating scale-up processes of PA interventions with children and adolescents.102Similarly,Abu-Omar and colleagues85called for increasing efforts to conduct natural experiments that investigate the effectiveness of policy and environmental approaches to PA promotion.This position is consistent with the view that in order to investigate the effects of policy changes,non-randomized studies103and studies using difference-in-differences approaches might be useful.Likewise,it might be appropriate to use propensity scores,synthetic control approaches,or regression discontinuity,instrumental variables or near-far matching approaches that address unobserved confounders by utilizing quasi-random variations.104

Strengths of this review include the specific focus on schoolbased policies that have a direct or indirect impact on PArelated outcomes rather than a traditional broader focus on school-based strategies that promote PA.Reliance on empirical studies that analyze primary data,complemented with additional sources of evidence(e.g.,different types of reviews,scientific statements,position papers),is another clear strength of our review because we are able to provide a holistic and more nuanced view of the existing evidence for the impact of schoolbased policies on PA outcomes.Policies made at the national,regional,local,and school level are all included in our review,thus providing a more comprehensive view on the topic.

Our review has some limitations as well.Only literature published in the English language was included.Thus,much of the evidence we reviewed came from studies conducted in only a few countries,the US in particular,and therefore it may not be applicable in other geographical,cultural,and political settings without appropriate translation to local realities.We focused on policies that promoted PA within the school setting because other settings,such as transport and sport,are covered in separate PEN reviews.One paper61we used for data synthesis included a review of sport policy in private schools.Whilst we acknowledge that differences exist between private and public schools,we felt that this paper merited inclusion because information comparing different sport policies is limited and this study contributed knowledge to this area.There are also limitations stemming from liberal and ambiguous use of the term“policy”in the literature.Likewise,there was considerable heterogeneity regarding methodological aspects of the studies,such as research designs,assessment procedures,and types of outcomes reported,which created challenges when attempting to make coherent sense of the existing evidence.Similarly,“statistical significance”,as reported in the studies and coded in our review for synthesis purposes,is not necessarily synonymous with“practical significance”in terms of potential for impact in the real world.

5.Conclusion

There is a consensus that schools represent an ideal setting for the promotion of PA and that policy changes are needed to address the current issues of inactivity that affect children and adolescents around the world.Although work in this area is incipient and the evidence remains largely scattered,our review has identified 9 policy areas,with specific policy actions within each area,that add to the emerging body of knowledge regarding the impact of school-based policies on PA-related outcomes.The policy areas and specific policy actions provide a template to guide upstream PA promotion practice in the school setting.Policy areas with stronger evidence of PA impact were PE,school sport,classroom-based PA,active school breaks,and SUAs.However,the range of policy options implemented and evaluated in the school setting remains limited,and more attention needs to be paid to how policies are implemented and the consequent impact on the PA outcomes investigated.We recommend that there be greater clarity surrounding policy terminology,that the range of policy actions implemented within each of the identified areas be expanded and that robust and flexible evaluation methods appropriate to the real-world nature of policies be used.Finally,the impact of the context in which policies are implemented,exemplified by differences in the observed effects of some policies at the primaryvs.secondary school levels,needs to be more clearly understood.Encouraging children and adolescents to participate in PA by means of policies implemented in the school setting is an area ripe for applied and conceptual or theoretical work,especially because it concerns the effects of public policies at the regional or national level over policies implemented at local level.

Acknowledgments

The PEN project is funded by the Joint Programming Initiative(JPI)“A Healthy Diet for a Healthy Life”,a research and innovation initiative of EU member states and associated countries.The funding agencies supporting this work are(in alphabetical order)Germany:Federal Ministry of Education and Research(BMBF);Ireland:Health Research Board(HRB);Italy:Ministry of Education,University and Research(MIUR);New Zealand:University of Auckland,School of Population Health;Norway:Research Council of Norway(RCN);Poland:National Centre for Research and Development(NCBR),and the Netherlands:the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development(ZonMw).Additionally,the French partners acknowledge support through the Institute National de la Recherche Agronomique(INRA).

Authors’contributions

CBW was responsible for project administration,conceptualization,methodology,writing original draft,review,and editing;KV,JL,JZ,PG,SF,SM,and EGB were involved in conceptualization,and carried out methodology,writing original draft,review,and editing;LK carried out methodology,writing original draft,review,and editing;BC carried out writing,review,and editing.All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2021.01.006.

杂志排行

Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- A critical review of national physical activity policies relating to children and young people in England

- State laws governing school physical education in relation to attendance and physical activity among students in the USA:A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Handgrip strength and health outcomes:Umbrella review of systematic reviews with meta-analyses of observational studies

- Is device-measured vigorous physical activity associated with health-related outcomes in children and adolescents? A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Conceptual physical education:A course for the future Charles B.Corbin

- The impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on physical activity in U.S.children