Clinicopathological features and prognostic factors associated with gastroenteropancreatic mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasms in Chinese patients

2021-04-13YuChenHuangNingNingYangHongChunChenYuanLiHuangWenTianYanRuXueYangNanLiShanZhangPanPanYangZhenZhongFeng

Yu-Chen Huang, Ning-Ning Yang, Hong-Chun Chen, Yuan-Li Huang, Wen-Tian Yan, Ru-Xue Yang, Nan Li,Shan Zhang, Pan-Pan Yang, Zhen-Zhong Feng

Abstract

Key Words: Mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasm; Mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma; Prognosis; Gastro-entero-pancreatic tract

INTRODUCTION

Mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNEN) comprise a group of extremely rare heterogeneous tumors, accounting for > 5% of all gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors[1]. However, their prevalence might be largely underestimated due to diagnostic limitations and insufficient scientific understanding[2]. This type of tumor is characterized by a mixture of neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine components, each accounting for > 30% of the tumor. The most common combination is a mixture of adenocarcinomas and neuroendocrine carcinomas, defined as mixed adeno-neuroendocrine carcinoma (MANEC) in the 2010 version of the World Health Organization (WHO) digestive system tumor classification. Although nonneuroendocrine components are usually adenocarcinomas, they can also be squamous cell carcinomas, sarcomas, or other types of tumors[3-5]. The 2019 edition of the WHO digestive system classification categorizes MANEC as MiNEN, which comprises a mixture of other types of tumors and neuroendocrine neoplasms, and thus comprehensively describes the potential biological entities that constitute this tumor[4].

MiNEN have been identified in the stomach, intestines, pancreas, biliary tract,appendix, and cervix. The clinical manifestations, treatment, and prognosis of this type of tumor are not clear due to a dearth of reports[4,6-8]. We retrospectively analyzed the clinicopathological data of 46 patients with gastroenteropancreatic MiNEN (GEPMiNEN) and identified risk factors that influence prognosis. We also compared prognostic differences between GEP-MiNEN and gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NET), neuroendocrine carcinomas (NEC), and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma to improve the understanding of GEP-MiNEN and to guide future clinical treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

We searched the pathological databases of the First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College (Bengbu, China) using the following keywords: Mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma, MANEC, mixed neuroendocrine nonneuroendocrine tumor, and MiNEN between January 2013 and December 2017, and limited the tumor site to the gastrointestinal tract and the pancreas. We retrieved data on 46 patients who matched the diagnostic criteria. Two senior pathologists reviewed and categorized these patients according to the current diagnostic criteria for MiNEN as defined by the WHO (2019). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College (No. 2020057). All patients provided written informed consent to use their clinical data.

Inclusion criteria

The WHO (2019) classifies MiNEN as tumors of the digestive system characterized by presence of neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine components, each accounting for> 30% of the tumor[4]. The inclusion criteria were as follows: All patients were treated surgically, including by endoscopy and laparotomy; the postoperative pathology was diagnosed as MiNEN by two senior doctors; the tumor was in the stomach, intestine,or pancreas, and the patient had no history of other malignant tumors; and preoperative radiotherapy or chemotherapy had not been administered.

Methods

Tumor tissues were fixed with 10% neutral formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin,sliced into 4 μm-thick sections, and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The sections were histologically analyzed using a light microscope. Tumors were clinically staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (8thedition).

Sections were immunohistochemically analyzed using the EnVision method with the following primary monoclonal antibodies for Ki-67 (mouse anti-human antibody,clone MIB-1), cluster of differentiation (CD) 56 (mouse anti-human antibody, clone 56 C04), synaptophysin (rabbit anti-human antibody, clone SP11), and chromogranin A(CgA; rabbit anti-human antibody, clone SP12) (all from Maixin Biotechnology Co.,Ltd., Fuzhou, China). Ki-67 staining revealed brownish-yellow granules in the nuclei of tumor cells, and ≥ 20%, 21%-50%, and ≥ 51% stained nuclei were regarded as immunohistochemically positive, low expression, and high expression, respectively.The CD56 signal was observed on cell membranes, whereas Syn and CgA signals were located in the cytoplasm. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time elapsed from the date of surgery to the date of death or the end of follow-up.

Follow-up

Follow-up was conducted for 46 patients by either reviewing their information files,making phone calls, or sending out e-mails from the date of diagnosis until December 31, 2019. The OS of the patients who survived or were lost to follow-up was excluded at the date of their last follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Data were statistically analyzed using statistic package for social science 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Categorical and continuous variables were analyzed using chi-square tests and independent-sample t-test, respectively. Survival was assessed using univariate Kaplan-Meier analysis and survival curves. Survival rates between groups were compared using log-rank tests, and OS rates were analyzed using multivariate Cox regression models. Values with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical methods were reviewed by Lian-Guo Fu from Bengbu Medical College.

RESULTS

Clinicopathological information of patients

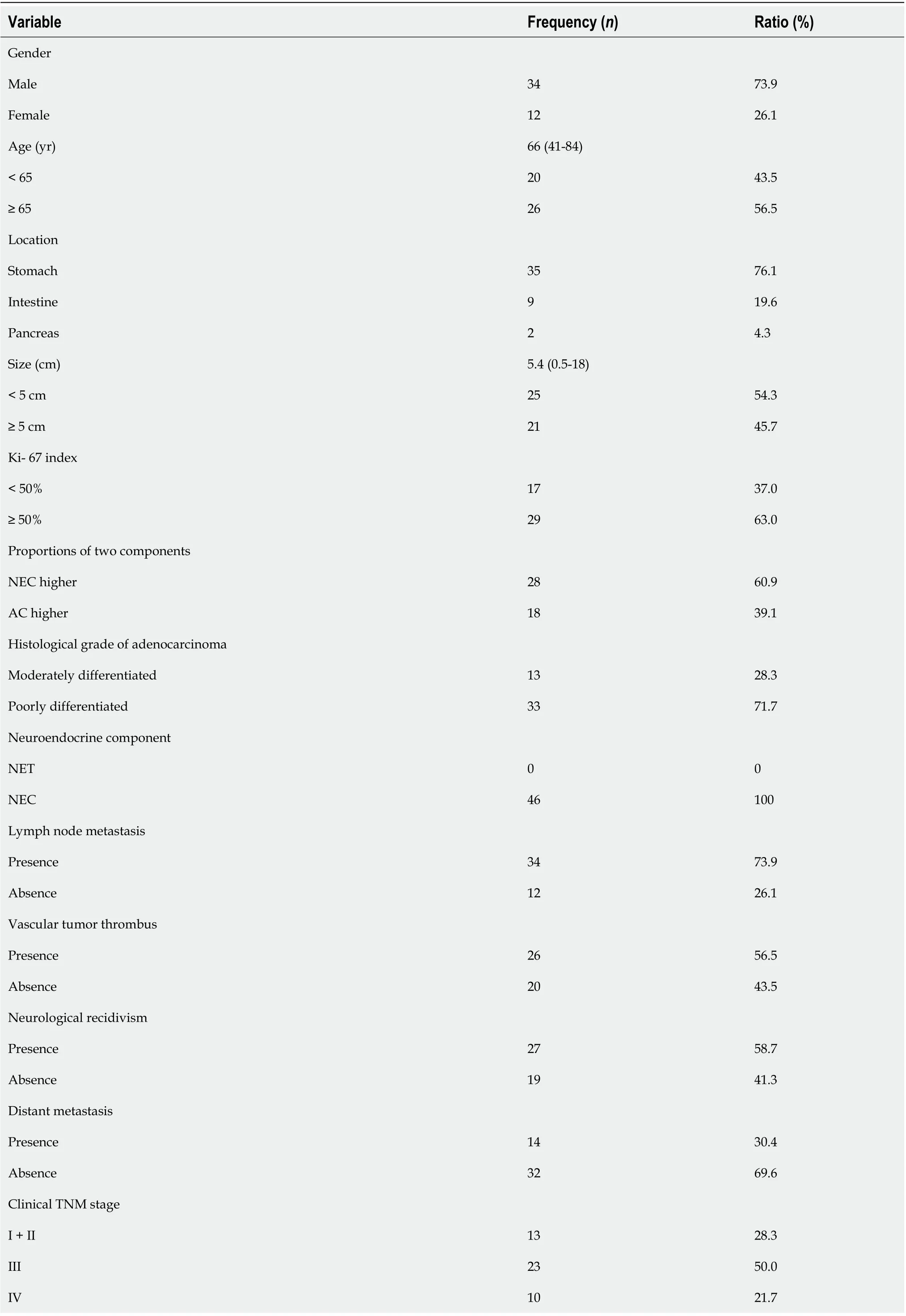

The clinicopathological data of 46 patients (males, n = 34; male-to-female ratio, 2.83: 1;average age, 65 (41-84) years; median age, 66 years) with GEP-MiNEN were analyzed.Among the forty-six patients, thirty-five patients had gastric tumors, nine had intestinal tumors, and two had pancreatic tumors. The tumor diameter was ≥ 5 and < 5 cm in 29 and 17 patients, respectively. Microscopy revealed a significant proportion of tumors categorized as NEC and as adenocarcinoma in 28 (60.9%) and 18 (39.1%)patients, respectively. Nerve invasion and vascular tumor thrombus were evident in 27 (58.7%) and 26 (56.5%) of the 46 patients, respectively. Furthermore, 34 (74.0%) of the 46 patients had lymph node involvement, and 14 (30.4%) had distant metastasis.Tumors metastasized to the liver in thirteen of these fourteen patients (three tumors were discovered during surgery), and to the ovary in one patient (Table 1).

Microscopic and immunohistochemical features

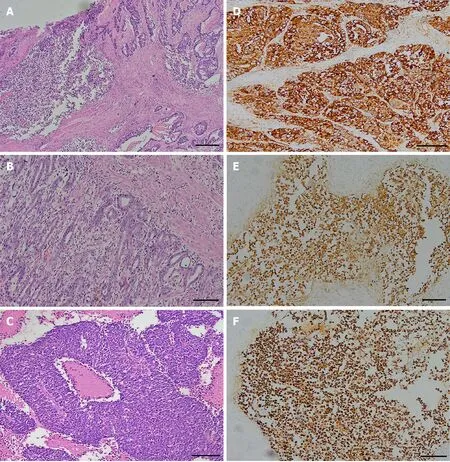

The 46 patients exhibited GEP-MiNEN comprising medium or poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma combined with neuroendocrine carcinoma (Figure 1 A). Among them,thirty-three had poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and four had mucinous adenocarcinomas. In 13 patients with moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, the neuroendocrine component was NEC G3. The adenocarcinoma in these patients had an irregular papillary, adenoid, sieve, or nested distribution, and cells had round or oval nuclei, and coarse and granular chromatin (Figure 1 B). The neuroendocrine carcinomas were nested, with an organoid-like distribution, and comprised small cubic or cylindrical tumor cells with round nuclei, reduced cytoplasm, an increased nucleoplasm ratio, and fine nuclear chromatin (Figure 1 C).

The adenocarcinoma components expressed cytokeratin (Figure 1 D), and most did not express neuroendocrine cancer markers. The neuroendocrine cancer components expressed CgA, Syn, and CD56. All patients were positive for CgA (Figure 1 E), 35 were positive for Syn (76.1%) (Figure 1 F), and 32 were positive for CD56 (69.6%). The Ki-67 proliferation index was > 50% (high expression) and < 50% (low expression) in 29 and 17 patients, respectively.

Follow-up and survival analysis

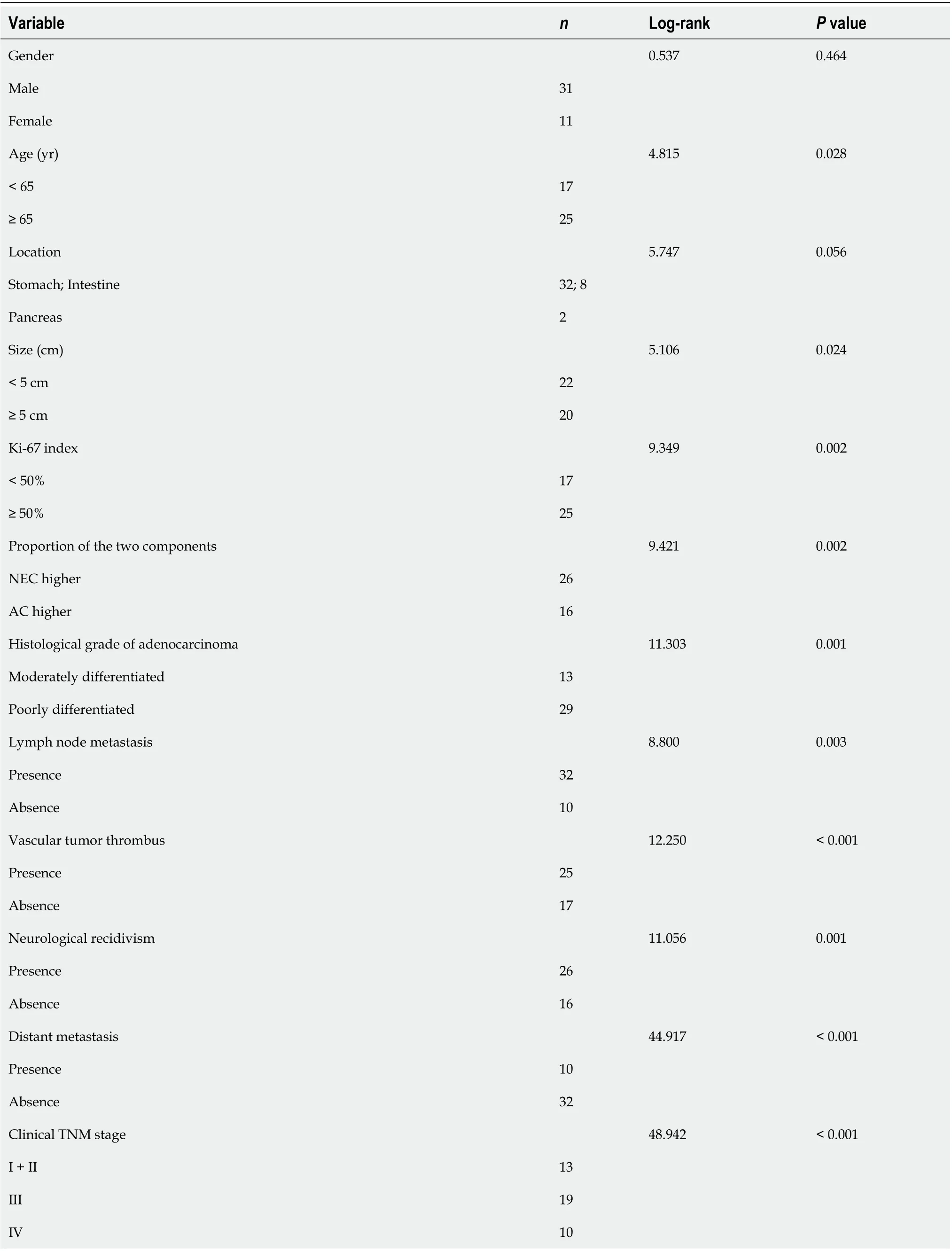

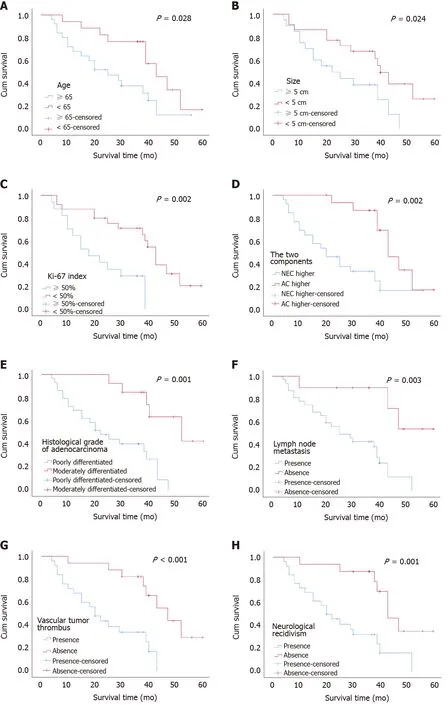

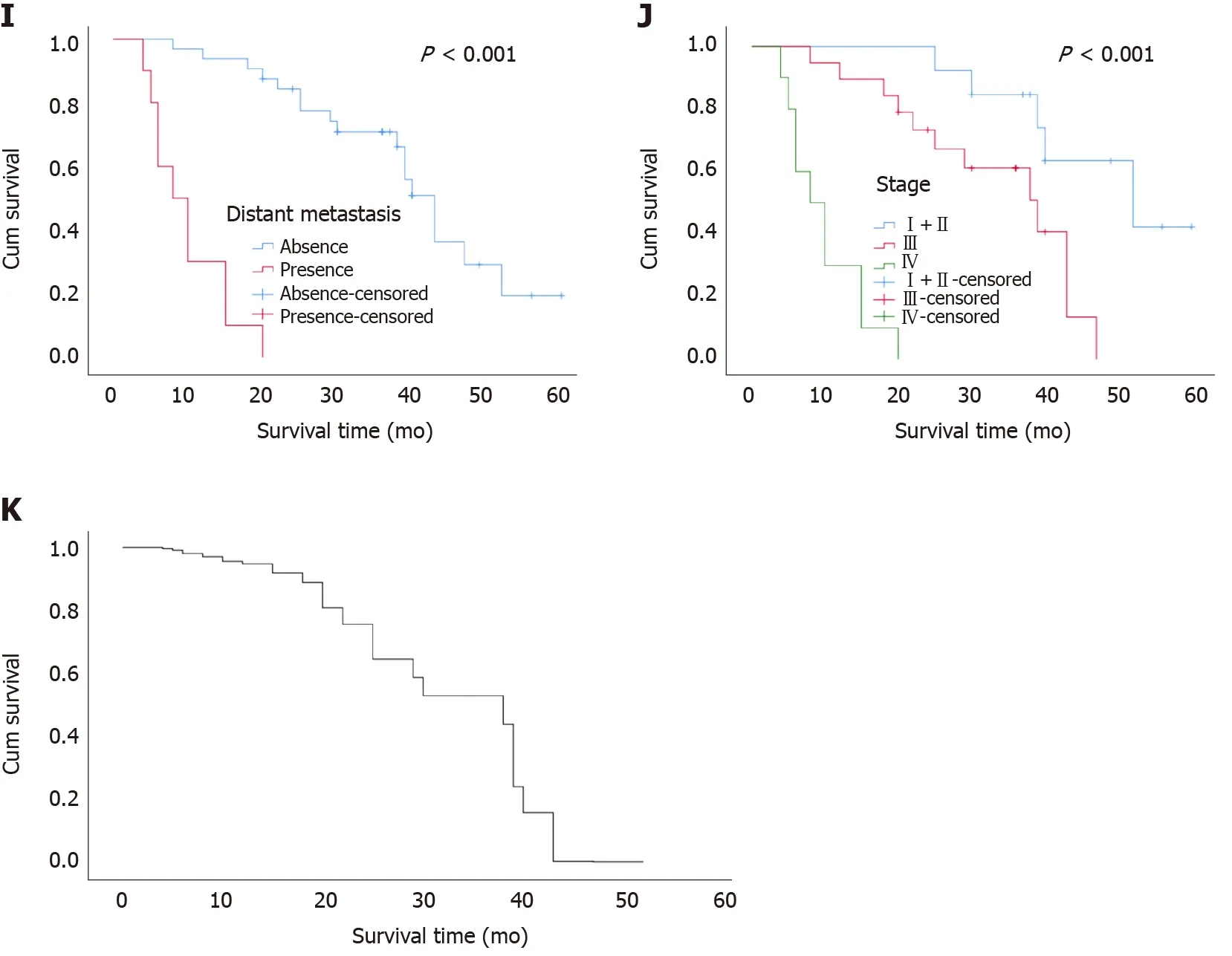

Follow-up was conducted for the patients for a median of 39 (11-72) mo. As of December 31, 2019, a total of forty-two cases were subjected to follow-up and four cases were lost to the follow-up process (8.7%). By the end of the follow-up process, 27 patients had succumbed to tumor-related death. The average and median survivals were 28.60 ± 15.14 and 30 mo, respectively (range, 12-43 mo). Univariate analysis using log-rank tests indicated that the age of the patients, tumor size, Ki-67 index, tumor composition (proportion of neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine tumor), degree of adenocarcinoma differentiation, lymph node involvement, vascular tumor thrombus, neurological recidivism, distant metastasis, and clinical stage were associated with OS (P < 0.05). Table 2 and Figure 2 A-J respectively show the results of univariate analysis of survival and survival curves. Patients aged ≥ 65 years with a tumor diameter ≥ 5 cm, a Ki-67 index ≥ 50, high NEC, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, lymph node involvement, vascular tumor thrombus, nerve invasion,distant metastasis, and high clinical stage had a reduced OS. Sex (P = 0.464) and tumor location (P = 0.056) were not significantly associated with OS.

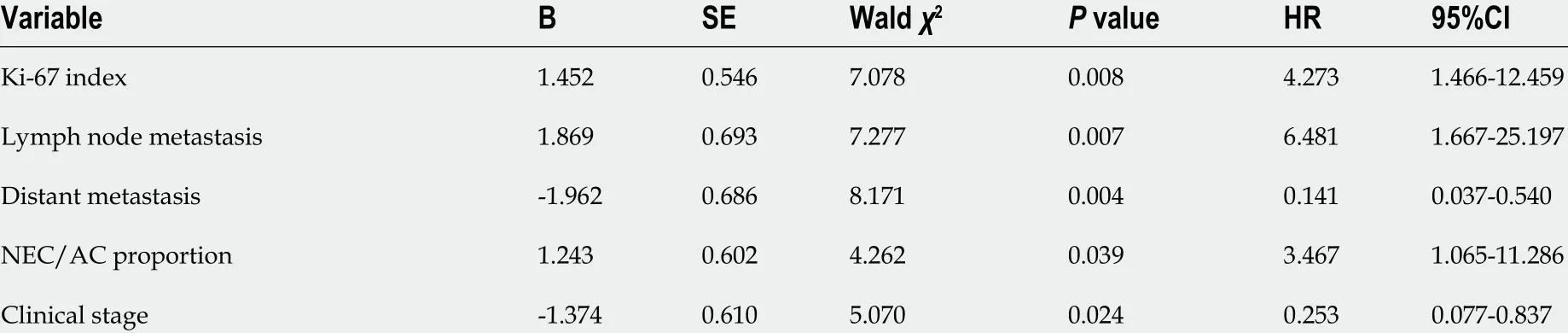

Meaningful indicators in the univariate analysis were included in the Cox regression analysis, and the results showed that Ki-67 index ≥ 50% (P = 0.008), lymph node involvement (95%CI: 1.667-25.197, P = 0.007), distant metastasis (95%CI: 0.037-0.540, P = 0.004), increased proportion of NEC (P = 0.039), and clinical stage (P = 0.024)were independent risk factors that affected the OS of patients with GEP-MiNEN(Figure 2 K and Table 3).

Comparative analysis of GEP-MiNEN, NET, and NEC

We selected 55 patients [males, n = 24; average age at diagnosis, 49 (11-85) years] with gastrointestinal pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NET) in the intestine (n = 39),

pancreas (n = 9), and stomach (n = 7). The average tumor size was 1.7 cm. Lymph nodes were involved in 13 patients, and two had distant metastasis (the small intestine was the primary site of all tumors; one case metastasized to the liver and the other to the pancreas). Eight of the fifty-five patients were lost to follow-up. Tumor location,lymph node involvement, and distant metastasis significantly differed between patients with GEP-NET and MiNEN. By the end of the follow-up period, the median OS was significantly longer in the patients with NET than in the patients with MiNEN(50 mo vs 30 mo, P < 0.001).

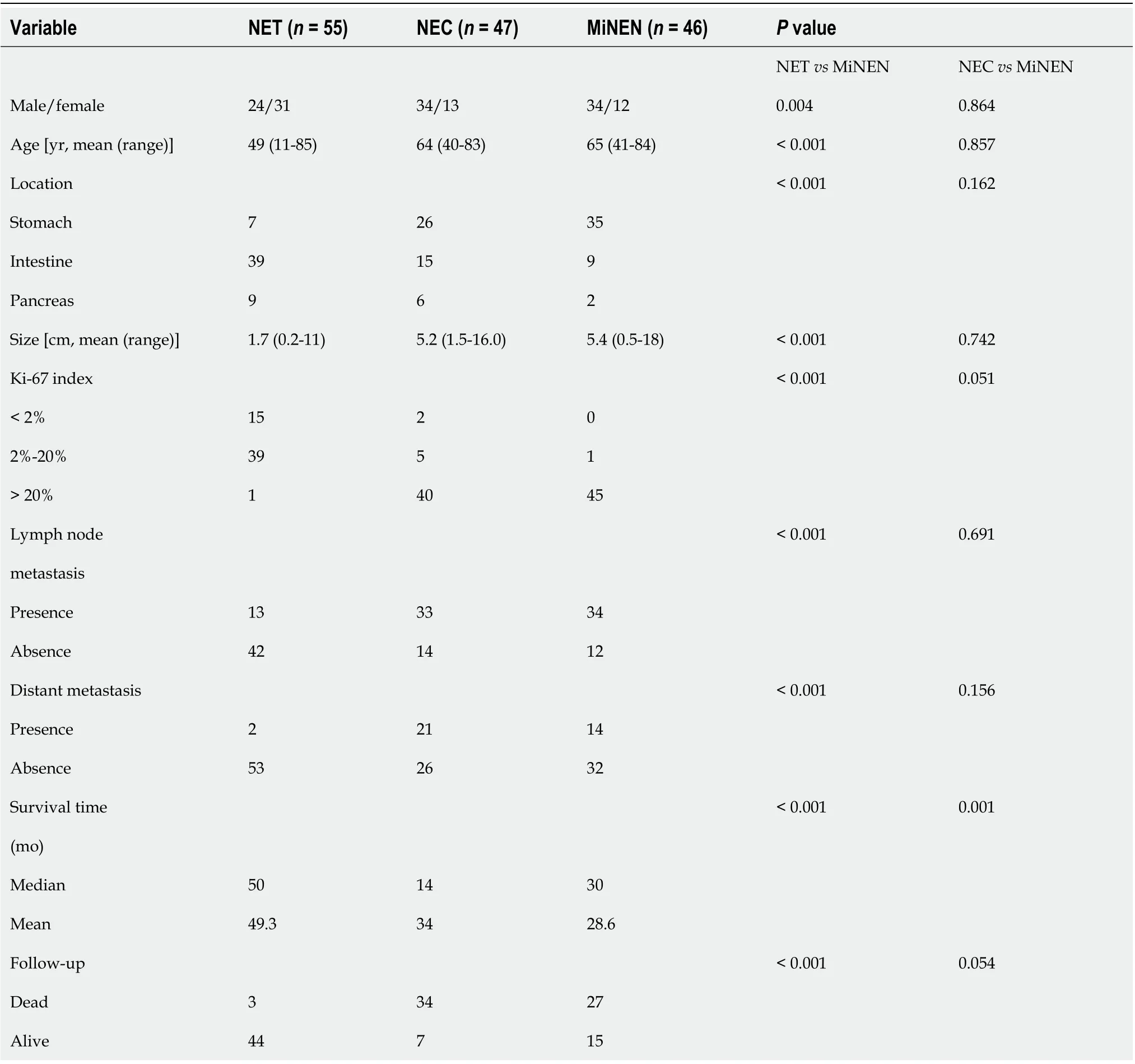

Table 1 Patients’ characteristics

We selected 47 patients [males, n = 34; average age at diagnosis, 64 (range, 40-83 years)] with gastrointestinal pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma (GEP-NEC) tumors located in the stomach (n = 26), intestine (n = 15), and pancreas (n = 6). The average tumor size was 5.2 cm. Lymph nodes were involved in 33 cases, and 21 patients had distant metastasis. Tumors metastasized to the pancreas (n = 1), to both the liver and rectum (n = 1), abdominal cavity (n = 4), and liver (n = 15). Six patients were lost to follow-up. The effects of sex, age, tumor size, tumor location, lymph node involvement, and distant metastasis on OS did not significantly differ between GEPNEC and MiNEN (P > 0.05 for all). The median OS was significantly shorter in the patients with GEP-NEC than in those with MiNEN (14 vs 30 mo, P = 0.001; Table 4).

Comparative analysis of GEP-MiNEN and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma

We selected 58 patients [average age, 61 (31-81) years; male, n = 37] with poorly differentiated gastrointestinal pancreatic adenocarcinoma located in the stomach (n =42), intestines (n = 12), and pancreas (n = 4). The tumors were < 5 and ≥ 5 cm in 25 and 33 patients, respectively. Lymph node involvement and distant metastasis were found in 47 and 16 patients, respectively. Sex, age, tumor size, tumor location, lymph node involvement, and distant metastasis did not significantly differ between the two groups (P > 0.05 for all); median OS did not differ either (30 mo vs 18 mo, P = 0.453;Table 5).

DISCUSSION

In the 2010 WHO classification of digestive diseases, MANEC is defined as “a tumor with the morphologically recognizable glandular epithelial and neuroendocrine phenotype and is defined as cancer because both components are malignant.” A mixture of squamous cell carcinoma and neuroendocrine components has also been identified in some esophageal and anal tumors[4]. At least 30% of malignancies are deemed eligible for classification as MANEC[9]. For instance, a typical adenocarcinoma without the morphological characteristics of a neuroendocrine tumor, in which immunohistochemical staining reveals scattered neuroendocrine markers, should not be diagnosed as "adenocarcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation". In 2017, the classification of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors was modified by the WHO and classified together with digestive tumors. The previous term, MANEC, was replaced by MiNEN[10]. The WHO stipulated in 2019 that the term MiNEN is applicable to all digestive tract and neuroendocrine tumors of the digestive system and that these tumors are classified as NET, NEC, and MiNEN. The MiNEN comprise nonneuroendocrine (mostly adenomas or adenocarcinomas, and rarely squamous cell carcinomas) and neuroendocrine components (NETG1, NETG2, NEC), either of which must account for at least 30% of the tumor[11,12]. While MiNEN have been found in most organs, they are usually found in the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas[5,13,14].

The diagnosis of MiNEN is primarily based on tumor cytology and structure, and neuroendocrine components can be confirmed by immunolabeling with synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and CD56[7]. The recent widespread application of immunohistochemistry has shown that MiNEN tumors are not as rare as previously hypothesized, and the morbidity and mortality rates of gastrointestinal MiNEN are constantly increasing at an alarming pace[15]. However, knowledge of MiNEN remains limited. The two cellular components of MiNEN are difficult to distinguish, especially when both are poorly differentiated, and they are often misdiagnosed as adenocarcinomas or grade 3 neuroendocrine tumors[16]. We identified MiNEN as a combination of moderately or poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and NEC.Therefore, in addition to NET, our control group comprised patients with NEC and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma.

Table 2 Univariate analysis of overall survival

Most MiNEN cases develop slowly and manifest as nonspecific clinical symptoms like those of traditional adenocarcinoma. The disease, for many patients, is usually in its advanced stages by the time when a physician is consulted, and most demonstrate lymph node and distant metastasis, indicating that most conventional adenocarcinoma cases with MiNEN are characterized by aggressive behavior and a poor prognosis[7,16].The GEP-MiNEN tumors analyzed herein were most prevalent in the stomach of the 46 patients, followed by the intestine and pancreas. We found that 58.7%, 56.5%,74.0%, and 30.4% of the patients had nerve invasion, vascular tumor thrombus, lymph node involvement, and distant metastasis, respectively. The most common site of distant metastasis was the liver [13 (28.3%) of 46]. Lymph node involvement (P =0.007) and distant metastasis (P = 0.004) were independent risk factors for the OS of patients. These results suggest that MiNEN cases have significant invasive potential.

Nie et al[17]suggested that the degree of differentiation of the adenocarcinoma and the neuroendocrine cancer cells of gastric MANEC affect prognosis. A lower degree of cancer cell differentiation was associated with a worse prognosis. The prognosis of patients with gastrointestinal MANEC largely depends on the stage and type of neuroendocrine components of the tumor, suggesting that NEC components comprise a key prognostic indicator[7,14,18-20]. Park et al[21]have suggested that gastric cancer with neuroendocrine differentiation indicates a poor prognosis, and the degree of such differentiation can serve as an independent prognostic indicator.

The neuroendocrine components of the 46 analyzed GEP-MiNEN were NEC G3,and the adenocarcinomas were either moderately differentiated or poorly differentiated. The median OS was significantly shorter for patients with poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, compared to that observed in those with moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (20 mo vs 40 mo, P = 0.001). Furthermore, the median OS was significantly shorter in patients with major NEC compared to that in patients with major adenocarcinoma (20 mo vs 43 mo, P = 0.002). Multivariate analysis selected major NEC as an independent risk factor for OS (95%CI: 1.065-11.286, P = 0.039). This further shows that the degree of adenocarcinoma differentiation and the proportion of NEC severely impact the survival and prognosis of patients, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies[2,17,18,22,23].

Xie et al[19]examined 80 patients with gastric MANEC and associated a Ki-67 index ≥60% with poor survival and higher recurrence rates. Milione et al[23]have reported that the Ki-67 index of the NEC component is the most powerful prognostic indicator, and that the risk of death is 8 -fold higher in patients with Ki-67 ≥ 55% than in those with Ki-67 < 55%. The median OS of our patients was significantly shorter for patients with a Ki-67 index ≥ 50% than for those with a Ki- 67 index < 50% (25 mo vs 43 mo, P =0.002). In line with previous studies, we also identified the Ki-67 index as an independent prognostic indicator of OS (95%CI: 1.466-12.459, P = 0.008).

Among the 46 patients examined herein, 33 (71.7%) had clinical stages III and IV GEP-MiNEN at the time of diagnosis. By the end of the follow-up, 22 of these 33 patients succumbed (within an average of 20.13 mo). The median OS was significantly shorter for patients with stages III and IV, compared to that in patients with stage I + II tumors (20 mo vs 40 mo, P < 0.001). Multivariate analysis showed that clinical stage was an independent risk factor for the OS of the patients (95%CI: 0.077-0.837, P =0.024), which was consistent with the findings of the study by Song et al[24]. Our findings were in line with those of a previous study in which a prognostic model based on tumor node metastasis staging combined with tumor composition ratio and Ki-67 index achieved a similar discriminative ability[19].

Brathwaite et al[16]found that the prognosis was worse for MANEC than conventional adenocarcinoma and low-grade neuroendocrine tumors. Others[22]have suggested that the prognosis of gastric MANEC is worse than that of gastric adenocarcinoma. However, whether the prognosis is better for patients with gastric MANEC than NEC patients is not clear. One study found no significant differences in survival between patients with gastric and colorectal MANEC and NEC[25]. Watanabe et al[26]found that disease-free survival and OS rates were significantly lower among patients with MANEC than patients with adenocarcinoma. The prognosis of patients,especially those with stage III MANEC, is as poor as that of NEC patients compared with colorectal adenocarcinoma. La Rosa et al[27]suggested that MANEC tumors containing well-differentiated NET and adenocarcinoma components should be regarded as adenocarcinomas, while MANEC tumors containing poorly differentiated NEC components should be regarded as NEC.

We found that 34 (74.0%) of the 46 patients with MiNEN had lymph node involvement, which was slightly more than the 33 (70.2%) of the 47 patients with NEC.However, distant metastasis was more prevalent in patients with NEC than in thosewith MiNEN [21 (44.7%) of 47 vs 14 (30.4%) of 46], which was consistent with previous findings[6,28]. Furthermore, the metastatic behavior of the two types of tumors might differ; MiNEN usually involve regional lymph nodes, while NEC frequently exhibit distant metastasis, suggesting that NEC are more aggressive. We found that the median OS was significantly longer for patients with MiNEN than those with NEC (30 mo vs 14 mo, P = 0.001).

Table 3 Multivariate Cox regression analysis results of overall survival

Few reports have described the prognosis of patients with MiNEN and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. Among forty-two of the forty-six patients with GEPMiNEN who had complete follow-up data, fourteen had distant, thirteen had liver,and one had ovarian metastases. Among the 50 out of the 58 patients with poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma who had complete follow-up data, 16 developed distant metastases to the liver (n = 10), abdominal cavity (n = 4), and ovaries (n = 2),where a Klugenberg tumor formed. Sex, age, tumor size, tumor location, Ki-67 index,lymph node involvement, distant metastasis, and clinical stage did not significantly differ between patients with MiNEN and those with poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (P > 0.05 for all). Furthermore, median OS did not significantly differ between these patients (30 mo vs 18 mo, P = 0.453).

Although the histological origin and molecular mechanism of MiNEN remain controversial, the findings of the existing molecular and genetic studies on MiNEN of the digestive system have shown that neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine components share a common monoclonal origin[29-32]. The origin of MiNEN is associated with mutations in MiNEN-related genes, including TP53, BRAF, and KRAS[2,16,25], of which the TP53 mutation is the most common[29]. Milione et al[23]showed a higher frequency of chromosomal and genetic abnormalities in neuroendocrine,compared to that in non-neuroendocrine components, indicating that nonneuroendocrine progression to a neuroendocrine cellular phenotype was more frequent than previously thought. Microsatellite instability might be a driving factor for the development of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors[16]. Conventional colorectal adenocarcinomas and MANEC might have a common genetic profile[25], and might respond to chemotherapy for colorectal adenocarcinoma, revealing a genetic connection between most colorectal MANEC and NET and the adenocarcinoma family.

In the absence of contraindications, the main treatment following a diagnosis of GEP-MiNEN is radical surgery. Chemotherapy is the treatment of choice for poorly differentiated, or rapidly progressing advanced tumors. Cisplatin/5-FU combined with etoposide is the most common chemotherapeutic regimen applied to treat MiNEN and is similar to those used to treat adenocarcinomas[12,31,33]. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy significantly improves the OS of patients with locally advanced NEC and MANEC in the stomach with an acceptable level of toxicity[34]. Surgical removal of each metastasis combined with systemic chemotherapy can significantly improve the prognosis of patients with colorectal MiNEN tumors that have already metastasized to distant locations[35]. An optimal combination of systemic chemotherapy and somatostatin analogs such as octreotide and lanreotide can prolong the progressionfree survival of patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors[12].

CONCLUSION

Overall, GEP-MiNEN are rare and heterogeneous tumors with a highly variable prognosis for which there are no clear treatment guidelines. Although we found aworse prognosis for patients with MiNEN than for those with NEC, it did not significantly differ from that of patients with poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma.Thus, patients with GEP-MiNEN and those with adenocarcinoma should be similarly treated. Furthermore, the treatment of any suspected or diagnosed GEP-MiNEN patient should be discussed at a multidisciplinary expert meeting to determine optimal personalized treatment for individual patients. The number of patients in the present retrospective study was limited by the rarity of GEP-MiNEN, and they were sourced from a single institution. Therefore, further multicenter, larger-cohort studies are warranted to clarify the clinicopathological features and biological behavior of GEP-MiNEN.

Table 4 Comparative of mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms, neuroendocrine tumors, and neuroendocrine carcinomas

Table 5 Comparison between patients with mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms and those with poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma

Figure 1 Histopathological and immunohistochemical findings of gastroenteropancreatic mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms. A: Neuroendocrine carcinoma (left) and adenocarcinoma (right) (Hematoxylin-eosin staining, scale bar 200 µm); B: Adenocarcinoma component(Hematoxylin-eosin staining, scale bar 200 μm); C: Neuroendocrine component (Hematoxylin-eosin staining, scale bar 100 μm); D: Cytokeratin-positive adenocarcinoma (EnVision, scale bar 100 μm); E: CgA-positive neuroendocrine (EnVision, scale bar 100 μm); F: Syn-positive neuroendocrine (EnVision, scale bar 100 μm).

Figure 2 Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival among 46 patients with gastroenteropancreatic mixed neuroendocrine-nonneuroendocrine neoplasms. Overall survival grouped by A: Age (P = 0.028); B: Tumor size (P = 0.024); C: Ki-67 index (P = 0.002); D: Proportions of NEC and adenocarcinoma (P = 0.002); E: Adenocarcinoma differentiation (P = 0.001); F: Lymph node metastasis (P = 0.003); G: Vascular tumor thrombus (P < 0.001); H:Nerve invasion (P = 0.001); I: Distant metastasis (P < 0.001); and J: Clinical stage (P < 0.001); K: Overall survival of 46 patients with gastroenteropancreatic mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNEN) are a rare tumor type. However, their prevalence might be largely underestimated due to diagnostic limitations and insufficient scientific understanding. The clinical manifestations,treatment, and prognosis of this type of tumor are still poorly understood. Our research on the risk factors, clinical manifestations, and prognosis related to this rare tumor type is of great significance for optimizing clinical treatment.

Research motivation

MiNEN associated risk factors, clinical manifestations, and prognosis must be explored to improve our understanding of this rare tumor type and optimize clinical treatment.

Research objectives

We have identified the risk factors that influence the prognosis of patients with gastroenteropancreatic MiNEN (GEP-MiNEN). We also compared prognostic differences between GEP-MiNEN and gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors,neuroendocrine carcinomas (NEC), and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma to improve the understanding of GEP-MiNEN and to guide future clinical treatment.

Research methods

This is a single-center, retrospective study. We retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of patients who were diagnosed with GEP-MiNEN. Risk factors influencing patient prognosis were assessed using Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox regression models. We compared the results with randomly selected patients with gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, NEC, and poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas.

Research results

Most GEP-MiNEN in our study were gastric tumors, a few were intestinal tumors, and a minority, pancreatic tumors. The median overall survival was 30 mo. Ki- 67 index ≥50%, high proportion of NEC, lymph node involvement, distant metastasis, and higher clinical stage were independent risk factors affecting the prognosis of patients with GEP-MiNEN. The median overall survival was shorter for patients with NEC than for those with MiNEN but did not significantly differ from those with poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and MiNEN. Thus, patients with GEP-MiNEN and those with adenocarcinoma should be similarly treated. Furthermore, the treatment of any suspected or diagnosed GEP-MiNEN patient should be discussed at a multidisciplinary expert meeting to determine optimal personalized treatment.However, the number of patients in the present retrospective study was limited by the rarity of GEP-MiNEN, and they were sourced from a single institution. Therefore,further multicenter, larger-cohort studies are warranted to clarify the clinicopathological features and biological behavior of GEP-MiNEN.

Research conclusions

A poor prognosis is associated with GEP-MiNEN. Ki-67 index, tumor composition,lymph node involvement, distant metastasis, and clinical stage are important factors for patient prognosis.

Research perspectives

In view of the limited number of patients and the short-term follow-up of our study, a larger prospective study with long-term follow-up is needed to confirm our results.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Lian-Guo Fu for significant contributions to data analysis.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Helicobacter pylori: Commensal, symbiont or pathogen?

- Simultaneous partial splenectomy during liver transplantation for advanced cirrhosis patients combined with severe splenomegaly and hypersplenism

- Effect of liver inflammation on accuracy of FibroScan device in assessing liver fibrosis stage in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection

- Quantitative multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging can aid non-alcoholic steatohepatitis diagnosis in a Japanese cohort

- Sinapic acid ameliorates D-galactosamine/lipopolysaccharideinduced fulminant hepatitis in rats: Role of nuclear factor erythroidrelated factor 2/heme oxygenase-1 pathways

- Xiangbinfang granules enhance gastric antrum motility via intramuscular interstitial cells of Cajal in mice