Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Current status of endoscopic approach and additional therapies

2021-04-08AlinaIoanaTantauAlinaMandrutiuAnamariaPopRoxanaDeliaZaharieDanaCrisanCarmenMonicaPredaMarcelTantauVoicuMercea

Alina Ioana Tantau, Alina Mandrutiu, Anamaria Pop, Roxana Delia Zaharie, Dana Crisan, Carmen Monica Preda, Marcel Tantau, Voicu Mercea

Alina Ioana Tantau, Department of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, “Iuliu Hatieganu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 4th Medical Clinic, Cluj-Napoca 400012, Cluj, Romania

Alina Mandrutiu, Anamaria Pop, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Gastroenterology and Hepatology Medical Center, Cluj-Napoca 400132, Cluj, Romania

Roxana Delia Zaharie, Department of Gastroenterology, “Prof.Dr.Octavian Fodor” Regional Institute of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Cluj-Napoca 400162, Cluj, Romania

Roxana Delia Zaharie, Department of Gastroenterology, “Iuliu Hatieganu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca 400012, Cluj, Romania

Dana Crisan, Internal Medicine Department, Cluj-Napoca Internal Medicine Department, “Iuliu Hatieganu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 5th Medical Clinic, Cluj-Napoca 400012, Cluj, Romania

Carmen Monica Preda, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Clinic Fundeni Institute, “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest 22328, Romania

Marcel Tantau, Voicu Mercea, Department of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, “Prof.Dr.Octavian Fodor” Regional Institute of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Cluj-Napoca 400162, Cluj, Romania

Marcel Tantau, Voicu Mercea, Department of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, “Iuliu Hatieganu“ University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca 400012, Cluj, Romania

Abstract The prognosis of patients with advanced or unresectable extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is poor.More than 50% of patients with jaundice are inoperable at the time of first diagnosis.Endoscopic treatment in patients with obstructive jaundice ensures bile duct drainage in preoperative or palliative settings.Relief of symptoms (pain, pruritus, jaundice) and improvement in quality of life are the aims of palliative therapy.Stent implantation by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is generally preferred for long-term palliation.There is a vast variety of plastic and metal stents, covered or uncovered.The stent choice depends on the expected length of survival, quality of life, costs and physician expertise.This review will provide the framework for the endoscopic minimally invasive therapy in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.Moreover, additional therapies, such as brachytherapy, photodynamic therapy, radiofrequency ablation, chemotherapy, molecular-targeted therapy and/or immunotherapy by the endoscopic approach, are the nonsurgical methods associated with survival improvement rate and/or local symptom palliation.

Key Words: Cholangiocarcinoma; Endoscopic drainage; Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; Photodynamic therapy; Radiofrequency ablation; Brachytherapy

INTRODUCTION

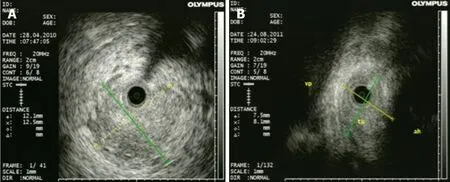

Cholangiocarcinomas (CCAs) have a very high mortality rate worldwide[1,2].Diagnosis is challenging and delayed in many cases due to the common asymptomatic clinical behavior of early-stage disease, the lack of a standardized screening protocol for earlystage disease and the limitations inherent to using CA19-9 as a cancer marker[3].The ability to achieve a definite cytopathological or histopathological diagnosis in patients with suspected CCA ranges widely in the literature from 26% to 80%[4-8].Magnetic resonance imaging plus magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography is the preferred imaging modality as it can assess resectability and tumor extent with a high accuracy[9-15].Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and fine needle aspiration guided by EUS is a useful technique in the diagnosis and staging of CCA (Figure 1 and 2) and should always be taken into consideration for CCA clinical management.For patients with obstructive jaundice, in particular, intraductal ultrasonography has been suggested for the assessment of bile duct strictures and local tumor staging[16](Figure 3).

CCAs are divided into three types: Intrahepatic CCA, distal CCA (dCCA) and perihilar CCAs (pCCA) or Klatskin tumors.The majority of CCAs are pCCAs (60%-75% of cases).dCCA is present in 15%to 25% of cases, and intrahepatic CCA accounts for 5%to 15% of cases[17-20].

Surgery is the only curative treatment for extrahepatic CCA with the goal of R0 resection.Unfortunately, only a minority of patients (approximately 35%) have early stage disease and are candidates for this curative treatment option[21].Furthermore, only a few patients with pCCA are candidates for liver transplantation following neoadjuvant chemotherapy[22].

More than 50% of patients with jaundice are reportedly inoperable at the time of first diagnosis.Locally advanced, unresectable CCA cases include patients with macroscopic residual disease following resection, locally advanced, categorically unresectable disease at presentation or locally recurrent disease after potentially curative treatment.Prognosis of these patients is poor with a median survival time of < 6 mo[23].Relief of symptoms (pain, pruritus, jaundice) and improvement in quality of life are the aims of palliative therapy.

Figure 1 Endoscopic ultrasound for liver evaluation.

Figure 2 Endoscopic ultrasound of the distal common bile duct.

Figure 3 Intraductal ultrasonography for diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma.

Each subtype of CCA has different clinical management[24].Therefore, an individualized approach is mandatory for pCCA or dCCA.In patients with extrahepatic CCA who are not candidates for surgery or liver transplantation, consideration should be given to enrollment in a clinical trial, particularly those evaluating targeted therapy[25].

Additional treatment measures in locally advanced extrahepatic CCA may include the following: Stenting, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), photodynamic therapy (PDT), radiation therapy, chemotherapy, molecular-targeted therapy and/or immunetherapy[25].

Preoperative or palliative biliary drainage using stents are two main approaches for extrahepatic CCA[26].Stents can be placedviaendoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography to relieve biliary obstruction.Stenting may relieve the jaundice and pruritus and improve the quality of life[26].In ERCP, a unilateral or bilateral plastic or metallic stent can be used[23,24,26].

RFA and PDT are effective in restoring biliary drainage and improving quality of life in patients with nonresectable disseminated extrahepatic CCA[23,27].Local radiotherapy combined with metallic stent placement is a new and efficient method in advanced extrahepatic CCA[28].Several clinical trials are evaluating the effect of specific molecular agents targeting various signaling pathways in advanced extrahepatic CCA[25].Our proposal is to highlight the utility and the efficiency of different endoscopic techniques and additional measures in extrahepatic CCA.

PALLIATION OF OBSTRUCTIVE JAUNDICE

Endoscopic treatment of CCA with obstructive jaundice ensures bile duct drainage in preoperative or palliative settings[23,26].Endoscopic procedures are the preferred palliative treatment options for patients with advanced or unresectable CCA.In patients with advanced pCCA, endoscopic biliary drainageviaERCP is more difficult than those with dCCA[23,25,26].If the transpapillary approach failed, then other procedures can be considered: Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD), endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD) or hepatico-gastrostomy or locoregional therapies including transluminal PDT and RFA[27].

Preoperative biliary drainage

There is some controversy in the literature as to how preoperative biliary drainage should be accomplished prior to laparotomy for patients with obstructive jaundice[29-30].In a European multicenter study, Goumaet al[31]showed that the postoperative outcomes in patients with pCCA who underwent surgery and preoperative biliary drainage were not improved.However, the rate of mortality was lower in patients who received en bloc right hepatectomy.In dCCA, preoperative bile duct drainage is not always necessary unless neoadjuvant chemotherapy is planned and might be associated with an increased risk of cholangitis and postoperative infectious complications[32].

Acute cholangitis, sepsis, bilirubin > 10-15 mg/dL, scheduled neoadjuvant therapy and the need for extensive hepatic resection are indications for preoperative biliary drainage.The goal is to reduce peri- and postoperative complications[23,24,26,29].Cholestasis, liver dysfunction and biliary cirrhosis can develop rapidly with unrelieved obstruction and may influence postoperative morbidity and mortality after surgery[23-26,33].The definitive operation is deferring until bilirubin levels are less than 2 to 3 mg/dL[33].

Some centers prefer preoperative biliary decompression in order to decrease the total bilirubin level to under 3 mg/dL, whereas others recommend resection in patients without biliary drainage.In our center the decision to perform preoperative biliary drainage is made in the setting of a multidisciplinary team, and it is not generally recommended unless severe liver dysfunction is suspected.

It should be taken into account that the stent may induce different artifacts in subsequent images.Therefore, previous high-quality imaging is required (computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic ultrasound and intraductal ultrasonography) to assess the tumor resectability[23-26,33].The biliary stent may be a hindrance for the surgeon to find the proximal tumor extent.Resection of pCCA always requires a concomitant major liver resection.Liver segments that will remain after surgery should be drained sufficiently with a plastic stent to improve postoperative liver function and regeneration[29].

There are different data regarding the benefits of preoperative biliary drainage in jaundice patients with pCCA without absolute indications for biliary drainage[29].The most recent studies concluded that routine biliary drainage does not impart any advantage because it does not improve the morbidity or mortality of patients with resected pCCA[31,34,35].A recent meta-analysis and a systematic review showed that preoperative biliary drainage have not changed the incidence of postoperative complications, hospitalization time, R0 or survival rate.However, in jaundice patients, preoperative biliary drainage decreased postoperative mortality[36].

In dCCA, a European multicenter study did not find any differences regarding mortality rate in patients with preoperative biliary drainage[37].Moreover, in a recent retrospective study, preoperative endoscopic biliary drainage was associated with a decrease in the survival rate[38].

In PTBD, some studies reported that catheter tract recurrence rates were up to 6%[32], and the median time of recurrence was months.Furthermore, the technical success rate regarding the decrease of biliary level is higher with the endoscopic approach than with PTBD[39,40].In a recent randomized prospective study, the risk of cholangitis in patients who underwent surgery was higher in the PTBD group compared with the endoscopic biliary drainage group (59%vs37%) (P= 0.1)[41].

PTBD is no longer recommended for preoperative biliary drainage in patients with extrahepatic CCA, and an endoscopic approach is currently preferred[24,26].The risk of endoscopic plastic stent occlusion is 60%.Therefore, there are several groups of experts who recommend preoperative nasobiliary drainage.Kawashimaet al[42]compared preoperative nasobiliary drainage with endobiliary stenting drainage in 164 patients with pCCA.They found a longer stent patency and a lower risk of cholangitis in the nasobiliary group than the endobiliary stenting group.

Palliative biliary drainage

The relief of symptoms (pain, pruritus, jaundice) and improvement in quality of life are the goals of palliative therapy.Radiotherapy, PDT, RFA, local ablation and embolization are nonsurgical local therapies that can prolong the time to local failure (in patients with macroscopically positive margins) or to palliate local symptoms, pain or jaundice (in patients with unresectable or recurrent disease).

In patients with pCCA and dCCA who are not suitable for surgery or liver transplantation, the guidelines recommend endoscopic bile duct drainage as the first approach[23,24,26,34].In patients with a good performance status an additional treatment, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, molecularly targeted therapy and/or immunotherapy, is recommended[25].

Stenting

Stent implantation by ERCP should be the standard procedure[24-26](Figure 4 and 5).Placement of a stent is generally preferred for long-term palliation.This approach has similar successful palliation and survival rates and less morbidity compared with the surgical approach[43].The endoscopic drainage with one or more stents is technically possible in 70% to 100% of cases.The extent of decompression that is necessary to restore sufficient bile flow while avoiding the risk of bacterial cholangitis, the optimal approach to placement of the stents and the use of plastic or metal uncovered/covered stents are the major issues of biliary endoscopic stenting[44].

The goal of palliative drainage is to drain more than one half of the biliary tree, although it has been shown that the jaundice may be clinically improved if only a quarter of the liver is drained[45].A target stenting using previous superior imaging methods is preferred[44].In cases of cholangitis, drainage of all suspected infected intrahepatic segmental branches should be performed[24].

In complex and difficult cases a multimodality biliary drainage (transpapillary drainage in combination with PTBD) should be considered[44].Rendezvous technique, anterograde PTBD and transluminal stenting through the stomach, duodenum or jejunum walls are the procedures using EUS-BD in these cases.This approach can be performed even when a passage of a wire through a biliary stricture is not possible[46].In a meta-analysis conducted by Lenget al[47], the technical success rate of PTBD varied from 60% to 90% and the morbidity rate from 18%to 67%.In some difficult cases, an external drainage has been required.Therefore, the quality of life of these patients is decreased.EUS-BD technical success varied from 70% to 100%, and the rate of complications was up to 77%[48,49].A few comparative studies are available[50-54](Table 1).The technical success rates are similar in most studies with a higher incidence of complications for PTBD than EUS-BD[50-54].

Unilateral or bilateral endoscopic stenting

In most cases, unilateral stent placement should be adequate for biliary drainageviaERCP because only 25% to 30% of the liver needs to be drained to relieve jaundice[54-56].However, unilateral drainage alone may not relieve jaundice completely and may increase the risk of cholangitis due to contrast medium injection into undrained bile ducts[45].Unilateral stenting is technically easier and less expensive than bilateral stenting with reintervention for stent dysfunction also being considerably easier[45].In our practice, we prefer to place a unilateral self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS) in order to provide good efficacy of biliary drainage with minimum risk of cholangitis.In clinical practice, many endoscopists prefer to place bilateral stents (plastic or metal) in an attempt to maximize biliary drainage and to prevent cholangitis.

Table 1 Success rate and complications for percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage, endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and self-expandable metal stent

Figure 4 Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Previous studies have demonstrated that bilateral stenting is associated with longer stent patency compared to unilateral stenting[57,58].In a recent multicenter prospective randomized study conducted by Leeet al[59], the same survival rate in patients with bilateral SEMS biliary drainage but with a longer stent patencyvsunilateral SEMS biliary stenting were shown.No significant difference between unilateral and bilateral SEMS regarding the technical success or complications was shown[59].These results highlighted the superiority of bilateral stenting.However, several study results have similarly supported the superiority of unilateral stenting[54-56,60].

In a recent meta-analysis involving 782 patients, bilateral biliary drainage had a lower re-intervention rate compared to unilateral drainage in patients with pCCA with no significant difference in technical success and early or late complication rates[61].

Plastic stents or SEMS

Figure 5 Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Endoscopic biliary drainage can be performed using plastic or SEMS.There are a variety of plastic and metal stents, covered or uncovered.While some studies showed benefits of metallic stents regarding the successful drainage and early complication rate, stent patency and survival rate[55-59,62], a systematic review concluded that neither stent type offered a survival advantage[63].The decision to use onevsanother should be guided by the expected length of survival, quality of life, costs and physician expertise.Usually, SEMS should be considered for patients with a life expectancy of longer than 3 mo[44].The results of different meta-analyses that compared SEMS with plastic stents for endoscopic drainage of distal malignant biliary obstruction are illustrated in Table 2[62-66].

Plastic (polyethylene) stents are inexpensive, effective and easily removable or exchangeable[38-44].The major disadvantage is a higher rate of occlusion by sludge and/or bacterial biofilm with cholangitis development and necessity of multiple ERCPs[60,62-66].Instead, metal stents have a longer patency (approximately 8-12 movs2-5 mo for plastic stents)[61-66], higher costs and may not be removable.The high occlusion rate of plastic stents (average 42%) can be reduced by changing the stents every 3-6 mo[60,62-66].Another way is to wait for a complication before changing the stent because many patients will die before the stents will obstruct.The preferred approach for patients who are expected to live beyond a few months is to replace the plastic stent with a metal one as soon as is feasible[44].

In dCCA, uncovered SEMS are used in patients with an intact gallbladder[26].For patients who have undergone prior cholecystectomy, the choice of a coveredvsuncovered SEMS is individualized given the location and geometry of the stenosis.Patients with extrinsic compression may be adequately treated with an uncovered SEMS, while those with intrinsic and/or papillary tumors may benefit from a covered SEMS in an attempt to minimize tumor ingrowth[26,67,68].The patency rates are not higher for covered stents despite showing significantly less tumor ingrowth.Tumor overgrowth and stent obstruction by debris and biliary sludge are associated with a low patency rate for uncovered SEMS[68].Covered SEMS should be used for pCCA.Deployment may inadvertently result in the occlusion of a major hepatic duct[24,26,44,68].

The stent in stent technique (Y stenting) and the side-by-side technique (Figure 6) are two endoscopic techniques for biliary drainage in CCA.By using the Y stent technique, Hwanget al[69]demonstrated an 86.7% technical success rate and a 100% functional success rate regardless of the stent type.For side-by-side stenting technique in pCCA, Leeet al[70]reported a 91% technical success rate and a 100% functional success rate with no statistically significant difference between stent patency and median survival of the 8-mm and 10-mm groups.

The reported rate of stent dysfunction following pCCA biliary drainage was 45%-57% due to tumor ingrowth, tumor overgrowth or stent migration[55-58].Given the fact that SEMS may be successfully revised in the majority of cases and that the second SEMS have a higher patency compared with plastic stents, it seems that SEMS are the best choice in cases of SEMS dysfunction[55-59].

Guidelines recommend prophylactic antibiotics in patients with plastic or metal stents for long-term palliation of obstructive jaundice after the first episode of cholangitis[24,26,44].In 5%-10% of cases, endoscopic biliary drainage by ERCP will fail or will be incomplete[54-69].In this case, multimodality drainage should be considered[24,26,44].

Percutaneous vs endoscopic approach

Several studies have shown a higher rate of successful palliation of jaundice and lower rates of cholangitis in the percutaneous approach rather than the endoscopic approach of biliary drainage in patients with malignant hilar obstruction (pCCA/gallbladder cancer)[71-73].Bile leaks and bleeding are more frequent and morbidity and mortality are higher than the endoscopic approach[73].Percutaneous stents are usually left to open drainage externally from the body and are less comfortable for the patient.Another technique is the combination of ERCP with percutaneous drainage.

Table 2 Meta-analyses comparing self-expandable metal stents with plastic stents for the endoscopic drainage of distal malignant biliary obstruction

Figure 6 Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

EUS-BD:EUS-BD has been proposed as an effective alternative for PTBD after failed ERCP[74-80].The use of EUS-BD is feasible for a left system drainage procedure in patients with advanced CCA who failed transpapillary drainage[74-80].For extrahepatic CCA, the procedure of choice is EUS-guided hepatico-gastrostomy, which allows left system access only.It is less invasive given that it affords a more accurate control as well as more access sites to the bile duct than the classical alternatives of PTBD or surgery[77].After the identification of the biliary duct, the technique consists of puncturing and dilatation by EUS with stent placement across the bile duct into the digestive lumen.Literature data showed a 94.0% per-protocol success rate and a 90.2% intention-to-treat basis success rate[75-81].

Peritoneal bile leakage and cholangitis are the most frequent complications[75-81].Early migration or the clogging of the plastic stents may lead to cholangitis[76].Bile peritonitis and biloma are more frequent in transmural SEMS placement[77,80].However, most complications are mild and can be conservatively treated[81].By combining an uncovered metal stent with a covered metal stent inside, the risk of leakage is minimized.The uncovered stent is initially deployed to provide anchorage and prevent migration.The covered stent is inserted coaxially and dropped in the first stent.A fully covered SEMS[77]or a double pig-tail stent through the expanded SEMS may be used to prevent stent migration[78].

The advantages of EUS-guided hepatico-gastrostomy over rendezvous or anterograde stent insertion are particularly relevant in patients with prior duodenal or biliary SEMS who experience recurrent biliary obstruction[79,81].Dhiret al[82]compared ERCP-guided biliary drainage with EUS-guided approach in patients with malignant distal obstruction who required SEMS placement.They found that the short-term outcome of EUS-BD is comparable to that of ERCP.Postprocedural pancreatitis rates were higher in the ERCP group[82,83].Clinical efficacy of a novel technique of EUS-BD for right intrahepatic bile duct obstruction was evaluated[84,85].Most of the studies have only shown the role of EUS-BD in distal biliary obstruction, and the utility of EUS-BD for pCCA is limited.Recent studies have reported the efficacy of EUS-BD in a setting of failed ERCP for biliary drainage in proximal malignant obstruction[86,87].

Kongkamet al[88]proposed a new concept of a combination of ERCP and EUS-BD for biliary drainage in pCCA as a primary biliary drainage method whereby ERCP with a single SEMS is placed into either the right or the left intrahepatic bile duct.In cases of failure of all interventional options, surgical bypass should be considered as the last rescue procedure.It is typically only performed during an unsuccessful attempt at resection, or it may be necessary in jaundice patients in whom stenting is not possible due to tumor location[1,6,7,18].

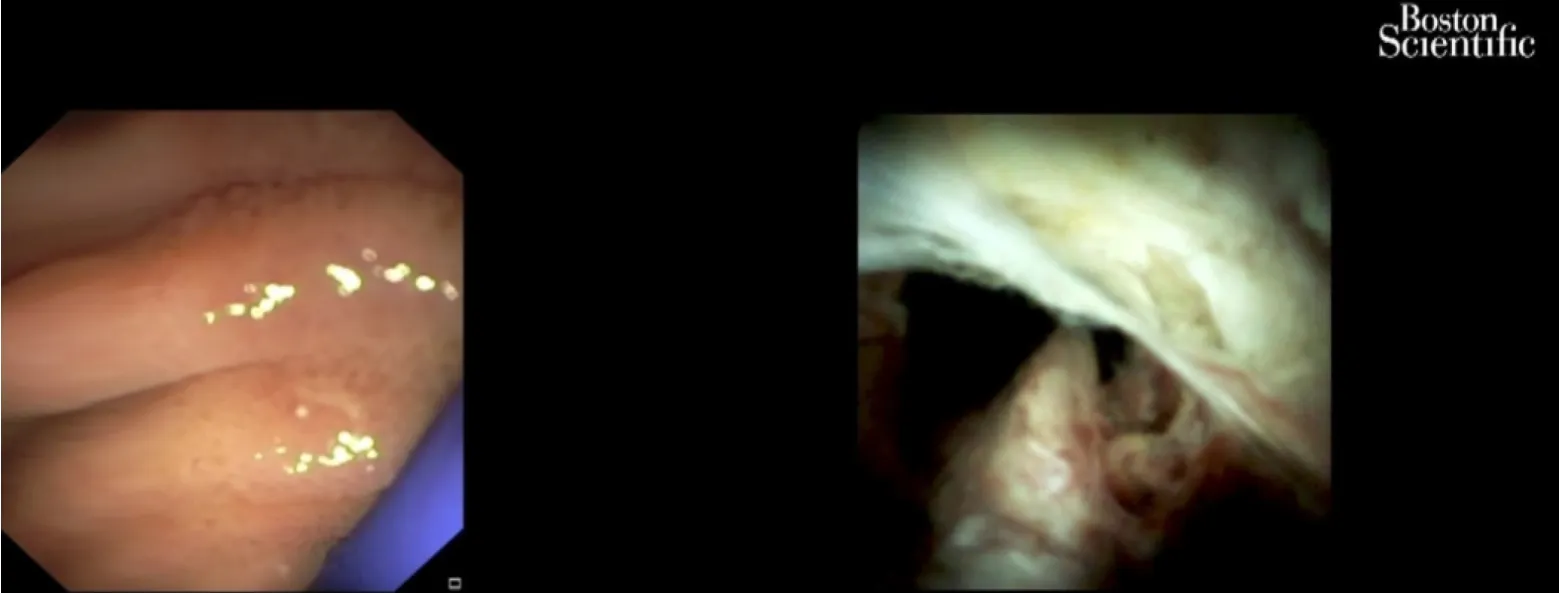

ROLE OF CHOLANGIOSCOPY

Peroral cholangioscopy (POC) allowing direct visualization of the biliary tract with targeted biopsy of suspicious lesions is a useful diagnostic procedure in the evaluation of biliary strictures (Figure 7).A recent study[89]showed that POC use for the assessment of intraductal spread in potentially resectable pCCA can accurately detect and can change surgical management.In the future, preoperative staging of CCAs should combine radiological with endoscopic (i.e.POC evaluation) in order to optimize surgical results.

Another study[90]compared the performance characteristics of single-operator cholangioscopy-guided biopsies and transpapillary biopsies with standard sampling techniques for the detection of CCA.It showed that single-operator cholangioscopyguided and transpapillary biopsies improved sensitivity for the detection of CCAs in combination with other ERCP-based techniques compared to brush cytology alone.However, it seemed that these modalities did not significantly improve the sensitivity for the detection of malignancy in primary sclerosing cholangitis.

A very recent publication[91]evaluated a newly developed POC classification system by comparing classified lesions with histological and genetic findings.Thirty biopsies were analyzed from 11 patients with biliary tract cancer who underwent POC.An original classification of POC findings was made based on the biliary surface’s form (F factor, 4 grades) and vessel structure (V factor, 3 grades).Histological malignancy rate increased with increasing F- and V-factor scores.The system was validated by comparing it to the histological diagnosis and genetic mutation analysis in simultaneously biopsied specimens.F-V classification is the first reported system to quantify and classify biliary tract cancer based on POC findings.

RADIOFREQUENCY ABLATION

Percutaneous image-guided RFA is a potential “new tool” for the endobiliary treatment of pCCA[92].After selective intrahepatic duct cannulation, the 0.035-inch guidewire is placed across the stricture point.The lesion is identified during cholangiography.After the previous sphincterotomy, the RFA is performed using a specific catheter.It is mandatory for all of tumor area to be caught during the procedure.The coagulated tissue will be removed using a balloon probe, and a stent will be inserted[93].There are only a few studies regarding the successful therapy with intraductal RFA for pCCA[94,95].A recent study[95]including 65 patients with unresectable extrahepatic CCA showed that the mean survival time was significantly greater among those who underwent RFA plus stenting compared with stenting alone (13 movs8 mo).At 12 mo, the survival rate was 63% in the RFA group compared with 12% in the stenting-only group.Stent patency was also longer in the RFA group (7 movs3 mo).The adverse event rate did not differ significantly between groups (6% and 9%).

Figure 7 Cholangioscopy: Hilum malignant obstruction.

These results are overlapping with those of a meta-analysis, which was comprised of 505 patients and evaluated the effectiveness of biliary stent placement with RFA on stent patency and patient survival[27].The pooled weighted mean difference in stent patency was 50.6 d, favoring patients receiving RFA and an improved survival in patients treated with RFA.RFA was associated with a higher risk of postprocedural abdominal pain.There was no significant difference between the RFA and stent placement-only groups with regard to the risk of cholangitis, acute cholecystitis, pancreatitis and hemobilia[27].

A prospective open-label multicenter study included 12 patients with histologically proven endobiliary adenoma remnant (ductal extent < 20 mm) after endoscopic papillectomy for ampullary tumor.RFA was performed during ERCP with biliary ± pancreatic stent placed at the end of the procedure.All underwent one successful intraductal RFA session with biliary stent placement and recovered uneventfully.Five (25%) received a pancreatic stent.The rates of residual neoplasia were 15% and 30% at 6 and 12 mo, respectively.Only two patients (10%) were referred for surgery.Eight patients (40%) experienced at least one adverse event between intraductal RFA and 12 mo of follow-up.No major adverse events occurred.Intraductal RFA of residual endobiliary dysplasia after endoscopic papillectomy can be offered as an alternative to surgery with a 70% chance of dysplasia eradication at 12 mo after a single session and a good safety profile[96].

PHOTODYNAMIC THERAPY

PDT is the use of photosensitizing agents that accumulate into the tumor.The agents are activated by laser light.Free oxygen radicals are released and destroy the neoplastic cells[69].Apoptotic death of cells is another mechanism produced by PDT with an immunomodulatory effect.Hematoporphyrin derivatives, ∂-aminolevulinic acid and meso-tetra (hydroxyphenyl) chlorin are the photosensitizing agents used for CCA treatment[24,97].Strong phototoxic skin reactions that can persist for weeks are a disadvantage of the use of photosensitive substances such as photofrin (porfimer sodium).The advantage of the ∂-aminolevulinic acid, which is a second generation photosensitizer, is the lack of prolonged photosensitization and laser light exposure.

The endoscopic PDT technique involves intravenous 48-h administration of the photosensitizing agent prior to the laser light illumination.The specific substance is retained in tumor cells and into the skin longer than 48-72 h like in the normal tissues.With a guidewire and a catheter, the light laser fiber is placed across the tumoral stricture (Figure 8).The power density used is 300-400 mW/cm with a power energy of 180-200 J/cm.The irradiation time is 400-600 s[97].Due to the fact that light laser fiber is stiff, the breakage may occur in up to one third of the procedures, making the procedure a bit more cumbersome and affecting treatment cost[24,44].The PDT is only performed in some specialized centers.

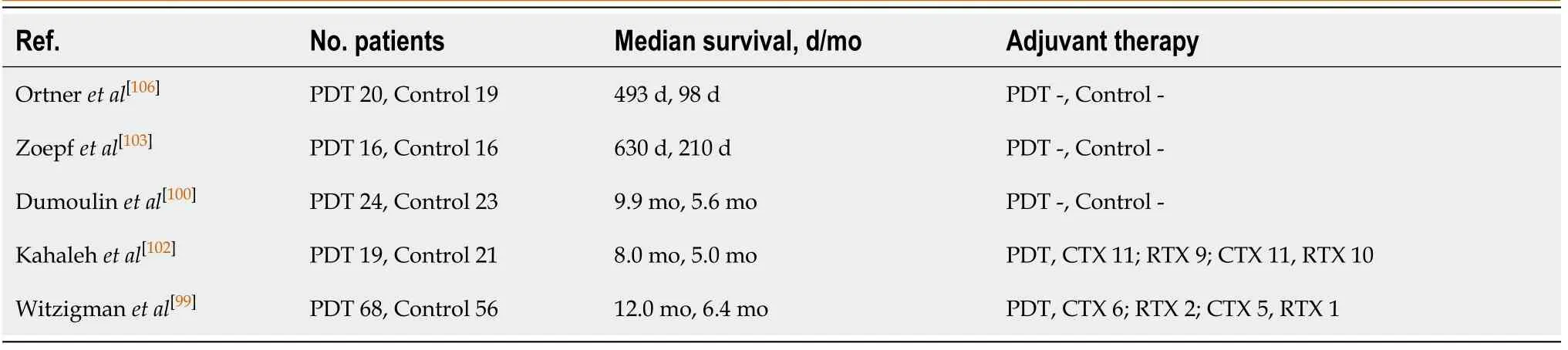

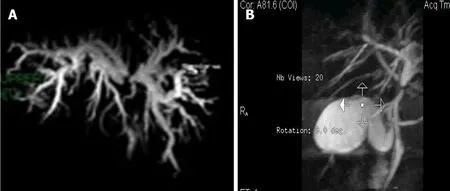

In addition to facilitating biliary decompression after stenting in patients with locally advanced disease, survival might be improved in patients who undergo PDT[98-107](Figure 9).The data showed a survival benefit for this approach with favorable early results including longer survival and quality of life[98,105,106](Table 3).The survival benefit was related to the prolonged relief of obstruction rather than to a reduction of the tumor.Although the factors that are associated with prolonged survival are not completely known, at least some data suggest that the absence of a visible mass on radiographic studies correlates with longer survival after PDT[44,107].

Table 3 Photodynamic therapy in patients with cholangiocarcinoma

Figure 8 Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Figure 9 CholangioIRM.

Cholangitis and a liver abscess are the main complications of photodynamic therapy[98-107].Data suggest that combining photodynamic therapy with systemic combination chemotherapy improved outcomes over PDT alone for patients with nonresectable tumors without increasing toxicity rates, although randomized trials have not been conducted[108-112].At the moment, PDT is being studied preoperatively as a means of improving the likelihood of achieving a margin-negative resection[113].

In a recent meta-analysis conduct by Luet al[114], overall survival was significantly better in patients who received photodynamic therapy than those who did not.Among the eight trials (642 subjects), five assessed the changes of serum bilirubin levels and/or Karnofsky performance status as other indications for improvement.The incidence of phototoxic reaction was 11.11%.The incidence for other events in photodynamic therapy and the stent-only group was 13.64% and 12.79%, respectively.

A new model of a photosensitizer-embedded self-expanding metal stent (PDT-stent) that provides a photodynamic effect without a systemic injection has been developed.The treatment could be repeated due to the incorporation of the polymeric photosensitizer into the mesh of the stent.The stent maintained its photodynamic power for at least 8 wk.This type of stent after light exposure creates cytotoxic free radical, such as singlet oxygen, in the surrounding tissue and induces destruction of tumoral cells on animal models[115].Unfortunately, PDT is not widely available and is expensive and uncomfortable for the patient.

BRACHYTHERAPY

The purpose of brachytherapy (BT) is to deliver a high local dose of radiation to the tumoral tissue while sparing healthy tissue around it.It can be adapted for right and left hepatic duct and for common bile duct lesions.It plays a limited but specific role in the curative intent treatment in selected cases of early disease as well as in postoperative small residual tumoral tissue.The indications for BT are as radical or palliative treatment.For radical treatment, it is recommended in small inoperable tumors or in combination with external beam radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy in advanced disease for unresectable tumors.BT may be used as adjuvant treatment after nonradical excision, possibly combined with external beam radiation therapy.The most common indication for BT occurs as palliative in unresectable Klatskin tumors.The purpose is to prevent locoregional disease progression and to facilitate the bile outflow.The major aim is to improve the quality of life and to increase survival.The treatment decision should be personalized[116].

ERCP-directed tumor therapy using iridium-192 ribbonsvianasobiliary catheters in patients with pCCA as part of a neo-adjuvant treatment protocol that include external beam radiation therapy, radiation-sensitizing chemotherapy and low-dose-rate BT (< 3000 cGy) followed by liver transplant was first described in 2006[117].High-dose-rate (HDR)-BT using 930-1600 cGy fractionated in 1-4 doses over 1-2 d was introduced in 2009[117].The benefits of this technique are lack of irradiation of medical staff, lower time span (5-10 min), a better distribution of doses in the tumor and protection of the stomach and duodenum[117].Using ERCP, an 8.5 Fr or 10 Fr nasobiliary tube is placed into the biliary system with the proximal end of tube at least 2 cm beyond the proximal end of the tumor.In cases of bilateral duct involvement, a second 10 Fr tube is placed.After HDR-BT is completed, the tubes and brachycatheter are removed.Nasobiliary BT catheter displacement, cholangitis, abdominal pain, duodenopathy and gastropathy are possible complications[118,119].

Some studies demonstrated longer survival in patients with CCA due to the BT.Extrahepatic localization of CCA, the absence of metastases, increasing calendar year of treatment and liver transplantation with postoperative radiation therapy were factors significantly associated with improved survival[118,119].However, another study did not find any benefit regarding the survival in patients treated with PTBD-guided iridium-192, intraluminal BT compared with patients with only PTBD[120].These results are in accordance with another study that found a correlation only with local tumor control[121].

In a recent study[122], 122 patients with CCA were successfully treated with HDR-BT using the nasobiliary technique.The BT was not completed in three patients because either the catheter migrated between the ERCP and the treatment (two patients) or the HDR after loader was physically unable to extend the source wire into the treatment site (one patient).These three patients benefited from an external beam boost instead of HDR-BT.Intraluminal HDR-BT with a nasobiliary catheter is a minimally invasive method for administering neoadjuvant radiotherapy.

PALLIATIVE AND ADJUVANT CHEMOTHERAPY

The assessment of patients with CCA before starting chemotherapy includes the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group patient scale used for the evaluation of the patient performance status, disease distribution and accessibility of tumor profiling[123].The current data support the use of first-line cisplatin and gemcitabine combination regimen chemotherapy.The multicenter phase III ABC-02 study illustrated the superiority of the combination regimen regarding median overall survival (11.7 mo) over the gemcitabine monotherapy (8.1 mo)[124,125].

New combinations and more intensive triple chemotherapy are being explored.The combinations include: Cisplatin-gemcitabine combined with nab (nanoparticle albumin-bound)-paclitaxel[126]; S1 (tegafur, gimeracil and oteracil)[127]; and FOLFIRINOX ( 5-FU, oxaliplatin and irinotecan; AMEBICA study , NCT02591030).Acelarin is a nucleotide-analogue independent of hENT2 (also known as SLC29A2) cellular transport and is not metabolized by cytidine deaminase, resulting in greater intracellular concentrations.Cisplatin with acelarin was compared with the classic combination regimen of cisplatin and gemcitabine in a phase III study[128].

A recent phase III clinical trial ABC-06[129]randomly assigned 162 patients with advanced biliary cancer (72% with CCA) who obtained symptom control from firstline cisplatin-gemcitabine (81 patients) or second-line chemotherapy with FOLFOX (folinic acid, 5-FU and oxaliplatin) (81 patients).The results showed a benefit from second-line chemotherapy regarding survival at 6 mo (35.5%vs50.6%) and 12 mo (11.4%vs25.9%), but no significant differences regarding overall survival (5.3 movs6.2 mo) were observed.

A very difficult to handle and a major issue in the management of patients with CCA is the poor response to pharmacological treatment.A cause could be the poor understanding of the mechanisms of chemoresistance.To identify the so-called “resistome” that includes a set of proteins involved in the lack of response to chemotherapies is required to increase efficacy.Genes involved in mechanisms of chemoresistance are usually expressed by normal cholangiocytes because one of their roles is the protection against potentially harmful compounds present in bile.Their expression during carcinogenesis contributes to intrinsic chemoresistance, and upregulation in response to treatment leads to acquired chemoresistance[130-132].

MOLECULAR TARGETED THERAPY

Recent molecular studies have increased the understanding of the pathogenetic mechanism of CCAs, but to date the clinical data on immune-directed therapies in CCA are limited.

Inhibitors of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) 1, IDH2 and pan-IDH1-IDH2 are currently being tested in patients with intrahepatic CCA.Ivosidenib (IDH1 inhibitor) was tested in 73 patients with IDH1-mutant advanced CCA in a phase I study with no major adverse events reported[133].A recent preliminary phase III trial showed a benefit for ivosidenib over placebo in terms of progression free-survival.One hundred eightyfive patients with IDH1 mutant CCA were randomly assigned to ivosidenib or placebo.This study highlighted the importance of molecular profiling in CCA[134].

There are some phase II studies with encouraging preliminary data for fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitors in patients with CCA.Some fibroblast growth factor receptors inhibitors are currently being evaluated as first-line treatment, for example the FIGHT-302 study (NCT03656536) and the PROOF study (NCT03773302)[135-137].

CONCLUSION

CCAs are heterogeneous and highly aggressive tumors with a poor prognosis despite the progress of the research in this field.Surgical resection is still the only potential curative treatment method.The recent findings on understanding the mechanism of chemoresistance and molecular targeted therapy could bring a new horizon in the approach of these tumors.Currently, endoscopic treatment in patients with CCA and jaundice remain the first choice of biliary duct decompression, either preoperatively or with a palliative purpose.The combination of endoscopic procedures with nonsurgical local methods or additional therapies may increase the quality of life and the rate of survival in patients with locally advanced, unresectable or recurrent disease.

杂志排行

World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Meeting report of the editorial board meeting for World Journal of Hepatology 2021

- Adult human liver slice cultures: Modelling of liver fibrosis and evaluation of new anti-fibrotic drugs

- Production and activity of matrix metalloproteinases during liver fibrosis progression of chronic hepatitis C patients

- Awareness of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and treatment guidelines: What are physicians telling us?

- Occult hepatitis C virus infection in the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Two-stage hepatectomy with radioembolization for bilateral colorectal liver metastases: A case report