Status and path of intergenerational transmission of poverty in rural China:A human capital investment perspective

2021-03-23BAIYunliZHANGLinxiuSUNMingxingXUXiangbo

BAI Yun-li ,ZHANG Lin-xiu, SUN Ming-xing ,XU Xiang-bo

1 Key Laboratory of Ecosystem Network Observation and Modeling,Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research,Chinese Academy of Sciences,Beijing 100101,P.R.China 2 UN Environment Programme-International Ecosystem Management Partnership,Beijing 100101,P.R.China

Abstract This paper focused on the intergenerational transmission of poverty in rural China by estimating the intergenerational transmission of earnings and stated its mechanism from the perspective of human capital investment before children participated in the labor market. The data used in this study were longitude data collected in 2 000 households of 100 villages among 25 counties across five provinces in 2005,2008,2012,2016,and 2019. Qualitative and quantitative methods were adopted. We found a significant intergenerational transmission of earnings in rural China,especially for the pairs of father–children and parents–children. The intergenerational earnings’ elasticities were much less than those in urban areas,which indicated better social mobility in rural areas than that in urban China. The children with parents who could earn much were more likely to be invested before they participated in the labor market,gain a high education and have more skills. Three cases further showed that the mechanism of human capital investment in children breaking the intergenerational transmission of poverty and promoting social mobility.

Keywords:poverty,intergenerational transmission,human capital,rural China

1.Introduction

Poverty is the first global challenge under the sustainable development goals set by the United Nations (2015).According to the most recent estimates,10% of the world’s population lived on less than US$1.90 a day in 2015 (World Bank 2018),and most of them lived in developing countries.Worldwide,the poverty rate in rural areas is 17.2% -more than three times higher than that in urban areas (United Nations 2020).

The biggest challenge for poverty alleviation is to break the intergenerational transmission of poverty (ITP),especially in developing countries. The ability to move up the income ladder is a matter of fairness and has major implications for poverty reduction (Breen and Jonsson 2005;Kambourov and Manovskii 2009; Warzywoda-Kruszyńska 2013; Chettyet al.2014; Narayan 2018). Most of the literature has focused on the ITP in the developed countries,such as the United States,Canada,the United Kingdom,and Spain (Rodgers 1995; Deardenet al.1997; Blanden and Gibbons 2006; Cardaket al.2013; Duarteet al.2018).However,the studies on the ITP in developing countries were rare and only recently appeared (Kabeer and Mahmud 2009; Cooper 2010; Gonget al.2012; Denget al.2013; Fan 2016; Behrmanet al.2017; Wuet al.2019). Notably,both absolute and relative social mobility is lower in low-and middle-income countries compared with that in high-income countries,according to the report from the Global Database on Intergenerational Mobility (Narayanet al.2018).

Most of the literature on ITP has focused on the intergenerational transmission of family income or individual earnings (Atkinsonet al.1983; Solon 1992,1999; Chadwick and Solon 2002; Pascual 2009; Cardaket al.2013; Fan 2016; Qinet al.2016). However,a few studies have used the possibility of being poor (Rodgers 1995; Quisumbing 2008). The previous studies measured the intergenerational elasticity in income or earnings by specifying a linear regression equation between log income or earnings of children and log income or earnings of parents. The significance and magnitude of intergenerational elasticity in income or earnings depended on the definition of the outcome variable and the different estimation methods in the literature.

There are multiple definitions of family income and individual earnings. Fan (2016) defined family income as the total annual average income of the father and mother in at least three preceding years of the survey wave. Qinet al.(2016) took the average values of fathers’ annual income in all sample waves as a proxy measure of fathers’permanent income and yearly income as a measurement of son’s income. The definition of individual earnings was more consistent than that of family income. It referred to wages,bonuses,and other subsidies provided by the employer.However,the measurement of earnings varied among these studies. Log of hourly earnings,log of weekly earnings,log of monthly earnings,and annual earnings were usually used to measure the son’s and father’s earnings (Atkinsonet al.1983; Hertz 2001; Cardaket al.2013). Some studies have used the log of average earnings over several years of children and parents to alleviate potential biases induced by income fluctuations and lifecycle effects (Osterbacka 2001; Mazumder 2005; Lee and Solon 2006; Nicoletti and Ermisch 2008; Gonget al.2012). For reviews,see Solon(2002) and Black and Devereux (2011).

Ordinary least squares (OLS) and instrumental variable(IV) were usually used to estimate the intergenerational transmission of income or earnings in the literature. OLS was the earliest and most widely used method (Solon 1992; Hertz 2001; Osterberg 2001; Denget al.2013). For example,Denget al.(2013) used a one-year and average of three years of children’s incomes as independent variables and corresponding income of parents as the key regressor to estimate the intergenerational income elasticity with the samples of urban households in China in 1999 and 2002 by adopting the OLS estimation method. The IV estimation method has been adopted in some related studies. The common IV used in the literature was predicted earnings in parents’ occupations (Leigh 2007). The two-sample instrumental variables approach was another common method that has been used to estimate ITP (Nicoletti and Ermisch 2008; Gonget al.2012; Lefrancet al.2014).

When estimating the intergenerational transmission of income or earnings,some characteristics affecting children’s income or earnings are included in the model. Gender has been proved to be an important trait influencing off-farm wage (Wanget al.2016,2019). The education,skill,and physical health status were often included in the model to control the impact of human capital on the off-farm wage(Kamgaet al.2013; Heckmanet al.2014; Wanget al.2016,2019). The experience usually measured by age was also controlled in these studies. Previous studies found wage premium among different cities (Yankow 2006; Zhouet al.2018).

Researchers have found that human capital,including education,health,and nutrition,was widely recognized as a key mechanism for escaping from ITP (Glewweet al.1999;Harperet al.2003; Quisumbing 2008; Bird and Higggins 2011; Room 2011; Gonget al.2012; Qinet al.2016; de Vuijstet al.2017; Duarteet al.2018). Education,a critical indicator of human capital,has been widely mentioned for its contribution to social mobility (Ruiz 2016). Poor health was the central issue faced by poor groups (Mackintosh 2001;Freedman 2005). Bad health could be both an outcome and a cause of poverty. Poverty created the situation in which bad health was occurred and perpetuated,such as low productivity and income,inadequate diets,unsafe working and living environments,and reduction in long-term investment (Grant 2005). But bad health also led to poverty through reducing income of adults when with increasing expenditures on health care and through the long-term irreversible effects on functional capabilities,including ability to maximize returns on the acquisition of education(Mayer-Foulkes 2003).

The key precondition for breaking the ITP is to clarify the mechanism of ITP. The empirical studies on this topic have been rare because of the limitation of long panel data. To our knowledge,only several studies have investigated this topic in China. Gonget al.(2012) estimated the intergenerational income elasticity for urban China by using the Urban Household Education and Employment Survey 2004 and the Urban Household Income and Expenditure Survey 1986–2004. Denget al.(2013) estimated the intergenerational income elasticities by using samples of urban China for the years 1999 and 2002. Fan (2016) investigated the intergenerational income association and its transmission channels amid China’s economic transition period by using urban data from the Chinese Household Income Projects in 1995 and 2002. Qinet al.(2016) studied the impact of human capital transmission across generations on the intergenerational income mobility in urban and rural areas of China using 1989–2009 China Health and Nutrition Survey data. Wuet al.(2019) analyzed the regional differentiation characteristics of ITP and explored its impact mechanisms based on a sustainable livelihood framework. Among these studies,only Qinet al.(2016) used the sample including rural households.

The ITP in China,the biggest developing and most populous country in the world,has been paid an increasing attention from scholars and policymakers. The Chinese central government is determined to eradicate absolute poverty by 2020,in which preventing ITP was one of the most important challenges (State Council 2015). The new terms “Fu-er-dai” (children of rich families),“Guan-erdai” (children of government officials),and “Nong-er-dai”(children of peasants) reflect the persistent influence of parents’ socioeconomic positions on their children. Some scholars have estimated intergenerational transmission elasticity from the perspective of income,education,occupation,and self-employment business (Fan 2016; Qinet al.2016; Donget al.2019; Wang W Det al.2020; Zhuoet al.2020).

Despite the increasing attention on ITP in China,rigorous study of this topic has been scarce in rural areas. Rural areas hold 40.4% of the permanent residents in China and are the main targeted areas for poverty reduction because of the long-term existence of the urban–rural dual structure.China is a critical case study for understanding the nature of social mobility during the transition from a socialist command economy to a more market-oriented economy (Emran and Sun 2011). Therefore,focusing on breaking the ITP in rural China is important to narrow the socioeconomic gap between urban and rural areas in China and contributes to other developing countries.

This study attempts to estimate the ITP in rural China and identify its mechanism from the perspective of human capital investment in the offspring before they participated the labor market by adopting qualitative and quantitative methods. It contributes to the literature from three perspectives. First,identifying the mechanism based on the human capital investment before the offspring participate in the labor market using unique dataset. This study applies systematic logic of human capital investment in schooling affecting the capacity of earning wages after participating in the labor market. Second,it provides additional empirical evidence on human capital influencing intergenerational mobility in rural areas of developing countries. Third,it considers skills as a critical type of human capital when finding the mechanism of ITP,which is vital for the income of rural residents but has been neglected in the literature.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:Section 2 introduces data and methods of this study.Section 3 presents the results and discussion. Section 4 shows the mechanism of ITP. The conclusion is in Section 5.

2.Data and methods

2.1.Sampling and data collection

This paper used the panel data,namely,the China Rural Development Survey,collected by the authors. A multiround survey was administered to 2 000 households and village leaders of 100 villages in 25 counties across five provinces in 2005,2008,2012,2016,and 2019. The dataset was used widely to research the evolution of rural labor market,the intergenerational transmission of education and occupation,and the governance in rural China (Wonget al.2017; Zhanget al.2018; Donget al.2019,2020; Liuet al.2019; Wang H Jet al.2020; Wang W Det al.2020; Zhuoet al.2020). In the first round of the survey in 2005,each sample province was randomly selected from China’s major agroecological zones. Finally,Jiangsu,Sichuan,Shaanxi,Jilin,and Hebei provinces were selected.

Five sample counties were then selected from each province in a two-step procedure. First,the enumeration team listed all the counties in each province in descending order of per capita gross value of industrial output,which is a good predictor of the standard of living and development potential and often more reliable than the net per capita income (Huang and Rozelle 1996). Second,five counties per province were randomly selected from the resulting list.

From each selected county,the team selected sample townships and villages. Two townships were selected from each county,comprising one from each of the two groups per county:a “more well-off” group and a “poorer” group.Following the same procedure,two villages per township were selected. Finally,the survey teams randomly selected 20 households from each village:eight participated in the questionnaire survey and 12 participated in the small group interview. We also conducted four rounds of follow-up surveys in 2008,2012,2016,and 2019. All of the households in following surveys participated in the questionnaire survey.

The survey team gathered detailed information on individual demographics and household characteristics in each wave of the survey. Individual demographic characteristics included gender,birth year,years of schooling or the present grade,the number of siblings,and birth order. The human capital of the individual comprised the skill status,such as the type of skills,the start and final year of training for that skill,and physical health except for formal schooling. The team also documented each laborer’s employment status in the household,including whether they had off-farm work; the months in a year,days in a month,and hours in a day they worked off-farm; and the location and occupation of the off-farm employment. More importantly,we gathered information on the investment in an academic year in schooling for the children in each wave of survey,including tuition fees,incidental fees,book fees,course fees,and other fees related to schooling.1Amount of investment in formal schooling was not collected in 2012.

This dataset helped us construct the earning pairs of parents and their children,which we used to analyze the ITP,since the off-farm employment has been a major source of income for households in rural China (NBSC 2019; Luoet al.2020). We investigated the mechanism of ITP from the perspective of human capital investment,according to the information on years of schooling,skill training,physical health,and the investment in schooling.

We mainly used the data collected in 2019 to conduct quantitative analysis in this study. The sample in this study was limited to the rural laborers engaged in off-farm employment and his/her children who had performed offfarm work in 2018 and had finished their education. Finally,we obtained a sample of 322 pairs of fathers and their children,160 pairs of mothers and their children,and 102 pairs of parents and their children. Among these children,34,60,and 16 of them were in school when we surveyed in 2016,2008,and 2005,respectively. The data supported our analysis of the relationship between human capital investment and ITP. We also conducted case studies with 16 of the pairs to discuss the mechanism systematically because they had just started primary school in 2005 and have participated in off-farm employment since 2018. In other words,we used the data from 2005 to 2019 to do mechanism analysis and case study with the information on investment in education of the children before their participation in labor market.

2.2.ldentification strategy

Most economic analyses on the elasticity of intergenerational transmission of earnings or income have used the coefficient in the following intergenerational regression model.Additionally,using Holmlundet al.(2011) and Pronzato(2012),who have studied the intergenerational transmission of education,as references,we employed three empirical specifications to examine the intergenerational transmission of earnings from the father,mother,and parental average to the child. For each childiin householdh,we have:

For convenience,we definedEarningas the hourly earnings of an individual child.Earningdad,Earningmom,andEarningavgrepresented the hourly earnings of the father,mother,and the average of the parents,respectively. Hourly earnings has often been used to reflect the ability to earn in the labor market. In this study,we calculated hourly earnings by the total annual wages divided by the annual number of hours of off-farm employment.

Fwas a vector of other factors that may influence the child’s hourly wage. These factors are years of schooling,gender (1=male),age (years),number of vocational qualification certificates,experience in the current industry(months),job location (1=within the county),self-reported physical health (1=health),and a set of provincial dummies to capture regional factors that might affect the child’s wage.The description of the variables is presented in Table 1.εis the error term. Compared with models (1) and (2),model(3) had the advantage that it controlled assortative mating,avoided multicollinearity,and produced a more precisely estimated coefficient.

3.Results and discussion

3.1.Descriptive statistics of children and their parent’s wage

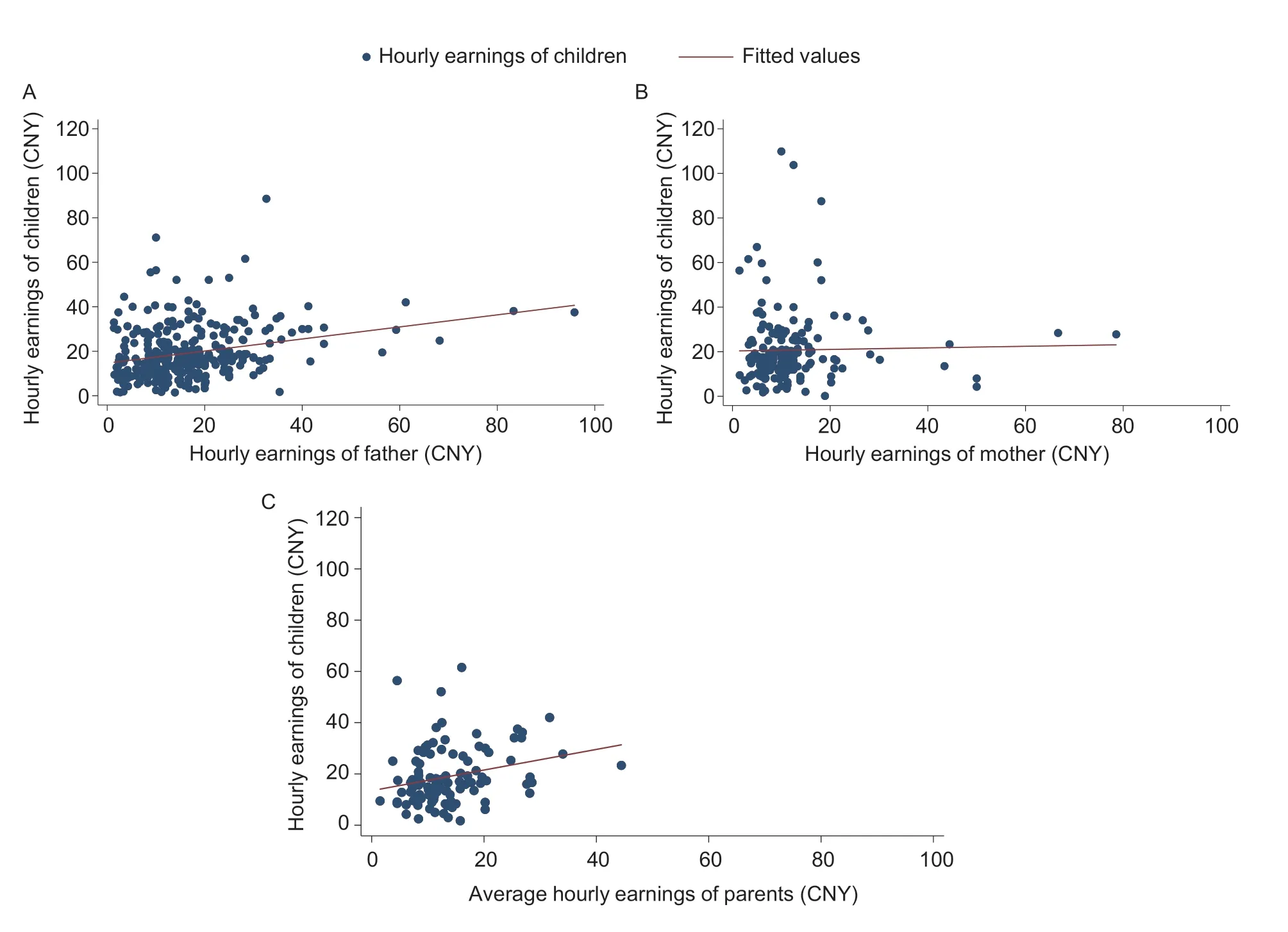

Fig.1 showed the hourly earnings of parents and their children. According to our data,the average hourly earnings of the children was 19.2 CNY in 2018. The father’s average hourly earnings was 16.8 CNY in the same year. The average earnings of the mother was 13.0 CNY. The average earnings of father was approximately 1.3 times as much as the wage of mother in rural families,which was much smaller than those in the literature (Liet al.2013; Wanget al.2019). The finding indicated the healthy development of the Chinese rural labor market.

In Fig.1,the hourly earnings of children increased with the rise in the father’s hourly earnings,which implied an obviously positive correlation between the earnings of fathers and their children (Fig.1-A). The correlation coefficient between hourly earnings of children and father’s hourly earnings was 0.118 (P<0.01,R2=0.02). However,the relationship between mothers’ and their children’s hourlyearnings had a weak positive correlation compared with that of the father and children (Fig.1-B). The correlation coefficient between hourly earnings of children and mother’s hourly earnings was 0.018 and it was not significant even at 10% level (R2=0.002). This finding indicated that the hourly earnings of the mother might have a slight influence on the hourly earnings of her children. The correlation between the average hourly earnings of parents and their children was also positive (Fig.1-C). The correlation coefficient between average hourly earnings of children and average hourly earnings of parents was 0.027 and it was not significant even at 10% level (R2=0.003).

Table 1 Description of the variables

Fig.1 Relationship of hourly earnings between parents and their children.

3.2.OLS model of intergenerational transmission of earnings

According to the OLS estimation,there was a positive relationship between parents’ and their children’s hourly earnings (Table 2). We found that the impact of the father–children transmission effect was 0.226 (P<0.01),which meant that each 1% increase in the father’s hourly earnings would on average lead to an approximately 0.226%increase in their children’s hourly earnings (row 1,column 1).When we controlled individual characteristics,this effect reduced to 0.213 (P<0.01) (row 1,column 2). When we further controlled regional factors,we found the magnitude of the transmission effect declined to 0.202 (P<0.01) (row 1,column 3). The mother’s hourly earnings had almost no effect on their children’s hourly earnings,which was consistent with that in descriptive analysis.

However,the impact of parents’ average hourly earnings on children’s hourly earnings was positive and much stronger than that of the father’s or mother’s alone. This result showed that each 1% increase of parents’ hourly earnings on average added approximately 0.287% of children’s hourly earnings (P<0.05) (row 3,column 7). When we further controlled other covariates,the transmission effect remained significant,and the magnitude increased to 0.373 (P<0.01) (row 3,column 9).

Children’s hourly earnings were also correlated with other characteristics. Years of schooling of the children had a significant positive effect on their hourly wage (P<0.01) (row 4,columns 3,6,and 9). This finding was consistent with those in the literature,but the magnitudes of the coefficient were larger in this study (Liet al.2005; Zhanget al.2008;Wanget al.2019). It further indicated that human capital was playing an increasingly important role in wage,which proved the healthy and equitable development of the Chinese labor market. Males had much higher wages only in model (1)(P<0.01) (row 6,column 3). Although we considered the effects on the children’s hourly earnings on the basis of the background of the average earnings of a parent or parents,there was no significant difference in the earnings between the male and female children (row 6,column 9). Age also had a significant and positive effect on the hourly earnings(P<0.01) (row 6,columns 3,6,and 9). If the age increased1 year,hourly earnings rose approximately 0.022–0.052%.The number of vocational qualification certificates and job location had positive and negative effects on the hourly earnings,only in models (1) and (2),respectively (rows 7 and 9,columns 3 and 6). Self-reported physical health had positive and significant effects on hourly earnings,implying the vital role of human capital -on education and physical health -in the earnings.

Table 2 Intergenerational transmission of earnings in rural China

3.3.Discussion on the results of OLS regression

Our study found that the estimated effects of the father’s hourly earnings -consistent with in the literature -demonstrated that higher-earning fathers increased their children’s hourly earnings. The result was lower than other studies that used the Chinese urban sample (Gonget al.2012; Denget al.2013). The implication was that intergenerational mobility was higher for individuals born in rural parts of China,which was consistent with the logical deduction of Gonget al.(2012).

However,in the literature that has used an urban sample,a significant intergenerational transmission of income between mother and children was observed. For example,Denget al.(2013) found that income persistence for the children–mother pairs was 0.340 for 1995 and 0.448 for 2002. Gonget al.(2012) found that the intergenerational income elasticity of mother–son and mother–daughter was 0.369 and 0.338,respectively. The hourly earnings among rural females were more homogeneous than that of males or that of urban females,which led to a slight effect on their offspring’s hourly earnings. The small sample size may also have an effect.

Although the results of our study showed that average hourly earnings of both parents played a stronger role than the father’s or the mother’s hourly earnings alone,the coefficient of the average hourly earnings of both parents was not comparable to the coefficients of the father’s or the mother’s hourly earnings individually. The average hourly earnings of both parents when increased by 1%was equivalent to both the father’s and the mother’s hourly earnings increasing by 1%. Thus,both parents’ average hourly earnings played a stronger role than either the father’s or the mother’s hourly earnings. Compared with the relationship of father’s or mother’s and their children’s hourly earnings,the correlation of average hourly earnings of parents and their children controlled assortative mating,avoids multicollinearity,and produces more precisely estimated relationships.

Potential endogeneity is a limitation of the OLS model.In our case,this limitation affected our study when parents and their children are linked by similar genetics and family culture. This connection between the generations may bias the results in a manner that tends to overstate the effect of the parents’ earnings on their children. In other words,it is statistically significant that children following a similar path to their parents,but the OLS model may describe this only as being a feature of intergenerational transmission rather than a combination of similar genetics and family culture.The family fixed effect (FFE) model is an effective method to address this type of potential endogeneity (Donget al.2019).Due to the limited sample,we cannot use the FFE model to estimate the transmission effect of parents’ earnings on their children’s earnings while eliminating these other contributing factors that affect both parents and their children.

4.Mechanism of ITP

4.1.Parent’s earnings and the human capital of their children

We attempted to find the mechanism of ITP by identifying the relationship between parent’s earnings and the children’s human capital because human capital have gradually become the main determinant of the children’s earnings.According to the literature,aspects of human capital were,for example,formal education in school,skills training,and physical and mental health. Due to the limitation of the data,we were only able to identify the relationship between parents’ earnings and formal education in school,skills training,and physical health. The human capital of children was related to the whole-family characteristics. Thus,we mainly analyzed the relationship between the average hourly earnings of parents and the human capital of their children.

In Table 3,average hourly earnings of parents were positively correlated with the years of formal schooling of their children. If the average hourly earnings of parent’s increased by 1%,the years of formal schooling of their children increased by 1.367 years (row 1,column 1).When we controlled other variables,such as gender,siblings,and birth order,that affected education,the result remained robust (row 1,columns 2 and 3). We also observed a significant positive correlation between parents’average hourly earnings and the duration of skills training of their children while controlling the covariates (row 1,columns 5 and 6). However,no significant relationship was observed between the average hourly earnings of parents and the children’s self-reported physical health.The results indicated that high hourly earnings can be intergenerationally transmitted by improving the children’s human capital,especially education and skills training.In other words,improving the human capital of children facilitated breaking the of ITP.

Table 3 Effect of parents’ earnings on the human capital of their children

Notably,the regressions did not demonstrate that the current average hourly earnings of a parent was a determinant of their children’s human capital. However,according to the literature,the current earnings were significantly affected by previous earnings (Durlauf 1996;Heckman and Vytlacil 1998; Geweke and Keane 2000;Islam 2013). Thus,the children in families with current high-earning parents will logically have high human capital.

4.2.Parents’ earnings and their investment in the human capital of their children

We further described the relationship between the earnings of parents and the schooling investment in their children before the children participated in the labor market to find their logical relationship. To achieve this objective,we used the sample for which we have documented parents’expenditure on schooling in each survey. Schooling investment includes fees for tuition,incidentals,books,and courses and others,such as tutorial fees for courses.

The results showed that parents’ hourly earnings had a positive significant correlation with the expenditure on schooling in each survey year; however,the sample was very small in each survey (Table 4). Specifically,the schooling investment in 2015 increased by 1.9% if the hourly earnings of parents increased by 1 CNY (P<0.1) (row 1,column 1). If the hourly earnings of parents increased by 1 CNY,the schooling investment in 2007 and 2004 increased by 2.4 and 6.3%,respectively (P<0.1,P<0.05) (row 1,columns 2 and 3).

4.3.Case studies on ITP

We exploited three cases to further analyze three types of ITP and their mechanisms. These three cases were drawn from those who had just started primary school in 2005 and participated in off-farm employment since 2018,which supported us to clearly state the mechanism of intergenerational transmission of earnings from the human capital perspective. The three cases described the role of investment in human capital in escaping from ITP,being caught in the ITP,and persisting intergenerational earnings.

All of these cases demonstrated the importance of investment in children’s education and skill training before their participating in labor market. If the children were invested in education or skill training more before participating in labor market by their parents,they were more likely to earn higher than their parents and had better social welfare,such as pension,medical insurance,and promotion opportunities. If the children were invested less in education or skill training in their school period,they usually faced more challenges in obtaining a steady job in the formal sector and earning higher wages than their parents. With the economic development and increasinglycompetitive labor market,only the offspring was invested more than their parents,they might escape from or persist in the intergenerational transmission of earnings. The detailed case stories are shown in Appendix A.

Table 4 Effect of parents’ earnings on the schooling investment in children

In Section 4,we combed for the paths of ITP by identifying the relationship of parents’ earnings and their children’s final human capital before participating labor market and estimating the impact of parents’ earnings on their investment in children’s schooling when the children being in school. This analysis went through the whole chain from children’s schooling to their labor participation. Using the quantitative and qualitative methods,we proved the cycle of parents’ income–human investment–offspring’s income using a uniform sample. The results implied that it was very difficult to escape from ITP for the children of poor families.The visionary parents and enough money are the necessary rather than sufficient conditions. Although there is a formal financial aid system of education for poor families in rural China,the funding intensity and parents’ cognition of utilizing the funding to support children’s schooling,especially before entering college,are both the important factors affecting the final human capital outcomes.

5. Conclusion

This paper used five waves of panel data with 2 000 households spanning more than 15 years to analyze the intergenerational transmission of earnings. Using quantitative and qualitative methods,we found an obvious intergenerational transmission of earnings in rural China,especially for the intergenerational transmission between the earnings of father and children and average earnings of parents and their children.

Along with the intergenerational transmission of earnings,human capital played a vital role in increasing the earnings of children. The regressions demonstrated that parents’earnings were positively and significantly correlated with the years of formal schooling and the duration of skills training of their children. The results indicated that the high earnings would be intergenerationally transmitted by improving the children’s human capital,which helped break the ITP.

Using the small sample with the information on the schooling investment in the surveys,we performed quantitative analysis and found that parents’ earnings had a positive significant correlation with the expenditure on schooling of the children. This finding implied that parents with high earnings were more likely to invest their children’s human capital,which further improved the earnings of their children. We explored three cases in our sample by combining school history and current employment performance. The cases showed that investing in children’s human capital could accelerate their capacity to obtain a high income and promotions.

Compared with that in urban areas,the intergenerational transmission of earnings in rural China was much lower,which indicated that the income mobility in rural areas was higher. It implied that it was a breakthrough in focusing on intergenerational transmission of earnings in solving relative poverty in China after 2020. It also showed that increasing rural household income by investing education would gain greater social benefits in rural areas since it promoted the upward mobility easier than that in urban China.

In South Asia,Africa and developing countries in other parts of the world,parental background -especially income-matters the most for the prospects of the offspring.The findings of this study on China may help understand the ITP of other developing countries. Even though the next generation’s economic status will depend on more factors than education,such as the efficiency and fairness of factor markets,education is likely to continue to play a key role in economic mobility across generations. Some measures implemented in China,like compulsory education law and the financial aid system of education for poor families,may be extended to other developing countries and may effectively help them break the ITP.

This was the first study to identify the ITP in rural China from the perspective of analyzing the intergenerational transmission of off-farm earnings and found its mechanism by using a mixed method based on long-term tracking data. However,we did not identify the causal effect by using another method,such as FFE or IV,because of the limited sample. Additionally,the multiple effects of human capital investment on the children and their heterogeneous,such as on employment quality,family welfare,vocational promotion,and so forth,require further exploration. If the data are available,further research will produce valuable information for literature.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71903185 and 71661147001),the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA20010303),and the National Social Science Fund of China (18ZDA005). We thank the Ph D students and research assistants of UNEPInternational Ecosystem Management Partnership (UNEPIEMP) for collecting data.We appreciate the time and effort of numerous local officials,village leaders,and farmers in our sample areas for their assistance with our survey.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendixassociated with this paper is available on http://www.ChinaAgriSci.com/V2/En/appendix.htm

杂志排行

Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- Paths out of poverty

- The power of informal institutions:The impact of clan culture on the depression of the elderly in rural China

- Does empowering women benefit poverty reduction? Evidence from a multi-component program in the lnner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China

- The impact of the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme on the“health poverty alleviation” of rural households in China

- The effects of social security expenditure on reducing income inequality and rural poverty in China

- Synthesize dual goals:A study on China’s ecological poverty alleviation system