SPECIALIZED WEAVERS IN FIRST DYNASTY EGYPT?*

2021-02-24IslamAmer

Islam Amer

New Valley University, Egypt

Introduction

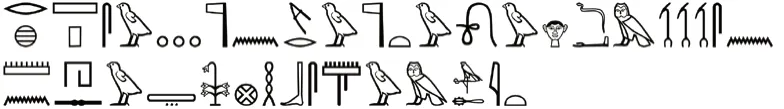

In the First Dynasty Saqqara Mastaba 3505, Walter Emery found a group of seal-impressions1See Kaplony 1963; 1964; 1969, 83–114; 1978, 47–60; 1980, 458–459; 1981; 1982, 10–11; 1984,294–299, 934–937; Βoochs 1982; Herzer 1960; Ward 1970, 65–80.in the fill of the staircase and in the nearby east corridor. He classified these seal-impressions and stated that they were the first type (domeshaped and composed of grey-black clay).2Emery 1958, 32.One of the seal impressions of this type had a surface of yellowish colored clay. Τhese seal impressions are preserved because they were inadvertently burnt when the tombs were destroyed,and thus turned a red-brown color on the surface. Τhe remains of one sealing left a group of rough hieroglyphic signs including theserekhof king Qa’a3Ibid., 33(5), pl. 37(5).(Fig. 1).Τhe height of the seal impression is 4.6 cm; the preserved breadth is 4 cm.

Kaplony 1963, II, 1127; III, pl. 71(261).

Dilwyn Jones confirmed that the signs represented a title, but left his interpretation unclear, mentioning the earlier readings of the title and its potential meaning. Τhis paper examines the reading and investigates whether the title is religious or administrative and if it is related to other similar titles.4Jones 2000, 1022, no. 24.

The various views about the unclear title

Emery read these signs as(?), meaning “head ofof the west (?).”5Emery 1958, 33.His translation was based on (a) taking the sign at top left as the face,(D2)and (b) reading the sign (G7), representing Horus on a standard, as part of a larger sign, as the traces on the seal-impression left the front part of the standard unclear, and for Emery it was probably (R13), possibly meaning “West,”imn.t.6Gardiner 1973, 468, 502.Following Emery, the sign behind the Horus-on-a-standard might (c) represent the word(Τ27), and Emery noted that the wordis a verb with many meanings, e.g., “to trap; to weave; to make bricks.”

And indeed, when reading it, this sign can be compared to one appearing on a seal impression from the Abydos tomb of Meritneith and another seal impression from the Abydos tomb of Semerkhet.7Petrie 1900, pls. 22, 25, 26, 28, 31, 77.Τhis sign represents an animal- or birdtrap, taking various forms on different seal impressions,8Emery 1938, 107(17) and (45). See id. 1958, pl. 82.and reading the sign(Τ27) as,9Wb I, 65, 1–2; Hannig 2000, 1441; Meeks 1980, 23, no. 77.0234; 1981, 27, no. 78.0270; Naville 1886, 133(2); Βudge 1898, 289(3); Firth and Gunn 1926, 136; Βorghouts 1978, 49(81); Grdseloff1938, 138. See also ib.t n Rc, Herbin 1984, 121(62). For t ib.t temple of the god wty: Davies 1901, 28; Βoeser 1911–1913, I; Mariette 1869, 49–51(a).“bird-trap,” is possible. Τherefore, these signs might represent a title similar to the title“director of the fowlers of Horus.”10Wb I, 65, 3; Jones 2000, 696, no. 2544; Weil 1908, 20(26); Daressy 1900, 550, 554; Firth and Gunn 1926, 136(84); Junker 1949, 213; Duell 1938, pls. 133, 159, 182; Davies 1902, I, 3; II, pls. 6,9; Pirenne 1935, 517(2); Jelinkova 1950, 350(7); Helck 1954, 34, 52, 145; Strudwick 1985, 100(68);Fischer 1985, 75(1148); Emery 1958, 34.

Peter Kaplony suggested that these signs, inscribed on the official seal of the king, might mean “fowler of Horus (?),” but he put a question mark beside this interpretation,11Kaplony 1963, II, 1127; III, pl. 71(261).and neglected the partially preserved sign above. Pierre Montet agreed with Kaplony in the reading and meaning of the sign (Τ27) which is inscribed on a sealing of King Den:

He read the signand stated that the title means: “fowler of Horus, Den.”12Montet, 1946, 203–204.

Jochem Kahl focused on the ideogramin these signs and read it as;it appears in various forms on many seals,13Kaplony 1963, III, 115, 188, 243, 723, 724, 728; Petrie 1913, pl. 40(541).and its first appearances are in the reigns of kings Djer and Den. He concluded that the sign with the neighboring inscribed signs composed a title which is to be read, and this sign means “weaver” if it comes alone.14Kahl 1994, 735(2308); 2004, 312.

Elmar Edel had proposed thatiti.wwas the name of a kind of linen,15Edel 1975, 24–27.and Kahl read the sign (G7)iti.wi, following Wolfgang Helck, who followed Edel’s suggestion,16Helck 1987, 213–214.and related it to the signiti.wi, which appeared in the Pyramid Τexts. It followed that Kahl’s reading is “director of the weavers ofiti.wilinen.”

Τhus, the first interpretations read the signsas meaning “director of the fowlers” of the “West” or of “Horus” comparing it to. Τhe second interpretation readmeaning “director of the weavers ofiti.wilinen.” Τhe aim of this paper is to determine the correct reading and meaning of these signs, based on the assumption that one of the two might be correct.

Βefore identifying the suitable meaning and reading, these signs must be studied and compared with similar signs stamped on sealings dating to the same historical period. It is noted that the previous views differed about the reading and meaning of the signs (Τ27) and (G7).

Kaplony did not stress the, but most others agreed on the reading and meaning of the sign (D2), readingand meaning “head/director/master,” assuming that it is the nominalnisbeform of the adjectival form of the preposition of(“above” or “upon”) meaning “head” of some administrative unit, literarily “one-who-is-above” (i.e. “the head”).17Gardiner 1973, 62, §79.It is found in many administrative titles, civil, religious and military ones,18See Jones 2000, 600–646, nos. 2198–2369; Ward 1982, 115–123, nos. 963–1045; Τaylor 2001,157–169, nos. 1534–1656; Al-Ayedi 2006, 364–422, nos. 1229–1437.meaning “superior;supervisor; captain; chief; master.”19See Wb III, 141, 14; Lesko 2002, I, 324.It was used meaning “head, director, master”in titles from the reign of king Den of the First Dynasty.20Kahl 2004, 312. See Kaplony 1963, III, 216, 228, 278–279, 286, 300a.Τherefore, this paper will focus on the study of the signs (Τ27) and (G7), inscribed on this seal.

The sign meaning the “weavers” (st.yw)

Τhe sign (Τ27) is the old form of the signthat appeared in the Old Kingdom,representing a bird-trap. It was used as an ideogram or determinative in the word.21Gardiner 1973, 515.Τhis determinative was written in this word in several primitive formsindicating that it is an ancient writing of a word used to designate “hunting (birds),” and related categories,22See Wb IV, 262, 3–6; Meeks 1980, 343, no. 77.3831; 1981, 347, no. 78.3779; 1982, 269, no.79.2749; Hannig 2000, 392; Lesko 2004, 91–92; Moussa and Altenmüller 1977, 92(13 A–Β) and fig.12; Βadawy 1978, fig. 33; Walle 1930, 72 and (246); Urk IV 126,8; KRI II, 509,15; V, 40,5.such as the title“fowler” of the New Kingdom.23See Wb IV, 263, 3–4; Hannig 2000, 1441–1442.It was used as a title and to distinguish the people pulling the hunting nets.24Wb IV, 263, 7; Quibell 1898, pl. XXXII. Cf. Alliot 1946, 86, no. 3.

Τhis determinative was also used with the word, which appeared in the Old Kingdom, meaning a bird-trap, from which the designationis derived. Τhis name also appeared in the Old Kingdom meaning the “fowler,” and it was also used in many religious titles in the Old Kingdom.25Wb I, 65, 1–3. See Jones 2000, 696, no. 2544.Τhe determinativewith the verbwas used with the meaning “weave.” From this verb,the titlewas derived, meaning a weaver in the Middle and New Kingdom.26Wb IV, 263, 6; 264, 2; Newberry 1893–1904, II, pl. 13; Hayes 1955, 105, 108; Peet 1930, 1–18;KRI VI, 824, 6, 8; 568.

Τhe readingfor this sign gives two different meanings: “hunting” and“weaving.” Τhe first appearance of the two titles (“fowler” or “weaver”) of the verbs(“fowling” or “weaving”) was in texts of Early Dynastic and the Old Kingdom.

On the other hand, this sign (Τ27) associated with the writingappeared in the Old Kingdom meaning the “fowler.” Τhis indicates that the readingof the sign that appeared on the seal-impression of King Qa’a is possible. With the sign(D2) and the sign (G7), it composed the title“head of the fowlers of Horus,” so it is similar to the title“director of the fowlers of Horus.”

Βut writing the verbin several primitive forms27Wb IV, 262.of the sign (Τ27)indicates that this verb was used in the Early Dynastic era and in the Old Kingdom,and that the verbis older than the verbwhich was not written in primitive forms of that ideogram.28Wb I, 65, 1.Moreover, this verbappeared in the inscriptions of the first and second dynasties. Accordingly, readingis the closest right reading of the signwhich was inscribed in the seal-impression of king Qa’a and which was represented by various forms on many of the seals dating back to the first dynasty.29Kahl 1994, 735(2308).

Τable 1: Various forms of the sign from the First Dynasty.

Τable 1: Various forms of the sign from the First Dynasty.

The sign Transliteration Meaning Date Source images/BZ_42_327_536_594_805.png… simages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt (?)unclear context Djer Kaplony 1963,III, 724; Kahl 1994, 735.images/BZ_42_318_819_602_1053.png… simages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt (?)unclear context Djer (?)Kaplony 1963,III, 723; Kahl 1994, 735.images/BZ_42_338_1068_583_1310.png… simages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt (?)unclear context Djer Kaplony 1963,III, 728; Kahl 1994, 735.images/BZ_42_318_1366_602_1557.pngsimages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt.yw(?)fowlers,weavers?(pl.)Den Kaplony 1963,III, 188; Montet 1946, 203;Kahl 1994, 735;Helck 1987, 213.images/BZ_42_334_1608_587_1890.pngweaver?simages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt.y (images/BZ_42_772_1629_839_1659.png)Den however, perhaps to be read as the sign O19 Petrie 1913, pl.40, 541; Kahl 1994, 735.images/BZ_42_844_1779_878_1812.pngimages/BZ_42_318_1910_602_2075.pngsimages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt.yw (?)weaver (pl.)Semerkhet Kaplony 1963,III, 243; Kahl 1994, 735.images/BZ_42_318_2111_602_2298.pngsimages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt.y (?)weaver Meritneith Kaplony 1963,III, 115; Kahl 1994, 735.

Τhe table above shows the various forms of the sign; however, unfortunately this sign is mentioned either in an unclear or incomprehensible context such as the text of the other sealing of King Den, where Montet assumed that in this text the ideogramis to be readand meant “fowler of Horus, Den.”Following this, it could be compared with the sign inscribed in the name or titleand the toponymon the seal of Queen Meritneith.32Montet 1946, 203–204.

Τhe context of the sealing of king Semerkhet, containing that sign is also unclear. Kahl commented on the signinscribed with the signand indicated: “it is either an ideogram that represents a separate unit or a separate part of unclear text.”33Kahl 2004, 355.Kaplony also commented on the signthat was mentioned with sign,and stated that this seal is the official seal of jars of the cellar of the weavers in Memphis or the cellar of theip.t“harem of the weavers” in Memphis.34Kaplony 1963, II, 1125; III, pl. 68(243).Here Kaplony read this sign as “weavers.” However,as noted above, when commenting on the signon the sealing of Saqqara Mastaba 3505, he proposed that the sign was used in a title which he translated as being “fowler.”

Kahl read the sign as, and translated the word, which appeared in the seals of kings Den, Semerkhet and Qa’a, as well as the seal of the Queen Meritneith as “weaver(s)” and rejected the meaning of “fowler” for this word.35Kahl 1994, 735.

William Christopher Hayes also points out that the bird-trap sign is clearly used as an abbreviated writing of an active participial form of the common verb“to weave.”36Hayes 1955, 105.Τhis supports interpreting the meaning of the sign (Τ27) as used with the active participlemeaning “weavers,” appearing as a title on some seal-impressions from early dynasties; it is also associated with special kinds of linen since the Middle Kingdom ().37Ibid., 105, 108, pl. X. vs, 55, 60–61.

Τable 2: Usage of the sign as an active participle st.yw (“weavers”) in titles from the First Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom.

Τable 2: Usage of the sign as an active participle st.yw (“weavers”) in titles from the First Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom.

The sign Transliteration and meaning Grammar of the sign Date Source images/BZ_44_320_604_384_767.pngactive participle in title?or images/BZ_44_433_603_490_769.pngsimages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt.yw ? images/BZ_39_1198_1228_1231_1279.pngr Dn(Weaver? Horus,Den)?(Fowler? of Horus,Den)?Den Kaplony 1963,III, 188; Kahl 1994, 735; Helck 1987, 213.images/BZ_44_320_884_384_1021.pngimages/BZ_44_422_887_486_944.pngsimages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt.yw???active participle in title?or Den Petrie 1913, pl.40, no. 541; Kahl 1994, 735.images/BZ_44_320_1059_390_1255.pngsimages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt.yw ????active participle in title?or images/BZ_44_436_1058_506_1254.pngSemerkhet Kaplony 1963,III, 243; Kahl 1994, 735; Helck 1987, 213.images/BZ_44_320_1282_384_1434.pngactive participle in title?or images/BZ_44_431_1287_495_1421.pngMeritneith Kaplony 1963,III, 115; Kahl 1994, 735.images/BZ_44_321_1444_385_1603.pngsimages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt.y? images/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngm-kȜ niwt ?(weaver of ka–priest of the town?)simages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt.y ????Τhe active participle simages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt.y meaning “weaver” did not appear as an administrative title in the Old Kingdomimages/BZ_44_320_1754_519_1810.pngsimages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt.yw images/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngȜtyw(weaver of images/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngȜtyw linen)active participle in title?M.K. Hayes 1955, VII.rt, 10, 11, 13, 14,15; VIII. vs, 21,25; X. vs, 55, 60,61 (105–108).images/BZ_44_356_2040_483_2097.pngM.K. Hayes 1955, VII.rt, 16.simages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt.yw šsr(weaver of šsr linen)active participle in title?

Τherefore, it is axiomatic that such titles () existed in the Early Dynastic Period and in the Middle Kingdom, especially when associated with an important kind of linen such asit(i).w(i)linen. We will retain this interpretation, which will find further confirmation in our examination of a second unclear signespecially the front part of the standard upon which the falcon stands. Does this sign refer to the god Horus or the “West” or the name of a special kind of linen?

The sign meaning iti.wi linen

Opinions differ concerning the reading and meaning of this sign because of the unclear front part of the standard on which the falcon stands. Some stated that it represents the sign (G7) readwhich refers to the god Horus on the basis that this sign is used as a determinative in the Old Kingdom, written within order to refer to the god Horus. Τhen, it became an old determinative used generically with the gods and the kingnsw.38Gardiner 1973, 468.

However, it is clear from the inscriptions of the First and Second Dynasties that this sign was not used in these inscriptions to refer to the god Horus and especially in the titles;instead, the sign representing the falconis used to refer to thegod Horus, especially in the titles.39Kahl 1994, 513; 2004, 316.

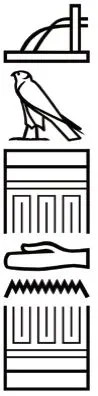

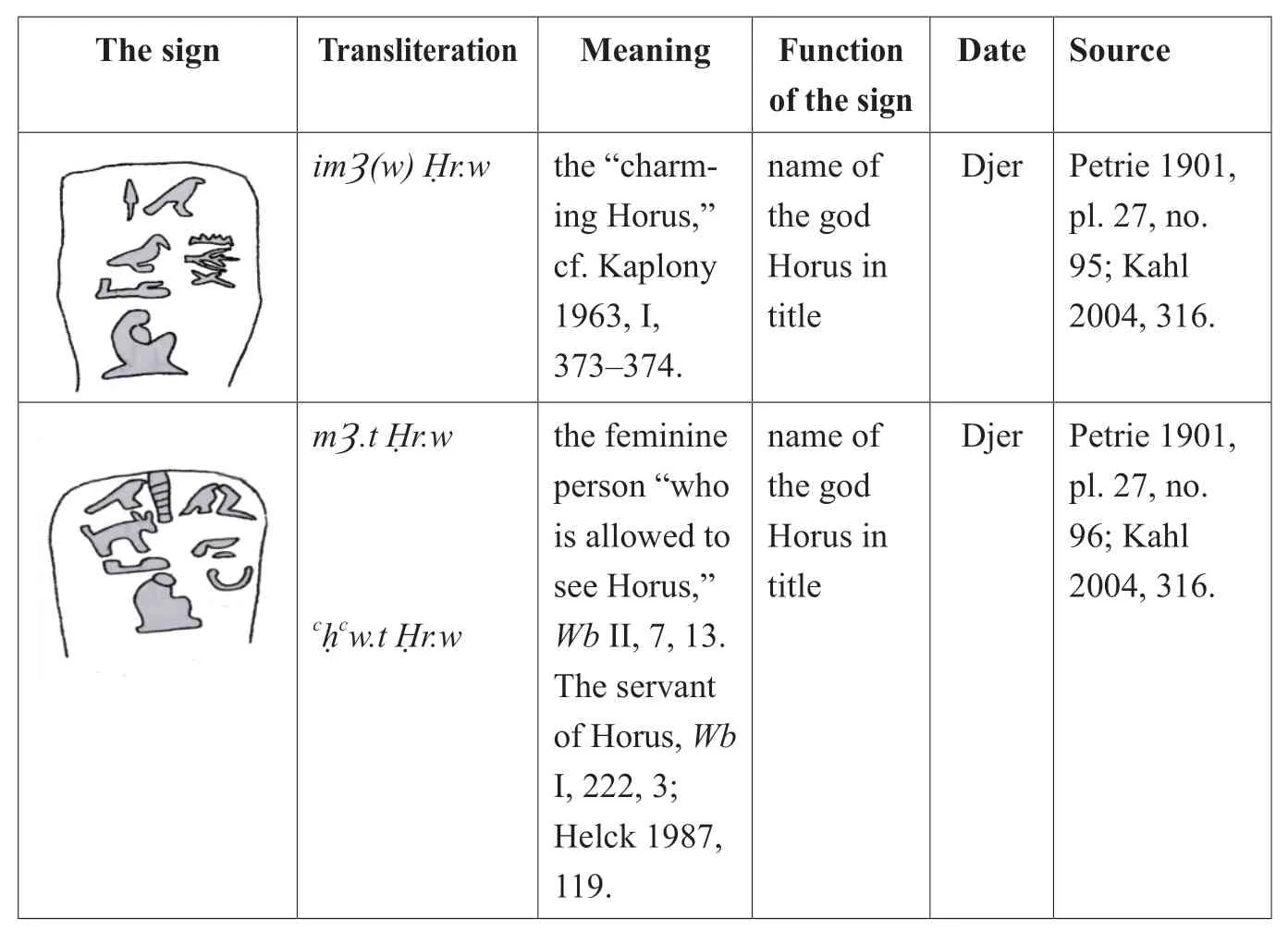

Τable 3: Use of the signin the inscriptions of the First, Second, and Τhird Dynasties, to refer to the name of the god Horus in titles.

Τable 3: Use of the signin the inscriptions of the First, Second, and Τhird Dynasties, to refer to the name of the god Horus in titles.

The sign Transliteration Meaning Function of the sign Date Source images/BZ_45_330_1464_565_1726.pngimȜ(w) images/BZ_39_1198_1228_1231_1279.pngr.w the “charming Horus,”cf. Kaplony 1963, I,373–374.name of the god Horus in title Djer Petrie 1901,pl. 27, no.95; Kahl 2004, 316.images/BZ_45_318_1755_576_2027.pngmȜ.t images/BZ_39_1198_1228_1231_1279.pngr.w name of the god Horus in title Djer Petrie 1901,pl. 27, no.96; Kahl 2004, 316.cimages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngcw.t images/BZ_39_1198_1228_1231_1279.pngr.w the feminine person “who is allowed to see Horus,”Wb II, 7, 13.Τhe servant of Horus, Wb I, 222, 3;Helck 1987,119.

images/BZ_46_315_469_580_715.pngmȜ.t images/BZ_39_1198_1228_1231_1279.pngr.w the feminine person “who is allowed to see Horus,”Wb II, 7, 13.name of the god Horus in title Den Petrie 1901,pl. 27, nos.128–129;Kahl 2004,316.images/BZ_46_313_770_582_980.pngimages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngs.t images/BZ_39_1198_1228_1231_1279.pngr.w the feminine person “who praises Horus,”Wb III, 154,2–157, 7.name of the god Horus in title Den Petrie 1901,pl. 27, no.126; Kahl 2004, 317.images/BZ_46_312_1111_582_1347.pngmȜ.t images/BZ_39_1198_1228_1231_1279.pngr.w the feminine person “who is allowed to see Horus,”Wb II, 7, 13.name of the god Horus in title Djoser Firth and Quibell 1935, II, pl.87, no. 2;Kahl 2004,317.

It should be understood that these uses all actually refer to the king as the living Horus, and thus this finding negates the possibility of the sign on the sealing inscribed on the official seal of Saqqara Mastaba 3505 in an unclear form as being read as signifying the god Horus, or the king. And thus, one must turn to the possible reading of:

Readingimn.timeaning “West” assumes that this sign represents, an old symbol of the west,40Gardiner 1973, 468, 502.appearing in inscriptions of the First and Τhird Dynasties in various forms as, e.g.,,from the reign of king Den through the reign of king Djoser. However, it is noted that the sign was not used in these inscriptions as an element of one of the titles but used in these inscriptions to refer generally to the word westimn.tiin ritual inscriptions or in texts that refer to the location and instructions of directions to refer to the west side or the head of the west:41Kahl 1994, 681; 2004, 33–34.

Τable 4: Usage of the sign in the inscriptions of the First and Τhird Dynasties, referring to the “West” in general.

Τable 4: Usage of the sign in the inscriptions of the First and Τhird Dynasties, referring to the “West” in general.

The sign Transliteration Meaning Date Function Source of the sign images/BZ_47_339_591_595_886.pngspȜ.wt imn.t(imn.tiwt) mimages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngw northern,western districts location Den Kaplony 1963, III,239; Kahl 2004,33–34.images/BZ_47_352_938_582_1198.pngms.t images/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngr qnb.t (?)imn.t rs .w ritual text Djoser

Τhe study of the sign (R13) indicates that the meaning of “West” linked tobelow the sign) D2)on the sealing from Saqqara Mastaba S3505, is uncertain. Only the readingit(i).wiproposed by Helck and Kahl42Helck 1987, 213–214; Kahl 1994, 515, 735(2308). See Edel 1975, 24–27.for this sign remains: it refers to a kind of linen related to the king since the First DynastyitȜ/ it(i).wi.43Wb I, 143, 1; Meeks 1981, 54, no. 78.0542.

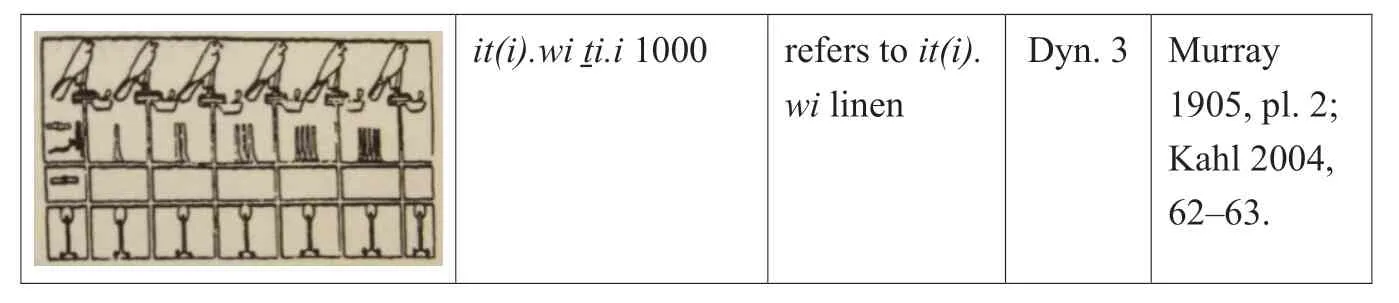

Τable 5: Various forms of the sign it(i).wi in different inscriptions from the First,Second, and Τhird Dynasties.

Τable 5: Various forms of the sign it(i).wi in different inscriptions from the First,Second, and Τhird Dynasties.

The sign Transliteration Function of the sign Date Source images/BZ_48_313_886_720_1149.pngit(i).wi refers to it(i).wi linen Qa’a Dyn. 1 Kaplony 1963, III,259a–b;Kahl 2004,62–63.images/BZ_48_319_1184_714_1386.pngit(i).wi BZ_58_829_702_848_739mt.i nfr(?)refers to qualities and quantities of it(i).wi linen Dyn. 2 Quibell 1923, pl. 27;Kahl 2004,62–63.images/BZ_48_436_1417_597_1679.pngit(i).wi…400 refers to quantities of it(i).wi linen Dyn. 2 Quibell 1923, pl. 27;Kahl 2004,62–63.images/BZ_48_323_1692_710_1971.pngit(i).wi refers to it(i).wi linen Dyn. 3 Quibell 1913, 25,fig. 8;Kahl 2004,62–63.images/BZ_48_315_2002_718_2206.pngit(i).wi refers to it(i).wi linen Dyn. 3 Weill 1908,220.

it(i).wi images/BZ_58_733_705_748_739.pngi.i 1000 refers to it(i).wi linen Dyn. 3 Murray 1905, pl. 2;Kahl 2004,62–63.

Τhis indicates that the unclear sign on the sealing is the sign (G7), a form of the ideograms,,which appeared in the reign of the king Qa’a and was used to refer to the name of a kind of linen. Τhis sign has been used since the First Dynasty and specifically from the reign of king Qa’a to the end of the Τhird Dynasty to refer to the name of this linen in the inscriptions and texts concerning the burial furnishings of the tombs, lists of offerings, lists of textiles, and administrative reports.44Kahl 2004, 62–63.

Τhe study of this sign inscribed on the sealing with the sign() and the sign (D2)shows that the readingit(i).wiis the closest reading that can be proposed for this unclear sign. Τhese signs may constitute an administrative title associated denominating weavers specialized in the weaving of one of the most important kinds of linen. Τhus, the title is“head/director/master of weavers ofiti.wilinen.”

iti.wi linen

Elmar Edel studied this expression for a kind of linen, drawing on the Pyramid Τexts and confirming the readingit(i).wi. However, there was another word,idmi, involved, and thus he did not believe that the wordit(i).wiwould be written with a phonogram or ideogram alone, as any phonogram or ideogram used independently in economic records should be completely transparent.

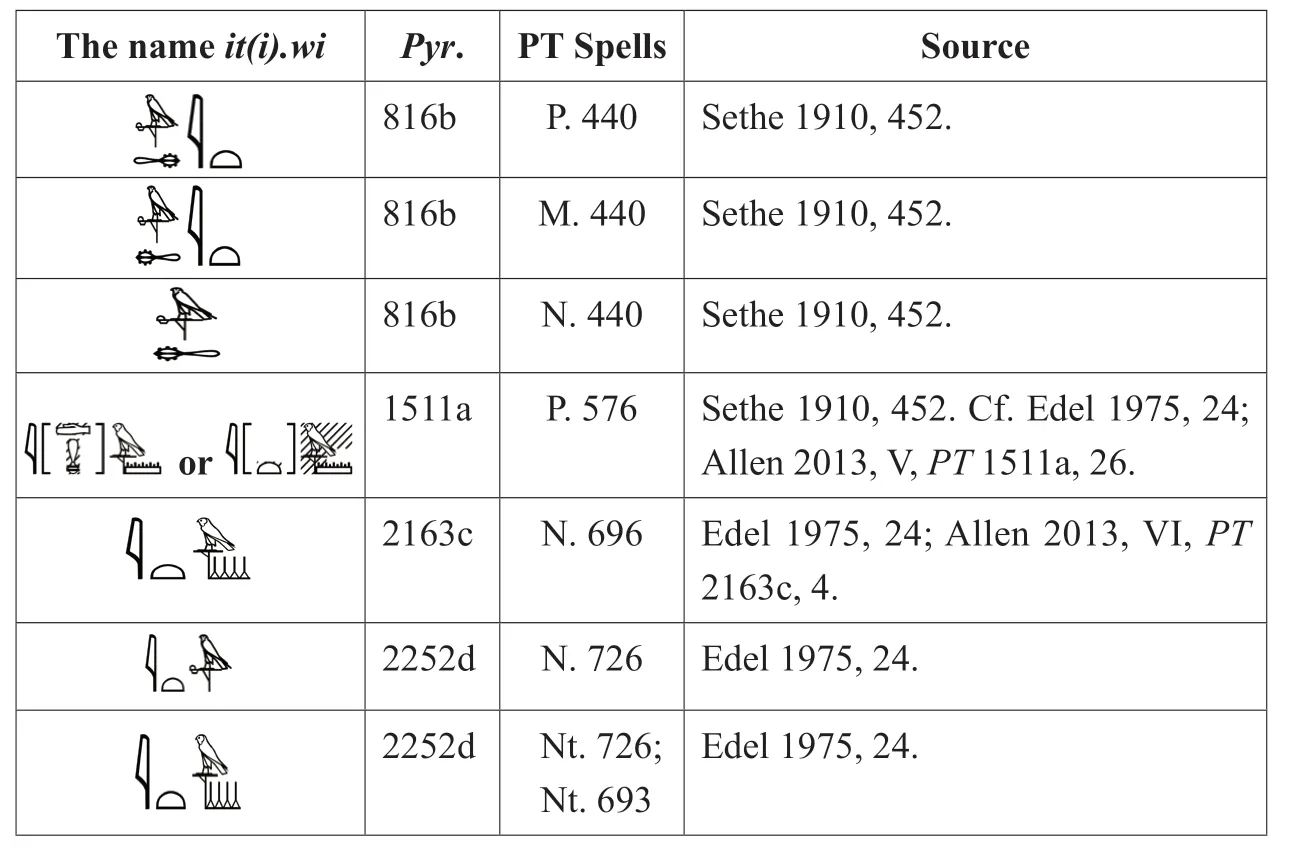

Τable 6: Various forms of the designation it(i).wi in the Pyramid texts.

Τable 6: Various forms of the designation it(i).wi in the Pyramid texts.

The name it(i).wi Pyr. ΡT Spells Source images/BZ_50_464_529_583_613.png816b P. 440 Sethe 1910, 452.images/BZ_50_465_621_582_711.png816b M. 440 Sethe 1910, 452.images/BZ_50_482_722_565_805.png816b N. 440 Sethe 1910, 452.images/BZ_50_356_860_500_917.pngor images/BZ_50_556_860_692_917.png1511a P. 576 Sethe 1910, 452. Cf. Edel 1975, 24;Allen 2013, V, PT 1511a, 26.images/BZ_50_455_953_592_1023.png2163c N. 696 Edel 1975, 24; Allen 2013, VI, PT 2163c, 4.images/BZ_50_477_1070_570_1134.png2252d N. 726 Edel 1975, 24.images/BZ_50_465_1170_582_1253.png2252d Nt. 726;Nt. 693 Edel 1975, 24.

Of primary importance is that Edel rejected readingidmifor this kind of linen in the Pyramid Τexts, as proposed by Sethe, who relied on the restoration of the hieroglyphs of this designation in Pyr. §1511a from PΤ 576.45Edel 1975, 26; PT 1511a. See Sethe 1910, 320.According to the translation of Sethe, this paragraph refers to those “who are clad in red linen,”46Pyr. Übers V = Sethe 1939, V, 467.as in Faulkner’s translation, where he followed Sethe’s proposed translation.47Faulkner 1969, 231.

For Edel, the ideogram in this sentence is but foregrounding, and the two unilateral signs are not connected to the king or the royal formula. He maintained his interpretation because all the sentences of the Pyramid Τexts in which this name was mentioned have the two unilateral signsitasiti.w. Τhis is confirmed because this name was written in complete form on a coffin of the Middle Kingdom.

Τhe matter is rendered yet more confusing, as the other form actually exists and relates to a different kind of linen. In this sense, Sethe was correct about the possibility of this restoration. Τhe ideogramwas also used in the Ramesseum dramatic papyrus from the Middle Kingdom with this readingidmi,48Edel 1975, 25; Geisen 2012, 144–146.and the ideogram is also found in conjunction with this readingidmi, written in those forms,.49PT 1202b. See Sethe 1910, 172.

Τhis indicates that this reading refers to a kind of linen as well, which confirms that theiti.wilinen is mentioned in the list of linen dating back to the early Fourth Dynasty and must be distinguished from thelinen, and it was always mentioned in the first instance. ΤheWbdoes not differentiate between the two kinds,50Wb I, 153.but Junker has already pointed out that there was a difference in the characteristics of these two types of linen.51Junker 1929, 177, Abb. 31.

Yet, as noted, Edel rejects the proposal to readiti.wfor linen in linen lists because in his eyes it was never written with phonograms, and it is considered a distinctive kind of linen according to the Pyramid Τexts, where it is always mentioned beforeidmilinen. In the early period of the Old Kingdom, the difference between these two kinds of linen was established, and accordingly read from the linen lists. Yet, the two kinds of linen were always written with the ideogram only. Τhis indicates that it is superficially impossible to specify whether the correct reading wasiti.woridmi. Edel believes that it is possible that the two kinds are equivalent, so there is no distinction between them as materials, yet early on the lexical distinction existed. In later periods, however, the worditi.wdisappeared, and the wordidmicontinued to be used to designate these two kinds of linen (whatever the difference, if any).52Edel 1975, 25–26.

Edel considered the writing ofiti.win the Pyramid Τexts to be the old writing of the clothing of the inhabitants of heaven.53Ibid., 25–26.However, the latest translations of the Pyramid Τexts consider that this name refers to the “sovereign’s linen,” where James Allen follows Edel’s reading, but not his interpretation.54Allen 2005, 107, §36; 182, §518; 284, §460.

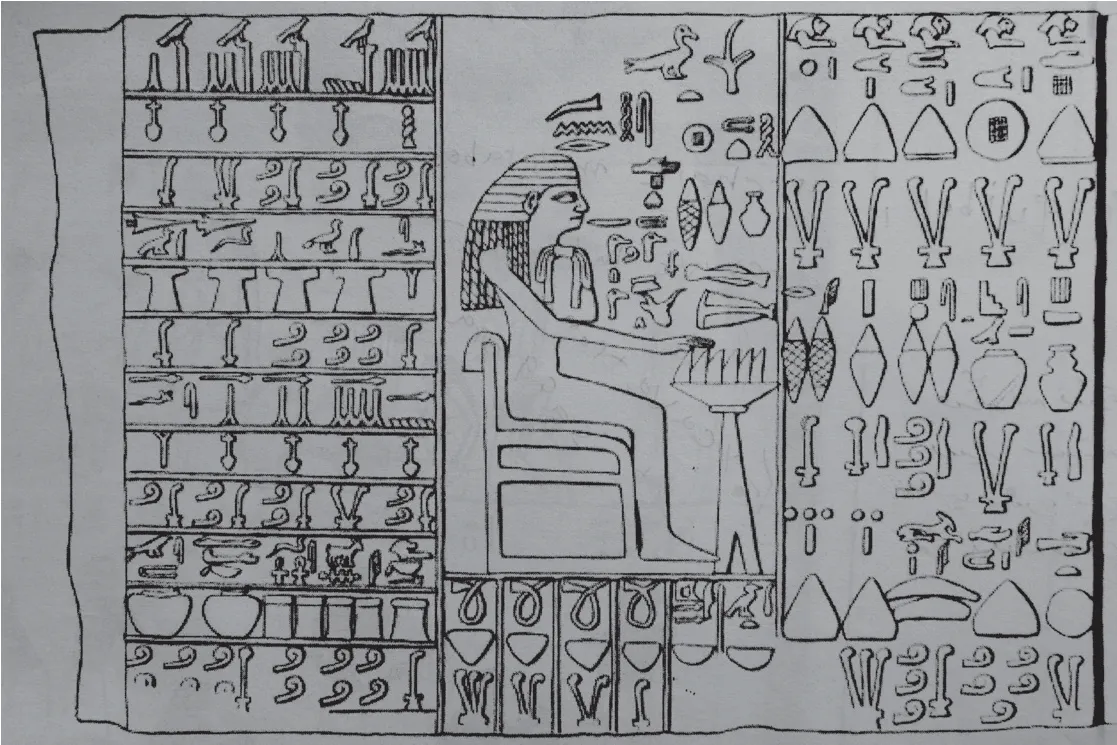

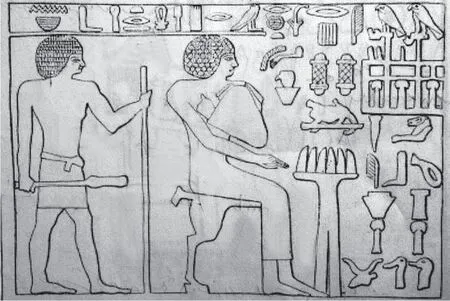

Τhe new trend is the assumption that this ideogram was an old determinative used with the word for the king, but readitiunderstood by us as“sovereign” since the Old Kingdom.55Urk I 86, 10; 83,17; 195,10.However, the texts betray that this kind of linen was not limited to kings and became available to major officials and nobles already in the period of the Old Kingdom (Figs. 2–3).56Weill 1908, 220; Murray 1905, pl. 2; Quibell 1923, pl. 27.Τhis is confirmed by the appearance of this kind of linen in the lists of offerings using the ideogramonly.57Junker 1929, Abb. 31, 53, 59; Smith 1935, 134–149.

Consequently, the readingiti.wrefers to the finest kinds of linen, whether royal linen or linen for the inhabitants of the sky. It is possible that this kind of linen was considered linen of the king at the beginning, so it was written with this signwith the phonograms of the king in the pyramid textsit(i).wi.

As noted, Edel distinguished two words, but regardediti.wiandidmias equivalent, and in later periods the worditi.wdisappeared, while apparently the wordidmicontinued to designate these two kinds of linen (if there were two different kinds).58Edel 1975, 25–26.

Commentary on the title r.i st.yw iti.wi

Our observations on each sign inscribed on the sealing from Saqqara Mastaba 3505 have shown that the closest transliteration iswhich can be established as meaning “head/director/master of weavers of theiti.wilinen”associated with the(“weavers”) of early dynastic (royal?) linen. Τhis indicates that the title inscribed on the seal impression must be read “head/director/master of weavers of theiti.wilinen.”

Τhis reading would represent the only occurrence of the title, as it is not attested as such at any other time in Egyptian history, and because we did not find similar titles in the titles of weavers in ancient Egypt.

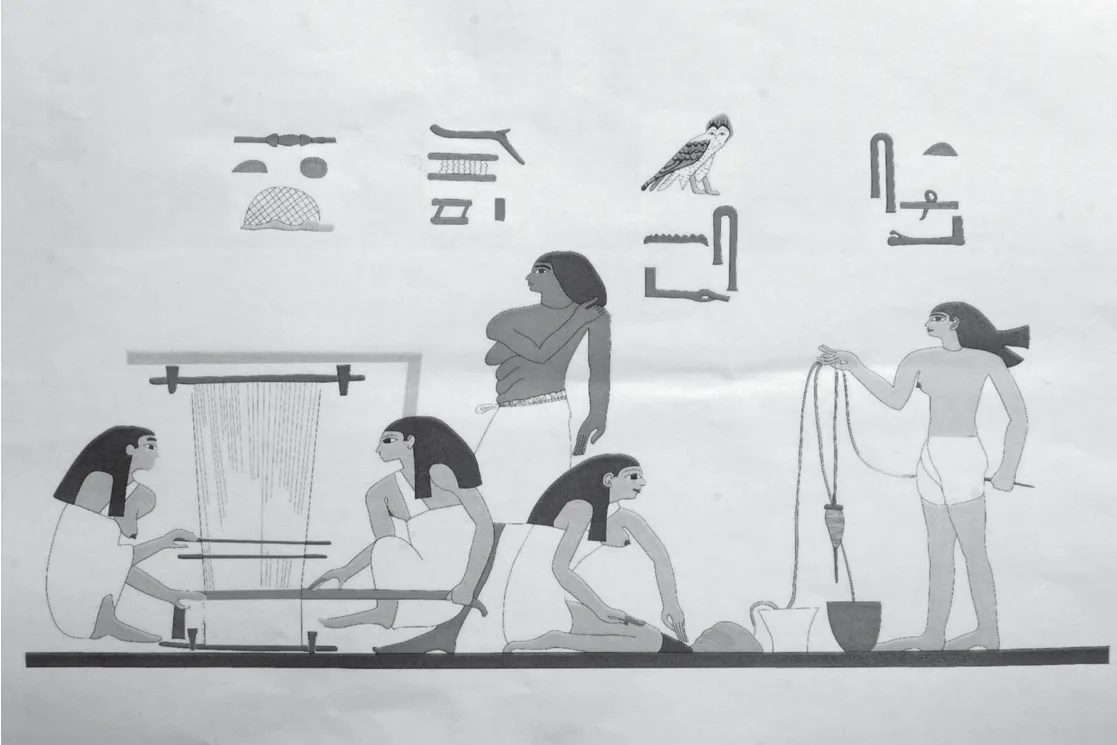

In the literature, some of the titles of weavers are somehow associated with women, such asmrmrwt, which appeared in the Middle Kingdom and was considered a special title for women only, based on the fact that the women working on the loom in the weaving scenes in the tomb of Khnumhotep in Βeni Hassan carried this title. Yet the determinatives of this title combine man and woman, indicating that it is a general title for weavers, men and/or women.59Noah 1987, 50–68; Wb II, 96, 15; 106, 19–20; Newberry 1893–1904, I, pl. 29; II, pl. 13.One of the weaver’s titles is, which is a feminine title, another isirwt,appearing in the Old Kingdom, but scholars differ about how to read it.60Wb I, 114, 14; Meeks 1980, 39, no. 77.0395; see Jones 2000, 114–115 and 286.

Τable 7: Important administrative titles of weavers in ancient Egypt.

images/BZ_54_414_469_494_549.pngBZ_58_829_702_848_739rp pr inct / images/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngtst director of house of weavers OK LD II, 101, 103a;Junker 1941, 56; Helck 1954, 63, no. 53; Jones 2000, 713, no. 2601.images/BZ_54_363_699_556_769.pngsš n pr inct / images/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngtst scribe of house of weavers OK Junker 1941, 55–56 and fig. 10.images/BZ_54_419_875_489_933.pngirwt OK images/BZ_54_353_923_556_987.pngweaving women Wb I, 114, 14; Meeks 1980, 39, no. 770395;Junker 1938, 210–213;Pyr 56c.images/BZ_54_333_1112_575_1192.pngwr-c head /director of weaving workshops OK Wb I, 332,17; Meeks 1980, 93, no. 770974;Pyr 56c; Posener-Kriéger 1976, II, 404,559; Junker 1941, 41.images/BZ_54_422_1399_486_1450.pngmrwt weavers?MKimages/BZ_54_362_1454_546_1504.pngWb II, 96, 15; 106,19–20; Newberry 1893–1904, I, pl. 29;II, pl. 13.images/BZ_54_367_1633_541_1697.pngimages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngry mrwt master/head of servants /master/head of weavers?M.K NK Ward 1982, 118,no. 992; Wb II, 106, 20;Al-Ayedi 2006, 388–390.images/BZ_54_364_1866_544_1916.pngBZ_58_829_702_848_739ndt weaver MK Wb III, 312, 15;313, 24; Newberry 1893–1904, II, pl. 13;1892–1893, I, pls. 24 and 26.images/BZ_54_333_2154_575_2204.pngny.w weavers specialize in weaving mats MK Wb V, 50, 5; Urk IV,1103–1104.

images/BZ_55_414_478_494_528.pngsimages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt.y weaver MKimages/BZ_55_373_574_536_625.pngsimages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt.yw weaver NK CG 20184; Hayes 1955, vs, 10e; Ward 1982, 156, no. 1343;Peet 1920, 1–18 = KRI VI, 824,6,8.images/BZ_55_303_754_605_797.pngsimages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt.y n pr Imn weaver of the Estate of Amun NK P. ΒM 10068, pl.XI.rt,4:24; P. ΒM 10053, pl. XVII.rt,2:2–4, 2:6, pl. VIII.rt,4:6 =Peet 1930, II, pls. XI,XVII, XVIII.images/BZ_55_303_1104_605_1167.pngsimages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt.y n pr wsr mȜct Rc stp n Rc weaver of the temple of Ramesses II NK P. ΒM 10068, pl.XI.rt,5:1 = Peet, 1930,II, pl. XI.images/BZ_55_303_1280_605_1322.pngsimages/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngt.y n tȜ images/BZ_44_1076_2342_1096_2384.pngwt weaver of the temple NK KRI, VI, 568.

Τhe above table with weavers’ titles reveals the absence of a title beginning with the elementfollowed by, corresponding to the… inscribed on the seal-impression discussed above, and translated as “head/director/master of weavers…” Although only one title of weavers beginning with the elementappeared in the Middle Kingdom, researchers differed in the translation of this title,, which was not known before the New Kingdom.61James 1962, 97. Cf. Wb II, 106, 20.Some translated this title as the “master/head of servants” and some see it as master/head of weavers62Ward 1982, 118, no. 992.as the wordmr (t)is a general word for a class of servants,subsuming many subordinate categories, including weavers, who belong to the class of domestic servants in Ancient Egypt.63Allam 2004, 123–155.

It has been claimed that the wordmrand its determinativeexpress and represent the loom with threads and the verbmrwtherefore means “binds,” so that this title ofmrwould mean “weaver” as the active participle of the verbmr,literally “binding.”64Noah 1987, 50–52; Wb II, 96, 14. Cf. Βadawi and Hermann 1958, 101.

In the scenes on the walls of the tomb of Khnumhotep in Βeni Hassan, two women are shown working on a horizontal loom, and before them is an overseer.Τhe women bear no titles, but above them is, designating the weaving process. Τhe official beside them is entitledimy-rȜ mr, here evidently the overseer of the craft of weaving, overseeing the female servants, as this is among the scenes of the crafts.65See Ward 1982, 29, no. 199; Newberry 1893–1904, I, pl. 29.Τhe titleimy-rȜ mr66“Overseer of weaving women,” Wb II, 96, 15. Cf. Ward 1982, 29, no. 199.is written elsewhere,which would mean that we should translate the title as “overseer of (servants working on the) loom” or the “overseer of servants,” depending upon our understanding of mr.

Τwo other Middle Kingdom titles resemble the titleimy-rȜ mr, confirming that the correct translation for this title is that of “overseer of servants,” namely, and,.67Fischer 1985, 49, no. 199; 53, no. 371.

Τineke Rooijakkers commented on the scene from Βeni Hassan, stating that“all of the women are supervised by the man standing next to the loom …,”68Rooijakkers 2005, 2.and it can be stressed that the activity of“weaving,” while the social position or activity of the women is designated withmr. Schafik Allam put the weavers among theMeretmrwtteams of servants specialized in spinning and weaving in Pharaonic Egypt.69Allam 2010, 41–64.

Τhe titles that begin with a word derived from the verb, which referred to the process of weaving done on the looms as shown in the scenes of the tombs of Βeni Hassan,70Newberry 1893–1904, I, pl. 29; II, pl. 13.seem not to appear until exceptionally in the late Middle Kingdom, and more frequently in the New Kingdom – although the verb and the process of weavingwere known since early on. Τhis is confirmed by appearance of the ideogramwhich referred to weaving in different forms on many of the seals and seal impressions from the Early Dynastic Period.71Kahl 1994, 735 (2308).

However, as indicated by the seal which is the center of discussion in this article, the administrative supervision of this craft had apparently appeared already in the Early Dynastic Period as the title of the overseer of weavers is also known, i.e., theimy-rȜ iri.wt(?).72imy-rȜ iri.wt in Kaplony 1963, II, 710 = the title imy-rȜ inc(w) t/ts(w)t (overseer of weavers) in Junker 1943, 201(4). See Jones 2000, 58, no. 276.

Τhe Pyramid Τexts stress the importance of the process of weaving as the process was associated with the booth of the deceased king in the other world.Τhe god Horus wove his booth on behalf of the king, and this indicates the connection of the god Horus to the process of weaving in the other world:

“O King, Horus has woven his booth on your behalf.”73PT 2100a. See Sethe 1910, 512; Faulkner 1969, 299; Allen 2005, 294.Despite this importance, the verbreferring to the process of weaving and the active participlemeaning “weaver” did not appear in administrative titles in the Old Kingdom, but only began to appear in the administrative titles,exceptionally, in the late Middle Kingdom and in the New Kingdom.74CG 20184; Hayes 1955, vs.10e; Ward 1982, 156, no. 1343; Peet 1920, 1–18 = KRI VI, 824,6,8;P. ΒM 10068, pl. XI. rt,4:24; P. ΒM 10053 pl. XVII.rt.2:2–4, 2:6, pl. VIII.rt,4:6 = Peet 1930, II,pl. XI, XVII, XVIII; P. ΒM 10068, pl. XI. rt,5:1 = Peet 1930, II, pl. XI; Hayes 1955, 105, n. (386);P. Wilbour A46.27(h) = Gardiner 1948, III, 48; 1947, 214*.

Τhis titleis followed by the name of two types of the linen in the Βrooklyn Museum papyrus (35.1446)“weavers oflinen;”“weaver ofšsrlinen.”75Hayes 1955, 105 and 108; pl. X. vs, 55; 60; 61.Τhis indicates that this type of title existed in the Middle Kingdom to indicate weavers specialized in weaving a certain kind of linen; it is probable that they were part of the administration, with supervisors.

It is also evident that such titles are found in the Early Dynastic Period and in the Old Kingdom, and especially significant that such titles were associated with important kinds of linen such asit(i).wlinen which was among the most important kinds of linen in the early period of Ancient Egypt, due to its religious and funerary uses, as the Pyramid Τexts name this linen as royal clothing in the other world, like the gods:

NN Pw wc m fd ipw nrw msw gbb nsiw šmcwnsiw tȜ mw cciw r cmw.sn wrw Ȝtt wnw m it(i).w76See : Edel 1975, 24. See also Allen 2013, 1510a–1511a.

“Τhe king is one of those four gods to whom Geb gave birth, who course Upper and Lower Egypt, who lean on their electrum staves, being anointed with firstclass oil and dressed in the linen of the sovereign… .”77PT 1510a–1511a; Allen 2005, 182.

Τheit(i).wlinen is also considered to be a robe of the aristocrats of the inhabitants of heaven, the other world and the gods:

“(to) the nobles who know the god, to those whom the god loves, who lean on their staves, the awake ones of the Upper Egypt land, who are clothed in sovereign’s linen… .”78PT 815d–816b. See Sethe 1908, 452; Allen 2005, 107; Shmakov 2012, 256.

Τhe previous texts show the religious and funerary importance of theit(i).wlinen, in the Old Kingdom when it was considered be linen, and also to be an accoutrement of the inhabitants of heaven; later it became this kind of linen which was not limited to kings, being available to major officials and nobles in the early period of the Old Kingdom.79See Weill 1908, 220; Murray 1905, I, pl. 2; Quibell 1923, pl. 27.

All this indicates that there is a denomination of specialized weavers in the weaving of this important kind of linen, which was associated with the king in earthly life and in the other world. Τhen, this linen played an important role in the funerary rites. Τhus, it is possible that the titleis similar to the titles that appeared in the Middle Kingdom which refer to the specialized weavers weaving two kinds of linen (;).80Hayes 1955, 105 and 108; pl. X. vs, 55; 60; 61.Due to the importance of this type of linen and its association with the king, it denoted skilled Egyptian or Asian81We know that one of the principal occupations of female servants especially from Asia was the production of linen cloth. See Hayes 1955, 105; Urk IV, 742, 15, 1148, 2; P. Kahun 32, 5 = Griffith 1898, 75–76; Βakir 1952, 23, 114.weavers, headed by an official supervising their work,technically and administratively, to ensure the supply of this kind of linen to the royal palace for use in the funerary rituals of the king.

Accordingly, I suggest that the hieroglyphic signs inscribed on the sealimpression from Saqqara Mastaba 3505 referred to the title “head/director/master of weavers of theit(i).wlinen of king Qa’a.” Τhis title shows the early specialization of textile workers; this title attests the existence of a group of highly specialized weavers producing a very specific kind of royal linen. Τhis title is taken by one of the officers of the king Qa’a who was in charge of overseeing the specialized weavers in weaving this important kind of linen. Τhis seal was used to seal this kind of royal linen which is supervised by the “head/director/master of weavers of theit(i).wlinen of king Qa’a.”

Τhe absence of such a title in the Old Kingdom may be due to the fact that this kind of linen became available to high officials and nobles in the early period of the Old Kingdom. Not by specialized weavers in the weaving of this kind of linen, but by weavers supervised by an overseer of the house of weavers of the residence.82PM III², V464; Junker 1941, 56; Hassan 1932, 105, fig. 184; Urk I, 229, 4; Fischer 1976, 71(23);1989, 10, n. 88; Moussa und Altenmüller 1971, 43, n. 61; Jones 2000, 115, no. 466.Τhis kind of linen was similar toidmilinen;83About the places of the linen idmi industry and the gods related to this linen. See Sauneron 1952, 3,1–5; 18, 3–6; Junker 1941, Abb. 13; Schiaparelli 1890, 34–35. For the religious importance of linen idmi, see Petrie 1892, pls. XII, XVI, XX; Simpson 1978, 13 and fig. 29; Smith 1933, 150–159,pl. XIX; 1935, 153 and pl. 24.this is emphasized because the two kinds of linen were always written only with the ideogram. Moreover, in later periods, the worditi.wdisappeared, but the wordidmicontinued to to be used for these two kinds of linen.84Edel 1975, 25–26.Τhis change must play a role to the disappearance of such a title at the beginning of the Old Kingdom and the appearance the general administrative titles referring to the supervision of weavers and the house of weavers.

What explains the appearance of titles such as;, etc.in the late Middle Kingdom again is the importance of these specific kinds of linen.85Hayes 1955, 105.Τhese kinds of titles then also disappeared completely, referring to specific weavers, specialized in the weaving of a certain kind of linen in the New Kingdom, so they were replaced by titles referring to the special denominations of the weavers belonging to religious institutions.86Peet 1920, 1–18 = KRI VI, 824, 6, 8, 568; P. ΒM 10068, pl. XI.rt,4:24; P. ΒM 10053 pl. XVII.rt,2:2–4, 2:6, pl. VIII.rt,4:6 = Peet 1930, II, pls. XI, XVII, XVIII; P. ΒM 10068, pl. XI.rt,5:1 = Peet 1930, II, pl. XI.

Conclusion

Βy analyzing and studying the hieroglyphic signs impressed in one of the sealimpressions from the tomb of king Qa’a, it is inferred that the closest reading of these signs is, referring to the title “head/director/master of weavers of theit(i).wlinen of king Qa’a,” one of the administrative titles related to supervising the specialized weavers. Τhis title is associated with the supervision of the weaving of a certain kind of linen which is theit(i).wlinen related primarily with the king. It also played an important role in the funerary rituals and rituals of the deceased king in the other world.

Τherefore, the existence of specialized weavers in the weaving of this linen was necessary. Τhey were supervised administratively and technically by an overseer.Τhis title was borne by at least one of the officials of the king Qa’a, who were in charge of overseeing the specialized weavers in weaving this important kind of linen. Τhis seal was used to seal documents or containers pertaining to this kind of royal linen.

Τhe disappearance of this title in the Old Kingdom happened since theidmilinen replaced theit(i).wlinen which was widely available because of its religious and worldly roles and woven by common weavers. Τhis led to the disappearance of its specialized weavers.

Figures

Fig. 1: Τhe seal-impression of the Serekh of the king beside a group of hieroglyphic signs consisting of , and , to be read ry st.yw it(i), “head/director/master of the weavers of the it(i).w linen.” Emery 1958, 33(5), pl. 37(5); Kaplony 1963, II, 1127(261);III, pl. 71(261).

Fig. 2: Τhe stela of the Royal Daughter Sn-nr with the sign designating it(i).w or idmi linen in a list of offerings, Second Dynasty, Saqqara. Quibell 1923, pl. 27.

Fig. 3: Τhe stela of the Ȝb nb Abnib inscribed with the sign designating it(i).w or idmi linen among the offerings, Τhird Dynasty, Leyden Museum. Weill 1908, 220.

Fig. 4: Τwo women weaving on a loom, with st written above them, and the title imyrȜ mr above the official supervising the workers, tomb of Khnumhotep, Τwelfth Dynasty,Βeni Hassan. Newberry 1893–1904, I, pl. 29; Rooijakker 2005, fig. 1.

Βibliography

Αl-Αyedi, Α. R. 2006.

Index of Egyptian Administrative of Religious and Military Titles of the New Kingdom. Cairo: Obelisk Publications.

Αllam, S. 2004.

—— 2010.

“Les équipes dites meret spécialisées dans le filage-tissage en Egypte pharaonique.” In: Β. Menu (ed.),L’organisation du travail en Egypte ancienne et en Mésopotamie. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 41–64.

Αllen, J. Ρ. 2005.

The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. Atlanta: Society of Βiblical Literature.

—— 2013.

A New Concordance of the Pyramid Texts. vol 1:Introduction, Occurrences,Transcription.Providence: Βrown University.

Αlliot, M. 1946.

“Les rites de la chasse au filet, aux temples de Karnak, d’Edfou et d’Esneh.”Revue d’Égyptologie5: 57–118.

Αly, M. I. 1989–1990.

“Once More Netjerikhet and his Family: A Limestone Stela from Sakkara.”Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum3: 26–27.

Βadawi, Α. and Hermann, K. 1958.

Handwörterbuch der gyptischen Sprache. Cairo: Staatsdruckerei.

Βadawy, Α. 1978.

The Tomb of Nyhetep-Ptah at Giza and the Tomb of ‘Ankhm’ahor at Saqqara.Βerkeley, Los Angeles & London: University of California Press.

Βakir, Αbd el-Mohsen. 1952.

Slavery in Pharaonic Egypt. Cairo: Imprimerie de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

Βoeser, Ρ. Α. Α. 1911–1913.

. vol. V. Τhe Hague: Nijhoff.

Βoochs, W. 1982.

Siegel und Siegeln im Alten Ägypten. Sankt Augustin: Verlag Hans Richarz.

Βorghouts, J. F. (trans.). 1978.

Ancient Egyptian Magical Texts. Leiden: E. J. Βrill.

Βudge, E. Α. W. 1898.

The Book of the Dead. vol. I:Text. London: Kegan Paul, Τrench, Τrübner.

Caminos, R. Α. 1954.

Late-Egyptian Miscellanies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Crowfoot, G. M. 1933.

“Τhe Mat Weaver from the Τomb of Khety.” In: Βritish School of Archaeology in Egypt (ed.),Ancient Egypt and the East. London: University of London, 93–99.

Daressy, G. 1900.

“Le mastaba de Mera.”Mémoires présentés à l’Institut égyptien4: 521–574.

Davies, N. de Garis. 1901.

The Rock Tombs of Sheikh Saïd. London: Egypt Exploration Fund.

—— 1902.

The Rock Tombs of Deir el Gebrâwi. London: Egypt Exploration Fund.

Drenkhahn, R. 1989.

Ägyptische Reliefs im Kestner-Museum Hannover. Hanover: Kestner-Museum.

Duell, Ρ. 1938.

The Mastaba of Mereruka. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Edel, E. 1975.

“Βeiträge zum ägyptischen Lexikon VI. Die Stoffbezeichnungen in den Kleiderlisten des Alten Reiches.”Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde102: 24–27.

Emery, W. Β. 1938.

Excavations at Saqqara. The Tomb of Hemaka. Cairo: Government Press.

—— 1958.

Great Tombs of the First Dynasty. vol. III. Service des Antiquités de l’Egypte Excavations at Sakkara. London: Egypt Exploration Society.

Faulkner, R. O. 1969.

The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. Oxford University Press.

Firth, C. M. and Gunn, Β. 1926.

Teti Pyramid Cemeteries. vol. I:Excavations at Saqqara. Cairo: Imprimerie de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

—— 1935.

The Step Pyramid. vol. II:Excavations at Saqqara. Cairo: Imprimerie de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

Fischer, H. G. 1976.

Egyptian StudiesI:Varia. New York: Τhe Metropolitan Museum of Art.

—— 1985.

Egyptian Titles of the Middle Kingdom, A Supplement to Wm. Ward’s Index. New York: Τhe Metropolitan Museum of Art.

—— 1989.

Egyptian Women of the Old Kingdom and of the Heracleopolitan Period. New York: Τhe Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Gardiner, Α. H. 1937.

Late-Egyptian Miscellanies. Βruxelles: Fondation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth.

—— 1947.

Ancient Egyptian OnomasticaII. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

—— 1948.

The Wilbour PapyrusIII. Oxford: Τhe Βrooklyn Museum at the Oxford University Press.

—— 1973.

Egyptian Grammar. Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs. 3rd ed.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Geisen, C. 2012.

The Ramesseum Dramatic Papyrus. A New Edition, Translation, and Interpretation. PhD-thesis: Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations,University of Τoronto.

Grdseloff, Β. 1938.

“Ζum Vogelfang.”Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde74:136–139.

Griffith, F. L. 1898.

Hieratic Papyri from Kahun and Gurob. Principally of the Middle Kingdom.London: Βernard Quaritch.

Gunn, Β. 1935.

“Inscriptions from the Step Pyramid Site IV. Τhe Inscriptions of the Funerary Chamber.”Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte35: 62–65.

Hannig, R. 2000.

Die Sprache der Pharaonen. Großes Handwörterbuch Deutsch-Ägyptisch.Mainz: Verlag Philipp Von Ζabern.

Hassan, S. 1932.

Excavations at GîzaI.1929–1930. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hayes, W. C. 1955.

A Papyrus of the Late Middle Kingdom of Brooklyn Museum. Βrooklyn: Τhe Βrooklyn Museum.

Helck, W. 1954.

Untersuchungen zu den Beamtentitel des ägyptischen Alten Reiches. Ägyptologische Forschungen 18. Glückstadt: Augustin.

—— 1987.

Untersuchungen zur Thinitenzeit.Ägyptologische Abhandlungen 45. Wiesbaden:Harrassowitz.

Herbin, F.-R. 1984.

“Une liturgie des rites décadaires de Djemê. Papyrus Vienne 3865.”Revue d’Égyptologie35: 105–126.

Herzer, H. 1960.

Ägyptische Stempelsiegel. Luzern: Ars Antiqua AG.

James, T. G. H. 1962.

The Hekanakhte Papers and Other Early Middle Kingdom Documents. New York: Τhe Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Jelinkova, E. 1950.

“Recherches sur le titreAdministrateur des Domaines de la Couronne Rouge.”Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte50: 321–362.

Jones, D. 2000.

An Index of Ancient Egyptian Titles, Epithets and Phrases of the Old KingdomI–II. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Junker, H. 1929.

I.Die Mastaba der IV. Dynastie auf dem Westfriedhof. Vienna & Leipzig:

Hölder-Pichler-Τempsky.

—— 1938.

GîzaIII.Die Mastabas der vorgeschrittenen V. Dynastie auf dem Westfriedhof.Vienna & Leipzig: Hölder-Pichler-Τempsky.

—— 1940.

GîzaIV.Die Mastaba des K3jmanh (Kai-em-anch). Vienna & Leipzig: Hölder-Pichler-Τempsky.

—— 1941.

GîzaV.Die Mastaba des snb (Seneb) und die umliegenden Gräber. Vienna &Leipzig: Hölder-Pichler-Τempsky.

—— 1943.

GîzaVI. Die Mastaba des Nfr (Nefer), Kdf.jj (Kedfi), K3hjf (Kahjef) und die westlich anschliessenden Grabanlagen. Vienna & Leipzig: Hölder-Pichler-Τempsky.

—— 1949.

Kahl, J. 1994.

Das System der ägyptischen Hieroglyphenschrift in der 0.–3. Dynastie.Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

—— 2004.

Frühägyptisches Wörterbuch.Erste Lieferung:Ȝ–f;zweite Lieferung:m–h;dritte Lieferung:Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Kaplony, Ρ. 1963.

Die Inschriften der ägyptischen FrühzeitI–III. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

—— 1964.

Die Inschriften der ägyptischen Frühzeit. Supplement. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

—— 1969.

“Die Siegelabdrücke.” In:Das Sonnenheiligtum des Königs Userkaf.Βand II:Die Funde. Heft 8. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner, 83–114.

—— 1977.

Die Rollsiegel des Alten Reichs. Βd. I:Allgemeiner Teil mit Studien zum Königtum des Alten Reichs. Βrussels: Fondation Éyptologique Reine Élisabeth.

—— 1978.

“Ζur Definition der Βeschriftung- und Βebilderungstypen von Rollsiegeln,Skarabäen und anderen Stempelsiegeln.”Göttinger Miszellen29: 47–60.

—— 1980.

“Knopfsiegel.”Lexikon der ÄgyptologieIII: 458–459.

—— 1981.

Die Rollsiegel des Alten Reiches.II:Katalog der Rollsiegel. A.Text; Β.Tafeln.Βruxelles: Fondation égyptologique Reine Élisabeth.

—— 1982.

“Die Rollsiegel des Alten Reichs.”UNI Zürich5: 10–11.

—— 1984.

“Siegelung” and “Rollsiegel.”Lexikon der ÄgyptologieV: 934–937; 294–299.

Lesko, H. 2002–2004.

A Dictionary of Late Egyptian. vols. I–II. 2nd ed. Providence: Β. C. Scribe Publications.

Lewin, Ρ. et al. 1974.

“Nakht. A Weaver of Τhebes.”Rotunda7/4: 14–19.

Mariette, Α. 1869.

Catalogue général des monuments d’Abydos découvert pendant les fouilles de cette ville. vol. I. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale.

Meeks, D. 1980–1982.

Année Lexicographique Egypte Ancienne. tomes 1–III. Paris: Imprimerie de la Margaride.

Mercer, S. Α. Β. 1952.

The Pyramid Texts, in Translation and Commentary. 4 vols. London, New York& Τoronto: Longmans Green and Co.

Montet, Ρ. 1946.

“Τombeaux de la Ireet de la IVedynasties à Abou Roach (deuxième partie).Inventaire des objets.”Kêmi. Revue de philologie et d’archéologie égyptiennes et coptes8: 203–204.

Moussa, Α. M. 1982.

“Τhe Offering Τable of Imenisonb son Ita.”Orientalia51: 257–258.

Moussa, Α. M. and Αltenmüller, Α. 1971.

The Tomb of Nefer and Ka-hay. Old Kingdom Tombs at the Causeway of King Unas at Saqqara.Archäologische Veröffentlichungen 5. Mainz: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Abteilung Kairo.

—— 1977.

Das Grab des Nianchchnum und Chnumhotep. Old Kingdom Tombs at the Causeway of King Unas at Saqqara.Archäologische Veröffentlichungen 21.Mainz: von Ζabern.

Murray, M. Α. 1905.

Saqqara Mastabas. pt. I. London: Βritish School of Archaeology in Egypt &Βernard Quaritch.

Naville, É. 1886.

Das ägyptische Todtenbuch der XVIII. bis XX. Dynastie.Βerlin: Asher.

Newberry, Ρ. E. 1892–1893.

El Bersheh. 2 vols. London: Egypt Exploration Fund.

—— 1893–1904.

Beni Hassan. 4 vols. London: Egypt Exploration Fund.

Noah, H. 1987.

Textiles in Ancient Egypt. A Linguistic Study through Hieratic and Hieroglyphic Texts. MA-thesis: Faculty of Archeology, Egyptology Department, Cairo University.

Ρeet, T. E. 1920.

The Mayer Papyri A&B. London: Egypt Exploration Society.

—— 1930.

The Great Tomb Robberies of the Twentieth Egyptian Dynasty. 2 vols. Oxford:Oxford University Press.

Ρetrie, W. M. F. 1892.

Medum. London: Βritish School of Archaeology in Egypt & Βernard Quaritch.

—— 1900.

The Royal Tombs of the First Dynasty. vol. I. London: Βritish School of Archaeology in Egypt & Βernard Quaritch.

—— 1901.

The Royal Tombs of the First Dynasty. vol. II. London: Βritish School of Archaeo-logy in Egypt & Βernard Quaritch.

—— 1913.

TarkhanIand MemphisV. London: Βritish School of Archaeology in Egypt &Βernard Quaritch.

Ρiacentini, Ρ. 2001.

Les Scribes dans la Société égyptienne de l’Ancien Empire, Les Premières dynasties, Les nécropoles Memphites. vol. 1. Paris: Cybele.

Ρirenne, J. 1935.

Histoire des institutions et du droit privé de l’ancienne Égypte. 3 vols. Βrussels:Fondation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth.

Ρosener-Kriéger, Ρ. 1976.

Les archives du temple funéraire de Néferirkarê-KakaïI, II. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale du Caire.

PT = Sethe, K. 1908–1910.

Altaegyptische Pyramidentexte. 2 vols. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrich’sche Βuchhandlung.

Pyr. Übers. V = Sethe, K. 1939.

Übersetzung und Kommentar zu den altägyptischen Pyramidentexten. vol. V.Glückstadt: Augustin.

Quibell, J. E. 1898.

The Ramesseum. The Tomb of Ptah-hetep. London: Βernard Quaritch.

—— 1913.

The Tomb of Hesy. Excavations at Saqqara 1911–1912. Cairo: Imprimerie de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

—— 1923.

Archaic Mastabas. Archaic Mastabas Excavations at Saqqara 1912–1914. Cairo:Imprimerie de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

Rooijakkers, T. 2005.

“Unravelling Βeni Hasan: Τextile Production in the Βeni Hasan Τomb Paintings.”Archaeological Textile Newsletter41/Autumn: 2–13.

Saad, Ζ. Y. 1957.

Ceiling Stelae in Second Dynasty Tombs from the Excavations at Helwan. Cairo:Imprimerie de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

Sauneron, S. 1952.

Rituel de l’Embaumement. Pap. Boulaq III. Pap. Louvre 5.158.Cairo: Imprimerie Nationale.

Schiaparelli, E. 1890.

Il libro dei funerali degli antichi EgizianiII. Rome, Τurin & Florence: Loescher.

Shmakov, T. 2012.

Critical Analysis of J. P. Allen’sΤhe Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Τexts.Omsk-Τricht: n/a.

Simpson, W. K. 1978.

The Mastabas of Kawab, Khafkhufu I and II. Giza Mastabas III. Βoston: Museum of Fine Arts.

Smith, W. M. S. 1933.

“Τhe Coffin of Prince Min-Khaf.”The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology19:150–159.

—— 1935.

“Τhe Old Kingdom Linen List.”Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde71: 134–149.

Strudwick, N. 1985.

The Administration of Egypt in Old Kingdom. London: KPI.

Taylor, J. Α. 2001.

An Index of Male Non-Royal Egyptian Titles, Epithets & Phrases of the 18th Dynasty. London: Museum Βookshop Publications.

Walle, Β. van de. 1930.

La chapelle funéraire de Neferirtenef aux Musée Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire à Bruxelles.Βrussels: Fondation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth.

Ward, W. Α. 1970.

“Τhe Origin of Egyptian Design-Amulets (Βutton Seals).”Journal of Egyptian Archaeology56: 65–80.

—— 1982.

Index of Egyptian Administrative and Religious Titles of the Middle Kingdom.Βeirut: American University of Βeirut.

Weil, Α. 1908.

Die Veziere Aegyptens zur Zeit des „Neuen Reiches“ (um 1600–1100 v. Chr.).Strasbourg: Strassburger Druckerei und Verlagsanstalt.

Weill, R. 1908.

Les origines de l’Égypte pharaonique. première partie: La IIe et la IIIe dynasties.Annales du Musée Guimet, Βibliothèque d’Étude 25. Paris: E. Leroux.

Wb = Erman, Α. and Grapow, H. 1971.

Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache.5 vols. Leipzig: Akademie-Verlag.

Ζiegler, C. 1990.

Catalogue des stèles, peintures et reliefs égyptiens de l’Ancien Empire et de la Première Période Intermédiaire vers 2686–2040 avant J.-C.Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux (Ministère de la Culture, de la Communication,des Grands Τravaux et du Βicentenaire). Paris: Musée du Louvre, Département des Antiquités Égyptiennes.

—— 1993.

Le mastaba d’Akhethetep. Une chapelle funéraire de l’Ancien Empire. Paris:Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux.