THE COLLAPSE OF EARLY MESOPOTAMIAN EMPIRES –A HOMEMADE DISASTER?1

2021-02-24SebastianFink

Sebastian Fink

University of Innsbruck

If we survey the fall of Mesopotamian empires from the beginning of written sources to the end of the Neo-Babylonian Empire we find one astonishing similarity: the warlike people that finally destroyed these empires came from the East. A number of factors, not at least geography, might explain this, but here I want to focus on the effect the Mesopotamian empires had on the bordering regions themselves and discuss the possibility that the constitution of these organized political actors pushing back against the empire was a result of Mesopotamian imperial politics themselves determined by a poor evaluation of the empire’s ability to exercise direct control of areas where military actions took place. The aim of this paper is to build on earlier work and investigate the fall of the empires of Akkad and Ur III under a systemic perspective, in order to understand which factors might have caused the decline and fall of these empires that were not merely accidental. Many reasons have been suggested for the fall of Mesopotamian empires, like climatic change (Kinnier-Wilson 2005), salinization of the soil (Powell 1985), or the arrival of new peoples. Here, I want to focus on the question of whether this “arrival of new people” may be better described as the establishment of opposing political forces. They are often described as coming out of nowhere, but I would like to suggest that this was the result of an ethnogenesis or secondary state formation at the border of the empire.

The making of Mesopotamia as an imperial core

On first sight, southern Mesopotamia does not seem to be a fitting place for the first cities to emerge, as without irrigation, agriculture is only possible in the limited fertile areas, usually along the Euphrates river, and precisely these areas are those threatened by recurring flooding, which occurs regularly after seedtime. Many theories have been put forward to explain why this emergence of urbanized and complex societies happened in Mesopotamia and resulted in the establishment of Uruk, which is often regarded as the world’s first city,and the subsequent Uruk expansion.2Liverani 2006.The fact that southern Mesopotamia is situated on an alluvial plain explains why natural resources are limited. Besides agricultural products, clay, salt, and stones of minor quality, everything else needed to be imported. The softwood of the palms, poplars, and willows that grow in the salty soil of southern Mesopotamia cannot be used as construction timber for larger buildings, so we can conclude that the monumental buildings,which we recognize as a sign of urbanization, would not have been possible without imports. Therefore, this society was highly dependent on imports from foreign lands, particularly metals, stones, timber, and precious stones. Crucial to our discussion here is that among these very materials are those needed for the manufacture of weapons used in warfare, and some came from those very foreign lands which may have been the targets of the military expansion accompanying the establishment of trade routes.

Hence, we ask: how did these resource-deprived Mesopotamians manage to overcome their neighbors to the point of extracting from them, in one way or the other, the very materials that they needed in order to subjugate them? And: did this have an impact in arousing these peoples?

Some theoretical considerations

It is evident that the term “empire” is not well-defined and therefore used in a somewhat fuzzy way by historians. The only reason for me to use empire for Akkad and Ur III is to mark the contrast of the larger political entities in Mesopotamia with the smaller regional powers focused on city-states that dominated long phases of Mesopotamian history.3On the many attempts to define empire, see Rollinger, Degen and Gehler 2020.The working definition by Piotr Steinkeller seems highly suitable to me: “(E)mpire is the sustained ability to wield power over a relatively large, culturally and ethnically diversified area that was brought under one rule mainly through military conquests.”4Steinkeller 2021, 43.

By now, many different models have been proposed by researchers to make sense of the political development of Mesopotamian empires. We will start by looking at some of them. Many of these models rely on the basic assumption that sophisticated irrigation systems were a driving force behind these developments as they called for complex social organization on the one hand and fostered population growth, another important driver of social complexity on the other hand. We could say that according to these theories the establishment of complex irrigation systems was the driving force of the development of the first empires.

Model 1: Irrigation needsgrowth of population density and complex social organizationempire

This model can be described as an ecological argument to explain the development of Mesopotamian empires, based on the observation that most early states developed in river landscapes. Karl August Wittfogel (1896–1988) developed the famous theory of “oriental despotism” based on the idea that the need to construct and maintain irrigation systems shaped the character of the early states, which he designated as “hydraulic empires.”5Wittfogel 1957.While he proposed a fascinating model that seems to explain the emergence of the first states, our understanding of rule in early Mesopotamia has changed, and new data has proven that irrigation in Mesopotamia actually occurred before the rise of the first cities.6For a discussion of Wittfogel’s ideas in the light of new evidence, see Mann 2012, 94–98. A discussion of his ideas in the light of the Marxist concept of the Asiatic mode of production is given in Nippel 2020.However,Wittfogel was surely right to point out that the need to build and maintain irrigation systems led to new forms of social organization – not necessarily despotic forms we should add – and that the agricultural surplus from the irrigated fields made larger communities possible. In his theoretical framework we could argue that population size and superior organization, both a result of the hydraulic empire, are the advantages that Mesopotamia had over its neighbors.

Model 2: Lack of resources need to acquire them empire

The philosopher Arnold Gehlen (1904–1976) defined the human being as aMängelwesen(“deficient being”) and tried to explain human development by the lack of biological specialization and openness for adaption.7Gehlen 1988.According to Gehlen,human “deficits” are therefore also human strengths. Mesopotamia could be also viewed as such aMängelwesenwith regard to resources, as most of the resources for a developed urban culture8At least if we consider large palaces and temples essential for cities.simply do not exist in the alluvial land in southern Mesopotamia. Our application of Gehlen’s ideas employs a positive formulation to what is known as the “resource curse” or “paradox of plenty.” Seemingly counterintuitively, countries with plenty of natural resources generally tend to lag behind countries with less resources.9For this principle, see Ross 2014.Following Gehlen’s line of thought,southern Mesopotamia actually became “the cradle of civilization” precisely because it lacked resources rather than despite lacking resources. Indeed,southern Mesopotamia, commonly regarded as the birthplace of urbanization, is characterized by a lack of many natural resources: besides its famous abundance of agricultural products including grain, vegetables and fruits, livestock, fish,10Obviously, food security is a prerequisite for the establishment of any larger community. For the Mesopotamian situation, see Reade 1997, who argues that the availability of foodstuffs from various sources, namely the sea, the rivers, the marshes, and agriculture, fostered the establishment of large communities in southern Mesopotamia.and reed, all found in the areas along the coast and the riverbanks, almost every basic ingredient of what we usually define as a highly developed material culture had to be acquired from abroad.11Wilkinson 2012.I will return to this question below. This heavy reliance of the developing urban culture of Mesopotamia on foreign natural resources had very tangible and practical consequences: one needs to acquire them in one way or another.

Guillermo Algaze has described the so-called Uruk expansion in the 4th millennium BC with the help of world-system theory.12Algaze 1993. World system theory was originally developed by Wallerstein 1974 to highlight the complex and multinational character of the European capitalist system that came into being in the 16th century.He describes the Uruk system as an interconnected network, which in turn leads to the assumption that all the nodes in the network (the cities) were dependent on each other, as they were highly specialized and needed a market for their goods. Gil Stein thoroughly discussed Algaze’s approach and provided us with alternative models for the Uruk expansion.13Stein 1999.The exact nature of the spread of the Uruk culture is,as Stein has demonstrated, not entirely clear, and may have varied from place to place. The main explanations for the spread of the Uruk culture are military expansion, colonization by Uruk settlers, the exchange of technology, and trade.14Vallet et al. 2017.

Yet the idea is the following. Acquiring resources requires you to establish and secure supplies, and this very process played an important role in what is usually described as primary state formation,15A primary state is a “first-generation state” that “evolves without contact with any preexisting states.” (Spencer 2010, 7119). For an analysis of the Mesopotamian evidence, see the publications of Norman Yoffee, especially Yoffee 2005.but also as we will see, in secondary state formation. Even if we cannot determine exactly what the Uruk expansion was, we can be sure that during this phase some Mesopotamian technologies of administration and government were exported along the Euphrates and Tigris,and that despite the collapse of this system, its innovations in state administration,such as the invention of writing, outlasted the Uruk expansion. Why? Ever since the Uruk system, resource extraction has characterized successful states, be it violent and exploitative (war-booty), mutually beneficial forms of trade, or more consensual top-down resource extraction (tribute/taxation), this essential policy always entails to a certain degree organizational and administrative technologies.It relies on trained people carrying out standardized procedures (fighting,counting, etc.). Primary states have to develop many things from scratch, while secondary states, which come into contact with preexisting states, have the opportunity to take over knowledge and know-how. Therefore, the formation of secondary states can happen much faster because phases of trial and error can be skipped, already tested solutions can be taken over, and optimized to serve local needs.

Understanding the dynamics of expansion: The case of the East

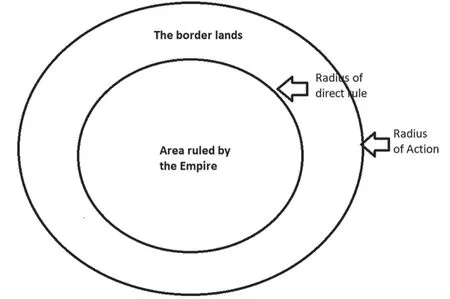

The expansion of every empire is limited by its organizational and technical abilities regarding transportation of troops, supply, and information, or to put it in more abstract terms: by the limitations of its logistical reach.16Engels 1978 gives a broad and insightful discussion of the general logistical problems of ancient armies and focuses on the Macedonian army during Alexander’s campaigns. Marriott and Radner 2015 give a detailed analysis of the logistics of an Assyrian army on campaign in mountainous territory.A glance at the areas ruled by Mesopotamian empires demonstrates that expansion usually went along the rivers as they provided a means of rapid and cheap transportation.While Mesopotamian empires, heirs of the Uruk expansion, tended to conquer and rule cities, the highlands in the East were more problematic for several reasons, but nevertheless highly interesting because of the trade routes that crossed the Iranian highlands. Let us now shift our focus to the border regions and expose our radius theory (Fig. 1). It has already been observed that the military focus of Ur III was never in the West, but rather in the North and the East.

Fig. 1: Radius Τheory.

The radius of direct rule

If we argue that every empire has an ability to rule an area within a certain radius at a given point, then there is a kind of natural limit of expansion. Beyond a certain imaginary line, which I will call the radius of direct rule, the imperial center is no longer able to rule and protect the area because reaction time simply becomes too long to properly respond to different challenges. Obviously, the radius of direct rule is not only defined by the empire alone, but also by natural boundaries like mountains, rivers, and lakes, and the competitors of the empire.In this theoretical framework the explanation for “imperial overstretch” would be that an empire tries to govern regions beyond the radius of direct rule. This inability to correctly assess their own capacities might be one reason for the swift demise of specific imperial political structures.17On short-termed empires, see the contributions in Rollinger, Degen and Gehler 2020.

The radius of action

Βeyond this line, there is another line that is defined by the radius of action of the army.18I thank one of the anonymous reviewers for the reference to Mann 2012, 142, who described the situation in similar terms: “Sargon’s power to rule was less extensive than his power to conquer. [...]The political radius of practicable rule by a state was smaller than the radius of military conquest.”This means that the army is capable of carrying out operations within a certain radius, which is mainly defined by the maximum daily movement of the army, the duration of the campaigning season, and the logistical ability to provide the army with the necessary supplies.

The border region

The land in between these two lines could be defined as the border region. If the empire improves its abilities and enlarges one or the other radius, the former border regions can become part of the empire, and regions totally out of reach can become border regions. In this model, border regions are regions that cannot be directly ruled by the empire, but that interact with the empire in manifold ways. David A. Warburton approached the same problem from a different angle and distinguished “three major types of units – (i) ideological states, (ii)commercial states, and (iii) non-states – as the human social-group actors.”19Warburton 2011, 120.While the Mesopotamian empires would be ideological states in this system,the commercial states were mostly city states with a strong focus on trade in the border zone of the empires.20Ibid., 121.

Working with this model

The political elite of the empire had to decide on the extent of these radii,21Obviously, I do not claim that they used a similar terminology, but they had to face and solve the problems that occurred due to the restrictions we described with the radius of action and radius of direct rule.and to come up with a configuration that fitted their needs and the local situation.The radius of action poses less problems than the radius of direct rule: you can estimate the radius of action of an army by checking the ancient evidence for military campaigns. But it is much harder to determine the radius of rule: it is not always self-evident what type of rule is resorted to, and what was the political and military reasoning that guides their decision. I would argue, however, that if direct rule was feasible there is a strong tendency to execute it.

In the history of empires, we find the development of systems and techniques that are established to push back both of these borders. The establishment of efficient messenger systems, something that we can trace in all Mesopotamian empires, aims at reducing the reaction time of the central government and thereby enhancing its radius of rule.22See the contributions in Radner 2014 on the organization of the communication of large states and empires in antiquity.One of the most successful innovations regarding the radius of direct rule, however, is the establishment of a provincial system that tries to compensate for the long reaction time of the central government by setting up local power centers. Then a given messaging system inevitably becomes even more efficient the shorter the distances to cover are. Τhe establishment of a wellfunctioning standing army tremendously extends the radius of action, as the restrictions concerning the campaigning season no longer apply.

Every empire functions with a different balance, a different configuration of these radii, and my idea is to show that some configurations are more efficient than others. If you are not careful, you very well may end up, like Ur III, cooking up your own defeat.

As already stated above, every complex society in Mesopotamia relied on resources from the neighboring and even far-off regions, and therefore all political entities in Mesopotamia had to guarantee a constant influx of foreign goods.23The Mesopotamians, inhabitants of an alluvial plane lacking natural resources, were well-aware of their dependence on foreign raw materials, and the problem is reflected in the Sumerian epics about Enmerkar and the lord of Aratta (see Vanstiphout 2003 for an edition of these texts) and in the myth“Enki and the World order” where Enki establishes Sumer’s relations with foreign lands.Tin and copper, for instance, two of the basic raw materials needed for the production of bronze, were not available locally and could only be found in remote regions, beyond military reach.24Weeks 2012 provides an overview of the use and the sources of metal in the Ancient Near East.The two basic options for getting such important foreign resources are war and trade.

Translated into the terminology introduced above, we would say that at least some crucial resources were outside the radius of rule, as well as beyond the radius of action. Here we encounter another important radius, the radius of trade that connected Mesopotamia, obviously through many intermediaries, with many parts of the old world.

Therefore, it was essential for Mesopotamian empires to keep the trade routes operational, and this fact was also understood by their enemies, who could block roads, plunder caravans, or simply tax traders. Seemingly this trade was so profitable that all intermediaries wanted to have their share. Steinkeller even suggests that the idea to control and tax trade was the driving force behind the creation of the Sargonic empire.25Steinkeller 2021, 50–51.While smaller states usually have to pick the trade option, empires have a tendency to secure their needs with force, simply because they usually have the necessary size and military power to do so. In some cases, especially in distant and difficult to control mountainous regions without larger settlements and a substantial non-sedentary population, it might seem more reasonable, at least at first sight, not to integrate them into imperial structures of administration. Non-sedentary groups mostly escaped the grasp of administration until modern times, and creative ways had to be found to make them pay taxes,as Daniel Potts demonstrated in a discussion of the Ottoman salt monopoly.26Potts 1984.Hence, every ruler could ask himself if it was worthwhile to create infrastructure and invest manpower and resources in such areas without cities, when it sufficed to send out an army every few years in order to simply take what one needed:animals, humans, metals, precious stones, and everything else that could be taken to Mesopotamia, either as tribute or as booty. Most probably the booty was but a quite positive side-aspect of these operations, and their main aim was to keep the trade routes open. In the same vein, the deportation of populations might have been driven by the idea of removing potential raiders from areas near trade routes,thereby depriving them of the opportunity to attack or tax caravans.

To sum up these considerations: Instead of lagging behind because of a lack of resources, the need for foreign resources propelled the development of complex societies in Mesopotamia. Τhe availability of food stuffs from different sources enabled the Mesopotamians to create large communities. However, the creation of large communities comes at a certain cost. The larger any organization grows the more resources are needed for its administration. Individual freedom is reduced as more rules have to be established to make the coexistence of many people in a relatively small space possible, and a class of administrative specialists comes into being. These specialists have to regulate social problems within the city, but they are also, and maybe mainly, responsible for the influx of all necessary resources. Βecause they control the flow of goods, they have the potential to amass wealth with their specialized knowledge, and in later times when we have royal inscriptions available, we can see that it is one of the duties of the ruler to supply the city with all necessary resources.27Τhe ideology of a prosperous reign is an essential element of Mesopotamian kingship and finds its expression in the idea, expressed in literary texts and in royal inscriptions, that prices are extremely low, or to put it less anachronistically, exchange rates are extremely favorable for the basic products.See Fink 2018.Mario Liverani called these specialists the “non-producers of food,”28Liverani 2006, 7.also often labeled as the elite.29See Sallaberger 2019 on the matter of the elite in Ancient Near Eastern Studies.The elite felt a need to distinguish themselves from the commoners, which becomes more important as a society grows larger, resulting in a rising demand for luxury goods and the public representation of these elites, and their ideologies brought forth buildings of a hitherto unimaginable size.30Liverani 2006, 23–24.In order to protect the cities and their wealth, they had to be fortified, and the increasing population with its increasing demand for foodstuffs made large building projects, especially dams and canals, possible and necessary. The organization of hundreds and thousands of men and women into organized workforces was part of a structure that could be used for other aims as well, namely well-organized warfare.31Schrakamp 2014 discusses the evidence from pre-Sargonic Lagaš and concludes that the manpower of the army was used for military and civil purposes. The situation might be comparable to that of later times, when the armies were much larger – Steinkeller 2021, 66 estimates that the Ur III army might have consisted of 40,000 soldiers.The advantage of Mesopotamian cities over their neighbors in the highlands was clearly the sheer size of the population and the superior knowledge of administration and organization. Michael Mann has described this as the wellorganized agriculturalists’ foot-soldier warfare in contrast to pastoralists’ warfare,usually associated with mounted bands of warriors, which occurred only later in history.32Mann 2012, 132–133.

Pitfalls of warfare

The problem of the war option is that taking booty and demanding heavy tribute from the inhabitants of the looted regions obviously stirs anger and despair among the indigenous population, encouraging them to try to get rid of the invaders.33Michalowski 2011, 4–5: “One can observe certain patterns in all of this martial excess: the search for booty, preemptive strikes against raiders, or the defense of trade and communication routes to areas that were sources of prestige goods, but much of it also seems haphazard and pointless,even taking into account the poor state of our knowledge. In the end all they achieved was the consolidation of powerful new rival polities in the east and this, coupled with an exhaustion of resources and military power, brought about the collapse of the Ur III experiment.”If we assume that many of these mountainous areas were politically divided, not least because of the geography of the region, the onslaught of a large Mesopotamian army would be a disaster for small communities. The most reasonable option for them might have been to flee to the mountains and to leave their belongings behind. Instead of taking up the risky business of attacking wellorganized cities or states, smaller communities seem to be the perfect victims for an army that aims at making booty without much risk. However, when the populations of the mountainous regions learn to defend themselves well enough against the new threat from Mesopotamia, looting becomes too much of a risk and an unprofitable business. Such an investment in defense usually goes hand in hand with the creation of larger structures, be they states, leagues, or federations of tribes. Once they are created and become aware of their military power,they can develop their own political goals and in turn decide to strike back and conquer or loot the rich Mesopotamian cities. Therefore, we might argue, the fall of the Mesopotamian empires may have been caused by their very construction:they depended on foreign resources, and when they were not able to integrate the population of the regions whence the resources came into a system that was rewarding for the local population too, the system could not be sustained for a long time.34So, for example, Michalowski 1978, 47: “One might well inquire, therefore, as to what the peripheral regions received from Ur in return for their obligations. Was the Ur III administration completely exploitative or is there some indication that these areas may have been dependent on Sumer for basic products?”Obviously, I will not argue that the whole of Mesopotamian history can be explained with this model, and thereby seem to suggest that a long-lasting empire like the Neo-Assyrian had an insoluble structural problem. Maybe, and this question could only be answered by a comparative analysis of Mesopotamian empires, the longevity of empires is closely linked to their ability to establish control over trade-routes and transform them to imperial networks, in which the empire presents the central node.35I thank David Warburton for this suggestion.Nor do I want to reduce the manifold relations of Mesopotamia and its neighbors36See Collins 2016 for a long-term analysis of the developments in Mesopotamia and the East.to the resource-aspect. I rather want to highlight the fact that all Mesopotamian states had to deal with the resource problem and find a solution to it, and that we have to consider this fact when describing and analyzing Mesopotamian history.

Τhe effect that states, and the large states that we can call empires in particular,have on their bordering regions is often labeled as “secondary state formation.”37See, for example, Parkinson and Galatay 2007 where a review of the use of this concept is given.When one powerful entity comes into being, its neighbors can use it as a role model in order to reorganize themselves, or we could even argue that the empire itself organizes their neighborhood, as they import their administrative technologies to conquered places and these organizational patterns can be emulated by the locals. As all human societies are reluctant to change their ways without necessity, two things have to come together in order to cause the effect of secondary state formation: the ability and know-how to organize a state and the pressure to do so. Continuous raids of a strong neighbor are a perfect reason to reorganize a society or even create something new. It is not always clear,mainly due to a lack of textual sources from regions outside of Mesopotamia proper, if any state formation was involved in the wars that brought an end to the early empires of Mesopotamia. However, we can be sure that some small mountain tribes were not able to go down to Mesopotamia, defeat well-organized and well-trained armies, and conquer fortified cities. Even if they apply guerilla techniques, these are only useful in their homelands, not for an invading army confronting large armies and cities in a foreign land. However, as numerous examples show, nomad fighters often changed their tactics and adapted their way of warfare once they established themselves as a major player.38Boot 2013, 104.That these people living on the eastern border of the Mesopotamian empires had to organize themselves in some way in order to create an army efficient and big enough to conquer Mesopotamia is obvious. Due to the lack of sources we do not know how they managed it, but we can be quite certain that they profited and learned from the administrative systems that were installed in or adjacent to their region by the Mesopotamian empires.

For the considerations given here, it is important to understand why border regions as the regions beyond the radius of rule but within the radius of action are the regions in which secondary state formation is most likely to occur. Regions under direct imperial rule usually have no chance to develop their own states, and if they tried to do so, the ancients would have described this as rebellion or an attempt to tear apart the larger entity. The regions outside of the radius of action of an empire will not have had much contact with the empire, and it is therefore not very likely that any state formation there can be explained as a reaction to the remote empire.

The cases of Akkad and Ur III

The sources we have at hand for the events at the end of the two 3rd millennium empires in Mesopotamia, the empires of Akkad and Ur III, are mostly literary texts of uncertain date,39The city laments obviously come from a time after the fall of Ur III, but most of them can only be dated vaguely with the exception of the Nippur lament, which mentions king Išme-Dagan of Isin and most probably was performed during a celebration of the renovation of Nippur under this king, see Tinney 1996. The date of the Curse of Agade is not quite certain, most probably it was written in the Ur III period.but all of them describe how foreign invaders from the East came to Mesopotamia and wrought death and destruction.40Claus Wilcke, who wrote the classic account of the decline of Ur III, summarizes the situation as follows (Wilcke 1970, 54): “Versucht man die Ursachen dafür zu fassen, werden neben dem ständig latent vorhandenen Partikularismus und dem Erzfeind Elam in erster Linie die ins Kulturland drängenden Nomaden genannt.”These texts were composed by Mesopotamians themselves and are thus actually expressions of inner-Mesopotamian quarrels, with their own philosophy of history whereby the invasion is the result of divine will: the (Mesopotamian) gods had ordered these people to come down to Mesopotamia.41The most obvious case is the Curse of Agade where it is clearly stated that Enlil sent the Gutians down to Mesopotamia as a punishment for the destruction of his temple, see Cooper 1983. The reasoning of the city laments that describe the disaster at the end of Ur III is more complex; see the introduction of Samet 2014. For an edition and discussion of the royal correspondence of Ur III,letters attributed to Ur III kings that were copied in schools, see Michalowski 2011.In this theological explanation of the events, the agency is hence shifted back to Mesopotamians, and the foreign invaders are relegated to the role of passive tools of the Mesopotamian gods.These texts are good sources if we want to understand how later Mesopotamians imagined the disasters at the end of these empires, but they are surely not the best sources for the reconstruction of historical details, as they do not offer any insight into the reality of warfare. At this point one could conclude that due to the lack of evidence we have no good data concerning the end of the 3rd millennium empires and that we cannot say anything certain as the available sources are highly ideological and from later times.

But there are other sources we can turn to. Generally speaking, the Ur III empire is especially well documented, and we can draw on research already conducted. Thanks to the imperial administration, we have many texts at hand that give us a privileged look into complex administrative processes in general42Molina 2016, 1 estimates that more than 120,000 Ur III tablets are kept in museums today.but also specifically on the interaction of the imperial administration with these border regions.43The classical study is Michalowski’s 1978 article “Foreign Tribute to Sumer during the Ur III Period.” Maeda 1992 formulated the idea that the Ur III empire created a defense zone in the east. On both topics, see Garfinkle 2014 and Hebenstreit 2014.But let us start by sketching the history of Ur III.

The Ur III empire was preceded by the empire of Akkad (c. 2344 – c. 2154 BC),the first “well-documented” empire of ancient Mesopotamia.44For a recent summary of our knowledge about the Akkadian empire, see Foster 2015.After a period of rapid expansion under Sargon, with intensive campaigning in all directions, his successors had to face major rebellions, and the empire seems to have collapsed after an attack from the Iranian highlands. The numerous campaigns of the Akkadian kings in the East might have triggered political changes there, and at the beginning of the reign of Ur-Namma we already see the dynasty of Šimaški in place.45See Steinkeller 2014 for an historical overview of this dynasty and for a discussion of the location of its territory.We do not have too much information concerning the period between the end of the empire of Akkad and the beginning of Ur III, but we know that there were foreign kings – the Guti. The Guti were defeated by Utuhegal, whose relationship to the founder of the Ur III dynasty, Ur-Namma, is not clear, but most probably they were relatives.46See Sallaberger 1999 for an overview of the history of Ur III.Ur III is conventionally dated from 2112–2004 BC,thereby lasting 108 years. Ur-Namma was the founder of the Ur III dynasty, his successor Šulgi reigned for 48 years, and from the middle of his reign onwards we have an abundance of administrative tablets as well as the frequent appearance of military campaigns in year names.47Steinkeller 2021, 59 speaks of an “explosion of evidence” after Šulgi’s reforms.Šulgi was succeeded by Amar-Suena, who was succeeded by Šu-Sin, and the empire collapsed under Ibbi-Sin, who was defeated by the Elamites and led into captivity in Elam. These are the facts that can be established from the textual evidence, but in order to understand the fall of this empire, we must return to the structural challenges of all Mesopotamian empires and one of the most urgent challenges is the need for imports.

One way to study these imports is to have a look at the numerous foreign rawmaterials and objects found in Mesopotamia. One must note here that although it is clear that most of the surviving prestige objects, weapons, and tools are made of imported materials, we unfortunately do not know how the material or the objects got to Mesopotamia. When we find foreign objects or materials, we almost immediately think of trade, but as Kerstin Droß-Krüpe reminds us there are many options to consider when speculating on how objects could get from one place to another long ago and the objects themselves are not accompanied by documents:

So not all exchange processes are automatically to be called trade; not every“exotic” object came to the place where it was found by means of trade. Other distribution channels as presents, subsidies, tributes and booty, should not be neglected, though it is certainly often difficult to identify them.48Droß-Krüpe 2014, x.

Resources can be acquired in many ways, and the borders between different categories are often blurred. If we make a distinction between presents and tribute, we might hint at the fact that the giving party can regard some objects as presents for a friend, while the receiver might call them tribute.49See Sharlah 2005 for a discussion of foreign “gifts” for the Ur III court.Keeping these many options and their ideological implications in mind, we can state that the two basic options for acquiring goods are trade or war. The “sender” of a given object can give the object in exchange for something else, or he can be forced to give to the “receiver.” I articulated these questions in an article the title of which was, according to the volume’s focus on textiles: “war or wool?”50Fink 2016.

We can find quite a lot of evidence for both options in the Mesopotamian sources. Several inscriptions boast about the king making booty in foreign lands,and others – so, for example, some inscriptions of Gudea of Lagaš – rather claim that the foreign goods kept flowing into the capital by themselves.51The motif is especially evident in Gudea Statue B. For an edition and translation, see Edzard 1997,30–38.One of the tropes in royal inscriptions is the image of the heroic king, who fights his enemies, which are often designated as rebels against the universal rule of the righteous king.52On the concept of the rebel lands, see Kinnier-Wilson 1979. For a recent treatment of the concept of heroic kingship, see Ponchia 2019.Τhe Stele of Narām-Sîn of Akkad is a prominent example. Here the king is depicted as the largest and most prominent figure. Irene Winter spoke of the “alluring body of Naram-Sîn,” and on this stele the king is even wearing a horned crown, the headdress of gods.53Winter 1996.Similar steles also existed in Ur III, but none of them has survived, and we only know the texts of some of them from later copies (see below). In steles which usually praise the heroic qualities of the king booty is also mentioned, but trade is obviously not the focus of these texts as they aim at depicting the heroic side of the king. Here is one example from Narām-Sîn’s inscriptions, a statue-base from Susa, which mentions important raw-material, namely the material for the statues of the rulers:

He [Narām-Sîn] conquered Magan […]. In their mountains he quarried diorite stone and brought it to Agade, his city, and fashioned a statue of himself.54Frayne 1993, 117–118.

(ii 1–16)

We can easily imagine that the text pointed to exactly the statue made of exotic stone that Narm-Sîn fashioned of and for himself and that stood on this base.From the empire of Akkad, we have several stone-objects that were found in temples bearing inscriptions identifying them as booty. In both cases the claim of having made exotic and valuable booty is proven by the object itself.55Potts 1989.So booty was surely one way for certain goods to enter Mesopotamia.

Our information on Ur III military campaigns mainly comes from year names,as years were given a name that memorializes one important event of that year.Τypical names documenting military actions are “Year city X was destroyed” or“Year city X was destroyed for the nth time.”56On the Ur III year-names mentioning war, see Such-Gutiérez 2020.The royal inscriptions also inform us about campaigns, but if we compare them to the frequency of warfare in year names, we can come to the conclusion that war was not the focal point of Ur III inscriptions.57See Fink 2016 for a discussion of battle and war in the royal self-representation of the Ur III period.However, a few of the inscriptions boast about booty, and in an inscription of-Sn we even find a parallel to the text quoted above concerning the fashioning of a statue out of material captured during a campaign:58The claims of this text were recently checked against the evidence of the administrative texts in Langa-Morales 2020.

He blinded the men of those cities, whom he had overtaken, and established them as domestic (servants) in the orchards of the god Enlil, the goddess Ninlil and of the great gods. And the [wom]en of [those cities], whom he had overtaken, he offered as a present to the weaving mills of the god Enlil, the goddess Ninlil and of the great gods. Τheir cattle, sheep, goats and asses he [led away] and offered them in the temples of [the god E]nlil, [the goddess Ninlil and the temples of the great gods]. He filled leather sacks with [go]ld (and) silver, and [items fash]ioned(from them). He loaded cop[per], its tin, bronze (and) items fashioned from them on pack-asses. He (thereby) provided treasure for the temples of the god Enlil,the goddess Ninlil, and of the great gods. […] At that time, Šū-Sîn, mighty king,king of Ur, king of the four quarters, fashioned into an image of himself the [si-]lver of the [l]ands of Simaški which he had taken as booty.

(iv 15 – vi 29)59Frayne 1997a, 304–305 (E3/2.1.4.3).

Despite the large number of royal inscriptions from the Ur III period, we do not have much information regarding campaigns and booty, as most of the surviving royal inscriptions are building inscriptions,60Building inscriptions were often made of clay or stone and were buried in deposits, while steles and statues (with their focus on the heroic deeds of the king) were often made of precious materials and exhibited in temples or public places and therefore often fell victim to looters. For this reason, the surviving evidence might be somewhat misleading, even if the Mesopotamian scribes of later periods copied the inscriptions of Ur III statues and steles.and the others usually give no quantification and rely heavily on tropes – the two tables summarize the evidence regarding booty and trade (Tables 1 and 2).

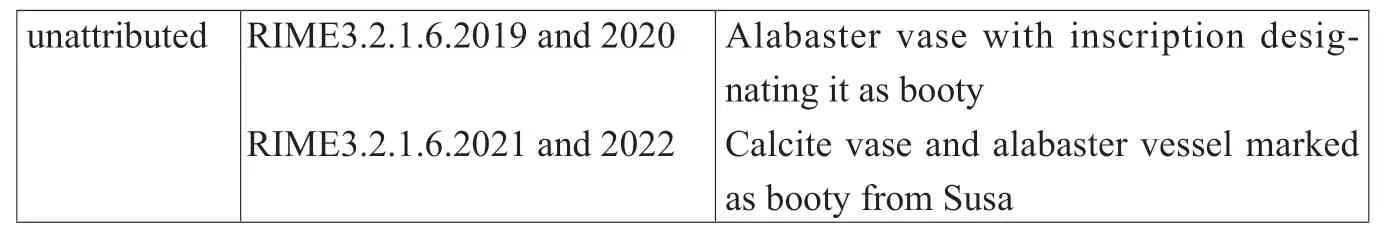

Τable 1: Βooty in Royal Inscriptions of the Ur III period.

Notes: a) Here I follow the interpretation of Douglas Frayne. However, the text does not mention booty (nam.ra.ak) explicitly; b) The kings of Ur kept various exotic and dangerous animals, which are documented in the administrative record. For an analysis,see Such-Guttierez 2019.

Τable 2: Τrade in Royal Inscriptions of the Ur III period.

If we wish to summarize the evidence as presented in these two tables, we can conclude that animals, people, and metals were mentioned as booty, and that foreign objects were dedicated to the temples. When the texts localize the booty then it comes from the East (Elam, Susa, Simaški).

Administrative documents sometimes confirm claims made in year-names or inscriptions, most often by mentioning incoming booty from campaigns.Unfortunately, we still have to make many assumptions about the exact nature of many deliveries, as the main aim of the administrative documents is to keep track of the flow of goods and not to describe the ins and outs of the system as a whole, as the people involved in the system knew how it functioned, and were not interested in explaining it to us. Some recent studies of these large archives have,however, improved our understanding of the big centers of Ur III administration.61As this paper was held in Changchun one should not forget to mention the initiative of Wu Yuhong,who fostered Ur III studies in China. One of outcomes of his efforts is Changyu Liu’s 2017 book on Puzriš-Dagan as “a redistribution center for animals and various products” (Liu 2017, 3).A better understanding of this organization and the role of certain individuals will ultimately contribute to an improved understanding of the overall functioning of the Ur III state.

The administrative texts mentioning booty (nam-ra-ak) were analyzed recently by Steven Garfinkle and Laurent Hebenstreit.62Garfinkle 2014; Hebenstreit 2014.Garfinkle lists 49 texts mentioning booty from various places63Anšan, Harši, Hurti, Kimaš, Šara, ariphum, Šašru, Šimaški (LU2.SU), Šurudhum, Urbilum, uru dMes-lam-ta-e3-a, uru dNergal-ki.and 13 texts mentioning booty from the Martu.64Garfinkle 2014, 360–362.The booty obtained in the first group consists of food, sheep, cattle, leather, silver,male and female prisoners. The Martu texts mention cattle, donkeys, and sheep.Except for metal and slaves all these would also be found in Mesopotamia, so we can conclude that the materials mentioned in the administrative texts do not indicate that the campaigns aimed at or were especially successful in capturing resources that were not available in Mesopotamia. However, the establishment of a mine mentioned in RIME3.2.1.4.1 vi 8–18 hints to the fact that they were aiming at more reliable long-term solutions to the problems at hand. The establishment of mines in not fully controlled land was a method sometimes used in Ur III times, traces of which appear in the administrative texts.65Langa-Morales 2020, 147–148.

While the option of not imposing direct rule on hard-to-control areas and to pacify them by occasional military operations might seem reasonable and work out well over the short term, it has been suggested that it might have been a momentous mistake of the Ur III kings not to properly integrate the military dominated territories into their realm but rather to use them as a playground for the wars of the imperial elite.66Garfinkle 2014, 358–359: “Βy the latter half of Šulgi’s reign, the Ur III state had entered an era of total warfare that was aimed neither at defense nor outright conquest. What I am suggesting is the development of a prestige economy that resulted in a state of affairs in which domestic socioeconomic concerns amongst the elite drove decisions about warfare rather than state level strategic concerns.”However, there are also other opinions and in an article summarizing some of the findings of his long-awaited book on the“Grand Strategy of Ur III,” Steinkeller claims that the main reason “behind the failure of the Ur III ‘Grand Strategy’ is likely the fact that, rather than on raw military power, it relied too much on diplomatic arrangements with its allies and vassals.”67Steinkeller 2021, 69.But even if there exist diverging opinions about the intensity of Ur III warfare,68The numerous references to warfare in the Ur III year-names, of which Such-Guttierez 2020, 23–28 lists 27, do indicate a high frequency of warfare, especially if we consider that not all campaigns were documented in the year names. This is made evident by the non-appearance of war in the year names of Ur-Namma, the founder of Ur III, who obviously was involved in military activities to create the core of the future empire.there seems to be a consensus that the lack of the will or ability to directly govern border areas was a cause for the ultimate downfall of Ur III.It is hard for us to decide whether it would have been feasible for the Ur III kings to rule these areas directly, but it is obvious that at least for a certain time the necessary occupational forces would have reduced the offensive abilities of Ur III.69See Mann 2012, 142–146 for a thorough discussion of different modes of rule in early empires.Hard-to-control mountainous regions have always been a problem for would-be superpowers, as the example of Afghanistan has repeatedly demonstrated in recent times, and we must concede that our actual knowledge about the details of the military activities in these regions is very limited.70Our knowledge about most campaigns, comes from year names, so we are only aware of the fact that there was a campaign, and in most cases we have no information about any military details.

As mentioned above, we usually distinguish between booty, tribute (presents),and taxation. We define booty as the sum of goods acquired through force (to whatever degree) or the simple threat of an approaching army during a campaign –without war, there is no booty. Tribute is more institutionalized than booty,as it is, at least in theory, a regular payment that is organized by a local ruling class and delivered in some form to the one receiving it. As the two examples presented in the table above (RIME3.2.1.4.6 and RIME3.2.1.5.4) demonstrate tribute was also mentioned in royal inscriptions. Taxation, which usually does not occur as a heroic deed of the king in his inscriptions, means that conquered territories are turned into provinces and are ruled by direct administration.

In the Ur III period two different models of taxation existed. The provinces paid bala-taxes, while the border regions, or better the military units stationed there, had to pay the gún (later: gún ma-da) tax. Additionally, there existed direct payments to the king called máš-da-ri-a, which were mainly used for the most important festivities in Ur, and the nisaĝ offerings for the new year festivities in Nippur.71See Schrakamp and Paoletti 2011, 163–164 with references to further literature.For me, the main difference between tribute and taxation is that taxes are raised directly from the population under the rule of the empire, while tribute is raised from the rulers of political entities. The ancient terminology is not very helpful in this case as gún is used for tribute and tax alike in Ur III times. To sum up the evidence: if we want to be consistent with Ur III terminology we might call everything that came from provinces a “tax,” and speak about “tribute” if the areas are outside the provincial system. However, it seems to be a difference to me if the tribute is collected in an area with military outposts or given by an independent ruler.

Each of these options has its advantages and disadvantages and, as Andreas Fuchs has pointed out recently, it might take a very long time to turn partly conquered and plundered areas into provinces as we must bear in mind that besieging a well-fortified city is a risky military undertaking and a costly logistical burden.72Fuchs 2008.He highlighted the fact that it took the Neo-Assyrian empire,with its highly developed military, several generations to break the power of the local dynasties of today’s Syria by defeating them on the field, making booty and demanding tribute, gradually securing the tribute over the long term, having turned formerly autonomous local rulers into loyal vassals. These loyal Assyrian vassals then had to extract taxes from their local population in order to pay tribute to Assyria, which in turn made them unpopular, and – at some point – it seemed more attractive for the population to be directly governed by the Assyrians.Therefore, the system of successful long-term imperial conquest often follows the three steps: booty – tribute – taxation (and the latter two distinctions are not always visible in the textual documentation, except where other sources allow us to recognize the process).

This example from the Neo-Assyrian empire should demonstrate that it is not easy to establish the long-term aims of Ur III rulers – where we lack the relevant texts and the regime lasted only a century, while several generations of rulers would have been needed to turn far away and well-defended areas into provinces.But what kind of evidence do we have for the military actions of Ur III? We know that the military focus of Ur III was to the North and the East.73Sallaberger and Westenholz 1999, 159.Bertrand Lafont stated that “[d]anger (and especially the ‘Amorite’ danger) never came from the west for the kings of Ur.”74Lafont 2009.At this point we can ask ourselves why the orientation of Ur III did not go along the Euphrates to the West, where transportation and therefore also the organization of military and administrative matters would have been so much easier than in the mountainous area of the East.It seems that Amorite raids from the North forced the Ur III kings to be active there and most probably the activities in the East were aimed at keeping the trade routes open and at generating booty during these operations.75Garfinkle 2014, 357.The Ur III army obviously needed to be concentrated to carry out effective operations against enemy territories: if the Ur III kings would have opened a second or third front in the West, this might have caused severe problems and taken valuable troops from their stations in the North and the East. Therefore, it seems only natural that the Ur III kings relied not only on their army (which was seemingly not strong enough to defeat everyone) but used diplomacy76Sharlach 2005 analyzes the evidence for diplomats in the Ur III evidence.and dynastic marriages77See Michalowski 1975 for the analysis of one specific, failed case of a diplomatic marriage.Weiershäuser 2008, 261–264 discusses the evidence of dynastic marriages.in order to establish peaceful relations with some of their neighbors in order to have secure borders, where only a few soldiers had to be garrisoned. This mixture of diplomacy and military force seems to be part of the political game, and only too often allies of today became the enemy of tomorrow; the best Mesopotamian example for such a Machiavellian approach to politics might be provided by the politics of Hammurapi.

Garfinkle stated that since the middle of Šulgi’s reign, Ur III was involved in“total warfare.”78Garfinkle 2014, 357. See also id. 2013, especially 160–162.There is plenty of evidence for continuous military activities,however we are not sure about the scale of these operations, and perhaps the term“total war” bears misleading associations with modern warfare. However, the fact remains that military actions took place and were celebrated in inscriptions and year names – what could be the explanation for this? In an initial phase,the territorial basis for the empire had to be laid by means of military conquest.According to the quite convincing reconstruction of Gianni Marchesi, we have evidence for Ur-Namma’s conquest of Susa, although the other sources remain quite silent about the obvious warfare of the founder of the dynasty.79Marchesi 2009.This would mean that already Ur-Namma conducted large-scale military operations outside of the core-area of southern Mesopotamia, and that the area of influence was already largely defined by his military activities.

Another reason for warfare, prominently put forward by Tohru Maeda,80Maeda 1994.is defense. Maeda developed the idea that Ur III created buffer states, a defense zone, in the East. However – and this is the question of most interest here –, was it not the creation of this “defense zone,” which Garfinkle considered a misnomer for an exploited territory,81Garfinkle 2014, 359.that brought about the transfer of administrative and military knowledge to vassals and/or allies who were also potential competitors and rivals, and thus the prime reason for Ur III’s downfall?

The reason for the exploitation of this area was the need for foreign resources in order to keep the empire working. The vital trade routes to the East and Northeast needed to be protected, in order to keep the metal-supply coming in and additionally, as pointed out by Garfinkle, there is the sociological factor,that this kind of booty-warfare provided a great business-opportunity for the Mesopotamian elites. A successful undertaking in these areas could provide them with riches and increase their status in the ranks of the empire and as well provide the king with the opportunity to create a loyal elite by continuously supplying them with their share of the operations in the East.82Ibid., 357–358.

Returning to our initial idea of Mesopotamia as aMängelwesen, let us consider once more why foreign resources were so essential for Mesopotamia. When we think of advanced weaponry, which heavily relies on the use of metal, it becomes clear that the Mesopotamians needed metal imports in order to manufacture the weapons they needed. It appears to be a kind of paradox that only trade enabled the Mesopotamians to defeat their trading partners.83The problem was seemingly understood in Neo-Assyrian times, when the king complains about merchants selling iron to the Arabs (SAA 1 179).Obviously, they also had organizational advantages over most of their foes, as they were able to organize and maintain a large-scale army. Nevertheless, as essential metals for weaponry came from far-away places that were not ruled by Ur III, exchange goods for trade were still needed. The evidence for Mesopotamian exports from the third millennium is so scarce that Harriet Crawford spoke about Mesopotamia’s invisible exports.84Crawford 1973.Successful exports are based on two things: there has to be a market for the product, and the costs of manufacturing and transporting it have to be reasonable in relation to the goods that are exchanged for them. While this might sound anachronistic, a simple example should make clear that technical restrictions also apply for antiquity: If someone transports grain on donkeys(with a load of 60 kilos) and these donkeys have to eat 3 kilos of grain a day, no grain will be left after 20 days. So, transporting grain over longer distances only makes sense when the price is especially high, as, for example, during times of starvation, and when the transportation is easy and cheap, which is usually the case if grain can be transported on boats, but usually high-priced products like textiles were the choice for Mesopotamian exports. The production of textiles was labor-intensive, and therefore also the textile industry partially depended on a workforce captured during campaigns.85RIME3.2.1.4.3 iii 22 – iv 31 and many na-ra-ak texts mention people as booty. A comparative analysis of women in textile industry is found in Uchitel 2002.

This pressure to maintain a technological advantage and secure the import of resources to Mesopotamia with the production of sought-after exchange goods might have been the main reason for the development of a Mesopotamian industry producing textiles and metal objects. Benjamin Foster highlighted the example of metallurgy in the Akkad empire:

Mesopotamian metallurgy is one of the first instances in history of a sophisticated industry based entirely on imported raw materials, in which superior technology compensated for lack of resources.86Foster 2014, 114.

Another example is the establishment of a large-scale textile industry in Ur III times, which might be related to the significant decline of the price of wool compared to earlier periods and the idea of making better use of the available resources in Mesopotamia.87The classic study of the Ur III textile industry is Waetzoldt 1972.

I hope I have made my point sufficiently clear that both trade and war were essential for securing resource-supply in Mesopotamia, but trade and war never affect only one side – they have effects on all parties that are involved in this enterprise. Trade, tribute, and taxes created connections between the center of the empire and a set of different regions that resulted in a network of mutual dependencies between different places. Though the relations were not only exploitative and hence also benefited the regional trade partners, the flow of goods organized by the Mesopotamian empires mainly focused on the Mesopotamian heartland: when the system worked well, the center of the network profited the most. Τhis also explains why it was the center that suffered the most when the system broke down. The homemade disaster, as announced in my title, is the fall of the Mesopotamian empires. Let us have a short look at the reasons that are usually given for the downfall of the empires of Akkad and Ur III. If we check a random historical overview of this period, we are very likely to find the rise of new enemies, foreign attacks, and separatism as causes for the downfall or Ur III.

As already stated above, these new enemies and their attacks on Mesopotamia were most probably caused by the continuous warfare of Ur III in the border regions. The separatism within the core of Ur III arose when the rulers of Ur III were already weakened and the system of the redistribution of booty collapsed,and is thereby also closely connected with the formation of the new enemies.At this point, we come to understand that Mesopotamia is no island, even if the conception of the famous Babylonian map of the world represents it as one. Already in antiquity Mesopotamia was heavily interconnected with and dependent on the adjacent regions. Our understanding of these interconnections can profit from describing the Ancient Near East by the model of a world-system,which was defined by Christopher Chase-Dunn and Τhomas Hall as follows:

We define world-systems as intersocietal networks in which the interactions (e.g.,trade, warfare, intermarriage) are important for the reproduction of the internal structures of the composite units and importantly affect changes that occur in these local structures.88Chase-Dunn and Hall 1993, 855.

To sum up, these dependencies were manifold already in the third millennium.Mesopotamia was part of a world-system and had to find its role in an interconnected world. Without these inter-societal networks, no Mesopotamian army would have been able to defeat its foes, no large-scale representative buildings would have been possible, and no additionally trade, warfare, and foreign luxury objects would have provided Mesopotamian elites with the possibility to distinguish themselves from ordinary people and thereby create an elite culture.These imports were “important for the reproduction of the internal structure” of the Mesopotamian empires, and they affected “changes that occur in these local structures.”

The Mesopotamian empires were interwoven in structures of their own creation upon which they were dependent. No Mesopotamian empire was able to ensure the supply of the most important resources from its own territory –the first imperial entity in the Ancient Near East that was able to do so was the Achaemenid empire with its immense territory spanning the Indus and the Danube; this empire also came to rest at borders beyond which it was seemingly not interested in expanding. It was a world-system in itself, but nevertheless it, too, triggered processes beyond its borders that finally likewise led to its downfall. This lack of resources within the own area of control might be one explanation why Mesopotamian empires had the stable tendency to expand;they simply needed to secure access to resources and protect the trade routes.But, as demonstrated here, this expansion is a tricky business: interactions originally established to integrate an area can trigger processes that ultimately lead to the disintegration of the system. War and regular booty extraction in the border regions trigger the reaction of the locals who retaliate by reorganizing themselves, forming alliances, and pushing back.

Τo finally answer my initial question – was the downfall of Ur III a homemade disaster? Yes. It seems very convincing that the pressure executed by the Ur III state on its border regions made new enemies arise. Finally, the imperial aspirations of Ur III suffered from the simple fact that they were dependent on resources from the East – the region they decided to overthrow, as Garfinkle has put it, with “total warfare […], in which domestic socio-economic concerns amongst the elite drove decision about warfare rather than state level strategic concerns.”89Garfinkle 2014, 357–358.The ability to conduct war and make booty in these regions, but the unwillingness or inability to finally conquer and administer them might have been the main cause for the fall of Ur III.

Transferred to the terminology used above we could say that the large radius of action and the seemingly significantly smaller radius of direct government finally caused the downfall of Ur III. This leads to the more general conclusion that the ability and willingness to conduct campaigns in far-away regions combined with the inability to put them under direct rule creates a huge border region which is especially suited for secondary state formation. The validity of this consideration should be tested against the background of more historical examples.

Bibliography

Algaze, G. 1993.

The Uruk World System. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Boot, M. 2013.

“The Evolution of Irregular War: Insurgents and Guerrillas from Akkadia to Afghanistan.”Foreign Affairs92/2: 100–114.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Hall, T. D. 1993.

“Comparing World-Systems: Concepts and Working Hypotheses.”Social Forces71: 851–886.

Collins, P. 2016.

Mountains and Lowlands. Ancient Iran and Mesopotamia. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum.

Cooper, J. 1983.

The Curse of Agade. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Droß-Krüpe, K. 2014.

“Textiles Between Trade and Distribution. In Lieu of a Preface.” In: ead. (ed.),Textile Trade and Distribution in Antiquity / Textilhandel und -distribution in der Antike. Philippika 73. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, vii–xii.

Edzard, D. O. 1997.

Gudea and his Dynasty. Τhe Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Early Period 3/1. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Engels, D. 1978.

Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army. Los Angeles:University of California Press.

Fink, S. 2016.

“War or Wool? Means of Ensuring Resource-Supply in 3rd Millennium Mesopotamia.” In: K. Droß-Krüpe and M.-L. Nosch (eds.),Textiles, Trade and Theories.From the Ancient Near East to the Mediterranean. Kārum – Emporion – Forum 2.Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 79–92.

—— 2016a.

“Βattle and War in the Royal Self-Representation of the Ur III Period.” In:Τ. R. Kämmerer, M. Kõiv and V. Sazonov (eds.),Kings, Gods and People.Establishing Monarchies in the Ancient World. Alter Orient und Altes Testament 390/4. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 109–134.

—— 2018.

“Assurbanipal, der Wirtschaftsweise: Einige Überlegungen zur mesopotamischen Preistheorie.” In: K. Ruffing and K. Droß-Krüpe (eds.),Emas non quod opus est, sed quod necesse est: Beiträge zur Wirtschafts-, Sozial-, Rezeptions- und Wissenschaftsgeschichte der Antike. Festschrift fr H.-J. Drexhage zum 70.Geburtstag. Philippika 125. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 131–141.

Foster, B. 2015.

The Age of Agade: Inventing Empire in Ancient Mesopotamia. London:Routledge.

Frayne, D. 1993.

Sargonic and Gutian Periods.Τhe Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Early Periods 2. Toronto: Toronto University Press.

Fuchs, A. 2008.

Garfinkle, S. J. 2013.

“The Third Dynasty of Ur and the Limits of State Power in Early Mesopotamia.”In: id. and M. Molina (eds.),From the 21st Century B.C. to the 21st Century A.D.Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 153–167.

—— 2014.

“The Economy of Warfare in Southern Iraq at the End of the Third Millennium BC.” In: H. Neumann et al. (eds.),Krieg und Frieden im Alten Vorderasien. 52e Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale. International Congress of Assyriology and Near Eastern Archaeology Münster, 17.–21. Juli 2006.Alter Orient und Altes Testament 401. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 353–362.

Gehlen, A. 1988.

Man. His Nature and Place in the World.Trans. by C. McMillan and K. Pillemer.New York: Columbia University Press.

Hebenstreit, L. 2014.

“The Sumerian Spoils of Warfare in Southern Iraq at the End of the Third Millennium BC.” In: H. Neumann et al. (eds.),Krieg und Frieden im Alten Vorderasien. 52e Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale. International Congress of Assyriology and Near Eastern Archaeology Münster, 17.–21. Juli 2006.Alter Orient und Altes Testament 401. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 373–380.

Kinnier-Wilson, J. 1979.

The Rebel Lands: An Investigation into the Origins of Early Mesopotamian Mythology.New York: Cambridge University Press.

—— 2005.

“On the ud-šu-bala at Ur toward the End of the Third Millennium.”Iraq67:47–60.

Lafont, B. 2009.

“The Army of the Kings of Ur: The Textual Evidence.”Cuneiform Digital Library Journal5: 1–25.

Langa-Morales, C. 2020.

“Der Feldzugsbericht in Šū-Sîns Königsinschriften im Vergleich zu Verwaltungsurkunden: Die Grenze zwischen Erzhlung und Geschichte im Rahmen der Knigsdarstellung.” In: E. Wagner-Durand and J. Linke (eds.),Tales of Royalty.Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter, 139–154.

Liu, Changyu. 2017.

Organization, Administrative Practices and Written Documentation in Mesopotamia during the Ur III Period (c. 2112–2004). A Case Study of Puzriš-Dagan in the Reign of Amar-Suen. Kārum – Emporion – Forum 3. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag.

Liverani, M. 2006.

Uruk. The First City.Ed. and Trans. by Z. Bahrani and M. Van De Mieroop.London: Equinox.

Maeda, T. 1992.

“Τhe Defense Ζone During the Rule of the Ur III Dynasty.”Acta Sumerologica14: 135–172.

Mann, M. 2012.

The Sources of Social Power.vol. 1:A History of Power from the Beginning to AD 1760. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marchesi, G. 2009.

“Ur-Nammâ(k)’s Conquest of Susa.” In: K. de Graf and J. Tavernier (eds.),Susa and Elam. Archaeological, Philological, Historical and Geographical Perspectives.Leiden & Boston: Brill, 285–291.

Marriott, J. and Radner, K. 2015.

“Sustaining the Assyrian Army among Friend and Enemies in 714 BCE.”Journal of Cuneiform Studies67: 127–144.

Michalowski, P. 1975.

“The Bride of Simanum.”Journal of the American Oriental Society95: 716–719.

—— 1978.

“Foreign Tribute to Sumer during the Ur III Period.”Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie68: 34–49.

—— 2011.

The Correspondence of the Kings of Ur. An Epistolary History of an Ancient Mesopotamian Kingdom.Mesopotamian Civilizations 1. Winona Lake, IN:Eisenbrauns.

Molina, M. 2016.

“Archives and Bookkeeping in Southern Mesopotamia during the Ur III Period.”Comptabilités8: 1–19, accessible under: http://journals.openedition.org/comptabilites/1980 (23.01.2020).

Nippel, W. 2020.

“Das Formationsschema und die ‘Asiatische Produktionsweise’.” In: C. Deglau and P. Reinard (eds.),Aus dem Tempel und dem ewigen Genuß des Geistes verstoßen? Karl Marx und sein Einfluss auf die Altertums- und Geisteswissenschaften. Philippika 126. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 87–106.

Parkinson, W. A. and Galaty, M. L. 2007.

“Secondary States in Perspective: An Integrated Approach to State Formation in the Prehistoric Aegean.”American Anthropologist109: 113–129.

Potts, D. 1984.

“On Salt and Salt Gathering in Ancient Mesopotamia.”Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient27: 225–271.

Potts, T. F. 1989.

“Foreign Stone Vessels of the Late Third Millennium B.C. from Southern Mesopotamia: Their Origins and Mechanisms of Exchange.”Iraq51: 123–164.

Powell, M. A. 1985.

“Salt, Seed and Yields in Sumerian Agriculture. A Critique of the Τheory of Progressive Salinization.”Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie75: 7–38.

Radner, K. (ed.). 2014.

State Correspondence in the Ancient World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Reade, J. 1997.

“Sumerian Origins.” In: I. L. Finkel and M. J. Geller (eds.),Sumerian Gods and their Representations.Groningen: Styx, 221–229.

Rollinger, R., Degen, J. and Gehler, M. (eds.). 2020.

Short-term Empires in World History.Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Ross, M. L. 2015.

“What Have we Learned about the Resource Curse?”Annual Review of Political Science18: 239–259.

Sallaberger, W. 2019.

“Who is Elite? Two Exemplary Cases from Early Bronze Age Syro-Mesopotamia.” In: G. Chambon, M. Guichard and A.-I. Langlois (eds.),MélangesAssyriologiques en l’honneur de D. Charpin.Leuven, Paris & Bristol: Peeters,893–921.

Sallaberger, W. and Westenholz, A. 1999.

Mesopotamien: Akkade Zeit und Ur III Zeit. Orbus Biblicus Orientalis 160/3.Fribourg: University Press.

Samet, N. 2014.

The Lamentation over the Destruction of Ur.Mesopotamian Civilisations 18.Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

Schrakamp, I. 2014.

“Krieger und Βauern. RU-lugal und aga3/aga-us2im Militär des altsumerischen Laga.” In: H. Neumann et al. (eds.),Krieg und Frieden im Alten Vorderasien.52e Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale. International Congress of Assyriology and Near Eastern Archaeology Münster, 17.–21. Juli 2006.Alter Orient und Altes Testament 401. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 691–724.

Schrakamp, I. and Paoletti, P. 2011.

“Steuer. A.”Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie13:161–164.

Sharlach, T. 2005.

“Diplomacy and the Rituals of Politics at the Ur III Court.”Journal of Cuneiform Studies57: 17–29.

Spencer, C. S. 2010.

“Territorial Expansion and Primary State Formation.”Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America107: 7119–7126.

Stein, G. 1999.

Rethinking World-Systems. Diaspora, Colonies, and Interaction in Uruk Mesopotamia. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.

Steinkeller, P. 2014.

“On the Dynasty of Šimaški: Τwenty Years (or so) after” In: M. Kozuh et al. (eds.),Extraction & Control. Studies in Honor of M. W. Stolper.Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilizations 68. Chicago: The Oriental Institute, 287–296.

—— 2021.

“The Sargonic and Ur III Empires.” In: P. F. Bang, C. A. Bayly and W. Scheidel(eds.),The Oxford World History of Empire. vol. II:The History of Empires.Oxford: Oxford University Press, 43–72.

Such-Gutiérrez, M. 2019.

“Man and Animals in the Administrative Texts of the End of the 3rd Millennium ΒC.” In: R. Mattila, S. Ito and S. Fink (eds.),Animals and their Relation to Gods,Humans and Things in the Ancient World. Wiesbaden: Springer, 411–453.

—— 2020.

“Year Names as Source for Military Campaigns in the Τhird Millennium ΒC.” In:J. Luggin and S. Fink (eds.),Battle Descriptions as Literary Texts. A Comparative Approach. Wiesbaden: Springer, 9–29.

Tinney, S. 1996.

The Nippur Lament. Royal Rhetoric and Divine Legitimation in the Reign of Išme-Dagan of Isin (1953–1935 B.C.).Philadelphia: The Samuel Noah Kramer Fund.

Uchitel, A. 2002.

“Women at Work: Weavers of Lagash and Spinners of San Luis Gonzaga.” In:S. Parpola and R. M. Whiting (eds.),Sex and Gender in the Ancient Near EastII.Proceedings of the XLVIIe Rencontre Assyriologique in Helsinki. Helsinki: Neo Assyrian Text Corpus Project, 621–631.

Vanstiphout, H. 2003.

Epics of Sumerian Kings. The Matter of Aratta. Writings from the Ancient World.Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature.

Waetzoldt, H. 1972.

Untersuchungen zur neusumerischen Textilindustrie. Studi Economici e Tecnologici 1. Rome: Instituto per l’Oriente.

Wallerstein, I. 1974.

The Modern World SystemI. San Diego: Academic Press.

Warburton, D. A. 2011.

“What Might the Bronze Age World-System Look Like?” In: T. C. Wilkinson,S. Sherratt and J. Bennet (eds.),Interweaving Worlds. Systemic Interactions in Eurasia, 7th to 1st Millennia BC. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 120–134.

Weeks, L. 2012.

“Metallurgy.” In: D. T. Potts (ed.),A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Chichester: Blackwell, 295–316.

Weiershäuser, F. 2008.

Die königlichen Frauen der III. Dynastie von Ur.Göttinger Βeiträge zum Alten Orient 1. Göttingen: Universitätsverlag.

Wilcke, C. 1970.

“Drei Phasen des Niedergangs des Reichs von Ur III.”Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie60: 54–69.

Wilkinson, T. J. 2012.

“Introduction to Geography, Climate, Topography and Hydrology.” In: D. T. Potts(ed.),A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Chichester:Blackwell, 3–26.

Winter, I. 1996.

“Sex, Rhetoric and the Public Monument: Τhe Alluring Βody of Naram-Sîn of Agade.” In: N. B. Kampen and B. Bergmann (eds.),Sexuality in Ancient Art: Near East, Egypt, Greece and Italy.Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, 11–26.

Wittfogel, K. A. 1957.

Oriental Despotism. A Comparative Study of Total Power.New Haven &London: Yale University Press.

Yoffee, N. 2005.

Myths of the Archaic State. Evolution of the Earliest Cities, States, and Civilisations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.