Clinic-pathological features of metabolic associated fatty liver disease with hepatitis B virus infection

2021-02-05MingFangWangBoWanYinLianWuJiaoFengHuangYueYongZhuYouBingLi

Ming-Fang Wang, Bo Wan, Yin-Lian Wu, Jiao-Feng Huang, Yue-Yong Zhu, You-Bing Li

Abstract

Key Words: Fatty liver disease; Metabolic associated fatty liver disease; Hepatitis B virus; Biopsy; Clinic-pathological features

INTRODUCTION

Fatty liver disease is one of the most common chronic liver diseases, affecting nearly 25% of the population worldwide[1]. Metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is a new definition proposed recently that is different from previous diagnostic criteria for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)[2,3]. The significant difference between NAFLD and MAFLD is that the diagnosis of MAFLD does not need to exclude other etiology of liver disease, such as excessive alcohol intake or viral infection[4], while the presence of metabolic dysfunction is necessary for MAFLD[5]. These criteria help to identify more cases at high risk[6,7].

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is prevalent in Asia. In China, the HBV infection rate is as high as 5%-6% in the general population[8]. The association between NAFLD and HBV has been controversial for a long time because, theoretically, the diagnosis of NAFLD requires the exclusion of HBV infection[9]. As the MAFLD criteria do not need to exclude chronic hepatitis B, there would be a considerable number of HBV-infected cases diagnosed with MAFLD. In the light of the MAFLD definition, the combination of HBV and MAFLD (HBV-MAFLD) would become an important subtype of MAFLD. The clinicopathological characteristics of this subtype are unclear. To answer this question, this study compared patients with MAFLD and HBV-MAFLD in a large biopsy proven cohort, aiming to characterize MAFLD patients infected with HBV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

This study included a consecutive cohort of patients with pathologically proven steatosis from the Liver Research Center of the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University from 2005 to 2015. The inclusion criteria were meeting MAFLD diagnostic criteria irrespective of HBV infection.

Patients with excessive alcohol intake (male < 40 g/d or female < 20 g/d) were diagnosed with alcoholic liver disease[10], and they were advised to stop consuming alcohol. None of them received liver biopsy in our department. Thus, this study did not include any case with excessive alcohol consumption.

Diagnostic criteria

MAFLD is diagnosed based on histopathologically proven liver steatosis and the presence of one of the following: Overweight or obesity, diabetes mellitus, or evidence of metabolic dysregulation[5]. Overweight was defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥ 23 kg/m2for Asians. The metabolic dysregulation was diagnosed when two of the following criteria were met: (1) Waist circumference ≥ 90/80 cm in Asian men and women; (2) Triglyceride ≥ 1.70 mmoL/L or receiving specific drug treatment; (3) Blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or specific drug treatment; (4) High-density lipoprotein cholesterol < 1.0 mmoL/L for men and < 1.3 mmoL/L for women; (5) Prediabetes [i.e.glycated hemoglobin 5.7%-6.4%, fasting glucose levels (FPG) 5.6 to 6.9 mmoL/L, or 2 h glucose levels 7.8 to 11.0 mmoL/L]; (6) Hypersensitive C-reactive protein level > 2 mg/L; and (7) Homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistance score ≥ 2.5.

Patients were divided into two groups according to the result of HBV surface antigen (HBsAg): MAFLD group (HBsAg negative) and HBV-MAFLD group (HBsAg positive).

Liver biopsy

Liver biopsy was performed with a 16 g Tru-Cut biopsy needle under the guidance of ultrasound. Specimens of 15-20 mm liver tissues were fixed with 10% neutral formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 4 μm slices by Ultra-Thin Semiautomatic Microtome. All slides were stained with hematoxylin-eosin-safran and Masson’s trichrome. Qualified samples were those with a minimum of six portal tracts. All pathology slides were reviewed by two independent pathologists blind to the clinical history. The stages of liver inflammation and the degree of fibrosis were graded in accordance with the Chinese Guidelines of the Programme of Prevention and Cure for Viral Hepatitis[11]. According to the amount of fat accumulation in the hepatocyte, hepatic steatosis can be classified into four grades: S0 (< 5%), S1 (5%-33%), S2 (33%-66%), S3 (> 66%)[12].

Demographic and laboratory parameters

The following variables were obtained from the clinical records: Sex, age, BMI, and history of hypertension and diabetes. BMI was calculated as weight divided by the square of the height.

Biochemical measurements included alanine transaminase, aspartate aminotransferase, γ-glutamyl transferase, FPG, apolipoprotein A, apolipoprotein B, lowdensity lipoprotein cholesterol, very low density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglyceride, total cholesterol, free fatty acids, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and uric acid. Those assessments were detected by AU2700 automatic biochemical instrument of Olympus Company (Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as percentages and continuous variables are expressed as means ± standard deviation. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used for variables that were non-normally distributed; the student t-test was used for the comparison of variables that were normally distributed; and the Chi-squared test was used for categorical variables. Propensity score matching (PSM) was used to balance the age and gender between the two groups with a ratio of 1:1 and a caliper value of 0.2. Logistic regression analysis was used to investigate odds ratio (OR) of HBV infection for liver inflammation, steatosis, and fibrosis. All tests were two-tailed, and results withPvalue less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed with SPSS software (version 24.0, Armonk, NY, United States).

Ethics

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

RESULTS

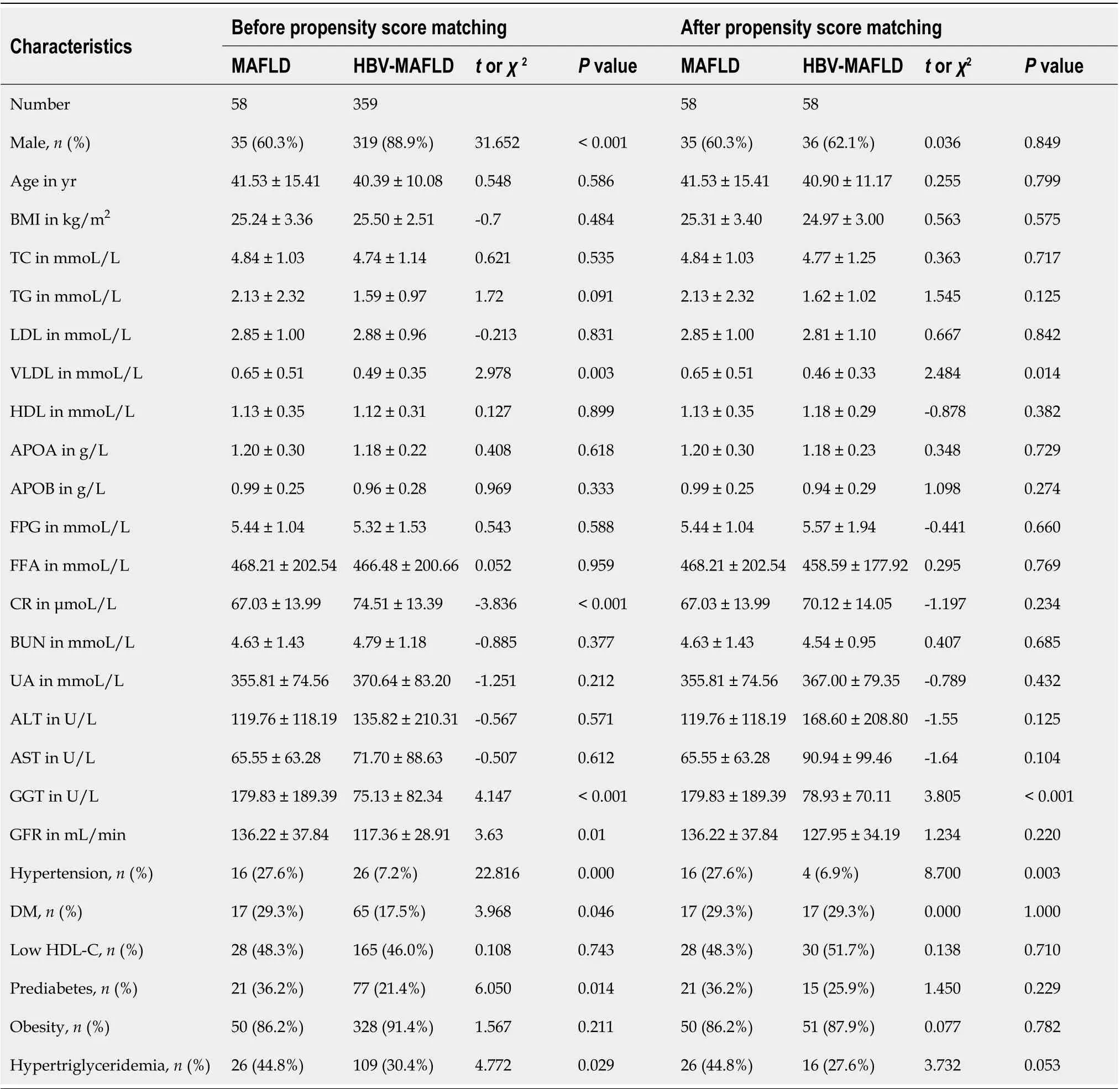

This study included 417 patients with MAFLD, 354 (84.9%) of whom were male, and the average age of this study cohort was 40.5 ± 10.9-years-old. The majority of the cases were infected with HBV (359/417, 86.1%), among whom 184 (51.3%) were HBeAg positive. The average HBVDNA level was 5.69 ± 1.57 Lg IU/mL in the HBVMAFLD group (Table 1).

There were more males in the HBV-MAFLD group than in the MAFLD group (88.9%vs60.3%,P< 0.001). No significant difference was found in BMI, lipids, liver enzymes, and FPG levels between the MAFLD and HBV-MAFLD groups (P> 0.05). However, the proportions of hypertriglyceridemia, pre-diabetes, diabetes, and hypertension were higher in the MAFLD group than in the HBV-MAFLD group (P< 0.05).

After PSM, 58 pairs were successfully matched with no significant differences found in gender and age between the two groups (Table 1). The percentage of hypertension in the MAFLD group was still significantly higher than that in HBV-MAFLD group (27.6%vs6.9%,P< 0.05). The BMI, lipid levels, liver enzymes, and the other metabolic associated comorbidities were comparable between two groups (P> 0.05).

Comparison of liver pathology between MAFLD and HBV-MAFLD

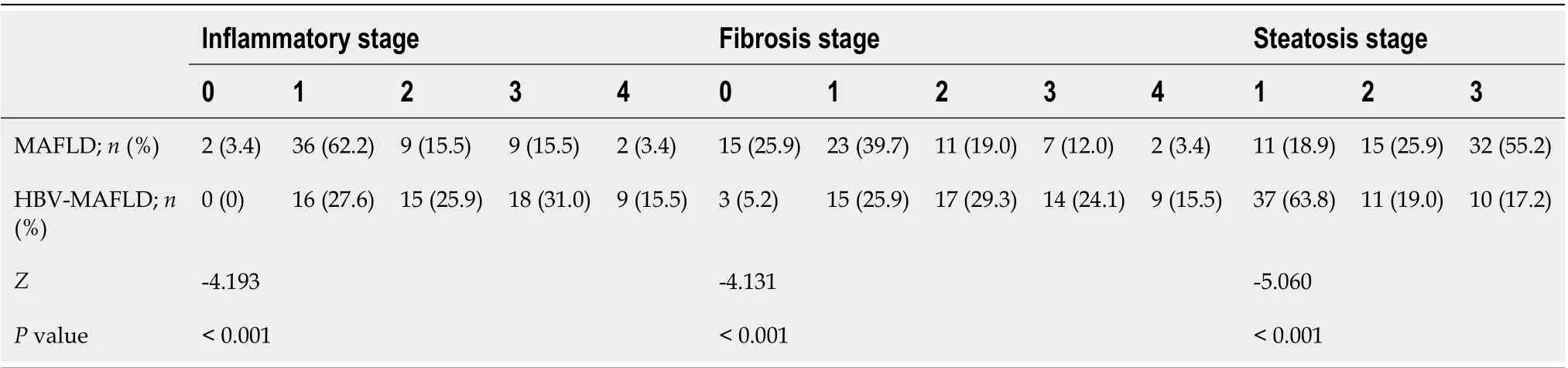

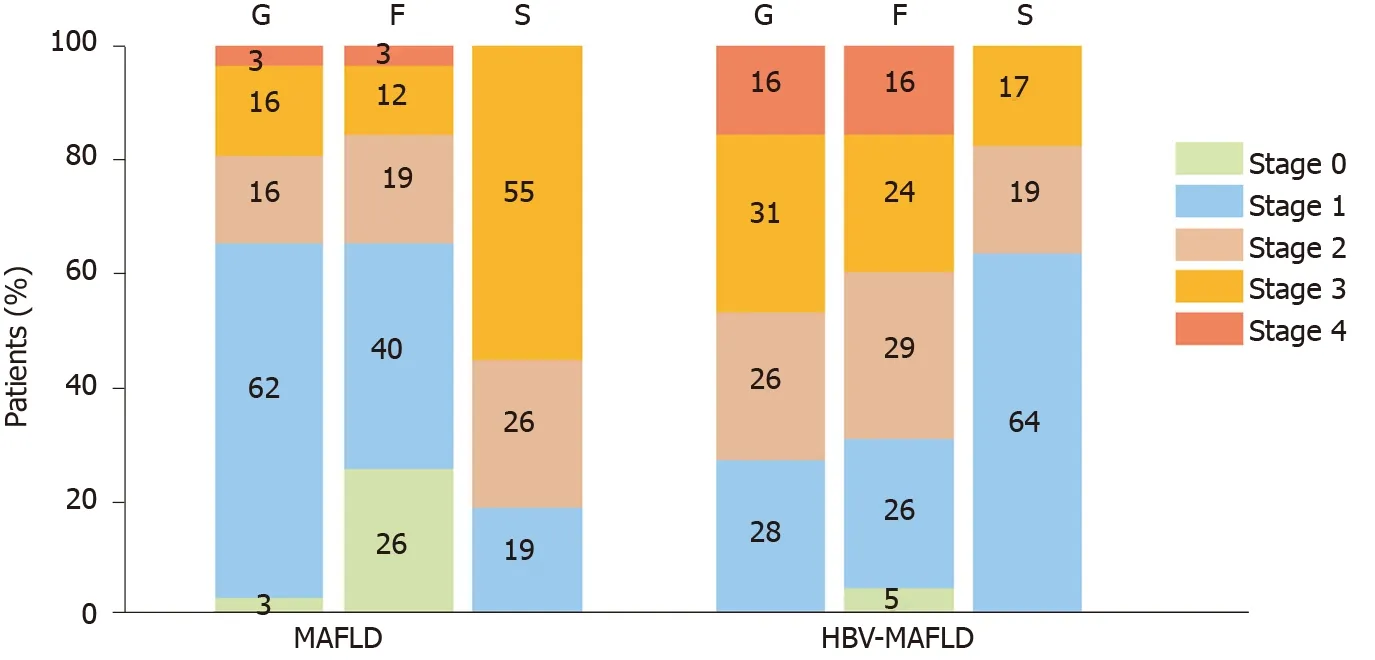

After PSM, there were 10 (17.2%) cases with severe steatosis (S3) in the HBV-MAFLD group and 32 (55.2%) cases in the MAFLD group. The average rank of liver steatosis in the HBV-MAFLD group was 43.76, while that in MAFLD group was 73.24 (P< 0.05), suggesting that liver steatosis in the HBV-MAFLD group was less severe than that in MAFLD group (Figure 1 and Table 2).

There were 27 (46.6%) cases with severe inflammation (G3-4) in the HBV-MAFLD group and 11 (19.0%) cases in the MAFLD group. The average rank of liver inflammation degree in HBV-MAFLD group was 70.84, while that in MAFLD group was 46.16 (P< 0.05). This suggested that the liver inflammation in HBV-MAFLD group was more severe than that in MAFLD group (Figure 2 and Table 2).

Advanced fibrosis (F3-4) was observed in 23 (39.7%) cases in the HBV-MAFLD group and nine (15.5%) cases in the MAFLD group. The fibrosis was more severe in HBV-MAFLD group than that in MAFLD group (average ranks: 71.01vs45.99,P< 0.05) (Table 2).

The Spearman analysis showed in the MAFLD group that the fibrosis and inflammation were positively correlated (r= 0.757,P< 0.001), while the correlation between fibrosis and steatosis was not statistically significant (r= 0.209,P= 0.115). Same results were found in the HBV-MAFLD group (r= 0.696 for fibrosis and inflammation,P< 0.001, andr= -0.002 for fibrosis and steatosis,P= 0.990).

Impact of HBV infection for the severity of steatosis, inflammation, and steatosis in MAFLD

Multivariate analysis was used to explore the impact of HBV infection for the severity of steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis. Two different models were utilized to estimate the OR for different outcomes. Model 1 adjusted for the age and gender, while model 2 additionally adjusted for metabolic parameters including BMI, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, lipid levels, glucose level, and free fatty acids. The results showed that, HBV infection was associated with lower grade of hepatic steatosis (OR 0.088-0.157,P< 0.001) but higher grade of inflammation (OR 4.087-4.059,P< 0.01) and fibrosis (OR 3.016-3.659,P< 0.05) in every model (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

MAFLD with HBV infection is a special subtype of MAFLD in Asian countries. This study found that the metabolic components are not different between MAFLD cases with or without HBV infection. However, the presence of HBV is associated with lower steatosis grade and higher fibrosis and inflammation grade.

The relationship between liver steatosis and HBV infection is not yet clear.Laboratory data showed HBV X protein induces liver fat deposition by activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, sterol regulatory element binding protein 1, and liver fatty acid binding protein 1[13,14], suggesting the HBV virus itself may lead to liver steatosis. However, a cross-sectional study showed current HBV infection may reduce the risk of NAFLD, but this effect became no longer significant after spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance[15]. Several large sample-sized studies showed a negative correlation between HBsAg and the risk of NAFLD in the future[16,17]. In addition, higher BMI also helps the seroclearance of HBsAg[18]. Consistent with previous studies[19], our results showed that concomitant HBV infection led to a lower degree of steatosis. This suggests the novel definition of MAFLD does not greatly influence the correlation between HBV infection and fatty liver disease; HBV infection is associated with lower degree of steatosis in MAFLD.

Table 1 Comparison of baseline characteristics between metabolic associated fatty liver disease and hepatitis B virus-metabolic associated fatty liver disease groups before and after propensity score matching1

Although HBV was associated with lower degree of steatosis in MAFLD patients,unsurprisingly, HBV infection independently increased the risk of inflammation and fibrosis. HBV-infection in MAFLD increased the odds of advanced fibrosis by at least 3-fold and inflammation by 4-fold. This result was in line with a previous report that HBV infection is an independent risk factor for fibrosis in NAFLD[20]. Therefore, for patients with MAFLD combined with HBV infection, closer monitoring and intervention of both factors are required, as the presence of two pathogenic risks might accelerate disease progression.

Table 2 Comparison of histopathological characteristics between metabolic associated fatty liver disease and hepatitis B virusmetabolic associated fatty liver disease groups

Table 3 Odds ratio of hepatitis B virus infection for the pathological changes in metabolic associated fatty liver disease population

Figure 1 Flow chart of cases selection.

Figure 2 Inflammation, fibrosis, and steatosis stage in metabolic associated fatty liver disease and hepatitis B virus-metabolic associated fatty liver disease groups. F: Fibrosis; S: Steatosis; G: Inflammation; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; MAFLD: Metabolic associated fatty liver disease.

The strength of this study is that, to our knowledge, it is the first to focus on the relationship between MAFLD and HBV infection. As MAFLD is a novel, recently proposed concept and its prevalence will keep increasing in future decades[21], the clarification of the association between MAFLD and HBV is of clinical importance. However, there are some limitations that compromise this study. First, this is a single center study. The lack of waist circumference, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance, and C-reactive protein will lead to some missing cases of MAFLD. Second, this cross-sectional study was unable to determine the causal relationship between HBV infection and MAFLD. Lastly, the study population was relatively lean and had less metabolic syndrome. The conclusions should be validated in other populations with higher prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndromes.

CONCLUSION

In summary, cases with HBV-MAFLD have similar metabolic risks compared to pure MAFLD but are associated with lower steatosis grade and higher inflammation and fibrosis grade in histopathology. More attention should be paid to the monitoring and management of MAFLD with HBV infection.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research conclusions

HBV infection is associated with similar metabolic risks, lower steatosis grade, and higher inflammation and fibrosis grade in MAFLD patients.

Research perspectives

The overall body mass index and the prevalence of metabolic disorder were relatively low in this study cohort. The conclusion should be validated in other populations with more metabolic dysfunctions.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Pleiotropy within gene variants associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and traits of the hematopoietic system

- Preoperative maximal voluntary ventilation, hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocytes and platelets predict postoperative survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Effect of remote ischemic preconditioning among donors and recipients following pediatric liver transplantation: A randomized clinical trial

- Could saline irrigation clear all residual common bile duct stones after lithotripsy? A self-controlled prospective cohort study

- Duplication of the common bile duct manifesting as recurrent pyogenic cholangitis: A case report