Tuberous sclerosis patient with neuroendocrine carcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: A case report

2021-01-15NatsukiIshidaTakahiroMiyazuSatoshiTamuraSatoshiSuzukiShinyaTaniMihokoYamadeMoriyaIwaizumiSatoshiOsawaYasushiHamayaKazuyaShinmuraHaruhikoSugimuraKatsutoshiMiuraTakahisaFurutaKenSugimoto

Natsuki Ishida, Takahiro Miyazu, Satoshi Tamura, Satoshi Suzuki, Shinya Tani, Mihoko Yamade, Moriya Iwaizumi, Satoshi Osawa, Yasushi Hamaya, Kazuya Shinmura, Haruhiko Sugimura, Katsutoshi Miura, Takahisa Furuta, Ken Sugimoto

Abstract

Key Words: Tuberous sclerosis complex; Neuroendocrine carcinoma; Neuroendocrine tumor; mTOR inhibitor; Esophagogastric junction; Chemotherapy; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a rare, dominant inherited disease with noncancerous tumor growths in the skin, brain, kidneys, heart, and lungs, and it is caused by abnormalities in the tumor suppressor genes,TSC1andTSC2[1].TSC1andTSC2produce proteins that regulate the intracellular mTOR pathway activity, and the loss of mTOR regulation owing to the abnormalities in these genes is thought to cause many of the symptoms of TSC. In addition, the mTOR pathway is significantly involved in the development of neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), and the mTOR inhibitor, everolimus, is known to be a therapeutic agent for NET[2].

Neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) is a subtype of neuroendocrine neoplasm (NEN), and NEC in the digestive tract is rare. Furthermore, NEC that occurs in the esophagus accounts for only 0.4% of all esophageal carcinomas[3]. There are quite a few detailed case reports regarding NEC occurring at the esophagogastric junction, and there are no reported cases of NEC at the esophagogastric junction with TSC as the underlying disease[4-8].

We, therefore, report an extremely rare case of TSC, which is considered to have an abnormality in the mTOR pathway, co-occurring with NEC.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 43-year-old woman visited the emergency room of our hospital complaining of tarry stool and dizziness.

History of present illness

The patient’s symptoms started the previous day before visiting the emergency room.

History of past illness

The patient has a history of TSC, facial angiofibroma, seizure, renal angiofibroma, and lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM). She was administered sirolimus, which is an mTOR inhibitor, for the treatment of LAM.

Physical examination

On physical examination at the time of hospitalization, her heart rate was 113 beats per minute, and her blood pressure was 95/72 mmHg. The liver, spleen, and tumor were not palpable on physical examination.

Laboratory examinations

Laboratory examination revealed decreased hemoglobin levels (12.6 g/dL) and elevated carcinoembryonic antigen (41.2 ng/mL), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (80 pg/mL), and neuron-specific enolase levels (56.0 ng/mL). Pro-gastrin-releasing peptide level was within the normal limits (40.7 pg/mL).

Imaging examinations

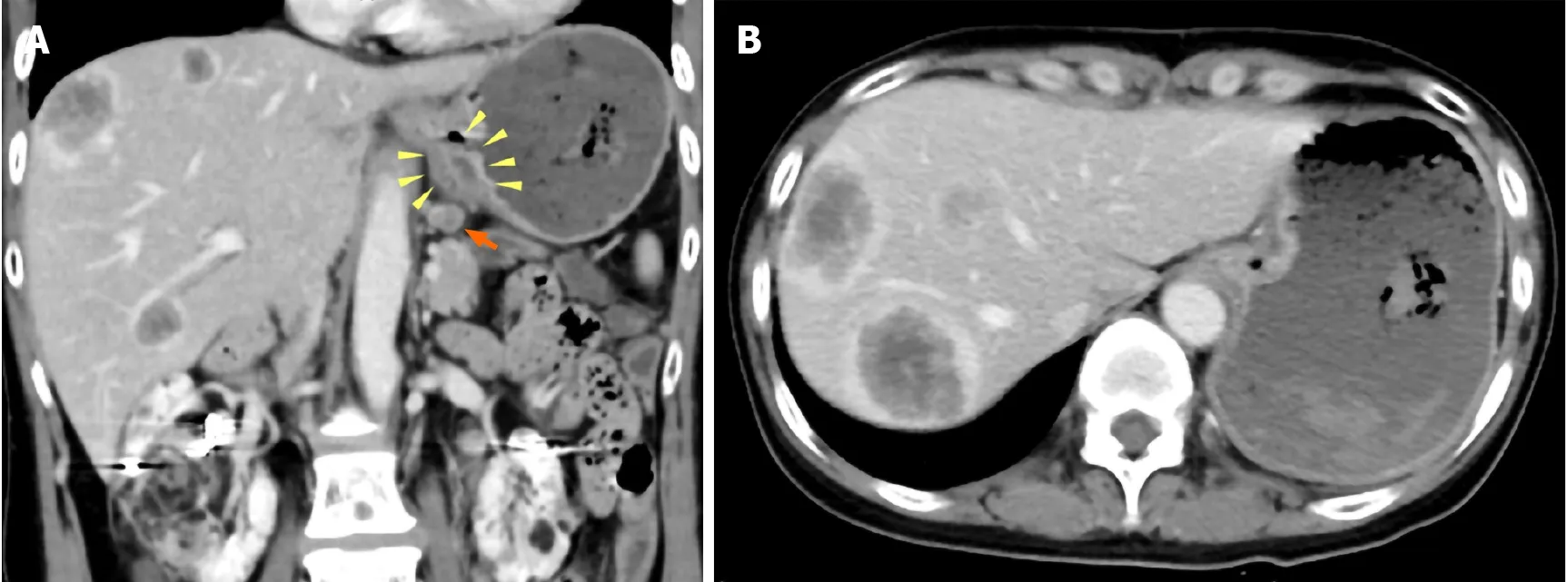

Computed tomography (CT) scans showed wall thickness from the esophagogastric junction to the gastric cardia. Enlarged lymph nodes near the lesser curvature of the stomach and multiple space-occupying, ring-enhancing metastatic lesions in the liver were observed (Figure 1). Gastric endoscopy revealed a type 3 tumor located from the esophagogastric junction to the gastric cardia (Figure 2). The bleeding from the lesion was the cause of the tarry stool, and the patient was then hospitalized and treated with a proton pump inhibitor.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The pathological diagnosis based on a biopsy of a mucosal lesion was NEC (Figure 3). Hematoxylin and eosin (H-E) staining showed atypical epithelial cells forming solid nests with a high nucleocytoplasmic ratio. Tests for immunohistological markers CD56, synaptophysin, and chromogranin A were positive, and the Ki 67 index was approximately 70%. Based on the above results, the patient was diagnosed with esophagogastric neuroendocrine carcinoma T3, N1, M1, Stage IVB (AJCC/UICC 8thedition[9]).

TREATMENT

Since the tumor was clinical stage IV and inoperable, cisplatin (CDDP) + irinotecan (CPT-11) therapy was selected for chemotherapy. The eligible regimen for this patient included cisplatin (60 mg/m2, day 1) and irinotecan (60 mg/m2, day 1, 8, and 15). However, the first cisplatin dose was reduced to 48 mg/m2(80% dose) because of renal failure due to renal angiomyolipoma. The patient experienced grade 2 neutropenia as a side effect after the first course of chemotherapy; irinotecan dose was then reduced to 48 mg/m2(80% dose). A CT scan after seven courses of chemotherapy revealed increased liver metastasis. Serum tumor markers were elevated and disease progression was observed (Figure 4). As a second-line regimen, ramucirumab (RAM) and nab-paclitaxel (nab-PTX) therapy were administered to this patient. The eligible regimen was ramucirumab (8 mg/kg, day 1 and 15) and paclitaxel (80 mg/m2, day 1, 8, and 15). During the eight courses of the second-line chemotherapy, although the patient had no remarkable adverse events, another liver metastasis occurred. Nivolumab was administered as a third-line regimen. However, after one course of treatment, a further increase in tumor markers was observed and liver metastases worsened. As a fourth-line therapy, the S-1 + oxaliplatin regimen was administered to the patient.

Figure 1 Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography images. A: Wall thickness from the esophagogastric junction to the cardia (yellow arrowhead) and enlarged lymph nodes near the lesser curvature of the stomach (orange arrow); B: Multiple ring-enhanced tumors are observed in the liver.

Figure 2 Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed type 3 tumor located from the esophagogastric junction to the cardia. A: Image from endoscopic examination of esophagus; B: Image from endoscopic examination of stomach.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

After two courses of chemotherapy, owing to the exacerbation of NEC, the patient died 23 mo after the first diagnosis. The pathological autopsy was performed with the consent of the patient's family. In addition to multiple liver and lymph node metastases previously identified by CT examination, lung, adrenal, spleen, and kidney metastases, and peritoneal dissemination were observed.

DISCUSSION

The following three points are considered to have high clinical and academic value in this case: (1) NEC co-occurred with TSC, a rare disease; (2) Although the patient was administered sirolimus, an mTOR inhibitor, against LAM, she developed NEC, which is a type of NEN; and (3) The patient was treated with multiple chemotherapy regimens for small-cell lung cancer and gastric cancer, and she survived for 23 mo after the diagnosis.

TSC is an inherited, autosomal, dominant, multisystem disorder characterized by the development of multiple hamartomas in neuron organs. It occurs in 1 in 6000 individuals[10], and approximately 60% of TSCs are sporadic cases. In our case, none of the family members of the patient had TSC. TSC is caused by mutations in two tumor suppressor genes,TSC1on chromosome 9q4 andTSC2on chromosome 16p13.3, which encode hamartin and tuberin, respectively. The mutation type in the patient was not examined. Owing to these gene mutations, TSC may affect the skin, central nervous system, kidney, heart, eye, blood vessels, lung, bone, and gastrointestinal tract. TheTSC1andTSC2genes are involved in the AKT-mTOR pathway activation and are, therefore, involved in the development and proliferation of NETs. Previous studies have reported a relationship between TSC and NETs[11-13]. Gastrointestinal NEC is a type of NEN and is a poorly differentiated cancer with neuroendocrine characteristics classified by the 2019 World Health Organization tumor classification[14]. NEC is known to have a high degree of malignancy and rapid progression. In our case, metastases to various organs were found by pathological autopsy after death.

Figure 3 Histological findings of a mucosal lesion. A: Low-power histological view of Hematoxylin and eosin (H-E) stained specimens showing atypical epithelial cells with solid alveolar nests; B: High-power view of H-E stained specimens reveals poorly differentiated atypical cells with large nucleus-cytoplasm ratio; C: Synaptophysin positive; D: Ki 67 index is approximately 70%; E: CD56 positive; F: Chromogranin A positive.

There are few reported cases on the complications of NETs and TSCs, and there are few reports on the complications of NECs and TSCs. Most of the reported cases of TSCs complicated with NETs have grade 1 or 2 NET[13]. Arvaet al[11]presented a case of well-differentiated NEC of the pancreas in a child with TSC[11]. However, there are no reports of TSC patients with gastrointestinal tract NEC listed in PubMed from 1950 to 2020.

LAM is a rare neoplastic disease in which abnormal LAM cells resembling smooth muscle cells grow relatively slowly in the lungs, lymph nodes, and kidneys. LAM diagnosis is age dependent and occurs in up to 80% of women with TSC by the age of 40[15]. Recently, the effect of the mTOR inhibitor, sirolimus, on LAM was reported[16], and our patient was also administered sirolimus for LAM. In the AKT-mTOR pathway, mTOR inhibitor is thought to reduce protein translation and suppresses subsequent neuroendocrine tumor development (Figure 5)[12]. However, in our case, NEC developed despite the administration of an mTOR inhibitor.

Figure 4 Clinical course of this case. A-D: Serum tumor markers were elevated. A CT scan after seven courses of chemotherapy revealed increased liver metastasis. CDDP: Cisplatin; CPT-11: Irinotecan; RAM: Ramucirumab; nab-PTX: Nab-Paclitaxel; NIVO: Nivolumab; SOX: S-1 and oxaliplatin; CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; CA19-9: Carbohydrate antigen 19-9; NSE: Neuron-specific enolase; Pro-GRP: Pro-gastrin-releasing peptide.

The carcinogenesis of NEC was once argued for the mechanism of stem cell development and development derived from NETs. However, there are genetic differences in NECs that are not observed in NETs such as the overexpression of p53 protein, diffuse deficiency of retinoblastoma protein, and diffuse overexpression of p16 protein in highly malignant tumors. Therefore, NETs and NECs have beenreported to be genetically different[17-19]. In our case, NEC developed while mTOR was inhibited by sirolimus, so it is speculated that this case may have followed the clinical course supported by this theory, because sirolimus could inhibit the development of NEC only if NETs and NECs were genetically similar.

The European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society guidelines recommend that chemotherapy for NEC is based on a small-cell lung cancer regimen[20-21]. The first-line therapy for small-cell lung cancer regimens is CDDP + CPT-11 or CDDP + etoposide (VP16), and retrospective studies in Japan have reported that these platinum-based chemotherapies have equivalent effects for NEC[22]. In our case, the CDDP + CPT-11 regimen, which is frequently administered in Japan, was administered. Since the initial pathological diagnosis suggested that adenocarcinoma might coexist with NETs, chemotherapy of RAM + nab-PTX for adenocarcinoma was selected as the second-line treatment. Although this case was finally diagnosed with NEC, the second-line chemotherapy was successful since the patient was able to continue eight courses of RAM + nab-PTX therapy. Some previous cases have reported the effectiveness of RAM + nab-PTX treatment for gastrointestinal tract NEC[23,24]. In the future, accumulation of RAM + nab-PTX administration cases for gastrointestinal tract NEC is expected.

CONCLUSION

We have reported NEC occurring at the esophagogastric junction in a patient with TSC. Considering the pathogenesis of TSC developed despite the inhibition of the AKT/mTOR pathway, it was a highly suggestive case indicating a difference in the occurrence of NETs and NECs. We also supported the possibility that a RAM + nab-PTX regimen was effective against gastrointestinal NEC.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Chinese guidelines on the management of liver cirrhosis (abbreviated version)

- Altered metabolism of bile acids correlates with clinical parameters and the gut microbiota in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome

- Alteration of fecal tryptophan metabolism correlates with shifted microbiota and may be involved in pathogenesis of colorectal cancer

- Relationship between the incidence of non-hepatic hyperammonemia and the prognosis of patients in the intensive care unit

- Endoscopic mucosal ablation - an alternative treatment for colonic polyps: Three case reports

- Role of pancreatography in the endoscopic management of encapsulated pancreatic collections – review and new proposed classification