Walking-friendly built environments and objectively measured physical function in older adults

2020-12-18MommdJvdKoosrGvnMcCormckTomokNkySbtKorIsAktomoYsunYunLoKocroOk

Mommd Jvd Koosr*,Gvn R.McCormck,Tomok Nky,A Sbt,Kor Is,Aktomo Ysun,Yun Lo,Kocro Ok

aFaculty of Sport Sciences,Waseda University,Tokorozawa 359-1192,Japan bBehavioural Epidemiology Laboratory,Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute,Melbourne,VIC 3004,Australia cMelbourne School of Population and Global Health,The University of Melbourne,Melbourne,VIC 3010,Australia dDepartment of Community Health Sciences,Cumming School of Medicine,University of Calgary,Calgary,Alberta T2N 4Z6,Canada eFaculty of Kinesiology,University of Calgary,Calgary,Alberta T2N 4Z6,Canada fSchool of Architecture,Planning and Landscape,University of Calgary,Calgary,Alberta T2N 4Z6,Canada gGraduate School of Environmental Studies,Tohoku University,Sendai 980-0845,Japan hFaculty of Health and Sport Sciences,University of Tsukuba,Tsukuba 305-8574,Japan iFaculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences,Bunka Gakuen University,Tokyo 151-8523,Japan

Abstract Background:Few studies have examined the associations between urban design attributes and older adults'physical function.Especially,it is not well known how built-environment attributes may in fluence physical function in Asian cities.The aim of this study was to examine associations between objectively measured environmental attributes of walkability and objectively assessed physical function in a sample of Japanese older adults.Methods:Cross-sectional data collected in 2013 from 314 older residents(aged 65-84 years)living in Japan were used.Physical function was estimated from objectively measured upper-and lower-body function,mobility,and balance by a trained research team member.A comprehensive list of built-environment attributes,including population density,availability of destinations,intersection density,and distance to the nearest public transport station,were objectively calculated.Walk Score as a composite measure of neighborhood walkability was also obtained.Results:Among men,higher population density,availability of destinations,and intersection density were significantly associated with better physical function performance(1-legged stance with eyes open).Higher Walk Score was also marginally associated with better physical function performance(1-legged stance with eyes open).None of the environmental attributes were associated with physical function in elderly women.Conclusion:Our findings indicate that environmental attributes of walkability are associated with the physical function of elderly men in the context of Asia.Walking-friendly neighborhoods can not only promote older adults'active behaviors but can also support their physical function.

Keywords:Elderly;Functional test;Neighborhood;Urban design;Walkability

1.Introduction

The world's population is ageing dramatically,and the number of older adults is growing rapidly worldwide.For example,in the United States,88.5 million people will be older than 65 years by 2050.1In Japan,one of every 3 people will be 65 years of age or older by 2036.2Maintaining older adults'physical function is a key factor in supporting their ability to be independent and to age healthfully.3Physical function refers to the ability to perform the basic daily activities,such as eating,bathing,toileting,and dressing,that are required to remain independent.4There is wellestablished evidence of the positive role of physical activity(PA)on physical function in the elderly.5,6For example,a longitudinal study found that PA over the life course was associated with less physical function decline in older adults.7

Older adults'physical function gradually declines with age,so their immediate surrounding environments,such as home and neighborhood,play an important role in supporting their physical function,mainly by providing opportunities for them to remain physically active.8The hypothesis is that walkable environments can positively impact older adults'physical function by providing more opportunities to be physically active.A growing body of research has examined the builtenvironment correlates of older adults'PA.A recent systematic review using a meta-analysis reported strong associations between a neighborhood's physical attributes,such as residential density,walkability,street connectivity,and availability of destinations,with older adults'active movements.9There are few studies,however,examining how these environmental attributes of walkability may in fluence older adults'physical function.10-17For example,a study conducted in the United States found that perceived neighborhood problems(e.g.,noise,traffic,poor lighting)were associated with physical function decline over 1 year.10A longitudinal study conducted in the United Kingdom found that better access to and availability of green spaces was associated with slower decline in physical function among the elderly.13Another recent study found that living in higher walkability areas was negatively associated with functional disability among older adults in Brazil.17

Notably,the majority of these studies were conducted in the context of Western cities in the UK and US.It is less well known how built-environment attributes may in fluence physical function in Asian cities,especially in Japan.As a super-aged society,creating healthful cities that support aging in place for older people has become an ongoing focus in Japan.18However,the lack of evidence-based information regarding walking-friendly neighborhood design in the context of ageing societies is a key challenge.18Similar to many Asian cities,Japanese cities are highly populated and dense.These unique urban-form characteristics are the reasons that the results of previous studies investigating associations between built-environment attributes and physical function conducted in Western countries may not be fully applicable to Asian cities.Evidence from Asia has global relevance and will be of interest to policymakers,population/public health practitioners,and researchers,especially those interested in supporting physical function among older adults in densely populated,compact cities.

Therefore,the current study aimed to examine associations between objectively measured environmental attributes of walkability and objectively assessed physical function in a sample of Japanese older adults.

2.Methods

2.1.Data source and sample

Data were obtained from a larger epidemiologic study conducted in 2013 at Waseda University;it examined social and built-environment determinants of Japanese older adults'health behaviors and outcomes.A detailed description of the sample design and data collection are provided elsewhere.19,20Brie fly,data were obtained from older adult residents living in Matsudo City,Chiba prefecture,Japan.To recruit participants,an invitation letter was sent to 3000 older adult residents(aged 65-84 years)who were randomly selected from the government registry of residential addresses of 107,928 older adults.Of these,a total of 951(31.7%)took part in the main study,and 349(36.7%)participated in a 2-h on-site examination in which health outcomes(e.g.,physical function,body mass index)were collected objectively.A book voucher(JPY1000)was given to those participants who completed the on-site examination.All participants provided written informed consent.The Institutional Ethics Committee of Waseda University(2013-265)and the Institutional Review Board of Chiba Prefectural University of Health Sciences(2012-042)approved the study.

2.2.Measures

2.2.1.Physical function

A trained research team member assessed physical function by using objective measures of upper-and lower-body function,mobility,and balance.Upper-body function was measured by using a hand-grip strength evaluation.Grip strength is a valid indicator of overall health,including physical function in older adults.21,22To measure hand-grip strength,participants stood upright and squeezed,as hard as possible,a Smedley-type handgrip dynamometer(TKK5041,Takei Scientific Instruments,Niigata,Japan)with the grip size adjusted to a comfortable level.23Participants performed 1 trial with the dominant hand(to the nearest 0.1 kg).Lower-body function was measured by maximum gait speed.24The maximum gait speed was measured over an 11-m walkway course starting when the body trunk passed the 3-m mark and ending when the body trunk passed the 8-m mark.Maximum gait speed was measured once and calculated as distance divided by walking time(m/s;to the nearest 0.1 m/s).The timed upand-go test was used to measure mobility.25The timed upand-go was evaluated by asking participants to stand up from an armless chair,walk on a flat surface a distance of 3 m as fast as possible,and return to the chair and sit.The timed upand-go was conducted twice,and the faster of the 2 results(to the nearest 0.1 s)was used.Balance was assessed using a 1-legged stance test with eyes open.Participants raise 1 preferred leg and stand as long as possible.They were timed until they lost their balance or reached a maximum of 60 s.Participants did 2 trials,and the longer of the 2 results(to the nearest 0.1 s)was recorded.

2.2.2.Environmental attributes of walkability

A comprehensive list of environmental attributes,including population density,availability of destinations,intersection density,and distance to the nearest public transport station,that are associated with older adults'PA26,27were included in this study.These attributes were calculated by using geographic information systems software in both 800 m(0.5 mile)and 1600 m(1 mile)road network-based buffers around each participant's geocoded residential address.These buffers were chosen in order to be consistent with several previous studies examining associations between built-environment attributes and older adults'health.28-31Population density was defined as the density of each buffer area(excluding water and no-population zones)using the 500-m gridded population data from the 2010 Japanese population census in the format of Half Grid Square,which is a type of small area unit commonly used for various national statistics in Japan(https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/mesh/06.html).The availability of destinations referred to the total number of 9 types of destinations—banks,bookstores,convenience stores,elementary schools,community centers,postoffices,restaurants,supermarket/department stores,and sports/ fitness clubs—calculated within each buffer.Geographic information systems-based location information of the public facilities is available in the 2010-2013 National Land Numerical Information,which is maintained as open data by the Ministry of Land,Infrastructure,Transport and Tourism(http://nlftp.mlit.go.jp/ksj-e/index.html).The location information of private destinations were obtained by geocoding their addresses as listed in the digitized version of Hello Page,which is a telephone directory maintained by Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation.The 2015 telephone directory data and the 2010-2013 National Land Numerical Information were used to calculate the availability of destinations.Intersection density was measured as the ratio of 3-way or more intersections per km2by using data from the 2015 Digital Maps(Basic Geospatial Information),which comprise geographic information systems vector datasets created and updated by the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan(https://www.gsi.go.jp/common/000078705.pdf). The network-based distance was used to calculate the distance between each participant's location and the nearest public transport station.Walk Score,a publicly available tool,was also obtained from its website(www.walkscore.com)as a composite measure of neighborhood walkability.The validity of the Walk Score as an objective composite measure of neighborhood walkability in Japan has been reported elsewhere.32Walk Score takes into account the access to a variety of destinations,residential density,and street connectivity around any given address.Higher Walk Scores indicate the potential of a location to be conducive to walking.

2.2.3.Covariates

As part of the on-site examination,participants were asked to answerself-administered questionnaires that included sociodemographic information,length of residence,and measures of lower body pain,depression,and cognitive function.Participants reported the following sociodemographic characteristics:age,gender,educational attainment(tertiary or higher,below tertiary),living status(alone,with others),and working status(working with income,retired).Participants were also asked about their lower-body pain using a 1-4 scale(1=no pain,2=mild,3=moderate,and 4=severe)and length of residence in the same house(as a proxy for exposure to the built environment).Depression was measured using the Japanese version of the 15-item Geriatric Depression scale.33,34Cognitive function was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination.35

2.3.Statistical analysis

Theassociations amongenvironmentalattributes of walkability(continuously)and objectively assessed physical function measures were examined by multiple linear regression with adjustment for covariates(age,educational attainment,living status,working status,lower-body pain,length of residence,depression,and cognitive function)stratified by gender.PA is a potential mediator between the built-environment attributes and physical function,so those who were unable to engage in PA were removed from the analysis.Furthermore,each environmental attribute was examined separately in each model(not mutually adjusted because of collinearity)to examine their total effects.Analyses were conducted using Stata 15.0(Stata Corp.,College Station,TX,USA),and the level of significance was set atp<0.05.

3.Results

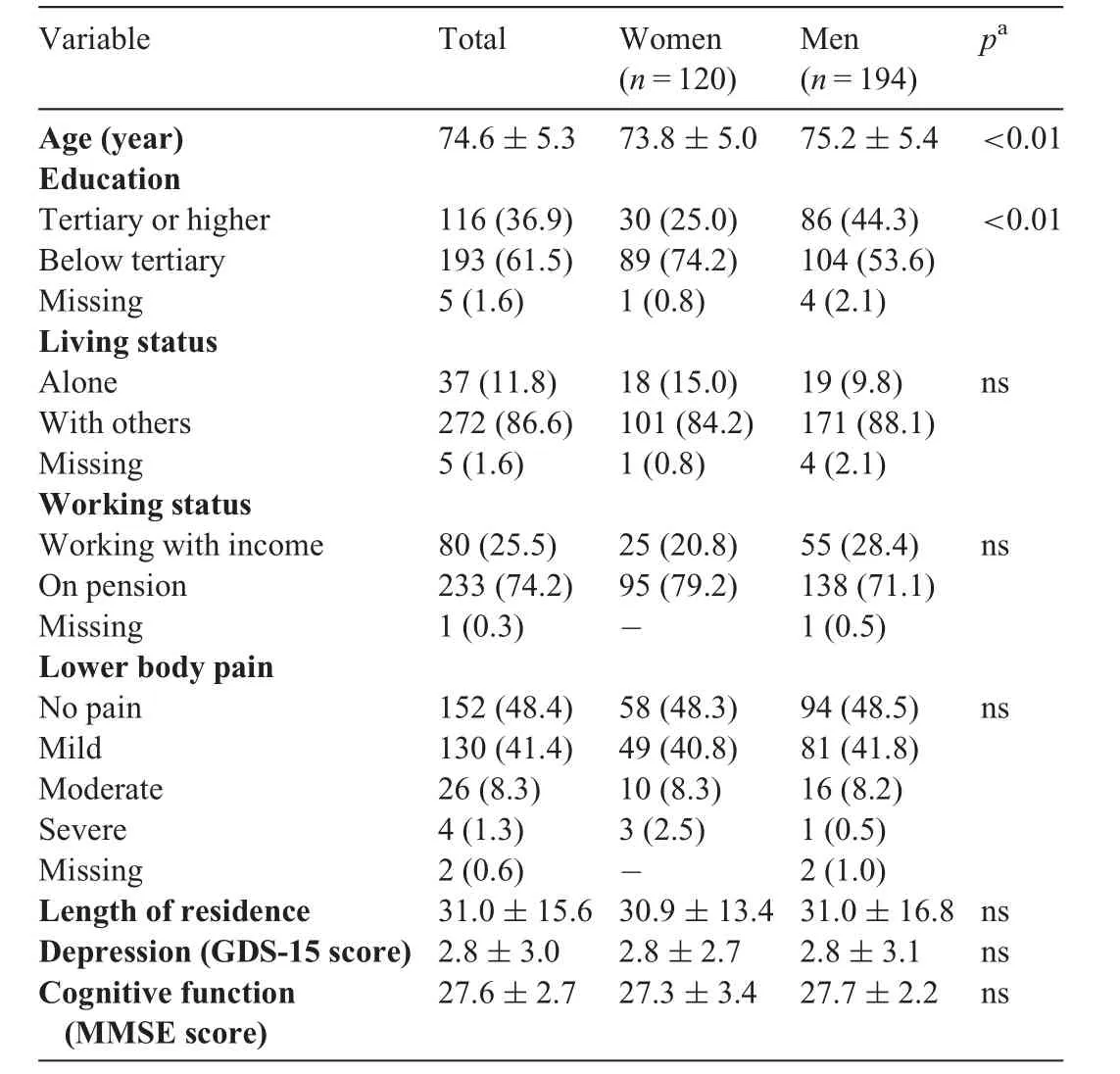

After excluding those with missing physical function values and those who were unable to engage in PA,data from 314 participants were included in this study.Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample.The mean age was 74.6 years,and just over one-third(38.2%)were female,just over onethird(36.9%)had completed tertiary or higher education,86.6%were living with others,more than two-thirds(74.2%)were on pension,and 48.4%had no lower-body pain.In men,the mean age was 75.2 years,and approximately 44.3%had completed a tertiary or higher education.These figures(the mean age and education levels)were lower in women.

Table 1Characteristics of study participants(n=314).

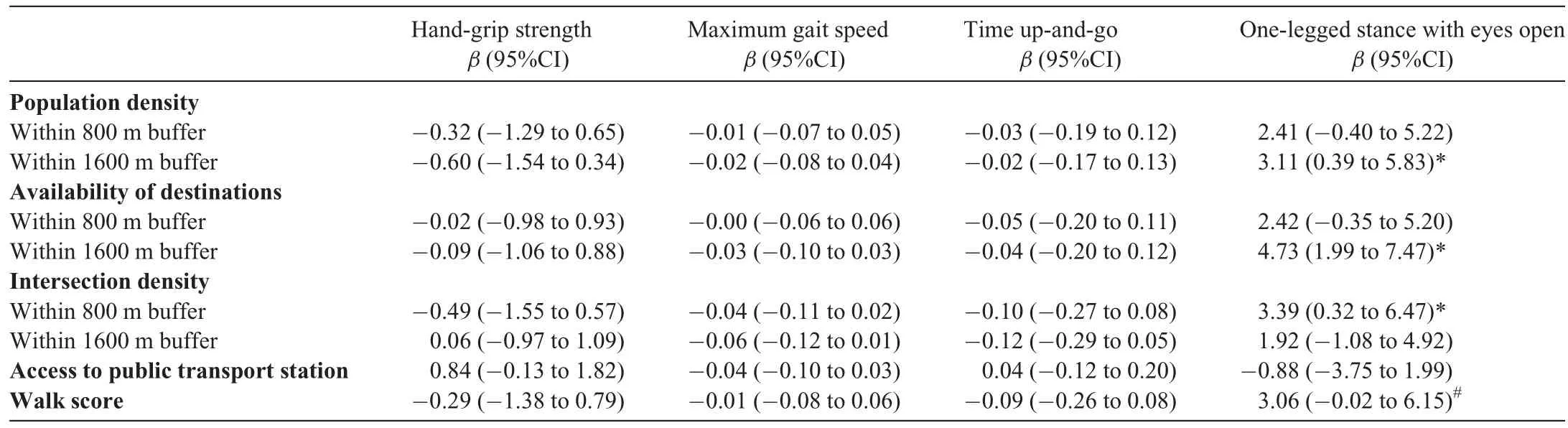

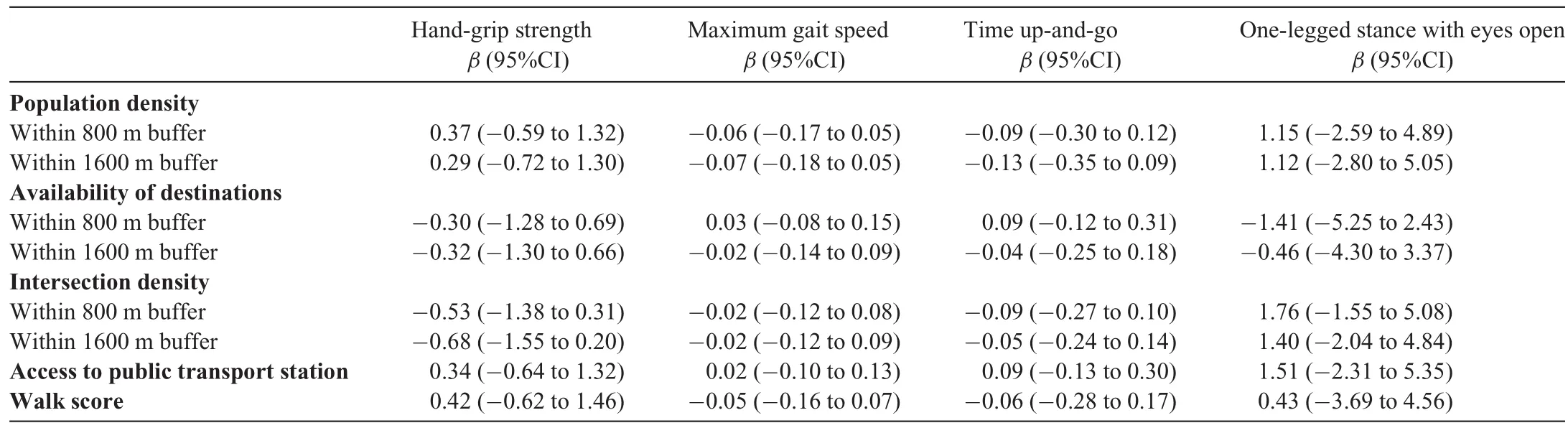

Table 2 and Table 3 show the associations between environmental attributes of walkability and objectively assessed physical function measures,stratified by gender.Most of the physical function outcomes,except the 1-legged stance with eyes open measure,were not significantly associated with environmental attributes of walkability.Among men,there were significant associations among population density within 1600 m(β=3.11,95%CI:0.39-5.83),availability of destinations within 1600 m(β=4.73,95%CI:1.99-7.47),intersection density within 800 m(β=3.39,95%CI:0.32-6.47),and 1-legged stance with eyes open.Walk Score was also marginally significantly associated with 1-legged stance with eyes open(β=3.06,95%CI:-0.02 to 6.15).Among women,none of the environmental attributes were significantly linearly associated with physical-function measures.

4.Discussion

This study examined the associations between walkable environmental attributes and objectively assessed physical function in a sample of older Japanese adults.We found linear positive associations between population density and availability of destinations within a 1600-m buffer,intersection density within 800 m,and Walk Score(marginally significant)with physical function(1-legged stance with eyes open)among men.This finding is consistent with previous findings that have shown associations between walkable environments and older adults'physical function.10,12,14Our study provides unique findings in the context of less-studied Asian cities.There are several pathways through which the walkingfriendly built environment may positively in fluence physical function among older adults.In addition to supporting PA,the environmental attributes of walkability can impact physical function through fostering social interactions.Several studies have shown that residents who lived in walkable environments may have better opportunities to interact with their neighbors and better social engagement,36-38which can positively in fluence their physical function.39,40

Table 2Association between environmental attributes of walkability and objectively assessed physical function measures among men.

Table 3Association between environmental attributes of walkability and objectively assessed physical function measures among women.

Our findings indicate that walkable environments may not be relevant to supporting physical function in elderly women.Previous studies have shown that risk factors for older adults'physical function may differ by gender.41,42For instance,a cross-sectional study found that PA was a strong predictor of physical function among men but not women.41Nevertheless,our results were in contrast with a previous study conducted in the US that found a significant association between neighborhood walkability and a slower decline in physical function among women who engaged in walking.11While Michael et al.'s study11was conducted across 4 metropolitan areas in the US,in a Western sprawl context,our study was conducted in a compact Asian context where environmental attributes,such as population and destinations,are much higher.It is likely that exposure to different levels of environmental attributes may cause these differing results between the 2 studies.Furthermore,it is possible that other aspects of the built environment that were not measured in this study(such as traffic safety or greenery)may be needed to encourage PA in women and in fluence their physical function.Future research from various geographic locations with a comprehensive list of built-environment attributes are needed to identify whether and how environmental attributes may in fluence elderly women's physical function.

Our study had several limitations.As a cross-sectional study,causal relationships between variables cannot be inferred.Data from a relatively healthy sample were used in this study,which may limit the generalizability of our findings.We tested only for linear associations between the built environment and physical function.However,there may be optimal levels above or below which associations between the built environment and physical function differ.This provides urban designers and public health policymakers with more specificcriteria for the optimal number of attributes necessary to in fluence physical function among the elderly.43Future studies from areas with differing amounts of built-environment measures are necessary to examine these optimal values.Furthermore,it is possible that the association between the built environment and physical function is conservative,given that those who were not able to be physically active were excluded,and these individuals may have the lowest or poorest physical function.However,we conceptualized PA as a mediator of the built environment/physical function relationship.Those who are unable to engage in PA were likely not impacted by the features of the built environment associated with walkability.A strength of this study is the use of both objectively assessed built-environment and physical-function attributes.Additionally,2 spatial buffers were used to calculate environmental attributes of walkability,which may better capture residents'activity spaces(compared with using only 1 buffer).

5.Conclusion

The results of this study support the hypothesis that walkability impacts physical function among elderly men.Walking-friendly neighborhoods can not only promote older adults'active behaviors but can also support their physical function.More evidence is needed to explore how walking-friendly neighborhood design,among various geographical contexts,may in fluence older adults'physical function.

Acknowledgments

MJK was supported by the JSPS KAKENHI(#JP15H02964).KO is supported by the MEXT-Supported Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities,2015-2019,the Japan Ministry of Education,Culture,Sports,Science and Technology(S1511017).

Authors’contributions

MJK,GRM,and KO conceived and designed the study,analyzed data,interpreted the findings,and contributed to writing the manuscript;TN,AS,KI,AY,and YL interpreted the findings and contributed to writing the manuscript.All authors contributed to the writing and assisted with the analysis and interpretation.All authors have read and approved the final manuscript,and agree with the order of the presentation of authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.None of the authors has any financial interest in walkscore.com.

杂志排行

Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Isokinetic trunk flexion-extension protocol to assess trunk muscle strength and endurance:Reliability,learning effect,and sex differences

- Effects of compression garments on surface EMG and physiological responses during and after distance running

- Postural control quantification in minimally and moderately impaired persons with multiple sclerosis:The reliability of a posturographic test and its relationships with functional ability

- Residual force enhancement due to active muscle lengthening allows similar reductions in neuromuscular activation during position-and force-control tasks

- Health-related fitness knowledge growth in middle school years:Individual-and school-level correlates

- Habitual physical activity levels and sedentary time of children in different childcare arrangements from a nationally representative sample of Canadian preschoolers