Ischemic colitis after enema administration: Incidence, timing, and clinical features

2020-12-11YuraAhnGilSunHongJuHeeLeeChoongWookLeeSeonOkKim

Yura Ahn, Gil-Sun Hong, Ju Hee Lee, Choong Wook Lee, Seon-Ok Kim

Abstract

Key Words: Enema; Glycerin; Ischemic colitis; Incidence; Timing; Risk factors

INTRODUCTION

Enema administration is a procedure used to stimulate stool evacuation and is generally considered to be safe[1]. It is most commonly performed to relieve severe constipation[2,3]. In addition, it is also used for the treatment of hyperkalemia and hepatic encephalopathy. Enemas function through several different mechanisms. All cleansing enemas induce rectal distension and subsequently stimulate colon contraction and stool elimination[2]. Other enemas such as phosphate enema function by direct stimulation of the muscles of the colon. There are several enema agents: Phosphate, saline, tap water, glycerin, and a synthetic sugar for the cleaning of the colon; and Kalimate for the treatment of hyperkalemia. The elderly are five times more prone to constipation because of the effect of medication, immobility, and a blunted urge to defecate[4]. Many patients usually give themselves enemas at home owing to the availability of over-the-counter medications. However, some patients need urgent care and are referred to the emergency department (ED) for the aforementioned medical conditions. The number of patients referred to the ED for enema administration has increased over time[5]. Given the surge in the elderly population, the number of patients requiring this urgent care in hospitals is expected to rise.

Adverse events after enema administration are rarely reported in the literatures but may cause critical conditions in patients. Enema-related complications include bowel perforation, ischemic colitis (IC), malignant hyperthermia, and colonic mural hematoma[6-10]. In general, IC is known to be transitional or self-limited, but sometimes requires surgical intervention or leads to death especially in the postoperative period[11]. The existence of a relationship between IC and enema administration has been suggested in the literature. Several case reports have reported IC following enema administration for the treatment of constipation, preoperative bowel cleansing and the correction of hyperkalemia[12-15]. Therefore, in some studies, enema administration has been considered to be a risk factor for the development of IC[16,17]. However, despite the popularity of this procedure, there have been no studies to systemically investigate enema-related IC.

The present study aimed to investigate the incidence, timing and risk factors of IC in patients receiving enema.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

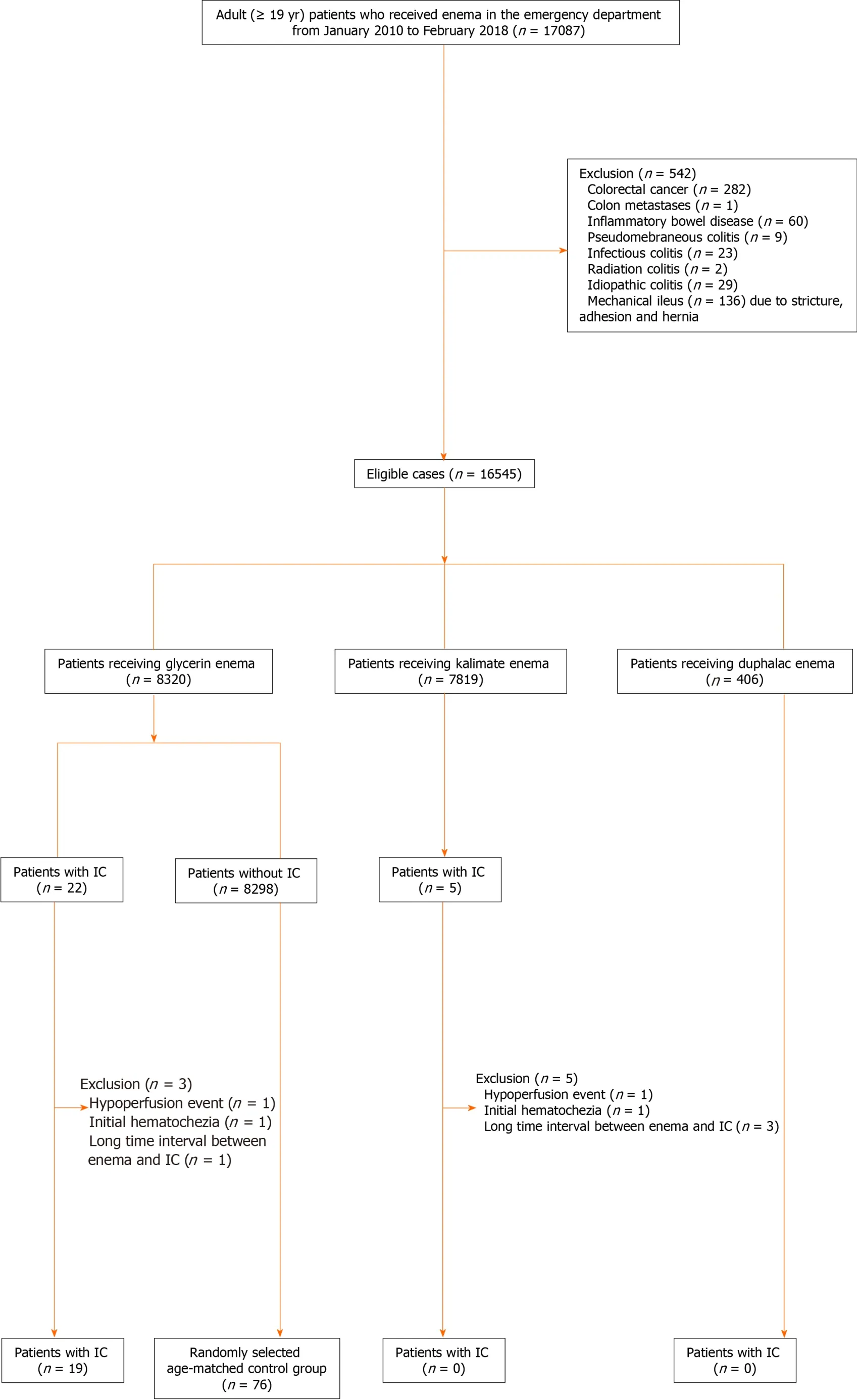

In this retrospective study, we analyzed the data of adult patients with confirmed IC after enema administration in the ED between January 2010 and February 2018. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Adults aged > 19 years; and (2) Patients with confirmed IC after enema administration but without suspected IC symptoms and clinical examination results (e.g., hematochezia, sudden drop in blood pressure, abdominal tenderness, and guarding) before enema. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients with unspecific vascular hypoperfusion or its similar condition (e.g., cardiac failure, septic shock, hemodynamic shock, hemodialysis, and aortic surgery), colonic obstruction (volvulus, adhesion, stricture, hernia, colon cancer, or metastasis), vascular occlusion (based on the findings of follow-up CTs performed after enema), and infectious or inflammatory bowel disease (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, radiation colitis, and infectious colitis); and (2) Time interval from enema administration to IC occurrence of > 24 h based on the prior case reports[13-15]. Among 17087 adult patients receiving enema in the ED, 542 patients were excluded due to infectious or inflammatory bowel disease (n= 123), colonic malignancy (n= 283), and mechanical ileus (n= 136). The remnant patients received one of three types of enema agents: 8320 received glycerin enema (150 g of glycerin in 150 mL of purified water); 7819 received Kalimate enema (calcium polystyrene sulfonate; 30 g of Kalimate in 200 mL of purified water); and 406 received Duphalac enema [300 mL of lactulose solution (composition: 3.335 g lactulose/5 mL)]. After excluding patients with predisposing events, hematochezia, or long-time interval, 19 patients in the glycerin enema group were finally included. For a case-control study with a case to control ratio of 1:4, an age-matched control group was randomly selected from patients receiving glycerin enema. Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the study population.

Clinical and laboratory data

The clinical data included age, sex, age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index (ACCI) score, constipation score, medication, enema agents, time of enema administration, initial symptoms, initial vital signs, and laboratory findings [C-reactive protein (CRP) and white blood cell count (WBC)] at the time before enema administration. The ACCI score was calculated using the algorithm proposed by Charlsonet al[18], in which 19 comorbid conditions were weighted and scored and additional points were added for age. The constipation score was calculated using modified simple criteria based on the Wexner constipation scoring system[19]. Four conditions of these criteria were: History of chronic constipation; recurrent usage of defecation assistance; last defecation ≥ 5 d prior to admission to the ED; unsuccessful evacuation attempts using enema within 24 h. Each condition was scored on a two-point scale (0-1). IC-related medications were classified into two groups — drugs with a moderate evidence level and those with a low evidence level — according to the drugs reported to predispose patients to IC in a previous report[20]. The clinical data on the post-enema administration duration included symptom change, time of a change in symptom or vital signs, diagnostic method, treatment method, and treatment outcome. The radiologic and endoscopic reports were also recorded. In patients diagnosed with IC, bowel preparation was not performed before colonoscopy because of the risk of perforation or toxic dilation. The time of IC occurrence was defined as the time between enema and a change in symptoms and/or vital signs requiring further examination or treatment in the presence of suspicions of IC.

Radiologic examinations

All analytic images were available on a picture archiving and communications system (PACS). Plain abdominal radiographs were routinely performed in all patients before enema administration in the ED. Of the 19 patients diagnosed with IC following glycerin enema administration, 18 received contrast-enhanced abdominopelvic computed tomography (AP-CT) and one underwent non-contrast enhanced AP-CT. All AP-CT images were acquired using a multidetector CT scanner (Somatom Sensation 16 CT scanners, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with or without intravenous contrast material (Ultravist 300 or Ultravist 370; Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin, Germany). AP-CT consisted of a portal phase image with a fixed 60-70 S delay following the injection of intravenous contrast media.

Image analysis

Figure 1 Flow diagram of the study population. IC: Ischemic colitis.

All radiologic images were reviewed by two radiologists (Hong GS and Ahn Y with > 13 years and 4 years of experience in abdominal imaging, respectively) in consensus. Plain abdominal radiographs were reviewed for abnormal gas or abnormal bowel gas patterns except for constipation. The following selected imaging features were reviewed on AP-CT images: Segmental bowel wall thickening [location, bowel wall thickening thickness (one-side wall thickness), wall thickening pattern (circumferential/eccentric), and skip area], decreased bowel wall enhancement [involving layer (no involvement, inner layer, and transmural), target sign, and skip area], mesenteric manifestation (pericolic fluid or fat stranding and peritoneal free fluid or mesenteric edema), pneumatosis coli, portal and/or drain venous gas, pneumoperitoneum, and vascular occlusion.

Statistical analysis

All variables were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Comparisons between the case and control groups were performed using the chi square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Student’st-test or the Mann-WhitneyU-test for continuous variables. Conditional logistic regression was used to identify risk factors associated with IC. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed using backward elimination. Statistical significance was considered when a probability value (Pvalue) was less than 0.05. For all statistical analysis, a commercial software (SPSS, version 23; SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States; and SAS version 9.4; SAS Institute; Cary, NC, United States) was used.

RESULTS

Incidence of IC following enema administration and its clinical outcome

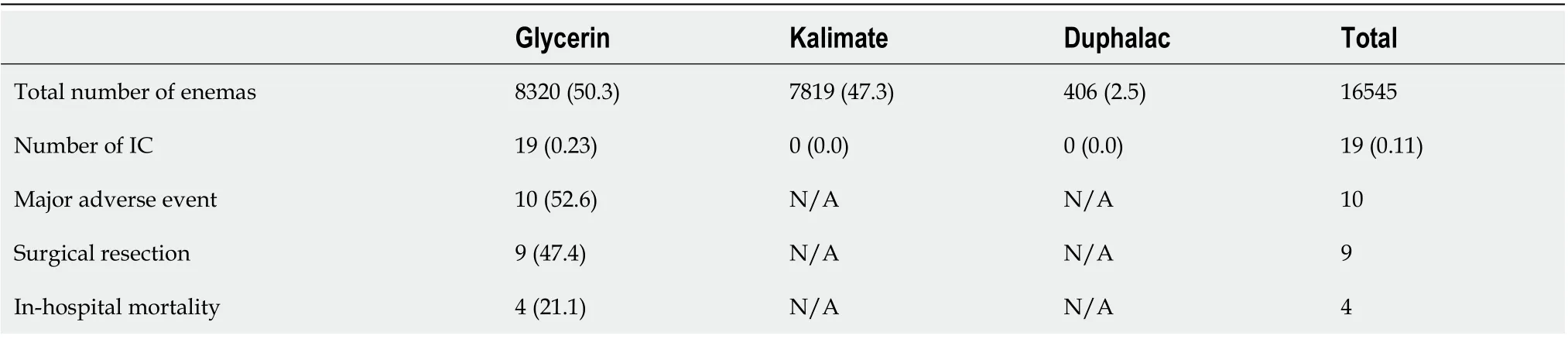

Table 1 shows the incidence of IC following enema administration according to the enema agent used. The incidence of edema-related IC was very low; 0.23 % (19/8320) in the glycerin enema group, but there was no occurrence of IC with the usage of the other enema agents. Major adverse events occurred in 52.6% (10/19) of the patients with glycerin enema-related IC: 47.4% (9/19) requiring surgical resections and 21.1% (4/19) resulting in in-hospital mortality.

反应SiO2(s)+2C(s)==Si(s)+2CO(g)的 ΔH=____kJ·mol-1(用含a、b的代数式表示)。SiO是反应过程中的中间产物。隔绝空气时,SiO与NaOH溶液反应(产物中硅显最高价)的化学方程式是____。

Demographic and clinical characteristics

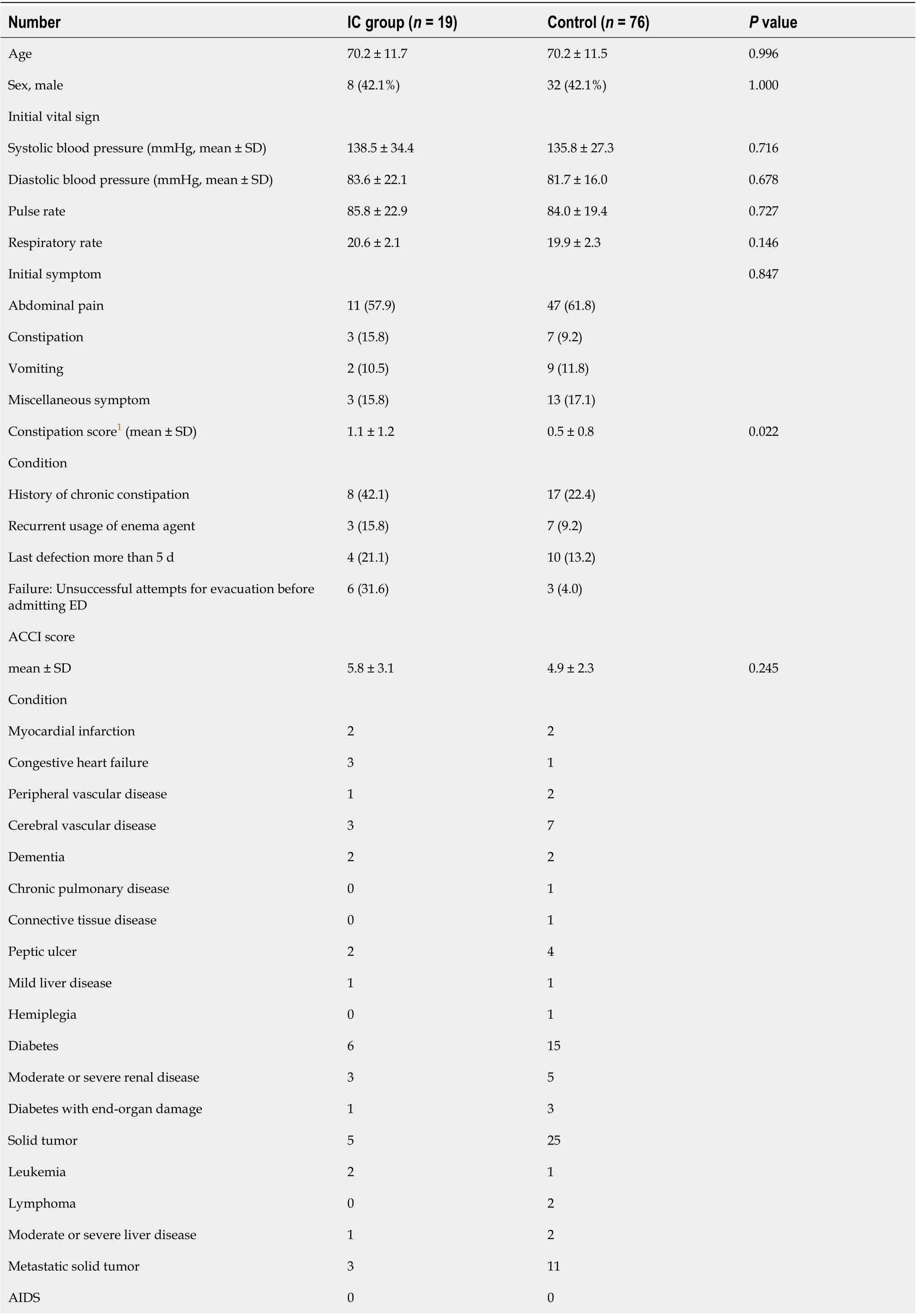

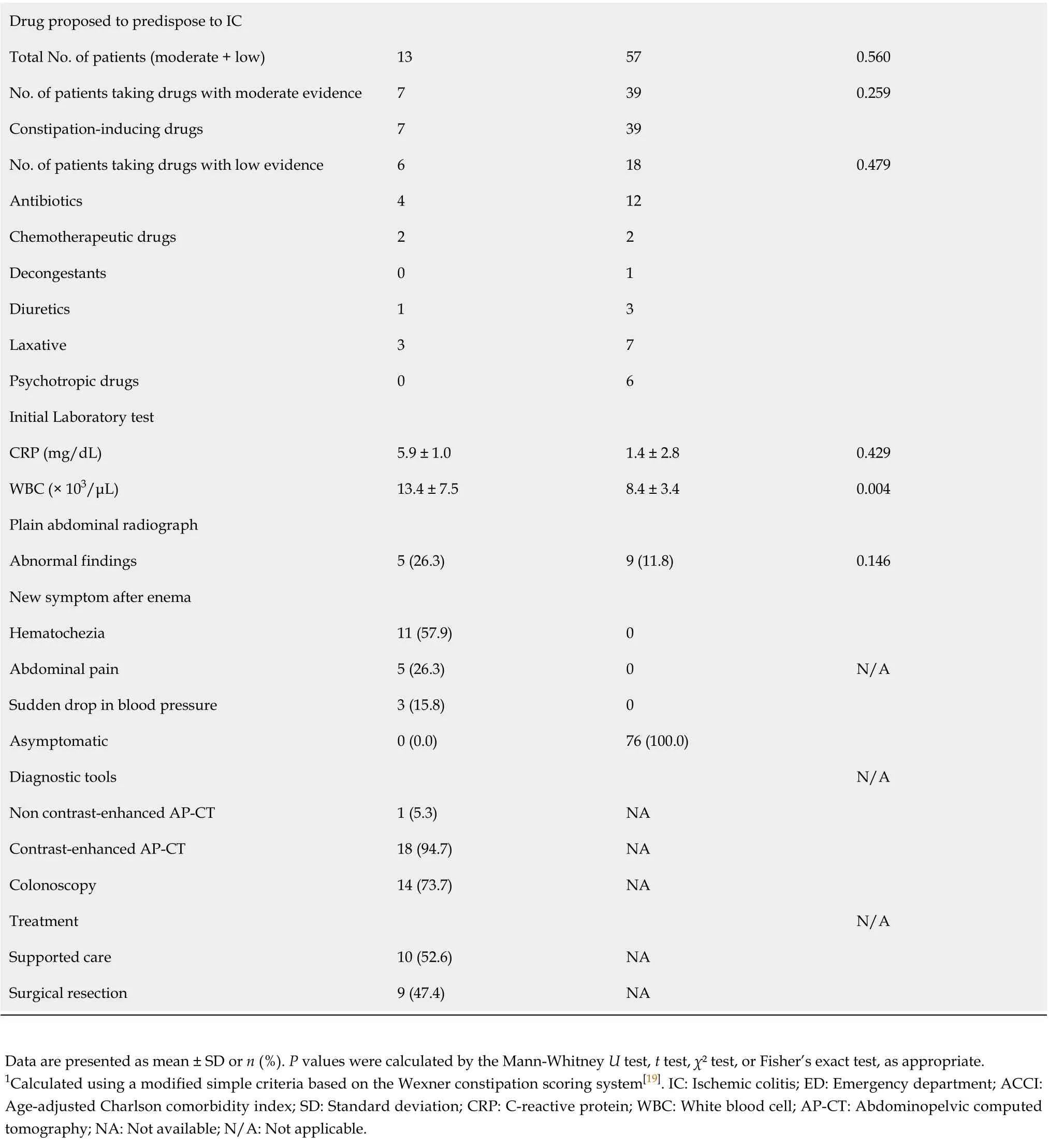

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population were similar between the two groups with or without glycerin enema-related IC (Table 2). Of note, most patients diagnosed with glycerin-related IC were elderly [mean age ± standard deviation (SD), 70.2 ± 11.7 years]. The main initial symptom of the IC group was abdominal pain [57.9%, (11/19)], followed by constipation [15.8%, (3/19)]. There was no significant difference between the IC and non-IC groups in terms of initial vital signs, symptoms, ACCI, and medication. The review of plain abdominal radiographs showed no significant difference between the IC and non-IC groups. There was a statistically significant difference in the constipation score and WBC count between the two groups. Of the 19 patients diagnosed with glycerin-related IC, 8 (42.1%) had a history of chronic constipation, 3 (15.8%) recurrently used defecation assistance, 4 (21.1%) lastly defecated ≥ 5 d prior to admission to the ED, and 6 (31.6%) had a history of evacuation failure using enema within 24 h. In the 19 patients diagnosed with IC, the mean ± standard deviation of WBC count was 13.4 ± 7.5 × 103/μL before enema administration. Of these patients, 16 had available records of their WBC counts immediately after enema. The WBC count (11.6 ± 6.9 × 103/μL) after enema was slightly decreased as compared with that before enema. After the administration of enema, patients with IC mainly presented hematochezia [57.9%, (11/19)], followed by abdominal pain [26.3%, (5/19)] and a sudden drop in blood pressure [15.8%, (3/19)]. The most common diagnostic tool in the emergency department for patients with IC was CT scan [100%, (19/19)] followed by colonoscopy [73.7%, (14/19)]. Less than half the patients with IC received surgical resection [47.4%, (9/19)].

Timing of IC following glycerin enema

Figure 2 shows the time interval between enema administration and IC occurrence. Mean time interval ± SD from glycerin enema administration to IC occurrence was 5.5 h ± 3.9 h (range: 1-15 h). Of the 19 patients, 15 (79.0%) developed IC within 8 h of glycerin enema administration. Of the 11 patients in whom IC occurred within 4 h of glycerin enema administration, 7 (63.6%) underwent surgical resection, whereas of the 8 patients who experienced IC after 4 h, 2 (25%) underwent surgical resection.

Table 1 Incidence of enema-related ischemic colitis and its major adverse events

Risk factors to predict IC following glycerin enema

In the conditional logistic regression analysis, the risk factors for the glycerin-related IC were the constipation score [Odds ratio (OR), 2.0; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.1-3.5,P= 0.017], and leukocytosis (OR, 4.5; 95%CI: 1.4-14.7,P= 0.012) (Table 3).

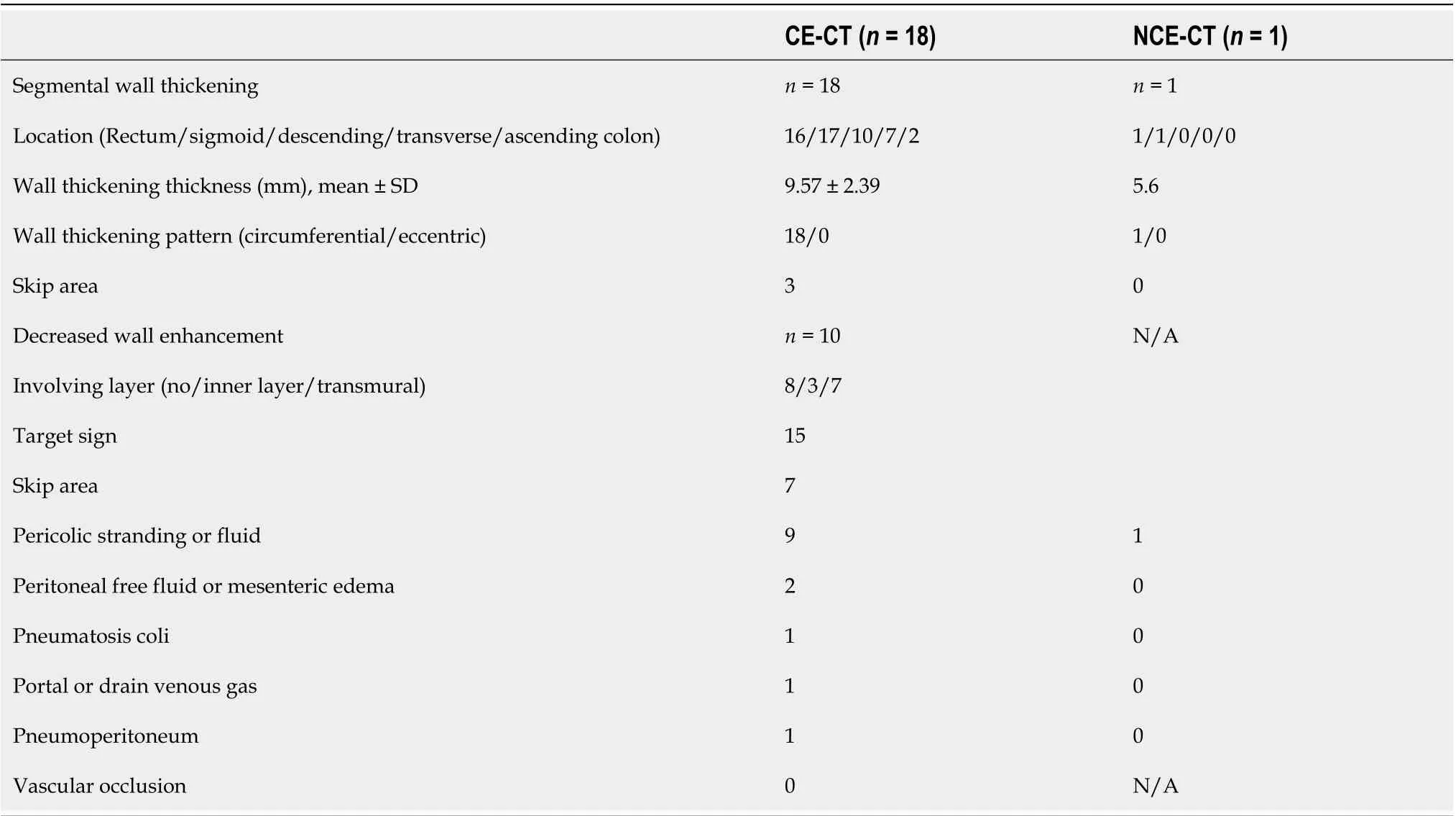

CT features and review of radiology reporting

Table 4 shows the radiologic features on CT in patients. Among the 19 patients diagnosed with glycerin enema-related IC, 18 patients received contrast-enhanced CT scans and one patient was examined with a non-contrast CT scan. In all patients, CT imaging revealed a circumferential wall thickening of the colon. In most cases, colonic wall thickening was continuous except for three cases with a skip area. The colonic wall thickening was located mainly in the rectosigmoid colon [94.7%, (18/19)], followed by the descending colon [52.6%, (10/19)]. In two patients, colonic wall thickening extended to the ascending colon. Among the 18 contrast-enhanced CT images, a decreased wall enhancement was noted in 10 (55.6%) patients (inner layer,n= 3; transmural,n= 7), but not in 8 patients. Of these, 7 (70.0%) patients showed a skip area of the decreased wall enhancement. Pneumatosis colic and portal venous gas were detected in one [5.3%, (1/19)] patient and pneumoperitoneum in one [5.3%, (1/19)] patient. Regardless of the numerous features of IC, vascular occlusion was not noted in contrast-enhanced CT. Of note, misinterpretation occurred in 7 (36.8%) of 19 patients: These diagnoses consisted of stercoral colitis, infectious colitis, and pseudoobstruction.

DISCUSSION

To best our knowledge, there has been no study on a systemic approach of enemarelated IC. Our data suggest a necessity for observation in the early period after enema administration in the elderly with glycerin enema based on the constipation scores and initial laboratory findings.

The present study is the first to investigate the incidence of IC according to enema agent. We showed that the incidence [0.23%, (19/8320)] of glycerin enema-related IC was very low. Nivet al[21]reported that colon perforation after cleansing enema occurred in 1.4% of patients with acute constipation in the ED. However, this is mainly due to the inappropriate positioning of the device tip, even though it might be associated with a localized weakness of the rectal wall. It is known that non-occlusive IC is typically transient, although transmural necrosis can be induced by prolonged non-occlusive ischemia. Approximately 15% of patients with IC progress to gangrenous colitis, resulting in life-threatening conditions[22]. However, in the present study, nearly half of patients with glycerin-related IC received surgical resection for transmural necrosis, and four patients died during hospitalization. This is a higher rate than that reported previously. The higher surgical rate obtained in the present study could be caused by the severe symptoms. However, in all the cases examined, surgical resection was determined not only based on the symptoms but also according to the disease severity assessed by CT and/or colonoscopy findings. In addition, as aforementioned, all the patients who underwent surgical resection were histologically confirmed to have transmural necrosis. Therefore, our data may imply that glycerin enema leads to a relatively severe IC, resulting in a progression to gangrenous colitis. In the present study, we could not define the relationship between Kalimate enema and IC occurrence although all the cases proposed here had crystals with acharacteristic crystalline mosaic pattern on the mucosa and ulcer bed tissue similar to those of previous reports. This may be because the cases proposed here had a medication history of repeated use of Kalimate enema solution or oral Kalimate. In addition, IC occurred at a relatively longer time after the last administration of Kalimate. Therefore, it is difficult to definitely indicate its association with IC occurrence, and further studies are warranted.

Table 2 Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study patients receiving glycerin enema

Drug proposed to predispose to IC Total No. of patients (moderate + low)13 57 0.560 No. of patients taking drugs with moderate evidence 7 39 0.259 Constipation-inducing drugs 7 39 No. of patients taking drugs with low evidence 6 18 0.479 Antibiotics 4 12 Chemotherapeutic drugs 2 2 Decongestants 0 1 Diuretics 1 3 Laxative 3 7 Psychotropic drugs 0 6 Initial Laboratory test CRP (mg/dL)5.9 ± 1.0 1.4 ± 2.8 0.429 WBC (× 103/μL)13.4 ± 7.5 8.4 ± 3.4 0.004 Plain abdominal radiograph Abnormal findings 5 (26.3)9 (11.8)0.146 New symptom after enema Hematochezia 11 (57.9)0 Abdominal pain 5 (26.3)0 N/A Sudden drop in blood pressure 3 (15.8)0 Asymptomatic 0 (0.0)76 (100.0)Diagnostic tools N/A Non contrast-enhanced AP-CT 1 (5.3)NA Contrast-enhanced AP-CT 18 (94.7)NA Colonoscopy 14 (73.7)NA Treatment N/A Supported care 10 (52.6)NA Surgical resection 9 (47.4)NA Data are presented as mean ± SD or n (%). P values were calculated by the Mann-Whitney U test, t test, χ² test, or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.1Calculated using a modified simple criteria based on the Wexner constipation scoring system[19]. IC: Ischemic colitis; ED: Emergency department; ACCI: Age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index; SD: Standard deviation; CRP: C-reactive protein; WBC: White blood cell; AP-CT: Abdominopelvic computed tomography; NA: Not available; N/A: Not applicable.

The eligibility criteria proposed here were based on the clinical conditions (symptoms, signs, and possible etiologies of IC), and not on CT or endoscopy findings. It is mainly because aggressive workup (i.e., CT and colonoscopy) is not usually performed, unless an underlying disease is suspected in patients requiring enema for constipation in the ED. Therefore, existing IC before enema could be overlooked because self-limited or transient IC can often present with vague abdominal symptoms. However, although self-limited or transient IC caused by constipation exists before enema, it is plausible that glycerin enema triggers or aggravates mild IC, considering the high proportion of transmural necrosis in the present study.

Although glycerin enema-related IC rarely occurs, its timing is a notable consideration. Prior studies demonstrated that increased length of stay at the EDcontributes to ED crowding[23]. ED crowding is associated with adverse patient outcomes, including increased mortality[24,25]. Therefore, determining the optimal observation time for this patient group in the ED is important, considering that glycerin enema-related IC is a lethal complication despite its rarity. In the present study, IC occurred in 15 (79.0%) of 19 patients within 8 h of glycerin enema administration. Notably, surgical resection was performed in 7 (63.6%) of 11 patients in whom IC occurred in ≤ 4 h. Based on previous case reports, the time interval between cleansing enema and IC occurrence ranged from 30 min to 6 h. Changet al[13]reported a case wherein IC and hematochezia developed 6 h after glycerin enema for preoperative bowel cleansing for coronary bypass surgery . Parket al[14]reported a case of IC that occurred within 2 h of normal saline enema for preoperative bowel cleansing. Most recently, Yoonet al[15]reported a case of IC that presented abdominal pain and hematochezia within 30 min of enema administration. Our data suggest that it may be necessary to observe patients receiving glycerin enema in the early period after administration (at least 4 to 8 h), considering timing of IC and high surgical resection rates.

Table 3 Conditional regression analysis for the prediction of glycerin enema-related ischemic colitis

Table 4 Radiologic features on computed tomography in patients with ischemic colitis after glycerin enema administration (n = 19)

Figure 2 Time interval from glycerin enema administration to ischemic colitis occurrence. The curve shows the cumulative percentage of patients diagnosed over time with glycerin-related ischemic colitis. IC: Ischemic colitis.

In the current study, it is worth noting that the constipation score was one of the significant independent predictive factors of IC among patients receiving glycerin enema at the ED. We used a modified constipation scoring system to obtain an objective definition of constipation. Prior studies demonstrated that constipation may be one of the predisposing factors for IC[26-30]. The reasonable mechanism for this was advanced by Anonet al[31]: The increased colonic luminal pressure could cause poorer blood flow in the colonic wall. Therefore, in this setting, edema could aggravate the increased intraluminal pressure and cause vascular spasm due to the lower temperature of the enema fluid than the body temperature, resulting in a reduced mucosal circulation. In our study, we also identified leukocytosis as another predisposing factor for glycerin enema-related IC, as shown in other studies on the risk factors of IC[30,32]. Leukocytosis is a common sign of infection, but not a definitive marker of significant infection. Reactive leukocytosis can occur because of various etiologies, including constipation. Obokhare[33]showed that constipation and fecal impaction can mildly elevate the WBC count. In the present study, the WBC count after enema was slightly lower than that before enema. In addition, none of the patients showed any signs and symptoms of infection. Therefore, leukocytosis may be associated with chronic constipation. According to a prior study, leukocytosis may imply the presence of transient IC in patients with chronic constipation. In conclusion, leukocytosis is not a specific clinical marker of IC but may be associated with chronic constipation or transient IC. Regardless of its cause, in older patients with leukocytosis and chronic constipation, glycerin enema may trigger or induce a relatively severe ischemic colitis. However, in clinical practice, these conditions (i.e., high constipation score and leukocytosis) predisposing to IC are commonly seen in the elderly. They might have little discriminatory power in the elderly, although we conducted our study with an age-matched control group to identify the best predisposing factors. Nevertheless, our study showed the possibility of constipation conditions and initial laboratory findings being of great importance in portending IC after glycerin enema administration.

CT plays an important role in the assessment and triage of patients with IC in the acute phase[34]: Defining the injured colonic segment, suggesting irreversibility of bowel necrosis, detecting the complication, and excluding non-ischemic causes. However, our study identified diagnostic difficulties and errors on CT in diagnosing glycerin enema-related IC, which was 36.8% of the IC group. In the current study, contrast-enhanced CT did not show a decreased enhancement of the colonic wall in 44.4% of the IC group. This may reflect an early episode of IC, making it difficult to distinguish IC from non-ischemic colitis. However, the imaging findings and regional distribution of glycerin enema-related IC in our study were not significantly different from those in the published literature on non-occlusive IC[32,35]. Therefore, this may be due to a lack of knowledge and awareness regarding the acute clinical setting (i.e., IC) occurring in the elderly following glycerin-enema administration. Therefore, in this setting, the interpretation of CT findings may require more attention, although the misdiagnosis may not be of clinical relevance due to the full consideration of all the available evidence in diagnosing IC.

Our study has some limitations. First, the retrospective nature of the study may cause a selection bias in the data analysis. Second, the small number of study patients may lead to a lack of statistical power in our results. However, the rarity of the disease entity investigated here can offset these weaknesses of our study. Third, our study was conducted based on a single center experience. Therefore, the general application of our results may not be appropriate. Fourth, the clinical information regarding ICrelated medications and medical history may not be sufficient, although the clinical information is not as comprehensive for patients hospitalized in the ED. Fifth, the incidence of enema-related IC can be underestimated because the current study may have consisted of patients with high suspicion of IC. A previous study showed that this condition was initially suspected in only 25% of patients[36]. The diagnosis of IC depends on the severity of the presentation. Patients with transient IC may be asymptomatic after enema administration. Moreover, the initial presentation of IC is nonspecific. As a result, there could be a number of cases that were lost to follow-up in our study. Finally, as previously mentioned, we did not clarify whether the crystal deposition of Kalimate in the colon induces IC or not. To resolve this issue, it is essential to investigate the presence or absence and the amount of crystal deposition in the non-IC group receiving Kalimate enema, although they do not receive endoscopic biopsy in the colon unless acute abdominal symptoms exist. Therefore, this is an inevitable limitation in a retrospective observational study.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, glycerin enema-related IC occurred in 0.23% of the patients, occurring mostly in the elderly in the early period following enema administration. Despite the rarity of this disease entity, it can lead to a relatively severe IC, resulting in the need for surgical resection. Glycerin enema-related IC was associated with the constipation score, and leukocytosis. These data could provide useful clues for the triage of patients necessitating observation after glycerin enema in the ED.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research methods

We analyzed data from the database of patients with IC after enema administration at the Emergency Department of the Asan Medical Center from 2010 to 2018. The symptoms, laboratory findings, age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index score, constipation score, medication, time interval from enema administration to occurrence of IC, treatment, and treatment outcome were analyzed.

Research results

The incidence of IC was 0.23%, and it occurred mostly in elderly patients in the early period following glycerin enema administration but not after the use of other enema agents. The constipation score and leukocytosis were independent risk factors for glycerin-related IC.

Research conclusions

We found out that glycerin-related IC is very rare, but mainly occurs in the elderly in the early post-enema period. The constipation score and leukocytosis could help in prediction of an IC following glycerin enema.

Research perspectives

This could provide useful information for the triage of patients necessitating observation after glycerin enema administration in the emergency department.

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Associations of content and gene polymorphism of macrophage inhibitory factor-1 and chronic hepatitis C virus infection

- Focus on gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with cystic fibrosis

- Efficacy and safety of non-pharmacological interventions for irritable bowel syndrome in adults

- Endoscopic gastric fenestration of debriding pancreatic walled-off necrosis: A pilot study

- Older age, longer procedures and tandem endoscopic-ultrasound as risk factors for post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography bacteremia

- Escalating complexity of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography over the last decade with increasing reliance on advanced cannulation techniques