Focus on gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with cystic fibrosis

2020-12-11AnnaritaBongiovanniSaraMantiGiuseppeFabioParisiMariaPapaleEnzaMuleNovellaRotoloSalvatoreLeonardi

Annarita Bongiovanni, Sara Manti, Giuseppe Fabio Parisi, Maria Papale, Enza Mule, Novella Rotolo, Salvatore Leonardi

Abstract Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common gastrointestinal disorder in cystic fibrosis (CF), and based on various studies, its prevalence is elevated since childhood. There are several pathogenetic mechanisms on the basis of association between CF and GERD. However, there are no specific guidelines for GERD in CF patients, so diagnosis is based on guidelines performed on patients not affected by CF. The aim of this review is to provide the pathophysiology, diagnostic and therapeutic options, complications, and future directions in the management of GERD patients with CF.

Key Words: Adult; Children; Cystic Fibrosis; Gastroesophageal reflux

INTRODUCTION

According to the Montreal definition[1], gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the disorder occurring when the rise of gastric contents leads to the onset of signs and symptoms, varying in accordance to the age. The symptoms more frequently occurring in children are the sense of acidity in the mouth, difficulty in swallowing, burning behind the sternum, habitual vomiting, and abdominal pain, but sometimes, even irritability, chronic cough, laryngeal stridor, recurrent asthma, recurrent pneumonia, apparent life-threatening event, Sandifer syndrome can be also present. In adults, GERD may present both with “typical” symptoms, such as heartburn and regurgitation, and “atypical” manifestations including ear, nose, and throat diseases; pulmonary (chronic cough or asthma); or cardiac (noncardiac chest pain) affections, laryngitis, sinusitis, otitis, hoarseness, pneumonia, bronchitis, interstitial fibrosis, sinus arrhythmia, dental erosions, and halitosis[2].

GERD is a very frequent pathology in patients with severe neuro-motor delay or predisposing disease (diaphragmatic hernia, oesophageal atresia) in which it often tends to complicate with the onset of esophagitis, pneumonia due to aspiration of the refluxed food, narrowing of the oesophagus (peptic stenosis), hematemesis, anaemia, and dysphagia.

GERD is one of the most common gastrointestinal manifestations of CF, probably playing a role in the pathogenesis of the respiratory disease[3]. Firstly described in 1975 by Feigelson and Sauvegrain[4], the prevalence of acid gastroesophageal reflux (GER) in CF ranges between 35% and 81%.

The aim of this review is to provide the pathophysiology, diagnostic and therapeutic options, complications, and future directions in the management of GERD patients with CF.

METHODS

Research strategy

This review has been conducted employing PubMed and Science Direct databases. On these websites, we searched for articles from January 1, 2010, to December 2019, using key terms related to GERD: “gastroesophageal reflux disease”, “GERD”, “cystic fibrosis”, “CF”, “medical therapy”, “surgical therapy”, “therapy”, “treatment”, “children”, and “adult”.

Study selection

English language, publication in peer reviewed journals, and year of publication at least 2010 were adopted as inclusion criteria. Article excluded were editorial, commentary, case report, and case series.

Articles were excluded by title, abstract, or full text for irrelevance to the investigated issue. Lastly, the references of the selected articles were also reviewed.

MECHANISMS OF GER IN PATIENTS WITH CF

Several theories have been described to understand the mechanisms of the association between GER and CF.

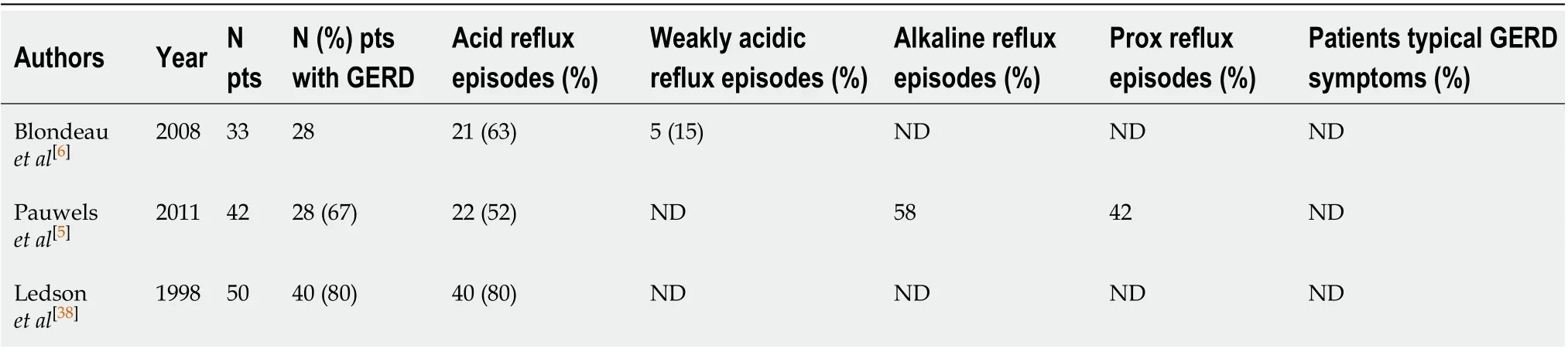

An increased frequency of transient lower oesophageal sphincter (LES) relaxations (TLESRs) and a delayed gastric emptying play an important role. Moreover, chronic cough, higher gastroesophageal pressure gradient, altered intestinal motility, chest physiotherapy, and a low gastric pH seem to increase the risk for GERD in CF. Pauwelset al[5]showed that most reflux in these patients reached the proximal oesophagus, and most refluxes were acid. Specifically, authors showed a delayed gastric emptying in 33% of CF patients and an acid GER in 67% of patients with CF[5]. The age, gender, body mass index (BMI) or diabetic status seemed did not affect GER incidence in CF patients[5].

Blondeauet al[6]reported that a higher cough frequency and poorer lung function were associated with a major risk of aspiration and reflux. By inducing microaspirations and bronchospasms as well as exacerbating bronchial inflammation, GERD exacerbates the chronic bronchopulmonary diseases and contributes to the deterioration in respiratory function especially in advanced forms[7]. Moreover, the lipid material presents in gastric content, if aspirated, can be phagocytized by macrophages resident in the airways which, in turn, induce an inflammatory reaction with the recruitment of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and release of neutrophilderived products such as interleukin (IL)-8[7]. In line with these findings, an increased tracheobronchial mucus secretion secondary to oesophageal acidification and an IL-8-mediated airway neutrophilic inflammation have been detected in children with GER and “difficult to treat” recurrent asthma-like symptoms[8].

CHARACTERISTICS OF GERD IN ADULT PATIENTS WITH CF

Woodleyet al[9]showed that reflux symptoms were more frequent in CF patients as compared to non CF patients. The prevalence of extraesophageal reflux in the adult CF population ranges from 55% to 90%[6]. GERD in non-CF patients, presents a prevalence of 18.1%-27.8%[10]. Diagnosis of GERD, in general population, is typically based on typical symptoms and response an empiric trial with acid suppressors. The most common cause of GERD in non CF-patients is transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs). TLESRs are brief moments of lower esophageal sphincter tone inhibition that are independent of a swallow. While these are physiologic in nature, there is an increase in frequency in the postprandial phase and they contribute greatly to acid reflux in patients with GERD. Other factors include reduced LES pressure, hiatal hernias, impaired esophageal clearance, and delayed gastric emptying. In non CF-patients, older age, smoking, excessive body mass index (BMI), anxiety/ depression, and less physical activity are the most common risk factors for GERD[11-14]. Physical activity appears to be protective, except when performed post-prandially[15,16]. By using a combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH measurement (MII-pH), Blondeauet al[6]reported that GER was a primary phenomenon in CF patients and not secondary to cough and, also, that the majority of reflux events were acidic in nature, while weakly acidic reflux was less common and weakly alkaline reflux was rare. Particularly, age seemed to be associated with increased acid exposure and both, in turn, are correlated to a reduced baseline impedance in the distal oesophagus[17].

Relationship between GERD and respiratory diseases is controversial. GERD seems to exacerbate respiratory disease like asthma and COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease)[18-21]. The high prevalence of GERD in asthmatics may at least partly be the consequence of asthma itself or of asthma therapy. The cough and the increased respiratory effort in asthmatic patients seem to exacerbate GER by causing an increased pressure gradient across the lower oesophageal sphincter[21]. GER is a common trigger of asthma and a correct treatment directed toward reflux may improve asthma symptomatology and pulmonary function[22,23]. GER and acid aspiration are also involved in post-transplant allograft dysfunction through several mechanisms. Acid reflux may worse bronchospasm and airway oedema. Microaspiration has been shown to directly impair pulmonary function. After lung transplantation, defense pulmonary mechanisms as cough, and mucociliary clearance are totally absent or reduced, so this is related to an exacerbation of pulmonary dysfunction[24]. The prevalence of GER symptoms both in adults and children with CF ranges between 25%-81%[24-27]. More of 50% CF patients had reflux symptoms, but in a third of CF patients, GERD can be clinically silent[28]. Females with CF seemed to have more frequent and severe GER symptoms, but the cause is unclear. Oral contraception is reported to have a rule on maintaining GER symptoms[29]. Also, CF patients with weight loss had more GER symptoms than patients with good weight, indeed GER has been shown to complicate malnutrition in CF. Although the most common symptoms of GERD in non CF-patients are heartburn and regurgitation, water brash, chest or epigastric pain, dysphagia, belching, nausea, and bloating can also occur. Cough, hoarseness, throat clearing, throat pain or burning, wheezing, and sleep disturbances may be present as extraesophageal symptoms[30].

CHARACTERISTICS OF GERD IN PEDIATRIC PATIENTS WITH CF

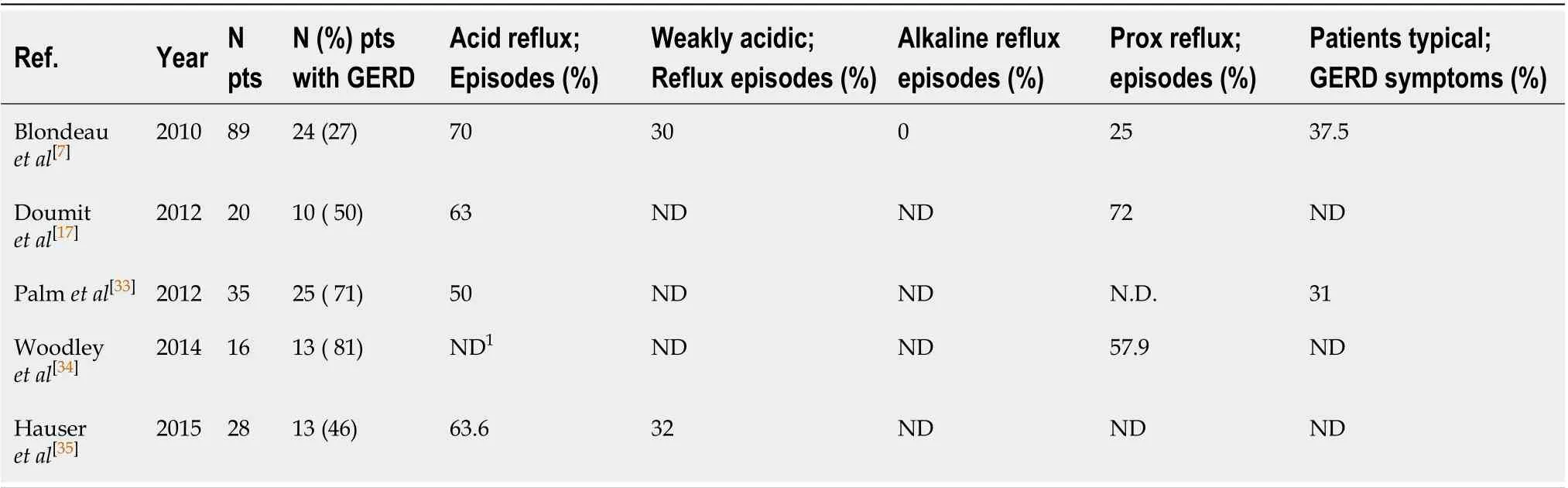

Fewer authors examined GERD in children with CF (Table 1)[7,26,31-36]. Based on these studies, the prevalence of GERD is elevated in patients with CF since childhood. The prevalence of GERD is about 27%-87%, and acid reflux is more prevalent than weakly acidic reflux or alkaline reflux. Furthermore, 25%-72% of episodes of refluxes are proximal events. Typical symptoms of reflux are present only in 30% of patients. Woodleyet al[9]showed that age did not modify significantly the association between GER and percent predicted forced expiratory volume in one minute (ppFEV1). A negative correlation between age and basal impedance in the distal oesophagus is present in CF patient. 50% of CF children had an abnormal baseline values in the distal oesophagus, but adult CF patients have 11.0-times more an abnormally low basal impedance in the distal oesophagus than children. In conclusion, older patients with CF are more likely experiencing mucosal injury due to increased acid exposure.

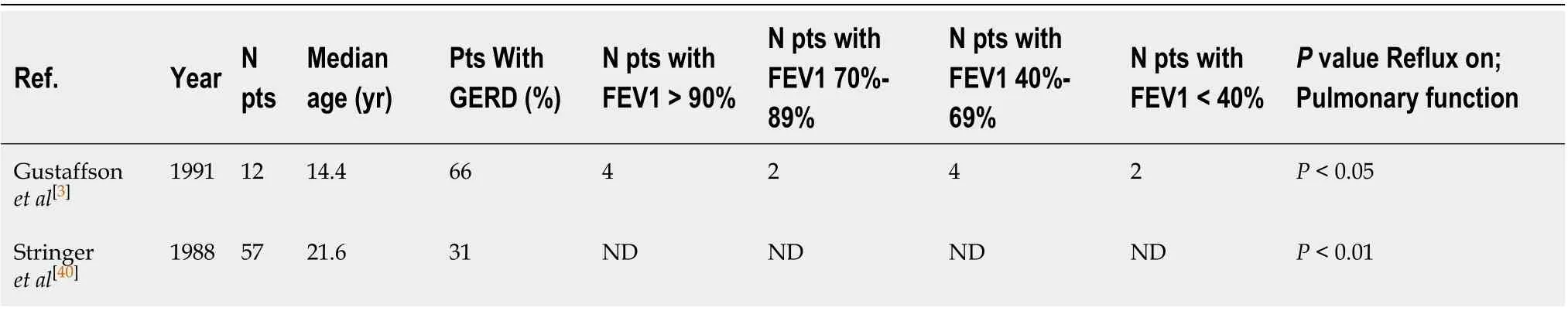

IMPACT OF GERD IN PULMONARY FUNCTION

Impact of GERD on the pulmonary function in CF patients has not been clearly established. Sabatiet al[37]showed that GER symptoms and severity of symptoms were not predictive of FEV1 or FVC, but a lot of studies[31,38-41]show an association between GER and more severe lung disease with increased numbers of respiratory exacerbations in CF patients. In a study enrolling paediatric patients with CF, GER was correlating with decreased pulmonary function and early infection ofPseudomonas aeruginosaandStaphylococcus aureus[42]. Also, Palmet al[33]showed a high incidence ofPseudomonas aeruginosainfection in CF children with GERD. The mechanisms are still unknown. Reflux into the proximal oesophagus may result in intermittent microaspiration, starting a vicious cycle of inflammation, infection, and onset and/or worsening of lung disease. The role of the esophageal diseases in airway disorders has not been yet completely understood. The airway hyperresponsiveness caused by the direct mucosa damage increased vagal tone and bronchial spasm[43]. Also, neuroinflammatory reflexes may have a role in the airway responsiveness by releasing tachykinins peptides, including P, and A neuro-quinine. The combination of these mechanisms can cause the afferent vagus impulses and, finally, airway stimulation. Despite the numerous studies about the GERD and pulmonary function impairment in patients with known pulmonary diseases, a study showed that patients with GERD seem to have smaller airway disease even in the absence of pulmonary symptoms[44].

GERD is a common comorbidity in several pulmonary diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)[45]. GERD was associated with faster COPD disease progression as measured by rapid FEV1 decline and quantitative computed tomography measured air trapping, but not by slopes of lung function[46]. By causing aspiration-mediated lung injury, it has been hypothesized that GERD can play a significant role in the decline in lung function both before and after lung transplantation, as assessed by the very high prevalence of GERD in patients undergoing to lung transplantion. Accordingly, it has been suggested that every patient early after lung transplant is screened for GERD by manometry, pH monitoring, and, if possible, by bronchoscopy with BALF for detection of pepsin or bile acids, irrespective of the presence of symptoms. If GERD is diagnosed, a fundoplication should be performed as soon as possible and before the development of BOS. It has been hypothesized that whether on the hand the microaspiration of gastric acid into the airways can lead to the onset or exacerbation of chronic airway inflammation and its progression to pulmonary fibrosis, on the other hand the vagal mediated esophageal-bronchial reflex participate in the onset or worsening bronchoconstriction[46-48].

Additionally, the microaspiration of gastric contents into the airways causes surfactant, injury, which, in turn, leads to the collapse of alveoli and development of microatelectasis. This is manifested by an impaired diffusion of gases associated with expansion of dead space, which is reflecting as an increasing intrapulmonary shunt[46-50].

DIAGNOSIS OF GERD

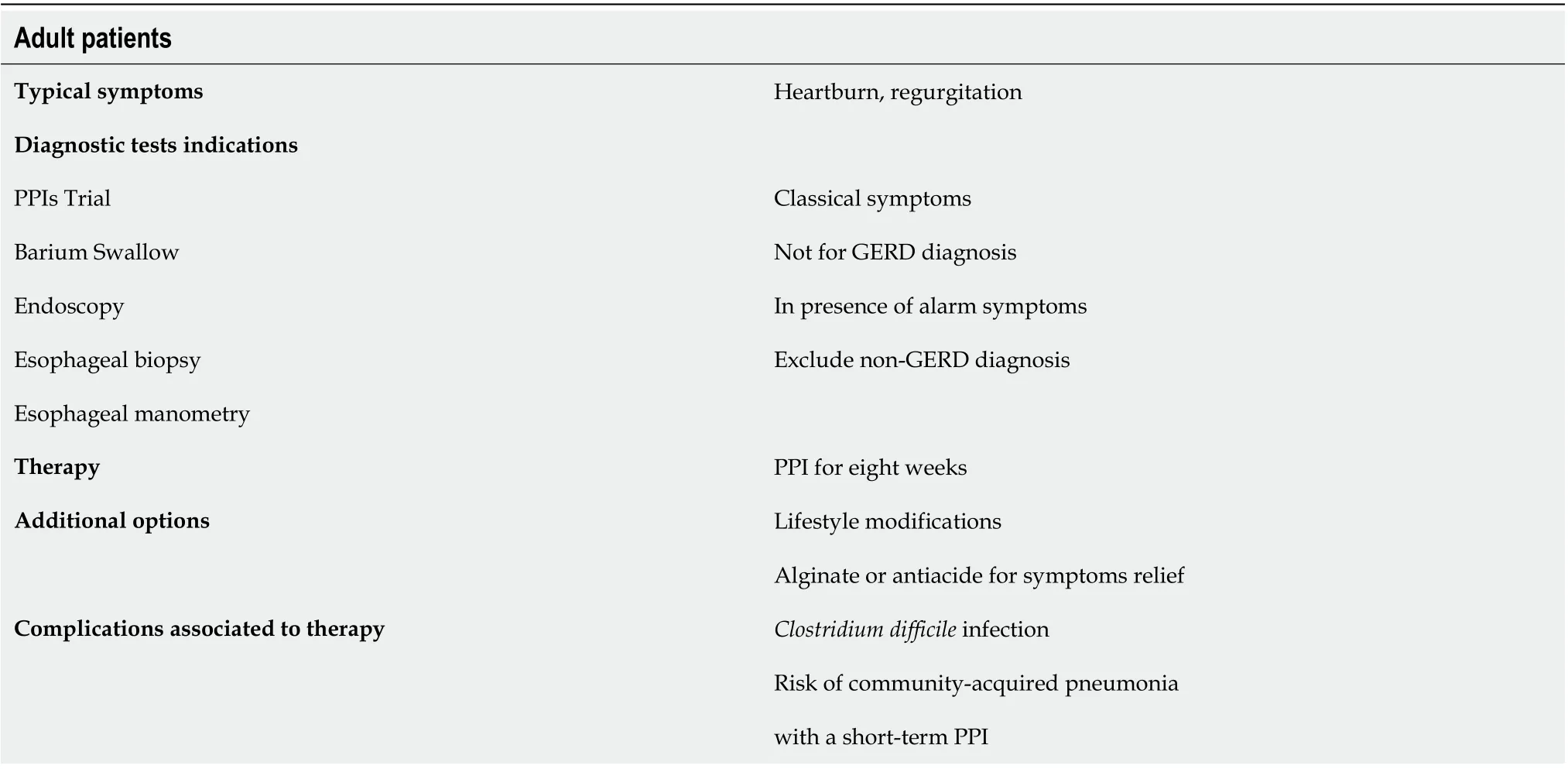

Due to the lack of specific guidelines for GERD in CF, actually, the diagnosis of GERD in adult-patients with CF is based on American and European guidelines performedon patients not affected by CF[34-38]. It is necessary to distinguish the diagnostic approach in adults and children (Table 2 and 3).

Table 1 Gastroesophageal reflux disease in adults with cystic fibrosis

Diagnosis of GERD in adults

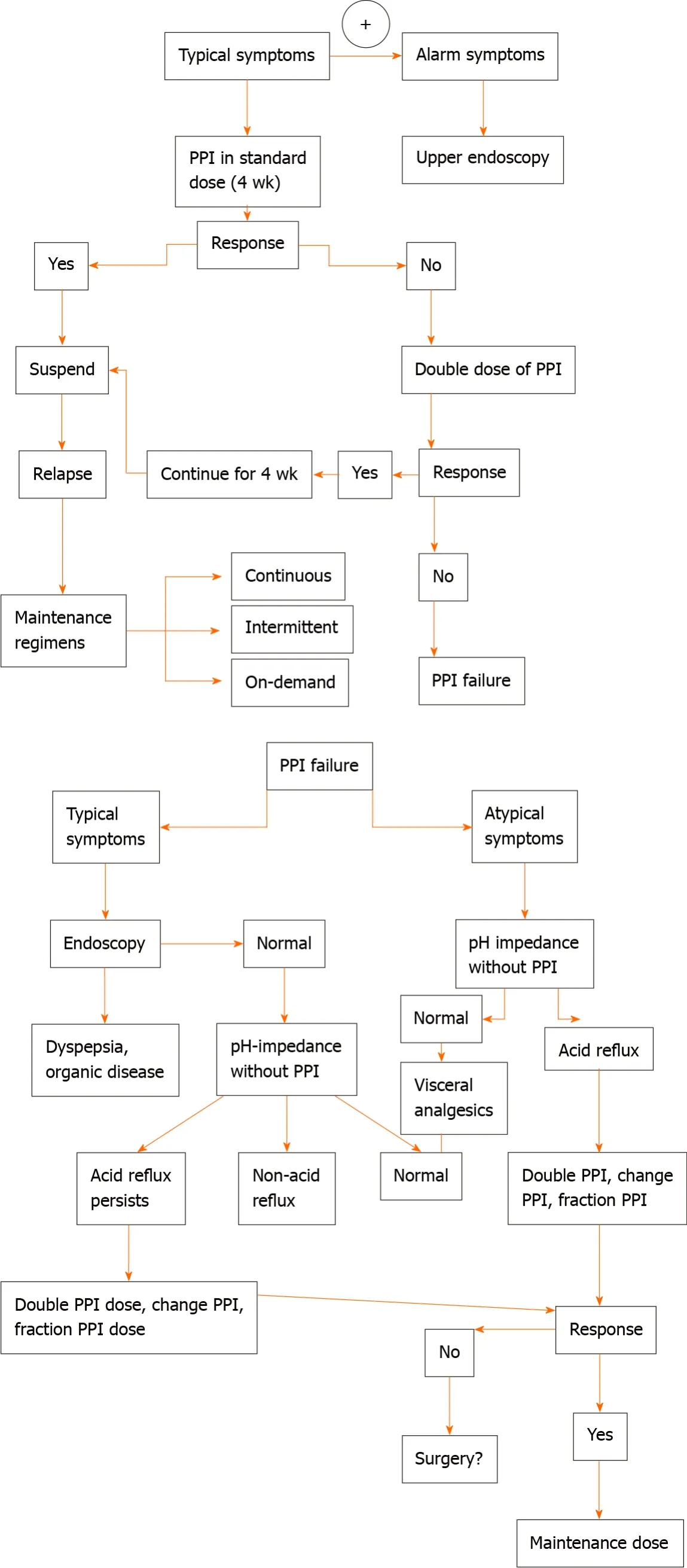

The suspect of GERD in adults is based on the setting of typical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation, and, according to the guidelines[42,51-58], empirical medical therapy with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is recommended for 8 wk (Table 4). Barium radiograph and esophagal manometry should be not performed to make a diagnosis of GERD. The use of upper gastrointestinal is limited to investigate anatomical factors favouring GER. Combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH-measurement distinguishes the acid from non-acid reflux and also provides information about the quality of the refluxate (liquid, gas or mixed)[42,51-58].

In patients with reflux symptoms despite standard dose once daily PPI, options include splitting the dose, doubling the PPI dose, switching to another PPI, and adding a prokinetic drug. However, if symptoms persist after this treatment, an oesophageal multi-channel impedance pH-measurement should be performed. When esophagitis, gastritis, and persistence of symptoms despite medical management occur, the esophagastroduodenal endoscopy is recommended to exclude the most common differential diagnosis such as eosinophilic esophagitis, gastritis, duodenitis, oesophageal candidiasis, anatomical abnormalities. The 24-h esophageal pH monitoring is the gold standard to quantify GER. Surgical options are recommended for patients who do not respond to PPI therapy[42,51-58].

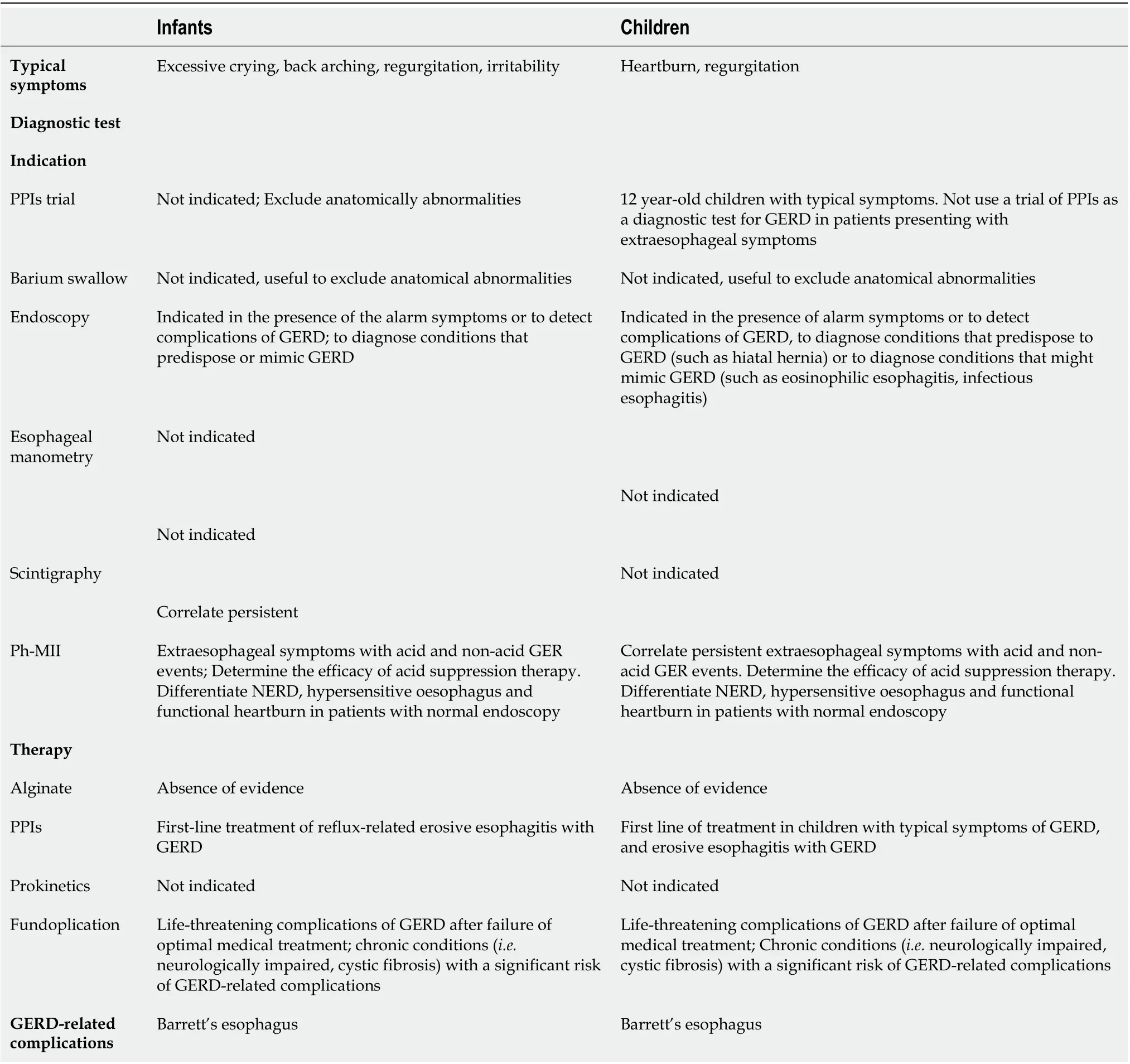

Diagnosis of GERD in children

According to the guidelines[39-41], it was created different diagnostic approaches for GERD even in infants and children. Most refluxes in infants are benign, thus, only in presence of red flags (e.g., weight loss, lethargy, fever, irritability, dysuria, seizures, the onset of regurgitation/vomiting lasts longer than six months or increasing/persisting > 12-18 mo of age, bulging fontanel/rapidly increasing head circumference, nocturnal vomiting, hematemesis, chronic diarrhoea, rectal bleeding), diagnostic investigations are required (Table 5)[55-57].

Children with typical symptoms, such as regurgitation and heartburn, but in absence of alarm signs, should modify lifestyle and dietary management. If the symptoms do not improve after these changes, acid suppression with PPI for 4-8 wk is suggested. However, if clinical symptoms continue or there is the inability to stop treatment with PPIs, a diagnostic tool with endoscopy is necessary. If the endoscopy does reveal no erosions and clinical symptoms are responsive to treatment with PPI, children should continue PPIs with periodic weaning attempts. If the endoscopy does reveal no erosions and but symptoms are persistent despite PPIs, multichannel intraluminal impedance-pH is attempted. No evidence is supporting empirical therapy with PPIs for the diagnosis of GERD in children. However, evidence supports that the presence of typical symptoms in an older child or adolescent can suggest GERD, thus, a diagnostic trial of PPIs can be justified for four to eight weeks[55-57].

There is insufficient evidence to support the routine use of pH-impedance in diagnosing GERD in the pediatric population. But it could be useful to correlate persistent symptoms with acid GER events, especially in cases of GERD refractory to dietary, to acid-suppressive therapy. The use of upper gastrointestinal is limited to investigate anatomical factors favouring GER. Esophagastroduodenal endoscopy is recommended in case of clinical suspicion of gastritis and/or esophagitis. Combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH-measurement distinguishes the acidfrom non-acid reflux and also provides information about the quality of the refluxate (liquid, gas or mixed).

Table 2 Diagnostic and therapeutic management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in adult patients with cystic fibrosis

Eosinophilic esophagitis, gastritis, duodenitis, esophageal candidiasis, anatomical abnormalities are the most common differential diagnosis for GERD symptoms[55-57].

GERD TREATMENT IN PATIENTS WITH CF

In patients experiencing a typical history of uncomplicated GERD, an initial trial of empiric medication, such as PPI treatment up to 8 wk, are suggested (Figure 1). In patients with weakly acidic or alkaline GERD, not completely respond to acidsuppressive therapy[55-57], a 24-h oesophageal pH/impedance monitoring may be considered.

Lifestyle modifications represent the first therapeutic approach for GERD in non CF-patients, and medical therapy is prescribed in patients who continue to have bothersome GERD-related symptoms.

In patients with severe CF and uncontrolled GERD, medical therapies are often insufficient; so, it should be useful an early Nissen fundoplication to prevent lung functions and improve pulmonary and nutritional status. Sheikhet al[8]reported, in 48 CF patients and uncontrolled GERD, a lower incidence of pulmonary exacerbations, an increase in weight gain and a slower decline in % predicted FEV1 at 2 years after Nissen fundoplication, compared to 2 years before surgery. Boeshet al[55]observed a high likelihood of persistent clinical GERD and medication use in patients underwent to fundoplication, with a low improvement in nutritional and pulmonary function outcomes.

The role of PPIs in modifying respiratory outcomes is unclear. Various studies explored the effects of PPIs in CF patients. Dimangoet al[56]showed a trend towards earlier and more frequent exacerbations in patients receiving PPIs therapy; Pauwelset al[58]demonstrated that PPIs therapy in CF patients resulted paradoxically in increased inflammatory effects on the airway. A meta-analysis including 26 studies performed in general population[59]showed an increased risk of community-acquired pneumonia of 1.5 fold for patients receiving PPIs treatment.

Although GER causes a lot of gastric complications such as gastric or other gastrointestinal malignancies and changes in the gut microbiota[60-65], none of these was statistically confirmed. In clinical practice, it is needed to carefully assess the therapeutic management of the patient requiring long-term PPIs treatment.

Table 3 Diagnostic and therapeutic management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Acute life-threatening events caused by GERD, chronic aspiration, failure to thrive, or persistent GERD after a trial of medical therapy are the indications for surgical treatment of GERD in children. The laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication is the most common procedure performed. A fundoplication reduces reflux by increasing LES pressure, reducing the frequency of spontaneous relaxations of the LES and strengthening angle of His, allowing for a second antireflux barrier between the stomach and the oesophagus. Intolerance to medical therapy or inadequate symptom control despite optimal medical management, complications of GERD, including Barrett’s oesophagus or stricturing, presence of GERD with difficult to manage extraoesophageal manifestations are the indications for surgical management in adults[66]. Complications after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication can occur and include hiatal hernia, slipped wrap, recurrent GERD, persistent dysphagia, and gas bloat syndrome[67]. In CF-patients persistent nutritional decline, frequent pulmonary exacerbations, and decline in pulmonary function are common indications for fundoplication in CF-patients[3,68,69]. Boeschet al[55]described a little apparent benefit for nutritional and pulmonary outcomes after fundoplication in these patients. Changes in weight parameters seem to be relevant outcomes to assess the nutrition benefits ofantireflux surgery in CF patients. Some studies showed a significant increase in weight post surgery[70,71], while other studies revealed no significant change from before to after surgery[72,73]. Boeschet al[55]showed that even after surgery, many patients did not report significant clinical improvement, including pulmonary disease, and/or nutrition. Sheikhet al[8]noted better pulmonary and nutritional outcomes among patients with milder lung disease compared to those with severe lung disease, and among patients who received gastrostomy feeding tube.

Table 4 Gastroesophageal reflux disease in children with cystic fibrosis

Table 5 Impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on pulmonary disease

EMERGING THERAPIES ON GERD IN PATIENTS WITH CF

Although alternative drugs such as antioxidant agents[74-78], postural drainage[79], respiratory physiotherapy[80], and inhaled beta(2)-adrenergic agonists[81]have been proposed in treating GERD in CF, only a new group of drugs called CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) modulators seem able to correct the basic effect of CFTR and, consequently, also GERD in this population. Ivacaftor (Kalydeco) and the combination of Ivacaftor and Lumacaftor (Orkambi) are two new molecules that improve chloride transport through CFTR channels respectively in patients with gating mutations and for patients homozygous for the F508del mutation[82]. Ivacaftor treatment contributes to the reduction of reflux symptoms and has a beneficial effect on FEV1[83,84]. Zeybelet al[84]revealed that a population of CF patients treated with Ivacaftor for 12 mo showed a decline in symptoms of extraesophageal reflux, a significant weight gain as well as an improvement in FEV1.

PROGNOSIS

Figure 1 Flow-chart on management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in cystic fibrosis patients. PPI: Proton pump inhibitor.

A significant correlation between the oesophageal acid exposure and the number of coughs was found, and it could be responsible to microaspiration and the enhancement of the cough reflex[6]. GERD in CF has been associated both with decline in lung function and low BMI[85,86]. For CF patients age 20 years or older, it is recommended that women maintain a BMI at or above 22 and that men maintain a BMI at or above 23[87]. Having a BMI major than or equal to 50% correlates with the predicted percentage of FEV1 greater than or equal to 90%[88]. CF patients may experience a major likelihood of long-term sequelae of chronic GERD, including Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Among patients with CF, Barrett’s esophagus is more common than in general population (5%, 7%vs2%, 1%)[88]. The reasons for this increased risk have not been explained, GERD represents the modifiable risk factor.

CONCLUSION

The gastrointestinal tract is also involved in CF, and in particular, GERD is a common manifestation. The characteristic of GERD in CF patients is featured by a high prevalence of extraesophageal symptoms, prevalence of acidic reflux, and a close relationship between GERD and respiratory function. A correct diagnosis is necessary to reduce complications of GERD both in children and adults affected by CF. Diagnosis is based on the clinical approach and/or specific diagnostic investigations in accordance to the age of the patients. The treatment is based on PPIs but a clear timing of treatment is not still defined. Further prospective investigations to assess the role of GER in CF and the risks and benefits of pharmacologic and/or surgical therapies are warranted.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Associations of content and gene polymorphism of macrophage inhibitory factor-1 and chronic hepatitis C virus infection

- Efficacy and safety of non-pharmacological interventions for irritable bowel syndrome in adults

- Endoscopic gastric fenestration of debriding pancreatic walled-off necrosis: A pilot study

- Older age, longer procedures and tandem endoscopic-ultrasound as risk factors for post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography bacteremia

- Escalating complexity of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography over the last decade with increasing reliance on advanced cannulation techniques

- Efficacy and safety of anti-hepatic fibrosis drugs