阳台:现代建筑元素的传奇

2020-10-22汤姆阿韦马特TomAvermaete

汤姆·阿韦马特/Tom Avermaete

徐知兰 译/Translated by XU Zhilan

“没有任何其他元素像过于宽阔的阳台一样破坏了建筑立面的开洞形式……优秀的建筑不会出现这些元素。”[1]148-149

令人烦恼的建筑元素登上历史舞台

阳台原先是军事堡垒外墙上的附属物,是用来向敌人投掷导弹的空间,一直以来都是涵义丰富的建筑元素。自从法国建筑理论家卡特勒梅尔·德·坎西于1833年在其《建筑历史辞典》中首次提到阳台之后,它就一直被当成一个怪物,一位不速之客,甚至惹是生非的角色。和许多19世纪的建筑师一样,卡特勒梅尔对现代主义的“阳台潮流”持有极端批判的态度,并认为“建筑作出的牺牲最大,尤其是外立面及其细部比例。”[1]他认为阳台玷污了建筑,并把它形容为“开胃菜假发”,理由是“因为它与主体结构无关的性质”[1]142-146。

如何驯服阳台这一令人烦恼的建筑元素,把它纳入现代建筑元素的常用清单中,成为现代主义建筑运动的一项重大挑战。在建筑中吸收阳台的元素,最初是通过改革派的措辞来实现的,即提供民主的健康与卫生条件,而在20世纪初,这与得到充足的日照和呼吸新鲜空气息息相关[2]。在19世纪晚期的建筑学讨论中仍然令人感到不安的元素,现在却已占据了建筑学话语的核心地位。

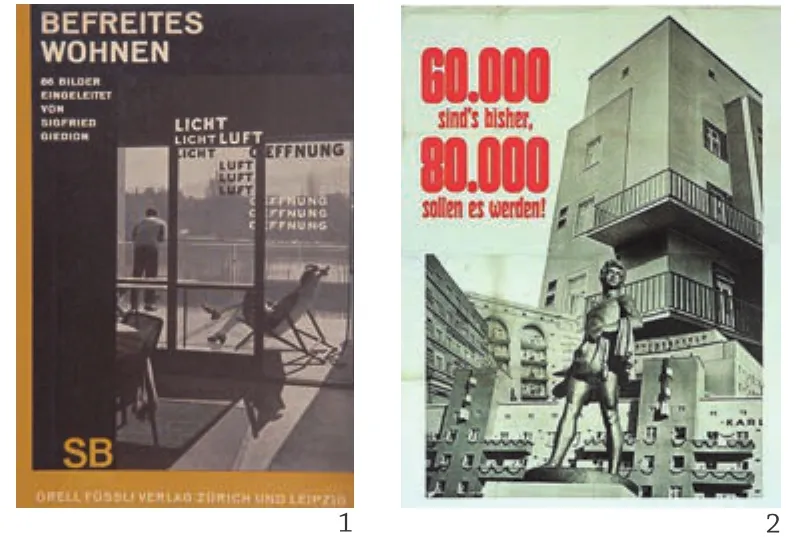

1929年出版的《自由生活》是第一届国际现代建筑协会(CIAM)的大会成果,瑞士批评家希格弗莱德·吉迪恩通过封面图片,把阳台牢牢置于更广泛的现代主义修辞语境下,是走向新生活方式的解放宣言……[3]阳台被描绘为引入日照、空气和开阔空间的建筑元素。在这本书的插图中,通过和黑暗的监狱老牢房进行对比,阳台被进一步纳入了有逻辑的现代主义居所。文字和图片都暗示着现代建筑要素具有治疗的作用,能够治愈被束缚在旧式经济住房中的住户。吉迪恩曾经在另一本著作里解释过:“这种‘新建筑’已经一次又一次无意识地使用这些突出于立面的‘阳台’了。为什么呢?因为人们需要居住在能够尽可能突破旧式均衡感的建筑里,而那种感觉恰恰来源于军事堡垒一般的幽闭空间。”[4]到了20世纪20年代和30年代,阳台逐渐成为一些现代建筑理论和实践的核心要素[5],它开始成为现代主义住宅具有的显著特征。

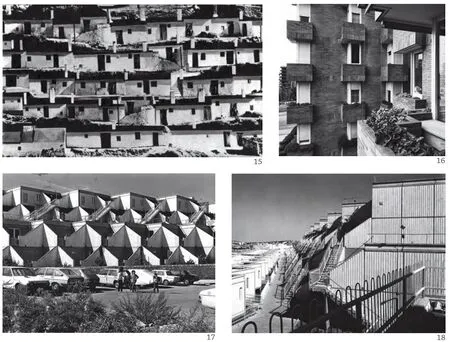

现代阳台具有自由解放和疗愈性的特点不仅事关建筑学的先锋派,在各类政治理论中也得到了响应。阳台在红色维也纳的住宅政治中扮演了核心角色,正如卡尔·恩于1931年在声名狼藉的卡尔马克思大院i投入使用的当天发表的报刊文章所述:“这些住宅没有任何冗余的装饰,光洁平整,但它们拥有价值连城的珍宝,那就是沿着整个正立面连续展开的阳台,让每一套公寓都能有一座阳台。”[6]就在它建成不久之后制作的一幅住宅大楼拼贴画,已经领会到了对于重获新生的人来说,阳台在维也纳的居住政治中多么至关重要。

1 希格弗莱德·吉迪恩所著的《自由的居所》封面上的阳台看起来像是日照、空气和开放性的先驱者,1929/Cover of Sigfried Giedion,Befreites Wohnen.On which the balcony appears as harbringer of light, air and openness, 1929.

2 用卡尔·马克思大院的各种阳台拼贴画来宣传维也纳住宅政治的海报,齐格弗里德·维埃尔,1932/Poster championing Viennese housing politics with collage of various balconies at the Karl-Marx-Hof, Siegfried Weyr, 1932.

个体与群体,为最多的人提供遮蔽

战后的建筑文化激活了阳台的要素,以应对由建成环境的政治、社会、文化和经济影响变化所带来的各种问题。阳台成为战后诸多核心问题中最首要和最重要的协调因素,对于这一点,社会学家丹尼尔·贝尔在1956年总结道:“对一些人来说,它可能可以让我们从机械化的社会中获得个体的自我感受。”[7]在二战之后从北半球到南半球、从斯德哥尔摩到卡萨布兰卡的无数大规模住宅开发项目中,如何在更广阔的城市环境中为普罗大众创造以及个人领域的问题将成为城市规划师和建筑师最关心的核心议题之一。

阳台成为各类不同住宅项目中应对这种群体与个体之间矛盾的“最出色的建筑元素”。法国建筑师杰拉德·格兰德沃在巴黎附近的克雷代伊设计的住宅项目“卷心菜”就为我们提供了一个有趣的案例,它是法国政府推动的一系列住宅项目“光荣的30个项目”[8]之一。“卷心菜”建筑群由10座15层高的塔楼组成,建成于1970年代早期,是出于“为最多的人提供住房”的目的进行的实验性项目。这一类项目所面临的挑战在于,这些为未来大众社会所设计的建成环境产生了新的集体主义和匿名性之间的关系。

3 阳台在“卷心菜”项目中是个人与群体之间的调节器,巴黎附近的克雷代伊,杰拉德·格兰德沃,1972/The balcony as a regulator between individual and mass at Les Choux,Creteil, near Paris, Gerard Grandval, 1972 (摄影/Photo:Henri Locuratolo)

在法国预制混凝土技术发展的支持下,格兰德沃提出了一套花瓣状阳台的体系,可以为建筑提供独特的造型和相应的可识别性,但最重要的是它设计了新的形式,可以用来在私人和集体的领域边界提供“遮蔽”,也让住户在个人空间体验的过程中感受到高度私密性与公共领域之间的关系:“在克雷代伊,反而有一种想要打破平庸的大型组装构件的欲望。然而,举例来说,其表面则是定额分配的。为了补偿这一缺陷,我想象出宽阔的阳台。我认为,它们必须能够避免被他人窥视的侵扰,否则人们就不会使用它们。这就是我获得悬挑的花瓣形式灵感的过程。”[9]

作为一种在法国政府主导的强烈集体主义导向的建成环境和个人之间进行调和的尝试,格兰德沃采用了预制混凝土的阳台元素。在最广大人民的社会现实和个人的现实之间的的领域能够通过阳台进行表达,说明阳台在其中具有关键作用。

纪念碑和壁龛:里卡多-波菲尔,西班牙巴塞罗那市瓦尔登

在西班牙弗朗哥统治时期,有许多关于个体与大众之间关系的思考。弗朗哥政府对公共住宅几乎不进行任何投入,其政策也主要倾向于补贴个人的按揭贷款,偶尔会建设少量的公共住宅项目。然而,西班牙建筑师波菲尔几乎和格兰德沃同时,也通过巴塞罗那的瓦尔登7号住宅项目,提出了他对大众与个体交汇的观点。波菲尔把这种交汇重新定义为大众住宅的纪念性尺度和居民人性化尺度之间的张力。阳台在这一定义中起到了重要的作用。在瓦尔登的住宅项目中,公寓建筑的纪念性通过一个被折叠进带有空腔的巨大城市形态中的封闭体量进行强调。

"Nothing spoils the form of the openings more then the inordinate length of the balcony…These elements are foreign to good architecture."[1]148-149

A Disturbing Element Entering the Stage

Originally a military entity that was attached to the wall of fortress and used to project missiles to the enemy,the balcony has always been a charged architectural element. From its very entry on the stage of modern architectural culture it has been looked upon as a stranger, an unwanted visitor or even a troublemaker –as emerges from the writings of the French architectural theoretician Quatremère de Quincy in hisDictionnaire Historique d’Architecture, from 1833.

As many 19th century architects, Quatremère was extremely criticical of the modern "balcony fashion"and held that "the architecture is most often sacrificed,especially the exterior facades and the proportions of their details."[1]He identified the balcony as a polluting element and described it as a "hors-d’oeuvre postiche" (appetizing hairpiece) "because of its nature,independent of the main construction."[1]142-146

Taming the disturbing architectural element of the balcony, making it part of a universalist catalogue of modern elements, would become one of the big challenges of the modern movement in architecture.This domestication of the balcony was primarily achieved by locating it within a reformist rhetoric of the provision of democratic admission to health and hygiene, which in the early twentieth century became strongly related to the access of sun and air.[2]What in the late 19th century was still discuss as a disconcerting element, was now given a place at the centre of modern architectural discourse.

On the cover ofBefreites Wohnen (freed living)that was published in 1929 as a result of the first Congres Internationale d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM)the Swiss critic Sigfried Giedion locates the balcony firmly in a broader modernist rhetoric on emancipation towards new ways of living...[3]The balcony is depicted as the element that introduces licht (light), luft (air)and oeffnung (openness). In the photographic pages of the book the balcony is further inserted into a modernist logic of dwelling by contrasting it with a dark prison cell. Text and images suggest that the modern architectural element has curing powers that have the capacity to heal the imprisoned occupant of oldfashioned tenements. In another publication Giedion explains that, "The 'new architecture' has unconsciously used these projecting 'balconies' again and again. Why?Because there exists the need to live in buildings that strive to overcome the old sense of equilibrium that was based only on fortress-like incarceration."[4]In the late 1920s and 1930s the balcony is gradually given a central place in several modern architectural discourses and practices.[5]It becomes a conspicuous feature of the modernist house.

The emancipatory and healing character of the modern balcony was not only a matter the architectural avant-garde, but also resonated in political discourses. In the housing politics of Red Vienna the balcony would receive a central role,as a newspaper article with Karl Ehn in 1931 on the opening day of the infamous Karl-Marx-Hof makes clear: "Smooth, without any unnecessary ornamentation, the houses were built, but so much more valuable jewelry are the balconies, which continuously expands the whole front, so that each apartment has a balcony."[6]A collage of the housing complex, made right after its completion, grasps how the balconies were crucial elements in the Viennese dwelling politics for a new man.

Individual and Mass, or Screening the Greatest Number

Within post-war architectural culture the element of the balcony is activated to deal with a variety of issues that emerge from the changing political, social, cultural and economic role of the built environment. The balcony becomes first and foremost a mediator in one of the central issues of the postwar period, which sociologist Daniel Bell summarized in 1956 as "the possibility for some few persons of achieving a sense of individual self in our mechanized society."[7]In the numerous large-scale housing developments that occur after the Second World War as well in the North as in the Global South, from Stockholm to Casablanca, this issue of creating and individual realm within a broader urban environment for the masses would become one of the central concerns of urban planers and architects.

The balcony becomes the "architectural element par-excellence" to deal with this issue of mass and individual in a wide variety of housing projects. The French architect Gerard Grandval offers an interesting example in his housing project Les Choux in Creteil near Paris, one of the multiple housing projects that was initiated by the national government in France ofles trente glorieuses.[8]The Les Choux complex which consists of ten towers, each fifteen stories high, was built in the early 1970s as an experimental approach with "housing for the greatest number". The challenge in these type of projects was the engagement with the new collectivity and anonymity that emerged from these housing environments for an upcoming mass society.

Supported by the evolution of precast concrete in France, Grandval proposed a system of petal shaped balconies, these gave the buildings their unique appearance, as well as a particular identity, but above all installed a new figure of "screening" the border between the real of the individual and that of the mass,allowing as such as well a visual engagement with the public realm and a high degree of privacy for the individual spatial practices of the occupants: "At Créteil,there was instead a desire to break with the banality of large assemblies. Nevertheless, the surfaces were,for example, very quotas. To compensate, I imagined large balconies. I thought they had to be protected from prying eyes, otherwise they would not be used. This is how I got the idea of these cantilevered petals."[9]

In an attempt to mediate between the strongly mass-oriented approach of the built environment by the French government and the real of the individual Grandval relies on the element of prefabricated concrete balconies. The balconies play a key role in articulating a realm that could negotiate between the societal reality of the greatest number and that of the individual.

Monument and Niche: Ricardo Bofill, Walden

In Spain of the Franco regime thinking about the relation between individual and mass was heavily loaded. The Franco government invested very little in public housing and policies were mainly directed at subsidizing private mortgages with occasionally a few public housing projects.Nevertheless, almost simultaneously to Grandval,the Spanish architect Bofill offered his view on the encounter between mass and individual for the housing project Walden 7 in Barcelona (1970-1975).Bofill redefines this encounter as the field of tension between the monumental scale of mass housing and the individual scale of the inhabitants. Balconies play an important role in this definition. In the Walden housing project the monumentality of the apartment buildings is emphasised by threating them as a closed grossform that is folded into an enormeous urban formation with cavities:

4.5 瓦尔登7号住宅的阳台是反转的壁龛,西班牙巴塞罗那,里卡多·波菲尔,1970-1975/Walden 7 Housing with the balcony as an inverted niche, Barcelona, Ricardo Bofill, 1970-1975.

“立方体和筒仓……我们在这里看到了瓦尔登项目建筑的构成规则,也就是被设计为像北非要塞一样的空间形式,仿佛是一个个立方体堆砌构成的崖面。它在几何层面既是封闭环形的又是分叉形状的。我刻意地在室内空间设计中加强了透视突然反转的眩晕感。目的是让人们对居住空间有非常强烈的体验。”[10]16-17为了表现建筑的宏伟气势,这里加入了完全不同尺度的元素——也就是小体量的半圆形阳台,形成小龛室,它们不仅参与居民的个人生活,也象征着个人与群体社会之间的新关系。对波菲尔来说,阳台作为一种“原型”,能够“帮助克服设计师一时心血来潮想要投身于整个社区的无意识心态,让个人能够加入社会的共同基金[10]164。波菲尔本人对这些建筑元素的原型有一种超现实主义的强烈态度:“楼梯无处可达的悖论,建筑要素悬而未决的荒谬,空间既有力又无用的状态,这一切通过张弛有度的不均衡感、按奇特的比例组合起来,却产生了神奇的效果。”[11]

瓦尔登项目中的阳台就具有这样看似荒谬实则有效的作用。这些阳台既提醒了人们地中海地区长期以室外空间作为起居空间补充要素的传统,又以其面对纪念碑式的住宅建筑体量所展现出的尺度之微小和两相并置的状态,令人们产生了不同的解读方式。这些阳台并不是供人们停留或观赏风景使用的,而且因为面积十分有限,实际上几乎无法实现这些功能,而只是让人们能够出现在阳台上。它让居民能够出现在公共区域,但最重要的是让每位居民个人都能在其身处的群体住宅矩阵中找到自己的位置。瓦尔登项目的室外阳台在体现个性化特征的同时,也表现出在一个大众社会中绝对不可能实现个性化的悖论。

在瓦尔登住宅项目气势恢宏的开敞式室内大厅内,各类形状各异的阳台也占据了空间的核心位置,从小尺度的圆形阳台到半圆形阳台,从更大体量矩形阳台到椭圆形阳台,应有尽有。它们不再和个体的居住环境产生直接的联系,而是和建筑的集体空间产生关联。它们和各种楼梯、廊桥和走廊共同构成了复杂的集体主义交通流线网,且在其中具有特殊意义。它们的作用是要将半集体主义的空间引入瓦尔登住宅项目的室内。这些阳台通过在巨大的集体主义空间内为住户提供小尺度的壁龛空间,供他们长期或短期使用,延伸、补充并打破集体主义建筑体系,表达了群体与个人之间的空间张力。

私人领域的粗暴叠加:白塔,弗朗西斯科·哈维尔·萨恩斯·德·奥伊萨,西班牙马德里,1964-1969

和格兰德沃与波菲尔的例子一样,弗朗西斯科·哈维尔·萨恩斯·德·奥伊萨也通过对现代高层建筑进行欧洲类型学定义的尝试,关注如何表达新的集体主义。萨恩斯·德·奥伊萨想象中的高层建筑,和北美地区那些由层层楼板粗暴叠加构成的大楼有所不同,而是更契合欧洲地中海地区错综复杂的集体主义氛围的建筑类型:“委托方对这一点非常明确,不需要提出一种新形式的社会生活或家庭生活。西班牙的市场和消费者社会早已对此进行了严格的限定。在这种情况下,建筑师只需要为那些为满足‘居住’要求而建立和提出的方案在垂直方向上设计新的组织方式。”1)

在他的“白塔”项目中,阳台在定义这种集体主义的过程中非常重要,它尽可能在两种不同的垂直居住方式之间取得协调,其中一种是“作为物理空间的地理形态在垂直方向上的延伸,使每个人都能与地面保持直接联系……这就是‘城堡式的居住方式’。一座城堡原则上是一种建立在有标志信息的物理空间地理系统上的方式,是另一种地理形态,进一步凸显或强调了它本身。”第二种可能性则是“胶囊式的居住方式”,它是一种在透视关系之外、以非常精巧的方式用玻璃纸包裹起来的居住环境,是悬浮在空中的住宅。常见于这一模型的集体主义关系非常新颖,与前两个例子截然不同——应该从技术、社会学和人文主义的角度对其进行彻底深入的调查[12]。

萨恩斯·德·奥伊萨提出了一种新的类型,介于上述的两个极端情况之间,同时象征了私人空间与当时流行的集体主义形式之间的连结感和分离感。这座完全暴露于室外的混凝土大楼矗立在马德里的天际线上,高达71m。大楼从里到外都表现出其与生俱来的天然有机属性,甚至其墙面也从地面一直无缝延伸到天花板。半圆形的阳台缓和了原始而重复出现的圆形体量相交处形成的尖锐夹角。这些阳台从一侧向另一侧逐层爬升,它们不仅以这种方式形成了体量与光影,组合成非对称感的有趣韵律,也为大楼的不同私人空间形成了彼此连接的关系。

重新洗牌的私密文化:坎迪利斯、伍兹、博迪安斯基,“中心职业发展区”项目,摩洛哥卡萨布兰卡,1952

阳台不仅能代表新的集体主义形象,同时也能代表具有文化意义的居住传统,这可以通过3位在法国执业的建筑师——“建造者工作室”驻非洲办事处的乔治·坎迪利斯、沙德拉奇·伍兹和维克多·博迪安斯基在摩洛哥城市卡萨布兰卡郊区精心设计的项目中得到阐释。19世纪末的法国建筑历史学家皮埃尔·普拉纳在《建筑和施工百科全书》一书中认为“我们从未在亚洲或北非的任何一座穆斯林住宅中观察到对阳台的使用。因为它会完全违背这些族群的习俗,陌生人不可以入侵其生活的私人领域。”[13]对“建造者工作室”来说,在对最新潮的现代居住类型进行定义的过程中,阳台的文化涵化作用在1950年代初期成为其主要的考量因素。

6.7 在“白塔”项目中,阳台是新高层建筑类型中的关键要素,西班牙马德里,弗朗西斯科·哈维尔·萨恩斯·德·奥伊萨,1964-1069/The balcony as a key element of a new skyscraper typology at Torres Blancas, Madrid, Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza, 1964-1969.

(6 图片来源/Source: Efrén Rodriguez ; 7 图片来源/Source:Luis García)

"Cubes and silos ... Here we see the principle of composition of Walden, designed as a casbah in space cubes stacked on top of each other like a rock slant. It is the geometry of the 'O' and 'X'. In the interior, I purposely increased the sheer dizzying,sudden reversals of perspective. I wanted the living space feel very strong."[10]16-17To this grand gesture,a completely different scale element is added: small dimensioned semi-circular balconies that function as little niches that not only play a role in the individual life of inhabitants, but moreover symbolize the new relation between the individual and mass society. For Bofill the balcony is an "archetype" that "overcomes the whim of a designer to plunge the heart of the unconscious of an entire community: it connects the individual to the mutual fund of a society."[10]164Bofill himself holds a particular relation to these archetypical architectural elements an attitude which he describes as surrealist, cultivating: "the paradox of stairways that lead nowhere, the absurdity of elements suspended in the void, spaces both powerfull and useless, whose strange proportions become magical through a sense of tension and disproportion."[11]

The balconies at Walden play this paradoxical role. They appear as elements that remind of a long Medditerenean tradition of outdoor rooms that complement interior dwelling spaces, but their small size and their confrontation with the monumental form of the housing blocks suggest a different reading. These balconies are not places to stay or appropriate, their limited surface makes this virtually impossible, but merely to appear. It allows the inhabitant to appear in the public realm, but above all locates the individual inhabitant within the matrix of mass housing of which he is part. The balconies at the outside of Walden are simultaneously the markers of individuality, and of the absolute impossibility of that individuality within a mass society.

At the spectacular open-air interior lobbies of Walden there is also a central role for balconies which vary in shapes from small circular and semicircular, to larger and rectangular or oval in shape.These balconies are no longer directly connected to the spaces of the individual dwelling, but rather to the collective realm of the building. They are the special parts of a complex network of collective circulation spaces of stairs, bridges and gallery spaces. Their role is to introduce semi-collective spaces within the interior world of Walden. By extending, complementing and punctuating the collective circulation system they represent the field of tension between mass and individual, by offering the inhabitants small niches for short-term or long-term appropriation within the massive realm of collectivity.

A Brutal Layering of Private Domains:Torres Blancas, Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza,Madrid, 1964-1969

Just as in the case of Grandval and Bofil,Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza was concerned with articulating a new collectivity in his attempt to define a European typology for a modern skyscraper.Saenz de Oiza imagined a skryscraper that did not conform to the blunt juxtaposition of floors, as was the case with the North American skyscraper, but rather a typology that was more in tune with the intricate collectivity of Mediterenean Europe: "The client was very explicit on this point: It was not to make a proposal for a new form of social or family life. The Spanish market and consumer society, had,with sufficient rigor defined its requirement. The role of the architect in this case was only to propose a new vertical organisation of those established and supposed program requirements of 'dwelling'."1)

The balcony would play an important role in defining this collectivity in his project for the Torres Blancas, which tried to mediate between two models of vertical living, a first one being "a kind of vertical extension of the topography of the physical space so that no man loses direct contact with the earth...It is the 'castle-dwelling': a castle in principle is a way of imposing on a marked physical topography,another topography that highlights or strengthens it." A second possibility is the "capsule-dwelling":a dwelling environment that is subtly packed with cellophane wrap Out of this perspective, the house floats above the ground. The common collective relations of this model, are very new, very different from the other and the first case: they should be investigated in all of its depth in technical,sociololgical and humanist senses.[12]

Somewhere between the two extremes described above, Sáenz de Oiza suggests a new typology that symbolizes simultaneously the connectivity and separation of private domains into a newfangled collective form. This exposed concrete towers rise 71 metres above the Madrid skyline. Its intrinsic organic nature is carried throughout all aspects of the tower, even the walls flow seamlessly from floor to ceiling. The balconies,which are semicircular in form, serve to soften the sharp angled intersections of the primary circular volumes. They not only jog from side to side as they rise, creating an interesting asymmetrical rhythm of massing and shadow play, but also create relations between the different private domains of the tower.

Shuffled Cultures of Privacy:Candilis – Woods – Bodiansky, Carrieres Centrales, Casablanca, 1952

The balcony was not only a figure of new collectivities but also of the persistence of conventional and culturally-defined dwelling practices,emerges from the project that three French-based architects – Georges Candilis, Shadrach Woods and Victor Bodiansky working for ATBAT-Afrique –elaborated for the periphery of the Morrocan city of Casablanca. While at the end of the 19th century the French architectural historian Pierre Planat inthe Encyclopédie de L'Architecture et de la Constructionhad still claimed that "In not a single Musulman house in Asia or North-Africa we perceive a balcony. This would be completely contrary to the mores of these people in which strangers can not penetrate in the intimacy of life."[13]for the ATBAT the assimilation of this cultural aspect of the balcony would become in the beginning of the 1950s a main consideration in the definition of newfangled modern dwelling typologies.

8 “中心区职业”住宅项目的阳台在建成后很快交给穆斯林使用,摩洛哥卡萨布兰卡,乔治·坎迪利斯、沙德拉奇·伍兹、维克多·博迪安斯基,1952/Carrieres Centrales Housing with the balconies for muslims short after realization,Casablanca, Georges Candilis– Shadrach Woods – Victor Bodiansky, 1952

9 对阳台面向公共区域的不同文化表达方式的研究,摩洛哥卡萨布兰卡,乔治·坎迪利斯、沙德拉奇·伍兹、维克多·博迪安斯基,1952/Studies of the different cultural articulations of the balcony towards the public realm, Casablanca, Georges Candilis– Shadrach Woods – Victor Bodiansky, 1952.

10 “中心区职业”住宅项目的阳台在建成后交给穆斯林使用的现状,摩洛哥卡萨布兰卡,乔治·坎迪利斯、沙德拉奇·伍兹、维克多·博迪安斯基,1952/Carrieres Centrales Housing with the balconies for muslims, Current condition,Casablanca, Georges Candilis– Shadrach Woods – Victor Bodiansky, 1952

(8-10 图片来源/Sources: Woods Archive, Columbia University)

他们当时受到1940年代初著名城市规划师米歇尔·埃科查德的文化主导论启发,正在寻求一种现代的居住形式,使它既能体现居住与生活的进步方式,又能与传统方式保持协调。为了达成这个目标,“建造者工作室”北非办事处的建筑师重点关注了公共领域和私人领域的空间设计,并更精准地着眼于处理两者之间的关系。这种对私人领域和公共空间之间关联特征的强调,最初来源于“建造者工作室”建筑师对偏远地区居住形式进行调查的显著成果,这一成果也被纳入了他们的贫民窟项目中。这些调查强调了在偏远地区的居住环境中,私人与公共空间之间泾渭分明的现场,如何重新出现在了贫民窟的临时建筑类型中。

更重要的是,“建造者工作室”对过渡空间的强调也应该看作是对当时把欧洲高层住宅移植到北非环境后进一步发展的批判。正如布鲁诺·韦西埃所述,在法国战后建筑重建运动中,人们对这些过渡空间设计的关注度和投入度都逐渐减弱[14]。出于居住环境需要理性化的需求,建筑师和工程师在他们住宅设计中逐渐省略了这个空间。韦西埃记录了,像室外平台和连廊这样的过渡性建筑元素如何在战后的法国,尤其是在高密度高层住宅设计的过程中大量消失的过程。

从这个角度看,“建造者工作室”的建筑师在《穆斯林、欧洲、犹太人住宅》(1953)的研究中表现出对位于私人领域和公共区域之间的室外居住空间的强烈关注,是可以理解的。在这个项目里,私人和公共区域之间的关系及其物质载体被认为是居住文化的核心要素。项目探索性地调查了各类室外居住空间的特征及其在个人空间和公共领域之间的过渡作用。“建造者工作室”的建筑师区分了穆斯林住宅、犹太人住宅和欧洲住宅的差别,其中,穆斯林住宅的室外起居空间与私人空间联系非常密切,却与公共区域完全隔离。在另外两类住宅中,公共和私密空间的区隔取决于空间通透程度的不同。

坎迪利斯和伍兹从这些私人与公共区域之间的联系方式出发,为各种独特的居住文化设计了不同的类型。这些不同类型的特点在于在建筑学定义的背景下,私人空间与公共区域、以及和其他相邻空间之间的边界所具有的功能。然而,坎迪利斯和伍兹却认为私人空间和公共区域之间的关系并不只和建筑学的定义有关,他们相信居住行为在其中也有重要的作用:“私人与集体领域之间的关系一次又一次地通过日常行为进行限定,永无止境。”2)

文化交融的场所:费迪南·普永,迪阿·埃尔·马库住宅,阿尔及利亚阿尔及尔,1957

费迪南·普永在其1957年在阿尔及利亚首都阿尔及尔市海滩坡地上设计的迪阿·埃尔·马库住宅项目中表明,阳台也可以被看作不同居住文化模式之间邂逅、对峙或调停的场所。

普永想要建立一处多元文化相互叠加的邻里住宅社区。在他看来,历史上的阿尔及尔强烈地表现出两种不同的文化——土耳其的奥匈帝国文化背景和伊斯兰教统治下的西班牙文化。在迪阿·埃尔·马库住宅中,墙体的纪念性特征令人联想起土耳其的军事壁垒,其内部广场、花园和露台的灵感则汲取自西班牙塞维利亚和格拉纳达的柱廊、喷泉和瀑布景观。建筑师含蓄地表明这些技艺最早来源于法国。

然而,阳台作为建筑元素在其中发挥了协调不同文化的作用,这一特殊的建筑要素成为普永此后偏爱的文化交融场所。这在被称为“图腾塔”的项目里中体现得尤为明显,它由普永和雕塑家琼·阿马多合作设计完成。这座阳台塔楼的不同组成部分表现了普永在阿尔及尔辨认出的各类居住和建筑文化。分布在较低层阳台上的木结构脚手架代表了传统的土耳其住宅。塔楼上楼层较高的阳台装有预制的陶瓷构件组成的面板,代表了现代建筑手法,而形状各异、五彩缤纷的雕塑感元素则来源于更古老的游牧民族居住方式及其装饰要素。

这种把来源于不同建筑传统的建筑构件组合在一起的思想——无论是土耳其式、乡土式还是现代式——都是费迪南·普永现代建筑手法的重要组成部分。他认为现代建筑并不意味着必须引入一套普遍使用的模型,而是意味着“不同的建筑文化和不同氛围彼此相遇,从而共同形成当代境遇下的真实环境。”[15]在迪阿·埃尔·马库的住宅建筑“图腾塔”中,普永说明了这个过程需要艺术家、陶艺家、雕塑家、以及像细工木匠、锁匠和石匠这样充满灵感的手工艺匠共同参与。普永认为,其最终完成的建造仰赖地方手工艺人的参与,不仅能节约成本,也能营造出令居住在这些建筑里的人特别欣赏的建筑特征。

私人文化的层次:宜居的景框,蓬蒂公寓,意大利米兰,1953-1954

吉奥·蓬蒂发现,阳台不仅能表现出居住者的品位,还能成为日常居住生活的场所,由此在重新定义私人领域和城市的公共领域之间关系的过程中起到重要的作用。这位意大利的建筑师因此依据地中海地区的许多窗花、敞廊和凸窗所代表的传统,在住宅和城市的界限之间巧妙地采用了一系列遮蔽要素。

蓬蒂在被称为“宜居的景框”项目中,设计了一种能适应不同居住形式的阳台。它是一套由多层景框、屏风和面板层叠构成的系统,通过日常物件、艺术品和特殊装置,让各种不同的使用方式都能尽情体现在阳台的这幅画布上,并由此细致入微地定义了公共领域和私人领域的各种转换过程。蓬蒂在若干展览中对他这些厚重的阳台进行了探索展示,在其中进一步研究了公共与私人边界的时间特质。结果表明,厚重的阳台不仅能提供各种不同的遮蔽形式,也能够表达和揭示出居住者的身份。很有可能蓬蒂自己也未完全认识到,他已经开始在作品中表达阳台所具有的微观政治维度——通过切实地介入私人与公共领域的边界,在建成环境中为其居住者提供一个主动表现自己的机会。

日常政治场所:安东尼奥·科德奇,萨莉亚的车库住宅,西班牙巴塞罗那,1968-1973

正因为阳台处于个人空间和公共区域之间的关键位置,因此也是一项卓越的政治要素。阳台远远地从高处延伸进公共区域的特征已经让其成为在表现政治权利时备受青睐的建筑元素。阳台是人们表达微观政治观点、演说政治策略和展现参与者的建筑元素,许多政治演说的背景就是阳台,此外它也是一处体现不同微观政治形式的场所。早在1714年,建筑理论家塞巴斯蒂安·勒克莱尔在其《建筑论文:将要投身于这项高贵艺术的年轻人所需的评论和观察》中把阳台形容为:“高高在上的小空间”[16]。

Inspired by the culturalist perspectives of Michel Ecochard, who was the main urban planner of Casablanca in the beginning of the 1940s, they were searching for a way to define modern dwellings that were simultaneously progressive and attuned to conventional ways of dwelling and living. To obtain this the architects of ATBAT-Afrique focused on the design of public and private space, and more precisely on the relation between the two. This emphasis on the character of the intermediate realm between the private and the public was, in the first place, the obvious result of the study of rural dwelling patterns and their transplantation into the bidonvilles that the ATBAT architects performed. These investigations underlined how the strong separation between private and public domains of the rural dwelling re-emerged in the temporary typologies of the bidonvilles.

More important, however, is that ATBAT's emphasis on the intermediate realm should also be understood as a critique of contemporary developments in European models of high-rise housing transplanted into the North-African context.As Bruno Vayssiere illustrated, it can be argued that within French post-war building production there was a decreasing attention and elaboration of this intermediate sphere.[14]Under the guise of rationalization of the dwelling environment,architects and engineers increasingly erased this realm from the housing models they proposed. Vayssi.re documented how in post-war France, especially in the design for dense high-rise housing developments,intermediate architectural elements such as outdoor terraces and galleries largely disappeared.

It is from this perspective that the strong attention for outdoor dwelling space situated in-between the private and the public realm, as shown in the study forHabitations musulmans/européennes/israélites(1953) by the ATBAT architects, should be comprehended. In this project the relation between the private and the public realm and its material manifestation is considered one of the essential aspects of dwelling culture.The project was an exploratory investigation of the character of outdoor dwelling spaces and their role in mediating between the private and the public realm. The ATBAT architects distinguished between Muslim dwellings – where the outdoor dwelling space is in close connection to the private sphere and at the same time completely separated from the public realm – and Israeli and European dwellings.In the last two categories the relation between the public and private sphere is based on different degrees of transparency.

Taking these different relationships between the private and the public realm as a point of departure,Candilis and Woods developed several typologies for particular dwelling cultures. The particularity of the different typologies is a function of the architectural definition of the borders between the private and the public realm and their relation to adjacent spaces. However, Candilis and Woods did not consider the relation between the private and the public realm uniquely a matter of architectural definition, but also believed that dwelling practices played an important role: "The relation between the private and the collective domain is relentlessly defined in everyday practices."2)

Loci of Cultural Metissage:Fernand Pouillon, Diar el-Mahçoul Housing,Algiers, 1957.

That the balcony also can be regarded as the locus for the encounter, confrontation or mediation between different cultural patterns of dwelling was in 1957 illustrated by Fernand Pouillon in his housing project for Diar el-Mahçoul on the slopes of the bay in the city of Algiers. Pouillon wanted to create a housing neighborhood that was culturally multilayered. In his view, historic Algiers expressed the presence of two cultures strongly: Ottoman and Islamic Spain.In Diar el-Mahçoul, the monumental quality of the walls referred to the Ottoman ramparts, whereas the interior squares, gardens, and patios were inspired from Seville and Granada in their porticos, fountains,and cascades. The architect implicitly stated that the technical inventiveness were French.

However, it was the architectural element of the balcony that would play the role of the mediator of different cultures; this specific architectural element would become for Pouillon the preferred locus of a cultural métissage. This becomes particularly clear in the so-called Totem Tower (tour a totem) that was designed together with the sculptor Jean Amado.This tower of balconies is composed of different parts that refer to various dwelling and building cultures that Pouillon discerned in Algiers. The wooden scaffold work in the lower parts of the balconies refer to the architecture of traditional Ottoman housing.The higher balconies of the tower refer with their screen of prefabricated terracotta elements to a modern way of building, while the colorful sculptural elements make reference to tribal patterns and decorations that belong to the old forms of dwelling.

This idea of combining architectural components from various architectural traditions – as well ottoman,vernacular and modern – was very much part of Fernand Pouillon’s approach to contemporary building.In his view modern architecture was not about the import of a universal model, but rather about"an encounter between different building cultures,different atmospheres, that together form the reality of a contemporary condition."[15]In his Totem Tower in Diar el-Mahçoul Pouillon illustrates that this required involvement with artists, ceramists and sculptors,along with inspired craftsmen such as cabinetmakers,locksmiths, stonecutters. Pouillon held that the resulting construction processes achieved a reduction costs because of its reliance on local craftsmanship,but also created features that would be particularly appreciated by those who inhabited the buildings.

Layers of Private Cultures :Inhabitable Viewing Frames, Ponti Apartments,Milan, 1953-1954

That the balcony not only could address the taste of inhabitants, but also could act as a locus of everyday dwelling practices and thus play an important role in the redefinition of the relation between the private realm of the dwelling and the public realm of the city was explored by Gio Ponti. The Italian architect relied therefore on a Meditereneean tradition of subtly screening the border between the house and the city as represented in the multiple mashrabiyas, loggias and oriel windows in the region.

11.12 在迪阿·埃尔·马库住宅项目的“图腾塔”中阳台作为文化融合的场所,阿尔及利亚的阿尔及尔市,费迪南·普永,1957/The balcony as a locus of cultural métissage at Totem Tower at the Diar el Machoul Housing, Algiers,Algeria, Fernand Pouillon, 1957.(图片来源/Sources:Pouillon Archives)

13 阳台的微观政治维度在“宜居的景框”项目中得以体现,德扎大道公寓,意大利米兰,吉奥·蓬蒂,1956-1957/The micro-political dimension of the balcony turned into a project of Inhabitable viewing frames, Via Dezza apartments, Milan,Gio Ponti, 1956-1957.

14 某次展览展出的“宜居的景框”设计原则,吉奥·蓬蒂,1954/Principle of the inhabitable viewing frame (finestra arredata) on an exhibition, Gio Ponti, 1954.

(13-14 图片来源/Sources: Ponti Archives)

战后时期,建筑师安东尼奥·科德奇曾为1962年的罗约蒙特“十次小组”展示了一系列建有阳台的建筑,正是他指出了阳台能够协调环境中的微观政治干预手段的这个特点3)。科德奇认为阳台可以有新的定义,它能依靠“彼此分担的责任,是一片建立在未来使用者共同参与前提下的生境。”[17]科德奇于1960年在《Domus》杂志发表了一篇论文,其中精心阐述了这一建筑思想,文章的标题被故意设为“我们现在不需要天才”。在他为巴塞罗那萨莉亚的车库住宅(1968—1973)所做的设计中,这位西班牙建筑师说明了如何把这一思想体现在设计策略里,他在项目里把阳台当作能够多重兼容的空间。这些基本的建筑造型留有少量的未完成部分,让用户能够根据自己的居住需求进行改造和建造完成,以体现其个性特征。

宏观政治和微观政治的交汇处:阿里耶·沙龙,吉洛住宅,耶路撒冷,1975

毫无疑问,对阳台的微观政治角色做过的最广泛的研究者之一,非以色列建筑师阿里耶·沙龙莫属,他也是一位包豪斯学校的毕业生,他在耶路撒冷南部的一座山坡上设计新建的吉洛住宅项目,其中包括250套不同尺度的公寓。在地缘政治气氛紧张的1970年代,身处以色列的沙龙自然非常鲜明地把他的住宅项目和当时有关居住和建筑的空间实践紧密联系在一起。沙龙的两条主要设计原则来源于所谓的地中海建筑传统和耶路撒冷建筑传统。他以4.5m见方的模数布置住宅平面,这一模数和他在当时耶路撒冷老城和散落周边的阿拉伯村庄中观察到的尺度一致。这个项目的建筑由4.5m宽和2.6m深的模块沿着平面和截面方向堆叠形成。

第二项原则与开敞空间的专门用途有关——如庭院、拱廊、室外台阶和阳台等。毫不夸张地说,这些室外空间就是为新移民以色列的家庭和公民提供的空间。从以色列独立的最初几年开始,住房政策就把移民当作拓荒的公民,基于自助原则为他们提供住房,这也是以自治政府思想作为前提的犹太民族主义核心原则。为新到以色列的移民提供的自助式住房包括国家提供的核心住宅,通常以建筑材料的形式(主要是木料和混凝土块)出现,可供人们自主建造基本的住宅,后期可以由移民根据意愿自行扩建。

吉洛住宅中的阳台响应了这些自治政府和自建房屋的原则,这些原则是以色列民族主义非常核心的思想。它们被认为是单个家庭在其有限的范围内能够完全享有的自由。和他的许多其他规划一样,沙龙认为新来的公民能利用阳台空间积极地建立自己的现代生活方式。然而,阿里耶·沙龙在吉洛住宅中实行的最激进的决定却并未把阳台的私人空间和集体区域完全分隔开。现实完全相反,每套公寓都有阳台,而通过从地面一直爬升到屋顶通道的室外楼梯总会经过其中一两个阳台。在私人空间和集体空间之间设置这样直接和彻底的接触方式表明,在沙龙的设想中,自治政府和自建房屋根本不是所谓的“个人主义”或甚至“无政府主义”。自建房屋的思想被当成人们正在集体成就的更宏大项目的一部分,并且在本质上,最重要的是彼此合作。

把阳台当作自建房屋的场所也要求人们对现代建筑要素的变形能力进行反思。在吉洛住宅中,把自建房屋的思想理解为对原有平面的扩建。如果是这样,那么居住者对某项建筑元素进行改造的行为,并不能代替人们在废墟中搜寻旧物件的轻度实用主义普遍观念,却完全有可能把每一次对原始平面和原始形式的反应都理解为它们可以构成其自身的普世主义宣言。

阳台的美丽新世界2020

通过对战后建筑文化中的阳台要素的回顾,揭示出了人们试图重新夺回阳台所具有的一系列文化、社会和政治力量的相关理论与实践。尤其是整个地中海地区,从西班牙、法国和意大利,到以色列、阿尔及利亚和摩洛哥,阳台作为建筑元素似乎已经成为需要在不同条件和文化背景下不断进行修正、同化和融合的对象。

阳台不仅仅是建筑师需要关心的元素,2020年新冠病毒肆虐全球,这一点变得显而易见。为了控制新冠病毒的蔓延,从2020年3月开始许多市民被建议待在自家的私人空间内。在国家公权力前所未有地侵入日常生活的背景下,市民被限制使用公共区域,并且把公共接触减少到最低程度。像“居家隔离”和“保持社交距离”这样的口号已经成为城市日常话语的一部分。4)

幸好,在当代社会,人们并不能理所当然地接受切断公民与社会生活和公共区域联系的要求。相反,公民会想方设法接近公共社会,包括用其他方式团聚,采用其他的策略进行分享、照顾和提供支持,也就是说用各种不同的方式实现共惠共享。虽然数字科技提供了一套全新的渠道和模式进行碰面、交流与合作,但在模拟信号的世界、在欧洲的邻里社区和城市中,人们也发明了新的沟通方式。其中扮演了关键角色的一项城市要素就是阳台。

在2020年初的几个月,阳台在人们的日常生活中获得了新的意义和重要性。首先,阳台为人们提供了不需要真正进入公共空间就可以在其中出现的方式。许多人在阳台提供的安全空间里参与城市生活。无论是注视过往的行人还是和邻居聊天,多亏有了阳台的安全空间,这些行为才有可能继续。其次,阳台也成为一个人能够进入露天环境、同时又与他人保持距离的室外空间。人们为现在的阳台创造了许多新的使用方式。人们在阳台上玩游戏、做运动、冥想等等。第三,阳台也重新获得了作为政治空间的地位。在新冠病毒流行期间,人们希望自己的政治呼声能被听见,包括他们对政治决策的失望,或他们对面临危险境况的医务工作者的支持等话语。公众能通过阳台的城市空间进行表达——人们在阳台上挂出条幅,或只是在一天中特定时刻以拍手的方式来表达政治观点。

摩洛哥社会学家弗朗西斯科·纳韦斯-布沙尼纳认为阳台是“接壤空间,‘过渡的空间’,是室内与室外、公共与私人之间类似门锁的存在,它们是‘正当其所的场所’”[18]。纳韦斯-布沙尼纳指出这些接壤空间能够“保持距离”,并且因此其含义和使用将不可避免地与室内与室外、公共与私人空间之间的过渡、转换和决裂产生关联。纳韦斯-布沙尼纳写到,接壤空间的特点是建筑内外的相互对立,室内与室外的通道别有意味,以及开敞与封闭之间复杂的挑战关系。

In his project for so-called "inhabitable viewing frames" Ponti develops a balcony arrangement that can accommodate different forms of inhabitation. It is a layered system of frames, screens and surfaces that offers a canvas on which various forms of appropriation – through everyday things, art objects and special installations – could be projected and thus define nuanced transitions between the public and the private realm. Ponti experimented with his thick balconies in several exhibitions in which the temporal character of the border between public and private was further investigated. These illustrated that the thick balcony not only offered the possibility of various ways of screening but also for articulating and exposing the identity of the inhabitant. Most likely without fully realising, Ponti started to address in his projects the micro-political dimension of the balcony – pointing to its capacity to offer the inhabitant an active role in the built environment through concrete intervention at the edge between the private and the public domain.

Sites of Everyday Politics:

Antonio Coderch, Viviendas de las Cocheras de Sarrià, Barcelona, 1968-1973

Because of its crucial position between private and public realms the balcony is a political element par excellence. Its elevated outreach to the public realm has turned the balcony into a preferred architectural element for the exercise of political power. The balcony is the architectural element on which the macro-political viewpoints, strategies and actors are represented, as being represented by the many political speeches thawere given from balconies, but it is also a site of various forms of micro-politics. Already in 1714 the architectural theoretician Sebastien Le Clerc described in hisTreatise of Architecture: With Remarks and Observations Necessary for Young People Who Would Apply Themselves to That Noble Art.the balcony as "une petite place élevée en l'air."[16]

In the post-war period it was the Spanish architect Antonio Coderch, who presented a collage of a balconized structures to the Team 10 Royaumont meeting (1962) to point to this particular aspect of the balcony: its capacity to accommodate micro-political intervention in the environment.3)Coderch looked upon the balcony as a site that could contribute to a new definition of architecture that would rely on a "sharing of responsabilities, habitat based on the participation of the future user."[17]Coderch had elaborated this idea of architecture as a matter of co-production in a 1960 article forDomus, which he provocatively entitled "We do not need geniuses right now". In his proposal for the Viviendas de las Cocheras de Sarrià in Barcelona (1968-1973) the Spanish architect illustrates how this can be implemented in a design strategy. In this project the balconies are understood as polyvalent spaces. Basic architectural figures that are left slightly unfinished so that users could adapt and complete the spaces to suit their dwelling needs and reflect their individual personalities.

Places of Encounter Between Macro- and Micro-politics:Arieh Sharon, Gilo Housing, Jerusalem, 1975

One of the most pervasive investigations of the micro-political role of the balcony was beyond doubt given by Israeli architect and Bauhaus graduate Arieh Sharon in his design for the new Gilo housing comprising 250 apartments of various sizes located on a hill south of Jerusalem. In the charged geopolitical climate of 1970s Israel it is no surprise that Sharon explicitly related his housing project firmly to the existing spatial practices of dwelling and building. Sharon bases his projects on two principles evolved from so-called Mediterranean and Jerusalem building traditions. He conceives his housing on a repetitive modular grid of 4.5 metres,a module that he discovered in existing structures in the Old City and in the free packing of the Arab village. In this project the buildings are staggered in cross-section as well as in plan by modular packing of 4.5 m width and 2.6 m depth.

A second choice relates to the specific use of open spaces: courtyards, arcades, outside steps and balconies. These outside spaces were literally considered as domains that were offered to the new families and citizens of Israel. Housing policies had,from the first years of independence, looked upon immigrants as pioneer citizens that were provided housing based on the principle of self-help, a core principle of Jewish nationalism premised on the idea of self-governance. The self-help housing options available to immigrants upon arrival in Israel included core housing provided by the state, which often took the form of building materials (primarily timber and concrete blocks) for auto-construction of basic dwellings which might later be expanded through the initiative of the immigrants themselves.

15在罗约蒙特“十次会议小组”上展示的一幅布满了阳台的建筑拼贴画,安东尼奥·科德奇,1962/Collage of a balconized structure presented at Team 10 meeting in Royaumont, Antonio Coderch, 1962.

16 阳台缓和了建筑边缘,萨莉亚的车库住宅,西班牙巴塞罗那,安东尼奥·科德奇,1973/The balconies are part of the frayed edges of the buildings at Viviendas de las Cocheras de Sarrià, Barcelona, Antonio Coderch, 1973.

17.18 吉洛住宅的阳台是使用的领土,耶路撒冷,阿里耶·沙龙和艾尔达·沙龙,1975/Gilo Housing with the balconies as a territory of appropriation, Jerusalem,Arieh Sharon and Eldar Sharon, 1975. (图片来源/Sources: www.ariehsharon.org)

除了对过渡功能的诉求,接壤空间的另一个特点也包含了一项简单的事实,也就是说它们是“附加”给其他空间的。他们具有附属的特点,并且与其他空间拥有共同的边界。阳台的这种双重面向为这一元素提供了独特的语义负荷。一方面,阳台因为具有介于两者之间的特点,似乎是非常有张力的建筑元素。它们能在不同建筑元素之间、不同区域和空间之间协调一致,并因此获得高浓度的语义负荷。它有成为一种连接形式的潜质,可以成为补充要素或反义要素,它像一个过门。另一方面,阳台也是一种释放语义负荷的形式。它的附属特征暗示了阳台相对于其他的建筑空间而言具有某种中立性质,它能够适应许多不同的空间活动,可以在更广泛的背景下进行解读。

正是因为阳台具有这些边界接壤的特征,使它在所有其他城市要素中获得了一席之地。最近新冠病毒的经验表明,在我们的城市里存在对于接壤空间的需求,所以,阳台的传奇应该成为当代建筑实践与思想的“秩序维持要素”。阳台应该开始恢复为成熟的建筑元素,参与到它的文化、社会和政治语义负荷之中。

The balconies in the Gilo housing were thought to echo these principles of self-governance and selfbuilding that were so central to Israeli nationalism.They are conceived as free-zones that can be within their limits fully appropriated by the single families.Just as in many of his other plans Sharon held that the new citizens could use the domain of the balconies to actively fashion a modern life-style of their own.However, the most radical decission of Arieh Sharon in the Gilo housing is that the private domains of the balconies are not separated or excluded from the collective realm. Quite on the contrary. The access to the different balconies is by external stairs that climb from ground-level to the roof passing through one of the two balconies, with which each apartment is provided. This figure of a direct, radical encounter between private and collective domains, illustrates that in Sharon's vision the self-governance and self-building is not related to what elsewhere is called "individualism" or even "anarchism".The idea of self-building is regarded as part of a bigger project which is carried by the collective and is first and foremost cooperative in nature.

The idea of looking upon the balcony as site of self-building also invites for a reflection on the transformative capacity of modern architectural elements. In the Gilo housing the idea of self-building is defined as an extension to the initial plan. Taken this way, the repurposing of an architectural element by its inhabitants does not replace a universalist conception with a kind of small-scale pragmatism of a withered subject picking through the wreckage, but rather opens up an entirely new field of possibility in the understanding that each response to the initial plan and form constitutes its own universalist claim.

The Balcony Anno 2020

Looking at the balcony in postwar architectural culture reveals an image of practices and discourses that attempt to recapture the particular cultural,social and political charge of the balcony. Especially across the Mediterenean, from Spain, France and Italy to Israel, Algeria and Morocco, the architectural element of the balcony seems to have been the constant subject of revisions, of assimilations and acculturations to specific conditions and cultures.

That balcony is not only a concern for architects became clear in 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit the world. As part of the attempts to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic, many citizens were from the beginning of March 2020 advised to permanently remain within the private domain of their home. In an unprecedented intrusion of the State in everyday life,citizens were required to restrict their use of public space as well as their public interactions to the bare minimum.Slogans as "confinement" and "social distancing" became part of the ordinary discourse on the city.4)

Dissociating citizens from social life and from the public sphere is, fortunately so, in contemporary societies not an idea that is docilely accepted. On the contrary, citizens have searched for alternative ways to appear in public, for other modes of meeting one another, for other tactics to share, care and support– for different ways of commoning. The digital sphere has offered a panoply of new channels and modes of encounter, exchange and collaboration, but also in the analogue world, in the neighborhoods and cities of Europe, alternative ways of doing were developed.One urban element has played a key role: the balcony.

In the first months of the year 2020 the balcony gained a new meaning and importance in every day life and this from multiple perspectives. First, the balcony offered a way to appear in public space without being litterally immersed in it. Many people observed and participated in urban life from the safe space of the balcony. Watching the passers-by or engaging in a talk with your neighbours remained possible thanks to the safe space of the balcony. Second, the balcony became also an exterior space where one could be outside, in the open air, but nevertheless distance from others.Many new appropriations of existing balcony came into being. People were playing games on balconies,were doing sports, were meditating and so on. Third,the balcony was also recaptured as a political space. In times of COVID people wanted to make their political voices hear, about their disappointment with political decision-making or their support for care workers dealing with his precarious situation. The balcony was the urban space from which these public could be articulated: people were hanging banners on their balconies, or simply clapping their hands at the certain moments of the day to express their political opinion.

The Moroccan sociologist Françoise Navez-Bouchanine has qualified the balcony as a "limitrophic space [that]is an 'intermediate space', a sort of lock between the inside and the outside, between the public and the private, these are 'places in-their-own-right'."[18]Navez-Bouchanine points out that these limitrophic spaces have the capacity ‘to create distance’ and thus that their meaning and appropriation is inextricably related to the transitions, shifts and ruptures between inside and outside, between public and private space. Limitrophic spaces are, writes Navez-Bouchanine, characterised by a charged play between inside and outside, by the loaded passage between interior and exterior, by the complex challenges of opening and of closure.

Nexto this mediating appeal, limitrophic spaces are also characterised by the simple fact that they are "added to" other spaces. They have an auxillary character and are bordering other spaces. This janusfaced character of the balcony offers the element a particular semantic load. On the one hand, the balcony seems to be an architectural element that is fully charged because of its in-between character. The balcony mediates between different other architectural elements, between realms and spaces, and receives therefore a dense semantic load. It is charged with the potentiality to be a connector, a complement or even an antipode; it appears as a threshold. On the other hand, the balcony is a figure of discharge. Its auxillary character implies that the balcony holds a certain neutrality vis-à-vis the rest of the building, that it can accommodate a variety of spatial practices, that it is available for a broad horizon of interpretations.

It are these limitrophic characteristics, that offer the balcony such a specific place between all other urban elements. The recent experiences with COVID-19 illustrate that there is a need for limitrophic spaces in our cities and thus that the saga of the balcony should be a "rappel a l'ordre" for contemporary architectural practice and thinking.It is an invitation to start reclaiming the balcony as full-fledged architectural element and thus engage with its cultural, social and political charge.

译注/Note from Translator

i 卡尔·马克思大院是奥地利维也纳的一座著名大型公共住宅 ,位于第19区德布灵的海利肯施塔特社区。卡尔·马克思大院长达1100m,跨4个路面电车站,是世界上最长的单体建筑。

注释/Notes

1)“委托方对这一点非常明确,不需要提出一种新形式的社会生活或家庭生活。西班牙的市场和消费者社会早已对此进行了严格的限定。在这种情况下,建筑师只需要为那些为满足‘居住’要求而建立和提出的方案在垂直方向上设计新的组织方式。如果读者要想在我们的方案中找到超出我们所提供的内容,我们会温和地提醒他,他可能不可避免地产生自相矛盾。白塔并不是为了创造新的房间形式创作的,而是为了以新的方式把房间垂直地纳入空间之中。”/"The client was very explicit on this point:it was not a question of making a new proposal for a social or family way of life. The Spanish market, and its society of consumers, had, with sufficient rigor defined its demand. The role of the architect in this case was only to propose a new vertical organisation of those established and supposed programmatic demands of 'living'. If the reader wants to find in our proposal more than what we offer, we gently warn him about his possible and inevitable contrariness. Torres Blancas was not intended to be a new form of room but a new way of vertically inserting the room into space."https://etsav.upc.edu/ca/escola/serveis/biblio/oiza/documents/cuadernos.pdf

2)乔治·坎迪利斯. 穆斯林、欧洲和犹太人住宅.未出版文字,坎迪利斯/IFA, (318/7),1953,2.原文引自法语/ Georges Candilis. Habitations musulmans/européennes/israélites. unpublished project text, in:Candilis/IFA, (318/7), 1953, 2. Quote in French: La relation entre le domaine privé et collectif est aussi bien définie dans les pratiques quotidiennes.

3)更深入的讨论请见《蓝色广场》第4期,1962 /For a discussion of this contribution, see Le Carre Bleu,no. 4, 1962.

4)意大利哲学家乔治·阿甘本的相关论述详见[2020-04-14].http://autonomies.org/2020/04/giorgioagamben-social-distancing/See in this respect the writings of Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben.[2020-04-14]. http://autonomies.org/2020/04/giorgio-agamben-social-distancing/