Genetic variation and phylogenetic relationship of Hypoderaeum conoideum (Bloch, 1782) Dietz, 1909 (Trematoda: Echinostomatidae) inferred from nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequences

2020-10-19ChairatTantrawatpanWeerachaiSaijuntha

Chairat Tantrawatpan, Weerachai Saijuntha

1Division of Cell Biology, Department of Preclinical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, Rangsit Campus, Pathumthani 12120, Thailand

2Walai Rukhavej Botanical Research Institute, Mahasarakham University, Maha Sarakham 44150, Thailand

ABSTRACT

KEYWORDS: Echinostomes; Genetic diversity; Genetic differentiation; Nuclear ribosomal DNA; Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1; NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1

1. Introduction

Hypoderaeum (H.) conoideum (Bloch, 1782) Dietz, 1909 is a species of digenetic trematode in the family Echinostomatidae, which is the causative agent of human and animal echinostomiasis[1,2]. The life cycle of H. conoideum has been extensively studied experimentally[3,4]. A wide variety of freshwater snails, especially the lymnaeid species, are the first intermediate hosts and shed cercariae[5]. Aquatic animals, such as bivalves, fishes, and tadpoles, often act as second intermediate hosts. Eating these raw or partiallycooked aquatic animals has been identified as the primary mode of transmission[1,6]. It has been noted that wild rats, chickens, ducks, and geese may be infected and then consumed[7-9]. Heavy infection of H. conoideum was observed in free-grazing ducks in Thailand and Lao PDR[8], and there have been reports of human echinostomiasis in Thailand[10,11].

To date, at least four medically important echinostome species have been documented in Thailand: Echinostoma (E.) revolutum (Froelich, 1802), E. ilocanum (Garrison, 1908), Artyfechinostomum (A.) malayanum (Leiper, 1911) Mendheim, 1943, and H. conoideum. However, as the eggs of all these echinostomes are morphologically very similar, there is extreme difficulty in differential diagnosis[12]. Thus, several molecular markers/techniques have been developed to solve this problem[12-15]. Molecular markers such as allozymes as well as nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequences have been effective in the genetic study of echinostomes[13,14,16,17]. Nuclear ribosomal DNA, mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (CO1) and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 (ND1) have been widely used to explore genetic variation of echinostomes[15]. CO1 and ND1 sequences were used to differentiate E. revolutum and E. miyagawai infections in free-grazing ducks[15]. Recently, species-specific reverse primers have been designed to target different ND1 fragment sizes in multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to differentiate four echinostomes[12].

Previous reports demonstrate that the genetic variations present in these echinostomes play an important role when developing these molecular markers/techniques. While comprehensive genetic investigation has been undertaken in some species, e.g. the “37 collar-spined” or the “revolutum” group including E. miyagawai and E. revolutum[13,15,18], there have been few similar investigations into H. conoideum. To our knowledge, very few published reports of genetic investigation into H. conoideum, e.g. mitochondrial genome sequencing[19] and genetic differentiation from E. revolutum[16], outlined possible phylogenetic relationships with some species of the family Echinostomatidae using nuclear DNA sequence and karyological analysis[14,20]. Therefore, our study aims to use nuclear ribosomal DNA (ITS), mitochondrial CO1, and the ND1 gene to explore H. conoideum genetic variations in domestic ducks from Thailand and Lao PDR.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample collection and DNA extraction

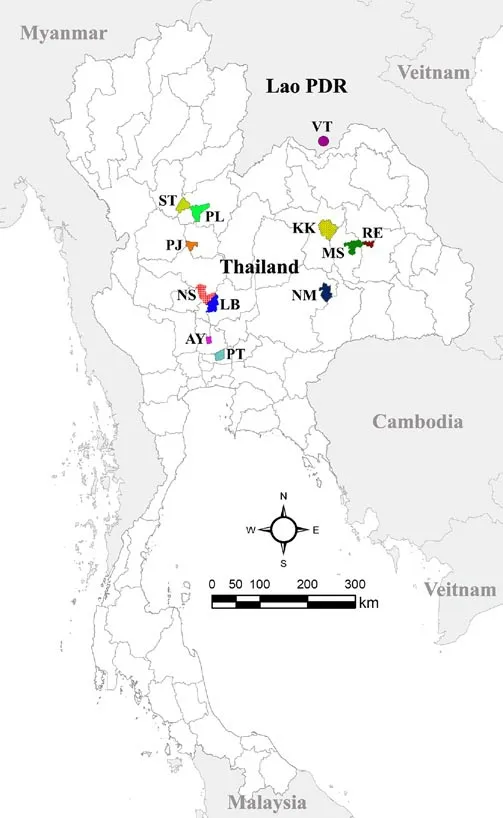

Duck intestines were purchased from local slaughterhouses in several localities around Thailand and from one location in Vientiane, Lao PDR (Table 1 and Figure 1). The intestines were then opened to retrieve adult H. conoideum. The adult worms were identified by flattening them between two glass slides, held apart by a small piece of filter paper, and then examined under a light microscope. Species were identified based on elongate-shaped testis, presence of small collar and 45-53 collar-spines[21]. Adult worms were then washed several times in normal saline before being fixed in molecular grade ethanol and stored at –20 ℃ until use. A single worm was placed into a 1.5 mL vial, and the alcohol removed by vacuum centrifuge. Then an E.Z.N.A.®Tissue DNA kit (Omega Bio-tek, USA) was used to extract DNA following the manufacturer’s instructions. The biosafety ethics for this research were approved by the Institute Biosafety Committee of Thammasat University: 173/2561.

Table 1. Sample collection localities in Thailand and Lao PDR.

Figure 1. Map of sampling localities. More details of the locality codes are shown in Table 1.

2.2. PCR and DNA sequencing

To amplify the DNA target regions, PCR was performed using primer pairs of ITS1F (5’-GGTGAACCTGCGGAAGGATC-3’) and ITS2R (5’-AGCGGGTAATCACGACTG-3’) for ITS1-5.8SITS2 fragments[22]. The primers for CO1 and ND1 amplification are current design and use in this study, namely Hcon-CO1F (5’-GATGCCGGTGTTGATTGGTG-3’) and Hcon-COR (5’-CACACAAACCCGACGAGGTA-3’) for CO1, Hcon-ND1F (5’A TTCTGCTTACTTAGTTTTGAGGAG-3’) and Hcon-ND1R (5’-TAATCATAACGAACCCGAGGTAAC-3’) for ND1. For all DNA fragment amplification, PCR was performed in 25 µL, including approximately 100 ng of template DNA, 1 µL of each primer (each 10 pmol/µL), 2.5 µL of 10× Ex-Taq buffer (Mg2+plus), 2 µL dNTPs (each 2.5 mmol/L), 0.125 µL of Ex-Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/ µL), and 19.375 µL of deionized water. PCR employed an initial denaturing step at 95 ℃ for 4 min, 35 cycles of denaturing at 94 ℃ for 40 s, annealing at 50 ℃ for 60 s, extending at 72 ℃ for 60 s, and a final extending step of 72 ℃ for 8 min. PCR products were separated into 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and visualized with GelRedTMNucleic Acid Gel Stain (Biotium, Inc., Hayward, CA). The amplified bands were cut and purified using E.Z.N.A.®Gel Extraction kit (Omega Bio-tek, USA) and subsequently sequenced at 1st BASE Laboratories, Malaysia.

2.3. Data analyses

The sequences were checked and edited using ABI sequence scanner v1.0 and BioEdit v7.2.6[23] software. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using the ClustalW program[24]. Genetic diversity indices, including segregated sites, haplotype number, haplotype diversity, and nucleotide diversity, were computed and generated by DnaSp v5 software[25]. Median joining haplotype networks[26] were generated using Network v.5.0.11 (http://www.fluxus-engineering.com) based on CO1, ND1, and ITS sequences. Phylogenetic relationship was performed based on ND1 sequences of H. conoideum from different localities in Thailand and Lao PDR, as well as a sequence of H. conoideum from Hubei, China, including Hypoderaeum sp. from America and Europe available in GenBank. The maximum likelihood and neighbor joining trees were performed using MEGA X[27] with nodal support estimated using 1 000 bootstrap re-sampling.

3. Results

The new sequences generated in this study were deposited in GenBank with the accession numbers MT127126 to MT127176, MT159471 to MT159526 and MT175378 to 175434 for the partial sequences of ITS1-5.8S-ITS2, CO1 and ND1, respectively. In the case of ND1, the 820 bp fragment was successfully amplified, but only 522 bp were readable and reliable for analyses after DNA sequencing. As the variable sites of ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 were found in the ITS1 and ITS2 regions. Although all samples underwent PCR to amplify all three DNA regions, some were not successfully amplified or did not provide reliable DNA sequencing results in all regions. Thus, we have an unequal number of samples examined in each locus (Table 2).

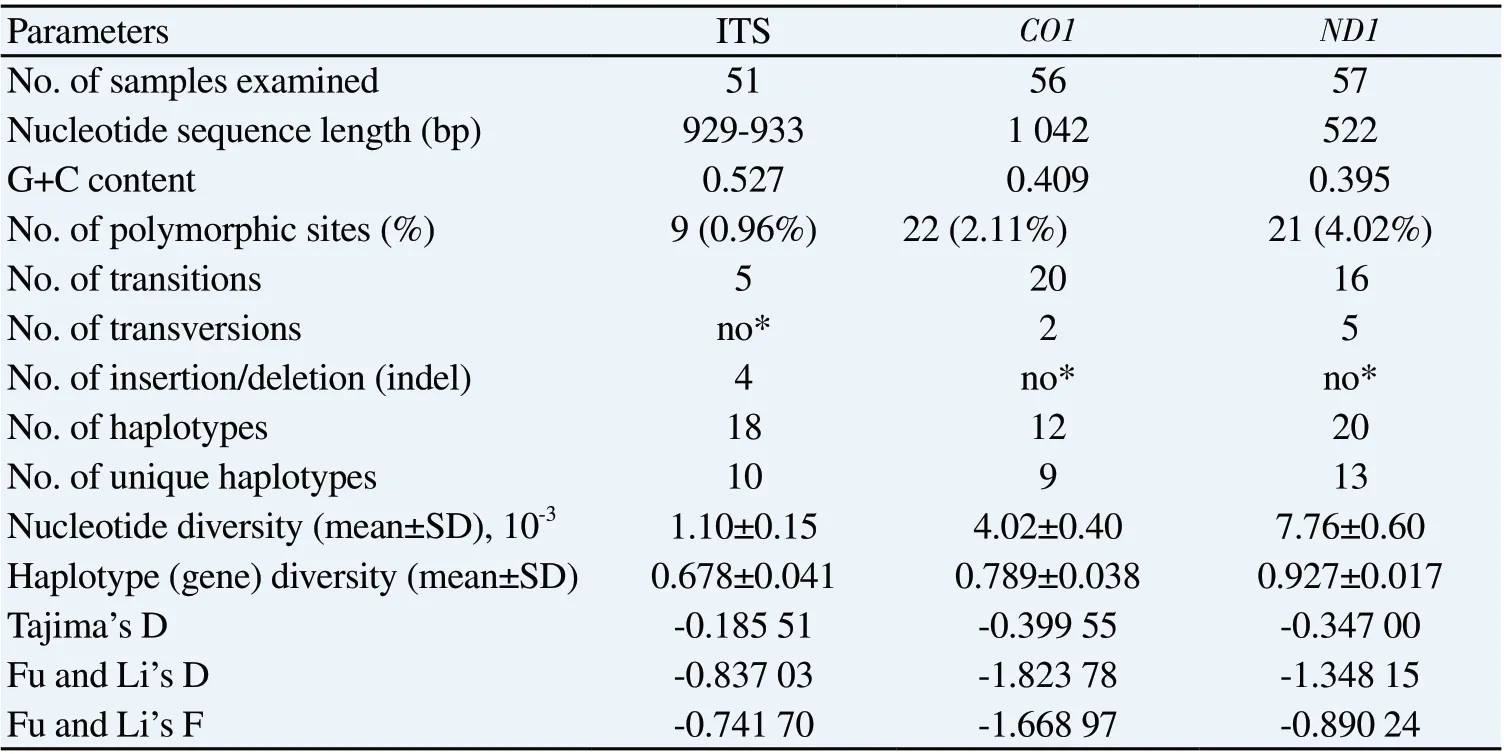

Molecular diversity index comparisons between three loci found that ND1 had the highest nucleotide polymorphism with variable nucleotide sites at 4.023%, whereas CO1 and ITS sequences had 2.111% and 0.964%, respectively (Table 2). Of these variable sites, nucleotide transition was most commonly observed in all three DNA regions, whereas nucleotide transversion were only occasionally present in CO1 and ND1 genes. Insertion/deletion (indel) was only visible in the ITS regions at four nucleotide sites (Table 2). Nucleotide and haplotype (gene) diversity were observed at (0.007 76 ± 0.000 60) and (0.927 ± 0.017) for ND1, (0.004 02 ± 0.000 40) and (0.789 ± 0.038) for CO1, (0.001 10 ± 0.000 15) and (0.678 ± 0.041) for ITS sequences analyses. Neutrality analysis found that negative values were observed in all Tajima’s D, Fu and Li’s D, and Fu and Li’s F calculations (Table 2), revealing an excess of rare alleles due to a recent population expansion. There were 20 haplotypes of ND1, 12 of CO1, and 18 of ITS; of these, 13 ND1, 9 CO1, and 10 ITS haplotypes were unique to a particular locality (Table 2). Several common haplotypes were networked between different localities, such as haplotypes C1, C2 and C10 for CO1; haplotypes I6, I3, I12, I15, I16 and I17 for ITS; haplotypes N1, N6, N7 and N14 for ND1 (Figure 2).

Table 2. Molecular diversity indices and neutrality test of ITS, CO1 and ND1 sequences in the Hypoderaeum conoideum populations from Thailand and Lao PDR.

Figure 2. Haplotype networks constructed from CO1 (A), ITS (B) and ND1 (C) sequences. Each circle represents a haplotype named with a different number. Different printed patterns in the haplotype networks correspond to their geographical localities separated into 12 different localities.

Phylogenetic tree constructed based on ND1 sequence (Figure 3) demonstrated that the genetic structure of H. conoideum is related to continent geographical scale and defined into three different lineages supported by high bootstrap values. All samples from Thailand and Lao PDR were closely aligned with a sequence of H. conoideum from Hubei, China and defined as Asian lineage. Whereas the Hypoderaeum sp. ND1 sequences from USA and Canada were monophyletic group as American lineage and closely aligned with two sequences from Spain which was classified as European lineage (Figure 3).

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to use three genetic markers including two mitochondrial genes, i.e. CO1 and ND1, and nuclear DNA sequences, i.e. ITS1-5.8S-ITS2, to explore genetic variations in H. conoideum recovered from domestic ducks in Thailand and Lao PDR. Nucleotide polymorphism of H. conoideum was detected at all the loci examined. The mitochondrial ND1 sequence revealed the highest polymorphism and was most suitable for use as a genetic marker to explore H. conoideum genetic variations, as also previously reported in the genetic variation investigations of the “37 collar-spined” or the “revolutum” group of Echinostoma[13,15]. Some combination of all three loci incorporated within our study could potentially be of great use for further genetic investigation of this parasite, which is endemic worldwide.

We found a high amount of genetic variation in H. conoideum populations from the different geographical localities. We found many common or shared haplotypes of H. conoideum in Thailand and Lao PDR. This indicates there has clearly been some gene flow among the populations between these two regions. This may have occurred as farmers in both areas feed their free-grazing ducks on naturally occurring snails by rotating them among rice paddies in Thailand[8,15]. It is likely the same in Lao PDR[15].

As expected, there was no genetic sub-structuring related to different regions in Thailand and Lao PDR observed in our study. However, there were reports of geographically influenced genetic differentiation within E. revolutum and E. miyagawai at the continental scale, such as in the Americas and Australia; isolates from Europe and Southeast Asia are defined as the Eurasian population[15,18]. We found that the lineages of H. conoideum and Hypoderaeum sp. were difference at a continental scale by separated into American, European and Asian lineages supporting the previous reports of genetic structured of the 37 collar-spined echinostomes[15,18].

Genetic variations of H. conoideum populations in Thailand and Lao PDR may potentially be caused by several factors, such as specialization of infecting different species of intermediate and final hosts. Many aquatic animals can act as intermediate hosts, and the final hosts could be birds, rodents or other mammals, including humans. The various species or cryptic species of snail intermediate hosts located in a particular area may contain differently adapted genotypes/haplotypes. As previously reported, a unique haplotype based on the ND1 sequence was noted in A. malayanum recovered from different snails acting as intermediate hosts[28]. Moreover, temporal factors such as seasonal/climatic variations may also have influenced the genetic differentiation and sub-structuring of H. conoideum populations. Previous evidence of the genetic differentiation in E. revolutum populations from the same locality in Thailand related to temporal factors was reported[17]. To facilitate more understanding of the population genetics and structure of this parasite, H. conoideum samples should be collected from different intermediate/final hosts as well as at different times of year in a particular locality and then genetically analyzed.

In Southeast Asia, there is still a high prevalence of echinostome infection in humans, particularly in Lao PDR, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand[1,2,29,30]. Co-endemic and mixed infection of echinostomes, e.g. H. conoideum and E. revolutum in duck hosts[8] or H. conoideum and A. malayanum in rodent hosts (Ribas et al, unpublished) have been observed. All of these previous studies have identified echinostome specimens solely based on morphology; in a recent report, however, multiplex PCR, based on species-specific reverse primers and targeting variable regions of the ND1 gene, was able to differentially diagnose human echinostomes in Thailand[12]. Other mitochondrial genes could also be used to specifically detect E. revolutum metacercariae in their snail hosts[18,31]. The basic information of nucleotide sequence variations from our study can be applied in the molecular diagnosis/detection of H. conoideum as well as other medically important echinostomes. It would be worthwhile to attempt the molecular identification of future human echinostomiasis cases in Southeast Asia. Not only would this increase our understanding of the host-parasite life cycle, but it may hopefully provide us with valuable information on how to interrupt its maturation and, thus prevent future infestations in intermediate and human hosts.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Adrian R. Plant for English proofreading.

Funding

This research was supported by Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, Thailand to CT, grant number 2-18/2562.

Authors’ contributions

CT and WS contributed equally to this article and read and approved the final manuscript.

杂志排行

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- Convalescent plasma: A potential therapeutic option for COVID-19 patients

- Clinical outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis C after generic direct-acting antiviral treatments in Vietnam: A retrospective analysis

- Phytochemical profiling and biological activity of Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour.) mediated by various solvent extracts against Aedes aegypti larvae and toxicity evaluation

- Effect of climate change on spatial distribution of scorpions of significant public health importance in Iran

- ARIMA models forecasting the SARS-COV-2 in the Islamic Republic of Iran