Convalescent plasma: A potential therapeutic option for COVID-19 patients

2020-10-19SweeLiNgTsueyNingSoonWeiHsumYapKaiBinLiewYaCheeLimLongChiauMingYinQuanTangBeyHingGoh

Swee Li Ng, Tsuey Ning Soon, Wei Hsum Yap, Kai Bin Liew, Ya Chee Lim, Long Chiau Ming, Yin-Quan Tang✉, Bey Hing Goh,

1Biofunctional Molecule Exploratory Research Group (BMEX), School of Pharmacy, Monash University Malaysia, Bandar Sunway, Malaysia

2School of Biosciences, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, Taylor’s University, Subang Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia

3Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Cyberjaya, Cyberjaya, Selangor, Malaysia

4PAP Rashidah Sa'adatul Bolkiah Institute of Health Sciences, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Gadong, Brunei Darussalam

5College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, P. R. China

ABSTRACT

KEYWORDS: Coronavirus; Convalescent plasma; COVID-19; SARS-COV-2; Neutralizing antibody; Immunomodulation; Convalescent plasma transfusion

1. Introduction

It is unfortunate that the 2020s decade began with the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic outbreak spreading globally. Several studies are pointing to the evolutional origin of SARS-CoV-2 from Malayan pangolins (Manis javanica)[1,2]. This specific pangolin species is natively originated from Southeast Asia and could be found in Myanmar, Lao PDR, Thailand, Malaysia, Sumatra, Java, Indonesia, Cambodia, Vietnam and Brunei. Lam et al. revealed that the specific receptor binding domain of pangolin-CoV that binds to human ACE2 for its entry, together with their recombination with bat-CoV-RaTG13-like virus might explain the¬emergence of SARSCoV-2 which threatens the health of human population[1-3].

Since December 2019, the outbreak of COVID-19 has resulted in over 6.4 million cases of infection along with more than 380 000 deaths as of June 3, 2020. These numbers are expected to rise continuously as there is no approved treatment nor vaccine to stop this pandemic at the moment. Symptomatic patients may experience fever, cough, shortness of breath and pneumonia after exposing to the virus within two to fourteen days. These symptoms may range from mild, moderate to critical or severe, while some patients may not show any symptoms. Elderly (aged 65 years and above) and diabetic patients are at significant risk of being infected with this disease and exhibit the severe form of symptoms which might lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or even death[4]. At the moment, antivirals, antimalarial, immune-based and supportive oxygen therapy are among the off-label use medicines utilized in COVID-19 management. Meanwhile, researchers are actively looking for more potential anti-viral drugs to treat the disease via virtual in silico screening[5].

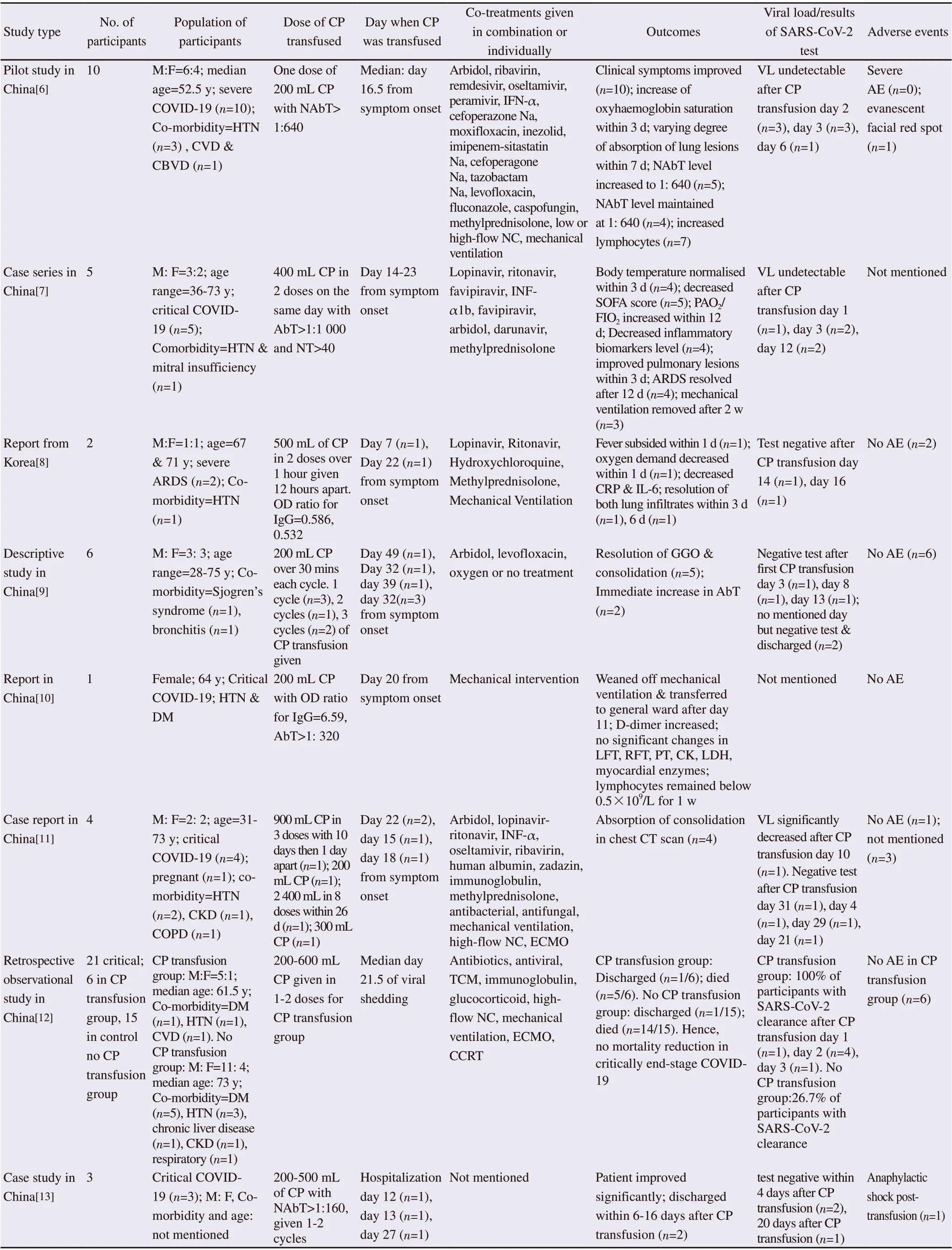

COVID-19 convalescent plasma transfusion has been a topic of interest lately. Convalescent plasma transfusion has been suggested to be used in treating severe and critically-ill COVID-19 patients supported by a rather small number of retrospective cohort study, case series and case reports which is summarized in Table 1.

In fact, convalescent plasma transfusion possess historical usage example as it has been studied and trialed in previous viral diseases outbreak including the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003, H1N1 influenza in 2009, Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome (MERS) and Ebola in 2012[19-23]. Nonetheless, convalescent plasma transfusion has not been approved to be used as a treatment in the mentioned diseases. Given that convalescent plasma transfusion could be a promising potential therapy and serve as the ultimate cure for COVID-19, this review aims to evaluate its possible mechanism of action, pharmacology, benefits and safety as well as its level of usage in current viral outbreak by reviewing literatures on convalescent plasma transfusion.

2. Convalescent plasma

As a form of passive immunization, convalescent plasma is the plasma acquired from individuals that have recovered from an infection. Other than neutralizing antibodies, non-neutralizing antibodies, immunoglobulin G (IgG), immunoglobulin M (IgM), anti-inflammatory cytokines, clotting and/or anti-clotting factors, albumin protein C, protein S and possibly other factors can be found in convalescent plasma via apheresis, collected convalescent plasma is expected to consist sufficiently high antibodies titer against the pathogen of disease which might assist to neutralize the targeted pathogen in recipients upon transfusion, resulting in elimination of the disease and leading to positive clinical outcomes[24]. Furthermore, it was proposed that convalescent plasma may also involve in other antibody-mediated pathways and possibly, immunomodulatory mechanisms[24,25]. As a result, the recipient, especially those who are in severe or critical condition can benefit from the immediate immune response elicited upon convalescent plasma transfusion. The processed product of convalescent plasma, hyperimmune immunoglobulin, is deemed safer as the transfer of potentially detrimental anticoagulation factors found in convalescent plasma can be avoided. Furthermore, it allows production of a standardized preparation with an exact amount of antibody concentration to ensure the effectiveness of the treatment regimen[26]. To produce the highly enriched neutralizing immunoglobulin preparation, complex fractionation processes are involved which makes this therapy not readily available during this emergency[24,27]. Additionally, there is also no complete study assessing the use of hyperimmune immunoglobulin in COVID-19 to date, therefore the use of hyperimmune immunoglobulin could be the focus of future study[28].

2.1. Possible mechanism of action of convalescent plasma transfusion

The possible different mode of actions following convalescent plasma transfusion is discussed below. A brief summary of possible mechanism of actions of convalescent plasma transfusion is shown in Figure 1 for easier understanding.

2.1.1. Direct virus neutralization

The coronavirus has transmembrane spike (S) glycoprotein which forms homotrimers that protrude from the viral surface. In SARSCoV-2, one of the functional subunits of S glycoprotein, the S domain B at the N-terminal region acts as the receptor binding domain and binds to human-angiotensin converting enzyme 2 of the host cell[29,30]. Upon this high affinity binding, fusion between viral and host cell membranes occur for the coronavirus to enter into target host cells which proceeds to viral replication and infection in host[31,32]. Neutralizing antibodies targeting S1 subunits of the S glycoprotein prevent the entry of SAR-CoV-2 into host cell[29,30].

Figure 1. Possible mechanisms of action of convalescent plasma transfusion in COVID-19 patients.

Table 1. Summary of the case series, case reports and retrospective observational studies conducted for transfusion of COVID-19 convalescent plasma (CP) to participants.

Table 1. Continued.

2.1.2. Fc-mediated antibody effector

Constant region of antibody (Fc) interacts with complement proteins and specialized Fc-receptors to mediate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP), and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC). ADCP occurs when phagocytic cells take up virus-antibody or antibodyvirus-infected cells complexes. This leads to antigen processing for presentation on major histocompatibility complex-molecules on cell surfaces or transferred to lysosomes for degradation. Involvement of ADCP in reducing SAR-CoV infection has been shown when anti-SARS-CoV antibodies were given to mouse[33,34]. ADCC is stimulated when there is binding between Fc gamma receptors (FcγR) on natural killer cell to Fc domain of antibodies which are bound to viral proteins on virus-infected cells[35]. Infected cells are killed in result of release of cytotoxic granules. A study by Liu et al. has shown that monoclonal antibodies against Ebola have natural killer cell-predominant ADCC activity[36].

The CDC mechanisms would be activated when C1q binds to Fcbound virus-infected cells, which leads to cascade initiation. As a result, C3 and C5 molecules are released to recruit and activate immune effector cells whereas C3b binds to pathogens and infected cells to undergo immune complex clearance and phagocytosis[35]. Infected cells would then undergo lysis after assembling into membrane attack complex. Nevertheless, complement activation process might lead to pathogenic effect besides its protective effect in an infection[37]. However, a promising recent finding shown in a preprint article of Gao et al., demonstrated that antibody against component C5a able to reduce the lung injury caused by SARSCoV-1 or MERS-CoV N proteins[38].

Although these Fc-mediated antibody effects seem to be beneficial and might lead to positive outcomes of treatment, a balanced amount of antibody must be achieved as antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) effect may happen during convalescent plasma transfusion due to the presence of another form of Fc-mediated antibody (which will be explored later). Currently, there is no established direct link between ADCC, CDC and/or ADCP and ADE in coronavirus infection which was known to occur in dengue virus, thus further studies need to be done on the role of ADE in COVID-19[33,39].

2.1.3. Immunomodulation

Antibodies can also promote maturation and activation of immune cells via divalent antibody fragment F(ab’)2, Fc, dendritic cells, T-cells, B-cells and other immune cells mechanisms[25,40]. It is suggested that convalescent plasma transfusion through intravenous immunoglobulin may neutralize autoantibodies and subsequently reduce the risks of thrombotic event especially in critically ill patients who may have anti-cardiolipin IgA, anti-β2-glycoprotein IgA and IgG antibodies[25,40,41]. FcRn, a receptor which prevents degradation and clearance of IgG when in its saturated form may provide extra immunomodulatory effect by shortening the lifetime of auto-immune antibodies in patients undergoing intravenous immunoglobulin transfusion[25,40]. Sialylated antibodies in IgG activate FcγR to upregulate expression of inhibitory FCγRIIB, leading to reduced inflammatory responses[25,35,40].

In COVID-19 patients with excessive inflammatory stimuli, convalescent plasma transfusion may help to promote antiinflammatory effects elicited by dendritic cells[25]. IgG administration has been shown to reduce maturation of dendritic cells via decreased production of IL-12 and increased levels of IL-10, IL-4 and IL-33. Down regulation of HLA-II and co-stimulated molecules besides IgG-sialylation independent activation of β-catenin may take place to downregulate the inflammation[25]. In a recent study by Bosteels et al., new dendritic cell type was found and named as inflammatory type 2 conventional DC (inf-cDC2), which expresses functional Fc receptors for antibodies found in convalescent plasma[42]. Thus, upon convalescent plasma transfusion, the interaction between antibodies and Fc receptors on inf-cDC2 lead to increased activity of inf-cDC2 to trigger stronger immune response. Severe COVID-19 patients were found to have low levels of CD4+T-cell and CD8+T-cell and high levels of IL-6 and IL-10, which may have benefited from the convalescent plasma transfusion[25,43]. This is because IgG administration is able to balance the levels of CD4+T-cell and CD8+T-cell in addition to facilitation of the Tregs generation. Reduction of Th1 cells, TNFα and IFNγ levels whereas an increment of Th2 cytokines were observed in convalescent plasma transfused-H1N1 patients[19,25,26]. IgG treatment was observed able to regulate cytotoxicity effect on T-cells via modulation of Th17/Treg balance and decreasing levels of CD8+T cells and Th17 cells[25]. Convalescent plasma retrieved from COVID-19 patients were found to contain B-cells, which was shown able to produce monoclonal antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 by inhibiting binding of viral spike protein to ACE2 receptor[44]. Activation of macrophages in COVID-19 patients have been linked to increased cytokine production and pulmonary damage which are regulated by IL-1, IL-6 and JAK[25]. Aside from using these inhibitors to treat COVID-19 patients, IgG administration has been shown to skew macrophages towards antiinflammatory profile[45].

3. Convalescent plasma transfusion in COVID-19 patients

Case series involving the use of convalescent plasma transfusion in COVID-19 patients up to 30th May 2020 and published in English only are summarized in Table 1. Most studies involved severe and/or critically ill patients who are mostly elderly and have co-morbidities. Despite majority of studies showed positive outcomes upon convalescent plasma transfusion, all studies were considered to have risks of bias due to small group of participants, non-randomization and poor participant selection methodology, lack of control group, co-treatment, non-uniform dosage and duration of convalescent plasma transfusion and non-uniform measurement of outcomes. ¬¬

3.1. Detectable antibodies in recovered COVID-19 patients

Patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 induce production of antibodies in their plasma, IgG in particular, which is deemed vital in treating the recipients. The median duration of detectable IgM and IgA antibodies was 5 days post symptoms onset, whereas for IgG, its presence was normally observed 14 days after symptoms onset[46]. However, during the first 7 days of illness, less than 40% of patients were found to have any detectable levels of antibodies. Soon after the 15 day post symptoms, it was found that almost 100% of patients were with detectable levels of IgM and other antibodies[47]. On the other hand, IgG requires at least 19 days starting from the onset of symptoms to be detectable in 100% of patients[48]. Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were detected in patients starting from day 10-15 after symptom onset[49]. Some studies reported that neutralizing antibodies levels were similar across gender and age group; however, older people were found to have significantly higher neutralizing antibody levels[50]. Zeng et al. reported that IgG levels were found to be higher in female severe COVID-19 patients[51]. Higher IgM levels were found in severe and critical COVID-19 patients whereas lower IgG levels were found in critical cases only[52]. In the same study, recovered patients were found to have lower IgM levels compared to deceased COVID-19 patients. Currently, the duration of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies remaining in plasma is unknown, however, more than 90% of recovered patients were found to have the antibodies remaining after 2 years in the 2003 SARS-Co-V outbreak[53]. Enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay is the most commonly used test to detect antibodies. Although samples tested with enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay showed better positivity rate and sensitivity, only limited serological tests are approved for emergency use authorization by the FDA[54]. Some assays measure total antibody concentration, which correlate to neutralizing antibodies whereas some assays measure IgG level. However, there is still uncertainty which type of antibody is effective in the treatment of COVID-19[13,24,55].

3.2. COVID-19 convalescent plasma collection workflow

A workflow of convalescent plasma collection was suggested by Bloch et al., which is in-line with the guidance published by the US FDA[24,56]. Convalescent plasma donors are required to meet the following criteria: (1) confirmed history of positive COVID-19 or positive serological test for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies after recovery; (2) complete resolution of symptoms for at least 14 days before donation; (3) male or non-pregnant female or female with negative HLA antibodies and (4) SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies titers minimum>1: 160 if available. According to the FDA guidelines, the follow-up negative COVID-19 test is not a necessary criterion to be qualified as donor. However, a complete resolution of symptoms for at least 14 days is deemed insufficient as some patients might still have viral shedding after 20 days up to 37 days from illness onset[57]. Thus, donors should be screened for SARS-CoV-2 RNA before proceed for donating processes in order to reduce the risk of transmission via plasma. Convalescent plasma can be collected from eligible donor via fully automated apheresis to optimize yield. About 200-800 mL of convalescent plasma can be collected every 14 days which is an equivalent of two to four therapeutic units from each donor. Convalescent plasma should be stored at 2-6 ℃ as ‘Liquid Plasma’ as it is known that with this storage condition, the collected convalescent plasma is able to last for a duration up to 40 days[13,58]. For long term storage up to 12 months, it should be rapidly frozen below or at -18 ℃ 1) within eight hours of collection, labelled as ‘Fresh Frozen Plasma’ or 2) within 18-24 hours of collection and labelled as ‘Plasma Frozen Within 24 hours’[58]. Convalescent plasma should be collected in uniform containers and appropriately labelled according to the FDA requirements[56]. Collected plasma should be quarantined while pending results from standard blood donor testing for transfusion-transmissible infections, HLA antibodies, nucleic test for SARS-CoV-2 and antibody titer definition[13,24].

3.3. Administration of convalescent plasma

3.3.1. Indications

Currently, the use of COVID-19 convalescent plasma is only regulated as investigational product by the FDA and only accessible to patients via clinical trials. Recently, the FDA allowed alternative access to convalescent plasma through the expanded access program and single patient emergency investigational new drug pathway[56]. In brief, patients have to be COVID-19 positive and suffering from severe or immediately life-threatening event in order to be deemed as eligible for convalescent plasma transfusion. This is also in-line with most of the case series conducted involved only participants who were in severe and/or critical condition. Beneficial outcomes were achieved when convalescent plasma transfusion was given to patients around week two to three after symptom onset and in some cases, after more than four weeks in the conducted case series (Table 1).

3.3.2. Contradictions

Patients who have a history of allergy to human plasma protein products, plasma infusion or sodium citrate are contra-indicated for convalescent plasma transfusion[13,45]. Plasma inactivated with methylene blue virus is not allowed to be used in patients with methylene blue allergy[13,45]. Congenital IgA deficiency (<70 mg/dL in patients who are four years old or older) and patients who have irreversible multiple organ failure at the end stage of critical illness are also contra-indicated for convalescent plasma transfusion[13,45]. Pregnant, breastfeeding, poor compliance, con-current bacterial and/or viral infections and thrombosis are also contra-indicated in the trial settings[13,45].

3.3.3. Dosages

The doses of convalescent plasma transfusion used in the case series are non-standardized. Generally, 5 mL/kg of plasma with titer ≥1: 160 in 200-500 mL was given[13,24]. Bloch suggested that 3.125 mL/kg of plasma should be given for post-exposure as prophylaxis treatment which equivalent to one unit (200 mL) of plasma for transfusion[24]. ABO homogenous plasma is preferred as principle of crossmatching of blood[13,58]. Recommended procedure includes a slow infusion for the first 15 minutes to observe for occurrence of any unfavorable responses as a precaution step of transfusion-related adverse reactions[13].

3.4. Effectiveness of convalescent plasma transfusion

Although almost all of the case series showed positive outcomes in patients upon convalescent plasma transfusion, due to lack of randomized clinical trials or high-quality non-randomized studies, these results (Table 1) are still skeptical as it could be either due to convalescent plasma, other con-current treatments given or underlying natural progression of COVID-19.

3.4.1. Clinical outcomes improvement

Almost all patients improved significantly upon convalescent plasma, showing normalized body temperature, increased PaO2/FiO2, varying degree of absorption of lung lesions, resolved ARDS, mechanical ventilation removed, transferred from intensive care unit to general ward and discharged.

3.4.2. Post-transfusion viral load and results of SARSCoV-2 nucleic test

Not all studies reported the viral load and/or results of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic tests after convalescent plasma transfusion (Table 1). Some patients reported significant reduction in viral load and became undetectable; meanwhile, other patients were tested negative SARSCoV-2 after convalescent plasma transfusion. For the studies which reported discharge rate instead, this can be presumed as patients were tested SARS-CoV-2 negative twice as it is one of the discharge criteria[59].

3.4.3. Survival and mortality rate

Fortunately, almost all of the patients survived except in three studies reported by Ramachandruni, Huang and Zeng with unstated cause of death patient cases[12,15,18]. The high survival rate could be contributed by convalescent plasma transfusion and/or concomitant treatments given like antibiotics, antivirals and antimalarial. It is recommended to give convalescent plasma transfusion to potential critically ill COVID-19 at early stage of disease as it was found that convalescent plasma transfusion may be unable to avert poor outcome and reduce mortality rate in end-stage COVID-19 patients[12].

3.5. Safety of convalescent plasma transfusion

Generally, convalescent plasma transfusion was well-tolerated in almost all participants of the case series listed in as Table 1. Nonetheless, evanescent facial red spot, anaphylactic shock, fever, morbilliform rash and deep-veined thrombosis were reported as one case each. In a recent observational study of 5 000 patients receiving COVID-19 convalescent plasma transfusion, the incidence of serious adverse events was <1% in which two out of the 36 cases were judged as definitely related to convalescent plasma transfusion[60]. The seven-day incidence of mortality was 14.9%[60]. It is shown that convalescent plasma transfusion is safe in hospitalized COVID-19 patients although there might be some risks of adverse events as explained below.

3.5.1. Antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) and antibody-enhanced immunopathology

ADE occurs when (1) non-neutralizing or sub-neutralizing antibody-bound virus binds to activating FcγR on immune cells leading to Fc receptor-mediated endocytosis or phagocytosis and (2) antiviral activities are inhibited due to co-ligation of inhibitory receptors leading to increased viral replication[39,61]. Antibodyenhanced immunopathology takes place when antibody activates ADCC or complement pathway. Ultimately, both bring about modulation of immune response, enhanced inflammation thus causing patents’ clinical condition to deteriorate upon convalescent plasma transfusion with unknown specific signs and symptoms of ADE in coronavirus infections in humans. This was observed in dengue virus when antibodies were developed during prior infection leads to clinical severity when re-infected with different viral serotype[62]. In SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, only in-vitro studies have been associated with ADE when low concentration anti-sera or monoclonal antibodies were given[61,63,64]. Currently, no invivo clinical nor epidemiological evidence is available to prove the association between ADE and coronavirus infections, and no report of severe cases of re-infection of coronavirus[24,39,60]. On top of that, SARS-CoV-2 preferentially infects human-angiotensin converting enzyme 2-expressing epithelial cells and neutralizing antibodies producing cells rather than targeting Fc-expressing immune cells. High concentration of polyclonal antibodies found in convalescent plasma and the lack of in-vivo studies suggest unlikely relevance between ADE and convalescent plasma transfusion. Despite that, precautions are still advised especially when convalescent plasma transfusion is given to high-risk patients by monitoring for any deterioration of clinical condition of patients.

3.5.2. Transfusion-associated acute lung injury (TRALI) and transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO)

TACO and TRALI are the most common causes of transfusionrelated mortality in critically ill patients. TACO is presented as circulatory overload, leading to pulmonary edema and left arterial hypertension, whereas TRALI is manifested as bilateral pulmonary edema with minimal or no circulatory overload. There are two categories of TRIALI: type 1 for patients without ARDS risk factors and type 2 for patients with ARDS risk factors. The underlying lung injury associated to COVID-19 disease progression made it difficult to differentiate the diagnosis between TACO and TRALI and determine whether reported mortality was due to underlying disease progression or adverse events of TACO and/or TRALI. In critical-ill patients, the rate of TACO and TRALI are expected to be around 10%, however, current data showed an overall rate of <1% of transfusion-related serious adverse events[60]. In addition to the low rates of TRALI and TACO, routine donor screening for HLA antibodies in pregnant women and preferential male convalescent plasma donors can help to reduce the risk of TRALI, thus reassuring the use of convalescent plasma transfusion[13,24,60].

3.5.3. Allergic transfusion reactions and coagulation derangements

As reported by some case series (Table 1), some recipients experienced adverse reactions like fever, rashes and anaphylactic shock post transfusion, which could be due to allergic reaction. Fever and rashes are considered tolerable and can resolve spontaneously by symptomatic treatment or by decreasing transfusion rate. Although considered life-threatening, the incidence of anaphylactic shock and serious adverse events are rare (one in every 500 patients) and were observed in severe patients only[60,65]. The contraindication of convalescent plasma transfusion to patients with history of allergy with blood plasma products should be followed to further reduce the risk of allergy transfusion risk. Convalescent plasma transfusion may also theoretically exacerbate coagulation derangements linked to severe COVID-19[60]. However, current observation study reported that no severe thrombotic events within four hours of serious adverse events was observed. Hence, convalescent plasma transfusion was shown not to acutely exacerbate underlying disordered coagulation among critically ill COVID-19 patients. Regardless, patient should be monitored and slowly transfused for the first fifteen minutes to watch out for any serious adverse events[13].

3.5.4. Transmission of infectious pathogen

This is a theoretical risk as currently there are no reports of transmission of respiratory virus via blood transfusion despite no screening for common respiratory virus like influenza is implemented[24]. For SARS-CoV-2, the recipient is already infected and not considered as transfusion-transmitted infusion. In addition, the donated convalescent plasma will be tested for SARSCoV-2 nucleic test before transfusing into recipient[13]. The risk of transmission of hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus and HIV via convalescent plasma transfusion can be reduced by screening for their antigens and/or antibodies after collection before transfusing into recipient[13].

3.6. Clinical evidences on the use of convalescent plasma transfusion for COVID-19

Table 1 summarizes the conducted case series and observational studies. Although the reported outcomes of the use of convalescent plasma transfusion may seem promising, these studies design portrayed very high risk of bias such as small study sample size, short-term follow-up and lack of adjustment for potential confounders. The US FDA has approved the use of convalescent plasma as investigational new drug for critically ill COVID-19 patients provided that approval from the FDA is obtained[56]. To study the use of convalescent plasma in COVID-19, doctors are required to submit investigational new drug application. Numerous clinical trials are underway to further evaluate the use of convalescent plasma as discussed by Valk et al[28].

4. Conclusions

It has been challenging in battling this new decade’s global health crisis without availability of a definitive management and therapy. As per discussed, convalescent plasma is currently an investigational product for the treatment of COVID-19. The convalescent plasma derived from COVID-19 recovered patient may contain antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and may potentially provide protection against infection. However, its safety and efficacy use in COVID-19 patients have yet to be established completely. The risks and benefits information discussed above suggested that convalescent plasma is a promising state-of-art therapy for COVID-19 patients. Furthermore, the ongoing clinical trials in order to evaluate the efficacy, safety, optimal dose, duration and timing of administration may provide the potential solution in overcoming this pandemic.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The project is financially supported by Taylor’s University Emerging Grant (TRGS/ERFS/2/2018/SBS/016), Monash Global Asia in the 21st Century (GA21) research grants (GA-HW-19-L01 & GA-HW-19-S02), and Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2019/WAB09/MUSM/02/1 & FRGS/1/2019/SKK08/TAYLOR/02/2).

Authors’ contributions

The literature searches and data collection were performed by S.N and STN. The manuscript was written by S.N., and S.T.N. The manuscript was critically reviewed and edited by K.B.L., Y.C.L., L.C.M, G.B.H, Y.W.H and T.Y.Q. The project was conceptualized by G.B.H.

杂志排行

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- ARIMA models forecasting the SARS-COV-2 in the Islamic Republic of Iran

- Genetic variation and phylogenetic relationship of Hypoderaeum conoideum (Bloch, 1782) Dietz, 1909 (Trematoda: Echinostomatidae) inferred from nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequences

- Effect of climate change on spatial distribution of scorpions of significant public health importance in Iran

- Phytochemical profiling and biological activity of Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour.) mediated by various solvent extracts against Aedes aegypti larvae and toxicity evaluation

- Clinical outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis C after generic direct-acting antiviral treatments in Vietnam: A retrospective analysis