Hypertension and diabetes synergistically strengthen the association with cataracts

2020-10-09JinJinLi1MoDongLi1JieLi1XiaoYang1DanXia1YuLi1WeiWang2FeiYan2JianZhang

Jin-Jin Li1, Mo-Dong Li1, Jie Li1, Xiao Yang1, Dan Xia1, Yu Li1, Wei Wang2, Fei Yan2, Jian Zhang

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

A ge-related cataract (ARC) is the leading cause of visual impairment worldwide, andresponsible for over 50% of blindness in China[1-2]. The major driving force behind the development of ARCs is the natural aging process. At present, surgery is the only effective treatment for cataracts but remains expensive in the developing world[3]. Fortunately, studies show that cataracts often develop at different rates, and may stop progressing in its early stages and vision is impaired only slightly if appropriate measures are taken[3]. Therefore, it is vastly critical to explore effective primary prevention strategies that may modify the risk factors and slow or halt the progress of ARCs.

Cardio-metabolic diseases, including hypertension and diabetes, have been observed to be associated with various ocular diseases although the epidemiological evidence on eye diseases other than diabetic retinopathy remains inconclusive. It is worthy of note that the majority of previous studies were conducted among Western populations, limiting the generalizability of the conclusions to Chinese and other Asian populations. On the other hand, driven by rapid increases in the number of older people and the increasing popularity of a sedentary life-style, both hypertension and diabetes have reached an epidemic level in China and other Asian countries[4], and the comorbidity of two conditions occurs more frequently among Asians than in other populations[5], exacerbating the prognosis of each condition, and complicating the diagnoses and treatment of other medical diseases. However, to the best of our knowledge, no efforts have been made to assess how hypertension and diabetes synergically strengthen the association with cataracts among Chinese. With a hospital-based group-matched case-control study, we aimed to assess the association between hypertension, diabetes and cataracts, in particular, the association between cataracts and comorbid hypertension and diabetes.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

StudyPopulationWe retrospectively reviewed the administrative records of 6,467 patients who were 50 years or older, and hospitalized from January 1st, 2011 to May 20th, 2017 to the department of ophthalmology, People’s Hospital of Fuyang, Anhui Province, China. All diagnoses were based on discharge rather admitting diagnoses. Tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed. Due to the nature of secondary data analyses, written informed consents were not collected from the patients, the current study was exempt from ethics review by the IRB committees from author’ institutes respectively.

AssessmentofCataractsCataracts were diagnosed for treatment purposes with the consideration of structural and functional evidences, and clinical complains. The years of poor vision, and corrected vision worse than 0.3 were considered the primary indicators of a cataract. Lens opacity was assessed from retroillumination lens photographs and digital slit-lamp photographs (SL 980N, CSO, Italy, SL-1E and SL-2G, TOPCON, Japan) after dilating pupils. An ARC was defined as the presence, in at least one eye, of cataract or evidence of previous cataract without the history of trauma, the surgical history of other eye problems, ocular exposure to radiation, or using specific medications such as corticosteroids, the presence of congenital anomalies, inflammation, or tumor. Visual acuity in each eye was measured using a standard visual acuity chart, with distance spectacles if worn. No efforts were made to further classify cataracts into subtypes, such as nuclear, cortical or posterior subcapsular cataracts in the current analysis. In total, 4,415 cases with any type of cataracts were identified. After the exclusion of 99 cases with a dual diagnosis of cataract and ocular trauma, 4,316 cases of non-traumatic cataracts were retained for the current analyses, including 3,343 ARCs.

RecruitmentoftheCataract-freeControlsWith the assumption that an injury may occur randomly, we selected the ophthalmological patients aged 50 years or older hospitalized for traumatic eye diseases as random samples from the general population, and designed these traumatic patients as group-matched controls. In total, 478 cases of ocular traumas were recruited, among them, 99 patients (21% of trauma cases recruited for current study) seeking inpatient care with traumatic cataracts were excluded to ensure that the controls were cataract-free. Consequently, 379 cataract-free trauma controls were included for the current analyses.

DiagnosesofHypertensionandDiabetesAn ophthalmological patient was considered to have diabetes if any of the following criteria were met: 1) self-reported previous physician-made diagnosis of diabetes and treatment with antidiabetic medications or diets; 2) glycated hemoglobin (A1c) level ≥7.0%; 3) random blood glucose ≥ 200 mg/100 mL (to convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0555), or (d) fasting blood glucose ≥ 126 mg/100 mL. We combined type I and type II diabetes since there were too few cases of type I diabetes for drawing meaningful conclusions separately from type II diabetes. A patient was considered to be hypertensive if systolic blood pressure was consistently ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg anytime during the hospital stays, or the patient used antihypertensive medications. Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were periodically measured with an automated sphygmomanometer during the hospital stays.

AssessmentofCovariatesAfter the age of 50 years old, the relationship between the aging-related eye diseases and diabetes among Chinese Singaporeans turned to be linear, therefore, we modelled age as a continuous variable. To simplify the study and remedy the missing data on the health care accessibility, we roughly grouped the study participants as from rural or urban, and used urbanity to control for the financial and physical accessibility. All patients living in cities,regardless of their actual types of residence (permanent or not), were categorized as urban residents, otherwise as rural.

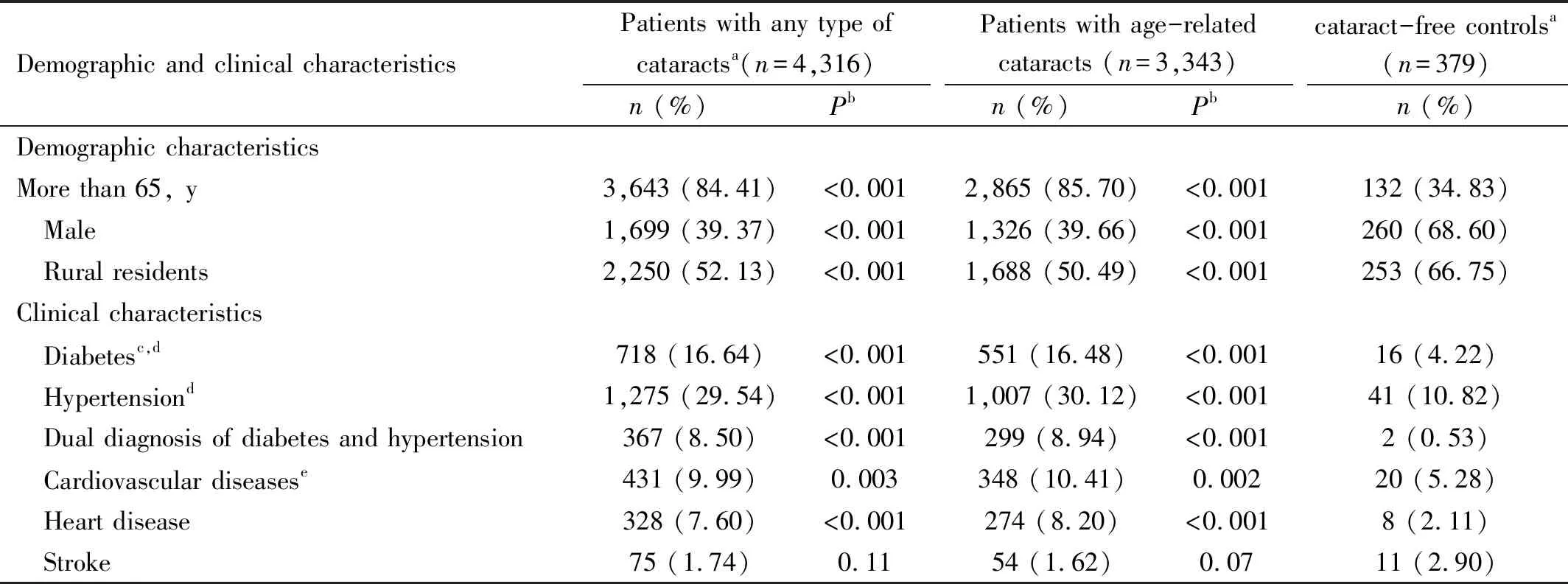

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of cataract cases and cataract-free controls, adults aged 50 years and older, People’s Hospital of Fuyang, China(2011-2017)

StatisticalAnalysisThe statistical analyses were performed using SAS (9.6, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA). The existing literature and clinical observations confirmed that trauma patients were usually younger than the patients with cataracts, and men were at a higher risk of ocular trauma but a lower risk of cataracts compared to women[6-10], the prevalence difference of cardio-metabolic diseases between cataract cases and cataract-free traumatic controls may be attributed towards age and sex difference between cases and controls. To control for the different distributions of age, sex, and health care accessibility between cases of cataracts and cataract-free controls, we ran unconditional logistic regressions to obtain odds ratios (ORs) of hypertension, diabetes, and comorbid hypertension and diabetes with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) adjusted for age, sex and health care accessibility, and to determine whether the odds of hypertension and diabetes among patients with cataracts differed from that among cataract-free controls. To assess the synergistic interaction between hypertension and diabetes on the association with cataracts, we included an indicator in the right side of the regression equations to classify patients into four groups: 1) hypertensive patients; 2) diabetic patients; 3) patients with both; 4) patients with neither (reference). We conducted separate analyses to compare cataract-free patients to the patients with any type of cataracts other than traumatic cataracts, and to compare cataract-free patients to patients with ARCs. As the last step, we used the coefficient of determination,i.e.r2, of regressions to assess how close the data fitted the regression lines, and estimate the contributions from each variable selected in current study on the variability of odds of cataracts. Two-sidedP-value less than 0.05 was considered as an indicator of statistical significance.

RESULTS

Significant differences were observed between cataract cases and cataract-free controls in both demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1). More than 80% of cataract cases (84.41% of cases with any type of cataracts and 85.70% of ARCs) in contrast to 34.83% of cataract-free controls were 65 years or older, 39.37% of patients with any type of cataracts while 68.60% of cataract-free controls were men. Stroke was the only selected cardio-metabolic diseases, for which the difference between cases and control failed to reach statistical significance, 1.74% of patients with cataracts and 2.90% of cataract-free controls reported a history of stoke. The prevalence of diabetes in patients with any type of cataracts was four times higher than that among cataract-free controls, 16.64%vs4.22%. The prevalence of hypertension was more than doubled in cataract patients than in cataract-free controls, 29.53%vs10.82%. Lower than 1% of cataract-free controls but 8.50% of cataract patients were with a dual diagnosis of diabetes and hypertension.

After controlling for age and sex differences with multivariable regressions (Table 2), hypertension was weakly [OR=1.75 (95%CI=1.19, 2.58)], and diabetes was strongly [OR=3.38 (1.86, 6.15)] associated with cataracts. TheORof comorbid hypertension and diabetes was as high as 17.20 (4.19, 70.67) among patients with any type of cataracts, and 18.20 (4.38, 75.59) among patients with an ARC. Not surprising, one year increase of age was associated with a 16% increased odds of an ARC [OR=1.16 (1.15, 1.18)], and an ARC was associated with a quadrupled odds of being a woman [OR=3.62 (2.78, 4.70)]. Overall, a cataract was not significantly associated with heart diseases and strokes after controlling for diabetes and hypertensions. The associations between cataracts and the risk factors selected in current study did not differ between ARCs and all cataracts combined.

Table 2 The adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) of risk factors among cataract cases compared to cataract-free controls, adults aged 50 years and older, People’s Hospital of Fuyang, China, 2011-2017a

Table 3 Marginal contributions from selected factors to the odds variations of aging-related cataracts among adults aged 50 year, People’s Hospital of Fuyang, China, 2011-2017

More than 30% of the odds variations of cataracts was explained by age, and about 5% was explained by gender (Table 3). After adjustment for age and sex, roughly 3% of the odds of cataracts were attributable to diabetes, followed by the calendar year of hospitalization, hypertension, the types of residential area, and other cardiovascular diseases other than hypertension. In total, the factors examined by the current analyses explained more than 40% of the odds variations of cataracts in the study samples.

DISCUSSION

Among Chinese aged 50 years and older, we reported a weak association between hypertension and cataracts, a strong one between diabetes and cataracts, and a stronger one between cataracts with comorbid hypertension and diabetes.With few exceptions, previous studies observed that diabetes was associated with cataracts among westerns[6-17]and Sino-Mongolians[18-23], weakly (odds or risk ratio: 1-2)[6,9-13,17-19,21-22], moderately (odds or risk ratio: 2-3)[7-8,14-15,20,23]or strongly (odds or risk ratio: 3 and above)[16], in the developing world[22-23]and the developed countries[6-21,24], from case-control[6], cross-sectional[9-10]and cohort studies as well[11-16]. To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first examining the relationship between diabetes and cataracts among Chinese living in the mainland of China. We found that diabetes was associated with cataracts in a relatively stronger manner (OR=3+) among Chinese than among other populations[6-15,18-23].

In contrast to the strong association between diabetes and cataracts, the association between hypertension and cataracts was found to be relatively weak and less consistent in the existing literature. Some found that the history of hypertension[18,21], the presence of hypertension[6,8,13-14,20,22-23,25], or taking anti-hypertensive medication[11-12,19,26]were associated with an elevated risk or odds of cataracts[6,8,11-14,18-19,21-23], cataract surgeries[26], or lens opacities[25]. A non-significant association between hypertension and cataracts was also reported[27]. Surprisingly, an inverse relationship was also observed, revealing that a decreased rather than an increased risk of cataract surgery[7], and lower prevalence of cataracts[28]were associated with hypertension. It is noteworthy that, the Beijing Eye Study, a population-based study conducted decades ago among Chinese, did not find an association between hypertension and cataracts[27]. The cataract cases in the current study, a typical hospital-based one, were generally at an advanced stage compared to those in the Beijing Eye Study. Misclassification was less likely in a hospital-based analysis relatively to a population-based one[14], which may explain parts of the discrepancy of the conclusions between Beijing Eye Study and the current observation.

Hypertension and diabetes are the most common components of cardio-metabolic syndromes, and there is a substantial comorbidity between these two conditions[5,13-14]. Studies in Caucasians[13], and Malay adults[20]found that the two conditions acted synergistically to increase the risk of cataracts. During an 8-year follow-up of the Swedish women, the risk of incident surgical extraction of cataracts increased by 43% in women with diabetes, 12% in women with hypertension, and 68% in women with a dual diagnosis[13]. In the Singapore Malay Eye Study, theORof cataracts was 1.89 (95%CI=1.42, 2.40) for patients with diabetes, and 1.92 (95%CI=1.47, 2.52) for patients with hypertension. A dual diagnosis of hypertension and diabetes was associated with an almost 5 times higher odds of cataracts [OR=4.73 (95%CI=2.16, 10.34)][20]. The current study observed an even stronger multiplicative interaction. Similarly, the differences in study populations may explain the discrepancy of the associations estimated in Singapore Malay Eye Study and the current analyses.

Another innovative effort of the current study was to quantify the contributions of various factors to the occurrences of cataracts. Studies found that the associations between cardio-metabolic diseases and cataracts or cataract extraction were stronger at a younger age, and were getting weaker among the elderly[6]. No associations between hypertension, diabetes and cataracts were reported among elderly populations[21], and the authors attributed the age-modifying effects to the increasing influence of other factors that wash out the effect of cardio-metabolic diseases[29]. Current analysis suggested that, instead of competitive risk factors, non-significant association among elderly may be explained by the ceiling effect from age. The marginal impacts from cardio-metabolic diseases diminished quickly when most patients at advanced age presented an ARC. It is critical to stratify the analyses by the age of study populations for future systematic reviews or meta-analyses in assessing the relationship between cardio-metabolic diseases and cataracts.

StudyLimitationsThe current study is subjected to limitations. There were significant differences between cataracts and non-cataract trauma controls in age distribution. The confounding from age, if not fully removed by a group-matching design, should impact the association between cataracts and hypertension, cataracts and diabetes equally since both hypertension and diabetes are strongly and significantly associated with age[13-14]. However, a weak association was found between hypertension and cataracts and a strong association was found between diabetes and cataracts in current analysis, indicating that the residual confounding from age might be not a concern, the associations detected by current analysis were independent from age distribution. Different types of cataracts might be associated with different sets of risks[9,12,22,25,30-32]; different types of hypertension[22,33], and different types of diabetes[11-12,16,22]may associate with cataracts in different manners. However, we failed to examine the associations by the types of cataracts, hypertension, and diabetes due to data availability. The duration of hypertension and diabetes was not available. Cataracts and cardio-metabolic diseases may share sets of risk factors rather than causally correlate[6], the cross-sectional nature of the study precluded us from making causal inferences. As a hospital-based study, we drawn the controls from the same source as the cases, presumably from the same segments of the populations. Therefore, cases and controls were group-matched on social, economic, ethnic, and environmental factors. It also led to biases when the risk profiles of the controls differ from that in general population, clouding the external generalizability of the current analyses. In spite the fact that 21% of traumas were excluded due to possible traumatic cataracts, a substantial percentage of cataracts are undetected at a population level, we may have failed to exclude all traumas resulted from poor vision due to undiagnosed cataracts, compromising the statistical power and leading toward a null association rather a spurious one. The ophthalmic diagnoses were made exclusively for a treatment purpose, referral or diagnostic biases may exist. Finally, cigarette smoking, excessive body weight, dyslipidemia and other cardio-metabolic risk factors have been shown to be associated with cataracts[34], however, we failed to include these potential confounders.

PolicyImplicationandClinicalRelevanceThe cataract surgical rate (CSR) in Anhui province of China, where the current study was conducted, was as low as 600 per million[35], a small fraction of the CSR in the developed world[36]. The recent survey found that two thirds of those with bilateral visual impairment or blindness because of cataracts remained in need of sight-restoring surgery[37]. As the population is aging quickly, the backlog of urgent cataract cases, which require surgical interventions, will be further expanded. More urgently, the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes are increasing unprecedentedly in China, and the comorbidity between hypertension and diabetes is highly prevalent among Chinese and other Asians compared to Western populations[5]. If the strong synergistic relationship between cataracts and comorbid hypertension and diabetes is confirmed to be causal, the escalating epidemics of hypertension and diabetes in China and other parts of Asia will have a great impact on the incidence of cataracts, generating additional challenges on the top of debt bomb of aging population. Integrated national strategies to address the epidemic of cardio-metabolic diseases and vision impairment are urgently needed. In clinical practice, yearly screenings for diabetic retinopathy offers a great opportunity to early identify a cataract, and design appropriate treatment plan to prevent interfere with patients’ performance of normal daily activities. Current study also suggests that mitigating the aggravating impact on cataract from comorbid cardio-metabolic conditions should be exercised in early stage as aging dominates the development of cataract in the late stage of cataracts, and the likelihood to slow or halt the progress of ARCs diminishes exponentially with age.