Inhibition of Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP) by Ko143 Can Affect Pharmacokinetics of Enrofloxacin in Exopalaemon carinicauda

2020-09-27ZHAIQianqianXUYangLICuipingFENGYanyanCUIYantingMALiandLIJian

ZHAI Qianqian, XU Yang, LI Cuiping, FENG Yanyan, CUI Yanting, MA Li, and LI Jian

Inhibition of Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP) by Ko143 Can Affect Pharmacokinetics of Enrofloxacin in

ZHAI Qianqian1), 2), *, XU Yang1), 2), LI Cuiping1), 2), FENG Yanyan1), 2), CUI Yanting1), 2), MA Li1), 2), and LI Jian1), 2), *

1),,,,266071,2),,266237,

Adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporter breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) exists highly in the apical membranes of epithelia, and is involved in drug availability. Ko143 is a typical inhibitor of BCRP in rodents. The synthetic antibacterial agent enrofloxacin (ENRO) is a fluoroquinolone employed as veterinary and aquatic medicine, and also a substrate for BCRP.gene highly expressed in the hepatopancreas and intestine ofas was determined with real-time quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) method. The effects of Ko143 on the abundance ofmRNA and ENRO pharmacokinetics inwere studied. The mRNA abundance ofdecreased significantly in he- patopancreas and intestine (<0.05) after Ko143 treatment. Co-administration of Ko143 significantly changed the pharmacokinetics of orally administered enrofloxacin, which was supported by higher distribution half-life (1/2α), elimination half-life (1/2β), area under the curve up to the last measurable concentration (AUC0-t), peak concentration (max) and lower clearance (CL/). These findings revealed that Ko143 downregulatesexpression in hepatopancreas and intestine, thus affects the pharmacokinetics of orally administered enrofloxacin in. The drug-drug interaction can be caused by the change in BCRP activity if ENRO is used in combination with other drugs in shrimp.

BCRP;; pharmacokinetics; enrofloxacin; Ko143

1 Introduction

Adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette (ABC) transpor- ter breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP), also known as ‘, is an efflux transporter with the specificity for a broad range of substrates. BCRP locates in various types of tumour cells, normal tissues (., brain, placenta, small intestine, liver, testis, ovary, prostate gland) and the apical membranes of breast ducts/lobules (Maliepaard., 2001; Jonker., 2005). In mammals, BCRP plays a key role in the modulation of pharmacokinetics and bio- availability of agents (Sooud, 2003; Daood., 2008; Hua., 2012). Drug disposition can be altered by changing BCRP activity (Kruijtzer., 2002; Eriksson., 2006). BCRP activity can be down-regulated and induced by die- tary compounds, hormones and xenobiotics (Bertilsson., 1998; Staudinger., 2001).

BCRP content in the organs of aquatic animals has been documented (Zhou., 2009; Chang., 2012; Zhai., 2017). Some drugs used commonly in aquaculture and animal husbandry, for example, nitrofurantoin, erythro- mycin and fluoroquinolones, are substrates of BCRP in mammals (Ando., 2007; Wright., 2011; Ballent., 2012). However, whether the change inexpression affects drug disposition in aquatic animals, especially in prawns, is not known. The role of BCRP transporters in drug disposition in aquatic animals needs to be investigated.

Ridgetail white prawn () inhabits on the coasts of Yellow Sea and Bohai Sea, China. It contributes to one-third of the gross output of polyculture ponds in eastern China (Duan., 2013).can reproduce in large numbers, grows rapidly, adapts to a wide range of environments, and is of moderate size suitable for experimental operation and laboratory culture, making it a good crustacean for experimentation (Li., 2012; Wang., 2013; Duan., 2014). The BCRP transporter exists widely in various tissues and organs of, and its gene expresses highly in hepatopancreas and intestine (Zhai., 2017).

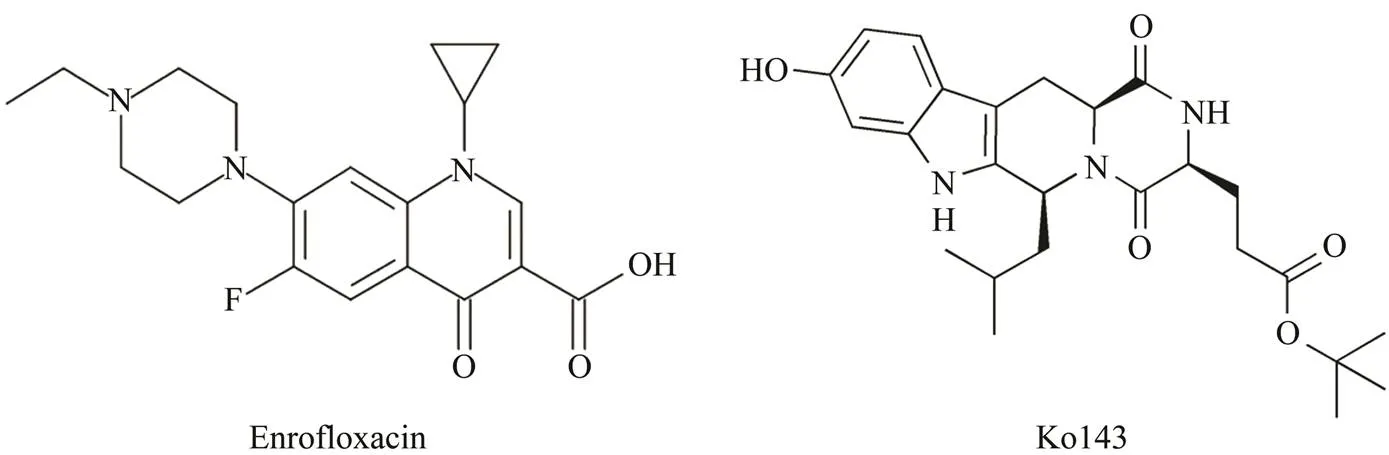

The synthetic antibacterial agent enrofloxacin (ENRO) (Fig.1) is a fluoroquinolone employed as veterinary and aquatic medicine. It is also a substrate of BCRP (Real.,2011). The compound Ko143 [(3S,6S,12S)-1,2,3,4,6,7,12, 12-octahydro-9-methoxy-6-(2-methylpropyl)-1,4-dioxopyrazino [1’,2’:1,6] pyrido [3,4-] indole-3- propanoic acid 1,1-dimethylethyl ester] is a potentinhibitor and a candidate for PET imaging studies along with a suitable radiotracer. Derived from fumitremorgin C (FTC) as a non- toxic analog, Ko143 (Fig.1) has been used over the past decade to examine the interaction betweenand phar- maceutical drugsand(Allen., 2002; Matsson., 2009). Here in this study, we determined the effect of Ko143 on the expression ofin the tis- sues of. The effect of Ko143 on ENRO pharmacokinetics in different tissues was also determined to better understand the function ofBCRP transporter in fluoroquinolone disposition in.

Fig.1 The chemical structure of ENRO and Ko143.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Drugs and Medicated Feed

The ENRO (purity>98%) used in preparation of the medicated feed was purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China). Ko143 (purity>99%) was obtained from Sigma- Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA). The medicated feed was administered at 2% of total body weight (BW), and was made by top-coating the drug powder uniformly on the pellet feed using egg white.The ENRO-medicated feeds weremade with 10, 20 and 40mgENRO per kg BW, respectively. The Ko143 andENRO-medicated feeds were made with 5mgKo143 per kg BW and10, 20 and 40mgENRO per kg BW, respectively.

2.2 Shrimp and Culture Condition

(length: 4.59cm±0.45cm; weight: 1.32g±0.21g) were purchased from a commercial farm (Qingdao, China) and cultured in sea water (salinity 30, pH 8.0±0.2) at 23℃±1℃ for 7 days before processing. Two-thirds of the water in each shrimp group was renewed once a day. The collection and handling of the animals in this study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, and all experimen- tal animal protocols were written and used following the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals of Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences.

2.3 Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Thirty-six healthy adultwere divided into a control group (=18) and a Ko143-treated group (single oral administration of 5mgkg−1BW each) (=18). Two hours after Ko143 treatment, the gills, hae- mocytes, heart, muscles, hepatopancreas, eyestalks, intestines, stomach and ovaries were sampled. Three shrimps were randomly selectedas one sample from each group, and there were six biological replicates for each tissue in each group.

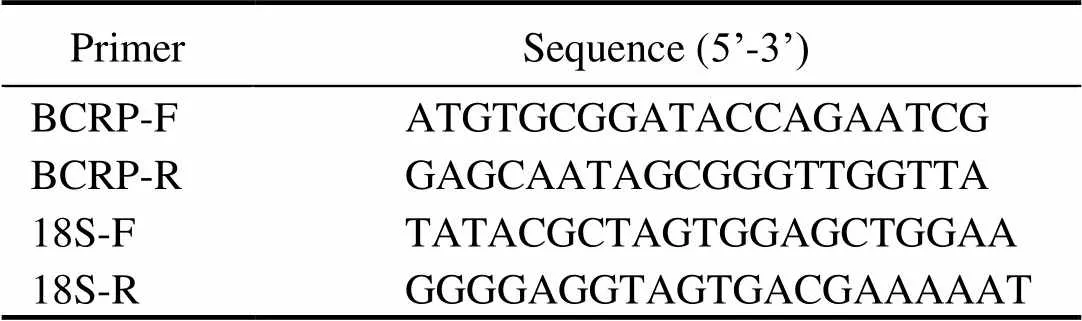

Total RNA was isolated from tissues using TRIzol™ Rea- gent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After digestion of genomic DNA (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA), the mRNAs were reversely transcribed with M-MLV reverse trans- criptase (Promega). Then, quantitative PCR (q-PCR) was undertaken on an ABI PRISM 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using SYBR®Premix Ex Taq™II (TaKaRa Bio, Dalian, Chi-na) and primers listed in Table 1. PCR condition was 95℃ for 30s first, then 40 cycles of 95℃ for 5s and 60℃ for 34s, followed by one additional cycle of 95℃ for 15s, 60℃ for 1min and 95℃ for 15s. The18S rRNA (GenBankaccession number: GQ369794) ofwas usedas the internal control. Fold-change in relative gene expression to control was determined with standard 2−ΔΔCtmethod as we did early (Zhai., 2017).

Table 1 Primers used in this study

2.4 Pharmacokinetic Anaysis

Healthy adult(=1620) were divided into six treatment groups, 270 individuals in a tank each group. The first three groups received medicated feed at a single oral dose of 10, 20 and 40mg ENRO per kg BW, respectively. The remaining three groups were given medicated feed at a single oral dose of 5mg Ko143 per kg BW and 10, 20 and 40mg ENRO per kg BW, respectively. Blood, hepatopancreas, intestines and muscles were collected at 0.083, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96, 120 and 144h after drug administration. Then 200μL of hemolymph each individual was drawn directly from the cardiocoelom using sterile syringes containing 200μL of anti-coagulant solution (1.588g of sodium citrate, 3.92g of sodium chloride, 4.56g of glucose, 0.66g of EDTA-2Na,200mL of ddH2O). Shrimps from six groups were dissect- ed carefully and the hepatopancreas, intestines and muscles were collected immediately.Eighteen shrimps were selected randomly at each time point each group. Three shrimps were combined to use as one sample to be analyzed. Thus, there were six biological replicates each tissue each group each time point.The ENRO level in blood and tissues was analysed using high-performance liquid chromatography as was described by Liang(2014)with a modification (0.017molL−1phosphate-triethyla- mine buffer: acetonitrile, 85:15, v/v as the mobile phase).Calculations of pharmacokinetic parameters were undertaken with Drug and Statistics v2.0 (Center for Clinical Drug Evaluation, Wannan Medical College, Wuhu, China) using the compartmental model.

2.5 Data Analysis

All data were presented as mean±SD. Statistical ana- lysis was performed using SPSS v17.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The mRNA abundance data in different tissues and pharmacokinetic parameters of enrofloxacin in plasma, hepatopancreas, intestines and muscles were ana- lyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by the Student’s- test to find any significant difference between ENRO and Ko143+ENRO treatments.

3 Results

3.1 Effect of Ko143 on Abundance of BCRP Gene mRNA in E. carinicauda

Before treatments, the highest expression level ofgenewas in hepatopancreas, followed by that in intestine (Fig.2). The mRNA abundance in stomach, gills, muscles, eyestalks and heart were low, and virtually no expression of the gene was found in haemocytes and ovaries.gene expression was also recorded in different tissues after Ko143 treatment. Compared with the control, the expressions ofwas downregulated significantly in hepatopancreas and intestines (<0.01) after Ko143 treatment.The mRNA level in other tissues did not show significant differences (>0.05).

Fig.2 Expression of BCRP gene in E. carinicauda with and without Ko143. Expression of BCRP gene was detected by real-time RT PCR. 18S rRNA was used as the reference for normalization (n=6). ∗∗(P<0.01) and ∗(P<0.05) show the significant difference between control and Ko143-treated E. carinicauda.

3.2 Method Validation for ENRO Detection

The limit of quantitation (LOQ) and limit of detection (LOD) of ENRO were 0.05 and 0.02μgmL−1, respectively. After detection of ENRO at 3 concentrations (0.05, 1, and 10μgmL−1. The recovery rate of ENRO at 3 concentrations was all higher than 85%. The stability test revealed that the precision of ENRO was less than 12% under four conditions: short-term placement (4h) at room temperature 25℃; freezing and thawing three times; long-term (2 weeks) freezing (−20℃); and placement for 13h at room temperature 25℃before injection, which complied with the test requirement for biologic samples. The correlation coefficient for the calibration curves was 0.9996.

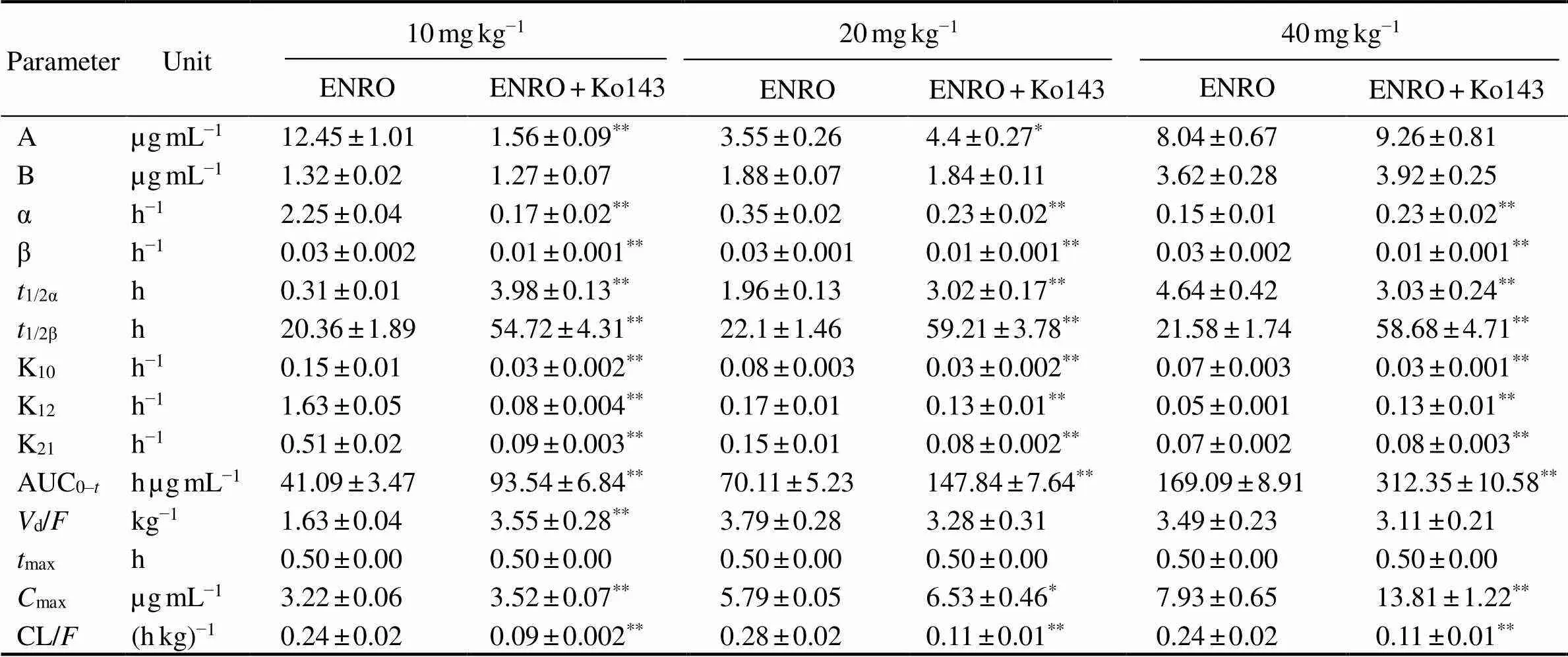

3.3 Effect of Ko143 on ENRO Pharmacokinetics

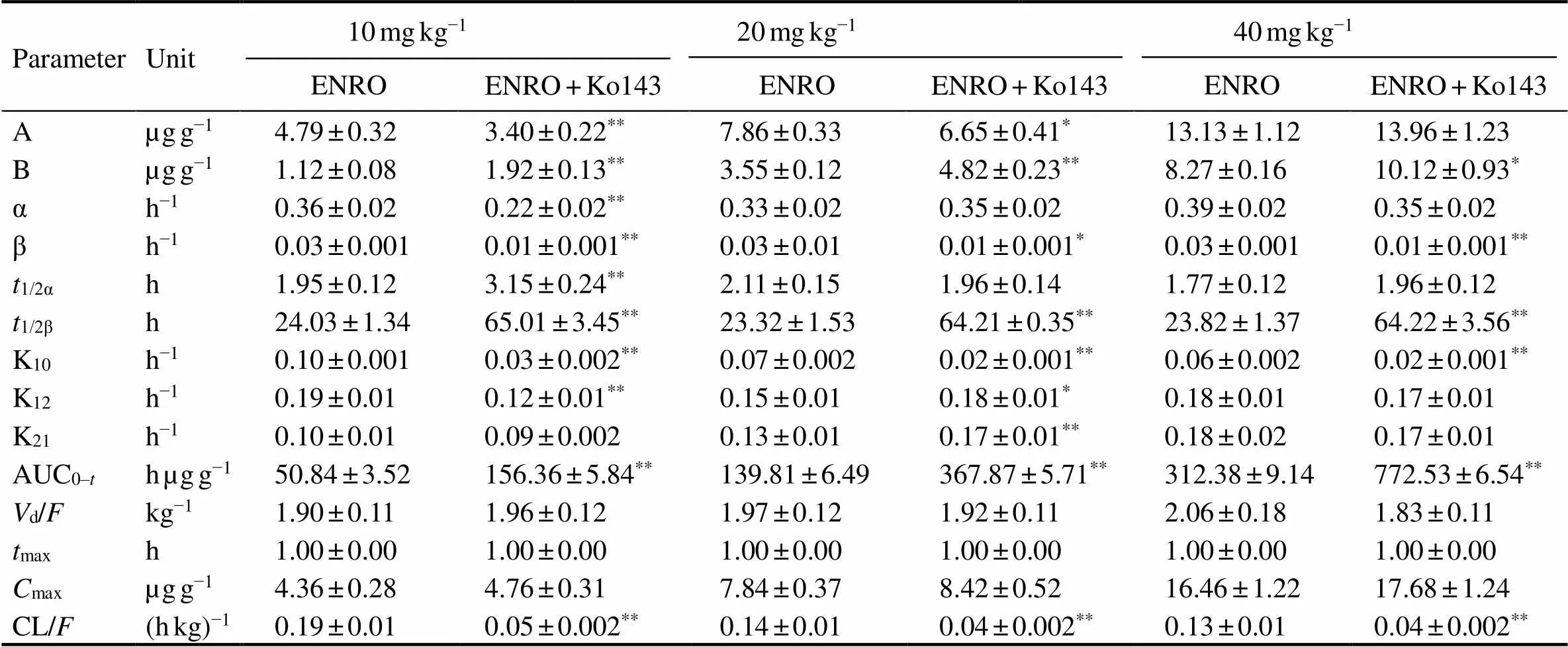

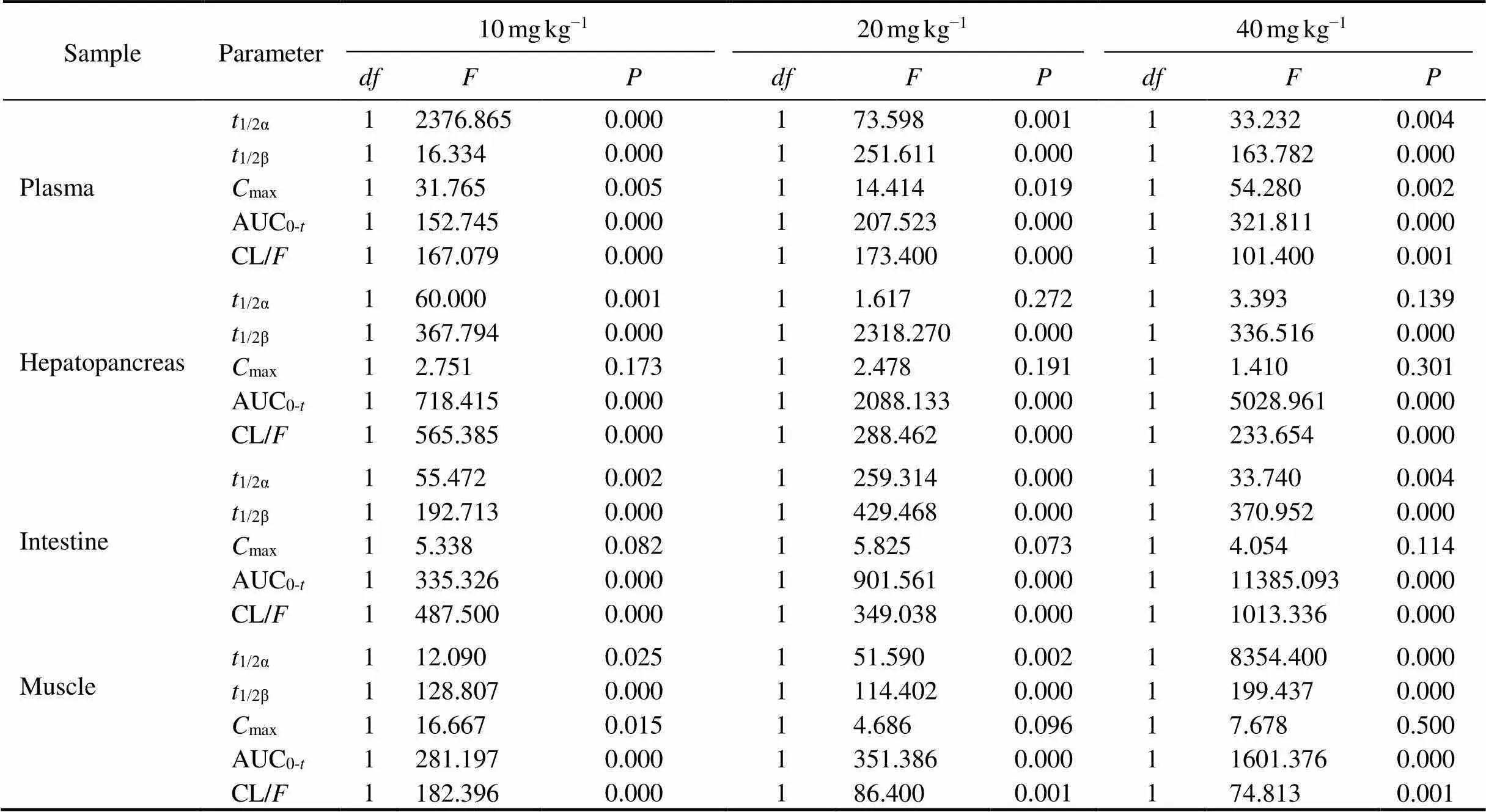

The mean plasma concentration-time profile of ENRO (10, 20, 40mgkg−1BW, p.o.) administered alone and co- administered with Ko143 (5mgkg−1BW, p.o.) is display- ed in Fig.3.The pharmacokinetic parameters are shown in Table 2. It was shown that orally taken both ENRO and Ko143 can significantly change ENRO pharmacokinetics in(<0.05) (Table 6). Compared with Ko143+ENRO groups, the concentration of ENRO in plas- ma was lower in ENRO-alone groups over the entire experimental period. Compared with ENRO-alone groups, a significant increase by 2.69-, 2.68-, and 2.72-folds in eli- mination half-life (t1/2β) for ENRO at concentrations of 10, 20 and 40mgkg−1BW were observed in Ko143 groups, respectively. In parallel, the area under the curve up to the last measurable concentration (AUC0-t) of ENRO increased significantly after concomitant administration of Ko143 (2.28-, 2.11- and 1.85-fold at ENRO doses of 10, 20 and 40mgkg−1BW, respectively,<0.01). The differences in distribution half-life (1/2α), peak concentration (max) and clearance (CL/) between two groups were also significant (<0.05).

Fig.3 The concentration-time profile of ENRO in plasma. The different curves are the plasma concentration-time profile of ENRO after single oral administration at 10, 20, 40mgkg−1 BW alone or together with Ko143. Data are shown as mean±SD (n=6).

Table 2 Pharmacokinetic parameters of enrofloxacin in plasma after oral administration at different doses alone or together with Ko143 in E. carinicauda (mean±SD, n=6)

Notes:*<0.05,**<0.01 significant difference between parameters of enrofloxacin in the presence and absence of Ko143 in the plasma of.max, time to reach peak concentration;max, peak concentration; AUC0–t, area under the curve up to the last measurable concentration;1/2α, distribution half-life;1/2β, elimination half-life;d, apparent volume of distribution per fraction of the dose absorbed; CL, clearance; K10, rate constants eliminate from the central chamber; K12, constant rate of transfer from central chamber to peripheral chamber; K21, rate constant of transfer from peripheral chamber to central chamber;α, distribution rate constant; β, elimination rate constant;, bioavailability.

Fig.4 The concentration-time profile of ENRO in different tissues. The concentration-time profiles of ENRO in the hepatopancreas (A), intestines (B) and muscles (C) after single oral administration at 10, 20, 40mgkg−1 BW alone or together with Ko143. Data are shown as mean±SD (n=6).

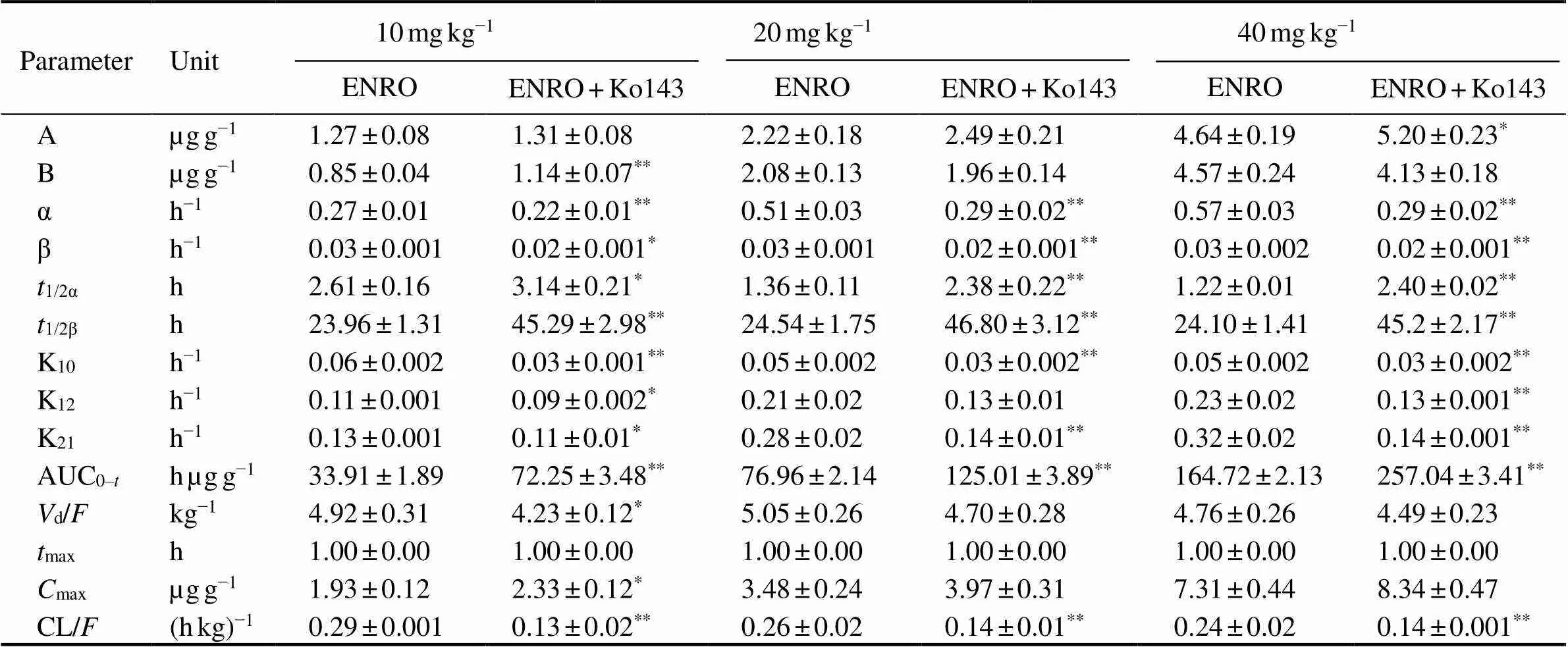

Table 3 Pharmacokinetic parameters of enrofloxacin in hepatopancreas after oral administration at different doses alone or together with Ko143 in E. carinicauda (mean±SD, n=6)

Note: Same as those in Table 2.

Table 4 Pharmacokinetic parameters of enrofloxacin in intestines after oral administration at different doses alone or together with Ko143 in E. carinicauda (mean±SD, n=6)

Note: Same as those in Table 2.

Table 5 Pharmacokinetic parameters of enrofloxacin in muscles after oral administration at different doses alone or together with Ko143 in E. carinicauda (mean±SD, n=6)

Note: Same as those in Table 2.

The mean concentration-time profile of ENRO (10, 20, 40mgkg−1BW, p.o.) in different tissues after administer- ed alone or co-administered with Ko143 (5mgkg−1BW, p.o.) are displayed in Fig.4, and pharmacokinetic para-meters are shown in Tables 3–5. The combination of ENRO and Ko143 caused also significant changes in the pharma- cokinetic behaviour of ENRO in hepatopancreas, intestine and muscleoral administration (<0.05) (Table 6). High ENRO concentrations over the whole drug-detec- tion period were observed, and a significant increase by 2.70–2.75, 2.68–2.70, 1.87–1.91 folds in the1/2β(<0.05) were displayed in hepatopancreas, intestine and muscle respectively at the dose of 10, 20 and 40mgkg−1 inKo143- treated groups compared with ENRO alone groups. In pa- rallel, the AUC0-tof ENRO significantly increased following concomitant administration of Ko143 (3.08-, 2.63-, 2.47-fold in hepatopancreas, 2.56-, 2.45-, 2.71-fold in in- testine, and 2.23-, 1.86-, 1.71-fold in muscle at the dose of 10, 20 and 40mgkg−1, respectively,<0.05). The difference in CL/between the ENRO group and Ko143+ENRO group also achieved statistical significance in he- patopancreas, intestine and muscle (<0.05). Although the differences in1/2αandmaxbetween the ENRO group and Ko143+ENRO group did not show statistical significance, they tended to be higher in the presence of Ko143.

Table 6 One-way ANOVA analysis of some pharma cokinetic parameters in plasma, hepatopancreas, intestine and muscle after oral administration at different doses alone or together with Ko143 in E. carinicauda

4 Discussion

Drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters belong to the crucial ‘detoxification system’ in the liver and small intestine, which cancontrol the absorption of xenobiotic compounds (including drugs) into the circulation (Wacher., 2001; Ding and Kaminsky, 2003; Murakami and Ta-kano, 2008). For drug candidates, low oral availability and high elimination rate can be ascribed to metabolism and/ or active efflux. Even for marketed drugs, oral availability and elimination rate can cause non-linearity and inter-per- son variations due to drug-drug interactions and genetic factors. Discovery of the effect of the metabolism enzymes and efflux transporters can help to select drug candidates and increase the safety and validity of drug treatment.

ABC transporters constitute one of the largest families of membrane transporter proteins, which couple the ener- gy stored in ATP to the movement of molecules across the membrane. ABC transporters have numerous functions and transport diverse substrates from simple ions, polar, amphipathic and hydrophobic organic molecules, to pep- tides, complex lipids and even small proteins. They are also involved in the absorption, accumulation and excre- tion of various toxic substances and play an important role in defence (Theodoulou and Kerr, 2015). To date, the ABC transporter superfamily has been divided into eight subtypes (A-H), of which P-gp (), MRP () and BCRP () are most involved in the metabolism and transport of exogenous chemicals (Xiong., 2010). BCRP is a multiple-specific ABC transporter synthesized at apical membranes in the intestines, liver, kidneys and placenta (Kusuhara and Sugiyama, 2007; Vlaming.,2009;Alexander., 2011). As an important efflux trans- porter, BCRP can transport food toxicants, nutrients and drugs, and thereby regulates the intestinal absorption and hepatic metabolism of these substances (Aspenström-Fa- gerlund., 2015). Considering the broad substrate spe- cificity of BCRP, its effect on drug disposition, including pharmacokinetics and oral bioavailability of drugs/drug can- didates are important factors for consideration.

Studies on mammals have demonstrated that BCRP can promote the elimination of drugs into bile and urine, and limit the penetration into tissues, which affects the pharmacokinetics of drugs (Enokizono., 2007;Vlaming., 2009). For example, BCRP is involved in the biliary excretion of quinolone antibiotics in mice. After administration of ciprofloxacin toknockout mice, the concentration of ciprofloxacin in renal tissue and blood in-knockout mice increased significantly (Ando., 2007). Ivermectin and danofloxacin can bind competitively to the BCRP transporter in sheep. Compared with single administration of danofloxacin, the concentration of dano- floxacin in sheep increased significantly.Meanwhile, the area under the curve of the drug in plasma increased by 32%–35%, and the half-life extended by 4%–52% when the two drugs were used in combination (Ballent.,2012). Moreover, when mice were treated (p.o.) with Ko143, a significant increase (greater than 2 folds;<0.05) of the specific BCRP substrate mitoxantrone (MXR) was found in liver. MXR level in blood (=0.17) and plasma (=0.13) also tended to increase in Ko143-treated mice thoughthe difference was not significant (Aspenström-Fagerlund., 2015). In engineered HeLa1A1 cells, Ko143 (5 and 20μmolL−1) administration led to a significant reduction in excretion of BCRP substrate cycloicaritin-3-O-glucuro- nide (15.6%–51.7%), efflux CLappvalue (32.3%–51.7%) and metabolized fraction(36.5%–44.1%), and a marked increase in intracellular level of glucuronide (35.2%–79.7%) (Li., 2018). The above findings also proved that drug disposition in mammals can be altered by changing the activity of BCRP.

It has been shown that BCRP is also present in shrimps, and its gene highly expressed in hepatopancreas and intestines (Zhou., 2009; Zhai., 2017). Additionally, ENRO is the most widely used fluoroquinolone in aquaculture (including shrimp culture) and a substrate for BCRPin mammals (Real., 2011; Liang., 2014). In consequence, we investigated the effects of Ko143 on BCRP activities and the influence of BCRP activity on ENRO pharmacokinetics in,which is help-ful to clarify the role of BCRP in drug disposition in shrimps. The findings of our study are in accordance with the previously reported about the role of BCRP in drug disposition in mammals (Ando., 2007; Ballent., 2012; Aspenström-Fagerlund., 2015; Li., 2018). The present study also demonstrated BCRP is a key factor that affects ENRO (which was giventhe oral route)pharmacokinetics in. Under the experimen- tal conditions, it was found that Ko143 down-regulated the mRNA abundance ofgene transcripts in. Then, the ENRO concentrations in plasma, hepatopancreas, intestines and muscles after ENRO (10, 20 and 40mgkg−1BW, p.o.) administration towas measured. We found that concurrent administration of Ko143 altered the pharmacokinetic parameters of ENRO,1/2β, AUC0-tand CL/significantly. Alteration of these pharmacokinetic parameters may be due to theenhancement of intestinal absorption,as well as the inhibition of hepatopancreas elimination of ENRO by inhibition ofgene expression using Ko143 (Vlaming., 2009; Gu., 2012; Aspenström-Fagerlund., 2015). Pharmacokinetic parameters such as1/2β, AUC0-tand CL/of ENRO in the edible tissue (muscle) were also increased significantly by co-administration with Ko143. This may be due to prolonged elimination of ENRO in the he- patopancreas and increased absorption of ENRO in the in- testines, which caused a slow elimination of ENRO in blood.Therefore, drug-drug interactions caused by change of BCRP activity should be concerned if ENRO is used incombination with other drugs and food ingredients; BCRP plays an important role in ENRO disposition in shrimps.

Presently, the effect of Ko143 on the mRNA abundance ofgene transcripts inwas studied in this research. The effect on the protein level will be studied once the antibody for the detection of BCRP is available.

5 Conclusions

Ko143 inhibited the expression ofgene significantly in. Co-administration of Ko143 in- creased the ENRO concentration significantly inand changed the pharmacokinetic parameters of ENRO administeredthe oral route, causing higher1/2α,1/2β, AUC0-tandmaxvalues, as well as lower CL/value in comparison with those of control. Concomitant application of Ko143 with ENRO resulted in major interactionsBCRP in. Thus, if ENRO is used in combination with other substances that can affect BCRP in shrimps, the change in ENRO pharmacokinetics should be considered.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foun- dation of Shandong Province, P. R. China (No. ZR2019 QC015), the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2019YFD0900403), the Central Public-Interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, CAFS (Nos. 2019ZD09 03 and 2020TD46), the Marine S&T Fund of Shandong Province for Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Sci- ence and Technology (Qingdao) (No. 2018SDKJ0502-2), the Earmarked Fund for Modern Agro-industry Technology Research System (No. CARS-48), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31873039).

Alexander, S. P., Mathie, A., and Peters, J. A., 2011. Guide to receptors and channels (GRAC), 5th edition., 164: S1-324.

Allen, J. D., van Loevezijn, A., Lakhai, J. M., van der Valk, M., van Tellingen, O., Reid, G., Schellens, J. H., Koomen, G. J., and Schinkel, A. H., 2002. Potent and specific inhibition of the breast cancer resistance protein multidrug transporterand in mouse intestine by a novel analogue of fumitremorgin C., 1: 417-425.

Ando, T., Kusuhara, H., Merino, G., Alvarez, A. I., Schinkel, A. H., and Sugiyama, Y., 2007. Involvement of breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) in the biliary excretion mechanism of fluoroquinolones., 35: 1873-1879.

Aspenström-Fagerlund, B., Tallkvist, J., Ilbäck, N. G., and Glynn, A. W., 2015. Oleic acid increases intestinal absorption of the BCRP/ABCG2 substrate, mitoxantrone, in mice., 237: 133-139.

Ballent, M., Lifschitz, A., Virkel, G., Sallovitz, J., Maté, L., and Lanusse, C., 2012.andassessment of the interaction between ivermectin and danofloxacin in sheep., 192: 422-427.

Bertilsson, G., Heidrich, J., Svensson, K., Asman, M., Jendeberg, L., Sydow-Bäckman, M., Ohlsson, R., Postlind, H., Blomquist, P., and Berkenstam, A., 1998. Identification of a human nuclear receptor defines a new signaling pathway for CYP3A in- duction., 95: 12208-12213.

Chang, Z. Q., Li, J., Liu, P., Kuo, M. M. C., He, Y. Y., Chen, P., and Li, J. T., 2012. cDNA cloning and expression profile analysis of an ATP-binding cassette transporter in the hepatopancreas and intestine of shrimp., 365-367: 250-255.

Daood, M., Tsai, C., Ahdab-Barmada, M., and Watchko, J. F., 2008.ABC transporter (P-gP/ABCB1, MRP1/ABCC1, BCRP/ABCG2) expression in the developing human CNS., 39: 211-218.

Ding, X., and Kaminsky, L. S., 2003. Human extrahepatic cyto- chromes P450: Function in xenobiotic metabolism and tissue- selective chemical toxicity in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts., 43: 149-173.

Duan, Y. F., Liu, P., Li, J. T., Li, J., and Chen, P., 2013. Expression profiles of selenium dependent glutathione peroxidase and glutathione S-transferase fromin response toand WSSV challenge., 35: 661-670.

Duan, Y. F., Liu, P., Li, J. T., Wang, Y., Li, J., and Chen, P., 2014. A farnesoic acid O-methyltransferase (FAMeT) fromis responsive toand WSSV challenge., 19: 367-377.

Enokizono, J., Kusuhara, H., and Sugiyama, Y., 2007. Effect of breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp/Abcg2) on the disposition of phytoestrogens., 72: 967-975.

Eriksson, U. G., Dorani, H., Karlsson, J., Fritsch, H., Hoffmann, K. J., Olsson, L., Sarich, T. C., Wall, U., and Schützer, K. M., 2006. Influence of erythromycin on the pharmacokinetics of ximelagatran may involve inhibition of P-glycoprotein-me- diated excretion., 34: 775- 782.

Gu, L. L., Chen, Z. X., and Lu, W. G., 2012. Advance on efflux inhibititors inhibiting ABC transporters to improve drug intestinal absorption., 33: 176-182 (in Chi- nese with English abstract).

Hua, W. J., Hua, W. X., and Fang, H. J., 2012. The role of OATP1B1 and BCRP in pharmacokinetics and DDI of novel statins., 30: e234-241.

Jonker, J. W., Merino, G., Musters, S., van Herwaarden, A. E., Bolscher, E., Wagenaar, E., Mesman, E., Dale, T. C., and Schin- kel, A. H., 2005. The breast cancer resistance protein BCRP (ABCG2) concentrates drug and carcinogenic xenotoxins into milk., 11: 127-129.

Kruijtzer, C. M., Beijnen, J. H., Rosing, H., ten Bokkel Huinink, W. W., Schot, M., Jewell, R. C., Paul, E. M., and Schellens, J. H., 2002. Increased oral bioavailability of topotecan in combination with the breast cancer resistance protein and P-gly- coprotein inhibitor GF120918., 20: 2943-2950.

Kusuhara, H., and Sugiyama, Y., 2007. ATP-binding cassette, sub- family G (ABCG family)., 453: 735-744.

Li, J. T, Han, J. Y., Chen, P., Chang, Z. Q., He, Y. Y., Liu, P., Wang, Q. Y., and Li, J., 2012. Cloning of a heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) gene and expression analysis in the ridgetail white prawn., 32: 1191-1197.

Li, S., Xu, J., Yao, Z., Hu, L., Qin, Z., Gao, H., Krausz, K. W., Gon- zalez, F. J., and Yao, X., 2018. The roles of breast cancer re- sistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) and multidrug resistance- associated proteins (MRPs/ABCCs) in the excretion of cycloi-caritin-3-O-glucoronide in UGT1A1-overexpressing HeLa cells., 296: 45-56.

Liang, J. P., Li, J., Li, J. T., Liu, P., Chang, Z. Q., and Nie, G. X., 2014. Accumulation and elimination of enrofloxacin and its metabolite ciprofloxacin in the ridgetail white prawnfollowing medicated feed and bath administration., 37: 508-514.

Maliepaard, M., Scheffer, G. L., Faneyte, I. F., van Gastelen, M. A., Pijnenborg, A. C., Schinkel, A. H., van De Vijver, M. J., Scheper, R. J., and Schellens, J. H., 2001. Subcellular locali- zation and distribution of the breast cancer resistance protein transporter in normal human tissues., 61: 3458- 3464.

Matsson, P., Pedersen, J. M., Norinder, U., Bergstrom, C. A., and Artursson, P., 2009. Identification of novel specific and general inhibitors of the three major human ATP-binding cassette transporters P-gp, BCRP and MRP2 among registered drugs., 26: 1816-1831.

Murakami, T., and Takano, M., 2008. Intestinal efflux transporters and drug absorption., 4: 923-939.

Real, R., González-Lobato, L., Baro, M. F., Valbuena, S., de la Fuente, A., Prieto, J. G., Alvarez, A. I., Marques, M. M., and Merino, G., 2011. Analysis of the effect of the bovine adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporter G2 single nucleotide polymorphism Y581S on transcellular transport of ve- terinary drugs using new cell culture models., 89: 4325-4338.

Sooud, K. A., 2003. Influence of albendazole on the disposition kinetics and milk antimicrobial equivalent activity of enrofloxacin in lactating goats., 48: 389- 395.

Staudinger, J. L., Goodwin, B., Jones, S. A., Hawkins-Brown, D., MacKenzie, K. I., LaTour, A., Liu, Y., Klaassen, C. D., Brown, K. K., Reinhard, J., Willson, T. M., Koller, B. H., and Kliewer, S. A., 2001. The nuclear receptor PXR is a lithocholic acid sensor that protects against liver toxicity., 98: 3369-3374.

Theodoulou, F. L., and Kerr, I. D., 2015. ABC transporter research: Going strong 40 years on., 43: 1033-1040.

Vlaming, M. L., Lagas, J. S., and Schinkel, A. H., 2009. Phy- siological and pharmacological roles of ABCG2 (BCRP): Re- cent findings in Abcg2 knockout mice., 61: 14-25.

Wacher, V. J., Salphati, L., and Benet, L. Z., 2001. Active secretion and enterocytic drug metabolism barriers to drug absorption., 46: 89-102.

Wang, L. Y., Li, F. H., Wang, B., and Xiang, J. H., 2013. A new shrimp peritrophin-like gene frominvolved in white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) infection., 35: 840-846.

Wright, J. A., Haslam, I. S., Coleman, T., and Simmons, N. L., 2011. Breast cancer resistance protein BCRP (ABCG2)-me- diated transepithelial nitrofurantoin secretion and its regulation in human intestinal epithelial (Caco-2) layers., 672: 70-76.

Xiong, J., Feng, L., Yuan, D., Fu, C., and Miao, W., 2010. Genome-wide identification and evolution of ATP-binding cassette transporters in the ciliate: A case of functional divergence in a multigene family., 10: 330.

Zhai, Q. Q., Li, J., and Chang, Z. Q., 2017. cDNA cloning, cha- racterization and expression analysis of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transmembrane transporter in., 48: 4143-4154.

Zhou, J., He, W. Y., Wang, W. N., Yang, C. W., Wang, L., Xin, Y., Wu, J., Cai, D. X., Liu, Y., and Wang, A. L., 2009. Molecular cloning and characterization of an ATP-binding cassette (ABC)transmembrane transporter from the white shrimp., 150: 450-458.

. E-mail: zqq0817@163.com

E-mail: lijian@ysfri.ac.cn

August 14, 2019;

October 21, 2019;

May 11, 2020

(Edited by Qiu Yantao)

杂志排行

Journal of Ocean University of China的其它文章

- Phaeocystis globosa Bloom Monitoring: Based on P. globosa Induced Seawater Viscosity Modification Adjacent to a Nuclear Power Plant in Qinzhou Bay, China

- Effect of pH, Temperature, and CO2 Concentration on Growth and Lipid Accumulation of Nannochloropsis sp. MASCC 11

- Fuzzy Sliding Mode Active Disturbance Rejection Control of an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle-Manipulator System

- The 9–11 November 2013 Explosive Cyclone over the Japan Sea- Okhotsk Sea: Observations and WRF Modeling Analyses

- Real-Time Position and Attitude Estimation for Homing and Docking of an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Based on Bionic Polarized Optical Guidance

- Characterization of the Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Arius dispar (Siluriformes: Ariidae) and Phylogenetic Analysis Among Sea Catfishes