阿司匹林等环氧化酶抑制剂对食管癌发病风险影响的系统评价与Meta分析

2020-08-04张斯渊董信春韩松辰

张斯渊 董信春 韩松辰

[摘要] 目的 系统评价阿司匹林等环氧化酶抑制剂(COX抑制剂)对食管癌发病风险的影响,以阐明两者间的关系。方法 通过检索PubMed、EMBASE、Cochrane library、CNKI数据库,搜索关于使用阿司匹林/NSAIDs与食管癌发病风险影响的临床研究,使用Stata24.0软件进行Meta分析。 结果 使用COX抑制剂可降低人群患食管癌/食管高度异型增生风险[相对风险RR=0.64,95%CI(0.53~0.77),P=0.512],阿司匹林同样能够降低人群患食管癌/食管高度异型增生的风险[RR=0.63,95%CI(0.43~0.94),P=0.642],非阿司匹林环氧化酶抑制剂也有效果[RR=0.50,95%CI(0.32~0.78),P=0.492],这种化学性预防食管癌作用可能与用药时间相关。 结论 使用阿司匹林/COX抑制剂可以有效降低食管癌的发生率,但目前报道的相关文献仍然较少,需要更多高质量的研究来佐证。

[关键词] 阿司匹林;COX抑制剂;食管癌;发病风险

[中图分类号] R735.1 [文献标识码] A [文章编号] 1673-9701(2020)15-0022-08

Systematic evaluation and Meta-analysis of the effect of cyclooxygenase inhibitors like aspirin on the risk of esophageal cancer

ZHANG Siyuan1, 2 DONG Xinchun2 HAN Songchen2 JIN Dacheng1, 2 WANG Bing1, 2 CHEN Meng1, 2 GOU Yunjiu2

1.Gansu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Lanzhou 730000, China; 2.Department of Thoracic Surgery, Gansu Provincial People's Hospital, Lanzhou 730000, China

[Abstract] Objective To systematically evaluate the effect of cyclooxygenase inhibitors(COX inhibitors) like aspirin on the risk of esophageal cancer, to clarify the relationship between the two. Methods By searching PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CNKI database, clinical studies of the effect of aspirin/NSAIDs use on the risk of esophageal cancer were searched. Meta analysis was performed using Stata24.0 software. Results The use of COX inhibitors can reduce the risk of esophageal cancer/esophageal high-grade dysplasia[relative risk RR=0.64, 95%CI(0.53-0.77), P=0.512]. Aspirin can also reduce the risk of esophageal cancer/high-grade esophageal dysplasia[RR=0.63, 95%CI(0.43-0.94), P=0.642]. Non-aspirin cyclooxygenase inhibitors also had an effect[RR=0.50, 95% CI(0.32-0.78), P=0.492]. The effect of chemical prevention of esophageal cancer may be related to the time of medication. Conclusion The use of aspirin/COX inhibitors can effectively reduce the incidence of esophageal cancer, but there are still relatively few relevant literatures reported, and more high-quality studies are needed to corroborate them.

[Key words] Aspirin; COX inhibitors; Esophageal cancer; Risk of onset

目前,全球1270萬新增癌症病例中有760万人死于癌症[1],而根治性手术仍然是目前的首选治疗方法[2]。胃癌和食管癌是全球第三和第八大常见癌症,分别占癌症总发病率的6.8%和3.2%[3],且预后不良(胃癌的5年生存率为29%,食管癌为20%)[4]。鉴于各类癌症,尤其是食管癌的高发病率及致死率的迅速增加,寻求丰富多样的治疗方式迫在眉睫,而这其中,应用潜在的化学预防药物是非常必要的。

临床上,阿司匹林作为大剂量止痛药及预防心血管疾病的抗血小板药物而广泛应用,剂量1w单位(通常约75 mg)[5]。对于阿司匹林等COX抑制剂的多途径、多功能药用研发成为目前临床多学科诊疗疾病的新趋势,这其中,预防性治疗食管癌便成为胸外科学的热门研究课题。当前,诸多研究(包括三项Meta分析)都支持临床上应用如环氧化酶(COX)抑制剂、阿司匹林、非选择性非甾体抗炎药(nsNSAIDs)和选择性COX-2抑制剂进行化学预防的潜力[6-8]。同样的,也有研究不支持此结论,认为预防性使用阿司匹林/NSAIDs会增加食管癌发病风险[9]。可以看出,由于结果的不尽相同,大家褒贬不一。因此,本研究采用Meta分析的方法进行综合评价,以期对阿司匹林/COX抑制剂能否降低食管癌发病风险进行客观评价。

1 资料与方法

1.1 纳入与排除标准

1.1.1 研究类型 病例对照研究/队列研究(前瞻性、回顾性)。

1.1.2 研究对象 食管癌高发地区如澳大利亚、英国、美国洛杉矶等具有高发病风险患者。

1.1.3 干预措施 暴露组服用阿司匹林/NSAIDs,非暴露组未采取任何干预措施。

1.1.4 结局指标 服药后食管癌发病风险是否下降。

1.1.5 纳入标准 符合以下所有的纳入标准,则纳入研究:(1)评估暴露于COX抑制剂、阿司匹林或两者兼备的情况;(2)测定食管癌的发生、诊断或死亡情况;(3)报告用有置信区间的相对风险或优势比(ORs),或有足够的数据可进行计算。纳入研究不受研究规模、语言或出版物类型的限制。

1.2 文献检索

计算机检索PubMed、EMBASE、Cochrane library、CNKI数据库,手工检索文献补充。检索时限为自建库至2019年9月。其中,手工检索采用主题词加自由词的检索方式,中文检索词包括:食管癌、阿司匹林、非甾体抗炎药、COX抑制剂、风险等;英文检索词包括:Esophagus/Esophageal Cancer(s),Esophagus/Esophageal Neoplasm(s),Cancer(s)/Neoplasm(s)of Esophagus/Esophageal,Cyclooxygenase inhibitor(s),Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug(s),NSAID(s),Aspirin,risk(s)。以PubMed为例,具体检索策略如下:#1 Esophagus Cancer,#2 Esophageal Cancer,#3 Esophagus Neoplasm,#4 Esophageal Neoplasm,#5 Cancer of Esophagus,#6 Neoplasm of Esophagus,#7 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6,#8 Aspirin,#9 Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug,#10 NSAID,#11 Cyclooxygenase inhibitor,#12 #7 #8 or #9 or #10,#13 Risk,#7 and #11 and #13。

1.3 文献筛选、数据提取

两名研究人员独立筛选文献并提取数据进行讨论,不受出版物发表年份、作者和期刊的影响。数据提取主要包括:①用药类型、使用频率、暴露信息源(如问卷调查、访谈、药房数据库等);②混杂因素:包括年龄、体重、饮食、吸烟史、饮酒史、家族史等;③结局指标:未发病人口数。

1.4 发表偏倚

如果纳入文献数量大于10篇则需要进行发表偏倚的评估,本研究纳入文献少于10篇[10]。

1.5 文献质量评价

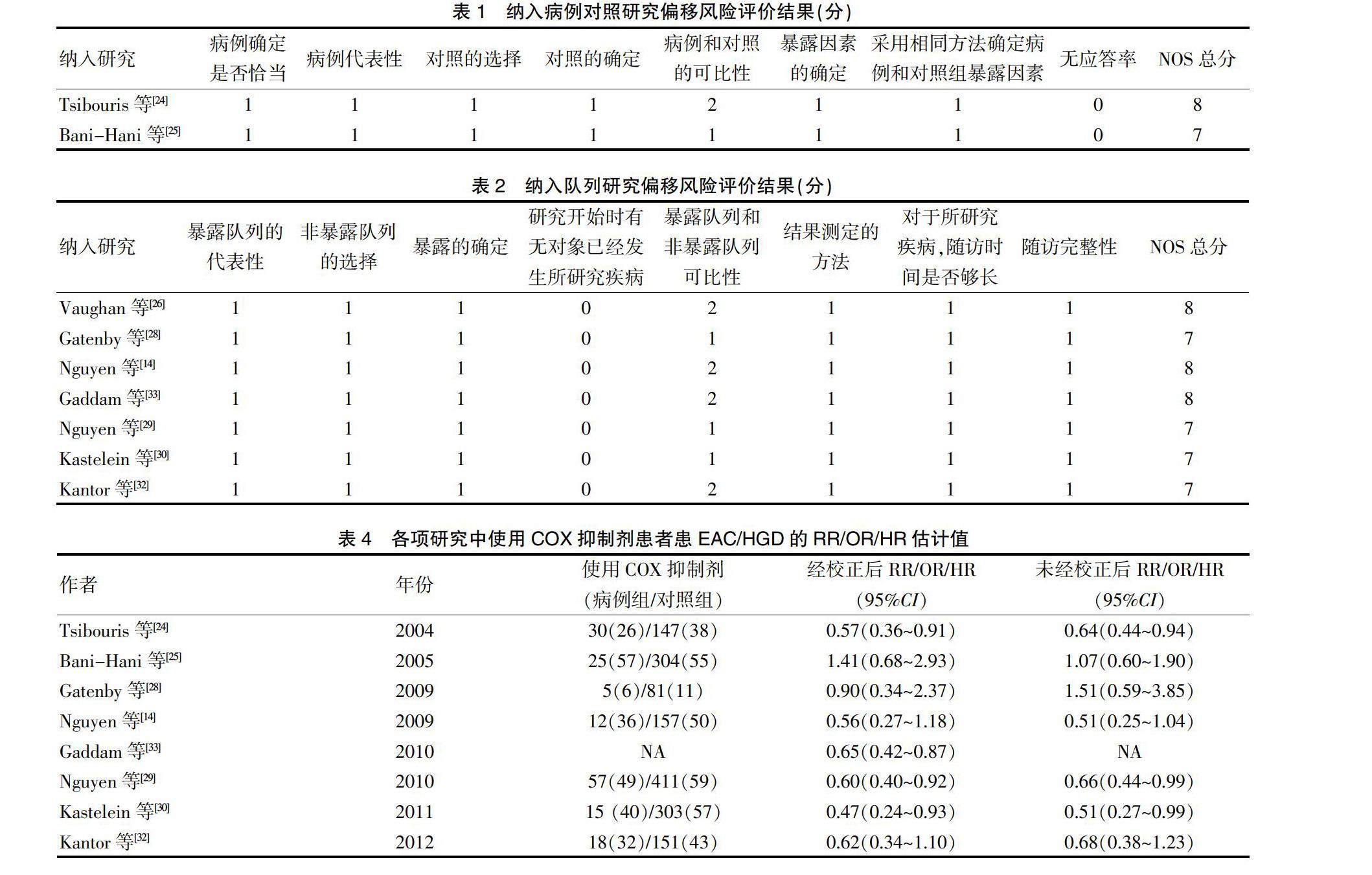

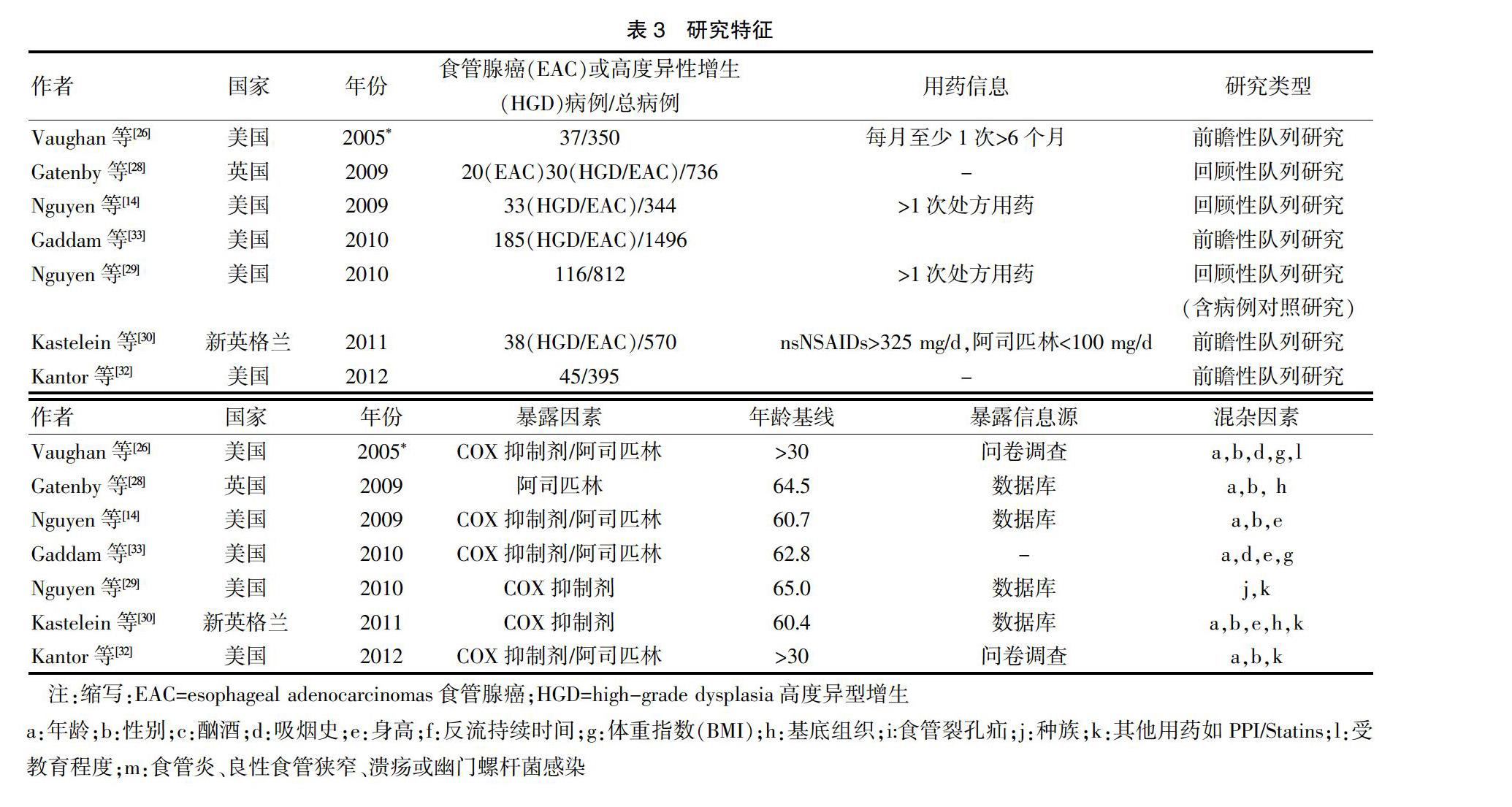

本次纳入文献包含2篇病例对照研究[24-25]和7篇队列研究[14,26,28-29,30,32-33],针对不同研究类型文獻偏移风险,我们采用NOS量表评分标准分别进行评估。其中病例对照研究评价内容包括:病例确定是否恰当、病例代表性、对照的选择、对照的确定、病例和对照的可比性、暴露因素的确定、采用相同方法确定病例和对照组暴露因素、无应答率等,见表1。队列研究评价内容包括:暴露队列的代表性、非暴露队列的选择、暴露的确定、研究开始时有无对象已发生所研究疾病、暴露队列和非暴露队列可比性、结果测定的方法,对于所研究疾病随访时间是否够长、随访完整性等,见表2。

1.6 统计学分析

使用Stata24.0软件进行统计学分析。采用相对危险度(RR)、比值比(OR)、95%置信区间(CI)评价统计学效应。根据固定效应和随机效应模型的假设,运用Mantel-Haenszel方法计算总的OR估算值:如果结果一致,则采用固定效应模型;否则,应使用德西蒙尼和莱尔德方法的随机效应模型[11-14]。采用Q和I2统计量检验研究之间的统计学异质性[15]。针对混杂因素校正后的数据的汇总估算值使用每个研究报告的校正后估算值。表3中描述每个研究所包含的混杂因素。除非另有说明,否则所有报告的汇总估算值仅使用具有校正数据的研究。

1.7 异质性评估

Q检验中,P<0.1便认为异质性具有统计学意义。I2为研究之间变异相对总变异的贡献比例,分别为25%、50%和75%,代表低、中、高异质性[15,16]。为了尽可能避免潜在的异质性,我们采取如下措施,效果显著。首先,在随机试验中,实验组只有进行随机化和盲法分配,才足以影响实验结果,虽然观察性研究的信息很少[17-19],但组间基线差异可能会混淆观察性研究的结果。因此,我们使用每个作者的报告(或计算)RR/OR/HR值,并对可变混杂因素进行校正,以计算汇总估计的RR值。其次,我们通过每次单独省略一项研究来进行敏感性分析,来评估合并后的估计值与包含所有研究结果相比,是否在统计学上有显著变化。第三,通过研究设计(病例对照研究和队列研究;回顾性和前瞻性)、药物治疗类型(阿司匹林与非阿司匹林COX抑制剂)、COX抑制剂使用时间(短时间与长时间)等因素进行亚组分析[17-23]。

2 结果

2.1 文献筛选流程

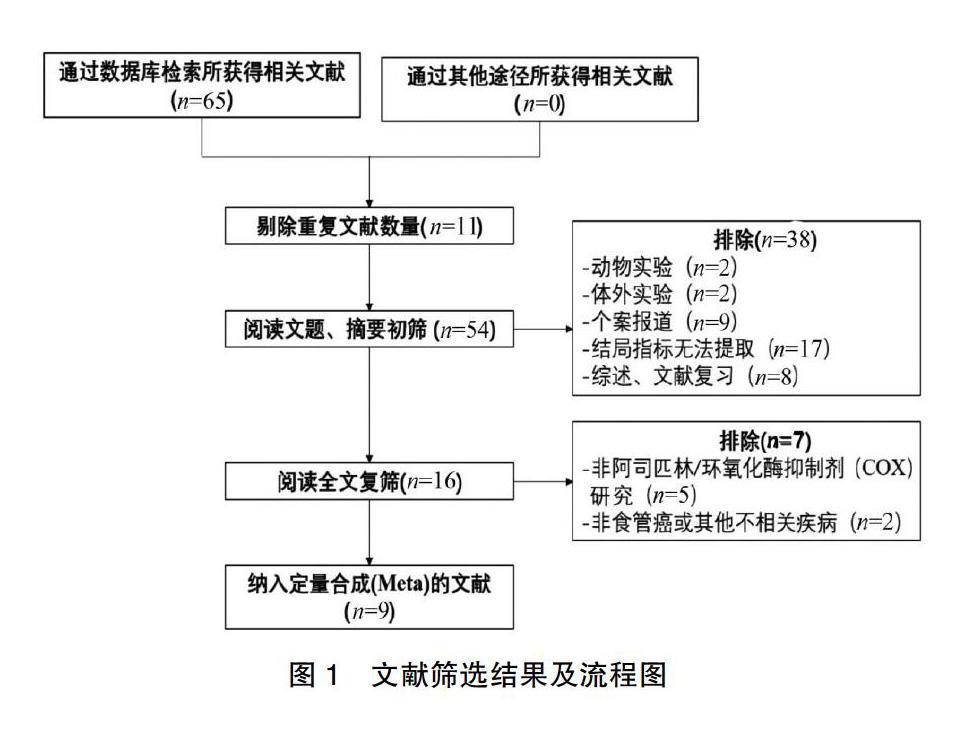

通过筛选,初筛65篇文献,运用EndNote X9软件剔重后保留文献54篇。通过精读标题、摘要及全文浏览,保留文献9篇[24-32],其中病例对照研究2篇,前瞻性队列研究6篇以及包含有病例对照研究的队列研究(根据特点归于队列研究)1篇,具体流程见图1。

2.2纳入研究基本特征

本篇共纳入5796名参与者,其中662名被诊断为EAC或HGD。其中有2篇文章是由同一作者发表的,但人数相同。在对COX抑制剂的整体使用进行Meta分析时,选择2012年发表的文章,而2005年发表的文章中的数据仅用于药物类型和持续时间反应的亚组分析。

2.3 Meta分析结果

2.3.1 癌症进展(全部类型的COX抑制剂) 总体而言,相比于对照组,使用COX抑制剂的比例更小(38.6%和39.7%)。所有接触过COX抑制剂的患者发生EAC/HGD的风险均显著降低(校正RR=0.64,95%CI=0.53~0.77,P异质性=0.512)。同时计算了未校正RR(未校正RR=0.70,95%CI=0.56~0.86,P异质性=0.357)。此后每次省略一项研究,以了解是否会在幅度、统计显著性或异质性发生实质性的变化。但没有任何研究显著地影响总体估计结果。其中的5项研究仅使用EAC作为结果,见表3、表4。因此对这些研究进行亚组分析,结果显示EAC的进展风险显著降低(校正RR=0.70,95%CI=0.52~0.95,P异质性=0.238),见图2。

2.3.2 研究设计 经计算,队列研究的校正估计值(校正RR=0.61,95%CI=0.49~0.76,P异质性=0.929)与病例对照研究的校正估计值不同(校正RR=0.86,95%CI=0.35~2.07,P异质性=0.04),差异无统计学意义,见图3。在6项队列研究中,3例为回顾性,3例为前瞻性。因此进行敏感性分析,以判断回顾性队列研究(校正RR=0.62,95%CI=0.44~0.87,P异质性=0.718)和前瞻性队列研究之间的差异(校正RR=0.61,95%CI=0.46~0.81,P异质性=0.709)。

2.3.3 用药时间 为了探索用药时间产生的效应,我们在已提供用药时间影响风险估计的研究中进行了亚组分析。由于各项研究对于“较长用药时间”的定义差别较大(2个月、1年、2年、3年甚至5年),因此我们将1年、2年和3年定义为“较长用药时间”,并进行了亚组分析,见表5。

结果显示,相较于与用药时间<1年(校正RR=0.67,95%CI=0.46~0.97,P异质性=0.674),使用环氧合酶抑制剂治疗>1年的风险显著降低(校正RR=0.54,95%CI=0.36~0.79,P异质性=0.999)。相较于与更长的用药时间(<2年)(校正RR=0.67,95%CI=0.46~0.97,P异质性=0.674),使用环氧合酶抑制剂治疗>2年的风险降低更加显著(校正后的RR=0.53,95%CI=0.33~0.87,P异质性=0.992)。此外,相较于与用药时间<3年(校正RR=0.64,95%CI=0.46~0.90,P异质性=0.751),使用环氧合酶抑制剂治疗>3年发生EAC/HGD风险降低更加显著(校正RR=0.54,95%CI=0.30~0.99,P异质性=0.952)。三组之间的差异均无统计学意义。

2.3.4 药物类型 虽然Vaughan等[26]的研究未对COX抑制剂使用进行总体分析,但我们将其纳入了药物类型的亚组分析。我们从相关研究中提取阿司匹林和非阿司匹林COX抑制剂的风险评估,共有四项研究提供阿司匹林對潜在混杂因素的评估[24,26,28,30],见表5。结果显示,任何与阿司匹林接触的人群均与肿瘤进展风险降低相关(校正RR=0.63,95%CI=0.43~0.94,P异质性=0.642),见图4。只有三项研究提供非阿司匹林COX抑制剂的校正估计值[24,26,30]。结果表明暴露于任何类型的非阿司匹林COX抑制剂患者的EAC/HGD风险也显著降低(校正RR=0.50,95%CI=0.32~0.78,P异质性=0.492),见图4。

2.3.5 同时使用其他药物为研究用药 期间,同时使用其他化学预防药物如质子泵抑制剂(PPIs)和他汀类药物(Statins)的相互作用所产生效果,将分析限制在根据这些额外药物的使用进行校正的研究中[14,30,32],并与未校正的结果进行比较[24,25,29,33]。结果显示,PPIs/Statins校正比未校正风险下降42%(校正RR=0.58, 95%CI=0.43~0.78,P异质性=0.801),高于未校正值(RR=0.70, 95%CI=0.53~0.93,P异质性=0.285),差异无统计学意义(P异质性=0.38)。

2.3.6 非处方药物使用 COX抑制剂属常见非处方药。因此,我们想了解非处方药物的使用是否会影响整体结果。在所纳入的个别研究中[30,32],我们前瞻性地收集药用信息,所有药用信息都会进行药房记录,并交叉核对。相关药用信息是通过回顾性问卷调查收集的,包括非处方药使用的信息。这些信息认为经济状况差异导致不同阶层人群会在不同药房购买处方/非处方药。因此,作者针对患者社会经济状况进行多元分析并校正。然而,其他纳入研究未能解决该问题[14,24,25]。因此,我们在包括非处方药使用在内的五项研究中进行Meta分析,仍发现使用COX抑制剂的风险显著降低(RR=0.64,95%CI=0.48~0.86,P异质性=0.229)。这说明非处方药的使用对整体结果影响不大。

3讨论

从美国对过去20年世界食管癌发病率趋势统计看[34-36],人群中食管鱗状细胞癌的发病率下降了1/3,但腺癌的发病率增加了6倍。临床中,能够增加食管癌发病风险的疾病有很多,其中Barrett食管与胃食管反流病(GERD)最为典型。研究显示[37-39],长期站立的GERD患者长期的反流症状使食管腺癌的风险增加了近25%,而相比于同年龄层人群,Barrett食管患者患食管癌的风险提高了30~125倍。因此,鉴于发病率的剧增、晚期的诊断、治疗的不良反应和极低的存活率,发掘应用潜在的化学预防药物迫在眉睫。有大量证据表明,经常使用非甾体抗炎药(NSAIDs),特别是阿司匹林,可以降低结直肠腺瘤的发生率[40-43]。但是,对于食管癌、胃癌等上消化道癌症的抑制作用却缺乏证据加以系统探讨和证明。此篇Meta分析中,我们整合了先前多项大型调查研究结果,发现使用阿司匹林等COX抑制剂与高风险患者癌症进展风险呈现显著负相关:总风险下降36%,EAC风险下降30%。

在队列研究中,可以观察到风险明显降低(降低39%),而在病例对照研究中却没有,这可能是由于在回忆或注册时产生误差所致或者在病例对照研究的研究对象数量太少,结果缺乏可信性。通过对队列研究进行分析,认为队列研究的研究设计并不影响最终结果,相反,这些结果扩展了先前的回顾性和前瞻性研究。按照药物类型分层分析,肿瘤进展与低剂量阿司匹林(减少37%)和非阿司匹林COX抑制剂(减少50%)之间呈负相关,使用非阿司匹林COX抑制剂似乎比使用低剂量阿司匹林对降低食管癌发病风险更有效,但这需要更进一步的研究,以确定最佳的COX抑制剂。

虽纳入研究的个体数量较多,但进行亚组分析时所纳入的文献数量屈指可数。例如,在研究用药剂量效应和频率效应时,只有3项纳入的研究提供剂量和频率的风险估计,故虽然结果反映用药频率与保护作用呈正相关,但很难得出有说服力的剂量效应和频率效应结论。同时,在研究COX抑制剂的用药时间效应中,只纳入5项研究,且这些研究对“较长时间”的概念分类从2个月到5年不等。因此我们将1年、2年和3年定义为“较长用药时间”,并进行亚组分析。在较长用药时间和较短用药时间之间没有发现任何显著差异证明风险降低,这表明使用COX抑制剂可能与持续时间反应无关。由于Meta分析在方法学上具有局限性,以及各个纳入研究对用药时间长短的定义不尽相同,故无法通过Meta分析确定COX抑制剂的用药时间效应,这需要进一步探索人群中预防性使用COX抑制剂的最佳用药时间。

研究证明,目前COX抑制剂如阿司匹林、NSAIDs和选择性COX-2均被报道在细胞系和动物模型中发挥有益的抗癌作用[44-47]。此类药物可阻断花生四烯酸进入环氧化酶活性位点从而抑制环氧化酶的活性(包括构成COX-1和COX-2异构体的酶)[48,49],而COX是前列腺素合成的关键。这种酶的一个亚型COX-2通常在正常肠黏膜中缺失,但在癌前和恶性胃肠道肿瘤中过度表达。前列腺素是促进细胞生长的必需激素,且浓度越高,细胞生长越迅速[50,51]。阿司匹林可以减少GERD的炎性并发症的发生[52],本篇所纳入研究中还研究了NSAIDs与Barrett食管之间的关联[28,30-32]。Barrett食管是一种食管癌的癌前病变,与食管腺癌密切相关。主要原因包括在Barrett食管的形成和恶性发展过程中COX-2表达增加[53,54]。因此,阿司匹林可以通过预防Barrett食管的形成,延缓其进展,从而降低其进展为腺癌的可能性,以预防食管腺癌。

在肿瘤生长方面,COX酶可减少细胞粘附和凋亡,促进血管生成[55-57]。有研究表明,非整倍体克隆和TP53损伤的克隆的绝对值是食管癌进展的危险因素[58],遗传学方面,Galipeau等[59]研究发现非甾体抗炎药可能通过增加细胞凋亡、减少血管生成和增殖来减少克隆大小。通过增加细胞凋亡,非甾体抗炎药可能会减少可存活克隆的产生,从而减少多样性,限制自然选择作用的遗传编译库。此外,非甾体抗炎药还具有减少炎症的作用,从而降低克隆进化的突变率,减少细胞变异的数量。虽然COX抑制剂作为临床化学试剂应用前景良好,但此类药物具有抑制血管COX-2的药效学效应,易导致循环不良而出现如上消化道出血、消化性溃疡和出血性中风等疾病,如此肯定将阻碍其广泛应用[60,61]。所以,深入了解COX抑制剂等药物与体细胞遗传异常的相互作用,将有助于定位癌症靶点,筛查出高危人群尽早实施药物干预,避免无序盲目用药对身体造成损害,加速癌症进展。

文章局限性归纳如下:①本文纳入研究数量较少(上文已提及)且均为观察性研究,与随机对照试验相比,缺乏随机分配干预;②由于诸多混杂未予以测量,使用不同药物(PPIs/Statins),其他健康相关问题(心血管疾病等)和相关并发症,可能会导致结果产生较大扭曲和偏倚;③所纳入的研究可能存在反向因果关系。队列研究控制反向因果关系是为了避免普遍的或现有的癌症病例存在。在病例对照研究方面,Tsibouris等[24]指出,他们将EAC诊断前4年开始使用COX抑制剂的患者剔除,以避免收集潜在病理引起的用药数据,从而避免反向因果关系。因此,我们能够将这种反向因果关系的可能性降到最低;④如前文所讨论,我们没有通过Meta分析来平衡COX抑制剂带来的风险和效益。

综上所述,目前的研究进展不足以支撑阿司匹林等COX抑制剂的大规模预防性使用。我们期待更多如随机对照试验等高质量研究成果的发表以及更大的前瞻性研究,用更详备的数据来评估这一成果的降风险效果,为潜在的化学预防、产生更大的社会经济效益做贡献。

[参考文献]

[1] Jemal A,Center MM,Desantis C,et al. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends[J]. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention,2010,19(8):1893-1907.

[2] Otowa Y,Nakamura T,Takiguchi G,et al. Safety and benefit of curative surgical resection for esophageal squamous cell cancer associated with multiple primary cancers[J]. European Journal of Surgical Oncology,2016, 42(3):407-411.

[3] Ferlay J,Soerjomataram I,Dikshit R,et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide:Sources,methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012[J]. International Journal of Cancer,2015,136(5):E359-E386.

[4] Siegel RL,Fedewa SA,Miller KD,et al. Cancer statistics for Hispanics/Latinos,2015[J]. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians,2015,65(6):457-480.

[5] Blackwell L. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease:collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials[J]. Lancet,2010,373(9678):1849-1860.

[6] Sun Lei,Yu Shiying.Meta-analysis:Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma[J].Dis Esophagus,2011,24:544-549.

[7] Corley DA,Kerlikowske K,Verma R,et al. Protective association of aspirin/NSAIDs and esophageal cancer:A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Gastroenterology,2003,124(1):47-56.

[8] Abnet CC,Freedman ND,Kamangar F,et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of gastric and oesophageal adenocarcinomas:results from a cohort study and a meta-analysis[J]. British Journal of Cancer,2009,100(3):551-557.

[9] Farrow DC,Vaughan TL,Hansten PD,et al. Use of aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of esophageal and gastric cancer[J]. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention,1998,7(2):97-102.

[10] Egger M,Davey Smith G,Schneider M,et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test[J].BMJ,1997,315:629-634.

[11] Greenland S. Invited commentary:A critical look at some popular meta-analytic methods[J]. American Journal of Epidemiology,1994,140(3):290-296.

[12] Petitti DB. Meta-analysis,decision analysis,and cost-effectiveness analysis[J]. Statistics in Medicine,2000,123(2):650-651.

[13] Pignon JP,Poynard T. Meta-analysis of clinical trials[J].Gastroenterologie Clinique et Biologique,1991,15(3):229-238.

[14] Nguyen DM,Richardson P,Hashem B El-Serag. Medications(NSAIDs,Statins,Proton Pump Inhibitors)and the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett\"s esophagus[J]. Gastroenterology,2010,138(7):2260-2266.

[15] Higgins JPT,Thompson SG Higgins JPT,Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis[J]. Statistics in Medicine, 2002, 21(11):1539-1558.

[16] Higgins JPT. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses[J].BMJ,2003,327(7414):557-560.

[17] Chalmers TC,Celano P,Sacks HS,et al. Bias in Treatment Assignment in Controlled Clinical Trials[J]. New England Journal of Medicine,1984,309(22):1358-1361.

[18] Jadad AR,Moore RA,Carroll D,et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials:is blinding necessary?[J].Control Clin Trials,1996,17:1-12.

[19] Schulz KF,Chalmers I,Hayes RJ,et al. Empirical Evidence of Bias:Dimensions of Methodological Quality Associated With Estimates of Treatment Effects in Controlled Trials[J]. Journal of the American Medical Association,1995,273(5):408-412.

[20] Pocock RBSJ. Epidemiologic Research:Principles and Quantitative Methods.by D.G. Kleinbaum; L.L. Kupper;H. Morgenstern[J]. Biometrics,1983,39(3):822-823.

[21] Gerbarg ZB,Horwitz RI. Resolving conflicting clinical trials:Guidelines for meta-analysis[J]. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology,1988,41(5):503-509.

[22] Schulz KF,Chalmers I,Grimes DA,et al. Assessing the quality of randomization from reports of controlled trials published in obstetrics and gynecology journals[J]. JAMA The Journal of the American Medical Association,1994,272(2):125-128.

[23] Imperiale TF,Birgisson S. Somatostatin or octreotide compared with H2 antagonists and placebo in the management of acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage:A meta-analysis[J]. Annals of Internal Medicine,1997,127(12):1062-1071.

[24] Tsibouris P,Hendrickse MT,Isaacs PET. Daily use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is less frequent in patients with Barrett's oesophagus who develop an oesophageal adenocarcinoma[J]. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics,2004,20(6):645-655.

[25] Bani-Hani KE,Bani-Hani BK,Martin IG. Characteristics of patients with columnar-lined Barrett's esophagus and risk factors for progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma[J]. World Journal of Gastroenterology,2005,11(43):6807-6814.

[26] Vaughan TL,Dong LM,Blount PL,et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of neoplastic progression in Barrett's oesophagus:a prospective study[J]. Lancet Oncology,2005,6(12):945-952.

[27] De Jonge PJF,Steyerberg EW,Kuipers EJ,et al. Risk Factors for the Development of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma in Barrett\"s Esophagus[J]. The American Journal of Gastroenterology,2006,101(7):1421-1429.

[28] Gatenby PA,Ramus JR,Caygill CP,et al. Aspirin is not chemoprotective for Barrett's adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus in multicentre cohort[J]. European Journal of Cancer Prevention, 2009,18(5):381-384.

[29] Nguyen DM,El-Serag HB,Henderson L,et al. Medication Usage and the Risk of Neoplasia in Patients With Barrett\"s Esophagus[J]. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology,2009,7(12):1299-1304.

[30] Kastelein F,Spaander MC,Biermann K,et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and statins have chemopreventative effects in patients with Barrett's esophagus[J]. Gastroenterology,2000,141(6):2000-2008.

[31] Beales ILP,Vardi I,Dearman L. Regular statin and aspirin use in patients with Barretts oesophagus is associated with a reduced incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma[J]. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology,2012,24(8):917-923.

[32] Kantor ED,Onstad L,Blount PL,et al. Use of Statin Medications and Risk of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma in Persons with Barrett's Esophagus[J].Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention,2012,21(3):456-461.

[33] Gaddam S,Young PE,Wang A,et al. M1104 Predicting High-Grade Dysplasia(HGD)and esophageal adenocarcinoma(EAC) in patients with non-Dysplastic Barrett\"s Esophagus(BE):results from a large,multicenter cohort Study[J]. Gastroenterology,2010,138(5):S333.

[34] Younes M,Henson DE,Ertan A,et al. Incidence and survival trends of esophageal carcinoma in the United States:racial and gender differences by histological type[J].Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology,2002,37(12):1359-1365.

[35] Yang PC,Davis S. Incidence of cancer of the esophagus in the US by histologic type[J]. Cancer,1988,61(3):612-617.

[36] Pohl H,Welch HG. The Role of overdiagnosis and reclassification in the marked increase of esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence[J]. Journal of the National Cancer Institute,2005,97(2):142-146.

[37] Shaheen Nicholas,Ransohoff David F. Gastroesophageal reflux,Barrett esophagus,and esophageal cancer:clinical applications[J] .JAMA,2002,287:1982-1986.

[38] Green JA,Amaro R,Barkin JS. REVIEW:Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal Adenocarcinoma[J]. Digestive Diseases and Sciences,2000, 45(12):2367-2368.

[39] Conio M. Long-term endoscopic surveillance of patients with Barrett's esophagus. Incidence of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma:A prospective study[J]. American Journal of Gastroenterology,2003, 98(9):1931-1939.

[40] Thun MJ,Namboodiri MM,Calle EE,et al. Aspirin use and risk of fatal cancer[J].Cancer Res,1993,53:1322-1327.

[41] Giovannucci E,Egan KM,Hunter DJ,et al. Aspirin and the risk of colorectal cancer in women[J]. N Enql J Med, 1995,333(10):609-614.

[42] García Rodríguez,Luis A,Huerta-Alvarez,et al. Reduced risk of colorectal cancer among long-term users of aspirin and nonaspirin nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs[J]. Epidemiology,2001,12(1):88-93.

[43] Collet JP,Sharpe C,Belzile E,et al. Colorectal cancer prevention by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs:effects of dosage and timing[J]. British Journal of Cancer,1999,81(1):62-68.

[44] Jankowski Janusz,Barr Hugh. Improving surveillance for Barrett's oesophagus:AspECT and BOSS trials provide an evidence base[J].BMJ,2006,332:1512.

[45] Vona-Davis L,Riggs DR,Jackson BJ,et al. Anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects of rofecoxib on esophageal cancer in vitro[J]. Journal of Surgical Research,2003,114(2):1.

[46] Katsunobu Oyama,Takashi Fujimura,Itasu Ninomiya,et al. A COX-2 inhibitor prevents the esophageal inflammation-metaplasia-adenocarcinoma sequence in rats[J]. Carcinogenesis,2005,26(3):565-570.

[47] Buttar NS,Wang KK,Anderson MA,et al. The effect of Selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition in barrett's esophagus epithelium:an in vitro study[J]. Journal of the National Cancer Institute,2002,94(6):422-429.

[48] Blain H,Jouzeau JY,Netter P,et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents with selective inhibitory activity on cyclooxygenase-2. Interest and future prospects[J]. La Revue de Médecine Interne,2000,21(11):978-988.

[49] Verburg KM,Maziasz TJ,Weiner E,et al. Cox-2-specific inhibitors:definition of a new therapeutic concept[J].Am J Ther,2001,8:49-64.

[50] Dai Y,Wang WH. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in prevention gastric cancer[J]. World Journal of Gastroenterology,2006,12(18):2884-2889.

[51] Harris R,Beebe-Donk J,Doss H,et al. Aspirin,ibuprofen,and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in cancer prevention:A critical review of non-selective COX-2 blockade(Review)[J]. Oncology Reports,2005,13(4):559-583.

[52] Morgan GP,Williams JG. Inflammatory mediators in the oesophagus[J]. Gut,1994,35(3):297-298.

[53] Wilson KT,Fu S,Ramanujam KS,et al. Increased expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 in Barrett's esophagus and associated adenocarcinomas[J].Cancer Res,1998,58: 2929-2934.

[54] Shirvani VN,Ouatulascar R,Kaur BS,et al. Cyclooxygenase 2 expression in Barrett's esophagus and adenocarcinoma:Exvivo induction by bile salts and acid exposure[J]. Gastroenterology,2000,118(3):487-496.

[55] Tsujii M,Kawano S,Dubois RN. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human colon cancer cslls increases metastatic potential[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America,1997,94(7):3336-3340.

[56] Marrogi AJ,Travis WD,Welsh JA,et al. Nitric oxide synthase,cyclooxygenase 2,and vascular endothelial growth factor in the angiogenesis of non-small cell lung carcinoma[J].Clin Cancer Res,2000,6:4739-4744.

[57] Gately S. The Contributions of Cyclooxygenase-2 to Tumor Angiogenesis[J]. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews,2000, 19(1-2):19-27.

[58] Maley CC. The Combination of Genetic Instability and Clonal Expansion Predicts Progression to Esophageal Adenocarcinoma[J]. Cancer Research,2004,64(20):7629-7633.

[59] Galipeau Patricia C,Li Xiaohong,Blount Patricia L,et al. NSAIDs modulate CDKN2A,TP53, and DNA content risk for progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma[J].PLoS Med,2007,4:e67.

[60] Beales Ian LP,Ogunwobi Olorunseun O. Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 inhibition blocks proliferation and enhances apoptosis in oesophageal adenocarcinoma cells without affecting endothelial prostacyclin production[J].Int J Cancer,2010,126:2247-2255.

[61] Bombardier C. Cardiovascular Risk Associated with Celecoxib in a Clinical Trial for Colorectal Adenoma Prevention[J]. New England Journal of Medicine,2005,352(11):1071-1080.

(收稿日期:2020-02-28)