Hotspot of Adult Cuban Treefrog and Cane Toad Multi-organ Abnormality in Suburban South-west Florida

2020-06-28SharonPrattANZALDUAandJavierGOLDBERG

Sharon Pratt ANZALDUA and Javier GOLDBERG

1 Private University,27427 Horne Ave Bonita Springs,Florida 34135,USA

2 Instituto de Bio y Geociencias del NOA (IBIGEO-CONICET),CCT-Salta,9 de Julio 14,Rosario de Lerma,Salta 4405,Argentina

Abstract This study represents a continuation of the Florida hotspot of tadpole abnormality found in the Southwest Florida suburban roadside drainage ditches in 2012 to determine if the adult frogs and toads frequenting the study sites were anatomically abnormal.The gross examination of all organs included 397 adult anurans and 40 metamorphs representing five anuran species:Osteopilus septentrionalis (N=364), Rhinella marina(N=60),Lithobates sphenocephala (N=7), Anaxyrus terrestris (N=5) and Anaxyrus americanus (N=1). The gonads,liver,kidney and intestines were abnormal at a frequency of 87.4%.The few normal anurans (12.6%) were females and young male adults.We found a significant difference in organ abnormality type and frequency between sexes.Almost all frog and toad males had testicular abnormality (92%) with only 6% with normal testes,whereas the female gonad abnormality was lower,at 41.6%.Hermaphroditism was found in both sexes at a frequency of 26.2%.The toads had a significantly higher frequency of hermaphroditism than the frogs.The toad hermaphroditism frequency was found to be 40%,whereas the frog hermaphroditism 23.3%.A hermaphrodite Cane toad male with a female phenotype coexisted with the normal male phenotype hermaphrodite.The fertility of 27 in situ pairs was assessed.The fertile testicular abnormal male and hermaphrodite pairs produced offspring with abnormal larval morphology.This information adds new evidence of the effect of chemicals on wild populations and the effect on non-target species which has always been underestimated.

Keywords gonad,hermaphrodite,malformation,Osteopilus septentrionalis,Rhinella marina

1.Introduction

Habitat loss,introduction of exotic species,chemicals,increased ultraviolet (UV) radiation,parasites,climate change,and infectious diseases have all been identified as major causes of amphibian decline (Fisheret al.,1996;Daszeket al.,1999;Bradfordet al.,2005).Disease from fungal and viral agents (naturally occurring toxicants) has been proposed as being a leading cause of amphibian decline (Daszaket al.,2003).To strengthen the hypothesis that natural agents,such as Ranavirus,are responsible for the major loss of global amphibian diversity,disease has now been combined with climate change as the agent of mass loss in biodiversity (Priceet al.,2019).

Many researchers still remain uncertain as to the major cause of global amphibian extinction.To answer why amphibians are disappearing,suburban landscapes and identification of hotspots of amphibian abnormalities,are beginning to receive more attention (Ouellet,2000;Lannoo,2008;USFWS,2013;Henleet al.,2017;Haaset al.,2018;Anzaldua Pratt and Goldberg,2019).Most of the studies that have assessed the occurrences of amphibian malformations and mass death in wild populations have been conducted in developed countries(Ouellet,2000;Lannoo,2008).However,studies of hazardous chemicals as a possible agent,other than the agrochemicals (e.g.,Atrazine),are lacking.

As an agent,certain chemicals may be more destructive to amphibian populations because they are artificially administered by humankind in large quantities to large habitat areas and then deliberately reapplied for decades.These chemicals then artificially and unnaturally accumulate in animals and ecosystems in unknown manner.A recent study identified the potential transgenerational impacts of an herbicide (glyphosate in this case) in mammals and suggested ancestral exposures can promote the onset of disease and pathology in subsequent generations (Kubsadet al.,2019).Therefore,insecticide and agrochemical agents,since they can be genotoxic (Sparlinget al.,2015;Lowcocket al.,1997;Boninet al.,1997),causes permanent genetic damage that is transferred to future generations.

Research conducted on the possible effect of agrochemicals,including insecticides,is mandatory to determine if the compound is toxic to nontarget organisms before release for use (i.e.,licensing).Bioassay testing performed by the producing companies can be inadequate in their assessment of chemical toxicity on nontarget organisms (Molanderet al.,2015;Craneet al.,2018;Martinet al.,2019).A Florida joint effort with the U.S.Geological Survey (USGS) studied one species,the Cane toadRhinella marina,in sugar cane fields in South-east Florida,USA (GEER Open File Report 03-54).The USGS/Florida team hypothesized that if atrazine caused gonadal abnormality in anurans,Cane toad populations would show a high incidence of intersex and/or developmental anomalies because Florida uses a large amount of Atrazine on sugarcane.A high percentage of gonadal abnormal toads were collected and findings included a toad intersex abnormality frequency of 39%.Male intersexR.marinatoads were found with female phenotype and testicular abnormality.USGS concluded,like Murphyet al.(2006),that toads inhabiting the agricultural sites applied with atrazine in South-east Florida showed increased incidence of gonadal abnormality/intersex.

The suburban landscape habitats can receive even heavier application of pesticides than agricultural areas since application in suburban USA is governed by the local mosquito control program and based on the eradication of an insect pest for disease control rather than for crop pest eradication (U.S.EPA 2019).The suburban landscape was found to have a higher frequency of frog abnormality than agricultural areas.Murphyet al.(2006) examined the males of three common frog species:the northern green frog (Lithobatesclamitans),the bullfrog(Lithobates catesbeianus),and leopard frog (Lithobates pipiens)inhabiting four landscape types:undeveloped,agricultural,suburban,and urban land cover,and found no significant difference in abnormality prevalence between agricultural and nonagricultural sites.Skellyet al.(2010) sampled the suburban and urban landscape for gonadal abnormality and found 21%gonadal abnormality in the suburban landscape.Anzaldua Pratt and Goldberg (2019) examined the treefrog speciesOsteopilus septentrionalisinhabiting the suburban landscape exposed to insecticides for decades and found 68.8% larval abnormalities,which included the abnormal development of entire organ systems.

Few field studies have been conducted to assess the health of the adult amphibian populations exposed to chemicals by examining the entire gross anatomy of the animal or to examine the possible cumulative effect.McCoyet al.(2008)sampled U.S.populations ofR.marinain agricultural and suburban landscapes and found kidney lesions along with gonadal abnormalities,but with no difference in abnormality frequency between land cover types.Two field studies on treefrog exposure to chemicals have been conducted outside of the USA,one in Italy and the other in India.In Italy,Hyla intermediaexposed to the fungicide pyrimethanil showed malformations in the kidney,liver and gonads (Bernaboet al.,2017).In India,the common species of frog that frequented the research sites,when exposed to agrochemicals and insecticides showed malformation in the gonads,kidney,liver and brain(Hegdeet al.,2019).A brief summary of research performed on the adverse effects of organophosphorus pesticides on the liver showed that organophosphorus pesticides damages the liver and is a hepatoxin (Karami-Mohajeriet al.,2017).In Europe,interest has increased in endocrine-disrupting chemicals and numerous studies have been published on methodology to diagnose and monitor water quality for endocrine reducing chemicals which includes monitoring of natural populations and use of bioassays to diagnose exposure (Bracket al.,2019).However,studies are lacking on organ abnormality in anuran field populations other than that of the endocrine system.

This study represents a continuation of a study of an abnormal larval frog population located in a suburban USA landscape that had received the heavy application of mosquito control insecticides for years (Anzaldua Pratt and Goldberg,2019).The study became a seven year project (2012-2018)of the anuran abnormality hotspot with a new description of adult anuran multi-organ abnormality,representing an addition to the originalO.septentrionalistadpole abnormality description (Anzaldua Pratt and Goldberg,2019).The objective of the present study was to continue studying the abnormal populations by assessing:(1) the adult organ malformation,(2) if malformation occurred in other sympatric anuran species,(3) if differences exist between sexes in the incidence of malformations,and (4) experimentally,if the gonadal malformation has an impact on progeny.

2.Material and Methods

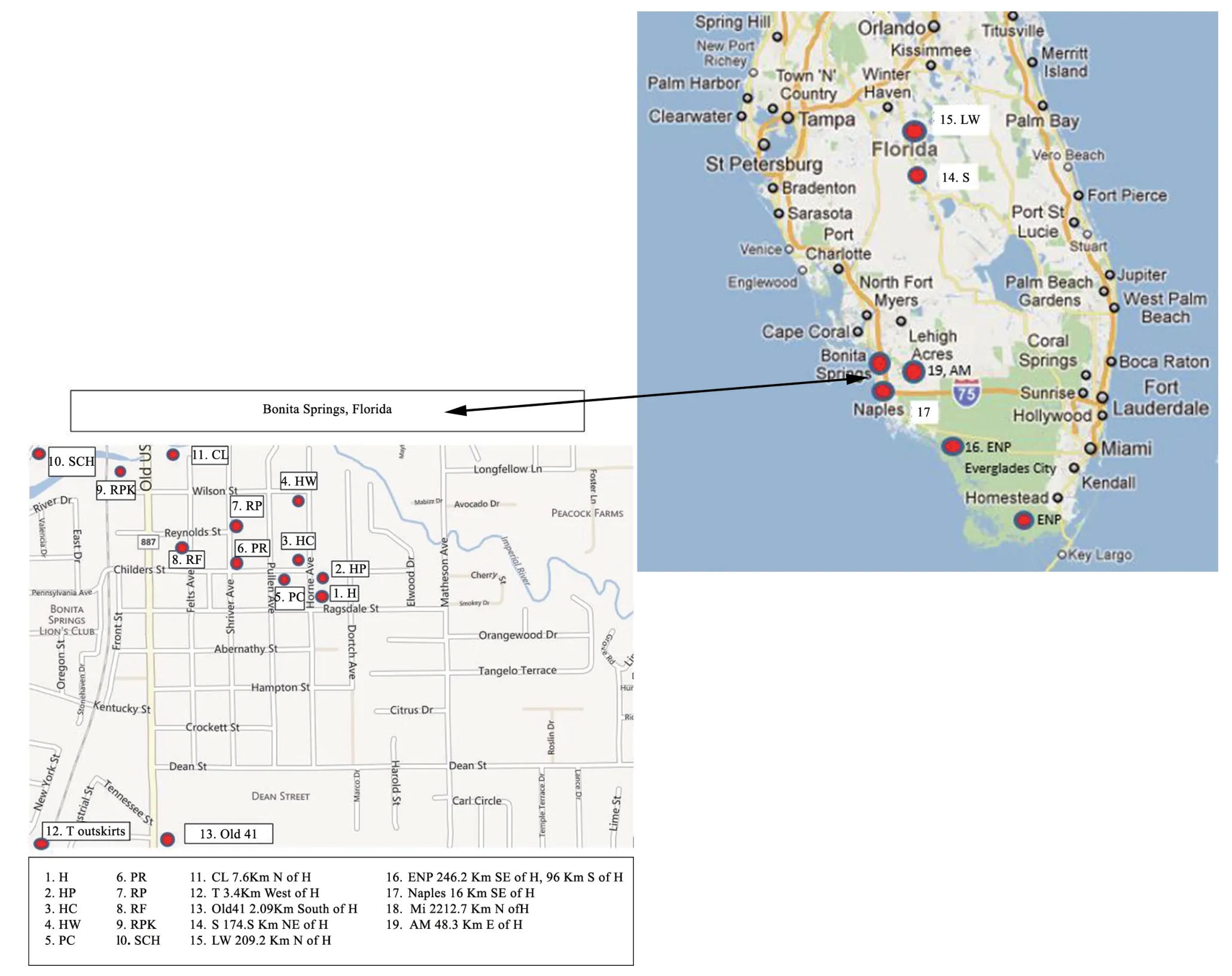

2.1.Sample collectionAdult and metamorph anuran specimens (N=397) ofOsteopilus septentrionalis,Rhinella marina,Lithobates sphenocephalus,Anaxyrus terrestris,andA.americanus(out-of-state) were collected in the suburban South-west Florida study sites previously described in Anzaldua Pratt and Goldberg (2019) with additional study sites added in 2016-2018(Figure 1).The new sites added to the project were:(1) additional sites within the suburban neighborhood;(2) Sebring,Florida sites (174.5 km north-east of the previous study sites);(3) one outof-state site (not planned sample) in suburban mid-Michigan(A.americanus2 212.7 km north of the previous study sites);and(4) Lake Wales,Florida (209.2 km north).The additional sites added in 2016-2018 all containedO.septentrionalis,but did not always contain the other four anuran species.Three types of sites were found in the suburban area of Southwestern Florida:The first were ephemeral insecticide treated roadside drainage ditches (Figure 2A),lining the streets averaging 1.83 m × 1.22 m with a 254 mm maximum rainwater depth at mid-pool.They were treated continually with insecticide.The second type were the artificial pond (Figure 2B),which were untreated with insecticide and a permanent body of water filled with rainwater.The dimensions for this pond were 3.05 m × 4.57 m with a depth of 1.22 m.The third type were the“H yard”container sites (Figure 2C),which were untreated outdoor empty plastic containers naturally-filled with rainwater and then left undisturbed.These containers held an average maximum of four liters.The control site types U.S.Wildlife Refuges in Everglades National Park (Figure 2D) and Golden Gate Naples rural in non spray insecticidal zones were ephemeral puddles of rainwater similar in size and site longevity to suburban sites.

Figure 1 Map of Florida,USA.Normal view of Florida State map with a zoom of Bonita Springs to depict suburban field sites.The red circles indicate field study site locations.The red circles indicate single field study site locations with the exception of the ENP(site 16) includes the Homestead and Everglades City sites.Naples had two site locations one in AM (site 19) located in Golden Gate,Naples,FL and the Naples (site 17) located in suburban,Naples,FL.Site 18 corresponds to the Michigan site and it is not depicted in this figure.

Figure 2 Field study sites.The four field study types.(A) treated ephemeral roadside drainage ditch pool.(B) untreated permanent Horne pool (HP).(C) untreated yard containers.(D) untreated ephemeral pool in Everglades National Park (ENP).

2.2.Gross examination and data analysisThe gross examinations occurred from 2013 to 2018.The majority of examinations occurred between the field seasons 2016 to 2018 because the organ abnormality was recognized in 2016.The data were organized by date of dissection,which immediately followed the sampling date.Each dissection was performed after euthanisation following international ethical procedure published online for invasive species (Johnson,2013).The majority of the dissections were completed on the day of the field collection or within 2 days following the field collection date to eliminate a need for specimen housing and to promote each gross examination to be a true representation of the health condition of the animals in the field site at the time of collection.A total of 91animals (40 metamorphs,reared;51 adults,in situ housed for more than 2 days before necropsy)that were not fresh field-collected dissections.Those specimens were reared and then dissected.Each dissected animal was carefully photographed live,upon collection date;then,at the dissection,photographs were taken within its collection group,then individually.Seeing animals lined up in their group during dissection was critical for observing the organ at different states of abnormality,which assisted in diagnosis.Another key method,in diagnosis was that only the unpreserved specimens were used because the true color of each abnormal organ was necessary for an accurate diagnosis of organ abnormality.All organ abnormalities counted were in a pronounced stage of necrosis.The testicular abnormality described as asymmetrical size had to be more than a 15% discrepancy between the paired gonads.The frequency of multi-organ abnormality found in all anuran species was calculated by the total number of abnormal frogs and toads collected divided by the total number of frogs and toads collected (abnormal plus normal).Another calculation was performed to determine if the toad family(Bufonidae:R.marina,A.terrestris,andA.americanus) displayed a difference in organ abnormality type and frequency (indicating vulnerability or resistance to the pollutant) compared with the frog families (Hylidae and Ranidae:O.septentrionalis,L.sphenocephalus).Finally,a more detailed calculation for each of the individual species was completed.Incidence levels among sexes and species were compared with a homogeneity Chisquare test following Barcenas-Ibarraet al.(2015).Of the 5 anuran species,we dissected 397 individuals including those that were reared or in situ housed before dissection.We dissected a total of 232 males (M),125 females (F),and total 40 metamorphs of all 5 species.The total number of specimens collected was 324 (190 M,94 F,and 40 metamorphs) forO.septentrionalis;60(34 M,26 F) forR.marina;7 (4 M,3 F) forL.sphenocephalus;5(3 M,2 F) forA.terrestris;and 1 M forA.americanus.We used the terminology reported by Heckeret al.(2006) to describe all gonadal abnormalities.Sex in the hermaphrodite frog or toad was identified through the presence of secondary sexual characteristics (vocal sacs,different body lengths,toad skin pattern,frog nuptial pads).MaleA.terrestristoads have a dark throat pigmentation that is lacking in females.R.marinafemales have a specific dorsal pattern and are usually larger (depending on the age) than the male.The maleR.marinalacks a pattern.TheR.marinamale hermaphrodite toad had a female pattern.In those cases where the hermaphrodite male toadR.marinahad an external female morphology,but had sex reversal gonads,we considered the behavior of the toad to determine the original sex,i.e.,the male toad with the female external morphology engaged in amplexus in the male position.Diagnosis was achieved via gross examination and/or by a stereo dissection microscope for gonad confirmation identification in the metamorph less than 28 mm in size.Microscopic examination was also used for some ovarian ova and intestinal polyps large enough to view with the naked eye,but requiring confirmation of diagnosis with magnification.We used a P510 Nikon digital camera with automatic date,time,and geographic positioning system (GPS) recorded data.Four dissected frogs (3 metamorphs,1 adult) from the Everglades National Park (Study# EVER-00493) were returned to the park which are archived at the South Florida Collections Management Center (FL,USA).

2.3.Gonadal function experimentsThe gonadal function experiments involved mating experiments.We studied a total of 27 pairs ofO.septentrionalis.All 27 frog pairs were collected from insecticide treated sites.All frog pairs were considered in situ because they were all collected from the field sites.The laid eggs and offspring were considered ex situ because they were reared.Adults were dissected immediately after eggs were laid.The pairs in amplexus in the field sites were carefully placed into a tank of spring water or habitat water to lay their clutch.Each of the 27 clutches studied were maintained outdoors in glass terrariums receiving natural sunlight.The ex-situ clutches laid by the in-situ pairs received water changes every third day and were fed spinach every day or second day.The reared progeny (metamorphs and adultsN=91) were maintained indoors housed in plastic 3.78 L screw cap containers receiving natural light and fed crickets dusted with Rep-Cal phosphorusfree VitD3 powder (every third feeding) before dissection.

3.Results

Necropsy results were combined for all sites because there was no difference in frequency of abnormal frogs/toads (shown statistically) between treated and untreated sites and the control sites (AM,ENP) sampling were too small to differentiate from the non control sites.

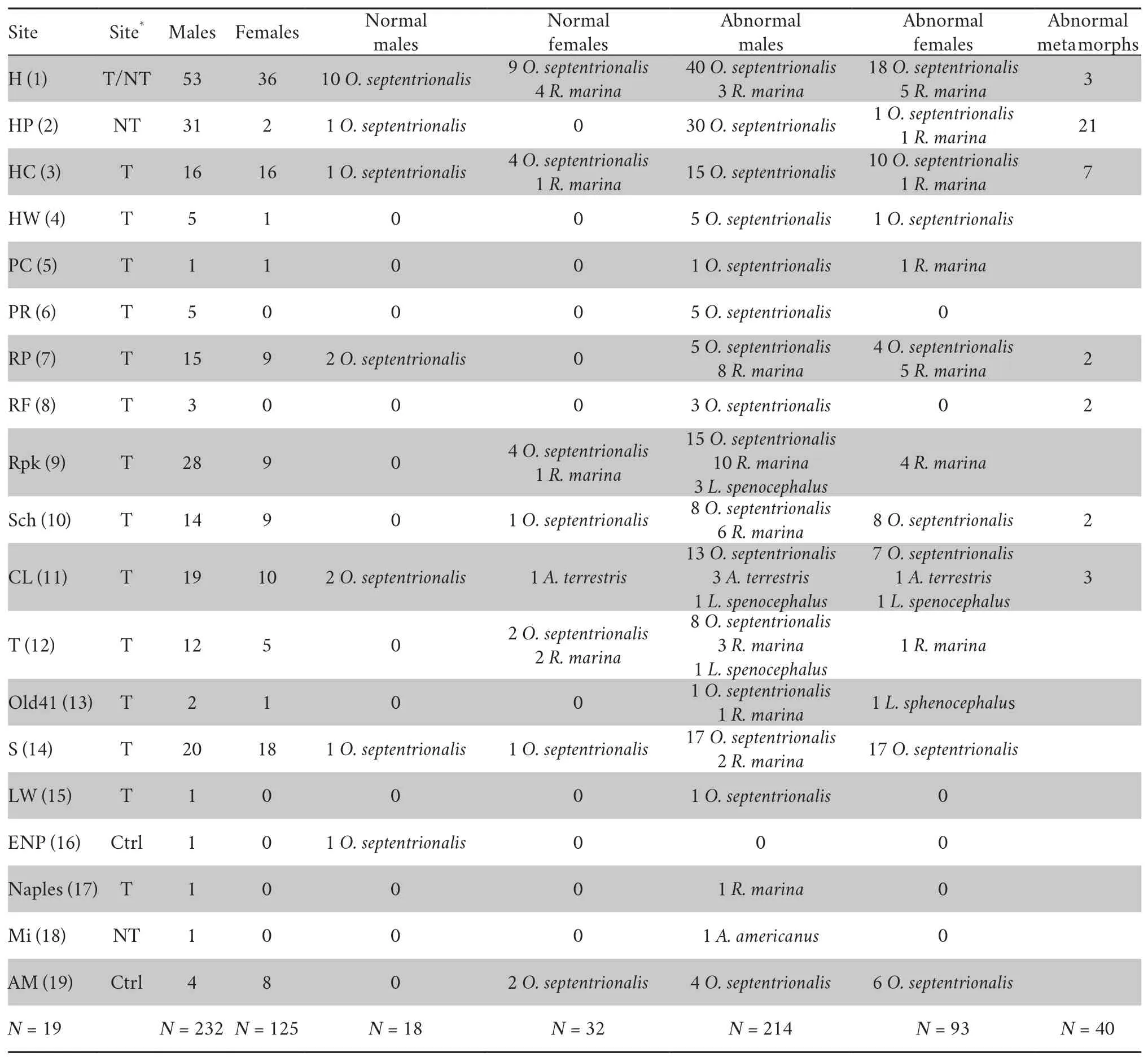

3.1.Multi-organ abnormalityThe organ type abnormality frequency for all 397 individuals (M and F) anurans was 87.4%(347/397).The frequency of individuals with normal organ was 12.6% (50/397).Within the females,25.6% (32/125) had normal anatomy and 74.4% (93/125) showed some kind of abnormality.We found 41.6% (52/125) gonadal abnormal females (abnormal eggs in ovaries).Only 6% (14/232) of males had normal testes which is a 92% frequency of gonadal abnormality in the males(214/232).A total of 7.8% (18/232) of males had normal testes and normal non-reproductive organs.Malformation levels for both sexes in the whole sample were significantly higher than expected by chance (χ2=11.48;d.f.=1;P=0.0007),with males showing higher incidence.The proportion of specimens with some kind of malformation (Table 1) always exceeded 75% of specimens in each site.

We recorded a high frequency,87.4%,of organ abnormality in all 5 species (Figure 3).When we analyzed the total sum of all individuals,including adults and metamorphs,we found that,in most cases,abnormalities occurred in several organs simultaneously.Higher incidence of abnormalities was found in the gonads,but also in the small intestine,kidney,liver,and gall bladder (Figures 3 and 4).We also found small intestines with polyps (Figure 3A),and multiple organ system dysfunction(MODS;Figure 3B).The incidence of malformed frog and toad organ abnormality was significantly different among species (χ2=161.63;d.f.=3;P< 0.0001).In each of the five individual species,organ abnormality was:88.9% (288/324) forO.septentrionalis,100%,(7/7) forL.sphenocephalus,76.7% (46/60)forR.marina,20% (1/5) forA.terrestris(1/5),and 100% (1/1) forA.americanus.Strikingly,in only 50 (both sexes) of the 397 anurans sampled(12.6%) were all organs normal (Figure 3D),which were females(32/50) and young males (18/50).Between species,generally,all five species had the same multi-organ abnormality types with the males almost all having testicular abnormalities.

The intestine malformation frequency was 30.2% (120/397)(total sum all individuals) and involved ruptures and leaking tissue (Figure 3F).The intestinal tissue was found to be more often discolored red-orange,disintegrating and 8.8% (35/397) of specimens had numerous polyps (Figure 3A).Toads had more often red-orange intestinal polyps (Figure 3A left).The kidney and liver abnormalities were mostly found together with the organs disintegrating (Figure 3E,I).Both sexes had identical liver abnormality frequencies:17.7% for both males (41/232) and females (22/125).We observed a difference in liver abnormality type between the frogs and toads.The frog liver stayed black and would disintegrate with the exception of one female frog that had a yellow liver (Figure 4B).The toad liver changedcolor.The liver in the female and intersex maleR.marinatoads turned from normal black to bright red with or without pale white liver cells (Figure 3E,Figure 4A).The kidneys,normally red,were found blackened and disintegrating (Figure 3I).Both liver and kidney filled the body cavity with black fluid (Figure 3B,E,I).The nearby organs,testes and intestines,displayed black patches with signs of MODS (Figure 3F).Some specimens were found with the entire body cavity mushed with disintegrating organs (MODS) (Figure 3B).The gall bladder appeared enlarged(Figure 3C).

Table 1 Data of 19 field site anuran collections.Separate data for each site species,gender,normal,and abnormality count are provided (reared metamorphs of O.septentrionalis included).The site number is provided (between brackets) as it appears in Figure 1.

3.2.Ovarian and testicular abnormalityWe observed a difference in organ abnormality prevalence between sexes in the overall populations.The gonadal abnormality in the males occurred in the testes whereas in the female,it occurred in the ovaries (Figure 3G).So,no malformation was observed in accessory ducts.The female gonadal abnormality prevalence for all five species under study was 41.6% (52/125).The female ovaries contained abnormal eggs.The retained eggs inside the ovary were not uniform in size and the shape was often irregular.Upon microscopic examination,the retained eggs often were empty shells of cytoplasm (Figure 3H).

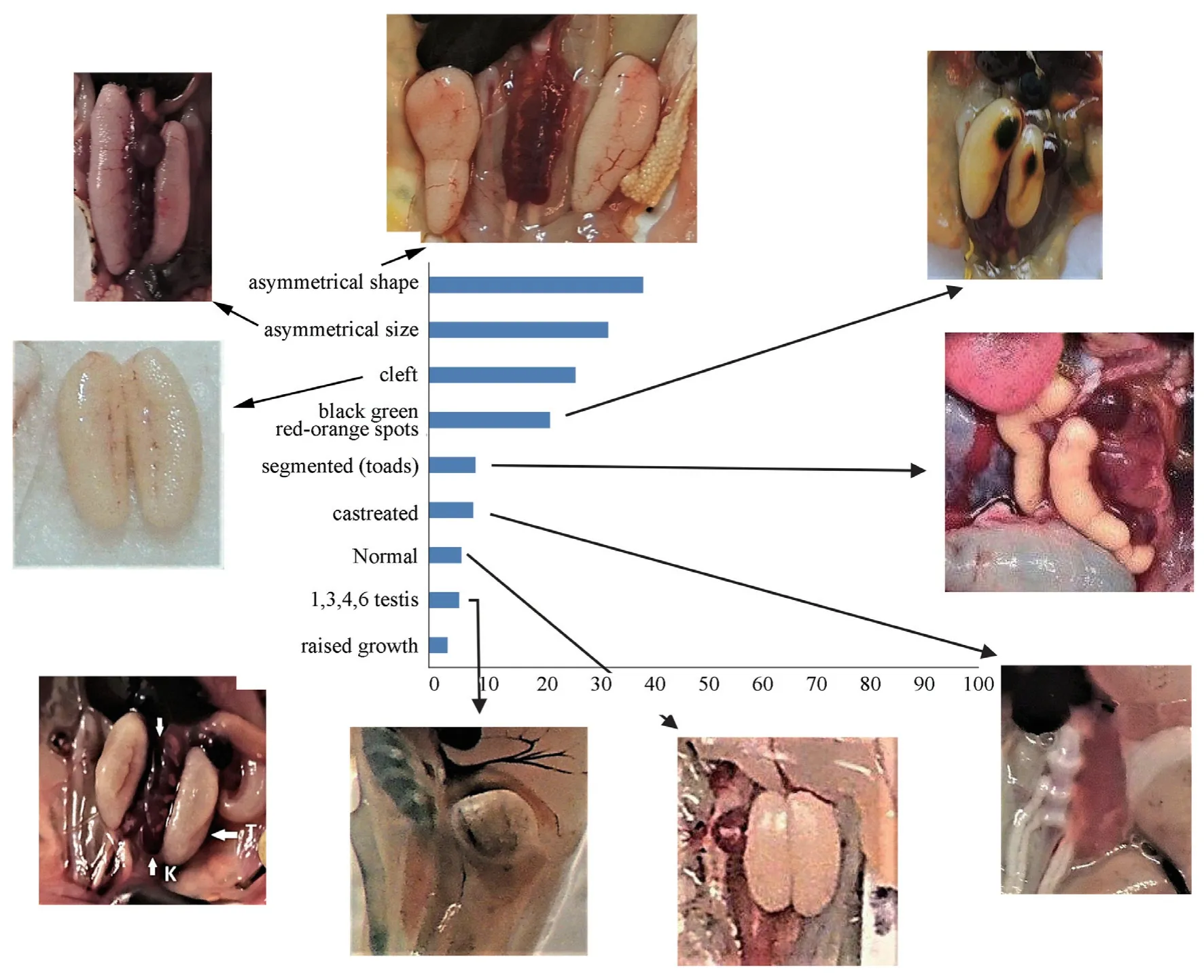

Figure 3 Percentages of each organ abnormality type.(A) Intestinal polyps (white arrow) toad (left),frog (right).(B) Multiple Organ System Dysfunction (MODS) frog.(C) Gall bladder abnormality.(D) Normal Rhinella marina female (far left),normal female Osteopilus septentrionalis (far right),normal male O.septentrionalis (middle).(E) Liver abnormality frog (left),toad (right).(F) Intestinal abnormality.(G) Gonadal (white arrow) abnormality in the female (far right and left) and male (middle).(H) 20× close-up of abnormal eggs in female ovary pictured in (G).(I) Kidney abnormality.GB:gall bladder;I:intestine;K:kidney;L:liver;S:stomach;T:testis.The dissection and animal numbers are included in the photographs.

The male testicular abnormality prevalence for all five species under study was 92% (214/232) (Figure 5).Age-related difference were found to affect testicular abnormality in the males because the few normal gonad adult males (6%,14/232)were young males.Eight anuran testicular abnormality types were found alone or in combination (Figure 5):asymmetrical shape;asymmetrical size greater than 15%;cleft;areas of discoloration black,green,red-orange spots;segmented;curled (toads);castrated;1,3,4,6 testis in one individual;and an abnormal mass that rose out from the lining of the organ.Every individual male frog or toad had its own testicular abnormality type combination even within one site location implying many of the same age and/or from the same clutch had different testicular abnormalities.We seldom found two frogs with the identical testicular abnormality type combination in any given field sampling site and date for all 6 years sampled at all sites.Three testicular abnormalities,asymmetrical shape,asymmetrical size,and cleft,were the most frequent frog testicular abnormalities and were closest in frequency because those three abnormalities occurred in combination.The abnormal toad testes were segmented and often curled with asymmetrical shape and size.The testes also appeared discontinuous in different masses.The abnormal toad testes did not have the frog testicular abnormalities:cleft,raised growth or castration.

Figure 4 Rhinella marina and Osteopilus septentrionalis liver abnormalities.(A) A both sex (in dorsal and ventral view) R.marina (numbered from left to right) toads dissection:toad 1 female with red liver abnormality,toad 3 female liver beginning to turn color,male toads 2,4,and 5 with black livers.(B) O.septentrionalis yellow female (below,dorsal view) with liver abnormality (above).

3.3.Hermaphroditism in frogs and toadsThe frequency of hermaphroditism in the five frog and toad species was 26.2%(104/397).In males,the frequency was 40.1% (93/232) and 8.8%(11/125) in females.The male and female hermaphrodite frogs all had an ordinary phenotype that did not reveal their mixed sex anatomy.They behaved as usual for the sex,i.e.,they all amplexed in the correct positions andO.septentrionalisturned yellow (Figure 6A,B).The hermaphrodite male toadA.terrestrisalso,like the frogs,had the ordinary appearance for the sex.The maleR.marinahermaphrodite toad was the only species found that did not have the typical sex phenotype.In numerous sites,the male hermaphroditeR.marinawith a female phenotype(i.e.,dorsal skin pattern) appeared and intermingled with the male phenotype (i.e.,without a dorsal skin pattern with vocal sacs).In the field sites we found 45.8% (11/24) ofR.marinamale hermaphrodite toads had female morphology (Figure 7A,B,D,E) and 54.2% (13/24) had the male phenotype morphology(Figure 4A,Figure 7C).The male hermaphrodite toads with the female external morphology were observed to behave and function as a male with demonstration of amplexus in the correct position with the opposite sex (Figure 7A,B).

The frequency of hermaphroditism in the two species of frogs was 23.3% (77/331) and the condition was found in both sex,however the female condition occurred far less frequently than the male condition.Sex reversal inO.septentrionaliswas 22.2% (72/324),with a male hermaphroditism frog frequency of 32.1% (61/190),and female frequency of 11.7% (11/94).The hermaphroditism inL.sphenocephaluswas higher,although we found fewer specimens of this species.The hermaphroditism frequency forL.sphenocephaluswas 71.4% (5/7),with 100% (5/5)male hermaphrodite frogs.

Frog hermaphroditism was identified by the presence of an ovotestis (Figure 6C-E).Ovotestis is defined as frog or toad gonadal tissue that is more than 30% female (Heckeret al.,2006).All male hermaphrodite frogs had this extra organ (Figure 6D,E),the females also had an ovotestis that resembled the male tubular ovotestis where the oviduct was coiled (Figure 6C).Some ovotestis morphological variation dependent on the individual and age of the animal was observed.Commonly,ovotestis appeared as a separate organ (Figure 6D),however,in the males,it might grow from the anterior tip of each testis(Figure 6E).

Ovotestis was also found in the young metamorph and in the three-month-male.The ovotestis in the younger hermaphrodite male was a smaller and more delicate version of the adult organ.The color of the ovotestis was more often the typical gonad color and located anterior of the kidney.The fat body was bright orange (Figure 6F).In the older male the ovotestis tubular mass filled the entire lower body cavity masking all other organs from view with its profuse growth(Figure 6D,E).Eggs were found in the ovotestis and ovaries inO.septentrionalisfor both sex.The frequency of hermaphrodite frogs with eggs was 18.1% (13/72).

Figure 5 Percentages of each of the eight male testicular abnormality types with arrows indicating each abnormality:asymmetrical shape,asymmetrical size,cleft,black,green,red-orange spots,segmented (only toads),castrated,normal,1,3,4,6 testis,and raised growth.K:kidney;T:testis.

Hermaphroditism was only found in the male toad.In both toad species,the hermaphroditism frequency (both sex) was 40% (26/65).The frequency ofR.marinahermaphroditism in males was that of 70.6 % (24/34 males) and the frequency of the male hermaphroditism inA.terrestrismales was 66.7% (2/3 males).R.marinadisplayed two types of hermaphrodite male phenotypes:(1) female morphology (Figure 7A,D,E),and (2)male morphology (Figure 4A,Figure 7C).The frequency of the male hermaphrodite morphology (i.e.without a pattern,vocal sacs) was 54.2% (13/24).The frequency of the female phenotype(i.e.,with a pattern) male hermaphrodite frequency was 45.8%(11/24).The two types of hermaphrodite phenotypes were found at all sites and both types of hermaphrodite phenotypes carrying eggs and oocytes had a frequency of 70.8% (17/24).

3.4.FertilityWe used 27O.septentrionalisin situ pairs in the fertility experiment and all paired males were 100% testicular abnormal.There were 29.63% (8/27) pairs that were both male and female hermaphrodites and 38.89% (22/54) pairs with only one of the two individuals in the pair being a hermaphrodite.All pairs laid eggs.Each male had its own testicular abnormality,yet were still 100% fertile (Figure 8,Figure 9,Figure 10).The offspring for all 27 pairs had all similar embryonic and larval abnormalities with mass death and low survival to metamorphosis (Anzaldua Pratt and Goldberg,2019).The highest survival to metamorphosis of progeny was 10.54%,but clutches had a 4.89% chance of survival to metamorphosis on average (Figure 8,Figure 9,Figure 10).The offspring from pairs with the hermaphrodite condition had the same abnormality types and low survival as the pairs with only testicular abnormality.

A major and highly frequent,abnormality in offspring was growth retardation.The small percentage of larvae that did not experience growth retardation and grew to a normal size as tadpoles,but ceased to grow as metamorphs.Most of the metamorphs never achieved adulthood and perished within four weeks.The small percentage of metamorphs that did succeed to survive to adulthood took 1.5 years to reach the minimum sexual maturity size.This process normally takes three months for males and eight months for females (Anzaldua pers.obs.).

Figure 6 Female and male frog hermaphroditism in the frog Osteopilus septentrionalis.(A) Amplexus male and female hermaphrodite pair at field site.(B) Gross examination (left) of the amplexus hermaphrodite pair from the field site pictured in (A) showing female with five testis,male with three testis (one bulb testis),with a close up of the five bulbous testis in the female (right).(C) Gross examination of a female hermaphrodite with ovotestis (OT),oviducts (OV),and abnormal eggs.(D) Gross examination of a male hermaphrodite with cleft testes (T) and ovotestis.(E) Gross examination of a male hermaphrodite with ovotestis growing from the anterior tip of each cleft testis.(F) Non-hermaphrodite male with asymmetrical size testis and orange fat bodies (FB).

No male parent testicular abnormality was directly accountable for any given embryonic or larval abnormality.For example,tadpoles with scoliosis were produced by 22.22%(6/27) of normal external morphology parent pairs.In one case,in Pair 2 2016 (Figure 8),the male had the testicular abnormality combination of discolored brown testes with asymmetrical size.In another case Pair 1 2017 (Figure 9) the male had simply a cleft testis.Pair 3 2018 (Figure 10) with a hermaphrodite male and female also produced progeny with scoliosis.The severity of the abnormality could be related to males with discolored green testes (Figure 5),or when both parents were hermaphrodites.In those cases,when the male parent had one of those two types of abnormality types,the offspring displayed particularly severely misshapen embryonic malformation.

Figure 7 Male toad hermaphroditism in Rhinella marina.(A) In situ amplexus hermaphrodite male with female phenotype (top) with a female (bottom).(B) Gross examination of the amplexus pair in (A) showing the male hermaphrodite (right) with abnormal curled,and segmented testis pair and the female (left).Detail (left) showing the female abnormal egg clutch (ovary discolored,eggs abnormal).(C-E) Dorsal and gross examination of hermaphrodite specimens.(C) Male hermaphrodite normal phenotype (solid) with four testis (T) and an ovary (O) with oocytes.(D) Male hermaphrodite female phenotype (pattern) with red-liver and asymmetrical,curled,and segmented testis pair (T).(E) Male hermaphrodite female phenotype (pattern) with curled testis pair.

4.Discussion

The insecticide applied for mosquito control to the anuran breeding pool is suggested as the most probable endocrine disrupting chemical inducing the numerous anuran abnormalities described,simply because the temporary pool of water in which the anuran bred every year is rainwater with added insecticide without runoff.At the time of the field collections,the presence of larvicide insecticide in the water was very visible.The water was discolored,smelled of the chemical,and had a thick oil surface film (Anzaldua Pratt and Goldberg,2019).Other chemicals may have been present in the water and a continued analysis (e.g.bioassay,water chemistry) is required to conclude the agent cause-effect relationship.

Figure 8 Fertility experiment 2016.Bar chart of each pair male testicular abnormality gonad morphology with corresponding offspring clutch percentage of survival to metamorphosis.The date the clutch was laid in 2016 is provided for each individual pair.

The types of anuran multi-organ abnormalities observed here are the known abnormal morphologies induced by an endocrine disrupting chemical agent environmental toxicant.The endocrine disruptor chemical interferes with specific hormonal signaling and,after fetal or postnatal exposure,promotes disease states in the adult (Foranet al.,2002;Heindallet al.,2005).Scientific research has shown that 90% of the reported effects of endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDC) on aquatic animals can be associated with interference in sexual differentiation,infertility,and reduction in sperm production(da Silvaet al.,2018).The published main effects caused by EDCs on amphibians include:altered hormonal activity during embryonic development (11%),changes in anatomy (33%) and behavior (11%),reduction in reproductive success (11%),as well as gonadal abnormalities (22%),hermaphroditism (33%),and other alterations of the reproductive system (45%) (da Silvaet al.,2018).All the listed published EDC-induced larval and adult multi-organ abnormalities match the abnormality types found in suburban South-west Florida larvae and adults.The most frequent abnormality type found in other investigations is reproductive system alteration (45%),which matches our findings.In the literature,the second most common abnormality reported is anatomical malformation (da Silvaet al.,2018).Again,our findings agree with the literature because we also found that the changes in anatomy were the second most frequent abnormality type induced by the endocrine-reducing chemical.We found that the second highest abnormalities were those in the intestines,kidney and liver.

The 92% testicular abnormality frequency found in the South-west Florida suburban study sites was very high,affecting almost 100% of the male population.The one testicular abnormal (three testis) toad found from suburban mid-Michigan USA,thousands of kilometers away from the Southwest Florida site,may indicate that testicular abnormality may be a high frequency abnormality elsewhere.This high frequency percentage of abnormal testes might be an indication that malformations may occur under normal conditions(Goldberg 2013,2015),but the high percentage observed in our main study sites suggests they are all somehow being exposed to the same chemical or chemicals and similarly respond to the chemical contaminant,perhaps,via a decrease in the production of the male hormone androgen (Babic-Gojmeracet al.,1989;Kniewaldet al.,2000;Hayeset al.,2006).

Figure 9 Fertility experiment 2017.Bar chart of each pair male testicular abnormality gonad morphology with corresponding offspring clutch percentage of survival to metamorphosis.The dotted line indicates to adult morphology with the corresponding percentage.The date the clutch was laid in 2017 is provided for each individual pair.

Sex reversal condition was also frequently observed.Hermaphroditism occurs when the abnormal male not only produces less androgen (demasculinization),but also synthesizes the female hormone estrogen (feminization) which causes the animal to feminize (Carret al.,2003;Hayeset al.,2006).Hermaphroditism has also been reported in another USA suburban survey study,with a high frequency (Skellyet al.,2010).We found high frequencies of testicular and hermaphrodite gonadal abnormalities.For frog populations ofPelophylax esculentusin suburban (city) and forest landscapes located in in Russia,Belarus,Ukraine and Moldova,Litvinchuk(2018) showed a 61% frequency of testicular abnormality.Many of the testicular abnormality types found in Russia were similar to those identified in South-west Florida,USA:testicular asymmetry,abnormal shape,black areas,and cysts.In field studies,Hayeset al.(2002,2003) likewise found testicular abnormality and hermaphroditism.They sampled field populations of youngLithobates pipiensexposed to atrazine in agricultural landscapes located across eight mid-west U.S.sites and found under-developed testes in 36% of the cases and hermaphrodites in 29%.Carret al.(2003) found a certain correlation between malformations and a high concentration of herbicide.

A testicular abnormal male can successfully fertilize clutches of eggs,as shown in the fertility experiment where 27 in situ males with testicular abnormalities successfully fertilized each clutch.Fertilization is not a problem.The fertilized eggs appeared abnormal as the egg developed.The offspring of every testicular abnormal male parent developed all of the field abnormalities with mass death of the clutch,as previously described (Anzaldua Pratt and Goldberg,2019).Thus,the field collected testicular abnormal male in this study could be positively linked with producing offspring with identical abnormal morphology found in the field (Anzaldua Pratt and Goldberg,2019).

Figure 10 Fertility experiment 2018.Bar chart of each pair male testicular abnormality gonad morphology with corresponding offspring clutch percentage of survival to metamorphosis.The date the clutch was laid in 2018 is provided for each individual pair.

Endocrine disrupting chemicals demonstra ted transgenerational transfer of the abnormal condition (Anwayet al.,2006;Kubsadet al.,2019).We showed that abnormal parents produced abnormal offspring consecutively in field seasons (2016-2018).In the field sites the testicular abnormal males appear to fertilize eggs,the eggs hatch,but then larvae are almost all abnormal.The question is why do we see surviving adults today at the field sites with such high percentiles of such severe larval (68.8%) (Anzaldua Pratt and Goldberg,2019) and adult (87.4%) abnormalities.Since there were considerably more normal females than males found,out of 50 total normal anurans (males plus females) (12.6% of 397),32 (32/50) were female and only 18 (18/50) were males,the females must be contributing enough good health (i.e.,some survival to metamorphosis,4.89%,in the fertility experiment)to each mating to produce a next generation,even if the next generation is functionally disabled.A continued field population analysis,with marked adults,analyzing reproductive success,age,longevity,and migration,etc.will help to answer this question.

Endocrine disruptor interferes with specific hormonal signaling and,after fetal or postnatal exposure,promotes disease states in the adult (Foranet al.,2002;Heindallet al,2005).The disease state MODS in the adult described in this study may be caused by the intestine rupture and leakage of contents into the peritoneal cavity which,then,caused the other organs to systematically shut down (blackened liver,blackened kidney,and blackened testes areas).This seems to be a replay of the larval MODS occurring in the adult (Anzaldua Pratt and Goldberg,2019).Another phenomenon occurring in the adult organ system is the appearance of the red liver abnormality in theR.marinafemale and hermaphrodite male toads.The sexrestricted liver abnormality totals also identified sex-restricted abnormalities occurring in two different organ systems:the reproductive (testicular and sex reversal abnormalities) and the digestive (liver abnormality) systems.

If a gross examination is not performed in a biodiversity field survey,abnormality might not be found considering the anurans appeared externally normal (except for the hermaphroditeRhinella marinatoads),but were anatomically abnormal.A biodiversity anuran survey method should include a gross examination of the anuran to find hotspots of anatomic abnormality like this one.In anurans,most descriptions of malformations in gonads refer to experimental results (and debate exists about the actual effect of the applied chemicals)but some studies report cases in wild species.Therefore,studies are needed in natural environmental conditions,and in different environments to expand our knowledge about the occurrence of abnormalities in wild populations that can serve as reference scenarios for the evaluation of the possible effects of exposure to synthetic chemical compounds.

AcknowledgementsWe thank J.HARDING for suggestions and encouragement.S.ANZALDUA thanks L.ANZALDUA for funding and support.A special thanks to K.HENLE for his critical review.We thank D.CRILLEY who provided Adobe Photoshop technical support.We thank the National Park Service,Everglades National Park,South Florida Collection Management Center for research project and protocol permission and access to the National Park research sites.Permit# EVER-2013-SCI-0021,EVER2014-SCI-0019 Study# EVER-00493.

杂志排行

Asian Herpetological Research的其它文章

- The Effects of Prey Items Diversity and Digestible Materials in Stomach on Digestive Tract Length in Hylarana guentheri

- Distribution Changes of Chinese Skink (Eumeces chinensis) in China:the Impacts of Global Climate Change

- Effects of Acute Temperature Stress on mRNA Expression of Transferrin in the Yellow Pond Turtle Mauremys mutica

- Behavior and Approximate Entropy of Right-eye Lateralization During Predation in the Music Frog

- Ring Clinal Variation in Morphology of the Green Odorous Frog (Odorrana margaretae)

- A New Species of the Genus Rhabdophis Fitzinger,1843 (Squamata:Colubridae)in Southwestern Sichuan,China