Impact of primary tumour location on colorectal liver metastases: A systematic review

2020-06-19GeorgeBinghamAlyshaShetyeReenaSureshRezaMirnezami

George Bingham, Alysha Shetye, Reena Suresh, Reza Mirnezami

Abstract

Key words: Liver metastasis; Colorectal cancer; Location; Primary tumour; Outcome

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer subtype world-wide with over 1 million new cases diagnosed in 2018[1]. Metastatic disease represents the primary cause of mortality in CRC, and up to 25% of patients are found to have synchronous metastases at the time of diagnosis. A further 40% will develop metachronous disease and approximately 25%-30% of patients will develop liver metastases in the course of follow-up[2]. Indications for curative intent treatment of CRC liver metastases (CRCLM) have expanded rapidly over the last three decades,and several key factors have led to improvements in outcome, notably enhanced radiological detection, improved chemotherapeutic efficacy and more aggressive surgical treatment[3]. With modern combined-modality treatment approaches, 5-year survival in excess of 50% has been reported in selected patients with CRCLM[4].Clinico-pathological factors believed to be associated with worse oncological outcome in CRCLM include the presence of synchronous metastases, bi-lobar liver involvement, metastases > 5 cm in size, and the presence of extra-hepatic disease[4,5]. It has also been suggested by a number of authors that primary tumour location (PTL) -right side versus left side, can influence patterns of hepatic metastatic dissemination and survival[6,7]. For example, a number of studies have demonstrated inferior oncological outcome in patients undergoing surgical resection of CRCLM with rightsided versus left-sided colonic primary tumours[8-10]. This has not been a consistent observation, and others have shown no clear association[11,12]. The aim of the present systematic review is to provide a summary of the available evidence on the impact of PTL on oncological outcomes in patients with CRCLM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Identification of studies

An electronic literature search was carried out using MEDLINE (1965 to March 2020),EMBASE (1980 to March 2020) and the Cochrane Library databases. The medical subject heading terms and key words used are as follows: “Colon” or “rectal cancer”,“liver metastasis” or “liver metastases” or “hepatic metastasis” or “hepatic metastases” and “left” and “Right”. Studies, abstracts and citations were scanned for relevance. The latest date of this search was 27 March 2020. The publications deemed relevant were read in full and assessed for inclusion and their references scanned to identify papers not identified in the initial search.

Inclusion criteria

The methodology was designed around the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” recommendations for improving the standard of systematic reviews[13].

Studies meeting the following criteria were included for review: (1) Language: Full article accessible in English language only; Conference abstracts only were excluded.(2) Patient population: Studies reporting outcomes in ≥ 10 male/female patients aged≥ 18 years with colorectal cancer and liver metastases. Where multiple publications were identified covering overlapping periods of time from the same institution/research group, the most recent and/or relevant data were selected for inclusion, and (3) Outcome measures: Studies were included if they reported oncological outcome data such as overall survival (OS), progression-free survival(PFS), recurrence-free survival (RFS) or disease-free survival (DFS). Studies reporting oncological outcomes for metastatic colorectal cancer were excluded if results were not reported for liver metastases specifically. Patients with metastases at multiple sites were included if one site was liver.

Data extraction

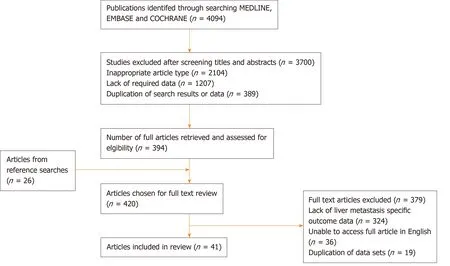

Three authors (Bingham G, Shetye A, Suresh R) independently extracted the following data from eligible studies: First author, year of publication, country of origin, study type, number of patients by gender, site of primary and age, primary study endpoint(s), secondary endpoint(s), extent and distribution of liver metastases,follow-up duration, adjuvant/neoadjuvant management, overall survival,progression-free survival, recurrence-free survival. Where there was uncertainty regarding inclusion a second author was consulted for consensus. All papers included were graded according to level of evidence using the system proposed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network[14]. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow-diagram summarising the above search strategy is provided in Figure 1.

RESULTS

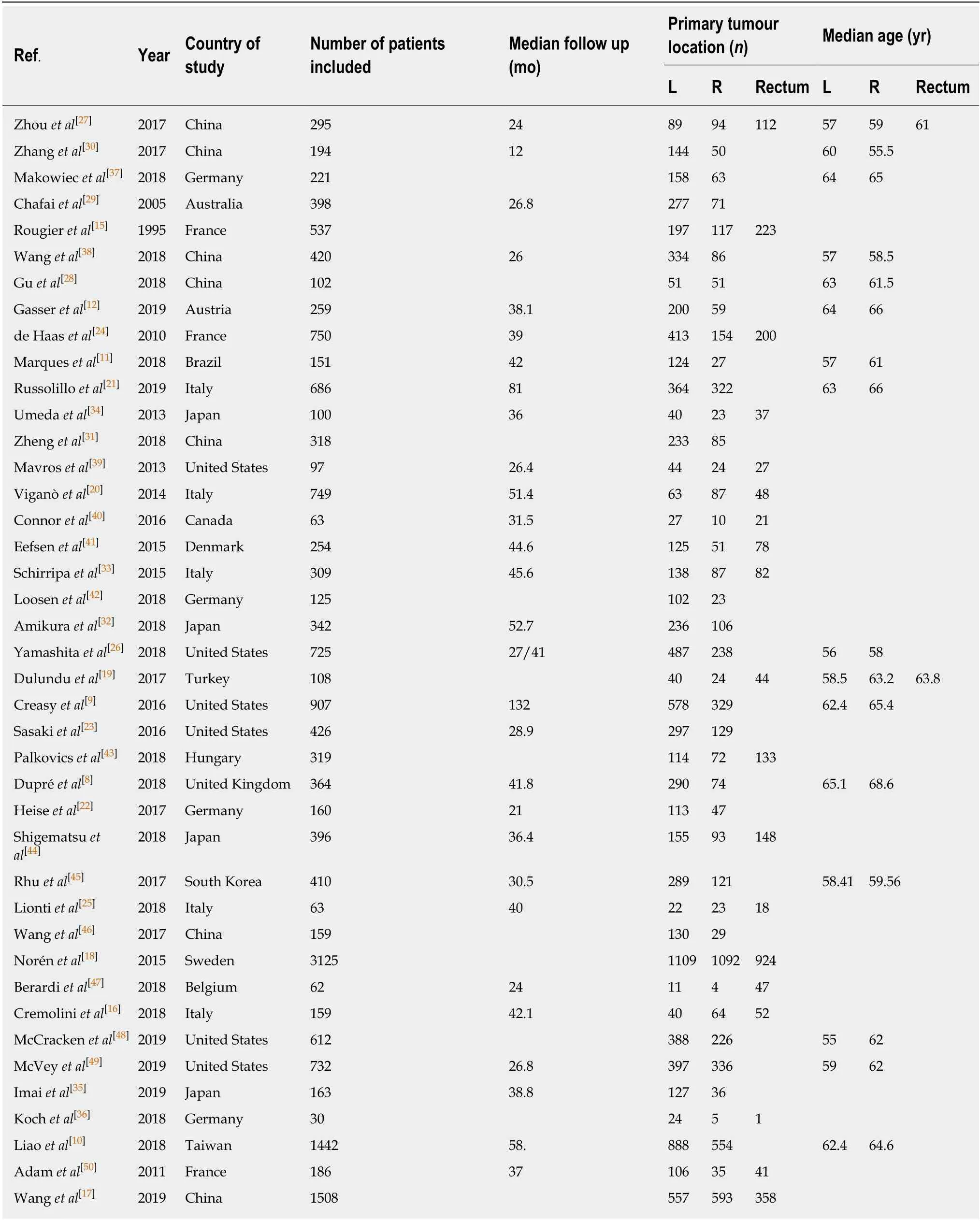

A total of 4094 potentially relevant publications were initially identified through the search strategy summarised in Figure 1. After screening of titles and abstracts, 3700 publications were withdrawn, leaving 394 articles for full text review. A reference search from these articles identified a further 26 studies of potential relevance. Of the 420 full text publications that were evaluated, 41 studies, including a total of 18426 patients, were found to meet our predefined inclusion criteria and were included in the review process. Study characteristics from these 41 studies are summarised in Table 1. Study population in these studies ranged from 24 to 3125 patients. Studies comprised two cohort prospective studies[15,16](evidence level 2+) and 39 retrospective studies (evidence level 2+ - 2++)[8-12,17-50], this included 6 papers with pooled analysis(evidence level 2+-2++)[10,12,15,16,18,49]. There were no randomised controlled trials.

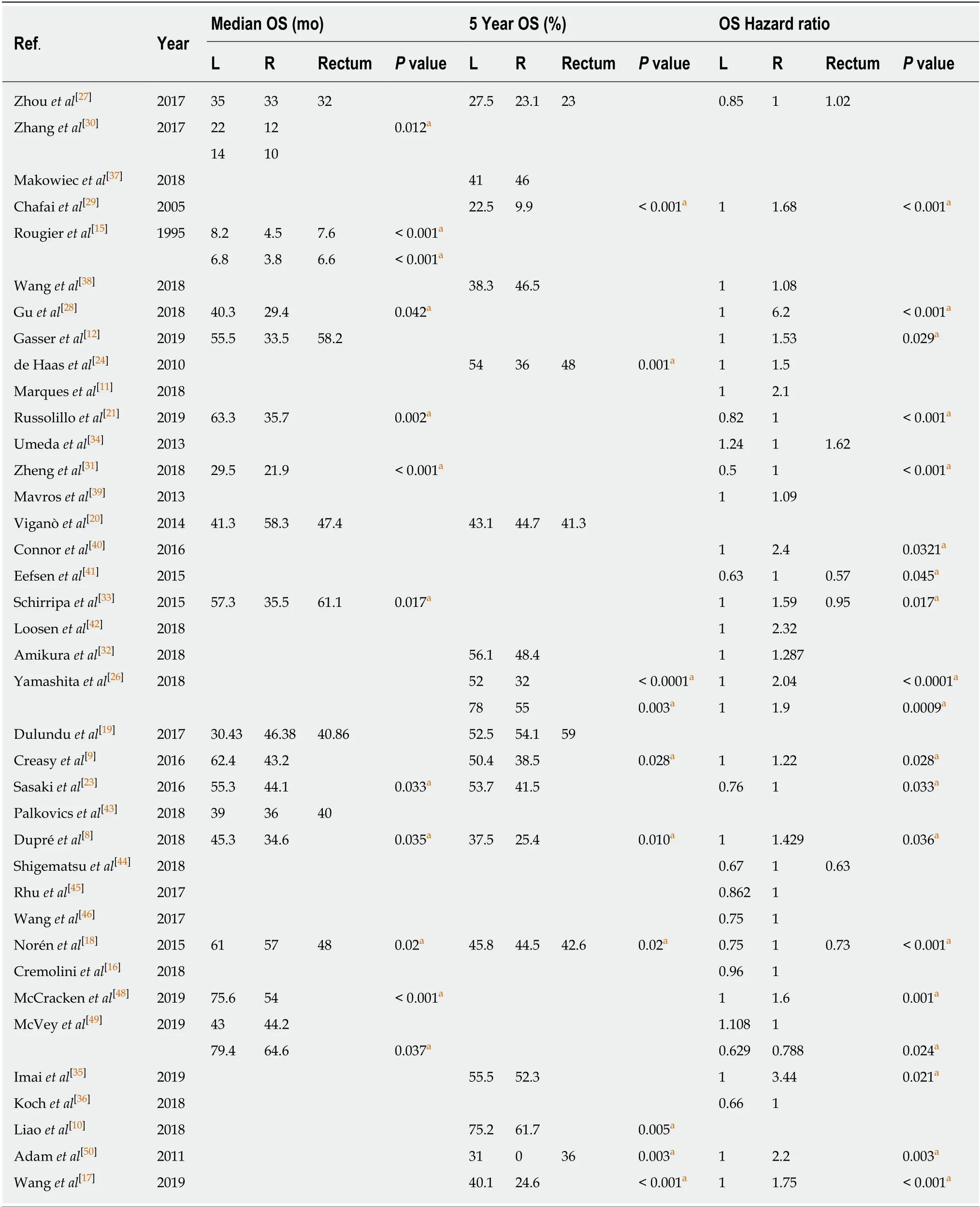

Overall survival

Data on the influence of PTL on OS in CRCLM was provided by 38 of the studies included for review, including a total of 18203 patients. In 21 of these studies (13897 patients -76.3% of the total patient population captured) a statistically significant trend was observed with improved OS in patients with left sided primary tumours undergoing treatment for CRCLM (l-CRCLM). For example, Wanget al[17]in their study of 1508 patients receiving surgical treatment for synchronous CRCLM, of which 593 had right sided primary colorectal tumours (r-CRCLM), found a significant difference in 5-year OS between left and right sided primaries (l-CRCLM 40.1%,r-CRCLM 24.6%,P< 0.001). They also found that patients withr-CRCLM were more likely to be T4 (31.3%vs20.1%,P< 0.001) N2 (42.5%vs31.8%,P< 0.001), and poorly differentiated (30.5%vs15.1%,P< 0.001). Creasyet al[9]in a similar cohort of 907 patients (36% with right sided primaries) undergoing hepatic resection found a found a median OS of 5.2 years inl-CRCLM compared with 3.6 years with inr-CRCLM (P=0.004), with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.22 (P= 0.028) on multivariate analysis. In their population database study of 3125 patients in Sweden Norénet al[18]found thatl-CRCLM extended median OS by 4 mo (P= 0.02) compared withr-CRCLM. In addition, the authors reported enhanced 5-year OS (45.8%vs44.5%P= 0.02), with a HR of 0.75 forl-CRCLM (P< 0.001).

Figure 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram summarising study selection process.

A further 17 studies with 4306 patients found no statistically significant difference in OS between the two groups, but there was a trend towards longer OS in patients withl-CRCLM on the whole. For example, Gasseret al[12]found patients with al-CRCLM had 22 mo longer median overall survival compared tor-CRCLM (P= 0.051).This contrasts with only 2 studies that showed lower OS in patients withl-CRCLM study, Dulunduet al[19]and Viganòet al[20], but neither with statistical significance (P=0.072 andP< 0.05 respectively). These results are summarised in Table 2.

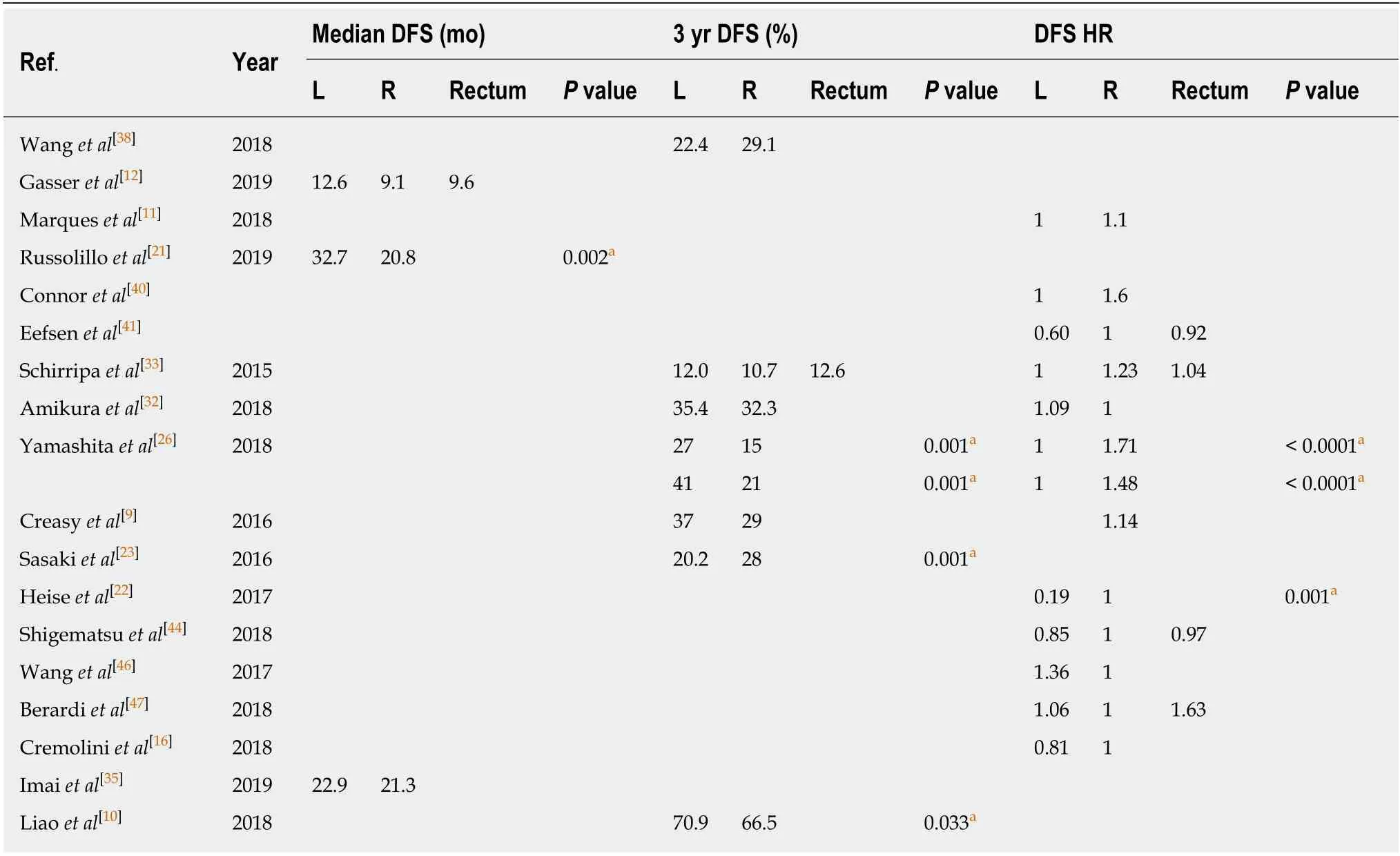

Disease-free survival

Benefit in DFS was also suggested, but not as convincingly as OS. This data was more sparsely provided, as some authors opted to alternatively provide PFS. Four studies including 3013 patients showed improved DFS inl-CRCLM. Russolilloet al[21]found improved median DFS by almost 1 year (32.7 movs20.8 mo,P= 0.002) in their 364 patients withl-CRCLM (vs322 patients withr-CRCLM) when assessing patterns of recurrence and survival following resection of liver metastases. In 2017 Heiseet al[22]reported a DFS benefit in patients withl-CRCLM undergoing repeat hepatectomy after recurrence of colorectal cancer (HR: 0.19,P= 0.001). Liaoet al[10]studied 1442 patients with stage III CRC who went on to develop CRCLM, and found that patients with left-sided colon cancer had better 3-year DFS (70.9%vs66.5%,P= 0.033)compared to those withr-CRCLM.

In contrast to these observations, only one study by Sasakiet al[23]found significantly improved 3-year DFS in patients withr-CRCLM (28%vs20.2%,P=0.001) in their study of 426 patients who were undergoing curative intent hepatectomy.

Thirteen studies with 3423 patients showed no significant difference in DFS betweenl-CRCLM andr-CRCLM. These results are summarised in Table 3.

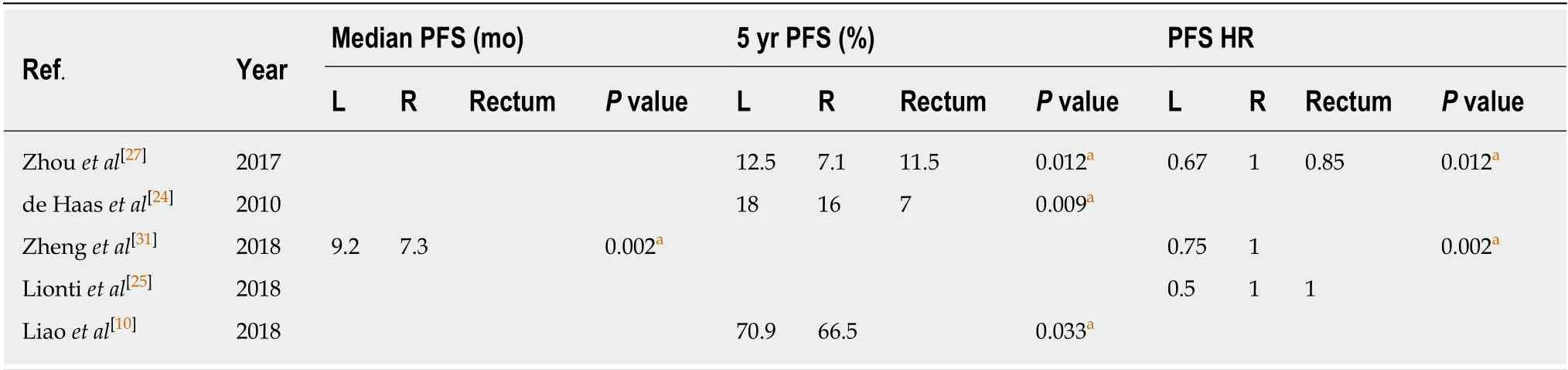

Progression-free survival

Only five publications provided data on PFS, and these data are summarised in Table 4. These studies including 2805 patients showed significantly improved PFS inl-CRCLM versusr-CRCLM. For example, de Haaset al[24]showed in 726 patientsundergoing hepatic resection for CRCLM, that patients withl-CRCLM had a higher 5-year PFS (18%vs16%,P= 0.009). No papers give significant evidence to the contrary and only one study with 63 patients showing no significant difference[25].

Table 1 Summary of characteristics of included studies

Table 2 Overall survival data

DISCUSSION

The data summarised in this systematic review appear to support the suggestion that CRCLM arising from right-sided colorectal primary tumours are associated withinferior OS compared with those arising from the left-sided CRC. Specifically, 21 of the 38 studies that provided data on OS reported statistically significant inferior OS in patients withr-CRCLM. Liaoet al[10]for example demonstrated in their large study of 1442 patients that patients withl-CRCLM had better 5-year OS, 5-year cancer-specific survival, and 5-year RFS, all with statistical significance. In 2018 Yamashitaet al[26]similarly concluded in their cohort of 725 patients undergoing upfront hepatic resection, that there was a significant survival benefit to havingl-CRCLM, but that this benefit was no longer evident after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The relationship between primary site and DFS and PFS with CRCLM is less clear, though again there appears to be a trend towards improved oncological outcome inl-CRCLM. Explaining these variations in oncological outcome is likely to require a deeper understanding of the underlying molecular and embryological differences associated with primary tumour sidedness.

Table 3 Disease free survival data

There are subtleties in regards to variable oncological outcome identified in this review that merit further discussion. For example, in terms of DFS, Sasakiet al[23]reported interesting findings in terms of patterns of relapse withl-CRCLM compared withr-CRCLM. Specifically, in their study patients withl-CRCLM exhibited a shorter disease-free interval compared with patients who had undergone treatment forr-CRCLM (P= 0.01). However, irrespective of timing of relapse, and in spite of a longer disease-free interval, when patients withr-CRCLM did succumb to hepatic recurrence, it was consistently found to be with more advanced disease (> 4 recurrent lesions,P< 0.01). As a result, the authors found significantly reduced OS and significantly reduced survival after recurrence inr-CRCLM, compared withl-CRCLM.Thus it is conceivable, for reasons as yet unclear, that the liver is able to “hold off”recurrence of hepatic metastases arising from right-sided primaries for longer, but also that when this does finally occur, it is a more aggressive pattern of progression,leading to the paradoxical observation in some studies of seemingly favourable disease free interval, but ultimately inferior OS withr-CRCLM.

Previously the suggestion has been made that the typically more indolent course of presentation of right CRC, might in part be responsible for inferior outcome with resulting liver metastases[10]. The notion here is that delayed diagnosis of primary tumour results in an increased risk of developing synchronous metastases which are then incurable[51]. This would mean potentially fewer curative-intent resections offeredto these patients, resulting in observed abbreviated survival. However, in this study we have also shown that there is evidence that PTL also has prognostic impact in patients with unresectable disease from the outset. For example, Zhouet al[27]reported on outcomes in 295 patients with unresectable CRCLM undergoing palliative radiofrequency ablation, and found similar rates of OS, but that the PFS was significantly better in patients withl-CRCLM (HR: 0.67,P= 0.012). Guet al[28]also reported outcomes following palliative-intent radio-frequency ablation in patients with CRCLM, finding that patients withl-CRCLM had a significantly lower risk of recurrence outside of the ablation zone, with increased OS of 40.3 mo compared with 29.4 mo inr-CRCLM(P= 0.042). Multivariate analysis confirmed a HR of 6.2 (P=0.001) forr-CRCLM predicting OS. This data is further supported by findings reported by Chafaiet al[29]in 2005, who studied patients with unresected synchronous liver metastases after resection of the primary tumour. They found a significantly shorter survival in palliative patients who hadr-CRCLM compared withl-CRCLM (2 years survival 9.9%vs22.2%, HR: 1.5P< 0.001). In circumstances where palliative/debulking surgery is offered, differences continue to persist for l-CRCLM versus r-CRCLM. For example, in 2017 Zhanget al[30]found that hepatic palliative resection prolonged median OS by 8 mo in patients withl-CRCLM (palliative resectionvsno resection: 22 movs14 mo,P= 0.009); however, by comparison no such improvement in OS was observed for patients withr-CRCLM undergoing palliative resection (12 movs10 mo,P= 0.910).

Table 4 Progression free survival data

With regards to defining putative mechanistic explanations for these differences, a number of factors should be considered. Firstly, there is considerable evidence that right sided CRCs are significantly more likely to harbor negative prognostic features;they tend to present at a more advanced stage, often in older patients, with a greater chance of synchronous metastatic disease, are more likely to carry unfavourable genetic mutation(s), and show poor differentiation[18,21,27,31,52]. It could therefore follow that patients with right sided CRC simply present with more advanced and aggressive disease from the outset. This however was not a uniform finding across the studies included in this review. For example, Creasyet al[9]found no such differences between right sided versus left sided CRC in terms of proportion of patients with the largest metastasis > 5 cm, proportion of patients with multiple metastases, or the proportion of patients with extra-hepatic disease. In spite of this relative equipoise,the authors reported significantly improved OS in patients withl-CRCLM and suggest that unique differences based on sidedness are likely to exist that extend beyond the aforementioned conventionally accepted differences.

From this perspective a number of mechanisms have emerged that could play a role in contributing to the inferior oncological outcome observed in patients withr-CRCLM. These broadly can be considered as: (1) Molecular differences; (2)Histopathological differences; (3) Therapeutic sensitivity differences; and (4)Embryological differences.

Molecular differences

There are well-established molecular differences between right- and left-sided CRC with the former more often exhibitingKRASand/orBRAFmutation[12,33,34,53]. RAS mutations have consistently been found to be associated with more aggressive tumour biology and are identified in up to 45% of patients with metastatic CRC. For example, the studies published by Amikuraet al[32]and Shindohet al[54]both demonstrate that RAS mutational status is associated with significantly worse survival in CRCLM (Amikuraet al[32]: 5-year OS: 42.4%vs65.3%,P= 0.0006; Shindohet al[54]: 3-year DFS 59.9vs83.6%P= 0.016). Of note, it has also been reported that among patients put forward for curative intent resection of CRCLMs, the incidence of RAS mutation is only around 10%-15%, indicating that underlying tumour biology,seemingly inseparably linked to PTL, exerts additional prognostic relevance as it appears to indirectly influence surgical candidacy[55]. Goffredoet al[56]evaluated outcomes in 2655 patients undergoing CRCLM resection. They observed a significant increase in likelihood of mutant KRAS with right-sided PTL, compared to left and correspondingly found reduced OS in patients withr-CRCLM. It is likely that additional molecular drivers are responsible for the variations seen according to PTL,and RAS/BRAF likely account for only part of the molecular landscape especially since only a limited proportion of these cases are put forward for resection[54]. This notion is supported by Huanget al[57]who found no significant association between KRAS/BRAF mutational status and prognosis in patients presenting with metachronous CRCLM.

The role of mismatch repair (MMR) status and microsatellite instability (MSI) in the context of PTL seems less certain. Right sided CRC is more frequently associated with deficient MMR and MSI[7,56,58]. These tumours tend to be typified by poor differentiation, mucinous features and lymphocytic invasion. Evidence supports the suggestion that MSI is associated with improved oncological outcome[59,60]. However,this is at odds with the findings of the present review, wherer-CRCLM appears to have shortened survival. This may reflect fundamental differences in MMR status according to tumour stage. For example, Jernvallet al[61]found MSI to be a more common finding in right sided Stage II CRC, but this was less frequently observed in stage IV disease. In this review molecular data were only available from a limited number of publications and subdivision of molecular phenotype according to PTL has not been provided in most cases. Hence, we are not able to draw any more definitive conclusions on the precise interplay between molecular factors and PTL. Considering these limitations, The Cancer Genome Atlas Network sought to evaluate a broader panel of genetic mutations and defined cases as “hypermutated” where a mutation rate of > 12/106bases was found. Out of 276 samples analysed, the majority of hypermutated cases were right sided primary tumours. The group suggest that hypermutated phenotype is a significant negative prognostic feature, and this may in part account for inferior survival withr-CRCLM, as noted in the present review[62].

Histological differences

Several investigators have evaluated tumour histopathological features in order to determine if the difference in sidedness outcomes and tumour aggressiveness can be explained by one or more of these. Desmoplastic growth behaviour, presence of poorly differentiated clusters and tumour budding have all been considered[25,41,63].Strong evidence, however, relates to the prevalence of mucinous elements. Viganòet al[20]and Russolilloet al[21]have both demonstrated mucinous adenocarcinoma to be more prevalent in right-sided CRC (P= 0.002 andP= 0.001, respectively). Viganòet al[20]reported significantly shortened OS withr-CRCLM versusl-CRCLM. They observed that, when compared with non-mucinous carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma has a higher KRAS mutation rate 61.8%vs36.4%;P= 0.037) and lower chemotherapy response rate (63.9%vs85.2%;P= 0.006). Specifically, Viganòet al[20]reported lower 5-year OS (33.2%vs55.2%;P= 0.010) and DFS (32.5%vs49.3%;P= 0.037) for mucinous tumours undergoing hepatic resection. One can extrapolate from these observations that inferior survival and right sided PTL are linked by an increased tendency for mucinous histology.

Therapeutic sensitivity differences

There are also suggestions in the literature that chemosensitivity is important in predicting survival, and that there may be a differing chemosensitivity profile according to PTL. In their meta-analysis of 16 first-line trials evaluating the efficacy of chemotherapy alonevschemotherapy with targeted biologics in patients with unresectable metastatic CRC, Youet al[64]found survival of patients with right sided CRC was inferior to those with left in patients receiving chemotherapy alone,implying that right-sided tumours overall are less chemosensitive. This finding is supported by Yamashitaet al[26]found thatr-CRCLM were independently associated with “minor pathological response” (defined as cancer cells accounting for ≥ 50% of residual cells), and were thus less sensitive to chemotherapy with worse RFS and OS.Interestingly, Marqueset al[11]found that when selecting patients for CRCLM resection based on chemosensitivity, the survival disadvantage seen withr-CRCLM was eliminated. This suggests fundamental differences in tumour biology with the less chemosensitive phenotype more frequently seen with right-sided PTL and in turn associated with poorer survival.

This difference is maintained after the addition of well-established antiangiogenic biologics. Youet al[64]found inferior survival in patients withr-CRCLM receiving chemotherapy and bevacizumab compared withl-CRCLM. Zhenget al[31]studied the effect of cetuximab as an addition to chemotherapy in KRAS wild-type patients with initially unresectable hepatic metastases. They found a survival benefit to cetuximab in patients with bothr-CRCLM andl-CRCLM, but importantly noted that this effect was more substantial in the latter, with higher rates of effective tumour downstaging and extended OS.

Embryological differences

In terms of embryology, Yamashitaet al[26]suggest that the mid-gut embryological origin of the right colon may be responsible for the variable responsiveness ofr-CRCLM to chemotherapy and differing oncological outcomes. Specifically, in their study of outcomes in 725 patients, they found reduced responsiveness to chemotherapy, reduced RFS and reduced OS in patients withr-CRCLM. The authors reported that this difference was maintained irrespective of RAS mutational status,which is considered to be one of the key oncogenic differences between right- and leftsided colon cancers. It is possible however, that other factors centered around the distinct development of these regions of gut, including unique lymphatic and venous drainage basins, and exposures to unique types of bacterial flora, could be contributing to oncological variability. This is an area that requires further research.

Limitations

As a systematic review this paper has some inherent limitations, it is restricted by the quality of the literature available. However, all included papers were graded using the SIGN criteria with small studies excluded to mitigate this. Care was taken to perform a complete literature search, but studies and some work in progress may have been missed. Larger studies and well as future meta-analysis will be necessary to more clearly establish this trend and may provide a deeper understanding of the mechanisms at play.

In conclusion, the present review provides compelling data to support the notion that PTL significantly influences oncological outcome in patients with CRCLM.Overall, the data presented indicate that patients withr-CRCLM appear to have truncated overall, disease-free and progression-free survival. Some of these differences are likely to be accounted for by molecular heterogeneity, but other factors such as embryological origin and colonic microbiotal composition are areas that have received comparatively less attention in terms of research, and these may represent promising avenues to explore in the future. With the understanding that PTL could have prognostic relevance, comes the need to adjust treatment pipelines for patients accordingly. For example, patients with right-sided CRC may require abbreviated intervals between surveillance scans and tumour-marker assessment after primary tumour resection. In addition, given their more aggressive pattern of recurrence after hepatic resection/treatment, patients withr-CRCLM may benefit from a more radical first-line treatment of hepatic metastases. For example, the role of non-anatomical resection and the use of locally-ablative techniques inr-CRCLM may need more careful consideration.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cause of cancer related death with liver being the most common metastatic site. It has been long suggested that left and right sided primary tumours exhibit different behaviour but relatively little has been written about how this relates specifically to outcomes in colorectal cancer with liver metastases (CRCLM).

Research motivation

To improve current understanding regarding the impact of PTL on CRCLM given the relative paucity of information in this area. This in turn could have a significant impact on patient morbidity and mortality.

Research objectives

To ascertain whether there is a significant difference in oncological outcome in patients with CRCLM depending on PTL and to present some hypotheses that may explain any differences found. This systematic review demonstrates a significant difference in outcomes based on PTL with inferior oncological outcome for patients with right-sided CRC. . Further work is needed to better characterise the mechanisms responsible for this variation in order to inform clinical decision making.

Research methods

A systematic review of Medline, Cochrane and Embase using the Terms “The medical subject heading terms and key words used are as follows: “Colon” or “rectal cancer”, “liver metastasis”or “liver metastases” or “hepatic metastasis” or “hepatic metastases” and “left” and “Right”.This search was combined with a bibliographic search to find the relevant publications and extract data from these papers. The methodology was based around the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses’ recommendations for systematic reviews

Research results

Twenty-one studies with a total of 18203 patients showed a statistically significant trend of improved overall survival in patient with left sided primary tumours undergoing treatment for colorectal cancer liver metastases (l-CRCLM). Four studies including 3013 patients showed improved disease free survival (DFS) inl-CRCLM. Only five publications provided data on progression free survival (PFS). These studies including 2805 patients showed significantly improved PFS inl-CRCLMvs r-CRCLM. The findings of this review are congruent with the accepted premise of superior survival in left sided colorectal cancer, and uniquely show that this remains true in the context of metastatic liver disease. We highlight a number of factors that may contribute to this, including KRAS/BRAF mutational status, presence of mucinous elements, and impaired chemosensitivy –all which are shown to be associated with right-sided PTL. The exact interplay between these known factors, PTL, and the emerging new mutations and molecular markers is yet to be determined and work needs to be done to determine the importance of PTL within the conglomeration.

Research conclusions

The findings of this review indicate that PTL may have a role as an independent prognostic factor when determining treatment and disease surveillance strategies specifically in colorectal cancer that has metastasised to the liver. We find improved survival for both resected and unresectablel-CRCLM as well as a maintained trend after addition of biologics to established chemotherapy regimens. Hepatic recurrence after treatment of CRCLM appears to occur more aggressively with right-sided CRC, conferring significantly reduced survival. Explaining these variations in oncological outcome requires a deeper understanding of the underlying molecular and embryological differences associated with primary tumour sidedness. Microsatellite instability, interestingly, whilst more common in right-sided tumours, has been shown to be independently associated with improved survival – a finding somewhat incongruent with the overall picture of inferior survival inr-CRCLM. This suggests alternative mechanisms beyond MMR and microsatellite instability are likely to be involved. KRAS and BRAF mutational status,mucinous adenocarcinoma, and impaired chemosensitivity are all known to be significantly associated with right-sided CRC, and we show here that this association and the accompanying inferior survival persists inr-CRCLM. A better understanding of the role of PTL in the oncological outcomes of metastatic CRC may allow for improved risk stratification and redesigned patient pathways.

Research perspectives

There is a considerable amount of data available on the oncological outcomes of patients undergoing liver resection for CRCLM, as related to PTL. This shows with convincing evidence that outcomes are superior for patients withl-CRCLM. Future research should be focused on gathering associated molecular and genetic data as related to PTL to better understand the tumour biology of right-sided CRC. This may allow the determination of ideal molecular markers, both for risk stratification/prognostication, and that may be used as potential therapeutic targets.