不同品种茶树根际AM真菌群落结构分析

2020-06-15何斐李冬花卜凡

何斐,李冬花,卜凡

不同品种茶树根际AM真菌群落结构分析

何斐,李冬花,卜凡

安康学院现代农业与生物科技学院,陕西 安康 725000

对陕西安康汉水韵茶园栽培的5个品种茶树根际丛枝菌根(Arbuscular mycorrhiza,AM)真菌群落结构特征进行分析,以期丰富我国茶树AM真菌种质资源库。结果表明,不同品种茶树根际AM真菌种丰度及种属组成等存在差异。其中,紫阳群体种茶树根际分离的AM真菌最多(6种),陕茶1号、龙井长叶、龙井43和福鼎大白茶各分离到5、4、4种和3种。龙井长叶茶树根际AM真菌孢子密度最高(每克干土含3.57个孢子),龙井43最低(每克干土含1.10个孢子)。紫阳群体种茶树的AM真菌物种多样性Shannon-Wiener和均匀度指数均达到最高,分别为0.63和0.096,龙井长叶最低(0.18和0.027)。龙井长叶的菌根定殖率最高(29.5%),福鼎大白最低(15.8%)。不同茶树品种AM真菌种类组成的相似性系数维持在0.111~0.750,其中,龙井长叶与龙井43茶树根际AM真菌种类组成相似性系数最高,而福鼎大白和紫阳群体种相似性系数最低。研究表明,不同品种茶树根际AM真菌群落结构存在一定的差异,根际土壤中鉴定的AM真菌资源对进一步筛选和研发茶树专用AM真菌菌剂,促进茶产业发展具有重要意义。

AM真菌;茶树;品种;群落结构

丛枝菌根(Arbuscular mycorrhiza,AM)真菌作为生态系统中一类与宿主植物互惠共生的生物群落,其在与宿主进行物质交换、能量转移、信号传递及稳定生态平衡等过程中发挥着至关重要的作用[1]。AM真菌以多物种构建的生物群落发挥其生理生化及生态效应,且不同的AM真菌群落结构所产生的功能不同。大量研究证明,土壤养分[2]、土层深度[3]、气候[4]、农业管理措施[5]、植被[6]等因子,尤其是宿主植物[7-8]对AM真菌群落结构和多样性有重要影响。张海波等[7]研究认为,在黄壤土中生长的单性木兰(Dandy)比紫弹树(Pamp)和红锥()更有助于维持较高的AM真菌物种丰富度和群落多样性。蔡邦平等[8]研究表明,云南昆明不同品种梅花生长状况与其根围土壤AM真菌种类或孢子密度密切相关:根际AM真菌种类多、孢子密度大的梅花植株生长更好。任禛等[9]在分子水平上证明了AM真菌多样性及群落结构受宿主植物品种的影响,侵染4个品种烟草根系的主要AM真菌类型相同,但稀有AM真菌类型明显不同。因此,研究同种植物的不同品种对AM真菌群落结构的影响,可为作物品种选育及作物(特定品种)专用AM真菌菌剂的研发提供参考。

茶树(L.)系山茶科山茶属多年生木本常绿植物,富含茶多酚、氨基酸、生物碱等多种功能成分,亦具有水土保持、文化旅游等方面的价值,是我国重要的经济作物之一[10-11]。据统计,截止2018年,我国茶园面积约为289.9万hm2,茶园面积和产量均为世界第一[12]。自上世纪初首次发现茶树根际存在丛枝菌根以来,大量调查研究表明,AM真菌广泛存在于茶园土壤中[10,13-14]。但是目前我国茶树AM真菌资源调查尚不系统,在某些茶区仍属空白。

安康茶区地处陕西省秦岭南麓、大巴山腹地。该区域终年温暖湿润,雨量充沛,气候和土壤均有利于茶树的种植与生长[15]。但是,目前尚无有关安康茶区茶树AM真菌的研究报道,而调查茶园土壤中AM真菌群落结构可为进一步收集、筛选及研发茶树专用AM真菌菌剂奠定基础。因此,本研究对安康茶区汉水韵基地同一茶园不同品种茶树根系AM真菌定殖率、群落结构及多样性进行了研究,以期丰富我国茶树AM真菌种质资源库,为菌根技术在茶产业中的应用提供具有价值的菌种资源,也为筛选和研发茶树品种相应的专一AM真菌菌剂奠定基础。

1 材料与方法

1.1 研究区域概况

研究地点位于陕西省安康市安康汉水韵茶叶有限公司生产基地。安康市位于陕西省东南部(31°42′~33°49′N、108°01′~110°01′E),属亚热带大陆性季风气候,年均气温14.5℃,极端最低气温–16.4℃,年均降雨量945 mm,年均日照时数1 610 h。基地茶园占地面积40 hm2,其中双龙镇基地茶园占地200 m2。2012年在双龙镇基地茶园同一田块种植有龙井长叶、龙井43、陕茶1号、福鼎大白及紫阳群体种5个茶树品种。所有品种的茶树栽培、施肥、修剪及采摘等管理方法相同。

1.2 样品采集

2017年5月,在安康市汉滨区双龙镇汉水韵茶叶有限公司基地茶园的同一地块采集不同品种茶树根际土壤及根系。选取5个茶树品种:龙井长叶(LJCY)、龙井43(LJ43)、陕茶1号(SC1)、福鼎大白(FDDB)及紫阳群体种(ZYQT),每个茶树品种选取3株,于植株根际定点采集土样,其土壤为黄棕壤,pH 5.68,有机质11.65 g·kg-1,全氮0.87 g·kg-1,速效磷16.79 mg·kg-1,速效钾52.27 mg·kg-1。去除土壤表面枯枝落叶,距植株主干0~30 cm处,沿主根系采集0~20 cm土层范围内带有细根的根系,以及距离根表9 mm以内的根际土壤1~2 kg,编号并详细记录采样时间、地点、茶树品种等信息。

1.3 试验方法

1.3.1 AM真菌定殖率测定

从采集的土样中挑选出茶树细根,自来水冲洗干净,将根样剪成约1 cm长根段,按照Phillip等[16]和柳洁等[17]方法测定AM真菌定殖率。丛枝、泡囊和菌丝定殖率分别为丛枝、泡囊和菌丝定殖根段占总观测根段的百分比。菌根定殖率的高低参照文献[18]划分为5个侵染等级。

1.3.2 AM真菌孢子的分离鉴定

采用湿筛倾析法[19]分离、镜检孢子,记录孢子数量、孢子的大小、颜色、形态和连孢菌丝等显微特征。根据《VA菌根真菌鉴定手册》[20]、国际AM真菌保藏中心INVAM(http://invam.caf.wvu.edu)最新分类描述和图片,并参照近几年发表的新记录种和新种[21-22]对AM真菌孢子进行鉴定。

1.3.3 AM真菌孢子密度、分离频度、种丰度和相对多度

称取100 g风干土壤,采用湿筛倾析法[19]分离AM真菌孢子,在体视显微镜下记录孢子数量,以每克风干土中统计的孢子数量计为孢子密度。

AM真菌孢子的分离频度(Frequency,)[23]、种丰度[24]和相对多度[25]分别按照下列公式计算:

分离频度()=(某AM真菌属或种出现的样本数量/土样总的样本数量)×100%

将AM真菌优势度按分离频度()划分为5个等级:>80%为优势属(种),60%<≤80%为最常见属(种),40%<≤60%为常见属(种),20%<≤40%为少见属(种),≤20%为偶见属(种)[18]。

种丰度:每个土壤样品中AM真菌孢子种的数量,本文指每个茶树品种根际土壤中AM真菌孢子的种数。

相对多度=(某样方中某种AM真菌孢子数量/某样方中AM真菌孢子总数)×100%

1.3.4 AM真菌物种多样性指数

采用Shannon-Wiener指数[26]和均匀度Pielou指数(Evenness,)[27]来描述AM真菌多样性特征,分别用下列公式进行计算:

′=﹣∑(P×lnP)

′=﹣∑(P×lnP/ln)

式中:P=N/,N为种的数量,为样方中AM真菌孢子总数,为种所在土壤样方中种的数目。

1.3.5 AM真菌种类组成相似性系数

按照Sorenson系数[28]公式计算不同品种茶树AM真菌种类组成相似性系数:

=2/(+)

式中:为某品种茶树根际AM真菌种类数目;为另一品种茶树根际AM真菌种类数目;为两品种茶树根际共同存在的AM真菌种类数目。

1.4 数据处理

采用SPSS 17.0统计软件分析试验数据,用Duncan新复极差法进行方差分析和差异显著性检验(<0.05)。采用SigmaPlot 10.0软件作图。

2 结果与分析

2.1 AM真菌定殖状况

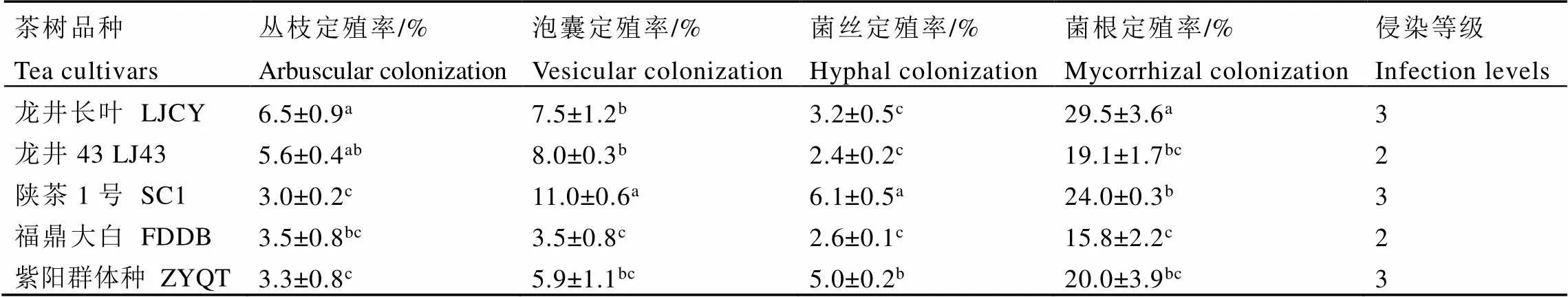

由表1统计结果可知,5个品种茶树根系均被AM真菌侵染,菌丝和泡囊是AM真菌定殖的主要形式,说明AM真菌能与茶树根系形成一定的共生关系。但菌根定殖率普遍较低,侵染等级为2、3级。其中,定殖率最高的为龙井长叶(29.5%),侵染等级3级;定殖率最低为福鼎大白(15.8%),侵染等级2级。龙井长叶的丛枝定殖率最高(6.5%),而陕茶1号丛枝定殖率最低(3.0%),但陕茶1号的泡囊和菌丝定殖率均显著高于其他品种,其分别达到11.0%和6.1%。

2.2 AM真菌种质资源及分离频度

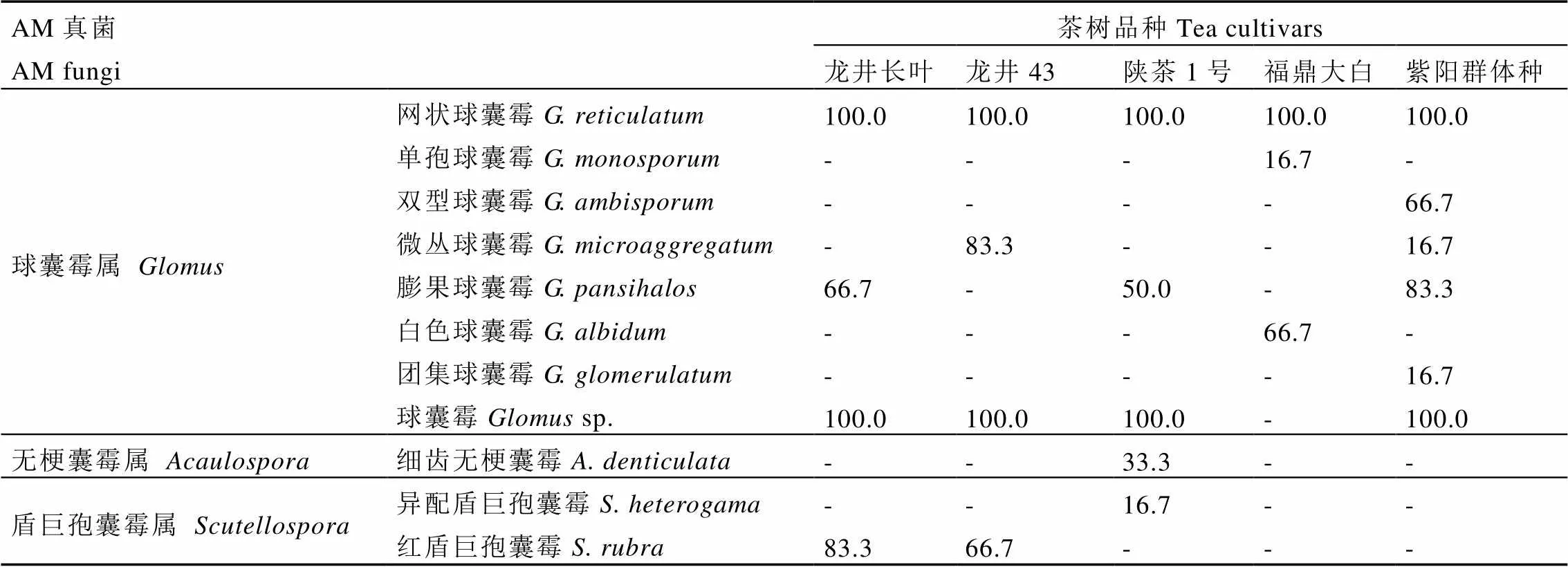

由表2可知,本研究从5个品种茶树根际土壤中共鉴定出3属11种AM真菌,其中10种鉴定到种,1种孢子鉴定到属。包括球囊霉属()8种,无梗囊霉属()1种,盾巨孢囊霉属()2种。

无梗囊霉属唯一一种AM真菌细齿无梗囊霉()和盾巨孢囊霉属的AM真菌异配盾巨孢囊霉()均只出现在陕茶1号根际土壤中,均为少见种。红盾巨孢囊霉()在龙井长叶和龙井43茶树根际土壤中被分离检出,分别为龙井长叶的优势种(=83.3%)和龙井43的常见种(=66.7%)。

表1 不同品种茶树AM真菌定殖状况

注:同列数据后不同小写字母表示差异显著(<0.05),下同

Note: Data in the same column with different lowercase letters indicate significant differences at<0.05 according to Duncan’ test. The same below

表2 不同品种茶树根际AM真菌种类和分离频度

注:-表示未检出,下同

Note: -, no detected, the same below

球囊霉属的种类占绝对优势,在各品种茶树根际土壤中均有分布,是其共同优势属。其中,网状球囊霉()在5个品种茶树根际均有分布,是其共同优势种。单孢球囊霉()和白色球囊霉()均只分布在福鼎大白茶树根际,其分别为福鼎大白的偶见种(=16.7%)和常见种(=66.7%)。团集球囊霉()和双型球囊霉()仅在紫阳群体种茶树根际土壤中被检出,分别为紫阳群体种的偶见种(=16.7%)和常见种(=66.7%)。

2.3 AM真菌种丰度、孢子密度和相对多度

由表3可看出,不同品种茶树根际土壤中AM真菌种丰度、孢子密度和各属的相对多度存在明显差异。其中,孢子密度最大的是龙井长叶(每克干土含3.57个孢子);孢子密度最小的是龙井43,每克干土含1.10个孢子。紫阳群体种的AM真菌种丰度(5.67)显著高于其他4个品种,而福鼎大白的AM真菌种丰度最低,为2.83。不同品种茶树根际AM真菌各属的相对多度变化趋势基本一致,均表现为球囊霉属>盾巨孢囊霉属≥无梗囊霉属。

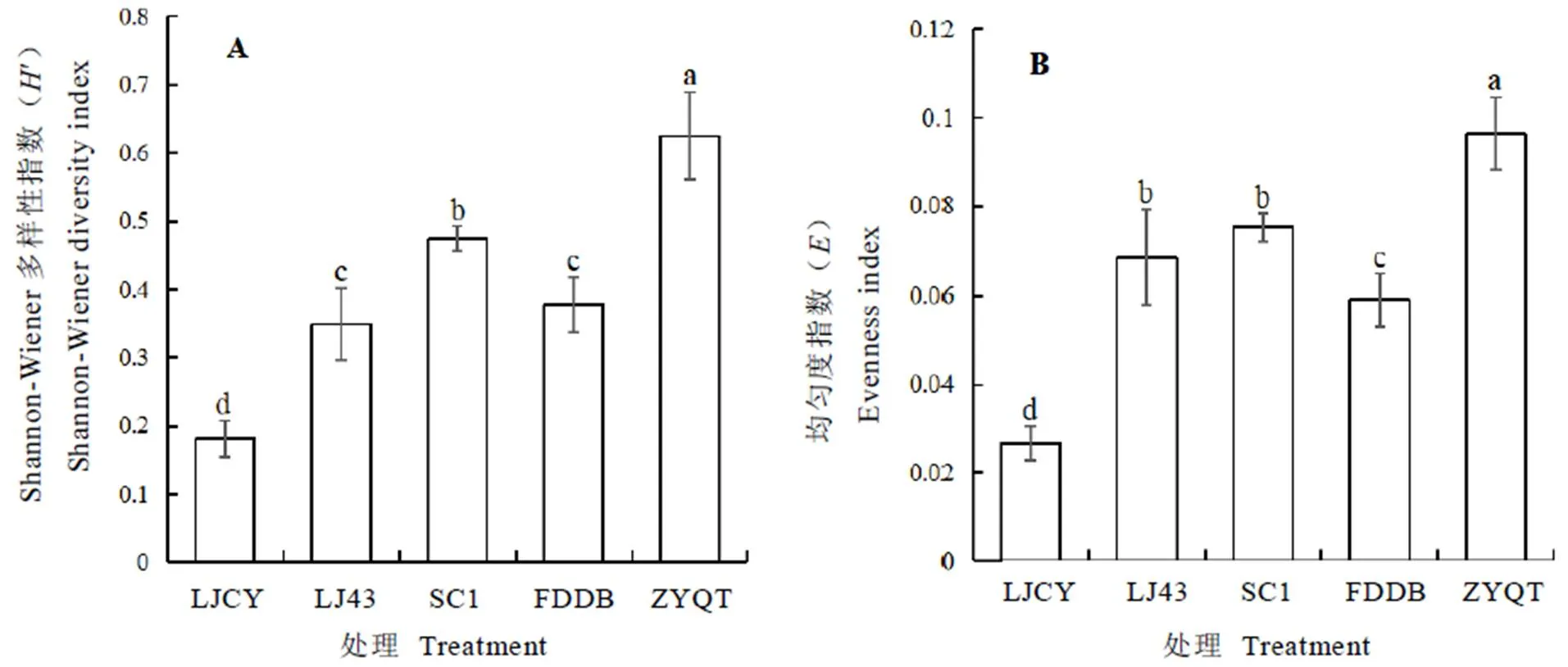

2.4 AM真菌物种多样性指数

由图1可知,不同品种茶树根际AM真菌的物种多样性存在明显差异。其中,紫阳群体种茶树根际AM真菌的Shannon-Wiener指数(′,图1-A)和均匀度Pielou指数(,图1-B)均显著高于其他4个品种,分别为0.63和0.096;而龙井长叶的和值均最低,分别为0.18和0.027。

表3 不同品种茶树根际AM真菌种丰度、孢子密度及属的相对多度

注:数值为平均值±标准差(n=3)。误差线上不同小写字母表示Duncan检验差异显著(P<0.05)

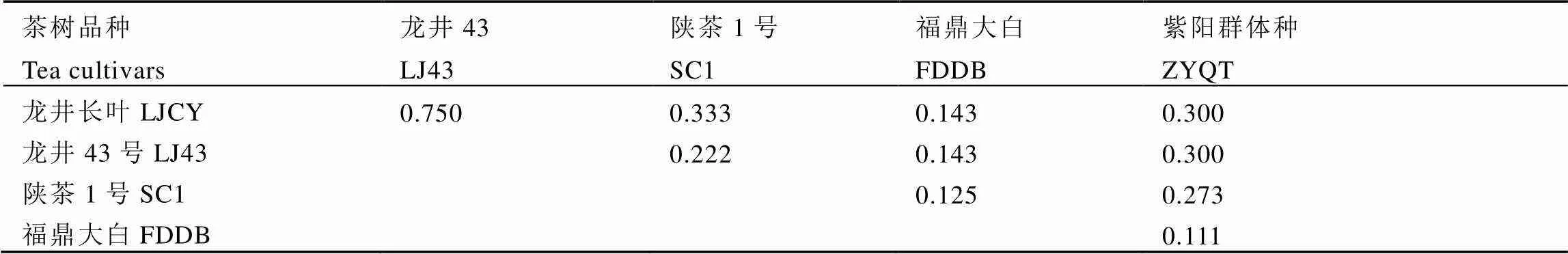

2.5 AM真菌群落组成相似性系数

不同品种茶树根际土壤中AM真菌群落组成的相似性系数维持在0.111~0.750。其中,龙井长叶与龙井43的相似性系数最高,而福鼎大白与紫阳群体种的相似性系数最低。福鼎大白与龙井长叶、福鼎大白与龙井43的相似性系数相同,均为0.143。紫阳群体种与龙井长叶、紫阳群体种与龙井43的相似性系数也相同,均为0.300(表4)。

3 讨论

AM真菌的生存和生长发育依赖宿主植物提供所必需的碳水化合物[29],不同植物甚至同种植物不同品种的生理生化代谢特性、根系形态与分泌物等差异必然影响AM真菌对宿主植物的识别与侵染,进而影响AM真菌的生长、产孢及群落组成等[30-31]。因此,宿主植物甚至品种是影响AM真菌群落结构的一个重要因素[32]。本研究表明,茶树的不同品种影响AM真菌的定殖率和种属构成,且导致其种丰度、相对多度、多样性指数及相似性系数等群落结构差异,说明同种植物不同品种能抑制或促进某些AM真菌的生长,进而影响AM真菌的群落结构特征。茶树遗传来源复杂,形态变异多样,不同品种茶树遗传物质不同[33],其根系分泌物化学成分必然也存在差异,继而影响与根系共生的AM真菌定殖率和AM真菌群落结构等。不同茶树品种的作用机制除了基因型[34]和生理特性[35]差异外,其他作用机制有待进一步研究。

近年来,刘辉等[10]从安徽茶区鉴定出8属36种AM真菌,其中缩管柄囊霉()是优势种。吴丽莎等[36]从青岛崂山茶区鉴定出3属22种AM真菌,其中无梗囊霉属()和球囊霉属()为优势属。Singh等[14]从印度古毛恩地区自然和耕作条件下茶树根际土壤中鉴定出4属51种AM真菌。卢东升等[37]从豫南茶园鉴定出4属12种AM真菌,其中光壁无梗囊霉()、幼套球囊霉()和聚丛球囊霉()是该茶园的优势种。吴铁航等[38]从江西余江红壤茶园土壤中分离鉴定出4属7种AM真菌,其中细齿无梗囊霉()是优势种,丽孢无梗囊霉()是偶遇种。本研究从安康茶区5个品种茶树根际土壤中分离获得3属11种AM真菌,其属和种相对较少。不同品种茶树根系均能被AM真菌定殖,但菌根总定殖率差异不大,侵染等级大多为3级,菌根定殖率最高为龙井长叶(29.5%)。菌根定殖率普遍偏低,AM真菌种类相对较少,这可能与该茶园土壤被长期耕作或海拔较低(约600 m)有一定的关系,但仍有待于与其他茶产区进行比较研究。

本研究中,球囊霉属在5个常见品种茶树根际土壤中普遍存在,证实球囊霉属是广谱生态型[39]。其中,网状球囊霉(.)是龙井长叶、龙井43、陕茶1号、福鼎大白及紫阳群体种茶树根际土壤中共同存在的优势种。有研究表明,网状球囊霉在荒漠地区[40]、新疆艾比湖流域[41]、松嫩草地[42]、河北峰峰矿区[43]、内蒙古农牧交错区[44]等均有分布,说明该种AM真菌适应能力强。网状球囊霉可能适应偏酸性的土壤条件,从而成为该茶园的优势种,这可能也与其本身的生物学特性有关。其有关适应机制与接种效应有待于进一步研究,以期为利用该优势菌种制备茶树专用菌剂提供技术依据。

表4 不同品种茶树根际AM真菌群落组成相似性系数

[1] 李元敬, 刘智蕾, 何兴元, 等. 丛枝菌根共生体中碳、氮代谢及其相互关系[J]. 应用生态学报, 2014, 25(3): 903-910. Li Y J, Liu Z L, He X Y, et al. Metabolism and interaction of C and N in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis [J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2014, 25(3): 903-910.

[2] Zhu C, Tian G L, Luo G W, et al. N-fertilizer-driven association between the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal community and diazotrophic community impacts wheat yield [J]. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2018, 254: 191-201.

[3] Wang C, White P J, Li C J. Colonization and community structure of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in maize roots at different depths in the soil profile respond differently to phosphorus inputs on a long-term experimental site [J]. Mycorrhiza, 2016, 27(4): 1-13.

[4] Zhang J, Wang F, Che R X, et al. Precipitation shapes communities of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in Tibetan alpine steppe [J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6: 23488. doi: 10.1038/srep23488.

[5] Manoharan L, Rosenstock N P, Williams A, et al. Agricultural management practices influence AMF diversity and community composition with cascading effects on plant productivity [J]. Applied Soil Ecology, 2017, 115: 53-59.

[6] Liu H G, Wang Y J, Tang M. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi diversity associated with two halophytesL. andL. in Ningxia, China [J]. Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science, 2017, 63(6): 796-806.

[7] 张海波, 梁月明, 冯书珍, 等. 土壤类型和树种对根际土丛枝菌根真菌群落及其根系侵染率的影响[J]. 农业现代化研究, 2016, 37(1): 187-194. Zhang H B, Liang Y M, Feng S Z, et al. The effects of soil types and plant species on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi community and colonization in the rhizosphere [J]. Research of Agricultural Modernization, 2016, 37(1): 187-194.

[8] 蔡邦平, 陈俊愉, 张启翔, 等. 云南昆明梅花品种根围丛枝菌根真菌多样性研究[J]. 北京林业大学学报, 2013, 35(S1): 38-41. Cai B P, Chen J Y, Zhang Q X, et al. Diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi associated within Kunming, Yunnan, China [J]. Journal of Beijing Forestry University, 2013, 35(S1): 38-41.

[9] 任禛, 尹敏, 夏体渊, 等. 不同烤烟品种根系丛枝菌根真菌(AMF)群落结构和组成的差异分析[J]. 烟草科技, 2016, 49(3): 1-9. Ren Z, Yin M, Xia T Y, et al. Structure and composition difference of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi community in roots of flue-cured tobacco varieties [J]. Tobacco Science & Technology, 2016, 49(3): 1-9.

[10] 刘辉, 陈梦, 黄引娣, 等. 安徽茶区茶树丛枝菌根真菌多样性[J]. 应用生态学报, 2017, 28 (9): 2897-2906. Liu H, Chen M, Huang Y D, et al. Diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in the rhizosphere of tea plant from Anhui tea area, China [J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2017, 28(9): 2897-2906.

[11] 罗勇, 欧淑琼, 陈丝, 等. 基于RNA-Seq的茶树CsMYB生物信息学分析[J]. 分子植物育种, 2017, 15(6): 2119-2125. Luo Y, Ou S Q, Chen S, et al. Bioinformatics analysis of CsMYB in tea plant () based on RNA-seq [J]. Molecular Plant Breeding, 2017, 15(6): 2119-2125.

[12] 国家茶叶产业技术体系产业经济研究室. 2018年我国茶叶产销形势分析[J]. 中国茶叶, 2019, 41(4): 32-33. Industrial Economy Research Office of National Tea Industry Technology System. Analysis on the situation of tea production and marketing in China in 2018 [J]. China Tea, 2019, 41(4): 32-33.

[13] 吴丽莎, 王玉, 李敏, 等. 崂山茶区茶树根围AM真菌多样性[J]. 生物多样性, 2009, 17(5): 499-505. Wu L S, Wang Y, Li M, et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi diversity in the rhizosphere of tea plant () grown in Laoshan, Shandong [J]. Biodiversity Science, 2009, 17(5): 499-505.

[14] Singh S, Pandey A, Chaurasia B, et al. Diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi associated with the rhizosphere of tea growing in ‘natural’ and ‘cultivated’ ecosites [J]. Biology & Fertility of Soils, 2008, 44(3): 491-500.

[15] 查林. 安康茶叶产业发展战略研究[D]. 西安: 西安理工大学, 2006. Cha L. The discussion on the development strategy of Ankang tea industry [D]. Xi′an: Xi′an University of Technology, 2006.

[16] Phillips J M, Hayman D S. Improved procedures for clearing roots and staining parasitic and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid assement of infection [J]. Transations of the British Mycological Society, 1970, 55(1): 158-161.

[17] 柳洁, 肖斌, 王丽霞, 等. 盐胁迫下丛枝菌根(AM)对茶树生长及茶叶品质的影响[J]. 茶叶科学, 2013, 33(2):140-146. Liu J, Xiao B, Wang L X, et al. Influence of AM on the growth of tea plant and tea quality under salt stress [J]. Journal of Tea Science, 2013, 33(2): 140-146.

[18] 张春兰, 李苇洁, 姚红艳, 等. 不同猕猴桃品种根际AM真菌多样性与土壤养分相关性分析[J]. 果树学报, 2017, 34(3): 90-99. Zhang C L, Li W J, Yao H Y, et al. Correlation study on the diversity of the AM fungi and soil nutrients in the rhizosphere of different kiwifruit cultivars [J]. Journal of Fruit Science, 2017, 34(3): 90-99.

[19] Ianson D C, Allen M F. The effects of soil texture on extraction of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal spores from arid sites [J]. Mycologia, 1986, 78(2): 164-168.

[20] Schenck N C, Pérez Y. A manual for the identification of vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi [M]. Florida: University of Florida: 1990: 1-233.

[21] Redecker D, Schüßler A, Stockinger H. An evidence-based consensus for the classification of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Glomeromycota) [J]. Mycorrhiza, 2013, 23(7): 515-531.

[22] 王幼珊, 刘润进. 球囊菌门丛枝菌根真菌最新分类系统菌种名录[J]. 菌物学报, 2017, 36(7): 820-850. Wang Y S, Liu R J. A checklist of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in the recent taxonomic system of Glomeromycota [J]. Mycosystema, 2017, 36(7): 820-850.

[23] He F, Tang M, Zhong S L. Effects of soil and climatic factors on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in rhizosphere soil underin the Loess Plateau, China [J]. European Journal of Soil Science, 2016, 67(6): 847-856.

[24] Van der heijden M G A, Klironomos J N, Ursic M. Mycorrhizal fungal diversity determines plant biodiversity, ecosystem variability and productivity [J]. Nature, 1998, 396: 69-72.

[25] 盛敏, 唐明, 张峰峰, 等. 土壤因子对甘肃、宁夏和内蒙古盐碱土中AM真菌的影响[J]. 生物多样性, 2011, 19(1): 85-92. Sheng M, Tang M, Zhang F F, et al. Effect of soil factors on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in saline alkaline soils of Gansu, Inner Mongolia and Ningxia [J]. Biodiversity Science, 2011, 19(1): 85-92.

[26] Shannon C E, Weaver W. The mathematical theory of communication [M]. Urbana: Urbana university of Illinois Press. 1949, 85(2): 117.

[27] Pielou E C. The measurement of diversity in different types of biological collections [J]. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 1966, 13: 131-144.

[28] Pielou E C. Ecological Diversity [M]. New York: John Wiley and Sons Inc, 1975.

[29] 刘洁, 刘静, 金海如. 丛枝菌根真菌N代谢与C代谢研究进展[J]. 微生物学杂志, 2011, 31(6): 70-75. Liu J, Liu J, Jin H R. Advancement in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi’s N metabolic and C metabolic [J]. Journal of Microbiology, 2011, 31(6): 70-75.

[30] 郭绍霞, 刘润进. 不同品种牡丹对丛枝菌根真菌群落结构的影响[J]. 应用生态学报, 2010, 21(8): 1993-1997. Guo S X, Liu R J. Effects of different peony cultivars on community structure of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in rhizosphere soil [J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2010, 21(8): 1993-1997.

[31] Eom A H, Hartnett D C, Wilson G W T. Host plant species effects on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in tallgrass prairie [J]. Oecologia, 2000, 122: 435-444.

[32] 李岩, 焦惠, 徐丽娟, 等. AM真菌群落结构与功能研究进展[J]. 生态学报, 2010, 30(4): 1089-1096. Li Y, Jiao H, Xu L J, et al. Advances in the study of community structure and function of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi [J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2010, 30(4): 1089-1096.

[33] 张文驹, 戎俊, 韦朝领, 等. 栽培茶树的驯化起源与传播[J]. 生物多样性, 2018, 26(4): 357-372. Zhang W J, Rong J, Wei C L, et al. Domestication origin and spread of cultivated tea plants [J]. Biodiversity Science, 2018, 26(4): 357-372.

[34] 张成才, 刘园, 姜燕华, 等. SSR标记鉴定浙江省主要无性系茶树品种的研究[J]. 植物遗传资源学报, 2014, 15(5): 926-931. Zhang C C, Liu Y, Jiang Y H, et al. Application of SSR markers in cultivar identification of clonal tea plant in Zhejiang province, China [J]. Journal of Plant Genetic Resources, 2014, 15(5): 926-931.

[35] Chen Y S, Chen G, Fu X, e al. Phytochemical profiles and antioxidant activity of different varieties oftea (Jack) [J]. Journal of Agricultural & Food Chemistry, 2015, 63(1): 169-176.

[36] 吴丽莎, 王玉, 李敏, 等. 崂山茶区茶树根际丛枝菌根真菌调查[J]. 青岛农业大学学报: 自然科学版, 2009, 26(3): 171-173. Wu L S, Wang Y, Li M, et al. A survey of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in the rhizosphere ofin Laoshan [J]. Journal of Qingdao Agricultural University (Natural Science), 2009, 26(3): 171-173.

[37] 卢东升, 吴小芹. 豫南茶园VA菌根真菌种类研究[J]. 南京林业大学学报: 自然科学版, 2005, 29(3): 33-36. Lu D S, Wu X Q. Species of VAM fungi around tea roots in the southern area of Henan province [J]. Journal of Nanjing Forestry University (Natural Science Edition), 2005, 29(3): 33-36.

[38] 吴铁航, 郝文英, 林先贵, 等. 红壤中VA菌根真菌(球囊霉目)的种类和生态分布[J]. 真菌学报, 1995, 14(2): 81-85. Wu T H, Hao W Y, Lin X G, et al. VA mycorrhizal fungi (Glomales) and their ecological distribution in red soils [J]. Acta Mycologica Sinica, 1995, 14(2): 81-85.

[39] Shi Z Y, Gao S C, Wang F Y. Biodiversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in desert ecosystems [J]. Arid Zone Research, 2008, 25(6): 783-789.

[40] 贺学礼, 陈烝, 郭辉娟, 等. 荒漠柠条锦鸡儿AM真菌多样性[J]. 生态学报, 2012, 32(10): 3041-3049. He X L, Chen Z, Guo H J, et al. Diversity of arbuscular fungi in the rhizosphere ofKom. in desert zone [J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2012, 32(10): 3041-3049.

[41] 吕杰, 吕光辉, 马媛. 新疆艾比湖流域胡杨幼苗根际AM真菌多样性特征[J]. 林业科学, 2016, 52(4): 59-67. Lv J, Lv G H, Ma Y. Diversity of Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in the rhizosphere ofseedlings in Ebinur lake basin, Xinjiang [J]. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2016, 52(4): 59-67.

[42] 马忠莉. 松嫩草地丛枝菌根真菌孢子多样性对施肥的响应[D]. 长春: 东北师范大学, 2016. Ma Z L. Impacts of fertilization on the diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal spore in Songnen grassland [D]. Changchun: Northeast Normal University, 2016.

[43] 李华健, 贺学礼. 河北峰峰矿区构树AM真菌物种多样性及生态适应性[J]. 河北大学学报(自然科学版), 2019, 39(3): 278-287. Li H J, He X L. Species diversity and ecological adaptability of AM fungi infrom Fengfeng mining area in Hebei province [J]. Journal of Hebei University (Natural Science Edition), 2019, 39(3): 278-287.

[44] 贺学礼, 郭辉娟, 王银银, 等. 内蒙古农牧交错区沙蒿根围AM真菌物种多样性[J]. 河北大学学报(自然科学版), 2012, 32(5): 506-514. He X L, Guo H J, Wang Y Y, et al. Species diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in the rhizosphere ofin Inner Mongolia [J]. Journal of Hebei University (Natural Science Edition), 2012, 32(5): 506-514.

Analysis of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungal Community Structure in the Rhizosphere of Different Tea Cultivars

HE Fei, LI Donghua, BU Fan

School of Agriculture & Biotechnology, Ankang University, Ankang 725000, China

In order to enrich the arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungal germplasm resources of tea plants () in China, the community structure of AM fungi in the rhizosphere soil of different tea cultivars grown in Hanshuiyun tea garden of Ankang City, Shaanxi Province were analyzed. The results show that species richness, species and genera composition of AM fungi in the rhizosphere soil varied with tea cultivars. A total of six AM fungal species were isolated from the rhizosphere soil of Ziyang population. Likewise, five from Shancha 1, four from Longjing Changye, four from Longjing 43, and three species from Fuding Dabai. Soil collected from the rhizosphere of Longjing Changye had the highest spore density (3.57 spores per gram of dry soil), while the lowest spore density (1.10 spores per gram of dry soil) was found in the rhizosphere of Longjing 43. The highest Shannon-Wiener and Pielou evenness indices were found in the rhizosphere of Ziyang population (0.63 and 0.096), whereas the lowest values were observed in the rhizosphere of Longjing Changye (0.18 and 0.027). The maximum mycorrhizal colonization (29.5%) was found in the rhizosphere ofLongjing Changye, whereas the minimum value (15.8%) was observed in the rhizosphere of Fuding Dabai. The Sorenson’s similarity coefficient of AM fungal species composition among five tested tea cultivars ranged from 0.111 to 0.750, with the highest between Longjing Changye and Longjing 43, and the lowest between Fuding Dabai and Ziyang population. The results reveal obvious differences in AM fungal community composition among the five tea cultivars. The identified AM fungal resources in rhizosphere soil are of great significance for further screening, researching AM fungi agent, and promoting the development of tea industrialization.

AM fungi,, cultivar, community structure

S571.1,Q938

A

1000-369X(2020)03-319-09

2019-10-27

2019-12-24

陕西省科协青年人才托举计划项目(20170210)、陕西省教育厅自然科学专项研究计划项目(17JK0016)、安康学院高层次人才科研启动项目(2017AYQDZR06)、国家级大学生创新创业训练计划项目(201711397007、201711397006)

何斐,女,副教授,主要从事微生物资源利用方面的研究。hefei6000@163.com

投稿平台:http://cykk.cbpt.cnki.net