Resveratrol corrects aberrant splicing of RYR1 pre-mRNA and Ca2+ signal in myotonic dystrophy type 1 myotubes

2020-03-07MassimoSantoroRobertoPiacentiniAlessiaPernaEugeniaPisanoAnnaSeverinoAnnaModoniClaudioGrassiGabriellaSilvestri

Massimo Santoro , Roberto Piacentini , Alessia Perna Eugenia Pisano Anna Severino Anna Modoni Claudio Grassi Gabriella Silvestri

1 IRCCS Fondazione Don Carlo Gnocchi, Milan, Italy

2 Department of Neuroscience, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy

3 Department of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Sciences, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy

4 Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, Italy

Abstract Myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) is a spliceopathy related to the mis-splicing of several genes caused by sequestration of nuclear transcriptional RNA-binding factors from non-coding CUG repeats of DMPK pre-mRNAs. Dysregulation of ryanodine receptor 1 (RYR1), sarcoplasmatic/endoplasmatic Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) and α1S subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Cav1.1) is related to Ca2+ homeostasis and excitation-contraction coupling impairment. Though no pharmacological treatment for DM1 exists, aberrant splicing correction represents one major therapeutic target for this disease. Resveratrol (RES, 3,5,4′-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene) is a promising pharmacological tools for DM1 treatment for its ability to directly bind the DNA and RNA inf luencing gene expression and alternative splicing. Herein, we analyzed the therapeutic effects of RES in DM1 myotubes in a pilot study including cultured myotubes from two DM1 patients and two healthy controls. Our results indicated that RES treatment corrected the aberrant splicing of RYR1, and this event appeared associated with restoring of depolarization-induced Ca2+ release from RYR1 dependent on the electro-mechanical coupling between RYR1 and Cav1.1. Interestingly, immunoblotting studies showed that RES treatment was associated with a reduction in the levels of CUGBP Elav-like family member 1, while RYR1, Cav1.1 and SERCA1 protein levels were unchanged. Finally, RES treatment did not induce any major changes either in the amount of ribonuclear foci or sequestration of muscleblind-like splicing regulator 1. Overall, the results of this pilot study would support RES as an attractive compound for future clinical trials in DM1. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of IRCCS Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, Rome, Italy (rs9879/14) on May 20, 2014.

Key Words: alternative splicing; calcium homeostasis; CUG-BP1; foci; MBNL1; myotonic dystrophy type 1; myotubes; resveratrol

Introduction

Myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1, dystrophia myotonica, Steinert’s disease; OMIM 160900) is the most frequent form of adult muscular dystrophy, transmitted with autosomal dominant inheritance. DM1 is characterized by a multisystem involvement variably affecting other tissues and organs, besides the skeletal muscle (Harper, 2001; Machuca-Tzili et al., 2005).

The molecular defect associated with DM1 consists of a pathological expansion of a polymorphic cytosine—thymine—guanine (CTG)-repeat tract in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of dystrophia myotonica protein kinase gene (DMPK), a gene located on chromosome 19q13.2-q13.3 encoding for a serine-threonine kinase mainly expressed in the skeletal muscle and the heart (Fu et al., 1992; Harley et al., 1992; Mahadevan et al., 1992). While normal DMPK alleles contain 5 to 35 CTG repeats, pathological DM1 alleles harbor 50 to more than 1000 CTG repeats (Brook et al., 1992; Fu et al., 1992; Mahadevan et al., 1992).

The main recognized pathogenic mechanism in DM1 is a toxic gain of function of the pre-mRNA transcribed from the pathologically expanded allele assuming an aberrant “hairpin” conformation induced by the longer cytosine—uracil—guanine (CUG) stretch (Cho and Tapscott, 2007). This would indeed cause an accumulation of expanded RNA species within nuclear foci that would bind and eventually affect the function of specific RNA-binding transcription factors, named muscleblind-like proteins (MBNL) (Mankodi et al., 2001; Pascual et al., 2001). Moreover, increased steady state levels of other transcription factors, named CUG-binding protein 1 (CUG-BP1)/ETR-3-like factors (CELF) have been detected in DM1 tissues (Ladd et al., 2001). MBNL and CUG-BP/CELF antagonistically regulate the alternative splicing of many developmentally regulated genes, and evidence of their dysregulation in both DM1 transgenic models (Mankodi et al., 2000; Hao et al., 2008) and patients’ tissues (Ladd et al., 2001; Mankodi et al., 2001; Pascual et al., 2006; Osborne et al., 2009) is associated with diffuse mis-splicing, characterized by relatively increased levels of the embryonic vs. the adult mRNA isoforms.

Since DM1 is mainly a spliceopathy, various therapeutic approaches, such as RNA interference, ribozyme, small molecules, peptides, and antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) have been developed in order to reduce the expression levels, or antagonize the effects of the toxic expanded-CUG RNAs (Foff and Mahadevan, 2011; Klein et al., 2015). Specif ically, ASOs have shown particularly promising results to induce degradation of expanded RNAs by binding to the expanded CUG trait, consequently restoring normal activities of CELF or MBNL (Foff and Mahadevan, 2011; Klein et al., 2015) and eventually correct mis-splicing. Although ASO-therapy has been successfully tested in transgenic models of DM1, it requires further development before testing its effective benef it in DM1 patients.

Among pharmacological treatments, resveratrol (RES, 3,5,4′-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene) is a natural polyphenol with stilbenic structure found in red wine, grape skins and seeds, mulberries, blueberries, peanuts and rhubarb, that is receiving increased attention thanks to its ability to prevent or at least slow down the progression of several pathologies (Renaud and de Lorgeril, 1992; Di Castelnuovo et al., 2002). However, how this compound works has not been fully elucidated. It has been shown that RES modulates several intracellular signaling pathways, including activation of a Sirtuin class of NAD+-dependent deacetylases (Guarente and Picard, 2005), modulation of AMP-activated kinase and class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinase (Pozo-Guisado et al., 2004; Cantó and Auwerx, 2009). RES also has a neuroprotective effect, possibly related to its capacity to protect mitochondrial function and dynamics in the brain, tissue virtually dependent on oxidative metabolism, and thus particularly susceptible to the damage from increased oxidative stress and free radicals production (Jardim et al., 2017). Moreover, in experimental models of Alzheimer’s disease (Chen et al., 2019a, b), RES has been proven to play an anti-inf lammatory role both in microglia and astrocytes, as well as, to reduce accumulation of Aβ amyloid plaques and hyperphosphorylation of tau protein in the brain.

Of note, RES is able to modulate gene expression and alternative splicing, likely by a direct binding to DNA and RNA (Usha et al., 2005); in this regard, various studies have shown that RES enhances exon 7 inclusion of the survival motor neuron-2 pre-mRNA in model cell lines of spinal muscular atrophy (Sakla and Lorson, 2008; Markus et al., 2011) and corrects the aberrant splicing produced by a mutation in the GAA gene in fibroblasts from a patient with acid maltase deficiency (Dardis et al., 2014).

Concerning DM1, a single study from Takarada et al. (2015) clearly showed that RES was able to revert the aberrant splicing of the insulin receptor pre-mRNA in f ibroblasts from DM1 patients, and therefore it could be a potential therapeutic compound for DM1.

The skeletal muscle is one of the most affected tissues in DM1, therefore we decided to perform a preliminary study to test the effects of RES treatment in cultured myotubes derived from two DM1 patients on the aberrant splicing of sarcoplasmatic/endoplasmatic Ca2+-ATPase gene (SERCA), ryanodine receptor 1 gene (RYR1), and CACNA1S genes and the related changes in intracellular Ca2+homeostasis, previously documented by our group (Santoro et al., 2014).

For this purpose, DM1-derived muscle cell lines were assessed before and after exposure to RES using quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) studies about SERCA, RYR1, and CACNA1S genes expression, functional studies of intracellular calcium handling, RNA-f luorescence in situ hybridization immunof luorescence and western blot studies.

Material and Methods

Participants

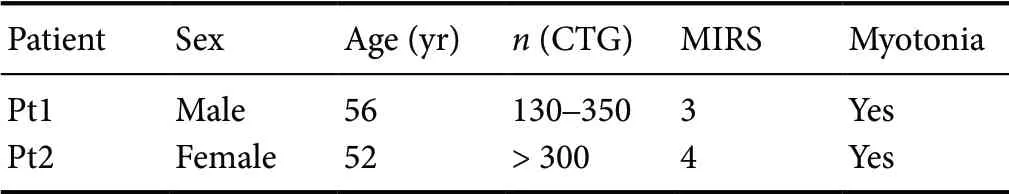

The study design was in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki and the guidelines approved by the Ethical Committee of IRCCS Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, Rome, Italy (rs9879/14) on May 20, 2014; muscle biopsies had been primarily performed for diagnostic purposes, following an informed consent stating that their stored muscle samples could have been also used for research purposes. Myoblasts were isolated from deltoid muscle biopsies of two adult-onset DM1 patients (Pt1 and Pt2) and two controls; the clinical (Mathieu et al. 2001) and genetic features of the two DM1 patients are reported in Table 1. Both controls (CTRL-1: male, 60 years of age; CTRL-2: male, 44 years of age) suffered from myalgias, had no electromyographic abnormalities or serum creatine kinase raise (normal range value: 30-170 IU/L), and their muscle morphological, immunohistochemical and biochemical studies were all normal.

Table 1 Clinical/molecular features of DM1 patients

Cell cultures

Primary muscle cells were isolated from muscle biopsies using the explantation re-explantation method as described in Askanas and Engel (1992). Myoblasts were maintained in a proliferative state up to the fourth passage by culturing them in a growth medium containing fetal bovine serum (15% v/v; Cambrex Bioscience, Walkersville, MD, USA) and a cocktail of growth factors. Multinucleated myotubes, generated by the fusion of mononucleated myoblasts, were obtained by replacing the growth medium with a new one (differentiation medium) containing 5% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and lacking growth factors and by culturing cells for 6 days (Broccolini et al., 2006).

Then myotubes were incubated for 24 hours in a medium containing different concentrations (0, 25, 50, 75, 100 and 200 μM) of RES (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) (Takarada et al. 2015) and harvested for further examination.

RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells using All-Prep DNA/RNA micro kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), in agreement with the manufacturer’s instructions. First strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using high capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR studies to assess alternative splicing of RYR1 ASII, CACNA1S and SERCA1 pre-mRNAs (exons 83, 29 and 22 respectively), were performed as previously described (Santoro et al., 2014). In brief, the reaction mix (total volume 25 μL), contained one half of the synthesized cDNA as template, 100 ng of either forward/reverse primers or MyTaq DNA polymerase (Bioline, Memphis, TN, USA). β-actin was amplified as internal standard and human embryonic myosin heavy chains (MHCe) was used as myogenic marker. For human SERCA1, RYR1 ASII, and CACNA1S PCR was repeated for 35 cycles with annealing temperature of 62°C. For β-actin and MHCe PCR was repeated for 25 cycles with annealing temperature of 55°C. RT-PCR products were resolved on 2% agarose gels. All the experiments were repeated in triplicate. Densitometric analysis was carried out by Image Lab software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Densitometric values were used to calculate the amount of exon inclusion percentage for each gene as it follows: exon inclusion percentage = amount of adult isoform/(amount of adult isoform + amount of neonatal isoform) × 100.

Ca2+ imaging

Ca2+imaging was performed as described in the studies of Santoro et al. (2014) and Piacentini et al. (2017). Myotubes cultured onto coverslips were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C with the Ca2+-sensitive dye Fluo-4 AM (Thermo Fisher Scientific), used at a concentration of 2.5 μM in Tyrode’s solution containing (in mM): 2 CaCl2, 150 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 (4-(2-hydroxyethil)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 10 glucose (pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). After Fluo-4 loading, fresh Tyrode’s solution was added to allow de-esterif ication of the dye. The coverslips were placed into a perfusion chamber placed on the stage of a DM IRE2 inverted microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) that was attached to a TCS-SP2 confocal laser scanning system (Leica Microsystems). Fluo-4 was excited at 488 nm and the f luorescence was collected between 500 and 535 nm. We recorded 30 frames (256 × 256 pixel resolution) for 60 seconds (at 0.5 Hz). Membrane depolarization (obtained by cell exposure to a modified Tyrode’s solution containing 54 mM NaCl and 100 mM KCl) or caffeine (20 mM in standard Tyrode’s solution) were used to induce intracellular Ca2+transients in myotubes. The following calibration formula was used for Fluo-4: [Ca2+]i=Kd× [(Ft- Fmin)/(Fmax- Ft)] (Takahashi et al., 1999; Santoro et al., 2014), in which Kdrepresents the dissociation constant (345 nM), Ftis the f luorescence measured in a region of interest at the generic time “t” and Fmaxand Fminare the maximum and minimum f luorescence values measured for each region of interest after the application of the ionophore 4-Br-A23187 (Fmax) and after application of 5 mM EGTA in Tyrode’s solution. Timeto-peak and peak amplitude of intracellular Ca2+transients were measured. The Ca2+response was also quantified by evaluating the mean Ca2+f lux under stimulation (nM/s). To evaluate the contribution of intracellular vs. extracellular Ca2+to the KCl-induced Ca2+transients, two consecutive applications of KCl-modified Tyrode’s solution were performed. The first one in the presence of 2 mM Ca2+and the second one delivered 5 minutes later in the virtual absence of Ca2+(Ca2+-free solution). In order to exclude that differences might derive to stochastic f luctuations of Ca2+transients we compared Ca2+response obtained in response to two consecutive stimuli (100 mM KCl) delivered at 5-minute interval. No significant differences were found (< 5%). Ca2+-imaging experiments were carried out at room temperature (RT: 23-25°C).

Myotubes RNA-f luorescence in situ hybridizationimmunof luorescence for MBNL1

Myotubes were f ixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at RT for 20 minutes, washed five times in 1 × PBS for 3 minutes and permeabilized in 0.2% TRITON-X-100/PBS for 5 minutes at RT.

After washing in 1× PBS, myotubes were incubated in pre-hybridization solution [40% formamide and 2× saline sodium citrate (SSC)] for 10 minutes at RT and then hybridized with a cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) probe (Santoro et al., 2010) for 2 hours at 37°C in 40% formamide, 2× SSC, 0.02% bovine serum albumin, 67 ng/μL yeast tRNA (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 2 mM vanadyl ribonucleoside complex (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA). Myotubes were first washed in 40% formamide/2× SSC at 37°C for 30 minutes and then incubated with blocking solution (3% bovine serum albumin and 0.2% Triton X-100 in 1× PBS) for 1 hour at RT. Then, myotubes were incubated with a primary monoclonal antibody raised against MBNL1, clone HL 1822 [3A4-1E9] (Santoro et al., 2010) (Sigma-Aldrich, 1:500 dilution) for 24 hours at 4°C, then washed f ive times in 1× PBS for 2 minutes and incubated with secondary antibody Texas-Red labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Cambridgeshire, UK) for 1 hour at RT.

Finally, myotubes were placed in 165 nM 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 10 minutes at RT, washed five times in 1× PBS, included with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), and examined using a confocal microscope (Nikon A1MP, Tokyo, Japan). Confocal stacks of images 1024 × 1024 pixels were acquired with a 60× objective (N.A. 1.4) plus a further 2× magnification. The number of nuclei with RNA foci and nuclei with MBNL1 was counted using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) in ten non-adjacent fields for each sample. An average of 400 nuclei was evaluated for each sample. The results were shown as the mean percentage of nuclei exhibiting RNA foci and MBNL1 on total nuclei.

Western blot analysis

Cultured myotubes were lysed in RIPA (Radio-ImmunoPrecipitation Assay) buffer containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors (HaltTMProtease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (100×); Thermo Fisher Scientific). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation (15,000 × g; 30 minutes, 4°C). Protein content was determined using the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with bovine serum albumin as standard protein. Protein lysates (35 μg) were separated on sodium dodecyl sulphate - polyAcrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDSPAGE) and transferred on polyvinylidene f luoride (PVDF) membrane. Membrane was probed overnight with following primary monoclonal antibodies: CUG-BP1 clone 3B1 (Aff inity Bioreagents, Golden, CO, USA; diluted 1:500) (Santoro et al., 2010), RYR1 clone 34C (Thermo Fisher Scientific; diluted 1:500) (Himori et al., 2017), α1S subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+channels gene (Cav1.1) clone 1A (Thermo Fisher Scientific; diluted 1:500) (Vanhoutte et al., 2016), SERCA1 clone VE121G9 (Thermo Fisher Scientific; diluted 1:500) (Toral-Ojeda et al., 2016). Proteins were normalized with β-actin monoclonal antibody clone C4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA; diluted 1:1,000) and monoclonal antibody against skeletal myosin clone MY-32 as myogenic marker (Sigma-Aldrich, diluted 1:100) (Santoro et al., 2010).

After incubation with goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated (1:3,000) (Bio-Rad Laboratories), blots were developed using the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL)-Western blotting analysis system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and then analyzed with Chemidoc XRS Image system and Image Lab 5.0 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Statistics

Means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) were used to represent data. In data normally distributed, assessed by GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) or Sigma Plot 14.0 (Systat Software Inc, San Jose, CA, USA) softwares, statistical significance was evaluated by Student’s t-test, or one-way analysis of variance; in the case of limited samples, a nonparametric analysis (Mann-Whitney U test). For small size data samples (less than 8 values), statistical significance was assessed by nonparametric Wilcoxon Signed Rank test. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

RES treatment corrects the alternative splicing of RYR1 in DM1 myotubes

In order to assess the effects of RES on the splicing pattern of RYR1, Cav1.1 and SERCA1 in cultured myotubes derived from DM1 patients and controls, we performed RT-PCR analysis after 24-hour treatment of cell cultures with different concentrations of RES (0, 25, 50, 75, 100 and 200 μM). In agreement with literature data (Takarada et al., 2015), RT-PCR showed that the exon percentage inclusion linearly increased until 100 μM and then plateaued (Figure 1A). This treatment did not alter the expression of MHCe gene, thus suggesting that RES would not affect myotube differentiation. We also performed RT-PCR analysis after 48-hour RES treatment (100 μM) of cultured myotubes, but we found no differences compared to the effects of a 24-hour treatment (Additional Figure 1).

Therefore, we chose 100 μM concentration and 24-hour RES treatment for our experimental plan.

In agreement with our previous findings (Santoro et al., 2014), untreated DM1 myotubes exhibited increased levels of the neonatal ASII (exon 83-) isoform of RYR1 mRNA compared to controls (Figure 1B).

Interestingly, DM1 myotubes exposed to RES treatment showed a significant increase in the relative amount of the adult ASII (exon 83+), rising from 60.5% to 84% (Figure 1C, left panel); also in control myotubes the percentage of inclusion of exon 83 raised from 89.7% to 97.8%, (Figure 1C, left panel). RT-PCR studies also conf irmed reduced levels of the “adult” Cav1.1 (exon 29+) mRNA in untreated DM1 vs. controls myotubes (Figure 1B, middle panel): in this case, RES treatment did not produce any significant changes on Cav1.1 mRNA alternative splicing either in DM1 or control myotubes (Figure 1C, middle panel).

RES treatment also did not change the aberrant expression of SERCA1 in DM1 myotubes (Figure 1B, right panel), while in control myotubes it raised levels of inclusion of SERCA1 ex 22 from 11% to 20% (Figure 1C, right panel).

RES treatment increases KCl-induced Ca2+ release from sarcoplasmic reticulum in DM1 myotubes

In parallel to molecular studies, we assessed whether RES treatment was able to revert the alteration of Ca2+handling machinery in DM1 myotubes.

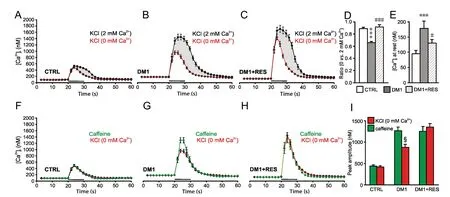

In basal condition, untreated control cells exhibited intracellular Ca2+concentration at rest of 95.4 ± 10.4 nM (n = 46; Figure 2A and E); application of 100 mM KCl in the presence of 2 mM external Ca2+induced intracellular Ca2+transients that peaked at 467.4 ± 30.7 nM over basal levels, with mean Ca2+f lux under stimulation of 230.8 ± 14.2 nM/s (Figure 2A).

The contribution to Ca2+transients from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) was estimated by repeating depolarizing stimulation in the absence of external Ca2+: the transients obtained under these conditions were similar to those obtained following stimulation in the presence of 20 mM caffeine (Figure 2F), supporting that the response to depolarizing stimuli obtained in the absence of external Ca2+indeed ref lects the activation of RYR1 on the SR. In the muscle cells, depolarization of the plasma membrane induces RYR1 activation through mechanical coupling with Cav1 channels, so the difference between transients during KCl stimulation in 2 vs. 0 mM external Ca2+(indicated as shaded areas in Figure 2A-C, or ratio in Figure 2D) likely indicates the Ca2+entry from extracellular medium depending on the late opening of Cav1 channels.

In comparison to control cells, DM1 myotubes exhibited increased Ca2+levels at rest (182.8 ± 21.8 [n = 38]; P = 3.9 × 10-4; Figure 2B and E). KCl stimulation induced intracellular Ca2+transients of significant greater amplitude (mean peak value: 1382.0 ± 88.3 nM over basal levels, P = 1.3 × 10-15; mean Ca2+f lux under stimulation: 660.6 ± 49.1 nM/s, P =1.1 × 10-12Figure 2B). Also, in DM1 compared to control myotubes KCl-induced Ca2+release from SR was lower than that induced by caffeine (-29% for peak and -21% for mean Ca2+f lux, P < 0.05 for both; Figure 2G).

Importantly, 24-hours RES treatment (100 μM) had a positive effect on the altered intracellular Ca2+handling in DM1 myotubes, while it did not determine any significant changes in control myotubes (Additional Figure 2).

In DM1 myotubes, RES treatment significantly increased the amount of KCl-induced Ca2+release from SR (for peak from 883.5 ± 62.0 nM to 1352.7 ± 85.8 nM, +53%; P = 1.5 × 10-5; for f lux from 346.5 ± 27.2 nM/s to 485.8 ± 31.6 nM/s, +40%; P = 1.2 × 10-3) (Figure 2C), with both values similar to those obtained after caffeine stimulation (Figure 2H). Noteworthy, the Ca2+release from SR following caffeine stimulation was not modif ied by RES treatment (Figure 2I), suggesting that RES would influence the opening of RYR channels under KCl stimulation rather than proper RYR channel function.

RES treatment also significantly corrected the increased time-to-peak of Ca2+transients (3.8 ± 0.3, 6.5 ± 0.5 and 4.2 ± 0.3 seconds, for CTRL, DM1 and DM1+RES, respectively; P = 3.6 × 10-5CTRL vs. DM1, P = 1.1 × 10-3for DM1 vs. DM1 + RES). Finally, RES exposure partially reverted the increase in basal Ca2+levels (127.2 ± 12.3 nM, P = 0.03 vs. untreated DM1 myotubes), and this effect was accompanied with a significantly faster restoration of [Ca2+]iafter transient elevation (time constant of decay: 4.7 ± 0.1 seconds in CTRL myotubes. 5.5 ± 0.2 seconds in DM1 vs. 4.8 ± 0.2 seconds in DM1 + RES, P = 0.03).

On the other hand, RES treatment did not influence the quota of Ca2+coming from late activation of Cav1 channels (f luxes: 460.0 ± 62.2 nM/s in untreated cells vs. 464.3 ± 43.3 nM/s in RES-treated cells).

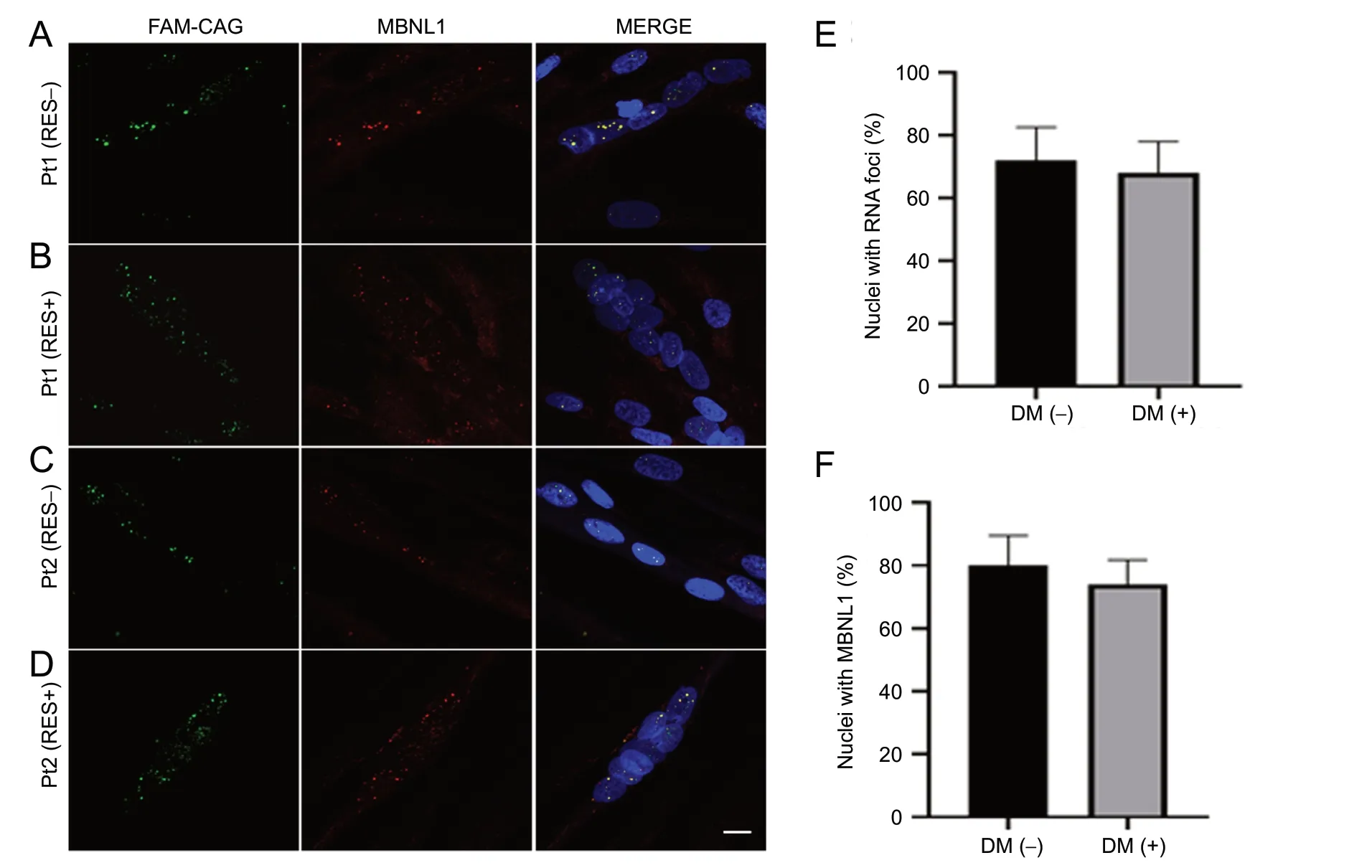

Nuclear foci and MBNL1 protein localization are not affected in DM1 myotubes treated with RES

According to literature data, the sequestration of MBNL proteins at the ribonuclear foci mainly accounts for the aberrant splicing occurring in DM1 and DM2 tissues (Miller et al., 2000; Mankodi et al., 2003). By combined RNA-f luorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) immunofluorescence analysis with CAG probe and MBNL1 antibody, we assessed if RES treatment would also induce any changes in the features of ribonuclear foci and/or their co-localization with MBNL1 in DM1 myotubes.

By RNA-FISH we did not document any gross quantitative changes of nuclear foci in RES-treated vs. untreated DM1 myotubes (Figure 3A-D, left panel), with respective cell lines showing an average percentage of nuclei containing RNA foci- of 72% and 68%, respectively (Figure 3E).

Also, immunof luorescence analysis revealed similar co-localization of MBNL1 with the ribonuclear foci in DM1 myotubes before (Figure 3A, C, and F) and after (Figure 3B, D, and F) RES treatment.

As expected, control myotubes showed no nuclear foci and a normal intracellular distribution of MBNL1 (Additional Figure 3).

RES treatment reduces CUG-BP1 protein levels and leaves unaltered RYR1, Cav1.1 and SERCA1 in DM1 myotubes

In order to investigate whether RES treatment could influence the steady-state levels of CUG-BP1, RYR1, Cav1.1 and SERCA1 proteins in myotubes, we first assessed their amount by western blot analysis in untreated myotubes of DM1 patients (Pt1 and Pt2) and controls (CTRL-1 and CTRL-2).

In agreement with previous studies (Savkur et al., 2001), untreated DM1 myotubes showed higher steady-state levels of CUG-BP1 compared to controls (Figure 4A). In both controls and DM1 cell lines, RES treatment was associated with a reduction in the CUG-BP1 levels (Figure 4B) (21% in DM1 myotubes, 15% in control. Statistical analysis showed that the reduction was significant only for comparison of DM1 vs. DM1 + RES (P = 0.04).

The steady-state levels of RYR1 resulted lower in untreated DM1 vs. control myotubes, while the levels of Cav1.1 and SERCA1 proteins resulted similar. RES treatment did not produce any obvious changes either on RYR1, Cav1.1 or SERCA1 protein levels (Figure 4B).

Discussion

Current therapeutic strategies in DM1 are mainly addressing removal of the toxic expanded CUG pre-mRNAs in order to release MBNL proteins, CUG-binding transcription factors whose sequestration into ribonuclear foci produce dysregulation of alternative splicing in DM1 tissues (Magaña and Cisneros, 2011). Gene therapy using morpholino modif ied, RNA-based ASOs have been shown to correct missplicing events in DM1 cell cultures and animal models (Foff and Mahadevan, 2011; Magaña and Cisneros, 2011; Klein et al., 2015). Nevertheless, early trials in DM1 patients have failed, mainly due to their insufficient intracellular delivery, so further pharmaceutical studies are on-going to overcome this issue.

The assessment of safe compounds able to modulate alternative splicing could represent another worthwhile therapeutic strategy in DM1: among these substances, RES, a natural polyphenol with various recognized therapeutic properties (Vang et al., 2011; Vang, 2013), when tested on human-derived cell cultures was able to modulate the alternative splicing of various pre-mRNAs (Sakla and Lorson, 2008; Markus et al., 2011; Dardis et al., 2014). Most importantly, RES reverts the aberrant splicing of insulin receptor gene (INSR) enhancing exon 11 inclusion in HeLa cells and in f ibroblasts of DM1 patients (Takarada et al., 2015).

Based on these premises, we have decided to perform a pilot study on two DM1 and two control muscle cell lines, in order to test the effects of RES on the aberrant splicing of RYR1, CACNA1S and SERCA RNAs and the consequent perturbation of intracellular Ca2+handling, likely to be involved in the pathogenesis of muscle degeneration in DM1 (Kimura et al., 2005; Tuluc and Flucher, 2011; Botta et al., 2013; Santoro et al., 2014).

Figure 1 SERCA1, RYR1 and Cav1.1 splice variant analysis in RES-treated DM1 myotubes.

Results from this preliminary study show that RES treatment is able to partially rescue the aberrant splicing only for RYR1 pre-mRNA in DM1 muscle cell lines, with enhanced exon 83 inclusion, whereas splicing of CACNA1S and SERCA do not show any significant changes. Supporting our findings, a recent study conducted on DM1 transgenic mice has shown that RES treatment partially corrected the aberrant splicing of RYR1, TNNT3 and muscle-specif ic chloride channel gene (CLCN1), but not of SERCA1 (Ravel-Chapuis et al., 2018).

Figure 2 DM1 myotubes exhibits altered intracellular Ca2+ transients at rest and KCl-induced release of Ca2+ from sarcoplasmic reticulum that are corrected by RES treatment.

Figure 3 RNA-f luorescence in situ hybridization and immunof luorescence studies for MBNL1 on patients (Pt) 1 and Pt2 myotubes.

Figure 4 Western blot analysis of CUG-BP1, RYR1, and Cav1.1 proteins.

In parallel to changes on RYR1 expression, calcium imaging data in RES-treated DM1 myotubes documented a significant increase of the amount of Ca2+released from RYR1 after depolarizing stimulation, similar to the effects obtained after caffeine stimulation which directly activates RYR1, the latter being unmodif ied by RES treatment.

The effect of RES on intracellular calcium handling in DM1 myotubes might be explained by different hypotheses. First, DM1 myotubes exhibit an altered membrane potential at rest, change that in turn inf luences the activation of DHPRs under KCl stimulation determining an incomplete opening of RYR1, and RES might restore this situation. In such case, however, an altered rest membrane potential should also affect late activation of Cav1 channels, so RES would also be expected to modify the amount of Ca2+entry from extracellular medium, but our experimental data showed that this did not occur in RES-treated DM1 myotubes.

Alternatively, RES-driven enhancing of exon 83 of RYR1 pre-mRNA could restore a correct interaction between dihydropyridine and ryanodine receptors. Indeed, in the skeletal muscle, the physical interaction between Cav1.1 channels and RYR1, required for EC coupling, is dependent on the geometrical alignments between these two proteins. Experimental data suggest that α1S II-III loop, α1S III-IV loop and the β1a carboxyl terminus of Cav1.1 channels are involved in these interactions with multiple regions of RYR1 (Leong and MacLennan, 1998; Sheridan et al., 2006; Rebbeck et al., 2011). The exclusion of ASII leads to the absence of an amino acid sequence (Val3865-Asn3870) in a modulatory region of RYR1 that contains a protein binding motif (Futatsugi et al., 1995), and we previously suggested that this could affect the interaction between the Cav1.1 and RYR1 proteins, ultimately influencing intracellular [Ca2+] levels in DM1 myotubes (Santoro et al., 2014).

The hypothesis that a partial correction of RYR1 aberrant splicing induced by RES could restore a correct interaction between Cav1.1 and RYR1 is supported by the following results obtained in RES -treated vs. -untreated DM1 myotubes: i) RES treatment did not change the amount of Ca2+mobilized following caffeine stimulus (causing direct activation of RYR1), supporting that RES does not directly inf luence proper RYR1 function and/or its expression; and ii) RES treatment significantly increased the intracellular Ca2+response to a depolarizing stimulus in the absence of external Ca2+, while it had no effect on the amount of Ca2+due to late activation of Cav1.

On the other hand, our functional data revealed that RES treatment does not have any effects on increased KCl-induced intracellular Ca2+levels in DM1 myotubes, likely because this alteration would mostly depend on increased Ca2+entry through Cav1 activation (that is not modulated by RES), rather than from altered E-C coupling.

How RES would modulate alternative splicing in DM1 tissues is still unclear; literature data supported that RES might modulate either the levels or the activation of splicing factors such as ASF/SF2, HuR (Long and Caceres, 2009; Markus et al., 2011), KHSRP and hnRNPA1 (Puppo et al., 2016; Moshiri et al., 2017), but the underlying molecular mechanisms have yet to be determined.

Concerning DM1, our results of combined RNA-FISH/MBNL1 immunof luorescence studies in DM1 myotubes suggest that the enhanced exon 83 RYR1 inclusion produced by RES would not be mediated by changes either in the number of nuclear foci or in the related MBNL sequestration. Indeed, MBNL1 is more involved in the alternative splicing regulation of Cav1.1 and SERCA1 (Hino et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2012), and accordingly we did not f ind obvious changes in the aberrant splicing of these two genes in DM1 myotubes exposed to RES treatment.

We also investigated whether RES treatment could influence the steady-state levels of CUG-BP1, another other transcription factor strongly involved in the pathogenesis of mis-splicing in DM1 tissues as found to be overexpressed in DM1 tissues. Of note, CUG-BP1 steady-state levels by WB were reduced in DM1 myotubes after RES treatment, and another study conducted on an animal model and on patients with skeletal muscle atrophy (Tang et al., 2015) showed that CUG-BP1 directly regulates RYR1 alternative splicing.

Taken together, these data suggest that RES could modulate RYR1 exon 83 inclusion in DM1 myotubes by producing changes in the steady-state levels of CUG-BP1.

Ca2+-imaging data in DM1 myotubes showed that the amplitude of transients induced by caffeine did not change after RES treatment, and accordingly Western blot did not document any significant changes in the steady-state levels of RYR1 protein in DM1 cell lines. However, we underline that the limited resolution of WB analysis cannot allow the distinction between fetal and neonatal RYR1 isoforms, since both are high molecular weight variants differing by only few amino acids.

On the other hand, the lower steady state RYR1 levels detected in untreated DM1 vs. control myotubes could be related to a lower stability of the fetal RYR1 isoform in adult tissues. Nevertheless, as our study included only two DM1 cell lines, further studies on additional DM1-derived myotubes are needed to conf irm this observation.

Finally, Cav1.1 and SERCA1 proteins showed similar levels before and after RES treatment both in DM1 and control myotubes. However, we found that RES partially normalizes resting Ca2+, along with a faster restoration of [Ca2+]iafter transient elevation, thus suggesting that RES increases the activity of SERCA. Again, future studies on DM1 myotubes will help to clarify this apparent discrepancy and to further validate the results of this research.

Of course this represents a pilot study, whose main limitation concerns the small sample size of DM1 patients-derived cell lines. Nevertheless, the results are promising, and deserve to be conf irmed on further DM1 myotubes, although their availability is currently limited, as muscle biopsy is not required anymore to diagnose DM1.

Systemic administration of RES in DM1 transgenic mice, particularly those overexpressing CUG-BP1, will be helpful to assess the therapeutic effects of RES, on the various multisystem disease manifestations of DM1. Overall, our findings, together with previous literature support RES as a candidate molecule for upcoming clinical therapeutic trials in DM1, to potentially improve muscle rehabilitation and therefore the quality of life in these patients. Further studies are needed to def ine if this compound would be useful to face the complex DM1 pathogenesis with its multisystem involvement.

Acknowledgments:We are grateful to Glen W. Mc Williams, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor of Urology, Columbia University and Mount Sinai School of Medicine, USA for revising the English form of the manuscript.

Author contributions:Project and experiments were designed by MS and RP. Experiments and data analysis were performed by MS, RP, AP, EP, AS and AM. Manuscript was written and revised by MS, RP, CG and GS. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest:All the authors deny any financial support and conf lict of interest regarding this research activity.

Financial support:This work was supported by grants from Università Cattolica and Italian Ministry of Scientific Research (grant number D1-2016; to GS).

Institutional review board statement:Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of IRCCS Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, Rome, Italy (rs9879/14) on May 20, 2014. All participants signed a statement of informed consent.

Declaration of participant consent:The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate participant consent forms. In the forms, the participants have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The participants understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity.

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Data sharing statement:Datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Open peer reviewers:Lorenzo Di Cesare Mannelli, University of Florence, Italy; Endre Pal, Pecsi Tudomanyegyetem Altalanos Orvostudomanyi Kar, Hungary.

Additional f iles:

Additional file 1: Open peer review reports 1 and 2.

Additional Figure 1: Analysis of RYR1, SERCA1 and Cav1.1 alternative splicing.

Additional Figure 2: Intracellular Ca2+transients evoked in control myotubes are not affected by resveratrol.

Additional Figure 3: RNA-f luorescence in situ hybridization and immunof lorescence studies for MBNL1 on CTRL-1 myotubes.

杂志排行

中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Recovery of an injured ascending reticular activating system with recovery from a minimally conscious state to normal consciousness in a stroke patient: a diffusion tensor tractography study

- Interleukin-18 levels in the hippocampus and behavior of adult rat offspring exposed to prenatal restraint stress during early and late pregnancy

- EndoN treatment allows neuroblasts to leave the rostral migratory stream and migrate towards a lesion within the prefrontal cortex of rats

- Role of neurotrophic factors in enhancing linear axonal growth of ganglionic sensory neurons in vitro

- A double-network hydrogel for the dynamic compression of the lumbar nerve root

- The Akt/glycogen synthase kinase-3β pathway participates in the neuroprotective effect of interleukin-4 against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury