EndoN treatment allows neuroblasts to leave the rostral migratory stream and migrate towards a lesion within the prefrontal cortex of rats

2020-03-07JannisGundelachMichaelKoch

Jannis Gundelach, Michael Koch

Department of Neuropharmacology, Center for Cognitive Sciences, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany

Abstract The binding properties of neural cell adhesion molecule are modulated by a polysialic acid moiety. This plays an important role in the migration of adult born neuroblasts from their area of origin, the subventricular zone, towards the olfactory bulb. Polysialisation increases the migration speed of the cells and helps to prevent the neuroblasts from leaving their migration route, the rostral migratory stream. Here, we evaluated the potential of intraventricular application of endoneuraminidase-N, an enzyme that specif ically cleaves polysialic acid from neural cell adhesion molecule, in a rat model for structural prefrontal cortex damage. As expected, endoneuraminidase-N caused the rostral migratory stream to become wider, with a less uniform cellular orientation. Furthermore, endoneuraminidase-N treatment caused the neuroblasts to leave the rostral migratory stream and migrate towards the lesioned tissue. Despite the neuroblasts not being differentiated into neurons after a survival time of three weeks, this technique provides a solid animal model for future work on the migration and differentiation of relocated neuroblasts and might provide a basis for a future endogenous stem cell-based therapy for structural brain damage. The experiments were approved by the local animal care committee (522-27-11/02-00, 115; Senatorin für Wissenschaft, Gesundheit und Verbraucherschutz, Bremen, Germany) on February 10, 2016.

Key Words: endogenous stem cells; endoneuraminidase; neural cell adhesion molecule; neuroblast migration; olfactory bulb; polisialic acid; structural brain damage; subventricular zone

Introduction

Although our understanding of the function of the brain and the constant threat of damage, either due to neurodegenerative diseases or trauma, constantly grows, so far no neurorestorative treatment for structural brain damage has been developed. Whilst the mammalian brain constantly produces new neurons in certain areas, these cells follow predetermined migration patterns and are generally not available for repair of forebrain lesions.

Immature neurons, so called neuroblasts, are generated by asymmetrical division of neuronal stem cells in the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the brain (Curtis et al., 2011). From there they follow migratory cues through a def ined route, the rostral migratory stream (RMS), through the ventral forebrain towards the olfactory bulb (OB) (Jankovski et al., 1998; Kirschenbaum et al., 1999; García-Marqués et al., 2010). The tube of surrounding glia cells together with blood vessels build up a physical boundary, separating the RMS from the adjacent tissue and hindering the migrating neuroblasts from deviating from their physiological path (Whitman et al., 2009). On route, the neuroblasts interact with each other and form longitudinal aggregates, so called chains, which allows for a faster migration (Wichterle et al., 1997; Nam et al., 2007). Once the neuroblasts reach the OB, they separate from each other and migrate radially into the OB where they differentiate into granule and periglomerular cells (Mouret et al., 2009).

The polysialic acid (PSA) moiety is a posttranslational modification of the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM), prominently found in migrating neuroblasts, consisting of long, negatively charged chains of sialic acid (Finne, 1982; Finne et al., 1983). The rapid reduction in NCAM-mediated interaction between cells is crucial for dynamic adhesive processes especially during development (Hildebrandt et al., 2007) but also in axon pathfinding of motor neurons (Landmesser et al., 1990; Tang et al., 1992, 1994), synaptic plasticity (Muller et al., 1996) and hippocampal learning processes (Becker et al., 1996; Senkov et al., 2006). Furthermore, PSANCAM plays a major role in the migration of postnatally generated neuroblasts. Both an NCAM-mutation as well as the enzymatic removal of PSA by endoneuraminidase-N (endoN) lead to a reduction of RMS migration whereas radial migration of individual cells remains unaffected (Ono et al., 1994; Hu et al., 1996; Chazal et al., 2000). In both cases not only fewer cells enter the RMS and the OB, also the structure of the RMS changes towards a widened and less organized form. A more recent study revealed a major difference between NCAM and PSA deficit: Apart from the aforementioned reduction of RMS migration, the enzymatic removal of PSA led to a dispersal of neuroblasts from the RMS into the surrounding tissue (Battista and Rutishauser, 2010).

In the present study, we utilized this effect to allow postnatally generated neuroblasts to leave their physiological route, the RMS, and test if these neuroblasts then migrate towards an excitotoxic brain lesion in the neighboring prefrontal cortex.

Materials and Methods

Animals

This study was conducted on 33 adult (4.4 to 6.9 months) male Wistar rats (Charles River, Sulzfeld, Germany). The animals were kept under standard housing conditions (12-hour light/dark cycle, lights on at 7 a.m., water ad libitum, standard lab chow 12 g/rat per day) in groups of 4-6 animals per cage. The experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institute of Health ethical guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals for experiments and were approved by the local animal care committee (522-27-11/02-00, 115; Senatorin für Wissenschaft, Gesundheit und Verbraucherschutz, Bremen, Germany) on February 10, 2016.

Treatment

In a first stereotactic surgery, the animals were lesioned by a bilateral microinjection of ibotenic acid (Cayman Chemical Company, MI, USA; 6.7 mg/mL saline; injection volume of 0.4 μL at 0.3 μL/min infusion rate) into the medial prefrontal cortex (rostrocaudal +3.2 mm; lateral ±0.5 mm; ventrodorsal -4.4 mm, relative to bregma (Paxinos and Watson, 1998); Figure 1A). Control animals received a vehicle injection (0.4 μL of phosphate buffered saline, PBS). In a second surgery 5 days later endoN (0.5 μL, provided by Prof. Dr. Gerardy-Schahn, Institute for Cellular Chemistry, Hannover Medical School) was injected into the lateral ventricle (rostrocaudal -0.8 mm; lateral ±1.4 mm; ventrodorsal -6.0 mm, relative to bregma) bilaterally at an infusion rate of 0.15 μL/min. The enzyme endoN was applied at concentrations of 50 μg/mL (endoN group), 500 μg/mL (endoN-Hi group) or vehicle only (control group; Figure 1B). The resulting experimental groups were: vehicle/vehicle (C/C): n = 6; vehicle/endoN (C/E): n = 7; ibotenic acid/vehicle (L/C): n = 6; ibotenic acid/endoN (L/E): n = 8; ibotenic acid/high dose of endoN (L/E-Hi): n = 3. One of the L/E animals was excluded from further analysis, since the lesion could not be identif ied unequivocally.

The surgical procedures were performed under isof lurane anesthesia (CP-Pharma, Germany; vaporizer in circle system), and regulated to keep the spontaneous breathing rate of the animals at 40-60 breaths per minute. The injection cannulae (custom made from 30 G hypodermal stainless steel cannulae) were left at the given coordinates for 3 minutes before and after each injection. Subsequently, the trepanations were closed with bone wax (SMI AG, Belgium). Before suturing the skin, an antiseptic ointment (Betaisodona, Mundipharma, Germany) and a local anaesthetic (Xylocain 2%, AstraZeneca GmbH, Wedel, Germany) were applied.

Three weeks after the second surgery, the animals were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (200 mg/kg body weight at a concentration of 20 mg/mL PBS; Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) and transcardially perfused with cold PBS, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde solution.

The efficacy of the used endoN to eliminate PSA-NCAM from rat brain tissue was tested ex vivo beforehand. Single brain sections of perfused, otherwise untreated animals were incubated in a lower concentrated endoN solution (1 μg/mL) for 24 hours. These sections were then stained for PSA-NCAM following the protocol described below.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical double staining against the neuroblast marker doublecortin (DCX) and the marker for adult neurons, neuronal nuclei (NeuN) was performed on free f loating 40 μm sagittal brain cryosections (distance between sections: 120 μm). After blocking in 10% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) and 0.05% Triton-X for 1 hour at room temperature, the primary antibodies (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany, rabbit anti-NeuN (RRID: AB_10807945), 1:1000 and Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) doublecortin antibody (C-18) (RRID: AB_2088494), 1:1000 in the blocking solution) were allowed to incubate for 24 hours at 4°C. The sections were then rinsed in PBS and blocked in 10% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH) before incubation with the secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (RRID: AB_10989100), 1:2000 and Santa Cruz biotinylated donkey anti-Goat (RRID: AB_631726), 1:1000)) for 24 hours at 4°C. Again, the sections were rinsed and blocked, then the streptavidin conjugated dye (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Streptavidin-Alexa Fluor 568 (RRID: AB_2337250), 1:2000, in the blocking solution) was allowed to incubate for another 24 hours at room temperature. Before mounting and coverslipping (f luorescent mounting medium, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), the specimens were counterstained for circa 10 minutes in 0.9% w/v Sudan black (Acros Organics, Belgium) in 70% ethanol.

Previously endoN-incubated brain sections of untreated animals (see above) were stained for polysialylated-neural cell adhesion molecule (PSA-NCAM). The procedure followed the protocol described above, but the anti-NeuN antibody was exchanged for an antibody against PSA-NCAM (mab-735 (RRID: AB_2619682), provided by Prof. Dr. Gerardy-Schahn, Institute for Cellular Chemistry, Hannover Medical School), followed by a f luorescent coupled secondary antibody (JacksonImmunoResearch, Alexa Fluor 488 Aff iniPureGoat anti Mouse IgG (H+L) (RRID: AB_2338840)).

Image acquisition and analysis

Images were acquired on a fluorescent microscope (Axioscope 100, Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany) equipped with a monochrome digital camera (Spot, Visitron Systems GmbH, Puhlheim, Germany). Further image processing was performed in the ImageJ (NIH, USA. Version 1.49 h) (Schneider et al., 2012; Schindelin et al., 2015) based software FIJI (Schindelin et al., 2012). The overview images were then stitched in Microsoft Image composition editor (Microsoft Cooperation, Redmond, WA, USA, version 1.4.4.0) using the planar motion 1 (rigid scale) setting. High-magnification images were taken as z-stacks (10 images each) and combined in FIJI, using the “extended depth of field” macro (Wheeler) with a radius set to 5 px.

The lesions and RMS were examined hemisphere-wise. If the structure of interest could not be identified without doubt in the available brain sections, the hemisphere was excluded from analysis. This resulted in a reduced sample size in the RMS measurements.

DCX-positive cells were counted on the sagittal slices approximately 1.4 mm lateral to bregma by an observer blind to the treatment. The area of the lesion was measured in the same brain section.

The width of the RMS was measured at three different positions (Figure 1A).

All statistical analyses were conducted in SigmaStat (version 3.5 for Windows, Systat Software Inc., Richmond CA, USA). Cell counts were analyzed using a Kruskal-Wallis oneway analysis of variance (ANOVA) on ranks followed by all pairwise multiple comparisons (Dunn’s method). The RMS width was first logarithmically transformed, and then analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by pairwise multiple comparisons (Student-Newman-Keuls test).

Results

Ibotenic acid-induced lesions

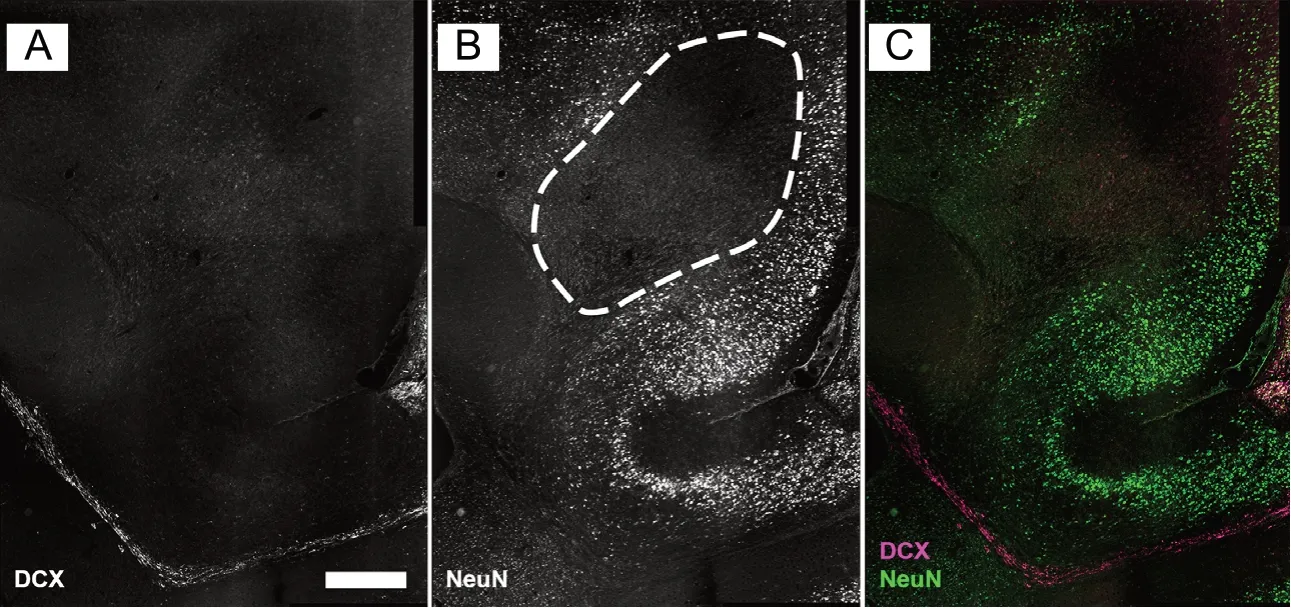

The injection of ibotenic acid into the prefrontal cortex reliably induced lesions of the tissue. A brain volume including parts of the prelimbic and infralimbic cortex and in some cases parts of the cingulate cortex, area 1 and the dorsal peduncular cortex was observed to be free of NeuN-positive cells 3 weeks after the injections (Figure 2). We discussed the glial response to identically induced lesions elsewhere (Gundelach and Koch, 2018). The vehicle injection caused no detectable lesion apart from the cannula channel.

EndoN eliminates all PSA-NCAM ex vivo

The effectiveness of endoN was tested by incubating free f loating brain sections for 24 hours in 1 μg/mL endoN and then stained for PSA-NCAM. Control sections showed a diffuse background staining throughout the whole tissue [compare Bonfanti (2006)], and a distinct staining in the cells of the RMS (Figure 3A), the SVZ and hippocampus. In contrast, endoN-treated sections were virtually free of PSANCAM staining (Figure 3B).

Morphology of the RMS

As reported before (Ono et al., 1994; Hu et al., 1996; Battista and Rutishauser, 2010), endoN application caused the RMS to become wider with a less organized structure. In order to evaluate the effectiveness of the endoN-treatment, the width of the RMS was assessed.

Under physiological conditions, the RMS shows a coherent path of DCX-positive cells, many of which form elongated aggregates (Figure 4A and C). The application of endoN caused the RMS to become wider and more diffuse with a less uniform orientation of cells (Figure 4B and D). Also the formation of cell chains was reduced. A change of general migration direction from the RMS towards the excitotoxic lesion was observed in the L/E and L/E-Hi groups (Figure 4E), but not the controls (Figure 4C and D).

The measured RMS thickness (Figure 5) varied between subjects and was probably also inf luenced by the exact anatomical position of the brain section examined. However, in the caudal and rostral portion of the RMS, the diameter measured in the microscope differed significantly between treatment groups (ANOVA after logarithmic (ln) transformation, caudal P = 0.004; rostral P = 0.006). As revealed by the all pairwise post-hoc test (Student-Newman-Keuls), all endoN-treated groups differed from the C/C group significantly, both in the caudal (C/E (n = 11) vs. C/C (n = 8): P = 0.021; L/E (n = 10) vs. C/C: P = 0.019; L/E-Hi (n = 5) vs. C/C: P = 0.013) and the rostral (C/E (n = 9) vs. C/C (n = 10): P = 0.016; L/E (n = 7) vs. C/C: P = 0.030; L/E-Hi (n = 3) vs. C/C: P = 0.012) measurement point. In neither of both positions, the L/C group did not differ significantly from the C/C group (caudal: P = 0.359, n = 9; rostral P = 0.072, n = 8). In the ventral portion of the RMS, no significant differences were found (P = 0.163; C/C: n = 7; C/E: n = 12; L/C: n = 8; L/E: n = 9; L/E-Hi: n = 5).

Taken together, all endoN-treatments caused the RMS to become wider than the control treatment in the caudal and rostral, but not the ventral part of the RMS. The lesioned animals that did not receive an endoN injection (L/C group) did not show a significantly wider RMS in any position.

Two different populations of cells are positive for DCX

As discussed elsewhere (Kunze et al., 2015; Gundelach and Koch, 2018), two different types of cells positive for the marker DCX are found in brain lesions. In short, one type shows strong immunoreactivity and the typical, polar morphology of neuroblasts (Martinez-Molina et al., 2011). The other cell type that is also positive for the astrocytic marker GFAP, has a larger soma with multiple processes and is only weakly stained by the DCX antibody [compare Gundelach and Koch (2018)]. Taking these pronounced differences in staining intensity and cell morphology into account, DCX provides a reliable marker for neuroblasts.

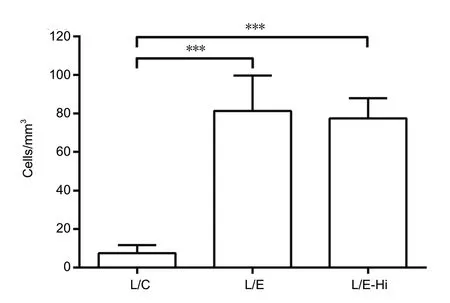

Cells migrate into the lesion after endoN treatment

EndoN treatment allowed neuroblasts to migrate into the mPFC lesions (Figure 6D-I). Both doses of endoN resulted in a significantly higher number of DCX-positive neuroblasts within the lesion compared to lesioned and vehicle injected controls (Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks; H = 13.440; 2 degrees of freedom, P < 0.001; Figures 6A-C and 7). However, the effects of the doses were not different from each other with respect to the number of cells. Neuroblasts were found in the lesions of 71.4 % of the endoN-treated animals (n = 14 hemispheres) and 100 % of the endoN-Hi group (n = 6 hemispheres). 25% of the control lesions (n = 12 hemispheres) showed comparably low numbers of neuroblasts.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that the known effect of endoN to foster the dispersion of SVZ-neuroblasts from the RMS, allows these cells to migrate towards a lesion in the vicinity of the RMS. After injection of two different doses of the enzyme into the lateral ventricle of lesioned rats, significantly more DCX-positive neuroblasts were found within the lesioned tissue, compared to control animals.

Effect of endoN treatment

The ex vivo experiment demonstrated the enzymatic efficacy of the endoN utilized in this study, since all detectable PSANCAM was removed from free floating rat brain sections even at a lower concentration than used in vivo. Furthermore, the morphological changes of the RMS following an in vivo application of endoN are in line with previous findings (Battista and Rutishauser, 2010): Our measurements indicate that the enzymatic treatment led to a widening of the caudal and rostral RMS compared to controls. Furthermore, the structure of the RMS of endoN-treated animals was less organized and the typical chains of neuroblasts were observed less frequently.

Effects of the excitotoxic lesion and endoN on migrating neuroblasts

Under physiological conditions, neuroblasts are guided by chemoattractive and —repulsive signals towards their target locations [reviewed in Sun et al. (2010); Leong and Turnley (2011)]. However, also damaged tissue in the brain attracts migrating neuroblasts over a shorter distance. This has been described in studies of spontaneous neuroblast migration towards damaged tissue (Jin et al., 2003; Lee, 2006; Kunze et al., 2015) and is further supported by our earlier work (Gundelach and Koch, 2018), in which the chemoattractive substance laminin was used to redirect neuroblasts from the RMS. After the cells had left the artificial migration path, they kept on migrating in a now non-uniformly oriented manner throughout the brain lesion.

Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of PSA-NCAM for the chain migration of neuroblasts tangentially through the RMS towards the olfactory bulb, whereas the radial migration of single cells seems to be largely unaffected by the lack of PSA-NCAM (Ono et al., 1994; Hu et al., 1996). However, a more recent study found PSA overexpression to enhance the sensitivity of single neural precursor cells towards various migratory cues (Glaser et al., 2007).

We demonstrated that SVZ-derived cells, once they have left the RMS, migrate towards a brain lesion due to the previous removal of PSA-NCAM. In contrast, removal of PSA from NCAM in unlesioned animals only causes neuroblasts to leave the RMS but not migrate far away from their physiological route (Battista and Rutishauser, 2010). Earlier studies have identif ied several mechanisms involved in the guidance of individual neuronal precursor cells. However, our results suggest that the PSA-regulated PI3K receptor pathway that is involved in guidance of grafted embryonic stem cell-derived neuronal precursors (Glaser et al., 2007), is not essentially involved here, since the endoN treatment would downregulate this mechanism. Therefore, other guidance cues, such as chemokines (Belmadani, 2006; Robin et al., 2006; Yan et al., 2007), might play a major role under the given experimental conditions.

Fate of relocated cells

In our present study, no cells both immunoreactive for DCX and NeuN were found within the brain lesions. This stands in contrast to our previous work on relocated neuroblasts in which a small number of cells showed morphological and immunocytochemical signs of differentiation (Gundelach and Koch, 2018). It is possible that the relocated cells need more than the provided survival time of three weeks to migrate and differentiate. However, under physiological conditions most neuroblasts develop into OB-neurons within 15-30 days after proliferation (Petreanu and Alvarez-Buylla, 2002). Interestingly, endoN-based removal of PSA from NCAM has been demonstrated to promote cell differentiation of neuroblastoma cells (Seidenfaden et al., 2003) as well as SVZ-neuroblasts: After demyelination of the corpus callosum, endoN-treatment not only enhances migration of SVZ cells towards the lesion, but also causes the cells to differentiate towards a oligodendroglial cell type (Decker et al., 2002). Furthermore, neuroblasts that do not leave the SVZ after endoN-treatment were found to differentiate towards a neuronal morphology and express tyrosine hydroxylase, resembling OB cells (Petridis et al., 2004). In vitro experiments revealed that this effect is cell-cell contact dependent and can be reduced by anti-NCAM antibodies. However, tyrosine hydroxylase expression was not detected in the cultured cells (Petridis et al., 2004). Together these findings indicate that the fate of neuroblasts can be largely influenced by the interaction with the surrounding tissue. Physiologically, these influences on proliferating and migrating neuroblasts are prevented by the polysialated NCAM within the cell membranes. Once the cells reach their position within the OB, PSA-NCAM is downregulated (Rousselot et al., 1995), thus a similar, contact-dependent fate determination is conceivable. In our experiments a large volume of the surrounding tissue was lesioned, thus reducing the potential of interaction between neuroblasts and intact nerve cells. In addition, the neuroblasts were found to spread within the lesion, which makes an interaction between these cells and an endoN-induced cell differentiation unlikely. Taken together, this raises the question if a smaller lesion would allow for maturation of the relocated neuroblasts. However, it remains to be determined, if such focal lesions would release a sufficient concentration of signal molecules to guide the neuroblasts from the RMS towards the damaged tissue.

EndoN induces redirection of neuroblasts as an animal model for future research

The presented method of endoN-induced redirection of SVZ-derived neuroblasts provides a reliable and relatively undemanding animal model for further studies on endogenous neuroblasts in the context of brain lesions. Specific blockage of receptors could elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the guidance of individually migrating neuroblasts. Additionally, the model allows for testing of other candidate molecules (Belmadani, 2006; Robin et al., 2006; Yan et al., 2007) on their attractive and repulsive potential on neuroblasts in vivo.

Furthermore, the method allows studies on manipulation of the long term fate of relocated neuroblasts. First, the pharmacological inhibition of programmed cell death (Gascon et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2007) could increase the number of neuroblasts within the lesion. Furthermore, we found no signs of newly differentiated neuronal cells within the lesions three weeks after the endoN-treatment, which means the previously described differentiation stimulating effects of endoN (Petridis et al., 2004) are ineffective under the given experimental conditions. However, there are molecules known to promote differentiation of neuronal precursor cells, such as brain derived neurotrophic factor (Ahmed et al., 1995), epidermal growth factor (Reynolds and Weiss, 1992), insulin-like growth factor-I (Arsenijevic and Weiss, 1998), and leukemia inhibitory factor (Memberg and Hall, 1995). Application of these substances to relocated neuro-blasts might enable their differentiation and integration into the surrounding neuronal tissue eventually.

Figure 1 Schematic representation of the approximate position of the lesion and the RMS (A) and timeline of the experiments (B).

Figure 2 Ibotenic acid induced lesion within the forebrain.

Figure 4 Effects of treatments on RMS morphology.

Figure 3 Effect of endoN treatment on PSA-NCAM staining tested ex vivo.

Figure 6 Neuroblasts within the lesion of endoN-treated animals.

Figure 5 Diameter of the RMS measured at three different locations (see Figure 1).

Figure 7 Doublecortin-positive neuroblasts found within the lesion.

The present study concentrated on SVZ derived neuroblasts in male rats and the general mechanisms of neurogenesis and neuroblasts migration exist in both sexes. However, steroid hormones have been found to influence the rate of SVZ proliferation (Farinetti et al., 2015) and thereby lead to a sexual dimorphism of the olfactory bulb of Wistar rats (Peretto et al., 2001). In fact, the inf luence of sex steroids on adult neurogenesis in the SVZ is a matter of ongoing discussion and seems to differ at various developmental stages and between rodent strains (Ponti et al., 2018). Further experiments are necessary to determine sex differences in the endoN-based mechanism of neuroblasts relocation.

Moreover, the rate of proliferation has been reported to decline with age in rodents (Kuhn et al., 1996; Tropepe et al., 1997; Shook et al., 2012), which would likely result in a lower number of redirected neuroblasts in older animals under otherwise identical experimental conditions. The impact of this reduced rate of neurogenesis could easily be tested using cohorts of rats of different ages. Finally, it would be interesting if, and to what extent an age effect could be counteracted by the pharmacological stimulation of SVZ-proliferation (O’Keeffe et al., 2009; Koyama et al., 2013; Santos et al., 2014).

Potential for the development of a clinical application

The idea of a clinical application of endoN-induced neuroblast migration towards a brain lesion is appealing since the limited differentiation potential of these cells makes them safer than, for example, embryonic stem cells while avoiding the associated ethical problems. Furthermore, the surgical procedure is relatively simple and minimal invasive. However, there are a number of differences between the animal model and humans that have to be considered.

First, the aforementioned age-dependent decline in neurogenesis is probably more pronounced in humans. The recent literature even debates the general existence of neurogenesis in adults humans (Boldrini et al., 2018; Kempermann et al., 2018; Sorrells et al., 2018). Second, human neuroblasts migration differs from the animal model, as the migration through the RMS towards the OB seems to be limited to early childhood (Sanai et al., 2011; Bergmann et al., 2012). Instead, in the adult human neuroblasts migrate from the SVZ towards the adjacent striatum (Ernst et al., 2014). Therefore, it remains unclear, if an endoN-treatment would have comparable inf luence on the migration capabilities of adult neuroblasts.

Conclusion

The endoN-based technique enables migration of neuroblasts into a brain lesion and utilizes the migratory cues probably released by the lesion to guide the neuroblasts to their target. Therefore, it requires low surgical effort. However, the neuroblasts do not seem to differentiate within the lesion spontaneously. Furthermore, it is unclear to what extent neurogenesis declines after infancy in humans. It remains to be determined if endoN proves useful for the development of a clinical treatment for structural brain damage.

Acknowledgments:We thank Prof. Rita Gerardy-Schahn and Prof. Herbert Hildebrandt for generously providing EndoN and the antibody against PSA-NCAM as well as valuable information about the substances. Furthermore, we thank Maja Brandt for excellent technical assistance. This study is part of the PhD-Thesis of Jannis Gundelach submitted to the University of Bremen.

Author contributions:Study concept and design: JG and MK; experimental implementation, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, and manuscript preparation: JG; manuscript review: MK. Both authors approved the final version of the paper.

Conf licts of interest:None declared.

Financial support:None.

Institutional review board statement:The animal experiments were approved by the local animal care committee (522-27-11/02-00, 115; Senatorin für Wissenschaft, Gesundheit und Verbraucherschutz, Bremen, Germany) on February 10, 2016.

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by both authors before publication.

Data sharing statement:Datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

杂志排行

中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Recovery of an injured ascending reticular activating system with recovery from a minimally conscious state to normal consciousness in a stroke patient: a diffusion tensor tractography study

- Resveratrol corrects aberrant splicing of RYR1 pre-mRNA and Ca2+ signal in myotonic dystrophy type 1 myotubes

- Interleukin-18 levels in the hippocampus and behavior of adult rat offspring exposed to prenatal restraint stress during early and late pregnancy

- Role of neurotrophic factors in enhancing linear axonal growth of ganglionic sensory neurons in vitro

- A double-network hydrogel for the dynamic compression of the lumbar nerve root

- The Akt/glycogen synthase kinase-3β pathway participates in the neuroprotective effect of interleukin-4 against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury