Interleukin-18 levels in the hippocampus and behavior of adult rat offspring exposed to prenatal restraint stress during early and late pregnancy

2020-03-07MoXianChenQiangLiuShuChengLeiLeiAiJinLinRanWeiTomyHuiQiLiLiJuanAoPakSham

Mo-Xian Chen , Qiang Liu , Shu Cheng, Lei Lei, Ai-Jin Lin Ran Wei, Tomy C.K. Hui, Qi Li, , Li-Juan Ao , Pak C. Sham,

1 School of Rehabilitation, Kunming Medical University, Kunming, Yunnan Province, China

2 Department of Surgery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China

3 Department of Rehabilitation, China Resources & WISCO General Hospital, Wuhan, Hubei Province, China

4 Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, the Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, Sichuan Province, China

5 Institute of Basic Medicine, Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences, Jinan, Shandong Province, China

6 Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China

7 State Key Laboratory of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China

8 Centre for Genomic Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China

Abstract Exposure to maternal stress during prenatal life is associated with an increased risk of neuropsychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety, in offspring. It has also been increasingly observed that prenatal stress alters the phenotype of offspring via immunological mechanisms and that immunological dysfunction, such as elevated interleukin-18 levels, has been reported in cultures of microglia. Prenatal restraint stress (PRS) in rats permits direct experimental investigation of the link between prenatal stress and adverse outcomes. However, the majority of studies have focused on the consequences of PRS delivered in the second half of pregnancy, while the effects of early prenatal stress have rarely been examined. Therefore, pregnant rats were subjected to PRS during early/middle and late gestation (days 8-14 and 15-21, respectively). PRS comprised restraint in a round plastic transparent cylinder under bright light (6500 lx) three times per day for 45 minutes. Differences in interleukin-18 expression in the hippocampus and in behavior were compared between offspring rats and control rats on postnatal day 75. We found that adult male offspring exposed to PRS during their late prenatal periods had higher levels of anxiety-related behavior and depression than control rats, and both male and female offspring exhibited higher levels of depression-related behavior, impaired recognition memory and diminished exploration of novel objects. Moreover, an elevated level of interleukin-18 was observed in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus of male and female early- and late-PRS offspring rats. The results indicate that PRS can cause anxiety and depression-related behaviors in adult offspring and affect the expression of interleukin-18 in the hippocampus. Thus, behavior and the molecular biology of the brain are affected by the timing of PRS exposure and the sex of the offspring. All experiments were approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee at Kunming Medical University, China (approval No. KMMU2019074) in January 2019.

Key Words: behavior; depression; dorsal hippocampus; interleukin-18; prenatal restraint stress; recognition memory; sex; ventral hippocampus

Introduction

Exposure to maternal stress during prenatal life is associated with an increased risk of neuropsychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety (Zhang et al., 2016). Prenatal restraint stress (PRS) in rats permits direct experimental in-vestigation of the link between prenatal stress and adverse outcomes that is not possible in human studies (Schmitz et al., 2002; Marrocco et al., 2012, 2014). Offspring that had been exposed to PRS exhibit features that mimic depression and anxiety (Bowman et al., 2004; Zagron and Weinstock, 2006; Zuena et al., 2008) and atypical immunological characteristics, such as abnormal natural killer cytotoxicity (Klein and Rager, 1995) and higher levels of cytokines (O’Mahony et al., 2006). However, the majority of studies have focused on the consequences of PRS delivered in the second half of pregnancy, while the effects of early prenatal stress have rarely been examined. Studies that have examined the consequences of stress during early pregnancy in rats have observed a detrimental effect on postnatal outcomes. For example, exposure to PRS on gestation days (GD) 0—10 has been reported to impair performance on the Morris water maze (Modir et al., 2014). Another study has shown that offspring exposed to PRS on GD 5.5-17.5 do not adapt to stress in postnatal life (Miyagawa et al., 2015). However, despite these initial data, a direct comparison of the effects of PRS during ‘early’ and ‘late’ gestation has not been undertaken. Doing so is important because evidence now suggests that the timing of adverse events in prenatal life strongly inf luences the nature and severity of postnatal pathology in the exposed off-spring (Ellman et al., 2008; Buynitsky and Mostofsky, 2009; Li et al., 2009b, 2010; McAlonan et al., 2010). In the present study, we evaluated the effects of PRS in either early/middle (GD 8-14) or late (GD 15-21) gestation in rats.

Additionally, because preclinical and clinical studies have linked immune dysregulation caused by fetal stress to adverse postnatal outcomes (Coussons-Read et al., 2007; Veru et al., 2014), we examined the effects of PRS on postnatal levels of interleukin-18 (IL-18). IL-18, a cytokine belonging to the IL-1 superfamily, induces interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) production via an inf lammatory response (Lee et al., 2017). Recent studies have demonstrated that IL-18 is elevated in the blood and hippocampus of patients with stress-induced depression, and the administration of antibiotics can attenuate stress-induced elevation of IL-18 in the brain (You et al., 2011; Maslanik et al., 2012; Prossin et al., 2016). Moreover, the hippocampus plays a critical role in learning and memory (Tsukerman, 2016; Leeson et al., 2019; Lima and Gomes-Leal, 2019) and also may have a role in the pathophysiology of major depression disorder (MacQueen and Frodl, 2011). Additionally, the hippocampus is sensitive to early-life environment (Pleasure et al., 2000), particularly maternal stress (Barzegar et al., 2015). Thus, in the present study, we measured IL-18 levels in the hippocampus of rats after PRS using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and a western blot assay.

Material and Methods

Animals

Specific pathogen-free male (n = 45) and female (n = 15) Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Department of Kunming Medical University, China (license No. SYXK (Dian) K2015-0002). The rats were mated overnight, and GD 0 was determined through vaginal smear and the presence of spermatozoids. Pregnant female SD rats were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle (light from 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m.) at constant room temperature (23°C) and humidity (60%) with free access to food and water. All experiments were performed with the approval of the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee at the Kunming Medical University, China (ethical approval number: KMMU2019074) in January 2019.

PRS procedure

We divided pregnant rats into two groups: PRS on early/middle GD 8-14 (early-PRS) and PRS on late GD 15-21 (late-PRS). Pregnant female rats were individually restrained in a round plastic transparent cylinder (diameter: 7 cm; length: 19 cm) three times per day (9:00 a.m., 1:00 p.m., and 5:00 p.m.) under bright light (6500 lx) for 45 minutes, as described previously (Louvart et al., 2005). A control group of female rats was left undisturbed throughout the pregnancies. Because prenatal stress has distinct effects on male and female offspring (Weinstock et al., 1992; Glover and Hill, 2012), we included both male and female offspring in our study.

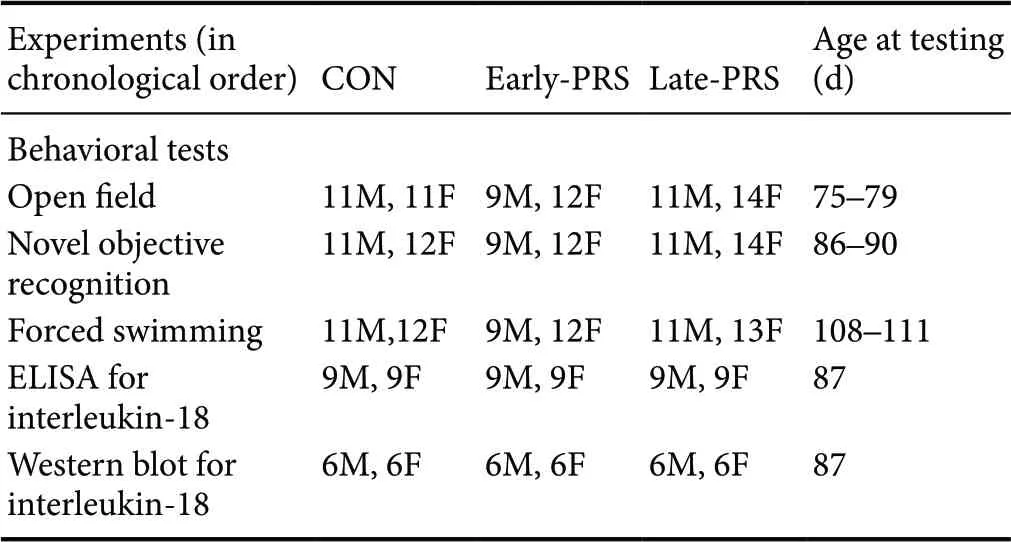

Fifteen mated females were fed and randomly assigned to early-PRS, late-PRS, and control groups. All the resulting offspring (early-PRS: n = 39; late-PRS: n = 43; control: n = 41) were weaned and left undisturbed until the experiments were initiated in adulthood (postnatal day 75). Some of the offspring were subjected to behavioral tests and the others were used for the IL-18 assay analysis. There was at least 1 week of rest between different behavioral tests. Owing to the loss of data, one Open Field test and one Forced Swim Test could not be included in the analysis. The level of IL-18 in the hippocampus was quantified post-mortem. A detailed summary of the numbers, sex, and age of rats used across the experiments and the order of each experiment is provided in Table 1.

Behavioral tests

Open Field test

The Open Field test measures levels of activity. The open field (100 cm × 100 cm × 40 cm) had a central area (50 cm × 50 cm) and was peripherally def ined. All animals were tested between 8:00 a.m. and 6:00 p.m. First, the rats were gently placed in the center of the open field and allowed to explore undisturbed for 30 minutes (Pähkla et al., 1996). A video camera f ixed on the ceiling 1.5 m above the f loor captured and recorded the images. The distance that the rat traveled in the field and the time spent in the central area were analyzed by an EthoVision tracking system (Version XT 7.0; Netherlands Noldus Company, Wageningen, the Netherlands).

Table 1 Sample size in each experimental group

Novel Object Recognition test

The Novel Object Recognition (NOR) test is a test of memory. The test was conducted in a black cage (100 cm × 100 cm × 50 cm) and had three steps: training, resting, and testing (Bevins and Besheer, 2006; Zhou et al., 2019). Before the training began, two identical sample objects were placed in the corners of the same side of the cage. A rat was then placed at the midpoint of the wall opposite the objects and left for 10 minutes of training in which they could freely explore the cage and the objects. After training, the rats had 1 hour to rest. In the test phase, one of the sample objects was replaced by a novel object, and the rat was returned to the cage for 5 minutes and again allowed to freely explore the objects. All animals were tested between 8:00 a.m. and 6:00 p.m. A video camera f ixed on the ceiling 1.5 m above the f loor captured and recorded the images. The NOR task is a widely used test for investigating the ability to remember objects (Antunes and Biala, 2012; Grayson et al., 2015). Rats naturally prefer to explore new objects over familiar ones. Thus, when a rat spends more time exploring a new object in the presence of a familiar one, we can infer that the rat remembers the familiar object (Leger et al., 2013; Stragier et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2016). We calculated the time the rat spent interacting with the sample and novel objects (when its nose was in contact with the object or directed at the object at a distance ≤ 2 cm). We also def ined and recorded a discrimination index (DI); exploration patterns allow statistical discrimination between the novel and familiar objects. The DI was calculated by subtracting the exploration time devoted to the familiar object (TF) from that devoted to the novel object (TN), then dividing this value by the total exploration time DI = [(TN - TF)/(TN + TF)] × 100. This result can vary between +1 and -1, where a positive score indicates more time spent with the novel object, a negative score indicates more time spent with the familiar object and a zero score indicates a null preference (Wei et al., 2016).

Forced Swim Test

The Forced Swim Test (FST) measures signs of depression. Rats were individually placed in clear plastic cylinders (diameter: 30 cm; height: 50 cm) containing water (25 ± 2°C) that was 30 cm deep, which prevented them from sup-porting themselves by touching the bottom with their paws (Bevins and Besheer, 2006; Bilge et al., 2008). On the first day, rats were placed in the plastic cylinders for 15 minutes. Water in the tank was changed after each animal had been subjected to the test. The rats were then removed from the tank, carefully dried with paper towel and returned to their home cages. All animals were tested between 8:00 a.m. and 6:00 p.m. On the following day, the movements of the rat were captured by a camera positioned in front of the water tanks for 5 minutes and the percentage of time that each animal spent being immobile was calculated using EthoVision XT 7.0.

Protein levels of IL-18 in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus analyzed by ELISA and western blot assay

Sandwich ELISA was used to detect IL-18 levels in the hippocampus of four randomly selected rats each from the control and PRS groups (total 12 rats) after each had completed their behavioral testing. Rats were rapidly sacrif iced after anesthesia with chloral hydrate via intra-peritoneal injection. Dorsal and ventral hippocampuses were dissected above ice and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until use. Samples were weighed, placed into the lysis buffer (Ripa buffer), and homogenized. Samples were then centrifuged at 12,000 r/min for 20 minutes, and the supernatants were aliquoted and frozen at -80°C until assays were performed. IL-18 protein levels were determined using the IL-18 ELISA kit (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for detecting rat IL-18 in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The limit of IL-18 detection was 4 pg/mL. Samples and standards were duplicated and run in the same assay.

Western blot was also used to detect IL-18 levels in the hippocampus at a different level. Brain samples were collected using the same methods as ELISA. The concentration of protein was quantified by a bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA kit, Thermo scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and all the samples were equalized to 20 μg. Procedures for the western blot followed those described previously (Li et al., 2009a, 2015). The primary antibodies to β-actin (mouse, 1:1000, Proteintech, Proteintech Group, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and IL-18 (rabbit, 1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) were incubated in the antibody dilution buffer with gentle agitation overnight at 4°C, then incubated with the secondary antibody, horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG(H+L) (1:2000, Proteintech, Proteintech Group, Inc.) and horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG(H+L) (1:2000, Proteintech, Proteintech Group, Inc.) for 1 hour at room temperature. Finally, protein bands were analyzed and quantif ied using the gel image processing system ImageJ (Rawak Software, Stuttgart, Germany) and normalized with β-actin concentrations.

Statistical analysis

All statistics were carried out using SPSS software version 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data were analyzed by using a 3 Group (control, early-PRS or late-PRS) × 2 Sex (male or female) two-way analysis of variance or a 3 Group (control, early-PRS, and late-PRS) × 6 Time (5-minute bins) twoway analysis of variance for the open-field test. Fisher’s least significant difference post-hoc comparisons were carried out whenever a main effect or interaction attained statistical significance. When there was a significant Group and Sex interaction or main effect of Sex, male and female data were considered separately. The threshold for statistical significance was P < 0.05.

Results

Behavioral performance of adult rats exposed to PRS

Open Field test

The distance moved in 5-minute bins in the open field was taken as a measure of intrasession habituation and anxiety-related behaviors were measured as time spent in the central area (Bolivar, 2009). Total distance traveled in each 5-minute bin and time spent in the central area is shown in Figure 1. We found a significant main effect of Sex on the total distance moved (F(1,372)= 37.086, P < 0.0001), with females moving more than males. The dataset was therefore split by sex for further analysis. The total distance moved was analyzed using a 3 (Group: control, early-PRS, and late-PRS) × 6 (Time: 5-minute bins) two-way analysis of variance for each sex, separately. In male rats, we observed a significant main effect of Group (F(2,168)= 8.856, P < 0.0001) and Time (F(5,168)= 60.25, P < 0.0001), but no interaction between the two. Post-hoc comparisons revealed that late-PRS rats were hypoactive compared with both control (P < 0.0001) and early-PRS rats (P < 0.01) (Figure 1). In female rats, we found a significant main effect of Time (F(5,204)= 105.668, P < 0.0001), indicating that animals moved less as the session continued. However, we did not f ind a significant effect of Group (F(2,204)= 2.474, P = 0.087) or any Group × Time interaction. Thus, only male rats exposed to PRS in late pregnancy showed lower than normal exploration in the open field.

We also observed a significant main effect of Sex on the time spent in the central area (F(1,372)= 7.449, P = 0.007). The dataset was therefore split by sex for further analysis. In male rats, we found a significant main effect of Group on the time spent in the central area (F(2,30)= 5.361, P = 0.011). Post-hoc comparisons revealed that Late-PRS rats spent significantly less time in the center area compared with controls (P < 0.01); while the Late-PRS and Early-PRS groups differed on this measure, the difference was non-significant (P = 0.088) (Figure 1). Time spent in the central area did not differ by Group in female rats (Figure 1). Thus, only male rats exposed to PRS in late pregnancy spent less time than normal in the central area of the open field.

NOR

The NOR is widely used to assess memory ability in rats. The DI represents the degree of discrimination between novel and familiar objects. The DI is expressed as the ratio of total time spent exploring both objects, making it possible to adjust for any differences in total exploration time in the novel environment (Broadbent et al., 2009). We found a significant main effect of Group on the DI (F(2,63)= 8.956, P < 0.0001), but no main effect of Sex or significant Group × Sex interaction. Post-hoc testing confirmed that both early-PRS (P < 0.01) and late-PRS (P < 0.001) groups had a significantly lower DI compared with controls (Figure 2). Thus, NOR was impaired in rats of both sexes exposed to early or late PRS.

FST

The FST is often used as a method of measuring the efficiency of antidepressants in rodents (Cryan et al., 2005). During the FST, the presence of immobility ref lects a state of behavioral despair and depression. We found a significant main effect of Sex on the FST immobility index (F(1,62)= 181.155, P < 0.0001) but there was non-significant Group × Sex interaction on this index (F(2,62)= 2.573, P = 0.084). The dataset was thus split by sex for further analysis. In male rats, we observed a significant group difference in the duration of immobility (F(2,30)= 5.949, P < 0.01). Post-hoc testing conf irmed that early-PRS (P < 0.05) and late-PRS (P < 0.01) groups were significantly more immobile than the control group (Figure 3). In female rats, a marginally significant group difference was observed on the immobility measure (F(2,36)= 3.127, P = 0.057). Post-hoc testing showed that the Late-PRS group was significantly more immobile than the control group (P < 0.05) in female rats (Figure 3). Thus, on the FST, male offspring exposed to early or late PRS exhibited significant depression-like behavior, while female offspring showed significant depression-like behavior only after exposure to late PRS.

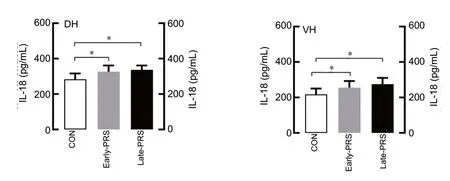

IL-18 levels in dorsal and ventral hippocampus of adult rats exposed to PRS

IL-18 levels in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus were abnormal in rats who were exposed to PRS. ELISA revealed a significant main effect of Group on IL-18 levels in the ventral and dorsal hippocampus (ventral hippocampus: F(2,53)= 12.525, P < 0.0001; dorsal hippocampus: F(2,53)= 15.144, P < 0.0001). No effects of Sex or an interaction between Sex and Group were observed. Post-hoc testing conf irmed that both early-PRS and late-PRS groups had significantly higher IL-18 levels in their dorsal hippocampus and ventral hippocampus compared with the control group (P < 0.05) (Figure 4).

Western blot analysis indicated similar results. We found a significant main effect of Group on IL-18 levels (dorsal hippocampus: F(2,12)= 13.34, P = 0.001; ventral hippocampus: F(2,12)= 19.14, P < 0.001). Again, there were no effects of Sex or any interaction between Sex and Group. Post-hoc comparisons showed that IL-18 levels in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus were both significantly higher in the early-PRS and late-PRS groups than in the control group (P < 0.05) (Figure 5).

Discussion

Figure 1 Intrasession habituation during the Open Field test in adult rats exposed to prenatal restraint stress.

Figure 2 Discrimination index (DI) for novel object recognition in adult rats exposed to prenatal restraint stress.

Figure 3 Total time that adult rats exposed to prenatal restraint stress spent being immobile during the forced swimming test.

Figure 4 IL-18 levels in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus of adult rats exposed to prenatal restraint stress (ELISA analysis).

Figure 5 Expression level of IL-18 in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus of adult rats exposed to prenatal restraint stress (Western blot analysis).

The present study demonstrated that the timing of exposure to stress in prenatal life inf luences the postnatal outcome in rodent offspring. We found that adult rodent offspring (male and female) exposed to PRS during late gestation had higher levels of depression-related behavior, impaired object memory, and elevated levels of IL-18 in the hippocampus. However, the effects of early PRS were more limited. Although early PRS impaired object memory and increased IL-18 levels in the hippocampuses of both male and female offspring, it only induced depression-related behavior in male offspring. Our results suggest that late-gestation exposure to PRS has a more adverse sex-dependent impact on behavioral outcomes than does earlier exposure to PRS, in a rodent model.

Hypoactivity and anxiety-like behavior

In adolescent offspring, the total distance traveled in an open field can be used as an indicator of locomotor activity or intrasession habituation (Bolivar, 2009), while the time spent in the central area can be used as an indicator of anxiety-like behavior (Prut and Belzung, 2003). Only male rats exposed to PRS during late pregnancy in our study showed decreased exploration and anxiety-like behavior in the open field. This is also broadly consistent with previous reports that prenatal stress during late pregnancy causes hypolocomotor activity and/or increased anxiety in the open field in both male and female offspring (Abe et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2013). However, in the present study, PRS exposure in late gestation did not disrupt locomotor activity in female offspring. In contrast, other studies have reported that female offspring who experience prenatal stress in late gestation were hypoactive and anxious (Bowman et al., 2004; Zagron and Weinstock, 2006), as evidenced by longer open field entry latencies or by less open arm frequency, central platform frequency, and less open arm duration in the elevated plus maze (Carola et al., 2002). Numerous researchers have reported that PRS in male rats results in prominent hypoactivity and anxiety-like behavior, while female rats are more prone to developing depression-like behavior (Zuena et al., 2008; Morley-Fletcher et al., 2011; Van Waes et al., 2011). Even though the behavioral results reported in other studies seem inconsistent with those from the current study, we note that none of the other studies had the same experimental design. In particular, the timing of stress exposure and the maternal stress paradigm differed, which might account for discrepancies. Further, discrepancies could have resulted from differences in the behavioral testing, such as the light/dark phase of the cycle in which the analyses were conducted, the age of evaluation, the sex and species of the animals used in the experiments, and the type of behavioral tests that were used to evaluate the same phenotype.

Offspring exposed to early PRS had no locomotor abnormalities in our study. To date, few studies have examined activity in animals exposed to stress in early/middle gestation. Our results are congruent with the reports of Mueller and colleagues who found that female mice exposed to stress (chronic mild variable stress) during early (middle) and late gestation had no disrupted locomotor behavior (Mueller and Bale, 2008).

Impaired recognition memory

On the NOR test, the lower DI observed in PRS-exposed animals could be due to a memory problem; they could not remember the familiar objects and thus treated both objects in the test phase as novel. We found that both sexes of offspring exposed to PRS (early or late) had recognition memory deficits. This is the first evaluation of the effect that restraint stress in early gestation has on recognition memory. Other researchers have studied different memory para-digms. For example, spatial learning and memory retrieval impairments were noted in male rodent offspring following early pregnancy stresses (GD 0-9) (Modir et al., 2014) and increased corticosterone levels in blood of pups of maternal deprivation rats has been reported (Uysal et al., 2011). Increased cortisol levels activate glucocorticoid receptors, which inhibits neuronal plasticity by reducing hippocampal long-term potentiation (Pavlides et al., 1993; Diamond et al., 2007). This, in turn, is thought to affect learning. We also found that exposure to prenatal stress during late pregnancy impaired recognition memory in both sexes. This finding supports the recognition deficits reported by Markham in male rat offspring (Markham et al., 2010) and by Ehrlich in female rat offspring (Ehrlich et al., 2015).

Depression-like behavior

In our study, both male and female offspring exposed to late PRS exhibited increased immobility on the FST, which is considered a depression-like phenotype in rodents (Guan et al., 2013; Darnaudery et al., 2004). Guan et al. (2013) and Darnaudery et al. (2004) used the same PRS model rats and found a similar depression-like pattern in both male and female rat offspring. Other studies using the same PRS model have suggested that males exposed to middle and/or late PRS have an increased vulnerability to depression (Zuena et al., 2008; Van den Hove et al., 2013). The different timings of the stress exposure might account for the differences between our FST data and that obtained by Zuena et al. (2008) (timing: GD 11 until delivery).

Additionally, we found that male offspring exposed to PRS during early pregnancy were immobile on the FST for more time than were the controls, suggesting that male offspring exposed to PRS during early pregnancy were also vulnerable to developing depression-related behavior. Mueller and Bale (2008) reported that male mice exposed to chronic mild variable stress during early gestation (GD 1-7) displayed depression-like behavior, while those exposed to middle (GD 8-14) or late (GD 15-21) gestation did not.

Higher levels of IL-18 in the ventral and dorsal hippocampus

In our study, ELISA and western blot analyses indicated elevated levels of IL-18 in the ventral and dorsal hippocampus of rats (male or female) exposed to PRS (early or late). Because early and late gestation are both critical periods for the development of hippocampal brain regions (Weinstock, 2001; Fatima et al., 2019), it is reasonable to conclude that PRS can impair hippocampal development. The ventral hippocampus (Henke, 1990; Fanselow and Dong, 2010; Marrocco et al., 2014) is specifically related to stress and emotions, whereas the dorsal hippocampus is involved in spatial learning, which may explain the results to some extent. Numerous studies indicate that IL-18 might modulate biological functions in the central nervous system during stress (Sugama and Conti, 2008; Alboni et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2017). IL-18 has also been reported to send signals via the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (i.e., extracellular signal-regulated kinase, ERK1/2, and p38) and Janus kinases/signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins (JAK/STATs) (Kalina et al., 2000). We and others have demonstrated that mitogen-activated protein kinase and the JAK/STAT pathways are disrupted when exposed to inflammation (i.e., lipopolysaccharide, PolyI:C, or IL-6) in vivo and in vitro (Heinrich et al., 2003; Deng et al., 2011; Minogue et al., 2012). Some researchers have also shown that cerebral damage leads to acute inf lammatory responses and neuronal damage through aberrant activation of the JAK/STAT3 pathway (Amani et al., 2019). A recent study showed that lipopolysaccharide could promote IL-18 secretion in the hippocampus, and might thus contribute to the depression-like behavior and memory deficit in mice exposed to LPS on day 0 (Zhu et al., 2017). Additionally, increased expression of IL-18 proteins in the frontal cortex and hippocampus caused by chronic glucocorticoid exposure participates in the amplif ication of the inf lammatory response and the promotion of apoptosis in those brain regions (Rothwell, 2003). Recent literature suggests that IL-18 reduces synaptic plasticity through impairment of long-term potentiation in the hippocampus (Curran and O’Connor, 2001). IL-18 may also contribute to caspase-1-dependent pyroptotic cell death, which has been demonstrated to be an important mechanism underlying depression (Vladimer et al., 2013). Higher levels of circulating IL-18 have been reported in patients with depression (Merendino et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2010) and IL-18 genetic polymorphisms influence depression relapses during treatment with antidepressants (Santos et al., 2016). Recent studies have found that IL-18 deficient mice show hippocampal abnormalities related to depressive-like or anxious behavior (Lisboa et al., 2018; Yamanishi et al., 2019). Although the above evidence suggests that IL-18 might be a potential biomarker of in-f lammation in patients with depression, no prior study has specif ically investigated the causal relationship between IL-18 and the phenotype of depression induced by PRS. This is the first study of IL-18 expression in the hippocampus in a PRS model. Future studies should explore the specific molecular mechanisms through which IL-18 mediates anxiety and depression phenotypes. This might provide a new theoretical basis for prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression and a new target for drug discovery and development.

Limitations

Because the data from the initial training session of the NOR test were not recorded or evaluated, we cannot rule out a group difference in exploration during the training step that may have contributed to the observed memory impairment.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that the behavioral abnormalities and biochemical alterations in the brains of PRS model rat off-spring are partially influenced by the timing of maternal exposure to stress. Late PRS exposure caused higher levels of anxiety-related behavior and depression in males, in addition to higher levels of depression-related behavior, impaired recognition memory, and diminished novel object exploration in both sexes. The effects of early PRS were more re-stricted. More importantly, this study further supports the idea that abnormal IL-18 levels contribute to the development of stress-related mental illness, such as anxiety and depression.

Acknowledgments:The authors would like to thank Grainne M. McAlonan from King’s College, London, UK; Liisa Laakso from the Griffith University, Gold Coast, Australia; and Michael J. Lukowicz from the University of Notre Dame, USA for their detailed modification of the manuscript.

Author contributions:Study conception and design: LJA, QLi; experiments performment: MXC, QLiu, SC, LL, LJA; data analysis: MXC, RW, TCKH, SC, LL, AJL; reagents/materials/analysis tools support: TCKH, PCS, LJA; manuscript writing: MXC, QLiu, SC, PCS, QLi, LJA. All authors approved the final manuscript version.

Conf licts of interest:There were no conf licts of interest in this experiment.

Financial support:This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81260296 (to LJA) and 81300987 (to QLi). The funding bodies played no role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Institutional review board statement:The experiments were approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee at Kunming Medical University, China (approval No. KMMU2019074) in January 2019.

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Data sharing statement:Datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

杂志排行

中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Recovery of an injured ascending reticular activating system with recovery from a minimally conscious state to normal consciousness in a stroke patient: a diffusion tensor tractography study

- Resveratrol corrects aberrant splicing of RYR1 pre-mRNA and Ca2+ signal in myotonic dystrophy type 1 myotubes

- EndoN treatment allows neuroblasts to leave the rostral migratory stream and migrate towards a lesion within the prefrontal cortex of rats

- Role of neurotrophic factors in enhancing linear axonal growth of ganglionic sensory neurons in vitro

- A double-network hydrogel for the dynamic compression of the lumbar nerve root

- The Akt/glycogen synthase kinase-3β pathway participates in the neuroprotective effect of interleukin-4 against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury