德国鲁尔区工业遗产的文化景观阐释——混合型工业文化景观

2020-02-25保罗拉维茨科孔洞一

(德)保罗·拉维茨科 孔洞一

1 世界文化遗产框架下的概念辨析

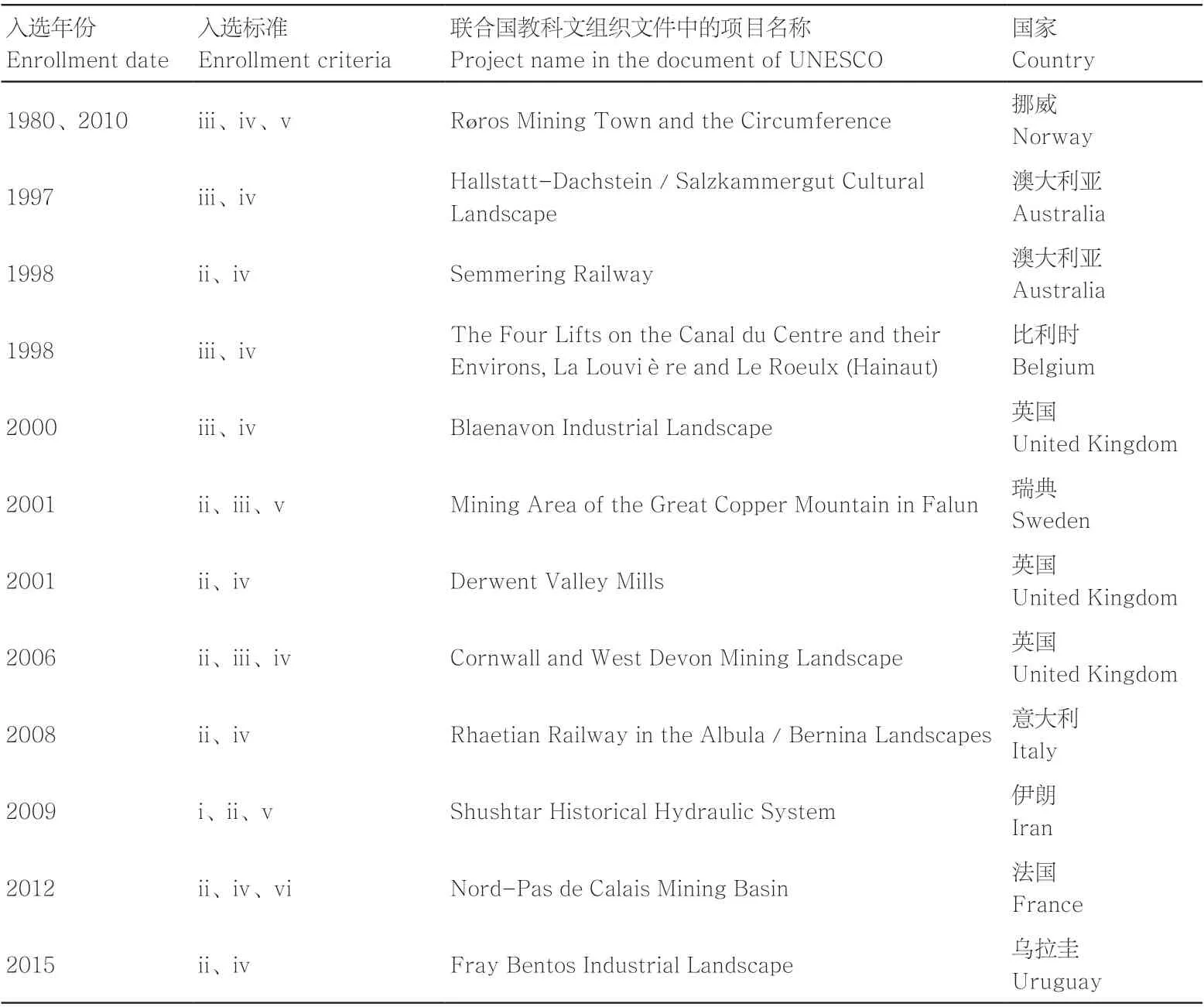

联合国教科文组织在1972年公布的《世界文化和自然遗产保护公约》(Convention Concerning the Protection of the Word Natural and Cultural Heritage,简称《世遗公约》)①中将文化遗产(cultural heritage)分为3类:古迹(monuments)、建筑群(group of buildings)、遗址(sites)[1]。《实施〈世界遗产公约〉操作指南》 (简称《操作指南》)中还强调了“文化景观、历史村镇或其他遗产中体现其显著特征的种种关系和动态功能也应予保存”[2]18。《操作指南》中将“文化景观”(cultural landscape)又具体分了 3个子类。i:人类刻意设计创造的景观(如园林和公园)。ii:有机演进的景观,其中a残遗(或化石)景观;b持续性景观。iii:关联性景观(非实体景观)[2]67。同时,《欧洲风景公约》(European Landscape Convention)②也延续了《世遗公约》对于“文化景观”的定义,强调文化景观是“人类改造自然的过程的产物这一特点”[3]。另外,国际古迹遗址理事会(International Council on Monuments and Cities, ICOMOS)③对其的定义主要突出具有普遍文化历史价值的“遗产景观”(monument landscape),也强调了文化景观是“在居住、经济和社会领域创造的文化成果对于人类居住环境空间的改造过程”[4]。同时,《历史性城镇景观》(Historic Urban Landscape)强调景观是“技术、场地、建筑和城镇区域”(technical, territorial, architectural and urban integrity)的综合体和“多学科协作”“公共参与”的评估与管理方法[5]。而《操作指南》中并未对于“工业遗产”(industrial heritage)和“工业景观”(industrial landscape)给出明确定义。我们对1980—2015年入选世界遗产名录的关于“工业景观”的相关项目进行了总结(表1)。

从表1可知,世界遗产中心对于“工业景观”的评定主要依据《操作指南》第77条列出的10项普遍性标准[2]6-17。其中ii:为在一段时期内人类价值观的交流;iii:为文明或传统文化提供见证;iv:是历史上建筑、技术或景观的杰出范例;v:是人与环境相互作用的杰出范例;vi:与具有突出普遍意义的文化与精神有联系。可见,这些评定标准也与一般的文化遗产一样,是“文化遗产”“文化景观”“遗产景观”“历史性城镇景观”等概念杂糅的结果,并不具有对工业景观的针对性。

由此可见,联合国教科文组织框架下,对“工业景观”相关概念的界定具有很大的模糊性。这样的模糊性会对实际的遗产评定和对工业文化景观相关的规划设计造成诸多困惑。因此,有必要对其进行研究。对“工业景观”的阐释,需要综合上述各个概念的内涵,并结合工业景观自身典型特点加以研究。笔者以德国鲁尔区为例,试图寻找一种针对工业景观的历史延展、内涵多样以及区域关联方面的阐释视角。

2 鲁尔区作为工业景观研究对象

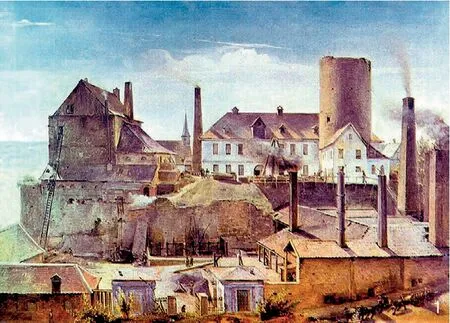

基于联合国教科文组织框架下的诸多遗产概念定义,德国鲁尔区是“工业景观”研究的绝佳案例。这主要体现在其工业文化景观的“历史性、区域性、综合性”特征上。地质勘探表明,从泥盆纪(Devonian Period)到第三纪(Tertiary Period)的亿万年岁月里,欧洲大陆的山脉、陆地和海洋分化完成,“现代生物”生存环境逐渐形成。鲁尔区也在该时期有着非常广袤的森林资源和动物生存痕迹,最终形成了现在莱茵河—鲁尔河—利普河之间的东西长120 km、南北宽70 km的广阔地质含煤层。在1—18世纪,鲁尔区从原始聚落发展为以农业经济为主的小型城镇和乡村地区。1758年,鲁尔区的Oberhausen地区就出现了第一个生铁工房。19世纪70年代,鲁尔区修建了将近300座矿井,成为当时欧洲大陆上最大的硬煤开采和焦炭生产区(图1)。1900年左右,鲁尔区又成为欧洲最大的钢铁生产基地。直到20世纪50年代,鲁尔区发展成为完备的工业化产业城镇集群,具有大规模的城市居住区和发达的工业水陆交通系统(图2),成为当时“欧洲煤钢共同体”(European Coal and Steel Community, ECSC)④中最大的综合性工业区[6]。“二战”后,鲁尔区经历了“去工业化”转型,传统的重工业在国家政策引导下逐步转化为以技术创新和文化创新为导向的新产业。在此过程中,工业时代的遗迹被广泛改造和再利用,例如:大型煤矿坑和沉陷区被改造为景观山(如Bottrop煤渣山);大型的煤钢生产工厂和设备也被改造为休闲娱乐设施(如杜伊斯堡北风景公园);工业废水和土壤经过改造成为自然生态系统的一部分(如Emscher河道改造);大部分工业时代的交通和基础设施依然维持着城镇的运转(如Oberhausen火车站);鲁尔区也有世界上面积最大、保持了20世纪初期“花园城市”风格的工业住宅区。从历史发展的脉络来看,鲁尔区的这些工业时代遗留的景观,不仅是19—20世纪中期欧洲大规模煤炭开采和钢铁生产的典范,而且也反映了这个区域在生产技术、生活方式、区域空间规划等方面的综合性发展。例如,德国鲁尔区的“埃森煤矿工业园”(Zollverein Coal Mine Industrial Complex in Essen)也在2001年依据《操作指南》第77条的ii、iii项标准[2]6-17,作为“煤炭的开采和处理以及焦炭生产所必需的建筑物和设备的完整综合体”列入了世遗名录中。而事实上,鲁尔区的工业景观与以上所列的12项“工业景观”项目一样,已经超越了“古迹、建筑群、遗址(场所)”的“文化遗产”概念,而作为“工业景观”综合 体系而存在。另外,鲁尔区的很多居住区和工业时代及前工业时代的小镇都符合《操作指南》中对“历史城镇”的评价细则中“尚有人居住的历史城镇”和“20世纪新城”的标准[7]。同时,许多矿井、厂房、交通设施、住宅区以及废料堆等不仅包涵了人类工业时代的“残遗景观”,并且已经在上百年的演化过程中与鲁尔区的城市、乡村和工业区融合成具备“有机演进”和“关联性”的文化景观区域整体[8]。由此可见,鲁尔区的文化景观具备了“历史性、区域性、综合性”的混合特 征,需要有新的研究视角和方法对其进行阐释和分析。

表1 世界遗产名录中的工业景观项目(1980—2015年)Tab. 1 Industrial landscape projects in the world heritage list (1980—2015)

1 19世纪初期的鲁尔区煤炭工厂Ruhr coal factory in the early 19th century

2 第二次世界大战之前的鲁尔区Oberhausen工业区Oberhausen industrial area in the Ruhr area before World War II

表2 混合型文化景观的视角和内涵Tab. 2 Connotations and perspectives of hybrid cultural landscape

3 视角与方法

3.1 “混合型工业文化景观”概念

“文化景观”概念在德国有着悠久的历史。从19世纪工业化时代就有自然地理学方面的关于人与自然关系的思考;在20世纪早期的自然保护与故乡保护思潮下发展出“区域性传统”;奥托 施吕特(Otto Schlüter)⑤的观点强调对“人类改造自然的历史片段”的关注;“二战”后,德国又出现了相对“自然 景观”而言,更强调人为干预过程的“文化景观”[9]。20世纪90年代,德国历史地理学派的“文化景观维护”(cultural landscape conservation,德语:Kulturlandschaftspflege)概念融合了以往概念中“生态、社会、美学”等多方面的内涵,从阐述角度强调文化景观是“人类生存过程中,随着一定的社会、经济、文化和审美需求变化而不断变化的环境空间”[10]。这一思想强调了景观自身的历史发展过程和基于人为适应而构建的多层次内涵特性。

2015年,“工业文化景观”这一名词首次在鲁尔区多特蒙德举办的ICOMOS国际“鲁尔工业文化景观”研讨会上被提出。作为对该项目研讨会的主旨性总结,由波恩大学Winfried Schenk教授提出了一个旨在阐述鲁尔区复杂的工业景观内涵的概念——“混合型文化景观”(hybrid cultural landscape)[11]。其对文化景观的阐释分为“本体性”(ontologische)和“构建性”(konstruktivistische)2个观察视角和4层含义 (表2)。

如表2所示,“本体性”视角包括了3层含义。第一层含义强调在景观生态学或自然地理学范畴下,景观作为地球物理空间和生态系统的一部分。第二层含义强调景观“人与环境关系”的内涵。其又包括4个含义:1)强调人与环境关系的物理层面的景观,即1992年《世遗公约》第1条中对文化景观的定义——人与环境的结合体(combined works of nature and man);2)强调心理层面的景观,即从客观物理空间获得的美学或心理感受;3)强调社会层面的景观,即文化景观可以理解为社会实践的物理表达和历史过程的产物;4)强调文化景观的地标符号象征意义。第3层含义是景观作为社会文化精神的隐喻表达。“构建性”视角强调景观作为沟通交流的结果。具体来讲,是在对文化景观“本体性”的科学阐释、评价的认知基础上,通过社会参与和公共讨论对其未来发展内涵所进行的诠释[12]。

3 鲁尔区工业文化景观要素分布Data collection of industrial cultural landscape elements in Ruhr area

对于鲁尔区“历史性、区域性、综合性”的工业景观而言,“混合型文化景观”概念可以为其提供一个全新的阐释视角。具体来讲,鲁尔区具有完整的区域范围的生态系统。虽然在工业时代自然系统遭到破坏,但是其生态系统的含义依然保持其关系完整性。同时,其人与环境互相作用的结果,在物理空间上体现为前工业时代和工业时代的文化景观要素与结构;在心理上体现为对工业文化的归属和自豪感;在社会文化上体现为适应于工业文明的社团与组织;并在区域的空间节点上形成地标性景观作为工业文明的象征。其文化隐喻更体现了工人阶级意志和市民精神。通过多层面的“本体性”内涵的诠释,为“构建性”文化景观的建立提供参照依据。在“构建性”内涵诠释过程中,需要借助于公共讨论。其中,“本体性”的重构与优化,往往需要与时代发展相结合。另外,利用“混合型工业文化景观”的视角,也可以解释鲁尔区融合城市、乡村和自然环境多个系统而形成工业化的“区间城镇”(Zwischenstadt)⑥在区域结构层面的内涵。因此,在此背景下,我们可以把这样的综合性概念称为“混合型工业文化景观”。

3.2 要素收集与分类

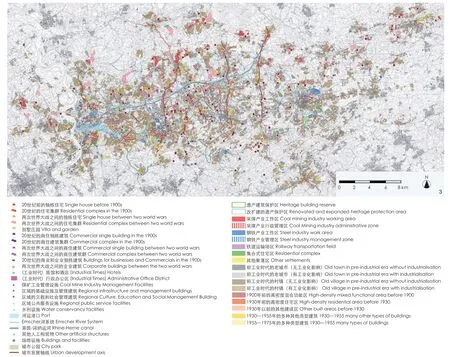

由于混合型工业文化景观具有多层面的复杂内涵,因此需要有科学客观的方法来收集和分析其对象要素,以“本体性”视角阐述文化景观要素和结构在“地质生态、人与环境关系、文化隐喻”多层面上的具体体现。借助于文化景观维护的2种基本方法——“清单盘点”和“空间区划”可以科学客观地对研究对象进行分析阐述。其中“清单盘点”是一种对研究对象进行整体性归纳的方法,收集、归纳、分析文化景观资源的类型、区域划分和历史演变过程;“空间区划”则是在一定的区域范围内,对历史性文化景观要素和结构进行收集、评估和分类,确定其“定义性特征”并登记在册、盘点清查[13]。在这样的清查和区划过程中,每个空间区域都应该基于“空间的特殊性”被识别、描述、评估和标注。鲁尔区文化景观要素与结构分布图(图3)将整个鲁尔区中“莱茵河—鲁尔河—利普河”所围合而成的区域作为对象来研究,有着广泛的时间和空间跨度:时间维度上,把19世纪以来的工业文化遗迹进行片段延续性划分;空间维度上,把住宅、商业、工业、基础设施和开放空间等多个层面的要素加以分析归纳。这样的数据收集和分析工作往往是庞大而繁杂的。基于地理信息系统的“文化景观数据库”——KulaDig⑦也为今天的研究者提供了非常方便的技术辅助。“工业文化景观要素”收集导则也在2007年的《北威州国土发展规划》(NRW Land Development Plan,LEP)中有所体现[14]。下面列举其部分分类和导则。

4 鲁尔区工业文化景观区域结构图Regional structure of industrial cultural landscape in Ruhr area

1)工业聚落文化景观:没有受到工业化影响的前工业时代(1900年前)的老村镇;工业时代(1900—1950年)的私人住宅(往往包含了特殊的工业特征);两次世界大战之间(1919—1935年)所修建的组团式社会住宅和廉租房;由公共建筑群所组成的工业城市中心区(如1929年建成的奥伯豪森中心);20世纪中期以前的资产阶级精英规划的别墅庄园和文化艺术区(如克努伯庄园)。

2)工业交通文化景观:作为工业化城市发展起点的“老火车站”,城乡融合型区域中的工业设施旁边的车站;工业铁路运输网络中的线路、设施及车站;人工河道系统和给排水系统;工业时代的水利运输系统。

3)工业设施与场地文化景观:为采矿业和钢铁业所建造的管理和运营场所;为采矿和钢铁业建立的厂房和基建设施;工业企业的历史性办公建筑和行会驻地建筑;废料地和采矿废弃地及其集合形态,如采矿堆、尖锥堆、梯台山等;采矿引起的沉陷区(自1900年以来,最高沉降达25 m)。

4)工业时代的开放空间:在住宅区和工业区之间分布的历史性道路和不连续的开放空间斑块;1950年以前建立的城市公园和绿地;自20世纪20年代以来建立的开放空间。

总之,采用文化景观的收集和评价方法可以对工业文化景观进行空间和结构系统上的划分。经过收集和评价的文化景观要素和结构体现了其“本体性”价值。如景观生态价值、地质科学价值、地方性文化价值、建筑遗产价值、传统农业经济价值、工业文化关联价值、阶级文化象征价值等。这样的工业文化景观结构系统表明:在过去工业时期,城市系统将一些功能从工业设施中分离了出来,从而形成功能用途改变了的“构建性”工业遗产,这些工业遗产也呈现出与当代的社会经济融合发展的趋势。

4 重构与发展

4.1 区域结构

在区域层面,文化景观的“本体性”价值受到区域内的人口与聚落发展、文化历史、社会经济以及政治制度变革等因素影响,呈现不同的空间结构特点。这些分散的空间结构需要在一定的发展目标下加以整合,为可持续发展提供依据。在2017年,德国鲁尔工业文化景观工作项目组向联合国世界文化遗产总部(UNESCO-Welterbe)递交了《鲁尔区工业文化景观》(Industrielle Kulturlandschaft Ruhrgebiet)报告。这份报告是基于文化景观数据收集和分析,集合了广泛的民众参与,对鲁尔区的工业景观进行了结构整合,并提出了构建性的“鲁尔区工业文化景观区域结构”(图4):1)以“莱茵河—鲁尔河—利普河”及“莱茵—诃纳运河”为主的河道景观; 2)工业时代铁路交通景观;3)历史性绿带;4)工业设施与场地景观;5)生态修复区。正如“构建性”含义所强调的,这是一种具有内在文化记忆和基因逻辑的、体现鲁尔区文化特色和未来可持续发展的混合空间系统结构。包括“基于工业景观改造的区域生态空间结构、以工业文化景观的逻辑为出发点破除传统城乡二分法的区域物理空间结构、保留工业文化遗产的历史记忆和内涵的社会文化构建,以及工业空间改造利用与当代经济发展适应的时代精神”[15]。在工业化转型的背景下,这样的结构系统也揭示了从“过去重工业的生产系统结构转变为当代的多种经济产业和空间结构交织”的新系统发展与变化的潜力。可见,“混合型工业文化景观”概念已经超出了单纯的工业景观保护范畴,具有整合区域空间结构的意义。

4.2 场地重构

“构建性”在空间上的具体体现就是场地重构。在这个过程中,需要重新发现原本工业废弃场地的“本体性”含义,并结合生态学、空间设计、文化心理等多方面的专业知识对本体性价值进行优化和强化。由煤钢工业废料构成的煤渣山(Halde)景观就是一种典型的场地重构(图5)。在前工业时代,这些矿产资源作为地质构造的一部分而一直存在;工业时代,人们赋予了矿产新的工业经济价值;随着工业时代的结束,经过开采后的废弃矿渣和旧机械失去了工业经济价值,但通过对其“本体性”含义的分析,可以从中得到丰富的景观内涵。在重构过程中,恢复自然生态属性往往需要漫长的过程。例如Tetraeder煤渣山景观就是20世纪90年代IBA Emscher Park项目的一部分,10年间对120 m高的煤矿废渣进行土壤改良和植物群落演替的生态改造,在其顶端设计建造了耗费210 t钢材的32 m高的大型三角锥地表景观构筑,体现了“征服自然”的工业文化精 神[16]。另外,哈尼尔(Haniel)仓库通过将煤矿排渣场设计成为市民可免费参与的现代化露天剧场,也体现了通过公共讨论反映市民精神的“构建性”过程,这样的诠释视角也适用于众多关于工业遗产的单体和群体建筑空间的改造和设计。例如,在关税联盟的主体建筑“鲁尔博物馆”内,人们体验到的不仅是 由矿井和厂房改造的空间,更能感受到鲁尔区整个文化景观的多层次历史内涵。依据地质、生态、历史、社会学等学科的研究,设计者在这个博物馆内展示鲁尔区自泥盆纪以来的地质与生境,也对人类社会从蛮荒到封建时代,以及近代的文化景观历史做了回顾,突出展示了19世纪以来的工业文化历程,并特别展示了20世纪80年代以来人们对文化景观的改造过程和结果。这也说明了文化景观的“社会、经济、文化和审美需求”[10]等方面的内涵是随着历史发展过程而变化的。这样的“变化过程”和“多层次内涵”已不能单独用“文化遗产”或者“工业景观”的概念来界定,而需要以混合型文化景观加以诠释。

4.3 文化意识重构

5 鲁尔区的煤渣山景观Halde landscape in Ruhr area

与《世遗公约》所提出的“关联性文化景观”内涵相一致,“构建性”内涵也包括人们对工业景观文化价值的继承与开拓。文化景观可以通过有形的空间和无形的文化活动,对参与其中的人起到文化意识引导和整合的作用。多年来,鲁尔区的工业景观保护与发展受到了政府和民间组织的支持,在“本体性”内涵的收集和整理阶段就有大量社会团体和民众参与,从而形成地方认同感和文化归属感。例如“鲁尔工业遗产之路”项目把本体性的“废弃物”重新诠释为“休闲设施”,如将废弃的铁路重构为串联起开放空间和工业遗迹的旅行线路(如自行车道)。著名的“煤气罐博物馆”中,采用了大型360°全息成像技术呈现了信息时代的“自然保护”主题,隐喻了旧工业时代“自然资源开发”的文化意识转变为当今时代的“自然保护”意识。同时,众多社会团体不仅通过日常休闲活动、博物馆和文教设施,还通过大型的国际性展览会对公众进行知识普及和美学教育,引导未来的文化意识创新。例如鲁尔区域联盟(Regionalverband Ruhr, RVR)、鲁尔景观协会(Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe, LWL)为鲁尔区申办2027年的国际园林博览会(International Gartenausstellung, IGA)提出了“整合性可持续性”的理念,包涵“生物多样性、交通可达性、能源节约性、休闲舒适性”的多目标,体现了对新时代工业文化意识的重构[17]。在这些“构建性”的公共讨论过程中,鲁尔区的文化景观意识也从单一的工业遗产价值认知,向多层含义的工业文化景观意识发展。

5 总结和展望

综上所述,《世遗公约》中对于“工业景观”的概念和评价标准呈现模糊性。鲁尔区的工业景观因其“历史性、区域性、综合性”等特点,已经很难用《世遗公约》中的单独概念来界定。从文化景观思想发展而来的“混合型工业文化景观”视角,可以将“文化遗产”“文化景观”等概念内涵加以整合,以“本体性”和“构建性”的观察视角,在“地质生态、人与环境关系、文化隐喻以及社会 交流”4个层面体现工业文化景观的特殊内涵。并且也使得工业景观突破了单纯遗产保护的概念,能够在产业转型的背景下,构建保留文化记忆和基因逻辑,体现工业文化特色和未来可持续发展的区域空间系统结构,诠释“生态、社会和文化”多层面的场地重构,并且为后工业时代的可持续文化意识的构建起到促进作用。

中国存在大量与鲁尔区规模和背景相似的工业文化景观区域。例如,东北的鞍山钢铁工业基地、山西晋北煤炭工业基地等都是规模巨大、内涵复杂且面临着工业转型的发展困境的综合工业区。工业遗产相关政策也提出对“遗产格局、结构、样式和风貌特征”进行认定和保护,以及“建设工业文化产业园区、特色小镇(街区)、创新创业基地”[18]的综合要求。在对这些工业文化区域进行研究时,需要认清世界遗产框架下的“工业景观”相关定义的局限,探索多维度的综合概念。而当前中国学界对于“工业景观”的研究大多是从设计学角度出发、对单体或集合的遗产要素进行的研究,将工业文化遗产作为“历史对象”[19],其焦点往往关注于场地内部自然要素和工业文化记忆[20]以及“文化碎片的复写”[21]。同 时,从中国工信部公布的3批国家工业遗产名单也可以看出,对工业景观的保护与发展尚停留在对“核心物项”[22]这样的单一工业遗产的保护层面。这样的视角都尚未跳出“遗产保护”视角的局限,不能作为综合性工业文化区域的研究工具。在这样的政策与理论背景下,“混合型工业文化景观”的阐释视角和科学分析方法可以为中国未来的工业景观研究提供开拓性的思路。最后必须强调,混合型工业文化景观的概念是在德国背景下产生的,其在中国的应用还需要从政策背景和社会条件方面因地制宜地进行探索。

注释:

①《世界文化和自然遗产保护公约》,是联合国教科文组织大会于1972年11月16日在巴黎举行的第17届会议上签署的针对世界范围内的文化和自然遗产的保护性框架协议。遗产分为:自然遗产、文化遗产和复合遗产3类,由ICOMOS等非政府组织协助参与世界遗产的甄选、管理与保护工作。

②《欧洲风景公约》,是依据欧盟委员会第176号决议,在2000年10月20日于佛罗伦萨召开的一次关于欧盟范围内的景观与国土保护与发展的框架协议。《欧洲风景公约》强调“文化景观”作为欧洲共同的历史文化载体,并声明文化景观保护是各个成员国的社会责任和义务,在此纲领下,各个成员国需要在城市、乡村和更广泛区域内进行关于自然与文化遗产保护的广泛合作。目前已经有41个成员国签署了这项协议。

③ 国际古迹遗址理事会,1965年在波兰华沙成立,是UNESCO的专业咨询机构。它由世界各国文化遗产专业人士组成,是古迹遗址保护和修复领域唯一的国际非政府组织,在审定世界各国提名的世界文化遗产申报名单方面起着重要作用。

④ 欧洲煤钢共同体,1951年4月18日通过《巴黎条约》成立,缔约国有法国、西德、意大利、比利时、荷兰及卢森 堡,是欧洲漫长历史上出现的第一个拥有超国家权限的机构,也是“欧洲共同体”和“欧盟”的前身。

⑤ 奥托 施吕特(1872 1959),德国地理学家,德国地理学会会员。先后任教于柏林大学、波恩大学、莱比锡大学,开创了利用自然地理学方法研究文化景观的先河。

⑥ 区间城镇,是德国当代著名规划学者Thomas Sieverts提出的一个规划理论。他把那些不具备城市或乡村明显界限的、趋于城乡融合的区域称之为“区间城镇”。这个理论对当代德国城镇规划有着重要的指导意义。

⑦ KulaDig是德国一个文化景观收集系统,基于地理信息系统,运用历史地理学分析方法,对点线面的文化景观要素进行收集和评价,并可以在地理信息系统中进行空间分析。目前KulaDig主要覆盖德国西部的几个州,广泛应用于国土规划、城镇规划、景观规划和文化遗产保护等领域。

图表来源:

图1来自德国画家Alfred Rethel于1834年创作的写生画; 图2由Regional Verund Ruhr提 供;图3由Hans-Werner Wehling提供,孔洞一翻译;图4~5由Stiftung für Industriedenkmalpflege und Geschichtskultur提 供,孔 洞一翻译;表1由孔洞一根据whc.unesco.org绘制;表2由Winfried Schenk绘制,孔洞一翻译。

(编辑/王亚莺)

Interpretation of the Cultural Landscape of the Industrial Heritage in the Ruhr Area of Germany: Hybrid Industrial Cultural Landscape

(DEU) Paul Lawitzke, KONG Dongyi

1 Analysis of Concepts Under the Framework of World Cultural Heritage

The “Convention Concerning the Protection of the Word Natural and Cultural Heritage” published by UNESCO in 1972 divides cultural heritage into three categories: monuments, group of buildings, and sites[1]. “The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention” (OG①) also emphasized that “the various relationships and dynamic functions that manifest their distinctive characteristics in cultural landscapes, historical villages or other living heritages should also be preserved[2]18. TheOGdivides “cultural landscape” into three subcategories specifically: i) Landscapes (such as gardens and parks) created by human deliberate design. ii) Organically evolved landscape: a remnant (or fossil) landscape; b continuous landscape. iii) Associative landscape (non-physical landscape)[2]67. At the same time, the “European Landscape Convention②” also continued to use the definition of “cultural landscape” in the “World Heritage Convention”, emphasizing that cultural landscape is “action and interaction of human and nature”[3]. In addition, the definition of the International Council on Monuments and Cities (ICOMOS③) mainly highlights the “monument landscape” with universal cultural and historical values, and also emphasizes that the cultural landscape is “inhabitation, economy and transformation process of the cultural achievements created by the social field to the space of human living environment”[4]. Moreover, the “Historic Urban Landscape (HUL)” also emphasizes that landscape is a combination of “technical, territorial, architectural and urban integrity” Evaluation and management method of “disciplinary collaboration” “public participation”[5]. However, there is no clear definition of “industrial heritage” or “industrial landscape” in theOGby UNESCO. We summarize the relevant items of the “Industrial Landscape” selected from the World Heritage List from 1980 to 2015 as follows ( Tab. 1).

It can be seen from Tab. 1 that the World Heritage Center's assessment of “industrial landscapes” is mainly based on the 10 universal criteria listed in Article 77 of theOG[2]6-17. The above table relates to some theme: ii) The exchange of human values over a period of time; iii) Providing witness to civilization or cultural traditions; iv) Outstanding examples of architecture, technology or landscape in history; v) The interaction between humans and the environment; vi) Connections with a culture and spirit of outstanding universal significance. These evaluation criteria are the same as the general cultural heritage. They are the results of the mixed concepts of “cultural heritage” “cultural landscape” “historic urban landscape”, etc.. It does not have the targeted (especially regional) industrial landscape.

Under the framework of UNESCO, the definition of the related concepts of “industrial landscape” is vague. This kind of ambiguity will cause a lot of confusion for the actual heritage assessment as well as the reconstruction of industrial heritage. Therefore, it is also necessary to study it. The interpretation of “industrial landscape” needs to integrate the connotations of the above mentioned concepts and study the typical characteristics of the industrial landscape. Starting from this theoretical phenomenon, this article takes the Ruhr area of Germany as a case study to try to find an explanatory perspective for the industrial landscape.

2 Ruhr Area as an Object of Industrial Landscape Research

Based on the definitions of heritage concepts under the UNESCO framework, the Ruhr area of Germany is an excellent case study of “industrial landscape”. This is mainly reflected in the “historical, regional and comprehensive” characteristics of its industrial cultural landscape in Ruhr area. Geological exploration shows that during the hundreds of millions of years from Devonian Period to Tertiary Period, the continental basis of the Ruhr area developed. The Ruhr area used to have very extensive forests and rich traces of animals and plants. It also formed a vast geological coal-bearing layer between the Rhine, Ruhr, and Lippe Rivers which is 120 km long from east to west and 70 km wide from north to south. In the 1-18th century, the Ruhr area developed from a primitive settlement to a small town and rural area dominated by the agricultural economy. In 1758, the first cast iron workshop appeared in the Oberhausen area of the Ruhr area. In the 1870s, nearly 300 mines were built in this region (Fig. 1). It became the largest hard coal mining and coke production areas on the European continent at that time. Around 1900, the Ruhr area became the largest steel production base in Europe as well. Until the 1950s, the Ruhr area has developed into a complete industrialized region (Fig. 2), accompanied by large-scale urban residential areas and a developed industrial transportation system, which is under the “European Coal and Steel Community④”, the largest comprehensive industrial zone[6].

After World War II, the Ruhr area experienced a “de-industrialization” transformation, and traditional heavy industry was gradually transformed into a new industry, guided by technological innovation and cultural innovation under national policies. In this process, the remains of the original industrial era were extensively transformed and reused: for example, large-scale coal mine pits and subsidence areas were transformed into landscaped hills (such as Tetraeder in Bottrop); large industry buildings and equipment were also transformed to leisure park (such as Duisburg North Park); industrial wastewater and soil have been transformed into a part of the natural ecosystem (such as the Emscher river channel reform); a large number of industrial-era transportation and infrastructure networks still maintain the operation of towns (such as Oberhausen Railway station); the Ruhr area also has the largest industrial residential area in the world, retaining the style of “garden city” in the early 20th century[7]. At the same time, many mines, factories, transportation facilities, residential areas and even waste piles of the industrial era are actually not only included of the “remnant landscape” of the human industrial era, but also have been a whole complex, which have merged in the process of evolution for hundreds of years with the rural and urban industrial areas into a whole of “organic evolution” and “relevance” of cultural landscape areas[8]. It can be seen that the cultural landscape of Ruhr area has a mixed feature of “historical, regional, and comprehensive”, which requires the new research perspective and method to explain and analyze it.

3 Perspectives and Methods

3.1 The Concept of “Hybrid Industrial Cultural Landscape”

The concept of “cultural landscape” has a long history in Germany. Since the industrialization era of the 19th century, there have been reflections on the relationship between man and nature in natural geography; the “regional tradition” was developed under the trend of natural protection and hometown protection in the early 20th century; Otto Schlüter's⑤point of view emphasized the “historical fragments of human transformation of nature”; after World War II, Germany has emerged the “cultural landscape” that emphasized human intervention processes relative to “natural landscapes”[9]. In the 1990s, the concept of “cultural landscape conservation” (“Kulturlandschaftspflege” in German) of the German historical geography school merged the connotations of the previous concept development, emphasizing the cultural landscape from the perspective of exposition, which are space and change in the transformation of certain social, economic, cultural and aesthetic purpose in the process of survival and living”[10].This idea emphasized the historical development of the landscape itself and the multi-connotations and-characteristics based on human adaptation.

The Conceptual noun “industrial landscape” was first mentioned at the ICOMOS “International conference of Ruhr Industrial Landscape”, which was held in Dortmund in February 2015. As a Keynote speech of the summary of project, Professor Winfried Schenk of the University of Bonn proposed a concept aimed at explaining the connotation of the complex industrial landscape in the Ruhr area: “hybrid cultural landscape”[11], which contained two perspectives in terms of “ontology” and “re-constructivity” and the meanings at four levels (Tab. 2).

As shown in Tab. 2, the “Essentialist-ontological” perspective includes different meanings. The first meaning is to emphasize the landscape as part of the geophysical space and ecosystem in the context of landscape ecology or natural geography. The second meaning emphasizes the connotation of landscape as “the relationship between man and environment”. This level is more divided into 4 Sub-meanings: 1) Landscape that emphasizes the physical level of the relationship between man and the environment. That is, the definition of cultural landscape in Article 1 of the 1992 World Heritage Convention — combined works of nature and man; 2) Landscape that emphasizes the psychological level of the landscape, that is the aesthetic or psychological feelings obtained from the objective physical space; 3) Landscape that emphasizes the social-level, it can be understood as the physical expression of social practice and the product of historical processes; 4) Landscape that emphasizes the symbolic meaning of the landmark. The third level of meaning is to use “landscape” as a metaphorical expression of social and cultural spirits. The “reflexive-constructivist” perspective is embodied at the fourth level: landscape as a result of communication. Specifically, it is an interpretation of its future development connotation through social participation and public discussion on the basis of the scientific interpretation and evaluation of the “ontology” of the cultural landscape[12].

For the “historical, regional and comprehensive” industrial landscape in the Ruhr area, such a “hybrid cultural landscape” concept can provide a holographic perspective for interpretation. Specifically, the Ruhr area has a complete regional ecosystem, which is composed of rivers, alluvial plains and some hills. It originated from hundreds of millions of years of geophysical processes, and it has completed characteristics during the pre-industrial era. Despite the destruction of the industrial age, today we still need to infer and analyze the meaning of this ecosystem. The landscape connotation as a result of the relationship between man and the environment is reflected in the physical space as a relic of the pre-industrial era and the industrial era; in the psychological and social meaning, it is reflected in the ownership and pride of industrial culture and associations and organizations; and the formation of landmark landscapes on the spatial nodes of the area as a symbol of industrial civilization. Its cultural metaphors further reflect the working class will and civic spirit. Through such multi-level interpretation of the “ontological” connotation, it provides a reference basis for the establishment of a “constructive” cultural landscape. In the process of “re-constructivity”, the public discussion that needs to be combined with the social development of the times, which has played a key role in the reconstruction and optimization of the “ontology” connotation. In addition, with the perspective of “hybrid industrial cultural landscape”, it can also explain the connotation of the regional structure of the Ruhr area, which combines multiple systems of urban, rural and natural environments to form an industrialized “interval town” (Zwischenstadt⑥). Therefore, in the context of the Ruhr area, we can call such a comprehensive concept “hybrid industrial cultural landscape”.

3.2 Elements Collection and Evaluation

The “hybrid industrial cultural landscape” requires a scientific and objective method to collect and analyze its core elements, due to its complex connotations at multiple levels. The “ontology” object is not only reflected in the spatial elements and structure, but also it has many connotations of “geological ecology, relationship between human and environment, cultural metaphor”. Through two basic methods “Inventories and regionalization”, the research objects can be analyzed and explained scientifically and objectively. Among them, “inventory “ is a holistic method to summarize and analyze the types, regional divisions and historical evolution of cultural landscape resources; “spatial division” refers to the historical cultural landscape elements and structure within a certain area to collect, evaluate and classify, determine its “definition characteristics” and register, inventory[13]. In the process of inventories and regionalization, each spatial elements and structures should be identified, described, evaluated, and annotated based on “spatial particularity”. The distribution “map of cultural landscape elements and structures in the Ruhr Area” (Fig. 3) takes the area enclosed by the rivers: Rhein, Ruhr, Lippe of the entire Ruhr Area as an object to study. It has a wide range of time and space: In the time dimension, the industrial-cultural relics from the 19th century are continuously divided into fragments; in the spatial dimension, the elements of multiple levels such as housing, commerce, industry, infrastructure and open space are analyzed and summarized. Such data collection and analytical work are often huge and complicated. With the help of the “cultural landscape database” based on geographic information system-KulaDig⑦, it also provides very convenient technical assistance for today's researchers. The collection guidelines for “Industrial Cultural Landscape Elements” were also reflected in theNRW Land Development Plan(LEP) in 2007[14]. Listed below are some of its classifications and guidelines.

1) Industrial settlement cultural landscape: old villages and towns in the pre-industrial era (before 1900) that were not affected by industrialization; private houses in the industrial era (before 1950) (often containing special industrial features); between the two world wars (1919—1935) built group social housing and low-rent housing; industrial city center composed of public buildings (such as the Oberhausen Center built in 1929); bourgeois elite before the mid-20th century Planned villa estate and cultural arts area (such as Villa Huge).

2) Industrial transportation cultural landscape: the “old railway station” as the starting point for the development of industrialized cities, the station next to the industrial facilities in the urban-rural integration zone; the lines, facilities and stations in the industrial railway transportation network; artificial river system and water supply and drainage system; Water system in the industrial age.

3) Industrial facilities and site cultural landscape: management and operation sites built for the mining industry and the steel industry; factory buildings and infrastructure facilities established for the mining and steel industry; historic office buildings and guild resident buildings of industrial enterprises; waste sites and mining Abandoned sites and their collection forms, such as mining piles, sharp cone piles, terraces, etc .; mining-induced subsidence areas (since 1900, the highest subsidence has reached 25 m).

4) Open space in the industrial era: historic roads and discontinuous open space patches distributed between residential areas and industrial areas; urban parks and green spaces established before 1950; open spaces established since the 1920s .

In short, the collection and evaluation methods of cultural landscapes can be used to give a spatial and structural division of industrial cultural landscapes. The elements and structure of the cultural landscape which are collected and evaluated reflect its “ontological” value. For example, landscape ecological value, geological scientific value, local cultural value, architectural heritage value, traditional agricultural economic value, industrial cultural connection, class cultural symbol, etc. Such an industrial cultural landscape structure system shows that during the period of deindustrialization, the urban system has separated some functions from industrial facilities, and formed a “re-constructive” industrial cultural heritage that changes the functional use, and presents contemporary social and economic functions.

4 Reconstruction and Development

4.1 Regional Reconstruction

At the regional level, the “ontological” value of the cultural landscape is influenced by factors such as population and settlement development, cultural history, social economy, and political system. That are always changing in the region, showing different spatial structure characteristics. These scattered spatial structures need to be integrated under certain development goals to provide a basis for sustainable development. In 2017, the German Ruhr Industrial Cultural Landscape Working Group submitted a report with the topic of “Industrielle Kulturlandschaft Ruhrgebiet” (in German) to the United Nations World Cultural Heritage (UNESCO-Welterbe). This report is based on the collection and analysis of cultural landscape data, gathering a wide range of public participation, structurally integrating the industrial landscape of the Ruhr area, and proposing a constructive “regional structure of the industrial cultural landscape of the Ruhr area” (Fig. 4): 1) River landscapes dominated by “Rhine-Ruhr-Lippe” and “Rhein-Herne-Kanal”; 2) Railway traffic landscape in the industrial era; 3) Historic green belt; 4) Industrial facilities and sites; 5) Ecological restoration area. As emphasized by the meaning of “re-constructivity”, this is a mixed spatial system structure with inherent cultural memory and genetic logic, reflecting the cultural characteristics of the Ruhr area and future sustainable development. Their features are: The regional ecological spatial structure based on the industrial landscape transformation; The regional physical spatial structure based on the logic of the industrial cultural landscape as a starting point to break the traditional urban-rural dichotomy; The social cultural construction is preserving the historical memory and connotation of the industrial cultural heritage; The preserve of the industry heritage adapted to contemporary economic development[15].” In the context of industrial transformation, such a structural system also reveals the potential for the development and change of a new system from the transformation of the production system structure of the past heavy industry to the interweaving of multiple economic industries and spatial structures in the contemporary era. It can be seen that the concept of “hybrid industrial cultural landscape” has exceeded the scope of pure industrial landscape protection and has the meaning of integrating regional spatial structure.

4.2 Reconstruction of Site and Building

The concrete expression of “re-constructivity” in space is the reconstruction of the site. In this process, it is necessary to rediscover the meaning of the ontological elements of the original industrial abandoned subject, and combine with the contemporary ecology, space design, cultural psychology and other professional knowledge to optimize and strengthen the ontological value. The coal debris hill (Halde) landscape is a typical site reconstruction(Fig. 5). In the pre-industrial era, these mineral resources have always existed as part of the geological structure; in the industrial era, people have given minerals new industrial economic value; with the end of the industrial era, the abandoned slag and old machinery after mining have lost the industrial economy value, but through analysis of the meaning of “ontology”, we can get rich landscape connotation. In the process of reconstruction, the restoration of natural ecological attributes often requires a long process. For example, the slagheap “Beckstr. with the Tetraeder” in Bottrop is part of the IBA Emscher Park project in the 1990s. In the past 10 years, the 120 m high coal mine residue was soil-improved and the ecological transformation of the succession of plant communities was designed. At the top of hill, 210 t of steel was / have been designed and built. The 32-meter-high large triangular cone surface landscape construction also reflects the industrial cultural spirit of “conquering nature”[16]. Another example of conservation is the Halde-Haniel which is designed as a modern open-air theater that citizens can participate in free of charge, and the result of public spirit was reflected through public discussions. Similarly, this interpretation perspective is also applicable to the transformation and design of numerous industrial heritage's single and group building spaces. For example, in the “Ruhr Museum”, the main building of UNESCO World Heritage Zollverein in Essen, people not only experience the spatial style transformed from mines and factories, but also experience the multilevel connotation of the history of the entire cultural landscape in the Ruhr area. Based on the study of geology, ecology, history, society and other disciplines, the designer displays the geology and habitat of the Ruhr area since the Devonian in this museum, as well as the history of human society from the wild to the feudal era and modern cultural landscape. In retrospect, it highlights the history of industrial culture since the 19th century, and especially shows the process and results of people's transformation of the cultural landscape since the 1980s. This also shows that the connotations of the “social, economic, cultural and aesthetic needs” of the cultural landscape[10]and other aspects change with the historical development process. Such “change process” and “multi-level connotation” can no longer be defined solely by the concepts of “cultural heritage” or “industrial landscape”, but need to be interpreted as a hybride cultural landscape.

4.3 Reconstruction of cultural awareness

Consistent with the connotation of “relevant cultural landscape” put forward by the “World Heritage Convention”, the “constructive” connotation also includes people's inheritance and development of the cultural value of the industrial landscape. The cultural landscape can play a role of guiding and integrating cultural awareness to the people involved through tangible spaces and intangible cultural activities. For many years, the protection and development of the industrial landscape in the Ruhr area have been supported by the government and non-governmental organizations. During the collection and sorting of the ontological connotation, there have been a large number of social groups and people participating, thus forming a sense of local identity and cultural belonging. For example, the “Ruhr Industrial Heritage Road” (Route der Industriekulur) project reinterprets the ontological “waste” as “leisure facilities”, such as the reconstruction of abandoned railways into travel routes (such as bicycle lanes) that connect open spaces and industrial heritage. In addition, the famous “gasometer”, the more than 100m high exhibition hall is presenting exhibitions, which use holographic imaging technology[17]. So the theme of “nature protection” in the information age, which also metaphorically transforms the cultural consciousness of “natural resource development” in the old industrial era into the “nature protection” consciousness of the present era.

5 Summary and Outlook

The concept and evaluation criteria of “industrial landscape” in the “World Heritage Convention” are vague. Because of its “historical, regional and comprehensive” characteristics, the industrial landscape in the Ruhr area has been difficult to be defined by a separate concept in the “World Heritage Convention.” The “hybrid industrial cultural landscape” perspective developed from the cultural landscape idea can integrate the conceptual connotations of “cultural heritage” and “cultural landscape”, with the “ontological” and “constructive” observation perspectives at the four levels of ecology, human and environmental relations, cultural metaphors and social communication, reflecting the special connotations of the industrial cultural landscape. It also makes the industrial landscape break through the concept of pure heritage protection. Under the background of industrial transformation, it can build a “regional spatial system structure that retains cultural memory and genetic logic, reflects industrial cultural characteristics and future sustainable development”, and interprets “ecological, social and cultural” multi-dimensional site reconstruction, and also promote the construction of sustainable cultural awareness in the post-industrial era.

There are a large number of industrial cultural landscape areas with similar scales and backgrounds to the Ruhr area in China. For example, the Anshan Iron and Steel Industry Base in Northeast China and the Jinbei Coal Industry Base in Shanxi Province are all large in scale, complex in content, and face development difficulties in industrial transformation. Industrial heritage-related policies also propose the identification and protection of “heritage pattern, structure, style and features”, as well as the comprehensive requirements of “building industrial cultural industrial parks, characteristic towns (blocks), and innovation and entrepreneurship industrial bases”[18]. To study these industrial cultural regions, it is necessary to recognize the limitations of the “industrial landscape” definition under the framework of the World Heritage and explore multi-dimensional comprehensive concepts. At present, most researches on “industrial landscape” in Chinese academic circles are based on the study of single or collective heritage elements from the perspective of design. The industrial cultural heritage is only regarded as “historical object”[19], and its focus is often on the interior of the sites and buildings with industrial memory[20]and “Replication of cultural fragments”[21]. At the same time, as can be seen from the three batches of national industrial heritage lists published by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of China, the protection and development of industrial landscapes still remain at the level of awareness of “core items”[22]. Such perspectives have not yet escaped the limitations of the “heritage protection” perspective, and should be developed to a research view for comprehensive industrial cultural areas. Under such a policy and theoretical background, the interpretation perspective and scientific analytical method of “hybrid industrial cultural landscape” can provide pioneering ideas for China's future industrial landscape research. Finally, it must be emphasized that the concept of a hybrid industrial cultural landscape was created in the German context, and its application in China also needs to be explored according to local conditions in terms of policy background and social conditions.

Notes:

① The Convention on the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage is a framework for the protection of cultural and natural heritage worldwide, signed at the 17th session of the UNESCO General Conference in Paris on November 16, 1972 protocol. Heritage is divided into three categories: natural heritage, cultural heritage and composite heritage. NGOs such as ICOMOS assist in the selection, management and protection of world heritage.

② The “European Landscape Convention” is a framework agreement on the protection and development of landscapes and territories within the EU on October 20, 2000 in Florence, based on the European Commission Resolution 176. The Convention emphasizes the "cultural landscape" as a common historical and cultural carrier in Europe, and declares that the protection of cultural landscapes is the social responsibility of each member country. Under this program, each member country needs to carry out natural and cultural heritage in cities, villages and a wide area Broad cooperation in protection. At present, 41 member countries have signed this agreement.③ The International Council of Monuments and Sites, established in Warsaw, Poland in 1965, is a professional advisory body of the World Heritage Committee (UNESCO). It is composed of professionals of cultural heritage from all over the world and is the only international nongovernmental organization in the field of protection and restoration of monuments. It plays an important role in examining and approving the list of world cultural heritage nominations nominated by countries around the world.

④ The European Coal and Steel Community was established on April 18, 1951 through the Paris Treaty. The parties are France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. It is the first European country to have supranational authority in the long history Institutions are also the predecessors of the "European Community" and "EU".

⑤ Otto Schrüter (1872 1959), German geographer, German geography and member. He has successively taught at the University of Berlin, the University of Bonn, and the University of Leipzig, and pioneered the use of natural geography to study cultural landscapes.

⑥ The interval town is a planning theory put forward by Thomas Sieverts, a famous German contemporary planning scholar. He calls those areas that do not have the obvious boundaries of cities or villages and tend to merge urban and rural areas to be called "inter-regional towns". This theory has important guiding significance for contemporary German town planning.

⑦ KulaDig is a cultural landscape collection system in Germany. Based on the geographic information system, historical geography analysis methods are used to collect and evaluate the cultural landscape elements of points, lines and areas, and spatial analysis can be performed in the geographic information system. At present, KulaDig mainly covers several states in western Germany and is widely used in land planning, town planning, landscape planning and cultural heritage protection.

Sources of Figures and Tables:

Fig. 1 © Alfred Rethel's sketch painting in 1834; Fig. 2 © Regional verund Ruhr; Fig. 3 © Hans-Werner Wehling, translated by KONG Dongyi; Fig. 4-5 © Stiftung für Industriedenkmalpflege und Geschichtskultur, translated by KONG Dongyi; Tab. 1 © KONG Dongyi, according to whc.unesco.org; Tab. 2 © Winfried Schenk, translated by KONG Dongyi.