Home Range Size and Overlap of the Small Nocturnal Schlegel's Japanese Gecko(Gekko japonicus),Introduced into a City Park in Korea

2019-12-27IlKookPARKDaeInKIMJonathanFONGandDaesikPARK

Il-Kook PARK,Dae-In KIM,Jonathan J.FONG and Daesik PARK

1 Department of Biology, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon, Kangwon 24341, South Korea

2 Science Unit, Lingnan University, Tuen Mun, New Territories, Hong Kong, China

3 Division of Science Education, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon, Kangwon 24341, South Korea

Abstract Studying the home range of an organism is important in understanding its ecology.Due to being cryptic,few studies have been conducted on the home range studies of small,nocturnal geckos.We conducted radio-tracking surveys for 23 individuals to estimate the home range size and home range overlap of the Schlegel's Japanese gecko(Gekko japonicus)previously introduced into a suburban city park.Individuals were commonly found in artificial structures(buildings and accessory structures)and on nearby natural trees.Daily moved distance was positively correlated with home range size.Minimum convex polygon(MCP)home range was 97.8 m2 for females and 99.5 m2 for males,on average.Gekko japonicus moved farther daily distances and used wider MCP and Kernel 95 home ranges in breeding season compared to non-breeding season,while the size of Kernel 50 home range did not differ between seasons.Both daily moved distance and home range size were not significantly different between sexes.In the breeding season,MCP and Kernel 50 home ranges of each gecko overlapped with 32.4% and 13.8% of remaining geckos,respectively.Our results not only show that 1)G.japonicus uses both artificial structures and adjacent natural trees as microhabitat,but also suggest that 2)G.japonicus is non-territorial,but has a core habitat that is shared with few other individuals,and 3)the reproductive system of G.japonicus is polygamous.

Keywords radio telemetry,invasive species,territory,lizard,Korea

1.Introduction

Home range is defined as the area regularly used by an animal for foraging,avoiding predators,and reproduction(Burt,1943).Home range provides information on habitat range,available resources,and dispersal potential to nearby areas(Locey and Stone,2006;Perry and Garland,2002;Rose,1982).In addition,comparison of home range size and overlap among individuals provides information on resource competition,interaction between sexes,and breeding system(Ferner,1974;Kerr and Bull,2006;Stamps,1977).Thus,determining home range is important in understanding the ecology of a species.

In lizards,studies on home range have focused on invasive,endangered,or relatively large species(Gerner,2008;Gomez Zlatar,2003;Kimet al.,2012).This is largely due to logistic difficulties in studying small,cryptic,nocturnal species(Kalwinski,1991;McIvor,1972;Rose and Barbour,1968).Traditionally,the markrecapture method has been used to study lizard home range(Klawinski,1991;McIvor,1972;Stamps,1977).However,radio telemetry has recently been used,which can give more precise information on home range and movement patterns(Gerner,2008;Kerr and Bull,2006;Kimet al.,2012;Stellatelliet al.,2016).Due to the difficulty in observing of nocturnal geckos living in forests,few of such studies have been conducted.Particularly,home range determination by radio telemetry has not been conducted on any nocturnal geckos.

Schlegel's Japanese gecko(Gekko japonicus)is a small,nocturnal gecko,distributed in China,most main islands of Japan,and southern parts of the Korean Peninsula(Leeet al.,2004;Wada,2003;Zhao and Adler,1993).Populations ofG.japonicusin Japan and Korea are considered introduced(Leeet al.,2004;Toda and Yoshida,2005).This species mainly inhabits urban residential areas and city parks in Korea and Japan,but is also found in forests in China(Leeet al.,2004;Ota and Tanaka,1996;Zhanget al.,2016).Gekko japonicusconsumes insects and other arthropods that are attracted to city lights in urban environments(Ota and Tanaka,1996;Werneret al.,1997).Despite various behavioral,ecological,and genetic studies onG.japonicus(Kimet al.,2018,2019;Parket al.,2018;Tawaet al.,2014;Todaet al.,2003;Zhanget al.,2009),we do not have any data on home range of this species.Considering thatG.japonicusoccupies an important ecological niche in urban ecosystems(Brooke Stableret al.,2012;Leeet al.,2004)and additional dispersal/introduction ofG.japonicusis expected in Korea and Japan,it is necessary to determine its home range.

In this study,we used radio telemetry to understand the home range ofG.japonicusin a suburban city park.We had three specific questions to investigate:1)ifG.japonicusare found on both artificial structures and natural trees in nearby forest,2)if home range varies between season and sex,and 3)if the home range of individuals overlap.

2.Materials and Methods

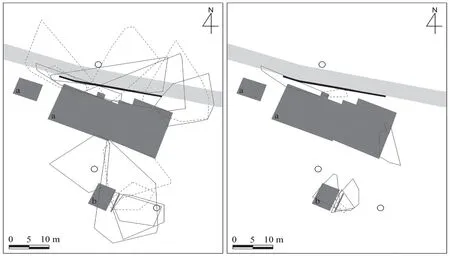

2.1.Study site and gecko collectionAs a study site,we selected parts of a suburban city park in Busan,Korea(N 35°13',E 129°04',70 m×70 m),where we could freely approach the various habitats at night.A schematic of the site is in Figure 1.The site contained a two-story cablecar building(31 m long×13 m wide×12 m high),a toilet building(8 m long×6 m wide×4 m high),and adjacent pine forest surrounding these buildings.The first floor of the cable-car building has a small convenience store and a daycare center.On the northeast side of the cable-car building,there were three wooden paths(2.8-5.2 m wide×1.5-2.8 m long)and a artificial rock wall(0.5 m wide×35 m long)between the building and park walkway.In the forest,the upper layer was comprised ofPinus densifloraandChamaecyparis pisifera,while the lower layer was comprised ofRhododendron schlippenbachii,Camelliajaponica,andCornus controversa.Some pine tree branches touched or extended over the cable-car and toilet buildings.There were three street lights:one at north-east side of cable-car building and two at near toilet building,approximately 3.2-14 m away from the buildings.These street lights automatically turned on at 1800 and off at 2330.Lights in the convenience store irregularly turned on and off.In addition,the site was illuminated by dim city lights at night.

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of the study site and the minimum convex polygon(MCP)home range of female(solid line)and male(dotted line)Gekko japonicus,which radio-tracked in a suburban city park during(A)breeding(June 8-July 10)and(B)non-breeding(October 2-24,2018)season.a,cable-car building;b,toilet building;O,street lights.Black and light gray bars at the north-east side of the cable-car building indicate artificial rock wall and park walkway,respectively.Three wooden paths exist between the rock wall and the cable-car building and the pine forest surrounds the buildings(not shown for clarity).

We captured geckos on the walls of cable-car and toilet buildings by hand or using insect nets.Considering the weight of the radio transmitter,we only collected adult geckos whose body weight was over 4 g.After recording the exact capture location on the mimetic diagram of the study site(Figure 1),geckos were individually marked with a small paint dot(Paint marker,Munwha,Seoul),kept in a collecting box(19 cm long×12 cm wide×13 cm high),and transported to the field station approximately 650 m from the study site.

2.2.Attaching transmitters and conducting radiotrackingThe radio transmitters we used were PicoPip(173 MHz,size 12 mm long×7 mm wide×4 mm high,battery life 21 days,weight 0.35 g;Biotrack,Wareham,UK).We constructed a transmitter package by first attaching the transmitter to prepared‘X' shaped sport tape(5 mm wide,Nasara,Paju,South Korea)using power epoxy steel(Locstar,Warwickshire,UK)following previous studies(Kimet al.,2012;Winkel and Ji,2014).The weight of the prepared package was 0.42±0.01 g(n=23).After measuring snout-vent length(SVL)and body weight(BW)of each individual using electronic calipers(nearest 0.1 mm;CD-15CPX,Mitutoyo-Korea,Seoul)and a digital balance(nearest 0.01 g;MH-200,Sellbuy,China),we attached the transmitter package to the individual by applying small amount of super glue(Loctite-401,Henkel,Germany).The ratio of transmitter to body weight of individuals was 8.3%±0.3%(5.2-10.0,n=23).Individuals wearing the transmitter package were kept in a box(19 cm long×12 cm wide×13 cm high)for more than one hour to confirm that the package was stable and did not disturb activity.All geckos were released at the collection site within 12 hours of its initial capture.

We conducted radio-tracking during both the breeding(June 8 to July 10,2018;33 days)and non-breeding season(October 2 to 24,2018;23 days)using an IC-R20 receiver(Icom,Osaka,Japan)connected to a 3-element Yagi antenna(173 MHz,Biotrack,Wareham,UK).In this study,we defined the breeding and non-breeding season based on if females have visible eggs in their abdomen,considering previous results on the reproductive biology of this species(Ikeuchi,2004;Jiet al.,1991).In the nonbreeding season,all females did not have visible eggs,but in the breeding season,6 out of 7 females had visible eggs.To increase the number of detections while not excessively disturbing geckos,we determined the location of individuals twice each day,once between 09:30-14:00 and once between 21:00-02:00.When we were unable to directly observe individuals(e.g.,inside structures or high on trees),we determined location using a trigonometry(Kimet al.,2012;Raet al.,2008).

We determined geckos' location and classified as either artificial structures(i.e.,building,wooden path,artificial rock wall,and electric pole)or natural structures(i.e.,tree,natural rock,and forest floor).In this study,when presenting the pooled artificial and natural structures as different microhabitats,we used words of“building microhabitat' and“tree microhabitat”for each structure group.The location was recorded on a map,and we noted two reference distances from the building at 0.1 cm unit.We measured these two distances using a laser distance meter(Fluke-414D,Fluke,Everett,USA).We did not record locations using GPS coordinates due to their inaccuracy at such a small spatial scale.We measured the moved distance of an individual by measuring the shortest distance between the current and previous location using the laser distance meter.

When a gecko was directly observed,we recorded the locating time as the time after sunset and measured body surface temperature to the nearest 0.1°C within 2 m from the gecko using an infrared digital thermometer(D/S Ratio:12:1,Fluke-AR330,Fluke,Everett,USA).To record daily temperature(0.1°C)and humidity(0.1%)every 30 min during the study period,we placed three EasyLog data loggers(Lascar,Whiteparish,UK)on the outer wall of the cable-car building approximately 2 m high from the ground.

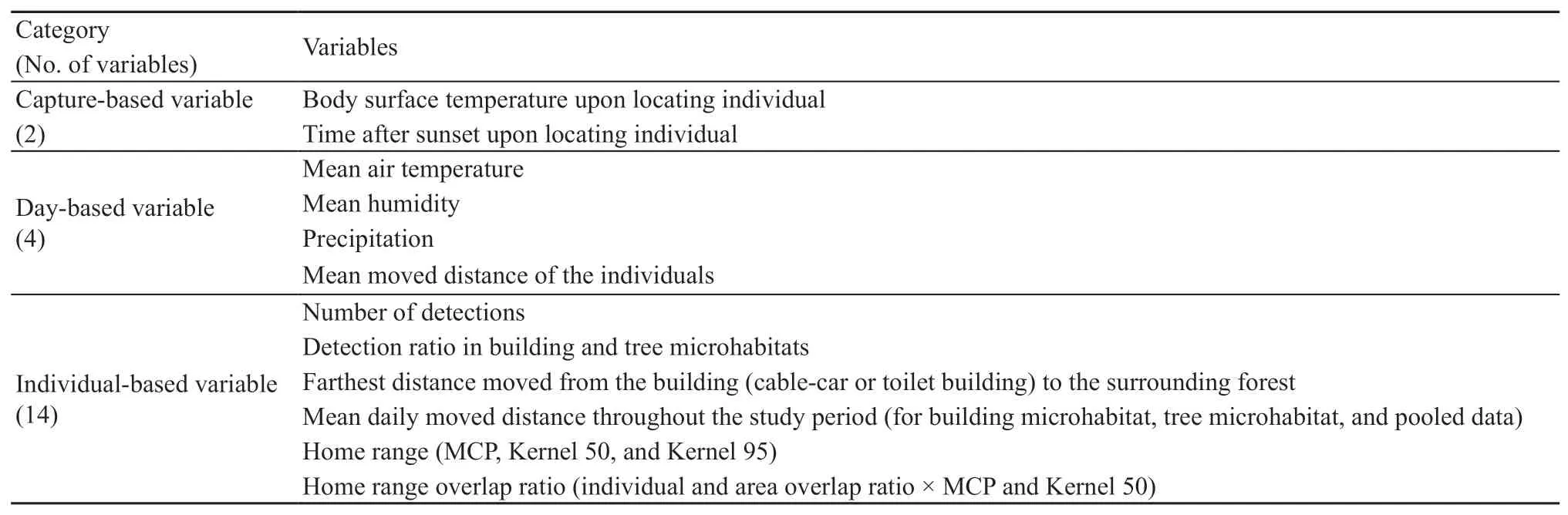

2.3.Handling dataVariables analyzed in this study consisted of 2 capture-,4 day-,and 14 individual-based variables(Table S1).We generally compared these variables between seasons and sexes.Capture-based data were the body surface temperature of an individual when located and the locating time of each gecko.Day-based data consisted of mean air temperature and humidity,precipitation,and mean moved distance.The temperature and humidity were daily means from the three EasyLog data loggers.Daily precipitation data were obtained from Busan meteorological station(https://data.kma.go.kr),which was 13 km away from the study site.Mean daily moved distance was calculated as the mean value of collected daily distances of all individuals for a particular date.

Individual-based data consisted of the number of detections,detection ratio in building microhabitat or tree microhabitat,farthest moved distance from the building to the forest,mean daily moved distance,home range size,and home range overlap ratio.The detection ratio in building(or tree)microhabitat was calculated as the number of detections in building(or tree)microhabitat divided by total number of detections.The farthest moved distance from the building was the distance between the furthest location into forest and the edge of the building.The mean daily moved distance was the mean of all collected daily moved distances of an individual during the radio-tracking period.A daily moved distance was only obtained when a gecko was detected over three consecutive times(i.e.,day-night-day)so that the distance included both one day-time and one nighttime moved distance.The mean daily moved distance was also calculated separately for each building and tree microhabitat.

For home range,we calculated minimum convex polygon(MCP),Kernel 50,and Kernel 95 home range using a batch home range processing tool in QGIS v3.4(https://www.qgis.org/en/site/).We selected the three different home range estimators in order to compare with previous results on the home range size and overlap of other lizards and geckos.MCP and Kernel 95 represent meaningful maximum home range,while Kernel 50 represents core home range(Börgeret al.,2006;Robles and Halloy,2010).Individual and area overlap ratios were calculated using MCP and Kernel 50 home ranges(Diego-Rasilla and Pérez-Mellado,2003;Kerr and Bull,2006;Robles and Halloy,2010).The individual overlap ratio was calculated as the number of individuals of which home range overlapped with the target individual,divided by the number of all remaining individuals being radio-tracked during the period.The area overlap ratio was calculated following the Cooper(1978)'s method.In detail,we first calculated the overlap area ratio of each individual whose home range overlapped with a target individual by dividing the overlapping area between the two individuals by the smaller home range of the two individuals.Then,we calculated the mean value of the obtained area overlap ratio of the all geckos,of which home range overlapped with the target individual.

2.4.Statistical analysesAll analyses were done in SPSS v.24.0(SPSS Inc.,Chicago,USA).Numeric data were presented as mean±1 standard error if not specifically mentioned.

Seven out of 23 variables(including SVL and BW)were not normally distributed(Kolmogorov-Smirnov,Ps<0.05).First,we used a Spearman correlation test to know relationships among day-based data of mean daily air temperature and humidity,precipitation,and pooled daily moved distance.If the certain pooled data showed significance,we subsequently analyzed the relationship separately for breeding and non-breeding season.We used the same test to analyze relationships among individualbased data of the number of detections,SVL,BW,detection ratio in building microhabitat,farthest distance from the building,daily moved distance(for building microhabitat,tree microhabitat,and pooled data),home range size(MCP,Kernel 50,and Kernel 95),and home range individual and area overlap ratio(MCP and Kernel 50).

To know if the body surface temperature of geckos differed between seasons and sexes,we analyzed the data using a univariate general linear model(UGLM).In the analysis,the locating time was used as a covariate.For individual-based data,we used a multivariate general linear model to test for differences based on seasons and sexes in detection ratio in building microhabitat,mean daily moved distance(for building microhabitat,tree microhabitat,and pooled data),farthest distance from the building,and home range size(MCP,Kernel 50,and Kernel 95).In this analysis,the number of detections,SVL,and BW were used as covariates.We also used the UGLM to test for difference in home range overlap individual and area ratio between seasons and between sexes.In addition,difference in daily moved distance between building and tree microhabitats with regard to seasons and sexes was tested by the pairedt-tests.Finally,we used an independent sample t-test to test if mean daily air temperature,humidity,and precipitation were different between seasons.

3.Results

3.1.General trendsWe radio-tracked 15 geckos(7 females and 8 males)in breeding season and 8(2 females and 6 males)in non-breeding season(Table S2).The mean number of detections was 38.4(±11.8 SD,n=23).We directly observed geckos in 254 out of 882 total detections(31.5%±25.6% SD,n=23).The number of detections did not differ both between seasons and between sexes(Ps>0.05).The size of females(SVL,66.2±1.4;BW,5.9±0.2,n=9)was larger than males(SVL,62.0±0.4;BW,4.7±0.1,n=14;P=0.003 for SVL andP<0.001 for BW),but the SVL and BW did not differ between seasons(Ps>0.05).

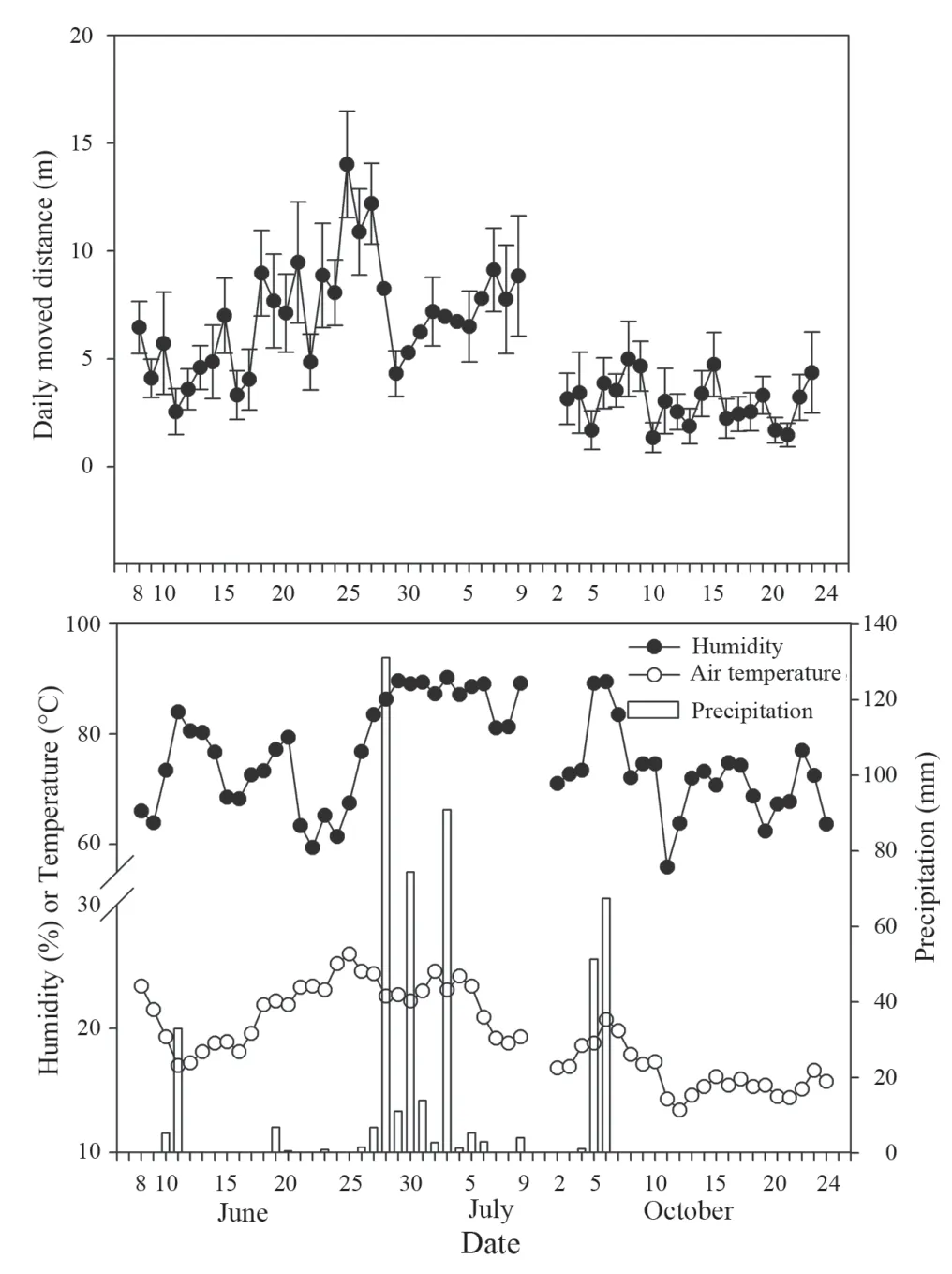

Figure 2 Mean daily moved distance(A)of Gekko japonicus along local climate(air temperature,humidity,and precipitation,B)conditions during breeding season(June 8-July 10,2018),and nonbreeding season(October 2-24,2018).

Mean daily air temperature was higher in the breeding season(21.5±0.5,n=27 days)compared to the nonbreeding season(6.3±0.4,n=23 days;t=7.9,df=48,P<0.001),but mean humidity and precipitation did not differ(Ps>0.05).Overall mean daily moved distance was positively correlated with only mean daily air temperature(r=0.788,n=47,P<0.01,Figure 2).In separate analyses,the relationship was seen in breeding season(r=0.593,n=26,P<0.01),but not in non-breeding season(P>0.05).Body surface temperature of geckos was higher in the breeding season(corrected mean±SE,24.0±0.3,n=141)compared to non-breeding season(18.0±0.5,n=113;F1,254=75.82,P<0.01),but the body surface temperature did not differ between females(21.0±0.5,n=114)and males(21.3±0.3,n=140;P>0.05)

3.2.Daily moved distanceIn individual-based analyses,mean daily moved distance in building microhabitat was positively related with the number of detections(r=0.439,n=22,P=0.041).The remaining relationships were not significant(Ps>0.05).

We detected geckos in both building microhabitat(54.9%±5.9%,n=23)and tree microhabitat(45.1%±5.9%,n=23,Table 1).In building microhabitat,we detected 74.8%(357 out of 477 detections)of geckos on walls or inside building structure,17.0%(81 detections)on/in the wooden path structure,and 4.8%(23 detections)on/in the rock wall structure,and 3.4%(16 detections)in other structures(e.g.,on electric poles).In tree microhabitat,98.5%(399 out of 405 cases)of detections were on branches and bark of tree trunks,and only six times were on the forest floor structure.The detection ratio in building and tree microhabitat was not different between seasons,between day-time and night-time,andbetween sexes(Ps>0.05).However,detailed use of different structure types was different between sexes and between seasons,but not between day-and night-time(Table S3).

Table 1 Detection ratio in building microhabitat,daily moved distance,farthest distance moved toward the forest,and home range size ofGekko japonicus.

Mean pooled daily moved distance was not different between seasons(P>0.05),but the daily moved distance in building microhabitat(F1,20=5.02,P=0.045)and tree microhabitat(F1,20=12.93,P=0.004)were different between seasons(Table 1).Any of the daily moved individual distances were not different between sexes(Ps>0.05).Daily movement was farther in tree microhabitat than in building microhabitat(pairedt=5.19,df=19,P<0.01,Table 1).This trend was seen in breeding season(t=5.19,df=19,P<0.01),but not in non-breeding season(P>0.05).Further daily movement in tree microhabitat was also indicated when the data for males and females were analyzed separately(female,t=2.93,df=7,P=0.022;male,t=4.15,df=11,P=0.002).

Individuals moved farther distance from the building toward the forest during breeding season(13.8±1.4 m,n=15)compared to non-breeding season(4.7±1.1 m,n=8),but the distance was not significant different between sexes(P>0.05,Table 1).

3.3.Size and overlap of home rangeMCP home range was positively correlated with the number of detections(r=0.488,n=23,P=0.018),while the SVL of geckos was negatively correlated with Kernel 50 home range(r=-0.485,n=23,P=0.019).The remaining relationships were not significant different(Ps>0.05).In addition,the individual-and area-based overlap ratios of home range were not related with any tested variables(Ps>0.05).

MCP(139.9±21.2 m2for breeding and 21.8±5.3 m2for non-breeding season;F1,23=8.98,P=0.009)and Kernel 95(170.2±31.1 m2for breeding and 31.3±8.6 m2for non-breeding season;F1,23=5.43,P=0.033,Table 1)home ranges were greater in the breeding season compared to non-breeding season,but Kernel 50 home range was not different between the seasons(27.0±6.9 m2for breeding and 5.7±1.7 m2for non-breeding season;P>0.05,Table 1).The size of any of home range types was not different between sexes(Ps>0.772).

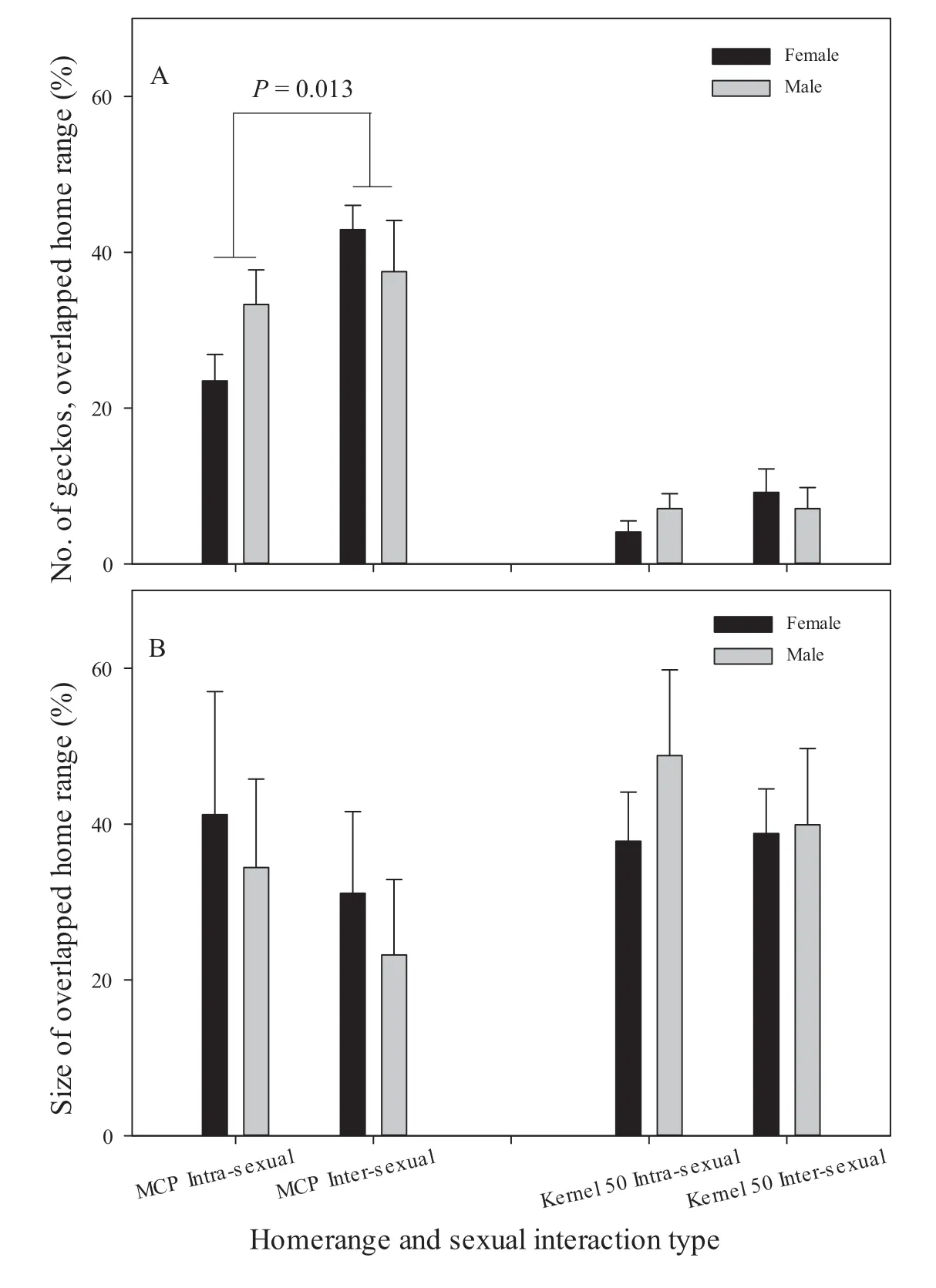

The overlap ratio of MCP and Kernel 50 home range individual(MCP,F1,23=10.0,P=0.005;Kernel 50,F1,23=7.3,P=0.014)and area(MCP,F1,23=7.4,P=0.014;Kernel 50,F1,23=17.9,P<0.01)was greater in the breeding season than non-breeding season(Table 2).MCP individual(F1,23=7.0,P=0.016)and area(F1,23=4.6,P=0.046)overlap ratios of males were bigger than those of females,but the ratios of Kernel 50 were not different between sexes(Ps>0.500,Table 2).In addition,we provide the results of individual and area overlap ratio of MCP and Kernel 50 home ranges between intra-sexual and inter-sexual individuals as supplementary materials(Table S2,Figure S1),considering relatively small sample cases of intra-sexual and inter-sexual overlaps,particularly in non-breeding season.

4.Discussion

To estimate the home range size and overlap ofG.japonicus,we radio-tracked individuals during both breeding and non-breeding season.Gekko japonicusused both artificial structures and adjacent natural trees as microhabitat and its MCP home range was 97.8 m2for females and 99.5 m2for males,on average.Consideringindividual and area overlap ratio of MCP and Kernel 50 home range among geckos,G.japonicusis likely non-territorial and its reproductive system is likely polygamous.

Table 2 Individual and area overlap ratio of the MCP and Kernel 50 home range of Gekko japonicus.No.,number;Ind.,individual;intra,intra-sexual;inter,inter-sexual.

Regardless of season and sex,G.japonicusused both building and tree microhabitats.In the artificial or urban habitats,introduced animals including nocturnal geckos often find refuge in various crevices in manmade structures and efficiently feed on abundant insects(Francis and Chadwick,2012;Saenz,1996;Williams and McBrayer,2007).In particular,when geckos are introduced into cooler areas compared to their original habitat,building or house habitat can provide a suitable hibernaculum with stable temperature(Brooke Stableret al.,2012;Locey and Stone,2006;Norden and Norden,1991).In the study site,G.japonicusused both artificial structures and adjacent natural trees as microhabitat although they often moved farther in tree microhabitat.Despite some potential bias in our observations because we initially captured all geckos from the buildings,our results have two important implications in the understanding the habitat use of nocturnal geckos.First,ecological field data of nocturnal geckos may be biased,as observations in previous studies are often from individuals,which gathered at light sources on various walls(Eifleret al.,2017;Gomez-Zlatar,2003;Parket al.,2018).To get a complete view of nocturnal gecko ecology,adjacent natural microhabitat such as trees and plants needs to also be considered.Second,our study reveals that nocturnal geckos living in residential areas or city parks would also use plants and trees as the components of its microhabitat.When managing an area for gecko conservation,these vegetation need to be included into the management plan.

The home range size of a species generally depends on habitat structure,distribution of prey and refuges,and body size and reproductive system of the species(Perry and Garland,2002;Stellatelliet al.,2016).MCP home range of the Pacific gecko(Hoplodactylus pacifcus;McIvor,1972)and Mediterranean gecko(Hemidactylus turcicus;Klawinski,1991;Rose and Barbour,1968),which are small nocturnal species,was approximately 2.2 m2and 4.1 m2,respectively.In this study,G.japonicushad much bigger MCP home range as about 99 m2for both females and males.Two factors might be responsible for this result.First,compared to traditional capturerecapture methods,using the radio-tracking method allow for easier detection of cryptic species,likely resulting in a much larger home range.Second,during the study period,H.pacifcusandH.turcicusused single microhabitat types,such as buildings or small mountain hill(Klawinski,1991;McIvor,1972).Unlike them,G.japonicusused two different microhabitat types of both building and trees in this study,resulting in a bigger home range.

In the breeding season,G.japonicusused a larger MCP and Kernel 95 home range than in non-breeding season.To meet increased energy requirements during the breeding season,a large home range is necessary(Perry and Garland,2002).The result thatG.japonicusincreased its daily moved distance and travelled farther distance to the forest in breeding season could be responsible for a home range expansion during the breeding season.As we found a positive correlation between daily moved distance and mean air temperature in this study,increased air temperature in breeding season could also facilitate increased moved distance and home range through higher body temperature(Hu and Du,2007;Hueyet al.,1989).On the other hand,the size of Kernel 50 home range was not different between seasons.This result might be a result of female and maleG.japonicushaving a core habitat,regardless of season.We discuss this in further detail below.

All home range coefficients evaluated in this study did not differ between sexes.In general,home range of females is determined based on the distribution of essential resources,while that of males based on the female distribution and additional resources(Perry and Garland,2002).So,males generally have larger home range than females(Ikeuchiet al.,2005;McIvor,1972;Stellatelliet al.,2016).Indifferent home range size between female and maleG.japonicusmight be explained by two factors.First,relatively indistinctive sexual dimorphism ofG.japonicusmight be involved in the result(Zhanget al.,2009).In lizards,small sexual size dimorphism is generally related to small differences in home range size between sexes(Coxet al.,2003).Second,reduced home range size of both males and females in introduced area might be in part responsible for the result.In Korea,asG.japonicusis likely an invasive species(Leeet al.,2004),so its microhabitat use might be restricted by local climate conditions.Comparative studies in China or Japan,a potential original habitat,may further clarify nature of home range differences between female and maleG.japonicus.

There was less overlap in Kernel 50 home range compared to MCP home range.In the breeding season,home range of an individual overlapped with 32.4%(MCP)or 13.8%(Kernel 50)of remaining individuals.In previous studies of lizards,a home range overlap of greater than 25% categorized a species to be nonterritorial(Manteuffel and Eiblmaier,2008;Robles and Halloy,2010).Based on this criterion,G.japonicusis non-territorial based on MCP home range,but tends to have core habitat based on Kernel 50 home range,although it might be shared with few others.This pattern has been observed in other gecko species(Kerr and Bull,2006;Stamps,1977),not protecting whole home ranges,but having core area.This result is also consistent with results of previousG.japonicusstudies.In indoor vivaria,G.japonicusshared refuges with a few individuals,but excluded juveniles from the areas(Parket al.,2018).Also,G.japonicusin refuges produced alarm calls only when other geckos closely approached(Jono and Inui,2012),showing exclusively use core habitat at least for a time.

On the other hand,the individual and area overlap ratio of both MCP and Kernel 50 home range was greater in the breeding season,and the ratios of males were greater than those of females.Furthermore,inter-sexual ratios of MCP home range individual overlap tended to be greater than intra-sexual overlap ratios during breeding season(P=0.013,Table S2,Figure S1)although such a trend was not seen during non-breeding season.These results suggest that females and males meet multiple individuals of opposite sex,and that males or females actively seek multiple mates during the breeding season.These results imply that the reproductive system ofG.japonicusis likely polygamous,as found in other lizard species(Stamps,1977).Nevertheless,overall verification of reproductive system can be done by analyzing multiple paternity in offspring using appropriate molecular markers(Choet al.,2018).

In conclusion,G.japonicuswere commonly found in both artificial structures and adjacent natural trees as microhabitat.In the breeding season,G.japonicusmoved farther distances and used wider home ranges.The daily moved distance and home range were not different between sexes.In breeding season,individual MCP home range overlapped with 32% of remaining individuals,but the overlap ratio of the core home range(Kernel 50)was relatively low as 14%,indicating thatG.japonicusis likely non-territorial,and has a core habitat that is shared with few geckos.Considering home range overlap between sexes in breeding season,the reproductive system ofG.japonicusis likely polygamous.

AcknowledgementsWe thank J.Y.SONG in Korea National Park Service for providing the receiver during the study.This study was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF)funded by the Ministry of Education(2016R1D1A1B03931085)and has been worked with the support of a research grant of Kangwon National University in 2018.This research was conducted within the guidelines and approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Kangwon National University(KW-161128-2).

Appendix

Table S1 Variables which used and analyzed in the study.

Table S3 Summary of the use of different structure types(the number of cases)by the Schlegel's Japanese gecko(Gekko japonicus),which introduced into a suburban city park based on different sex,time of day,and season.

Figure S1 The individual(pooled)overlap ratio of MCP home range between inter-sexual individuals was significantly greater than the ratio between intra-sexual individuals in breeding season(Z=2.48,n=15,P=0.013).Except that,other remaining comparisons between intraand inter-sexual individuals and between males and females were not significant(Ps>0.05).Due to small sample cases,we did not analyze the relationships in non-breeding season.For detailed data,see Supplementary Table S2.

杂志排行

Asian Herpetological Research的其它文章

- Correlation between Climatic Factors and Genetic Diversity ofPhrynocephalus forsythii

- Mating Ethogram of a Video-aided Study of Mating and Parturition in Captive Chinese Crocodile Lizards(Shinisaurus crocodilurus)

- Ecological and Geographical Reasons for the Variation of Digestive Tract Length in Anurans

- Geographical Distribution and Morphological Variability of the Rapid Racerunner,Eremias velox(Pallas,1771)(Reptilia,Lacertidae)in the Eastern Periphery of Its Range

- Description of a New Species of Amolops(Anura:Ranidae)from Tibet,China

- Molecular Cloning,Characterization and Sequence Analysis of KCNQ4 in Large Odorous Frog,Odorrana graminea