THE ATHENIAN MONEY SUPPLY IN THE LATE ARCHAIC AND EARLY CLASSICAL PERIOD*

2019-12-26AlainBresson

Alain Bresson

The University of Chicago

August Boeckh is famous for his monumental Staatshaushaltung der Athener, the first edition of which appeared in 1817.1Boeckh 1886.Around the same time, in the Abhandlungen of the Berlin Academy of 1814-1815 (the volume actually appeared in 1818), he also published a fascinating essay on the Laurion mines, the first monograph devoted to the question.2Id. 1814-1815 [1818].On the basis of the information that was available to him, Boeckh’s essay covered every aspect of the question, from the description of the Laurion district (based on the reports of ancient writers as well as those of early modern and modern travelers and geographers) to the legal questions relating to the exploitation of the mines, with a final short analysis of Xenophon’s Poroi. He did not neglect the technical questions of the processing of ore, overlooking neither the question of the quantities of metal produced in the mines, nor that of the profits that could be made from their exploitation.

This paper seeks to contribute to a debate that was opened by Boeckh in his pioneering work. As was already observed by him, it is clear that the silver produced at the Laurion mines at the end of the Archaic period and over the two centuries of the Classical period was a major factor in the transformation of the city. But per se quantity matters. One of the main issues that remains to be solved is of course grasping how much silver was actually produced by the Laurion mines. No less important is the subsidiary matter of how much silver was actually available to the Athenians (or, more precisely, both the Athenian state and individual Athenians). The goal of this study is to produce a first estimate of the money supply in Athens by combining an analysis of (a) the quantities of metal produced by the Laurion mines, of (b) the attrition of these quantities, and (c) of the export from Athens of precious metal to pay the various public or private expenses of the Athenians.3Regarding questions pertaining to the role of the state and its relationship with the mines and its role as regulator, it will suffice to refer to the works contributed by Christophe Flament and Armin Eich, respectively, found elsewhere in this volume.

The Laurion mines and the money supply

It is obvious that in Athens the money supply was directly linked to the existence of the Laurion mines. In Aeschylus’s Persae, presented before an Athenian audience in 472 BC with Pericles as chorēgos, the dialogue between Queen Atossa and the chorus puts it plainly. When Atossa asks about the resources of the Athenians (v. 237): πλοῦτος ἐξαρκὴς δόμοις; “Is there sufficient wealth in their stores?,” the chorus answers (v. 238): ἀργύρου πηγή τις αὐτοῖς ἐστι, θησαυρὸς χθονός, “Of silver they possess a veritable fountain, a treasure chest in their soil.”4Trans. Loeb. See also Xen. Vect. 1.5: καὶ μὴν ὑπάργυρός ἐστι σαφῶς θείᾳ μοίρᾳ· πολλῶν γοῦν πόλεων παροικουσῶν καὶ κατὰ γῆν καὶ κατὰ θάλατταν εἰς οὐδεμίαν τούτων οὐδὲ μικρὰ φλὲψ ἀργυρίτιδος διήκει. “And recollect, there is silver in the soil, the gift, beyond doubt, of divine providence: at any rate, many as are the states near to her by land and sea, into none of them does even a thin vein of silver ore extend” (trans. Loeb).The image of the “fountain” or “spring of silver,” ἀργύρου πηγή, makes it clear that the Athenians were perfectly aware that it was thanks to their silver mines that they had been able to become a city of the first rank in Greece, and knew that this silver built the fleet of 200 ships allowing them to defeat the Persians. Without the silver-born victories in the Persian wars, the destiny of Athens would have been quite different. This raises the question of when the process of expanding production in the Laurion mines began.

The mines in southern Attica had been exploited since the Mycenaean period.5Gill 2010.But it was only when the Athenians discovered the so-called “third contact” that things changed radically.6On the geological aspect, see Morin and Photiades 2005, and the discussion in Davis 2014a, 261.The new mines went far below the veins exploited hitherto, with shafts commonly 20-50 meters deep, or more. On the basis of Herodotus (7.144.1-2) stating that Themistocles had persuaded the Athenians to build a navy for a war against Aigina in 483 BC rather than sharing the mine production revenue among themselves, it has long been thought it was only a few years before that date that the process of expanding the Laurion mines had begun.7The dossier of sources, which includes the Aristotelian Athenaion Politeia (22.7), is complex and contradictory. The exact amount of money at stake is disputed: see Kroll 2009, 206, n. 6; Van Wees 2013, 64-66, and Davis 2014a, 267-269. See also below pp. 137-141.In fact, as proven by Olivier Picard, given the time necessary to dig the mine shafts, build the refining installations and, most importantly, buy the slaves who worked in the mines, it necessarily started several decades earlier in order to reach a level corresponding to the situation of the 480s BC.8Picard 2001.Clearly, it must have been as early as the 520s BC that the new exploitation of mines began.

One thing is certain: mining became a major activity in the Athenian economy. The landscape in the region of Thorikos and Sounion in southern Attica was radically transformed. It is no exaggeration to compare it with that of a modern industrial landscape: the surface is still scarred by the remains of washing basins, cisterns, mills and the other installations necessary to purify and mill the ore, and then to process it, first to extract the lead from the galena, then to separate the silver from the lead by cupellation. As we now see them, many of these facilities are to be dated to the fourth century. The shafts go deep into the ground and then open out into galleries whence the galena was extracted. The poor ventilation in the galleries, the use of polluting oil lamps, the low-quality tools, the lack of proper mine working support, and the toxic fumes created by the smelting of ore certainly meant that the conditions of the slaves working in the mine district were very poor and translated into high mortality rates.9On the condition of mine workers in general, see Bresson 2017, 187, with references.Members of the ruling elite of Athens did their best not to visit the mining district, it being an unhealthy and unpleasant place.10Xen. Mem. 3.6.12.

Historically, the introduction of the first Wappenmünzen in Athens probably dates back to the decade 545-535 BC.11See Kroll 1981, 30, and the discussion in Davis 2012, 139-140, and 2014b, 347 and n. 34.Here we retain the conventional date of 540. Starting from whatever very low level of activity prevailed before 540 BC, production increased gradually until the 520s and 510s. Then it took off and, within decades, soared upwards. The work of Christophe Flament now allows us to frame the question of the exploitation of the mines and of the monetization of Athens in a fresh perspective.12See Flament 2007a, 29-31 and 2007b, 241-253, with id. in this volume.Through a detailed examination of the issues linked to the exploitation of the mines and to Athenian monetization, Flament has emphasized the challenge of estimating mine productivity, and ultimately of Athenian coinage output. Given the mass of coins produced, it is impossible - for now at least - to provide a complete die analysis, a problem that is encountered again, much later, with Roman denarii.13Flament 2007a, 25-29, and 2007b, 16-19.

The spectacular growth in the volume of coin production is confirmed by the evolution of types. Minting apparently started in the decade following the final return of Peisistratos in 546 BC.14Davis 2014a, 258-259.Initially, in the first two decades of minting, with the first series of the so-called Wappenmünzen, there were no fixed types, and fourteen different obverses are recorded. The coins minted were didrachms, rare drachms, and many obols and hemi-obols. Then after c. 525 BC, a new series of Wappenmünzen was struck, with the Gorgon-type obverse, hence the name of Gorgoneion assigned this coin. For the first time, a reverse type was introduced (first a facing bull’s head, then followed by the facing head and paws of a lion). The Gorgoneia phase is also characterized by a new and heavier denomination, a17Kroll 1981; Flament 2007a, 27-28..30 g tetradrachm.15Flament 2014a, 9-23. The interesting suggestion of Davis (2014b) that the wheel fractions were coined in parallel to owls until the Persian Wars will have, however, to be confirmed by further analysis.In this period, Athens also minted a few electrum coins, but evidently in very limited quantities.16Davis 2015.Finally, perhaps still under the tyranny in 514 BC - although a later date cannot be excluded - the henceforth stable types of the head of Athena on the obverse and owl on the reverse were introduced.17They assured the easy identification of these coins as Athenian, probably deliberately as these coins (and indeed already the Gorgoneia) traveled far further abroad than the initial series of Wappenmünzen. Later, in the 460s BC, when metal production reached a new high (or perhaps also using metal out of the booty from the battle of Eurymedon), the mint also struck decadrachms, very heavy coins of 43 g.18For the decadrachms, Fischer-Bossert 2008, 18-29, suggests a starting date c. 469-465 BC and a final date c. 460 BC.

It is clear that there was a steep rise in the production of Laurion. But estimating the actual volumes of production remains a challenging task. At present, for want of die studies of the Athenian mint, for the late Archaic period the discussion has focused on an information provided by Ps.-Aristotle (Ath. Pol. 22.7). One hundred talents came into the state treasury from the new seams at Maroneia (in the Laurion district). The Athenians wanted to share among themselves but Themistocles persuaded them to use to build a fleet instead. We do not know what proportion of the production went into the state treasury, and we do not know whether this number - if it can be trusted at all - corresponds to one year of production or to several, and if so, to how many. More broadly and for the whole late Archaic and Classical period, as we saw recent research has produced estimates based on the relative volume of the various series of Attic owls, on the conditions of production, on the quantities of fuel needed and on the number of slaves and their cost.19In 1970, Chester Starr (suggested a production increase from c. 11.5 talents for the first Wappenmünzen to 19 talents for the second series, then to about 155 talents for the owls issued between 510 and 475 BC and finally 470 talents for the period 474 and 449 BC. For Constantin Conophagos (1980, 138-152 and 341-354, esp. 354), Laurion produced c. 700 talents in the fifth century. Christophe Flament (2007b, 245-247) has shown that production must have exceeded 1,000 talents after 450 BC. John Kroll (2009, 196) has suggested volumes significantly higher: 2,400 talents in 483/482 BC (on the basis of the 100 talents of Herodotus and a state tax of 4.17%) and again at the same level in the third quarter of the fifth century. Davis (2014a, 273) is implicitly thinking of c. 550 to c. 700 talents on the basis of 50 talents per annum for the state and a collection rate of 4.17% for the tax and a minting fee of three to five per cent.The estimates provided below are thus only “reasonable guesses” that allow us to build models and conduct analyses of the dynamics of production. These numbers will have to be modified when die studies produce reliable information on the production of Laurion in the late Archaic period.20See now the project developed by Kenneth Sheedy, Damian Gore and Gil Davis (Sheedy, Gore and Davis 2009).For the period that follows the Second Persian War, the situation is even more uncertain and we will use two numbers to test two different hypotheses.

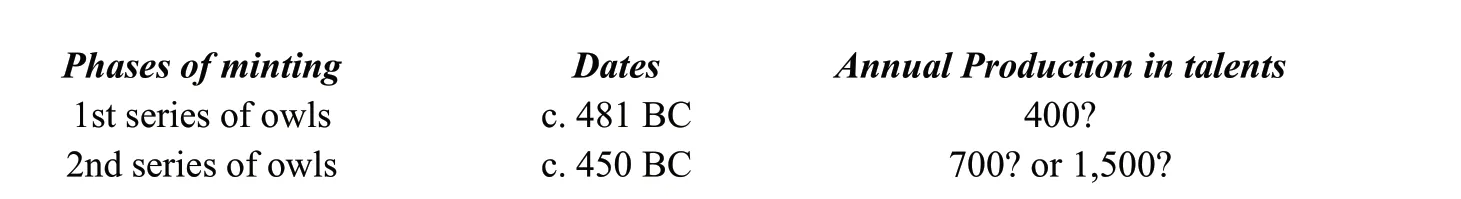

Table 1: Phases of the development of Attic coinage

The development in coin production demonstrates the remarkable increase in metal production in less than a century. Of course, although we know that an extraordinarily high number of obverse dies has been observed, these numbers are only estimates. A smooth growth provided by an exponential function might convey the illusory impression of a regularity in the increasing production. The detail of production development must have been more chaotic, as it was based on chance finds of new and highly productive veins, as at Maroneia. Nonetheless, the general trend remains clear. Still, it is necessary to move a step further and calculate the volumes that were both produced and accumulated in order to arrive at an estimate for the money supply. To do so, the period 540-450 BC is divided into two sub-periods, 540 to 481 and 479 to 450 BC. In 480 and 479 BC, Athens was occupied by the Persians, suffered heavy destruction and, therefore, had no mining activity.

In the period 540 to 481 BC (sixty years), for the sake of calculation we assume a production of 1 talent per year in 540 BC, ending with a production of 400 talents in 481 BC, the year before the Persian invasion. In between, we assume that the yearly production piincreased exponentially, according to the equation pn= pi(1+ρ)nwith pnis the final value (400), the rate of increase ρ = 10.69% and the number of years n = 59. The annual multiplier is 1.1069, with 1.106959≃ 400.

This allows us to calculate the sum of all metal produced and coined (assuming that the bulk of it was coined, even if some of it must inevitably have been sold as ingots to produce jewels, vessels or as export items, but, no doubt, comprising a comparatively minor share of the total).

However, every year a certain number of the coins produced will have been lost: some coins will have been stashed away by their owners, and after their untimely deaths the coins hoarded will not all have been recovered by their heirs; some coins will also have been lost at sea; some will have been lost during episodes of civil or foreign wars, fires, earthquakes, etc. If we apply a 2% annual attrition rate to each year’s production (pi), this allows us to calculate:21For an attrition rate of 2%, see Patterson 1972. With this attrition rate, after one hundred years the initial production of a given year is reduced to c. 13% of its initial amount, with (1 - 0.02)100 ≃ 0.13. As defined, the attrition is that of the money supply, not the loss weight of the individual coins, which is commonly far lower (see Velde 2013).

1) the remaining money supply volume after attrition (pai) corresponding to each year of production, with pai= pi(0.98n), with n (60 → 1) for the period 540 to 481 BC, and n (91 → 1) for the period 540 to 450 BC;

2) the cumulative totals of the remaining money supplies after attrition for the periods 540 to 481 BC and 540 to 450 BC:

Following the second Persian War, the second period of production covers the years 478 to 450 BC. Although Athens had badly suffered from the war, it had also greatly benefitted from the victory. Because of the number of prisoners, the slave supply must have been abundant. With Robert Garland, we must also assume that the slaves were evacuated from the mines along with the rest of the population.22See Garland 2017, 50.It would have been foolish to leave them behind, as they could have benefited the Persians as a workforce for camp or fortification building, or to row in their navy. Besides, in 478 BC it was not a question of restarting mining activity from scratch but to relaunch a process that had just been interrupted two years before. There must have been destruction in the mining district, but given the technologies at stake the installations could be rebuilt or repaired rather quickly. We assume that production resumed as early as 478 BC with a yield of one talent, but with a very high growth rate, growing exponentially with an annual multiplier of 1.981. With a production almost doubling every year, it can be estimated that ten years later, in 469 BC, it had already reached 470 talents (1.9819≃ 470). This fits with the model of very high production in the 460s, a decade when immense volumes of both tetradrachms and decadrachms were produced, the latter being the heaviest coins ever produced by the Athenian mint. Then, we assume that the growth rate decreased (which can be easily justified in economic terms by a law of increasing costs: the costs of maintaining and feeding more slaves on the same site grew, the costs of importing wood and charcoal also grew, etc.). The question is: what was the production level around 450 BC? Was it 700 talents? Or much more, for instance at 1,500 talents? Below we test both hypotheses.

With the same method as that which is described for the period 540-481 BC we also calculate the corresponding total amounts remaining after attrition for the period 478-450 BC according to the two production hypotheses previously mentioned (maximum production of 700 talents, multiplier 1.0213, or 1,500 talents in 450 BC, multiplier 1.063). Once these figures are calculated they must be added to the total production (after attrition down to 450 BC) of the years 540-481 BC, to get the potential money supply in 450 BC.

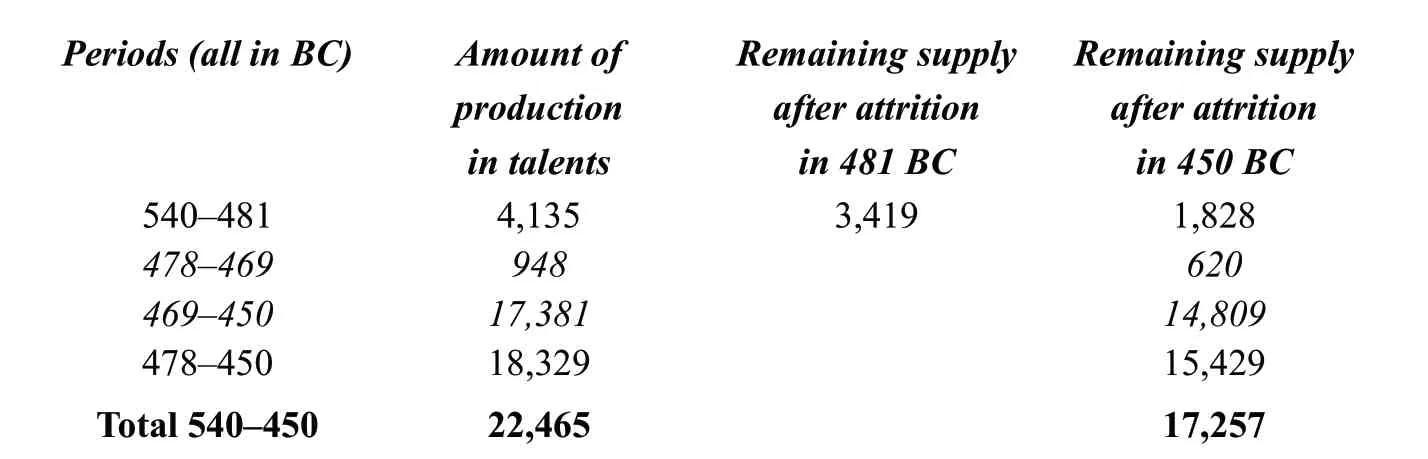

The results are summarized in Tables 2 and 3:

Table 2: Production of the Laurion mines in the period 540-450 BC, hypothesis 1 maximum 400 talents in 481 BC and 700 talents in 450 BC

Table 3: Production of the Laurion mines in the period 540-450 BC, hypothesis 2 maximum 400 talents in 481 BC and 1,500 talents in 450 BC

The money supply and the Athenian treasury

For the first period the inevitable conclusion is that in late Archaic Athens mining activity grew at a very significant yearly rate, here estimated at 10% in the framework of our hypothesis. This exceptional growth rate (as compared to what we may assume for growth rates in other production sectors) was obviously made possible by reinvesting part of the mining profits into the very same profitable activity, resulting in a process of self-feeding capital. We have also seen that in order to reach the very high levels of production of the 460s, after restarting from nil, production inevitably grew by a yearly rate of almost 100% for a decade, which could be called the decade of reconstruction. We have kept a 2% attrition rate for the years 480-479 BC, which of course must be far below what really happened during these two traumatic years.

The resulting calculated amounts, 3,419 talents for 481 BC and 11,702 or 17,257 for 450 BC, are an indication of massive growth of the money supply between 540 and 450 BC. The Athenians probably used weighed silver bullion as money before the introduction of coinage, as has been suggested for the period of the reforms of Solon in the early sixth century, although admittedly the question is still heavily debated.23Kroll 1998, 2001, 2008 and 2012 arguing in favor of the usage of weighed bullion in Solonian Athens, Davis 2012 against it.What remains certain is that in the 540s the amount of available silver was still very low, which can be corroborated by the absence in Athens, and in Greece in general, of hoards similar to the Hacksilber hoards that can be found in fairly large number in western Syria in the Early Iron Age and Archaic period.24Thompson 2003, 2011; Thompson and Skaggs 2013.By contrast, in 481 BC the money supply in Athens numbered in the thousands of talents. But the most dramatic growth was still to come in the 470s, 460s, and 450s, the money supply reaching a new high, of well over ten thousand talents.

But if the calculated amounts certainly give us an indication of the evolutionary trend for the money supply, one should not think that they correspond to the money supply actually available in Athens for years 481 and 450 BC, respectively. Athens was not a closed society or closed market. In the Archaic period, the city had always been deeply connected to the rest of the Greek and Mediterranean world. Its port was very active, and the creation of the Piraeus by Themistocles between the two Persian Wars (even if certainly the main process of construction of the new port postdates the second Persian War) offered new facilities that provided new opportunities for traders and foreign exchange in general.25Thuc. 1.93.3-7 and Plut. Them. 19. See Garland 2001, 14-20.Athens became rich in the late Archaic and early Classical period. Its population also grew rapidly. There were seemingly 30,000 citizens in 480 BC and perhaps 50,000 at the start of the Peloponnesian War. The total population then reached perhaps for a brief period a maximum of around 330,000 inhabitants. In the fourth century, with 30,000 citizens and with a total population that probably was not above 250,000 inhabitants, the dependence on grain imports from outside of Attica was around 73%.26For these numbers for the population of Athens, cf. Bresson 2016, 409. For the dependency on grain, see ibid., 410-411 anPart of the imported grain came directly from Athenian territories in the Aegean and did not constitute a real import (as part of it corresponded to a tax in kind levied in these territories), reducing the dependence to foreign grain to c. 60%. Beyond grain, Athens needed a wide range of other products to feed its population, provide clothing, and supply equipment for its mines, shipyards and workshops in general, not to mention the luxury goods always in high demand among the elite. Wine, oil, wool and linen, wood, charcoal, iron, copper, and slaves are but a few examples from the long list of “goods” it had to import to keep its system working.27See Van Alfen 2016 for the flow of goods between the Aegean and the Levant, and Bresson 2016, 73, 348, and 351-358.

In exchange, Athens could export its highly valuable marble, honey and certainly a variety of handicrafts such as furniture, ceramics or cloths. That being said, its main export by far was the product of its “industrial district:” silver from the Laurion mines. The Wappenmünzen, especially the fractions, were obviously minted for domestic or regional use (they are also found in Euboea).28See IGCH 2 (Athens: Wappenmünzen and Eretria), 3 (Euboea: Chalcis and Wappenmünzen), 5 (Eleusis: Eretria and Attic Wappenmünzen), 9 (Eretria: Eretria and Wappenmünzen), 10 (Euboea: Eretria and Wappenmünzen) and 12 (Athens: Wappenmünzen and owls). See Ross Holloway 1999, 6, and Van Alfen 2012, 90-91.They rarely reached distant markets.29See however the following hoards:- for the Levant, Jordan (IGCH 1482, c. 445 BC) one Wappenmünzen obol for one decadrachm, 10 owl tetradrachms and 18 fragments of tetradrachm and one fragment of drachm;- for Egypt, Sakha (IGCH 1639, early fifth century), two Wappenmünzen didrachms, with no owl; Benha el-Asl (IGCH 1640, dated probably to c. 490-485 BC), with one Gorgoneion tetradrachm, five owl tetradrachms and four fragments; Fayum (IGCH 1646, c. 460 BC), one Wappenmünzen didrachm, with no owl; Asyut (IGCH 1644, closed apparently c. 460 BC but with the main accumulation phase ending c. 477 BC), with one wheel-didrachm and one Gorgoneion tetradrachm for 163 late Archaic owls;- for Italy, Taranto (IGCH 1874; CH 7, 10; CH 10, 365; late sixth century), with one wheel-didrachm and one Gorgoneion tetradrachm, for five Archaic owls (Kroll 1981, 15, n. 47, and Kroll and Waggoner 1984, 328).One can agree with Peter Van Alfen (2012) that the Gorgoneia began to find some success in outside markets. The volumes exported are never impressive because, as compared to the owls, the volumes produced were very low.With the massive increase of production at Laurion, silver became an export item. The new owl tetradrachms were minted at their full standard weight and consistently with an almost pure silver, which made of them the perfect product for export.30Davis, Sheedy and Gore forthcoming; see also Kroll 2011.These exports of Attic silver coinage are well attested by the presence of Attic coins in the hoards of the Mediterranean world both in the West and in the East already before the Second Persian War.31For the Levant and Egypt, see Fischer-Bossert 2008; Buxton 2009; Van Alfen 2016; Duyrat 2016, 307-325.The process accelerates after the Second Persian War, when the Attic tetradrachms normally account for a majority of the coins in the fifth century hoards of the Eastern Mediterranean. It is clear that a large quantity of silver coins left Athens to pay for its massive imports. In the Poroi (3.1-2), Xenophon famously mentions that in his time (c. 355 BC), at Athens, foreign merchants could export good quality coinage and make a profit out of the operation. The remark would also apply to the fifth century. This is the peculiarity of commodity money, that is, money which is primarily a good having to be materially produced, production of which itself is predicated on the chance of having precious metal ores on one’s territory. As a good, silver money was always in high demand, everywhere and by everyone.

For political reasons, the many military expeditions launched by the Athenians in this period inevitably also entailed considerable exports of Attic coinage. Admittedly, from 478/477 BC onwards Athens also levied a tribute on its allies (and various other dependent territories), which means that part of the metal that was exported came back to Athens. According to Thucydides (2.13.3) in the 430s the tribute amounted to six hundred talents. But there now seems to be a consensus that in peacetime the tribute amount managed to cover the daily expenses of the Athenian fleet, and at best allowed a limited accumulation in the treasury of the Allies.32Gabrielsen 1994, 114-117, and the detailed assessment of Flament 2007b, 120-125.When a major expedition was launched, the tribute being received would never be sufficient to fund it (and quite far from it). Thus, for instance, for the expedition against Potidaia between 432 and 430/429 BC, the city had to draw on its reserves (Thuc. 2.13.3).

It is thus clear that, both for economic and political reasons, Athens exported large quantities of the silver it produced. The frequent reminting of Attic coinage into local coins conceals the massive character of these Attic coinage exports, and when metal analyses can be made on the coins of these various mints during this period, they commonly reveal that their metal comes from Laurion. Herodotus (3.57-58) tells us that Siphnos also provided gold and silver, and thus for a short period that island may have been a large provider of metal.33See Sheedy 2006, 51-53.Then the Laurion mines triumphed. An interesting case is provided by Aegina, Athens’ archrival until it had to submit in 456 BC. On the basis of analyses performed on the Aeginetan specimens from the Asyut hoard (c. 477 BC), that is on coins corresponding to the late Archaic series of Aegina, the main source of metal for the mint of Aegina in this period was Laurion. There were also traces corresponding to Thracian sources, Thrace having been the most important precious metal producer in the Aegean region in the late Archaic period before the spectacular growth of the Laurion production.34On the origin of the metal of the Aeginetan coins, see Figueira 1981, 144-149,In the Levant also, in the second half of the fifth century or in the fourth century, Philistine and Edomite coins as well as locally minted tetradrachms imitating Attic owls were in all probability minted using silver from Laurion.35Gitler, Ponting and Tal 2008, and Ponting, Gitler and Tal 2011.This massive export of Attic coinage fits perfectly with the phase of a dramatic new increase in the production of the Laurion mines after 478 BC. Conversely, because of the tribute and other taxes probably, some silver not originating from Laurion also found its way to the Athenian mint, but the volumes remained low: of a sample of 68 owls analyzed by Flament, only c. 7% were minted from non-Laureotic silver36Flament 2007c; Kroll 2009..

What still remains to be answered is the question of the total amount of exported Attic silver. On the basis of the previous analyses, it is clear that at least after the Second Persian War, hundreds of talents in Attic tetradrachms or decadrachms were exported from Athens - but how much? In the fourth century, the grain imports coming from non-Athenian territories can be estimated at 760,000 medimnoi. At the low price of two drachms per medimnos (as the price of the grain bought on foreign markets, not the price at which it was sold in Athens), this corresponds to a total of 1,520,000 drachms or 253 talents, which can be rounded off to 250 talents as a minimum. If we add the value of all the other imports that were not balanced by goods produced in Athens and the money spent abroad in military expeditions, it seems reasonable to think that it amounted to a total of c. 400 talents leaving Athens every year, which would correspond to 26% of the supposed production of silver in 450 BC (1,500 talents). In the framework of this hypothesis, we should thus admit that on average and over time the Athenians exported around one fourth of their silver production. This is certainly a low estimate for net export of metal and actual numbers might have been higher, even much higher, but a low estimate is certainly best to test the model of a maximum yearly production of 1,500 talents in 450 BC. Before the middle of the fifth century the production of silver was lower and the population less numerous, but imports of grain were already needed and the export ratio may have been pretty similar; we also saw that the first series of Wappenmünzen were exported to distant markets in small quantities only, and anyway in quantitative terms their contribution to the Athenian coinage in the period 540-440 BC is negligible; it is with the late Archaic owls that massive exports of Attic silver began. On the basis of the “high amount of production hypothesis” (hypothesis 2) of 1,500 talents of silver produced in 450 BC, 26% would represent 4,487 talents. This would have left 12,770 talents actually available as a money supply in Athens in 450 BC.

These calculations involve a number of estimates, yet in each instance one can observe that the item being estimated (for instance, the existence of massive exports of Attic silver) is corroborated by textual or archaeological sources - only numbers are missing. Now the question is: can these estimates be tested against authentic sources? How do they help us to assess the financial, economic and social situation of Athens during these years? And what is the point in building such models when the actual data is missing?

We have at least one number, which is provided by Thucydides, in the speech delivered by Pericles before the Athenian assembly in 431 BC, just before the beginning of the war against the Peloponnesians:37Thuc. 2.13.2-4 (trans. Loeb): τά τε τῶν ξυμμάχων διὰ χειρὸς ἔχειν, λέγων τὴν ἰσχὺν αὐτοῖς ἀπὸ τούτων εἶναι τῶν χρημάτων τῆς προσόδου, τὰ δὲ πολλὰ τοῦ πολέμου γνώμῃ καὶ χρημάτων περιουσίᾳ κρατεῖσθαι. θαρσεῖν τε ἐκέλευε προσιόντων μὲν ἑξακοσίων ταλάντων ὡς ἐπὶ τὸ πολὺ φόρου κατ᾿ ἐνιαυτὸν ἀπὸ τῶν ξυμμάχων τῇ πόλει ἄνευ τῆς ἄλλης προσόδου, ὑπαρχόντων δὲ ἐν τῇ ἀκροπόλει ἔτι τότε ἀργυρίου ἐπισήμου ἑξακισχιλίων ταλάντων (τὰ γὰρ πλεῖστα τριακοσίων ἀποδέοντα μύρια ἐγένετο, ἀφ᾿ ὧν ἔς τε τὰ προπύλαια τῆς ἀκροπόλεως καὶ τἆλλα οἰκοδομήματα καὶ ἐς Ποτείδαιαν ἀπανηλώθη), χωρὶς δὲ χρυσίου ἀσήμου καὶ ἀργυρίου ἔν τε ἀναθήμασιν ἰδίοις καὶ δημοσίοις καὶ ὅσα ἱερὰ σκεύη περί τε τὰς πομπὰς καὶ τοὺς ἀγῶνας καὶ σκῦλα Μηδικὰ καὶ εἴ τι τοιουτότροπον, οὐκ ἐλάσσονος ἢ πεντακοσίων ταλάντων.

(The Athenians should) keep a firm hand upon their allies, explaining that Athenian power depended on revenue of money received from the allies, and that, as a general rule, victories in war were won by an abundance of money as well as by wise policy. And he bade them be of good courage, as on an average six hundred talents of tribute were coming in yearly from the allies to the city, not counting the other sources of revenue, and there were at this time still on hand in the Acropolis six thousand talents of coined silver (the maximum amount had been nine thousand seven hundred talents, from which expenditures had been made for the construction of the Propylaea of the Acropolis and other buildings, as well as for the operations at Potidaea). Besides, there was uncoined gold and silver in public and private dedications, and all the sacred vessels used in the processions and games, and the Persian spoils and other treasures of like nature, worth not less than five hundred talents.

The total silver reserves possessed by the Athenian state had thus reached 10,200 talents in 450 BC.38Pericles added (Thuc. 2.13.5) that in last resort the city could use the gold plate adorning the statue of Athena, which weighed 40 talents, the equivalent of 533 talents in silver value with a gold to silver ratio 13 1/3 : 1.Most of it (9,700) consisted of coined silver (ἀργύριον ἐπίσημον), that is, in owls in all likelihood mostly minted from silver from Laurion. But how could such an amount have been accumulated?

It is precisely in this kind of situation that a model proves its usefulness. Thucydides’ number allows us to test the two previously cited hypotheses and proves sufficient to discard the “low production hypothesis” (hypothesis 1), where a maximum production of only 700 talents was reached in 450 BC: after attrition, only 11,702 talents would have been left in 450 BC, and with the inevitable exports of several thousand talents, the total would not have been sufficient to reach the almost 10,000 talents mentioned by Pericles, plus of course the amount left in private hands. Only “hypothesis 2,” with a maximum production of 1,500 talents in 450 BC, is compatible with the amount mentioned by Thucydides. If the estimated 12,770 talents actually available in the city can be trusted and if 10,200 talents were in the city’s public and sacred reserves, this would leave 2,570 talents in private hands. This is perhaps one of the secrets behind the huge accumulation of silver on the acropolis. If, at a minimum, the amount corresponding to the booty from the campaigns against the Persians financed the costly expeditions in the eastern Mediterranean, the Athenians would have been able to keep for themselves part of the profits they made from their taxes. Indeed, if we are to follow Gil Davis, the direct profit from the Laurion mines for the Athenian state represented perhaps but 7-9% of the total value of the production from the mines.39Davis 2014a, 273. If we kept the hypothesis of Davis of a 4.17% tax only and combined it with Flament’s view (2007b, 247-249) that no profit was made from minting, the profit of the state would not exceed 4.17%. However, we have reason to believe that minting, or reminting, was not performed for free: see Bresson 2015 for the case of Ptolemaic Egypt in 258 BC, on the basis of P.Cair.Zen. 59021, ll. 31-34. There, we find that for the merchants who bring their old or foreign coins to the mint for reminting, οὐδεὶς γὰρ τούτων ἔχει οὗ τὴν ἀναφο|ρὰν ποιησάμενος καὶ προσθείς τι κο|μιεῖται ἢ καλὸν. χρυσίον ἢ ἀργύριον | ἀντ’ αὐτοῦ “none of them knows to whom he can refer and after adding a little get back fine gold or silver in exchange;” ll. 43-46: καὶ τὸ νό|μ. ι. σ.μα τ.[ὸ] τ.[ο]ῦ. [β]ασιλέως καλὸν καὶ | καινὸν ἦι διὰ παντός, ἀνηλώματ[ος] | μηθενὸς γινομένου αὐτῶι (those in charge of the mint should ensure) “that the royal coinage should always be fine and new, at no expense to the king” (trans. Austin 2006, 535-536, no. 299).But large profits could be made from various taxes, especially from the activity of the Piraeus, which was experiencing a massive upsurge during this period.40This is the assumption of Davis 2014a, 273-274, which seems convincing.

Another question is how such an amount could be accumulated, given that since 478 BC Athens had been continuously fighting in various operational theaters, which must have entailed considerable expenditure.41Bresson 2010, 391.Tribute from allies could hardly have been sufficient to provide for the huge expense of the repeated expeditions, often in distant regions, like the straits, southern Asia Minor, Cyprus and Egypt. At the same time, booty could have supplemented revenue, and certainly after the victories of the Second Persian War very large profits were made from the campaign at Eion, Byzantion, and above all from the victory at the Eurymedon, as well as probably from the victories of the initial phase of the campaign in Egypt and later in Cyprus. The Greeks knew that they could make a good deal of money not only from the plundering of enemy camps, but also by ransoming men, as large numbers of captives were made during these campaigns, such as when the Persians suffered a crushing defeat at the Eurymedon.42Miller 1997, 38-41.

The seemingly low amount of money left in private hands, a little over 2,500 talents in the hypothesis presented above, may seem puzzling. But most Athenians certainly had only a few drachms in cash in reserve, or at best a few hundred drachms for those belonging to the “middle class.” Only the very wealthy could have had reserves in cash of several talents. In 403 BC, the metic Lysias, who belonged to a rich family that owned a shield workshop, had at home a reserve in precious metal worth (around) five talents 933 drachms, most of it in cash.43Lys. 12.8-16 (Against Eratosthenes). Lysias had in his home (12.11) three talents of silver, four hundred Cyzicenes, a hundred darics and four silver cups. A Cyzicene was worth 24 drachms five obols (Eddy 1970, with the discussion of Figueira 1998, 525-527) and 400 Cyzicenes were worth one talent 3,933 drachms and two obols. The daric was worth (almost) 26 Attic drachms (Figueira 1998, 526), and 100 were worth c. 2,600 drachms. We assume that the cups were standard 100-drachm vessels. The total is 30,933 drachms or five talents and 933 drachms.Admittedly, this was at the end of the Peloponnesian War, at a time when the Athenian treasury was itself completely empty and when private fortunes must have been severely depleted. However, one should keep in mind that it was not in the interest of the rich to keep their money idle. Lysias might well have had lent the larger part of his cash, as wealthy Athenians commonly did.44See Millett 1991, 166-171, and Shipton 2000, 13. We will come back to this question in another study.A super wealthy man like Kallias Lakkoploutos was said to have possessed 200 talents, though we do not know what proportion was in cash.45Davies 1971, 258-261, s.v. Kallias II.This is not incompatible with an amount of cash in private hands of only c. 2,500 talents, although we may suspect that the actual amount might have been somewhat higher.

Conclusion

This study has provided an estimate of the Athenian money supply between c. 540 and 450 BC. A joint analysis of silver production, attrition of the money supply and exports of silver shows that in order to fit with the only incontrovertible number we have, that of the reserves on the Athenian acropolis in 450 BC, we must conclude that the actual amount of silver production in Laurion was at least in the range of 1,500 talents in 450 BC (the “high count”), not 700 (the “low count”).

The money supply in Athens thus experienced a dramatic expansion between c. 540 BC and the second half of the fifth century. There is no doubt that this transformation triggered a process of population growth and of economic growth, as well as profound transformation in social relations. The link between these two aspects will be the object of a further study.

Bibliography

Austin, M. M. 2006.

The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest: A Selection of Ancient Sources in Translation. 2nd ed. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press.

Boeckh, A. 1886.

Die Staatshaushaltung der Athener. 3rd ed. (1st ed. 1817). 3 vols. Berlin: Reimer.— — 1814-1815 [1818].

“Über die Laurischen Silberbergwerke in Attika.” Abhandlungen der historischphilologischen Klasse der Königlich-Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften: 85-140.

Bresson, A. 2010.

“Revisiting the Pentekontaetia.” In: V. Fromentin, S. Gotteland and P. Payen (eds.), Ombres de Thucydide. Bordeaux: Ausonius, 383-401.— — 2015.

“The Cost of Getting Money in Early Ptolemaic Egypt: The Case of Pap.Cair.Zen. I 59021 (258 BCE).” In: D. Kehoe, D. M. Ratzan and U. Yiftach (eds.), Transactions Costs in the Ancient Economy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 118-144.— — 2016.

The Making of the Ancient Greek Economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.— — 2017.

“Anthropogenic Pollution in Greece and Rome.” In: O. Cordovana and G. F. Chiai (eds.), Pollution and the Environment in Ancient Life and Thought. Stuttgart: Steiner, 179-202.

Buxton, R. F. 2009.

“The Northern Syria 2007 Hoard of Athenian Owls: Behavioral Aspects.” American Journal of Numismatics 21: 1-27.

Conophagos, C. 1980.

Le Laurium antique et la technique grecque de la production de l’argent. Athens: Ekdotike Hellados.

Davies, J. K. 1971.

Athenian Propertied Families. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Davis, G. 2012.

“Dating the Drachmas in Solon’s Laws.” Historia 61: 127-158.— — 2014a.

“Mining Money in Late Archaic Athens.” Historia 63: 257-277.— — 2014b.

“Where are All the Little Owls?” In: A. Matthaiou and R. Pitt (eds.), Athenaion Episkopos: Studies in Honour of H. B. Mattingly. Athens: Ellenike Epigraphike Etaireia, 339-347.— — 2015.

“Athenian Electrum Coinage Reconsidered: Types, Standard, Value, and Dating.” Numismatic Chronicle 175: 1-9.

Davis, G., Sheedy, K. and Gore, D. forthcoming.

“Significance of the Weight, Size and Purity of Archaic ‘Owl’ Tetradrachms.” In: K. A Sheedy and G. Davis (eds.), Mines, Metals, and Money: Ancient World Studies in Science, Archaeology and History. Metallurgy in Numismatics 6. forthcoming.

Duyrat, F. 2016.

Wealth and Warfare: The Archaeology of Money in Ancient Syria. New York: American Numismatic Society.

Eddy, S. 1970.

“The Value of the Cyzicene Stater at Athens in the Fifth Century.” American Numismatic Society Museum Notes 16: 13-22.

Figueira, T. J. 1981.

Aegina. Society and Politics. New York: Arno Press.— — 1998.

The Power of Money. Coinage and Politics in the Athenian Empire. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Fischer-Bossert, W. 2008.

The Athenian Decadrachm. New York: The American Numismatic Society.

Flament, C. 2007a.

Le monnayage en argent d’Athènes. De l’époque archaïque à l’époque hellénistique (ca. 550 - ca. 40 av. J.-C.). Louvain-la-Neuve: Association Professeur Marcel Hoc. — — 2007b.

Une économie monétarisée: Athènes à l’époque classique (440-338). Contribution à l’étude du phénomène monétaire en Grèce ancienne. Louvain-la-Neuve: Peeters.— — 2007c.

“L’argent des chouettes.” Revue Belge Numismatique 153: 9-30.

Gabrielsen, V. 1994.

Financing the Athenian Fleet: Public Taxation and Social Relations. Baltimore & London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Garland, R. 2001.

The Piraeus: From the Fifth to the First Century B.C. 2nd ed. Bristol: Bristol Classical Press.— — 2017.

Athens Burning. The Persian Invasion of Greece and the Evacuation of Attica. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Gill, D. W. J. 2010.

“Amenhotep III, Mycenae and the Laurion.” In: N. Sekunda (ed.), Ergasteria: Works Presented to J. E. Jones on his 80th Birthday. Gdańsk: Gdańsk University, 21-35.

Gitler, H., Ponting, M. and Tal, O. 2008.

“Metallurgical Analysis of Southern Palestinian Coins of the Persian Period.” Israel Numismatic Research 3: 13-27.

Kroll, J. H. 1981.

“From Wappenmünzen to Gorgoneia to Owls.” American Numismatic Society Museum Notes 26: 1-26.— — 1998.

“Silver in Solon’s Laws.” In: R. Ashton and S. Hurter (eds.), Studies in Greek Numismatics in Memory of M. J. Price. London: Spink, 225-232.— — 2001.

“Observations on Monetary Instruments in Pre-coinage Greece.” In: M. S. Balmuth (ed.), Hacksilber to Coinage: New Insights into the Monetary History of the Near East and Greece. New York: American Numismatic Society, 77-91.— — 2008.

“The Monetary Use of Weighed Bullion in Archaic Greece.” In: W. V. Harris (ed.), The Monetary Systems of the Greeks and Romans. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 13-37.— — 2009.

“What about Coinage?” In: J. Ma, N. Papazarkadas and R. Parker (eds.), Interpreting the Athenian Empire. London: Duckworth, 195-209.— — 2011.

“Minting for Export: Athens, Aegina, and Others.” In: T. Faucher, M.-C. Marcellesi and O. Picard (eds.), La circulation monétaire dans le monde grec antique. Athens: École Française d’Athènes, 27-38.— — 2012.

“The Monetary Background of Early Coinage.” In: Metcalf 2012, 33-42.Kroll, J. H. and Waggoner, N. M. 1984.

“Dating the Earliest Coins of Athens, Corinth and Aegina.” American Journal of Archaeology 88: 325-340.

Metcalf, W. E. 2012.

The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Coinage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Miller, C. 1997.

Athens and Persia in the Fifth Century B.C.: A Study in Cultural Receptivity. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press.

Millett, P. 1991.

Lending and Borrowing in Ancient Athens. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press.

Morin, D. and Photiades, A. 2005.

“Nouvelles recherches sur les mines antiques du Laurion (Grèce).” Pallas 67: 327-358.

Patterson, C. C. 1972.

“Dwindling Stocks of Silver, and their Relevance to Studies of the Metal Contents of Silver Coinage.” In: E. T. Hall and D. M. Metcalf (eds.), Methods of Chemical and Metallurgical Investigation of Ancient Coinage. London: Royal Numismatic Society, 149-152.

Picard, O. 2001.

“La découverte des gisements du Laurion et les débuts de la chouette.” Revue Belge Numismatique 147: 1-10.

Ponting, M., Gitler, H. and Tal, O. 2011.

“Who Minted those Owls? Metallurgical Analyses of Athenian-Styled Tetradrachms Found in Israel.” Revue Belge Numismatique 157: 117-134.

Ross Holloway, R. 1999.

“The Early Owls of Athens and the Persians.” Revue Belge Numismatique 145: 5-15.

Sheedy, K. A. 2006.

The Archaic and Early Classical Coinages of the Cyclades. London: Royal Numismatic Society.

Sheedy, K., Gore, D. and Davis, G. 2009 [2012].

“‘A Spring of Silver, a Treasury in the Earth’: Coinage and Wealth in Archaic Athens.” Ancient History: Resources for Teachers 39/2: 248-257.

Shipton, K. 2000.

Leasing and Lending: The Cash Economy in Fourth-Century BC Athens.

London: Institute of Classical Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London.

Starr, C. G. 1970.

Athenian Coinage 480-449 B.C. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Thompson, C. M. 2003.

“Sealed Silver in Iron Age Cisjordan and the ‘Invention’ of Coinage.” Oxford Journal of Archaeology 22, 67-107. — — 2011.

“Silver in the Age of Iron: An Overview.” In C. Giardino (ed.), Archeometallurgia: dalla conoscenza alla fruizione. Atti del convegno Cavallino, Lecce, 22-25/05/2006. Bari: Edipuglia, 121-132.

Thompson, C. M. and Skaggs, S. 2013.

“King Solomon’s Silver? Southern Phoenician Hacksilber Hoards and the Location of Tarshish.” Internet Archaeology 35: doi:10.11141/ia.35.6.

Van Alfen, P. G. 2012.

“The Coinage of Athens, Sixth to First Century B.C.” In: Metcalf 2012, 88-104.— — 2016.

“Aegean-Levantine Trade, 600-300 BC: Commodities, Consumers, and the Problem of autarkeia.” In: E. M. Harris, D. M. Lewis and M. Woolmer (eds.), The Ancient Greek Economy: Markets, Households, and City-States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 277-298.

Van Wees, H. 2013.

Ships and Silver, Taxes and Tribute: A Fiscal History of Archaic Athens. London & New York: Tauris.

Velde, F. R. 2013.

“On the Evolution of Specie: Coin Circulation and Weight Loss.” Revue numismatique 170: 605-650.

杂志排行

Journal of Ancient Civilizations的其它文章

- Index of Ancient Sources

- INCOME INEQUALITY, POLITICAL EQUALITY, AND TAXATION IN LATE-CLASSICAL ATHENS

- NARRATING CHECKS AND BALANCES? THE SETUP OF FINANCERELATED ADMINISTRATIVE DOCUMENTS AND INSTITUTIONS IN 5TH AND 4TH CENTURY BC ATHENS

- THE ATHENIAN COINAGE, FROM MINES TO MARKETS

- ABSTRACTS

- TAX MORALE IN CLASSICAL ATHENS