Old vs new:Risk factors predicting early onset colorectal cancer

2019-12-14AslamSyedPayalThakkarZacharyHorneHeithamAbdulBakiGursimranKochharKatieFarahShyamThakkar

Aslam R Syed,Payal Thakkar,Zachary D Horne,Heitham Abdul-Baki,Gursimran Kochhar,Katie Farah,Shyam Thakkar

Aslam R Syed,Heitham Abdul-Baki,Gursimran Kochhar,Katie Farah,Shyam Thakkar,Division of Gastroenterology,Allegheny Health Network,Pittsburgh,PA 15212,United States

Payal Thakkar,Allegheny Singer Research Institute,Allegheny Health Network,Pittsburgh,PA 15212,United States

Zachary D Horne,Division of Radiation Oncology,Allegheny Health Network Cancer Institute,Pittsburgh,PA 15212,United States

Abstract

Key words: Colorectal cancer; Early-onset colorectal cancer; Colorectal cancer screening;Epidemiology analysis; Colorectal neoplasm; Average-risk screening

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most common cancer and second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States and Europe.It continues to be a notable source of significant morbidity and mortality worldwide[1].The American Cancer Society (ACS) estimates there will be over 97000 new cases of colon cancer,over 43000 new cases of rectal cancer,and 50630 CRC-related deaths in 2018 in the Unites States alone[2].The overall lifetime risk of developing CRC is approximately 4.49% in men,and 4.15% in women.Fortunately,the incidence of CRC in all adults (age ≥ 50 years)has been decreasing as are the rates of hospitalizations[3].This is likely secondary to an increase in screening colonoscopies and removal of precancerous polyps[4].The average-risk screening is recommended to begin at 50 years of age in both males and females but can be earlier in individuals at a higher risk or whom have a positive family history of CRC.Recently,the ACS has released updated guidelines recommending average-risk CRC screening to be lowered to age 45[5].When considering those under 50,CRC has ranged from 7%-18% of all CRC patients[4,6].The national 2005-2009 surveillance,epidemiology,and end results data revealed the incidence was about 1.1% in those 20-34 years of age,4% in those 35-44 years of age,and 13.4% in those aged from 45-54 years of age[7].The incidence has also been reported as high as 28 per 100000 cases between ages 45-49 years[8].CRC mortality trends have also been on the rise in those younger than 50 years.Age-adjusted earlyonset CRC mortality rates from 2005-2009 ranged from 0.2-7.7 per 100000 population varying by age of CRC diagnosis,an overall increase of 2% annually from 1975-2004[9].In contrast,mortality rates for later-onset CRC has decreased by 2%-3% annually between 1992 and 2009[10].Many studies have proposed potential factors that may be associated with the rise of early-onset CRC.It has been implied that sporadic CRC accounts for the majority of early-onset cases[4].There also has been much discrepancy within literature observing hereditary factors as a minor or major attributing factor[11,12].Epidemiologic studies have proposed the rise is likely secondary to an increase of obesity,sedentary lifestyle,and diabetes mellitus[13-15].Other studies attribute the rise to hereditary syndromes,DNA mismatch repair,as well as other genetic syndromes[12].Pre-screening tools have even been proposed to evaluate whether or not patients should undergo tissue molecular screening to assess for these changes[16].

Retrospective studies have been conducted to risk-stratify early-onset CRC.Patients presenting with signs and symptoms of rectal bleeding,abdominal pain,change in bowel habits,weight loss,bowel obstruction and anemia have been associated with early-onset CRC[4].

However,no comparison studies have been conducted evaluating the differences in potential risk factors for various CRC cohorts.We aim to identify potential risk factors for early-onset CRC and compare these factors to a cohort of later-onset CRC (≥ 50 years) as well as control cohort defined as individuals 25-49 years old without diagnosis of CRC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Database

This population-based study was done using Explorys,a cloud-based platform,originally designed by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation (Cleveland,Ohio) in 1990,which was later acquired by IBM (Armonk,New York).This platform is a HITECH and HIPAA-compliant,national database search engine with the capacity to survey electronic medical records (EMR).One of the major advantages of Explorys is its capacity to survey millions of patients in minimal time.It provides aggregated data from claims data and EMRs such as Epic,Eclipsys,Amalga McKesson,and Cerner.Explorys is programmed to perform searches based on demographics,medications,and laboratory results,alone or in combination using the Systemized Nomenclature of Medicine-Clinical Terms.It can also apply a temporal relationship to various diagnostic testing and diseases (i.e.,establishing a symptom such as abdominal pain or rectal pain,prior to diagnosis of colorectal cancer).This study was approved by the Allegheny Singer Research Institute (Pittsburgh,Pennsylvania,United States) ethical review board on November 17,2017.It was exempt from a full institutional review as no identifying patient factors were observed or reported.This study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1976 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in by the Allegheny’s human research committee.

Patient selection

Explorys was used to perform a survey of all patients with an active EMR from January 2012 to December 2016.Search terms for the survey included a diagnosis of colon cancer and rectal cancer as a first-time incidence defined by the first diagnosis code entered.Once identified,we obtained 20 points of data from the records:age,gender,ethnicity (Caucasian,African American,Asian),body mass index,family history of cancer,family history of gastrointestinal malignancy,family history of colonic polyps,comorbidities of colitis,hyperlipidemia,hypertension,symptoms of abdominal pain,rectal pain,altered bowel function,rectal bleeding,weight loss,personal history of polyps,and tobacco or alcohol use.These criteria were selected based on prior reports of potential risk factors for early-onset CRC,as well as common demographic variables and comorbidities present in the elderly[4].

All CRC patients 25 years of age or older were included and stratified based on age(25-49 yearsvs≥ 50 years of age).Patients under 25 were excluded,as data on temporal symptomatology was not available in this cohort through the database.Demographics,comorbidities,and symptom profiles were recorded and compared between both age groups.Furthermore,the early-onset CRC cohort was also compared with a control group consisting of individuals aged 25-49 years without a diagnosis of CRC.

Potential risk factors for CRC were temporally evaluated.Search criteria ensured all family history of cancer,gastrointestinal cancer,and polyps,as well as symptom profiles (abdominal pain,rectal pain,rectal bleeding,weight loss and altered bowel function) presented prior to a diagnosis of CRC.In addition,only patients with a firsttime incidence of CRC were included in this study.These search criteria ensured that symptomology was present prior to a diagnosis of CRC rather than patients with well-established CRC presenting with symptoms after diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

All data collected by the database was enumerated using Microsoft Excel 2010 by Microsoft Inc.Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages.Differences in patient characteristics between the subgroups were compared using odds ratio (OR) with 95%CI and Foster plots were created[17].Because of the large discrepancy in the epidemiological data,odds ratio was normalized by conversion to Cohen’s d coefficient for computation of effect sizes according to Hasselblad and Hedges where advalue of 0.2,0.5,and 0.8 represents a small,medium and large effect respectively[18].Any conversion resulting in less than 0.2 signifies a trivial effect.Since effect sizes (ES) estimate the magnitude of effect or association between variables and are resistant to sample size influence,we used ES instead of OR for the judgment about practical significance.TheP-value was calculated using the statistical computing languageRwhere < 0.001 was considered statistically significant to limit spurious conclusions secondary to oversampling.The Explorys database rounds all numerical data to the nearest 10 persons to preserve patient anonymity.

RESULTS

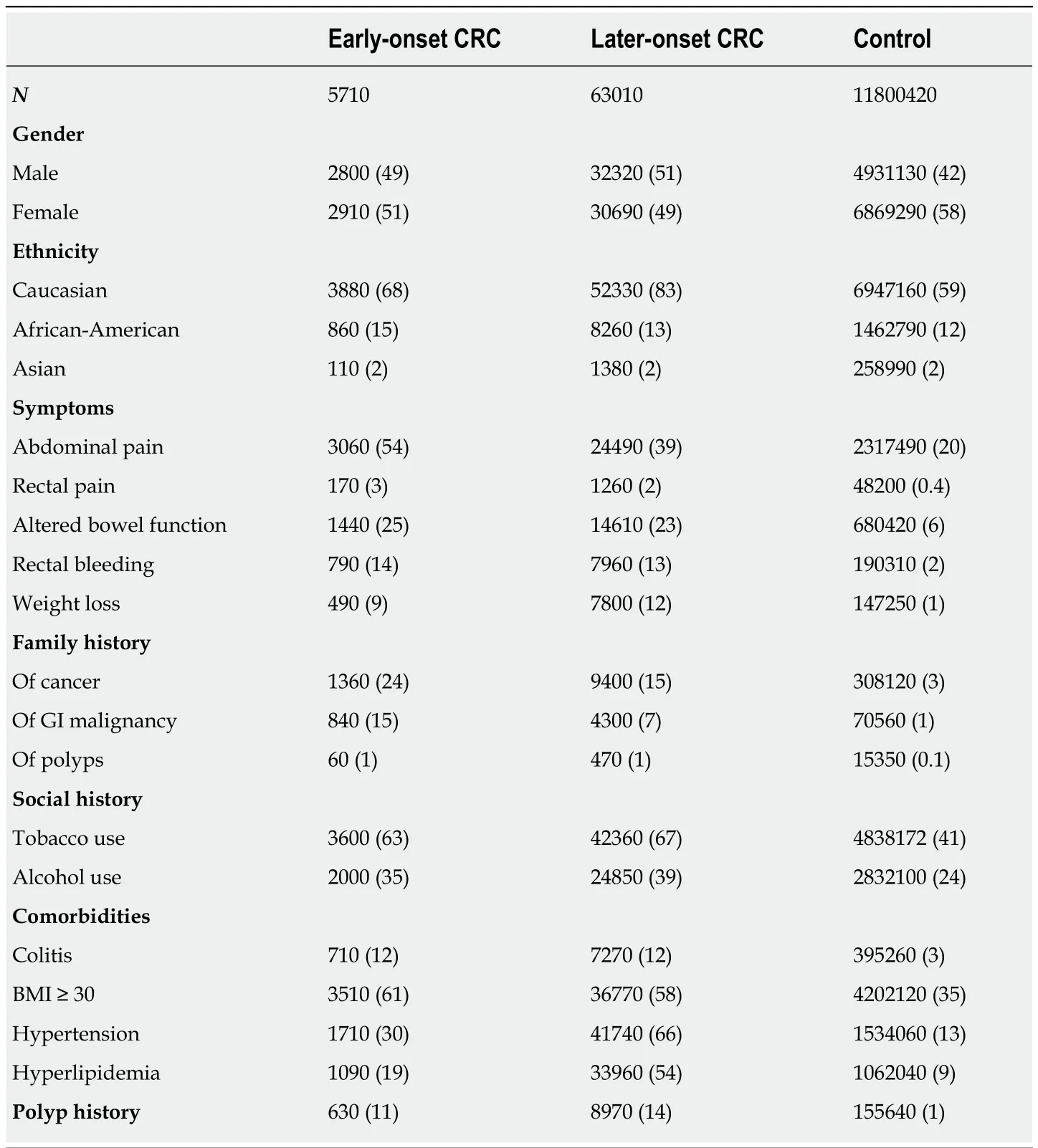

A total of 35493980 were identified in the Explorys database from 2012-2016.Of those,68860 patients (0.2%) were identified with CRC,of which 5710 (8.3%) were younger than 50 years old,with 4140 (73%) between 40-49 years of age (Table1).The remainder 140 patients were identified as 24 or younger and were excluded from the final analysis.A total of 11800420 patients were identified between ages 25-49 with no diagnosis of CRC,with even age distribution,42% being male,and majority being Caucasians (59%).A 20-point data set observation of all three cohorts is summarized in Table2.

Multivariable analysis demonstrated that several factors were associated with an increased risk of CRC in the early-onset CRC group versus the later-onset CRC group(P< 0.001).These factors included:African American race,presenting symptoms of abdominal pain,rectal pain,altered bowel function,having a family history of any cancer,gastrointestinal (GI) malignancy,polyps,and obesity (Figure1A).

Comparing the early-onset CRC cohort versus the control group,factors that were associated with an increased risk of CRC were:male gender,Caucasian and African-American race,presenting symptoms of abdominal pain,rectal pain,altered bowel function,rectal bleeding,weight loss,having a family history of cancer,GI malignancy,polyps,tobacco use,alcohol use,presence of colitis,obesity,hypertension,hyperlipidemia,and a personal history of polyps (Figure1B).

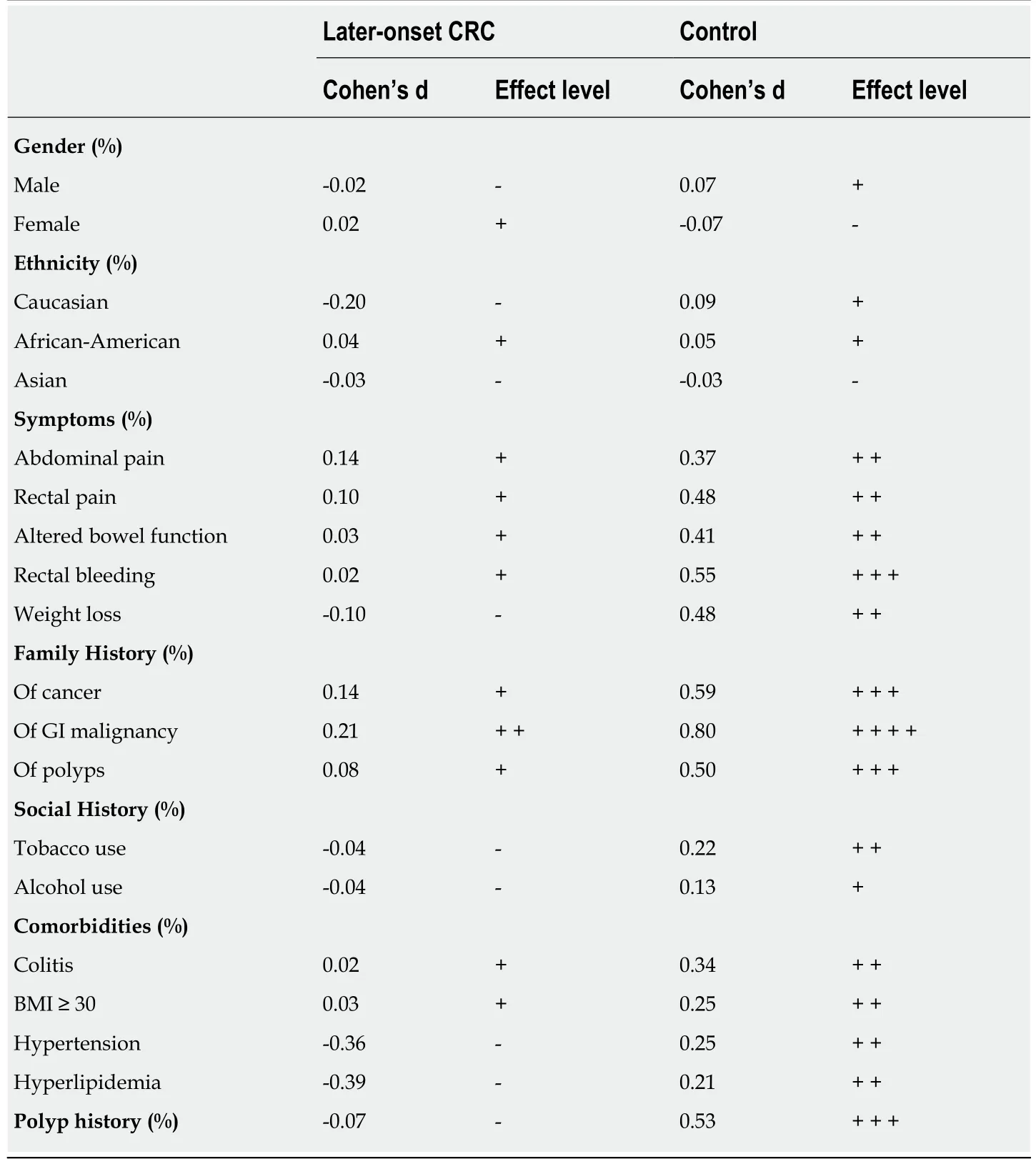

Conversion of odds ratio to Cohen’s d for standardized population difference to evaluate each factor impact on effect size is summarized in Table3.The only significant potential risk factor when comparing early-onset CRC to later-onset CRC was found to be having a family history of GI malignancy (d = 0.21).This was followed by having a family history of any malignancy (d = 0.14) and presenting symptoms of abdominal pain (d = 0.14),and rectal pain (d = 0.10).

The largest effect on a potential risk factor when comparing early-onset CRC to the control cohort was also having a family history of GI malignancy (d = 0.80),followed by having a family history of cancer (d = 0.59).Rectal bleeding (d = 0.55),having a history of a polyp (d = 0.53),family history of polyps (d = 0.50) all showed a medium effect.Other smaller effects were found to be symptoms of rectal pain (d = 0.48),weight loss (d = 0.48),altered bowel function (d = 0.41),abdominal pain (d = 0.37),colitis (d = 0.34),obesity (d = 0.25),hypertension (d = 0.25),tobacco use (d = 0.22) and hyperlipidemia (d = 0.21).

DISCUSSION

The rise of incidence,mortality,and hospitalizations of individuals with early-onset CRC remains concerning with previous studies reporting an incidence ranging from 7%-18%[4,6].Our data corroborates these findings as 8.3% of CRC patients in our study were younger than 50 years of age.Unfortunately,early-onset CRC typically presents in more advanced stages and is less resectable when compared to the elderly population[19].The majority of physicians’ attribute early-onset CRC to first-degree relative history,sporadic mutation,and genetic predisposition[4,12].However,physicians and the young population should be aware of many other potential risk factors to help identify populations for early screening.

Our analysis,which used a large nationally representative dataset,showed that early-onset CRCvslate-onset CRC is associated significantly with having a family history of any gastrointestinal malignancy.Other associated factors included:African American ethnicity,family history of cancer,family history of polyps,obesity,colitis,abdominal pain,rectal pain,rectal bleeding,and altered bowel function,which corroborates with prior reports[20-23].Current guidelines for initiating screening in African Americans recommend starting at age 45,which our study also supports[24].

Prior literature has not compared potential risk factors between early-onset CRC and a similar age-population excluding diagnosis of CRC.Associated risk factors are reported,and the largest effect was having a family history of a gastrointestinal malignancy.This was followed by the symptom onset of rectal bleeding,a personal polyp history,and having a family history of polyps.Other smaller effect observations included symptom onset of abdominal pain,rectal pain,altered bowel function,weight loss,tobacco use,colitis,obesity,hypertension and hyperlipidemia.

Population-based CRC screening for average-risk asymptomatic individuals starting at age 50 years is supported by the US Preventative Services and the Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research[25-26].Both young adults and physicians often fail to recognize symptoms for early-onset CRC,delaying the diagnosis.Symptomatic young patients often wait up to six months before seeking a medical professional[27].Once CRC symptoms arise,a thorough evaluation is needed to effectively establish or rule out early-onset CRC.Although a population-based database study may not justify a population screening approach,patient and physician awareness of several potential risk factors observed in our study should be taken into consideration.Clinicians overlook symptoms in young individuals and often attribute findings to alternative diagnoses[28].It is recommended that education efforts geared towards primary care physicians to pursue more aggressive work-up for young patients with symptomatology related to CRC may be warranted to develop an effective path to a more rapid diagnosis and treatment[27].

We recommend that young individuals identified with the risk factors outlined inthis study should undergo risk stratification for CRC screening.Risk factors with the largest effect include:Family history of gastrointestinal malignancy,family history of any malignancy,family or personal history of polyps,and rectal bleeding at the time of diagnosis.Comorbidities of colitis,obesity,a symptom presentation of abdominal pain,rectal pain,altered bowel function,and weight loss had a small-moderate association with early-onset CRC.These populations would most benefit from CRC screening for early diagnosis and potential prevention.In addition,young patients presenting with rectal bleeding should be appropriately managed and have CRC diagnosis ruled out.Cost-effectiveness studies are limited,but reports have demonstrated colonoscopy as an effective diagnostic strategy for individuals aged 25-45 with rectal bleeding[29].

Table2 20-point data set observation of the study cohorts,n (%)

There are a few limitations that should be acknowledged.The data has intrinsic limitations to an aggregated EMR database,where diagnoses rely on correct documentation in EMRs and does not correlate with clinical data.Also,potential risk factors were not corrected for all possible causes of early-onset CRC; this study proposed that having a family history of GI malignancy had a large effect for the development of early-onset CRC.This may suggest a genetic component for these individuals,which this database does not allow further elucidation.

As another limitation,a true regression analysis was not performed due to an aggregated de-identified data set,rather odd ratios were used.Additionally,potential associations with other comorbid conditions may create a bias toward one another.In order to limit this impact of confounding factors,aP-value of < 0.001 was set as the threshold of significant odds ratios,which were converted to Cohen’s d to standardize mean-difference for observation of effect of individual risk factors as recommended and accepted by multiple studies[18,30-31].Lastly,specific age ranges for patients with a family history of CRC were not observed.Therefore,patients with a family history of CRC should continue undergoing risk-appropriate CRC screenings with early initiation of colonoscopy.

Figure1 Odds ratio for early-onset colorectal cancer vs later-onset colorectal cancer and the control cohort.A:Early-onset colorectal cancer (CRC) vs lateronset CRC; B:Early-onset CRC vs the control cohort.GI:Gastrointestinal; BMI:Body mass index.

Prospective longitudinal analysis of patients with no predisposing hereditary or genetic factors with early-onset CRC should be observed and compared to a healthy cohort without diagnosis of CRC.It is important to note however,prospective studies associated with 20 points of data involving millions of patients would span many decades.A significant advantage of Explorys is the large cohort of patients that were surveyed in weeks by a small team of investigators.In addition,epidemiological trends as well as distinct comorbid conditions,age separation,and other factors are easily subdivided.

There have been many reports that identify potential factors attributing to the rise in incidence of early-onset CRC[6,28,32].However,the strength of our study is the comparison of early-onset CRC to average-risk CRC,as well as a control group without diagnosis of CRC within the same timeline.Routine CRC screening is not standard of care for patients under the age of 50; however,this study should help raise awareness of the rising incidence of early-onset CRC to help physicianspotentially screen individuals with associated risk factors relating to early-onset CRC development.

Table3 Effect level comparison for early-onset colorectal cancer

Identifying risk factors for early-onset CRC is necessary to optimize guidelines for early screening.A prospective clinical trial is the best way to address and understand potential risk factors for early-onset CRC.However,this would have an extensive cost and take many years to complete.This population-based study suggests clinicians should understand the importance of early-onset CRC,its increasing incidence,and potential risk factors to offer early screening.Pending further investigation,the risk factors outlined in this study should lower the threshold of suspicion for early CRC and potentially early CRC screening,especially in patients 40-49 years of age where incidence is highest.

In conclusion,young adults who have risk factors for development of early-onset CRC may need to be considered for earlier-onset screening protocols.These risk factors effect include:family history of gastrointestinal malignancy,family history of any malignancy,family or personal history of polyps,and rectal bleeding.Further studies in this population are necessary.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of all cancer related deaths in the United States.Unfortunately,incidence in the younger population is on the rise.Several studies have outlined the importance of screening,and potential risk-factors to help identify a higher than average-risk population.

Research motivation

Identifying potential risk factors in the younger population for colorectal cancer may effectively lower the incidence rate for early-onset CRC.Prior studies have reported risk-factors; however a comparison analysis between a young,healthy,cancer-free cohort and patients with early-onset CRC has not been reported.

Research objectives

This study mainly investigated the factors related to early-onset colorectal cancer incidence and compared them to a control cohort to help identify potential risk-factors.

Research methods

This population-based cohort analysis utilized a national database to determine potential riskfactors of early-onset colorectal cancer.Twenty factors were compared to a control population without prior or current diagnosis of early-onset CRC as well as a later-onset CRC group.Analysis was performed using odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals,followed by normalization by conversion to Cohen’s d coefficient.

Research results

Having a family history of gastrointestinal malignancy and/or any cancer resulted in the most significant risk of early-onset CRCvsthe control cohort and the later-onset CRC cohort.Identifiable symptoms found to be potential risk-factors included rectal bleeding,rectal pain,weight loss,abdominal pain,altered bowel function,colitis,obesity,hypertension,tobacco use,and hyperlipidemia.

Research conclusions

Young adults who have risk factors for development of early-onset CRC may need to be considered for earlier-onset screening protocols.These risk factors include having a family history of gastrointestinal malignancy,family history of any malignancy,family or personal history of polyps,and rectal bleeding.

Research perspectives

Clinicians should be aware of the rise of incidence of early-onset CRC.Vigilance to screen for CRC in this population should be based on potential risk-factors outlined in our study.Further prospective,long-term studies are necessary to elucidate the rising incidence of early-onset CRC.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology的其它文章

- Efficacy of hybrid minimally invasive esophagectomy vs open esophagectomy for esophageal cancer:A meta-analysis

- Clinical significance of MLH1/MSH2 for stage ll/lll sporadic colorectal cancer

- Endoscopic full-thickness resection for treating small tumors originating from the muscularis propria in the gastric fundus:An improvement in technique over 15 years

- Validation and head-to-head comparison of four models for predicting malignancy of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas:A study based on endoscopic ultrasound findings

- Revisiting oral fluoropyrimidine with cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer:Real-world data in Chinese population

- Oral chemotherapy for second-line treatment in patients with gemcitabine-refractory advanced pancreatic cancer