荷兰“绿心”—国家景观中基于适应气候变化的景观设计

2019-12-05荷兰瑞克菲索金石雨李卫芳

著:(荷兰)瑞克·德·菲索 译:金石雨 校:李卫芳

1 “绿心”(Green Heart)概况

1.1 圩田上的大都市

荷兰的兰斯塔德地区是由阿姆斯特丹、哈勒姆、莱顿、代尔夫特、海牙、鹿特丹和乌得勒支等历史名城形成的环形城市群落,占地面积约3 000 km2。超过800万人居住在这个经济中心,几乎是荷兰一半的人口。“绿心国家景观”(the Green Heart National Landscape,简称“绿心”)就位于这个环形城市群的中心。对这片泥炭地的改造始于中世纪早期。泥炭地经开采泥炭燃料,并作为农业用地进行去水处理,形成如今的圩田景观。现在,兰斯塔德遭受土地沉降和全球变暖导致的海平面逐渐上升的威胁(图1、2)。

1 北京和兰斯塔德的对比Comparison between Beijing and Randstad

2 “绿心”北部的历史变迁Historic development in the Green Heart (northern area)

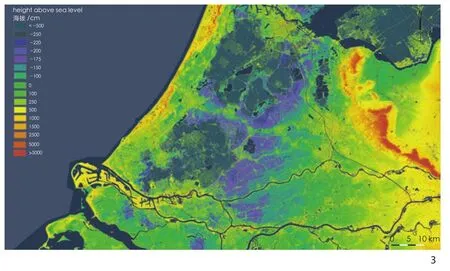

3 “绿心”和兰斯塔德地区的高程图:深蓝色部分代表之前由开采形成的泥炭沼泽区域,这些区域曾被洪水淹没,之后经围垦形成圩田,目前海拔介于-6 ~-4 m。紫色部分表示临近泥炭地有严重的土地沉降The height map of the Randstad Holland and the Green Heart:Dark blue parts represent the former peat bogs which were excavated.These excavated areas were flooded and later reclaimed and arranged as polders.They are currently situated 4 to 6 meters below sea level (NAP).The purple colour indicates strong soil subsidence in the adjacent peat areas

兰斯塔德和“绿心”的海拔目前几乎都处于荷兰海拔标准(Normal Amsterdams Peil,简称NAP)水位线0 m刻度之下,即低于平均海平面(图3)。曾经的泥炭沼泽经过人工挖掘后形成了湖泊,这些湖泊随后被排干,以开发新的农业区,其海拔介于-6 ~-4 m。荷兰的最低点为海拔-6.76 m,其位于鹿特丹东北Zuidplas圩田(于1841年进行围海造田)中的一片草地上。哈勒默梅尔(Haarlemmermeer)位于阿姆斯特丹附近,史基浦国家机场也坐落在此处,1852年,这里的泥炭地被抽干,平均海拔在-5 m。由于气候变化,这些在圩田上建造起来的大都市面临着巨大的压力。既要减轻海平面上升的影响,同时也要减少温室效应。此外,还面临着重大的空间挑战:必须使农业更具可持续性,停止进一步的土地沉降,增加生物多样性,并转向可再生能源的形式。而另一方面,还需要在2040年之前建造100万套住房。

1.2 气候变化

气候变化将对荷兰的空间规划产生重大影响,这一事实已毋庸置疑。《海平面的加速上升对三角洲计划的可能影响》[1]中展示了气候变化对沿海地基、用水安全和淡水供应的影响。在2050年之后,海平面有可能处于持续加速上升的状态。尽管现在还没有直接的科学证据,但越来越多的科学家指出,荷兰将会面临这种情况带来的问题,原因是南极洲的陆地冰盖融化得越来越快。海平面上升是否会加速以及加速的幅度都将取决于国际气候政策。

荷兰的政策旨在实现2015年巴黎举行的联合国气候变化大会上达成的目标—使全球升温控制在2℃及以下。但该目标是否可以在全球范围内实现尚无定数。依照荷兰现在的情形,到2100年海平面将上升0.35~1 m。鉴于海平面上升对荷兰的影响巨大,因此有必要考虑极端情况。若21世纪内全球温度升高4℃,到21世纪末海平面就可能上升3 m[1]。人们并不清楚哪些措施是最有效的,也不知道这些必然的变化进程是如何构建起来的。政府采取观望态度,好的政策不应仅局限于当下,还要考虑到未来。气候公园的出现是在呼吁政策制定者和发起者共同努力,建设可持续的、有价值的“绿心”国家景观。不仅要把气候变化视为威胁,更要把它视为机遇。

4 “绿心”气候公园剖面图①Sectional view of Climate Park①

2 “绿心”气候公园

2.1 两大挑战

荷兰西部面临两大挑战。1)适应气候变化和可持续水资源管理。“绿心”依赖于持续的排水和来自其他地方的淡水供应,这种依赖随着气候变化而加强,随之而来的还有安全和洪涝问题,这不是一个可持续的局面。我们还能继续增高堤坝多久,还能继续从地下抽水多久呢?而且,排涝耗费大量的能源和金钱。如果遇到干旱的夏季,就没有足够的水来满足巨大的需求。这就是为什么正在考虑采取严厉措施,例如将艾瑟尔湖(IJsselmeer)的水位提高超过1 m。不过,如果能将水蓄存在“绿心”,就不需要上述的措施了。气候公园的出发点是为“绿心”地区建立一个封闭的水平衡系统,不再依赖外部供水。2)提高生活质量,增强兰斯塔德的经济竞争力。在南部以及兰斯塔德的其他地区对高质量的乡村生活环境和方便可达的休闲场所有着巨大的社会需求,但是缺乏投资方面的行政决断力,而规划条例也会限制市场的主动性。因此,“绿心”气候公园的出发点是寻找经济功能和空间质量的新的结合点,实现“红—绿”区域的综合发展,而不是获得限制性的部门政策(图4)。

2.2 4个策略

气候公园具有四重景观策略(图5)。

2.2.1 水系

气候变化对兰斯塔德的安全构成严重威胁,进而也对整个荷兰的经济构成严重威胁。威胁来自2方面:海平面的上升和高地河道泄水。鹿特丹地区尤其脆弱,为了保证地区安全,需要对整个河流系统进行彻底的重新设计。由于城镇化和正在进行的基础设施建设都聚集在河流沿岸,要整合区域发展将是个艰巨的任务。“气候堤坝”(climate dike,超宽)的建设应该同打造宜人的、具有吸引力的河岸景观相结合。

沿着河岸,可以将城市改建、扩建与河道拓宽、堤坝加固工程结合在一起。兰斯塔德周围的14号环形堤坝可以被扩建为牢固的“气候堤坝”。这项设计不能仅是纯粹的文化—技术元素的组合,更应该是一个具有多种功能的景观结构。当在自然环境中建造新的建筑和特殊居住区时,也正是建设高质量城市河道及滨水景观的良好契机。集多功能于一体的河道滨水景观将对气候产生有益影响:空间的多用途、热电联产、高效的公共交通等优点。河道旁的建筑、历史悠久的沿河城镇、工业遗址、独特的河岸自然风光共同构成了“绿心”的主要景观结构,并在设计中得以强化。

2.2.2 重要的牧场草地景观

在农业领域,气候问题受到重视,比如贯彻实施水、营养、能量的封闭循环,减少CO2排放,增加农业生物多样性。规模化和集约化生产不符合上述要求,但是高品质生产是符合的。例如,有机乳制品产业比传统乳品业减少1/3温室气体的排放。河流黏土地区和有黏土底层的泥炭地也符合。在这些区域,保持农业文化景观和健康食品生产具有可持续的基础。

将区域特产贴上“绿心”质量标志,通过更好的市场营销合作,农业有可能迎来新的经济前景。很多公司发现了这一点并已经开始相互合作。“绿心”质量标志产生的经济效益还有可能进一步扩大,例如让“绿心”加入国际性的“慢城”(Cittaslow)运动中。意大利托斯卡纳地区是“慢城”运动的典型代表。该运动的中心思想是:采用传统的生产方式,热情好客,亲近自然界的土地、水、气候等。“慢城”还包括城市中可供人们休闲的路线和生态廊道,两者组成一个精细的网络。如果企业家们在纪念性建筑保护和历史景观恢复方面进行投资,他们将有很大的自由来开发新的服务和产品。

5 “绿心”气候公园概念The Climate Park concept

6 圩田上的伊杰堡②IJburg in the polder②

2.2.3 湿地基础设施

我们提议在比斯博什(Biesbosch)和艾瑟尔湖(IJsselmeer)之间建设一处湿地公园,打造自然湿地和休闲空间相结合的连续性区域。这样不仅形成了一个可靠的生态廊道,还能在结构上保护“绿心”中最脆弱的泥炭地,推动休闲旅游业的发展。湿地公园建设的核心是在最容易发生土地沉降的泥炭地区域采取截然不同的水管理措施(图3)。通过综合的方法,减轻对农业的影响,使宝贵的景观结构受到保护。

自动化造成农业用水水位不断下降,但这种现象正在被叫停,取而代之的是根据水位调整土地利用,这意味着该区域逐步向自然生态和休闲娱乐区域转变。水位可以根据自然条件上下波动,极大地增加了这一地区的蓄水能力。因此,该区域对外部水资源的需求会大幅减少,发生洪水的可能也少得多。这样一来,泥炭地就恢复了其“海绵”效应,地面甚至可以再次抬高,将这种地区称为“自然气候缓冲区”。景观会改变地区的风貌,但肯定不会降低其吸引力。生态方面,国际上对湿地的保护不断加强。湿地公园的建成将为大城市居民提供方便可达的自然休闲空间,也为水上运动、自然体验和发展文化旅游提供了新机遇。湿地公园内部的村落可以形成独特的乡村生活环境。在需要跨越基础设施的地方,会设置适合动物和人们通行的牢固的“景观桥”。只有通过综合的规划建设,才能为气候、景观和经济带来更多的附加价值。

2.2.4 荷兰湖区

被挖掘的泥炭沼泽可以说是“绿心”地区的“丑小鸭”,各种政策关注的都是泥炭草地景观区域。这一点可以理解:这块新围垦的土地有着一望无际的田野和笔直的道路,与那些古老的、富含水分的泥炭圩田相比,缺少休闲和生态方面的亮点。但这并不合理,因为这里是“绿心”发生盐碱化和干旱的源头,是洪水发生风险最大的地方。这里才最需要进行结构性设计,使其不受气候变化的影响。也正是在这里,人们可以从景观、自然、娱乐、生活和工作中受益良多。“绿心”公园接受了这些挑战,将展示“丑小鸭是如何变成白天鹅”的。

这片围垦地有多种多样的开发方式,无论是哪种,都会使区域水位大幅上升。在许多地方,为了自然的发展,会允许洪水浸没土地,从而给泥炭地恢复提供机会。事实上,水位逐渐升高能促进有机物质的积累,进而大量的CO2被捕获,地面再次抬升,这称之为“活的泥炭地”。

水产养殖业或沼泽种植业为圩田农业提供了新的选项。水产养殖是指养殖鱼、虾、贝类或水生植物。沼泽种植侧重于种植湿地作物,如香蒲、泥炭藓或浮萍,部分圩田可能因此被水淹没。湿地作物提供的是健康、环保、优质的食物,而且比从自然界直接获取、捕获食物的方式更加有益于环境。

“Terpen”是指“荷兰湖区”中的绿色生态居住岛,而“Terpen”的开发是最具深远意义、最具创新性的。为此,圩田必须全部或大部分被水浸没,水位最好高于海平面。形成的新水域为居民提供更多水上运动的机会,并形成湿地自然景观。岛上将设置较多的居住用地:海港村庄、绿色住宅区、滨水公寓、浮动码头住宅等。这些人工岛屿的建造必须使用大量的沙子,但不会超过伊杰堡(阿姆斯特丹)的用量。但是并非所有的圩田都适合。上述做法特别适合那些临近大城市、与道路和公共交通网络连接良好的圩田。“Terpen”可以满足兰斯塔德地区对乡村生活环境的高要求,通过真正可持续的水资源管理,能够创造出一个令人赞叹的新景观(图6)。

“绿心”气候公园不只是一纸蓝图,更是一种发展的观点,具有四重景观策略:1)水系:将城市功能集中到沿着河流的容纳能力较大、可达性较好的河岸上,并将滨水区域扩展到邻近的林缘开放景观;2)重要的牧场草地景观:通过在农业、自然管理和景观保护之间建立新的平衡,保护“开放式牧场景观”这一典型荷兰文化景观;3)湿地基础设施(泥炭景观和泥炭沼泽开采之间的过渡):通过调整水位管理、根据自然(泥炭地的再生)和休闲娱乐2个方面来改变区域功能,从而保护最脆弱的泥炭地区域;4)荷兰湖区:通过以可持续水管理、住房和旅游为重点的综合区域开发,解决深圩区严重的水问题。

7 生产型景观方案示意图Production scenario:Schematic map

8 生产型景观方案总体规划Production scenario:Masterplan

3 阿姆斯特尔兰(Amstelland)区域的实施策略

气候的不断变化和水资源管理成本日益增加,需要对如何应对土地沉降有一个新的认识。相关深入调查研究已经在靠近阿姆斯特丹的“绿心”中的阿姆斯特尔兰(占地4 500 hm2)展开,所有相关的问题都集中在一个小范围内。在与区域利益相关方和专家商讨后,制定了2种空间发展方案,并分别测试了它们对土地沉降、温室气体排放、水资源短缺、水资源过剩、生物多样性和景观的影响。

3.1 生产型景观方案

在这一方案中,解决土地沉降的方法是加速将乳牛业转化为自然循环农业。其核心在于:在泥炭区大规模应用水下排水系统,并在毗连的围垦地建设蓄水池。土地沉降和CO2排放量能够减半,开放式牧场草地景观(暂时)得到保护。蓄水池具有淡水供应和灌溉作物的双重功能,从而加强了农业生产结构。沿河的土壤因黏土、污泥和(或)城市堆肥的堆积而抬高,变成一个带有“城市花园”的休闲区(图7、8)。

3.1.1 对土地沉降的影响

各种研究表明,水下排水系统能减少近50%的土地沉降。这是因为在夏季,圩田的地下水保持在高位,因此进入土壤的氧气较少。压力排水似乎是最有效的。中央泵将水压进沟渠,将水通过输送管道送入排水管道中。这种措施可以进一步减少土地沉降到60%以上。

该方案的出发点:在夏季使用水下压力排水管道不会导致地下水位下降超过地面以下约30 cm。因为顶部30 cm仍然在氧化,土地沉降不会完全停止。到2100年Ronde Hoep地区的土地沉降不会达到1 m,而是40~50 cm。因此水位也会周期性下降,相应排水系统的位置也应有所改变。

草地鸟类保护区的土地沉降预计也是同样的规模。虽然这里没有使用压力排水,但是因为地下水位在冬、春季都达到地面高度,仅在夏季结束时达到最低点,土壤氧化的总时间就相对短。挖掘后的泥炭地将成为生态蓄水池,这些地方原则上会永久淹没,土地沉降将会完全停止。

3.1.2 对温室气体排放的影响

由于土地沉降减少,泥炭地的CO2排放量也将减少。假设500 hm2蓄水池的CO2排放量为零,那么剩余3 000 hm2泥炭地每年的CO2排放量约为2万t,总共能减少3.4万t的CO2排放。由于农业的广泛发展和奶牛数量、牛奶产量的减少(大约35%),预计每年还将减少约1万t的CO2排放。尽管CO2的总排放量减少了4.5万t,每年仍有3.9万t的CO2排放量,相当于9 000多hm2(阿姆斯特尔兰面积2倍)荷兰成熟林每年所吸附的CO2总量。

3.1.3 对供水需求的影响

压力排水设施可能会直接影响圩田的地下水位,且不受沟渠水位影响,因此沟渠(最高60 cm)中水位的波动幅度可以更大。这样,在不占用其他空间的情况下可以在圩田蓄存更多的水。岸堤的牢固性是一个需要关注的问题。如果沟渠水位低于最低水位,圩田蓄水池的水就会补充进来。蓄水池由雨水、渗水和圩田附近的剩余水补充。由于有来自渗透和排水系统的水,即使在干燥的夏季也会有水存留,同时需要防止蓄水池变干。据估计,在地表滞留区面积足够大的情况下,即使在干燥的夏季,泥炭地对供水的需求也可以减少到零。Bovenkerker圩田的外围区域面积约为400 hm2,蓄水400万m3,水位波动幅度为1 m。至于填海造地的其他地区,尤其是Bovenkerker圩田西部还需要外部供给冲厕用水,需要进一步调查是否可以使用蓄水池的水,或者是否有其他方法可以减少对外部供水的需求。

3.1.4 对排水系统的影响

沟渠和蓄水池水位可以波动,因此能应对大流量洪峰和防止boezem water③发生洪水泛滥。地表水用来收集和清除圩田水。一般来说,蓄水池中的水排到河流中,河流将水带到大海或艾瑟尔湖。通常情况下,水系统保持一定的蓄水能力是很重要的,也有利于水位管理。

3.1.5 对生物多样性的影响

在这个方案中,草地上栖息的鸟类拥有更多的生存机会,而与大自然相容的农业也将增添沟渠和河岸的自然生态价值。因为荷兰肩负保护草地鸟类特别是黑尾塍鹬(Limosa limosa)的国际责任,这是一个重要的加分项。湿地作物可能为水鸟和沼泽鸟类带来额外的益处,但很大程度上与作物的精准种植相关。

3.1.6 对景观的影响

此方案最大的优点是,开放的荷兰圩田景观将得到暂时的保留。牧场上仍然有奶牛漫步,虽然这些奶牛都是其他高产的荷斯坦奶牛,但更像是诸如blark head那样的“双用途奶牛”。但是这里也有重要的变化:蓄水池与湿地作物交织,形成了一种全新的景观。“城市花园”进一步强化了阿姆斯特尔河沿岸的绿色生态特色(图9、10)。

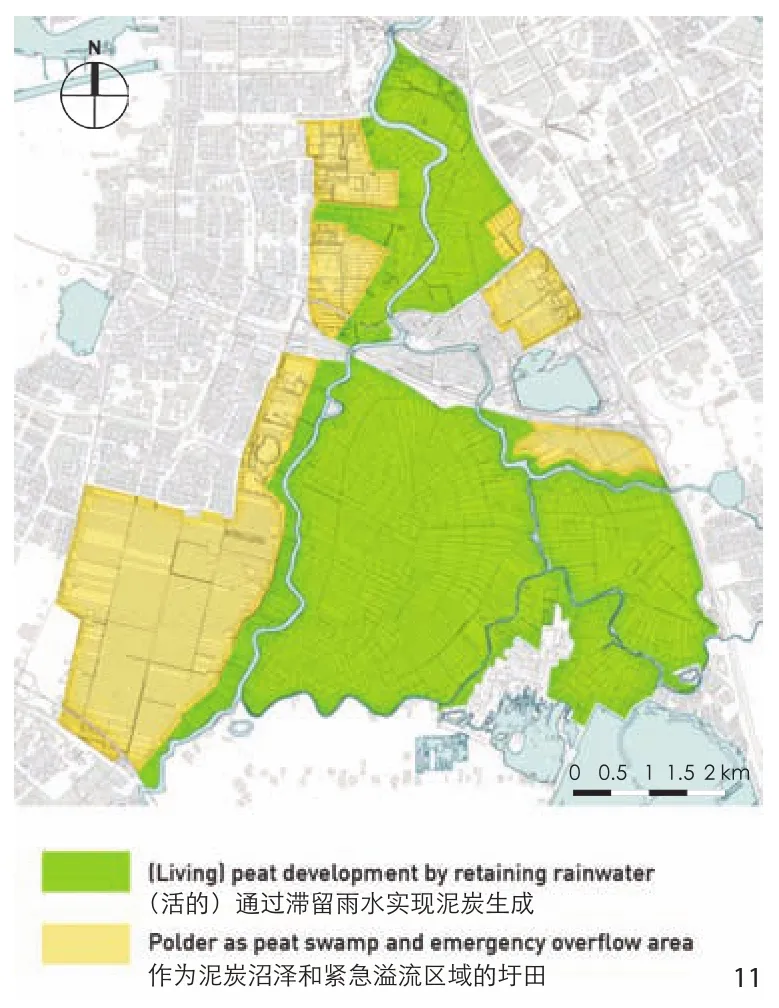

3.2 自然式景观方案

恢复泥炭地和最大限度保护生物多样性是这个方案的核心。收集并蓄存雨水,直到水位略高于地面。天然的泥炭沼泽将通过自然变化逐渐形成。泥炭藓是泥炭景观的自然组成部分,但由于挖掘和排水工程,泥炭藓几乎完全从“绿心”消失。泥炭层会捕获CO2,从而逆转土地沉降。此外,活的泥炭地就像海绵一样,可以存储大量的水分,这意味着水源短缺和大峰值泄洪都将成为过去。这样的整体转型需要大量的资金投入,也会产生很多的社会阻力。但另一方面,这样一个独特的“气候公园”的开发将有助于阿姆斯特丹都市圈的发展(图11、12)。

3.2.1 对土地沉降的影响

在这个方案中,土地沉降将完全停止并转化为地面抬升。在该地区的实地试验表明:在裸露的泥炭土壤上播撒泥炭藓,不到4年已经形成了8~12 cm的海绵状泥炭层。

3.2.2 对温室气体排放的影响

根据最近的研究来看,阿姆斯特尔兰泥炭地的恢复每年可以固定1.9万t CO2当量,减少7.3万t的CO2排放。此外,乳牛业的CO2排放将减少3万t,这样每年的总减排量相当于10.3万t CO2当量。每年释放1.9万t CO2当量相当于4 600 hm2森林(大约相当于阿姆斯特尔兰的面积)的吸附量。

3.2.3 对供水需求的影响

在这一方案中,对外部的供水需求将减到零。泥炭地最终达到完全依靠雨水(和圩田渗水)补给。泥炭地的海绵效应保证了土壤保持水分饱和,不会退化。

3.2.4 对排水系统的影响

有人担心有大量开放水域的地区会导致洪水泛滥,因为雨水不能存储到土壤中。这种想法假定了水位固定不变,水位一旦上升就会被排掉。但这个方案设定的情形不是这样的,在一定范围内,水位可以自然波动,这是我们希望的情况。这样就拥有了巨大的蓄水能力,有助于防止洪水发生。因为周边堤坝比较矮小和对水位管理的需要,泄洪峰值很容易突破,多余的水就要依靠泥炭地的海绵效应来吸收。如果在“绿心”大范围应用这种方法,那么建造单独的“紧急溢流区”的需求就会减少。不过这还有待进一步的调查。

3.2.5 对生物多样性的影响

在此方案中,草地鸟类将被迫和湿地其他物种分享空间,它们可能会出现在较低密度的湿地。无论如何,物种多样性都会大大增长。例如,稀有种类的蜻蜓和蝴蝶可以出现在贫瘠的泥炭沼泽。圩田富含养分的边缘区域和泥炭地为各种水鸟和沼泽鸟提供了栖息地。从国际角度来看,泥炭地十分有价值,特别具有荷兰三角洲的特色。

3.2.6 对景观的影响

有人担心在自然式景观方案中阿姆斯特尔兰会自动成长为森林,这种担心是不合理的。只要有正确的水资源战略和良好的过渡管理,开放式景观可以得到保留。从长期看,泥炭地几乎或根本不需要人工管理,因为这里的土地潮湿、贫瘠,不会生长树木。但景观特色一定会有所改变,沟渠将部分关闭,芦苇地和沼泽森林会出现,牧场上的牛会消失。关于这种情况是好是坏,人们有不同的观点。无论如何,这片充满生机的自然区域都为人们接近自然、休闲娱乐提供了新机会。而对于脆弱的草地鸟类栖息区,该方案精心设计了自行车道、步行道以及划船路线等游憩线路(图13、14)。

3.3 对比两个方案

两个方案对减少土地沉降和水资源管理方面的作用大不相同。在生产型景观方案中,土地沉降程度和温室气体排放可以减半;在自然式景观方案中,地面将抬高,大量的温室气体被捕获。这两种方案都需要巨大投资,都会重塑城市空间,对社会带来影响,需要进行更广泛的社会成本效益分析来作出更佳选择。目前,生产型景观得到的支持更多,也最有利于实现保护草地鸟类的目标。但也不能忽视,从长远来看,该区域将阶段性或部分地向自然式景观转换。自然式景观能为气候问题带来最大的效益(图15、16)。

4 结语

对“绿心”气候公园的研究和阿姆斯特尔兰地区的发展都表明,气候问题在未来景观设计中非常重要。在荷兰对于适应气候变化的紧迫性很突出。但“塞翁失马,焉知非福”,气候变化产生的挑战也为景观设计提供了许多新机遇:为了适应气候采取的必要措施可能带来更加可持续的农业区、新的自然区域、额外的游憩休闲空间、高品质的住宅区,达成人与自然双赢的局面。这些都需要综合的景观设计来实现[2-6]。

注释:

① 图4现状分析:剖面图显示处于低处的围垦地涌入很多地下水,有时甚至连更深层地表的咸水都涌进来。通过大型泵站,这些水被抽走,通过boezem排入海中。这种情况导致地表水的盐碱化和邻近泥炭地的干涸,从而限制了依赖淡水的农业区和自然区的发展。因此,需要从河流引入大量的水,以冲刷管道并保证泥炭地的湿润。然而这种水水质不佳,也不能无限度供给,因为河水流量会逐渐减少。在荷兰,理论上有足够的雨水,但是很快会被排放掉,因此在夏季有可能出现缺水的状况。此外的一个问题是,由于农业排水,泥炭地区域地面持续下沉。随着地面不断沉降,水位线也越来越低,水系统必须不断地调整,直到最后所有的泥炭都消失,而备受赞誉的泥炭景观也一同消失掉了!

图4未来图景:气候公园的本质是对“绿心”水系统做出一系列结构性的调整。最引人注目的是圩田的转变。水系统中的低洼位置必须得到解决。一种解决方法是将圩田完全置于水下,但这将意味着巨大的土地损失。另一种方法就是用沙子将一部分地块抬高,带来多种新用途。剩下的部分浸没在水中,提高“绿心”的蓄水能力。这样发生洪水和缺水的风险都大大降低,每年抽出和引入的水要少得多,因而节省了水资源管理成本。需要采取额外措施防止泥炭地的土地沉降,但通过进一步的升高或降低水位的措施是不行的。这样集约化精耕式农业就不可行了,新的机会留给了粗放式农业、自然(泥炭生长)和游憩休闲区域。沿河黏土土壤上的区域不易发生土地沉降,此处有充足的空间给集约化农业。

② 为了在阿姆斯特丹的伊杰堡建造大约18 000座房屋,总共用了2 500万m3的沙子在IJmeer建造岛屿。这是以IJmeer现有的开放水域和自然环境为代价的。莱茵河畔阿尔芬北部的Vierambacht圩田地势低洼,使用同样数量的沙子就可以将其打造成一个位于海平面以上的不破坏生态平衡的、可持续性的建设用地。通过将周围的土地淹没,可以同时实现蓄水、休闲、亲近自然等多种功能。伊杰堡位于“绿心”充满活力的西侧,前往兰斯塔德北部、南翼都十分便利,它的经济潜力显而易见。这3张关于Vierambacht圩田的伊杰堡地图可得出意外的结论是,“绿心”可以促进经济,同时还能一举解决水资源管理的可持续的调控问题。

③ 荷兰语单词boezem没有准确的翻译。boezem是一个水道和湖泊系统,作为圩田区水的中间储存库。圩田低洼处的水沉积在boezem上,可通过船闸或不通过泵送而排入外部水体。如果低洼区域的水位过低,可以从外部将水引入进来。在干旱时期,它用来让外部的水进入圩田,于是boezem具有一个明确的功能—淡水供应。boezem在圩田缺水的情况下发挥作用,为圩田提供河水,并确保在圩区水过多的情况下向大海或河流排放。

图片来源:

图2来自Pieter Veen,其余图片来自荷兰Vista景观与城市规划事务所。

(编辑/刘玉霞)

1 Introduction Green Heart

1.1 Polder Metropolis

The Randstad Holland covers an area of approximately 3,000 km2and consists of a ring of historic cities:Amsterdam,Haarlem,Leiden,Delft,The Hague,Rotterdam and Utrecht.More than 8,000,000 people live in this economic center,slightly less than half the population of the Netherlands.In the middle of this ring lies the Green Heart National Landscape.The reclamation of this peat landscape started in the early Middle Ages.The current polder landscape is the result of peat extraction (fuel)and dewatering by agriculture.Randstad Holland suffers from soil subsidence,whereas the sea level is gradually rising due to global warming (Fig.1,2).

Almost the entire Randstad and the Green Heart are now below the level of 0 meters NAP,the average sea level (Fig.3).Peat bogs were excavated,resulting in lakes,that were subsequently drained to develop new agricultural areas.These polders are on average 4 to 6 meters below NAP.The lowest point in the Netherlands is located at 6.76 meters below sea level in a meadow in the Zuidplaspolder (reclaimed in 1841),northeast of Rotterdam.Schiphol National Airport is located in Haarlemmermeerpolder near Amsterdam,which was drained in 1852 and is on average 5 meters below NAP.The polder metropolis in the Netherlands is under great pressure because of Climate Change.At the same time,we must both mitigate the effects of sea level rise and greatly reduce the greenhouse effect.In addition,there are major spatial challenges:we have to make agriculture more sustainable,stop further soil subsidence,increase biodiversity,and switch to forms of renewable energy.Moreover we need to build 1,000,000 homes by 2040.

1.2 Climate Change

The fact that climate change will have major consequences for the spatial planning of the Netherlands is hardly open for discussion anymore.The report ‘Possible consequences of accelerated sea level rise for the Delta Program[1],shows the impact on coastal foundations,water safety and freshwater supply.We may already be experiencing accelerated sea level rise after 2050.No scientific evidence has been provided for this,but more and more scientists indicate that this is a scenario that the Netherlands can be confronted with.The reason is that the land ice in Antarctica is melting faster and faster.Whether and how great the acceleration will be depends on international climate policy.

9 生产型景观效果图—Ronde Hoep圩田:目前农业的做法,如过度排水已经导致原有泥炭层严重的流失,从而给CO2排放和可持续水管理问题带来困难Ronde Hoep Polder:Current agricultural practices such as excessive drainage has led to a severe depletion of the preexisting peat layer,resulting in increasing issues regarding CO2 -emissions and sustainable water management

10 生产型景观效果图—Bovenkerker圩田:在生产型景观方案中,蓄水池将自然湿地和沼泽农业融合在一起Bovenkerkerpolder:In the production scenario,retention basins are created to accommodate natural wetlands and areas of wet agriculture (Paludiculture)

The policy in the Netherlands is aimed at achieving the climate goals of the United Nations Climate Change Conference of a maximum of 2°C worldwide temperature rise.But whether that will succeed worldwide is very uncertain.The current scenarios for the Netherlands assume a sea level rise between 0.35 meters and 1 meter up to 2100.Given the vulnerability of the Netherlands to sea level rise,it is therefore necessary to also take extreme scenarios into account.With a warming up to 4°C this century,a 3 meter scenario is possible before the end of this century[1].Which measures are most effective is yet unclear.Nobody knows how the necessary change processes are organized.Governments take a wait and see approach.Good policies are not limited to the present,but also extend to the future.The Climate Park is a call to policymakers and initiators to work together on a sustainable and valuable Green Heart.We should not only see climate change as a threat,but also as an opportunity!

2 Climate Park Green Heart

2.1 Two Major Challenges

Two major challenges facing West Netherlands are:

Climate adaptation and sustainable water management.The Green Heart is dependent on continuous drainage and supply of fresh water from elsewhere.This dependency increases with climate change.There is also the issue of safety and flooding.This is not a sustainable situation.How long can we continue raising the dikes? How long can we keep on pumping? The drainage of polders costs vast amounts of energy and money.In a dry summer there is not enough water available to meet the huge demand.That is why we are considering drastic measures such as water level increases of more than 1 meter in lake IJsselmeer.If we retain the water in the Green Heart,such measures may not be required.The point of departure for the Climate Park is that the aim is for a closed water balance for the Green Heart,thus independence from external water supply!

Improving the quality of life and strengthening the economic competitiveness of the Randstad.In the South Wing,but also in other parts of the Randstad,there is a great social need for high-quality rural living environments and easily accessible recreational areas.But there is a lack of administrative decisiveness to really invest in this.Planning regulations limit initiatives from the market.The starting point for the Green Heart Climate Park is to look for new combinations of economic functions and investments in spatial quality:so integrated red-green area development instead of restrictive sectoral policies (Fig.4)!

2.2 Four Strategies

The Climate Park had four landscape strategies(Fig.5).

2.2.1 River Systems

Climate change poses a serious threat to the security of the Randstad,and therefore to the economy of the entire Netherlands.The danger comes from two sides:sea level rise and higher river discharges.The Rotterdam Region is particularly vulnerable.A radical redesign of the entire river system is necessary to guarantee safety.Because urbanization and the ongoing infrastructure are concentrated along the rivers,this is an outstanding task for integrated area development.The construction of “climate dikes ”(extra wide) can be combined well with the formation of attractive river fronts.

Along the rivers we can combine urban restructuring and expansion with river widening and dyke reinforcement.The dike of dike ring 14 around the Randstad can be expanded into a robust “climate dike”.This should not be designed as a purely cultural-technical element,but as a multifunctional landscape structure.There are opportunities for high-quality urban river fronts,alongside new estates and special residential clusters in a green environment.Concentration of functions along the rivers yields a lot of climate benefits:multiple use of space,combined heat and power,efficient public transport.The rivers with the many estates,the historic river towns,the industrial heritage and the unique nature of the banks are reinforced as major landscape structures of the Green Heart.

2.2.2 Vital Meadow Landscape

In the agricultural area,climate issues play a role,such as the pursuit of closed cycles (water,nutrients,energy),a reduction in CO2emissions and an increase in agro-biodiversity.Scaling-up and intensification do not fit well with this,but a switch to quality production does.For example,organic dairy farming emits a third less greenhouse gas than conventional dairy farming.The river clay areas and the peat areas with a clay deck lend themselves well to this.In these areas there is a sustainable basis for maintaining the agricultural cultural landscape and healthy food production.

11 自然式景观方案示意图Nature landscape scenario:Schematic map

12 自然式景观方案总体规划Nature landscape scenario:Masterplan

With a Green Heart quality mark for regionspecific products and better cooperation in marketing and sales,a new economic perspective for agriculture is possible.Many companies have already discovered this and are already working together.This can be further expanded,for example by joining the international Cittaslow movement.The region Tuscany (Italy) is the model for this movement.Key ideas are:traditional production methods,hospitality and a conscious approach to the natural facts of soil,water and climate.Cittaslow includes also a fine-meshed network of recreational routes and ecological networks.Entrepreneurs are given a great deal of freedom to develop new services or products,provided that they simultaneously invest in the preservation of monumental buildings,the restoration of historic landscapes.

2.2.3 Wetland Infrastructure

The Wetland park is a proposal for the development of a continuous zone of water-rich nature and recreational areas between the Biesbosch and the IJsselmeer area.Not only does this form a robust ecological connecting zone,but it also offers a structural solution for the most vulnerable peat areas in the Green Heart and an economic boost for tourism-recreational development.The core of the development is a fundamentally different water management in those parts of the peat area that are most susceptible to soil subsidence (Fig.3).With an integrated approach,the consequences for agriculture can be mitigated and the valuable landscape structure preserved.

The automatism of ever-increasing water level reductions for agriculture is being stopped.Instead,the land use is adjusted to the water level.That means a gradual transformation into nature and recreational areas.Allowing natural fluctuations in water level greatly increases the water storage capacity.Much less water has to be supplied from elsewhere and there is less flooding.This way the peat regains its ‘sponge’ effect and the ground level can even rise again.We call this “natural climate buffers.” The landscape will change its image,but it will certainly not become less attractive.Ecologically there is a strengthening of the internationally protected wetlands.Accessible peat parks will be created for the residents of the major cities,with new opportunities for water sports,nature experience and cultural tourism.The villages in the Wetland park can develop into unique rural living environments.Where infrastructure is crossed,robust “landscape bridges” are created that are suitable for both animals and people.It is precisely through a combined development that much added value can be achieved for the climate,the landscape and the economy.

13 自然式景观效果图—Ronde Hoep圩田:自然景观促进“活的泥炭地”的再生,形成丰富的湿地沼泽景观Ronde Hoep Polder:In the nature landscape scenario,living peat is regenerated and forms a rich wetland bog landscape

14 自然式景观效果图—Bovenkerker圩田:自然式景观方案中开放水域繁茂的芦苇生机勃勃,沼泽森林也呈现到景观中Bovenkerkerpolder:In the nature landscape scenario,open water with reedlands are allowed to flourish,with areas of swamp forest also present in the landscape

2.2.4 Dutch Lake District

The excavated peat bogs are the ugly duckling of the Green Heart.All attention in policy goes to the peat meadow areas.Understandable:the relatively young reclaimed lands with their endless fields and straight roads are much less recreational and ecologically interesting than the age-old,water-rich peat polders.But that is unjustified,because this is where the cause of salinisation and desiccation lies in the Green Heart,and here the risks of flooding are greatest.It is precisely in the polders that structural measures are needed to achieve a climate-proof design.And it is precisely in the polders that a lot can be gained for landscape,nature,recreation,living and working.The Green Heart Climate Park takes up that challenge.It shows how the ugly duck can grow into a beautiful swan.

Various developments are conceivable for the reclamation sites,with the common denominator being a substantial increase in the water level.Inundation for nature development is already being put into practice here and there.This offers a special opportunity to regain peat formation.The fact is that a gradual increase in the water level can stimulate the accumulation of organic material.This way a lot of CO2is captured and ground level can rise again.We call this “living peat”.

Aquaculture or Paludiculture offers another interesting perspective for agriculture in the polder.Aquaculture is the breeding of fish,shrimp,shellfish or aquatic plants.Paludiculture focuses on wet crops such as cattail,peat moss or duckweed.Parts of land reclamation could be flooded for this.Wet crops ensure healthy,environmentally-friendly,high-quality food.Compared to harvest or catch from nature,there are many environmental benefits.

The most far-reaching and most innovative is the development of “terpen”:green residential islands in a “Dutch Lake District”.For this purpose,land reclamation sites must be submerged in whole or large parts,preferably above sea level.The new ponds offer an enormous expansion of water sports opportunities and water-bound nature.On the islands there is room for numerous residential environments:harbor villages,green residential areas,waterfront apartments or floating jetty houses.For the construction of the islands a lot of sand has to be applied,but no more than for example for IJburg (Amsterdam).Not all polders are suitable for this.Especially suitable are the polders that are close to the big cities and that are well connected to the road and public transport network.Terpen can substantially meet the high demand for rural living environments from the Randstad.At the same time,a fantastic new landscape can be created with truly sustainable water management (Fig.6).

The Climate Park was certainly not designed by us as a blueprint,but as a development perspective,with four landscape strategies:1) River Systems:concentration of urban functions on the highcapacity and well-accessible river banks along the rivers,in combination with the expansion of the river zones into forested edges of the adjacent open landscape; 2) Vital Meadow Landscape:preservation of the typical Dutch cultural landscape of the open pasture landscapes,by creating a new balance between agriculture,nature management and landscape conservation; 3) Wetland Infrastructure(transition between peat landscape and peat bog excavations):preservation of the most vulnerable peat areas,through adapted water level management and function changes in the direction of nature(regeneration of peat) and recreation; 4) Dutch Lake District:tackling the serious water problems of the deep polders,through integrated area development focused on sustainable water management,housing and tourism.

3 Regional Implementation Amstelland

Climate change and the increasing costs for water management require a new vision on how to deal with soil subsidence.This has been further investigated for Amstelland (4,500 hm2) in the Green Heart near Amsterdam.All relevant issues come together here on a small scale.Two spatial scenarios have been developed in consultation with regional stakeholders and experts and tested for their effects on soil subsidence,greenhouse gas emissions,water shortage,water surplus,biodiversity and landscape.

3.1 Scenario Production Landscape

In this scenario,the approach to soil subsidence is used for an accelerated transition from dairy farming to nature-inclusive circular agriculture.The core of this scenario is the largescale application of underwater drainage in the peat areas and the construction of retention basins in the adjoining land reclamation sites.Soil subsidence and CO2emissions are halved and the open pasture landscape is (for the time being) safeguarded.The retention basins are given a dual function for freshwater supply and for wet crops,thus strengthening the agricultural production structure.The soils along the river are raised with clay,sludge and/or urban compost and transformed into a recreational zone with “urban gardens” (Fig.7,8).

3.1.1 Effect on Soil Subsidence

Various studies have shown that underwater drains can reduce soil subsidence by approximately 50%.This is because the groundwater level in the plots is kept high in the summer and therefore less oxygen enters the soil.Pressure drains seem the most efficient.The ditch water is supplied by a central pump and the drains are pushed in via a distribution pipe.The reduction in soil subsidence can then rise to more than 60%.

In this scenario,the starting point is that the use of pressure drains in the summer does not cause the groundwater level to drop further than approx.30 cm below ground level.Because the top 30 cm is still oxidizing,the subsidence will not be completely stopped.In the Ronde Hoep,the fall to 2100 will not be 1 m,but 40 to 50 cm.The water level will therefore have to be lowered periodically,and that also applies to the location of the drains.

The land subsidence in the meadow bird sanctuary is expected to be in the same order of magnitude.Although no pressure drains are applied here,but because the water level reaches ground level in winter and spring,the groundwater will only reach its lowest level at the end of the summer and the total oxidation period will be shorter.The excavated peat bog areas are set up as retention basins and are in principle permanently submerged,the soil subsidence will be completely stopped.

3.1.2 Effect on Greenhouse Gas Emissions

As a result of the reduced subsidence,CO2emissions from peat areas will also decrease.Assuming zero emissions for the retention basins(500 hm2),we arrive at an annual emission of around 20,000 tonnes (tonne=metric ton=1,000 kg) of CO2equivalents for the remaining 3,000 hm2peat area,a reduction of 34,000 tonnes..As a result of the extensification of agriculture and the reduction in the number of cows and the quantity of milk produced (by around 35%),an additional reduction in CO2emissions is to be expected with around 10,000 tonnes of CO2annually.With a reduction of 45,000 tons of CO2,emissions of 39,000 tons of CO2per year remain.This corresponds to what a mature Dutch forest of more than 9,000 hectares in a year captures,still double the surface of the entire Amstelland.

3.1.3 Effect on Water Requirement

The installation of pressure drainage makes it possible to directly influence the groundwater level in the plots,more or less independent of the ditch level.Larger level fluctuations are therefore possible in the ditches (up to 60 cm).In this way,much additional water storage can be realised in the polder without taking up space.The stability of the banks is a point of attention.If the ditch level falls below the minimum level,water is replenished from the retention basin in the polder.The retention basin is fed by rainwater,seepage water and surplus water from the adjacent part of the polder.Due to the seepage and the drainage water,water remains present even in dry summers and the retention basin is prevented from becoming empty.It is estimated that with sufficient surface retention area,the intake requirement of the peat areas can also be reduced to 0 in dry summers.The indicated peripheral zone of the Bovenkerkerpolder is approximately 400 hm2; this results in 4 million m3of water storage with 1 m level fluctuation.For the other parts of the polder,in particular the western part of the Bovenkerker polder,inlet water will still be necessary for flushing.It must be investigated further whether this water can also come from the retention basin or whether other solutions are possible to reduce the flushing inlet.

3.1.4 Effect on Water Drainage

The level fluctuations in the ditches and in the retention basins also make it possible to cope with large discharge peaks and to prevent flooding on the ‘boezem water’.This is surface water that serves to collect and remove polder water.In general,the water from the basin is discharged into a river that brings the water to the sea or to the IJsselmeer.It is important that a certain reserve capacity remains in the water system in normal situations.This is easy to arrange with water level management.

3.1.5 Impact on Biodiversity

The meadow birds get extra opportunities in this scenario,and nature-inclusive agriculture will also increase the nature value of ditches and banks.Because the Netherlands has an international responsibility for the conservation of meadow birds,in particular the black-tailed godwit,this is an important plus.The wet crops may have an additional significance for water and marsh types,but that depends strongly on the precise cultivation.

3.1.6 Effect on Landscape Image

The biggest asset of this scenario is that the image of the open Dutch polder landscape will be maintained for the time being.Even with cows in the pasture,although these are other cows that are high-yielding Holstein dairy cows,but rather“double-purpose cows” such as the blark head.Nevertheless,there are also major changes:the retention basins with wet crops form a completely new type of landscape.The green character along the river Amstel is reinforced by the new “city gardens” (Fig.9,10).

15 现状、生产型景观方案和自然式景观方案对比示意图Contrast schematics of current situation,production scenario and nature landscape scenario

16 CO2排放的整体比较Overall comparison of CO2-emissions

3.2 Natural Landscape Scenario

Peat recovery and maximum biodiversity are central to this scenario.We save rainwater until the water level reaches a little above the land.Natural moor peat will gradually be created through natural changes.Peat moss development is naturally part of the peat landscape,but has almost completely disappeared from the Green Heart due to excavation and drainage.Peat formation captures CO2and will reverse soil subsidence.Moreover,living peat works like a sponge,it retains a lot of water,which means that both water shortages and large peak discharges will be a thing of the past.Such an integral transformation requires huge investments and will generate a lot of social resistance.On the other hand,a unique “climate park” can be developed that contributes to Amsterdam Metropolitan Area(Fig.11,12).

3.2.1 Effect on Soil Subsidence

In this scenario,the soil subsidence is completely stopped and converted into soil rise.Practical tests in the area showed that a sponge-like peat layer of 8 to 12 cm had already formed within 4 years after seeding of peat moss on bare peat soil.

3.2.2 Effect on Greenhouse Gas Emissions

On the basis of recent studies,recovery of peat soils in Amstelland will fix 19,000 tonnes of CO2equivalents annually,a decrease of 73,000 tonnes.In addition,CO2emissions from dairy farming will decrease by 30,000 tonnes.The total reduction in emissions therefore amounts to 103,000 tonnes of CO2equivalents annually.The annual emissions of 19,000 tonnes of CO2equivalents corresponds to that of 4,600 hm2of forest,approximately the same area as Amstelland.

3.2.3 Effect on Water Requirement

In this scenario,the external water requirement is reduced to 0.The peat areas are after all fully fed by rainwater (and seepage in the polder).The sponge effect of the peat ensures that the soil remains water-saturated and does not degrade.

3.2.4 Effect on Water Drainage

There is a fear that areas with a lot of open water will quickly cause flooding,because rainwater cannot be stored in the soil.However,this assumes that the water is kept at a fixed level and that every cm level rise is immediately drained.This is not the case in this scenario.Natural level fluctuations are possible and desirable,within certain limits.This provides a large storage capacity and helps to prevent flooding.Due to small dikes at the edges and water level management,drain peaks can easily be capped.The sponge effect of the peat does the rest.If this is applied on a larger scale in the Green Heart,the need to construct separate “emergency overflow areas”diminishes.This still requires further investigation.

3.2.5 Impact on Biodiversity

The meadow birds will have to share their place in this scenario with other species of wetlands,and probably occur in lower densities.In any case,the diversity of species will increase enormously.For example,rare dragonfly and butterfly species can occur in the most nutrient-poor peat bogs.The nutrient-rich edges and the peat bogs in the polder form a habitat for all kinds of water and marsh birds.From an international perspective,peat bogs are particularly valuable and originally very characteristic of the Dutch delta.

3.2.6 Effect on Landscape Image

The fear that Amstelland will automatically grow into forest in the nature scenario is unjustified.Openness can be preserved with the right water strategy and good transition management.In the longer term,hardly any or no management is required in the peat bogs:due to the wet and nutrient-poor conditions,they naturally remain tree-free.The character of the landscape will certainly change.The ditches will partially close,reedlands and swamp forests can arise locally.There will be no more cows in the pasture.Opinions differ as to whether that is bad.In any case,the contiguous “robust” nature areas in this scenario offer new opportunities for nature experience and recreation.In contrast to vulnerable meadow bird areas,finer-meshed recreational access with cycling and walking paths and canoe routes is possible (Fig.13,14).

3.3 Comparison scenarios

Both scenarios differ substantially in their contribution to reducing soil subsidence and water management.In the production landscape the soil subsidence and associated emissions can be halved,in the natural landscape the soil will rise and greenhouse gasses will be actively captured.Both scenarios require substantial investments and have major spatial and social consequences.To arrive at a well-considered choice,a broader social cost-benefit analysis is needed.At the moment,the production scenario appears to have the most support and to best fit in with the meadow bird objective.But it cannot be excluded that in the long term the (phased or partial) transition to a natural landscape will nevertheless be addressed.The natural landscape provides the most climate benefits (Fig.15,16).

4 Finally

The Green Heart Climate Park studies and the Amstelland Regional Development show that the climate challenge is important for the design of the future landscape.The urgency for climate adaptation is high in the Netherlands.But sometimes that seems like a blessing in disguise.The studies show that climate adaptation also offers a lot of new opportunities for the design of the landscape.Necessary measures lead to more sustainably furnished agricultural areas,new nature areas,extra space for recreation and tourism and to exciting and high-quality residential areas.Actually all win-win situations.This requires an integrated approach from landscape architecture[2-6].

Notes:

① Current situation of Fig.4 :The cross-section shows that the low-lying reclamation sites attract a lot of groundwater.Sometimes even salt water comes up from the deeper surface.With large pumping stations,this water is pumped away and drained to the sea via the ‘Boezem’¹.This situation leads to the salinization of the surface water and to the drying out of the adjacent peat areas.This limits the possibilities for agriculture and nature,because they depend on fresh water.That is why a lot of water is let in from the rivers,for flushing the drains and maintaining the peat areas.However,this water is of lesser quality and does not have an unlimited supply because the rivers will discharge less water.In principle there is enough rain in the Netherlands,but all the water is discharged quickly,therefore shortages still occur in the summer.An additional problem is the continuing subsidence in the peat areas,as a result of agricultural drainage.In order to follow this subsidence,the level is lowered again and again and the water system must be continuously adjusted until finally all the peat has disappeared.And with it the muchappreciated peat landscape!

Future situation of Fig.4:The essence of the Climate Park is a number of structural interventions in the water system of the Green Heart.The most striking thing is the transformation of the polder.These lower situated parts in the water system must be solved.Putting the polder under water is a solution,but that would mean a huge loss of land.An alternative is to raise parts with sand,creating all kinds of new uses.Other parts can be submerged which will provide an increase in the water storage capacity in the Green Heart.The risk of flooding and water shortage is thus much reduced.Much less water has to be pumped out and let in every year.This results in savings in the costs of water management! Extra measures are needed to prevent subsidence of the peat areas.This is possible by not further lowering the water level,or actively raising it.Intensive agriculture is then no longer possible,but new opportunities arise for extensive agriculture,nature (peat development) and recreation.Sufficient space remains for the intensive agriculture on the clay soils along the rivers,which are less sensitive to subsidence.

② For the construction of approximately 18,000 homes in IJburg Amsterdam,a total of 25 million m3of sand was used to build islands in the IJmeer.This is at the expense of existing open water and existing nature in the IJmeer.A sustainable building site above NAP could also be realized with the same amount of sand in a low-lying polder Vierambacht,north of Alphen a/d Rijn.By inundating the surrounding land,a substantial contribution can be made at the same time to water storage and the development of new recreational and nature areas.Located in the dynamic western flank of the Groene Hart and easily accessible from both the north wing and the south wing of the Randstad,the economic potential of the location is evident.The surprising conclusion of this map montage of the IJburg map in Polder Vierambacht is that a powerful boost can be given to the interpretation of the Groene Hart and that water management can be sustainably regulated in one fell swoop.

③ Unfortunately there is no translation of the Dutch word‘boezem’.A ‘boezem’ is a system of watercourses and lakes that serve as intermediate storage of the polder water.The water from lower-lying polders is deposited on the boezem and can be discharged into the external water through locks with or without pumping.If the water in the basin is too low,water can be brought into the basin from the external water.During dry periods,this is used to let extra water into the polder; in this way the ‘boezem’ has a clear function with regards to the freshwater supply.

The boezem functions in polders in the event of water shortage,for the supply of water from the rivers to polders,and also ensures the discharge of water to the sea or rivers in the event of water surplus.

Sources of Figures:

Fig.2 ©Pieter Veen,other figures©Vista Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning.