三角洲适应性转型

——基于景观的区域设计方法

2019-12-02斯特芬奈豪斯熊亮丹尼艾勒坎纳特拉

(荷)斯特芬·奈豪斯 熊亮 (意)丹尼艾勒·坎纳特拉

处于城市化进程中的三角洲地区是世界上最富希望且动态十足的区域之一。其在世界生态系统和全球经济中的地位举足轻重[1]293,[2],为水系统主导的多种敏感性环境中的种群聚集提供了条件。同时,由于集约型城市土地利用和经济活动在敏感性水环境中难以维持,这些三角洲极其脆弱,面临多重威胁[3-4]。如果缺乏有效的管治就尝试维持这些活动,将造成生态系统的破坏和社会—文化价值的损失,也将削弱三角洲抵御自然灾害和气候变化的能力。其结果将影响三角洲地区的环境、经济以及生活在这些水系统中居民的健康和繁荣[5]2-3。

城市化三角洲可视为一系列复杂社会—生态系统的集合。这些系统包含的各子系统具有独立的动态特征和速率变化(图1)。空间战略可以保障这类区域的可持续发展,增强其韧性、协助各系统修复漏洞,并增强这些系统应对自然和人工威胁的能力。这些空间战略应能协调各系统间的关系,减少破坏性的系统间矛盾,例如城市发展引起的洪涝风险增加。生态敏感型的城市开发具有保障经济社会增长的潜力,而空间战略应关注这方面的潜力,并为增强自然系统和水安全提供契机[5]3-4。同时,其也应包含广泛的社会和经济参与者,以支撑当地的社会、经济和文化。有说服力的沟通方式能使这类空间战略得到广泛的理解和支持,并产生影响[6-7]。

除了改善三角洲地区的生存条件之外,空间战略还能通过应对气候变化来降低气候相关的风险等级。为创造更有韧性的三角洲区域,城市规划和管理需要有一定的适应能力。空间战略应该识别出生态动力设计的可能。在这些设计中,自然与城市的发展有机会得到整合,确保水安全的适应性设计导则也能得以实现。此外,对空间规划、设计和灾害管理中的各种转型性过程的整合也十分必要。由此可以改善土地利用、机构间协调和机制间关系,促成有效、可持续和全纳的城市发展[5]6。

1 广州市琶洲典型的渔村与新城开发反映了长短期发展之间的矛盾Confrontations between incremental long-term and fast short-term developments indicated by fisherman villages and new urban development in Pazhou, Guangzhou

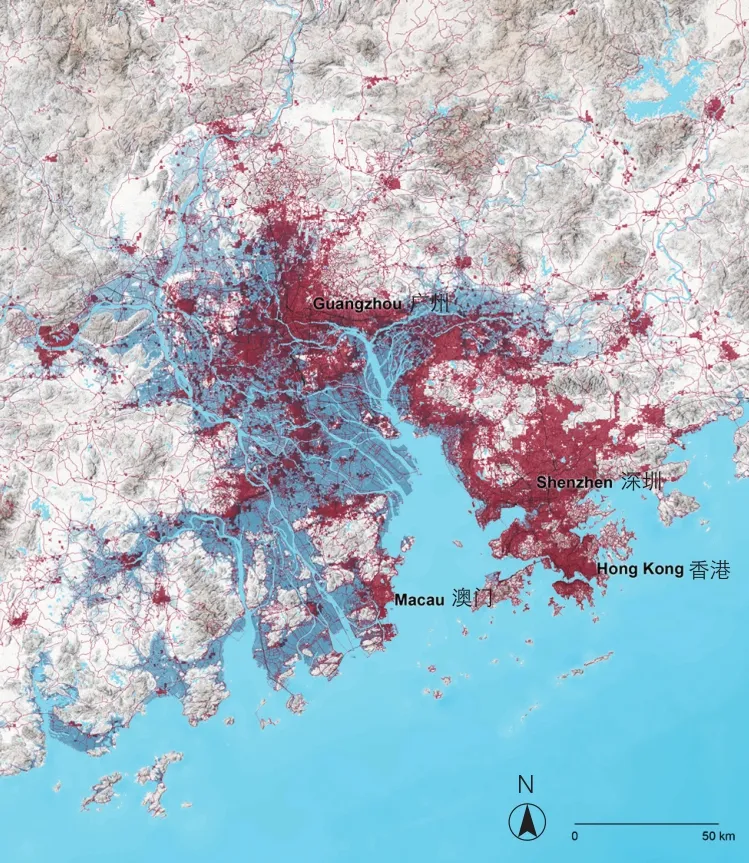

2 大部分城市化区域位于洪涝易泛的低地(+10 m地区,深蓝部分),增加了洪涝风险Most of the urbanization takes place in the flood prone lowland (+10 m zone, indicated in dark blue), which increases the flood risk in PRD

自21世纪以来,在城市化三角洲地区规划设计领域出现了一系列旨在发展适应性系统的研究。包括荷兰的莱茵—马斯—斯海尔德河三角洲[8-9],美国的密西西比河三角洲[10-11]以及越南的湄公河三角洲[12-13]。研究表明,与传统规划战略相比,在国土治理中采用城市景观动态的视角能获得更大的潜在收益[1]293-312,[14-15]。本文阐明了在城市化三角洲中,通过基于景观的区域设计实现适应性城市转型的方法。对珠江三角洲进行案例分析的同时,也着重阐述这一城市景观规划设计一体化方法。该方法强调城市景观的规划和设计须根据适应性城市转型的要求,对自然和城市动态的适应性节奏和性质进行调节[5]6。

适应性城市转型采用了基于景观的区域设计方法,将其作为整合性、多尺度的规划设计途径。如此可以结合多部门活动,促进城市和乡村多种转型性过程的发展,以取得更协调的可持续性成果。基于景观的区域设计是塑造区域形态的重要战略,其以景观为基础产生可持续的城市化三角洲,也通过空间规划和设计为长期可持续的城市景观发展提供途径。一言以蔽之,区域设计是一种跨学科的尝试,不但保障可持续和连续性发展,也指导和塑造由社会—经济和环境过程引起的改变,同时通过有形的关系为区域建立当地特色[16]43-46。

1 珠江三角洲

在过去40年间,珠江三角洲(简称珠三角)是世界上发展最快速的三角洲地区。2014年,其超越东京湾地区,成为世界上面积最大、人口最多的城市区域[17]。20世纪80年代起,珠三角一直处于中国城市化和社会经济转型改革的前沿阵地[18]。然而,由于气候变化和环境恶化,珠三角的远期经济发展需要应对巨大挑战,包括红树林生态系统消失[19]、农田流失[20]、空气和水污染[21]、水资源短缺[22]、社会治安问题[23]等。

一方面,由于洪涝易泛区的城市化(图2),使珠三角暴露在持续增长的洪水风险之中。海平面的持续上升、夏季台风等极端性热带风暴的加剧对区域内的基础设施持续施压。另一方面,珠三角的生态系统日趋破碎和脆弱[24],表现为生态系统服务[25]和环境承载力[26]的降低。宏观尺度的干预使千篇一律的单一性空间在微观尺度上取代了多样的历史性环境和文化遗产[27]。虽然有关部门积极推进一体化规划设计方法,但仍未进行大范围的有效施行[28]。例如“海绵城市”的建设难点之一就是整合不同部门之间的多种规划[29]。

为了珠三角的可持续发展,急需在其城市发展中采用新的规划设计方法。针对经济发展和环境修复之间的矛盾,以及气候变化带来的相关风险,区域设计提供了一种解决之道,即发展基于景观的概念和实践。珠三角的高速发展使其成为一个尤有价值的案例,在此案例中可以探索和验证这些更具适应性的整体规划方法的潜力,而基于景观的区域设计就是这类整体规划方法中的一种。

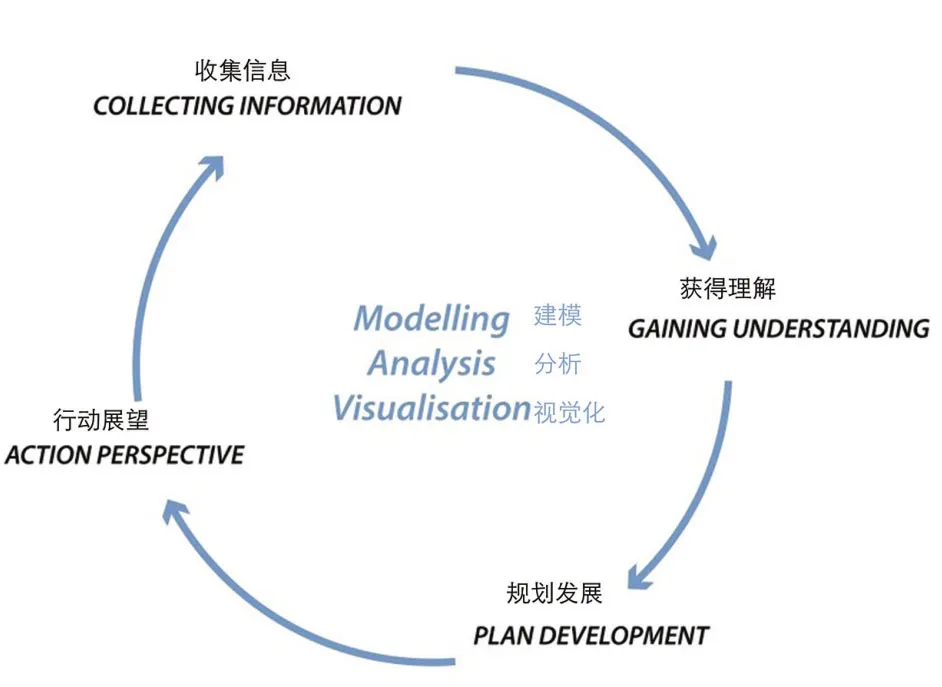

3 基于景观的区域设计的4个重要阶段Four important phases in landscape-based regional design

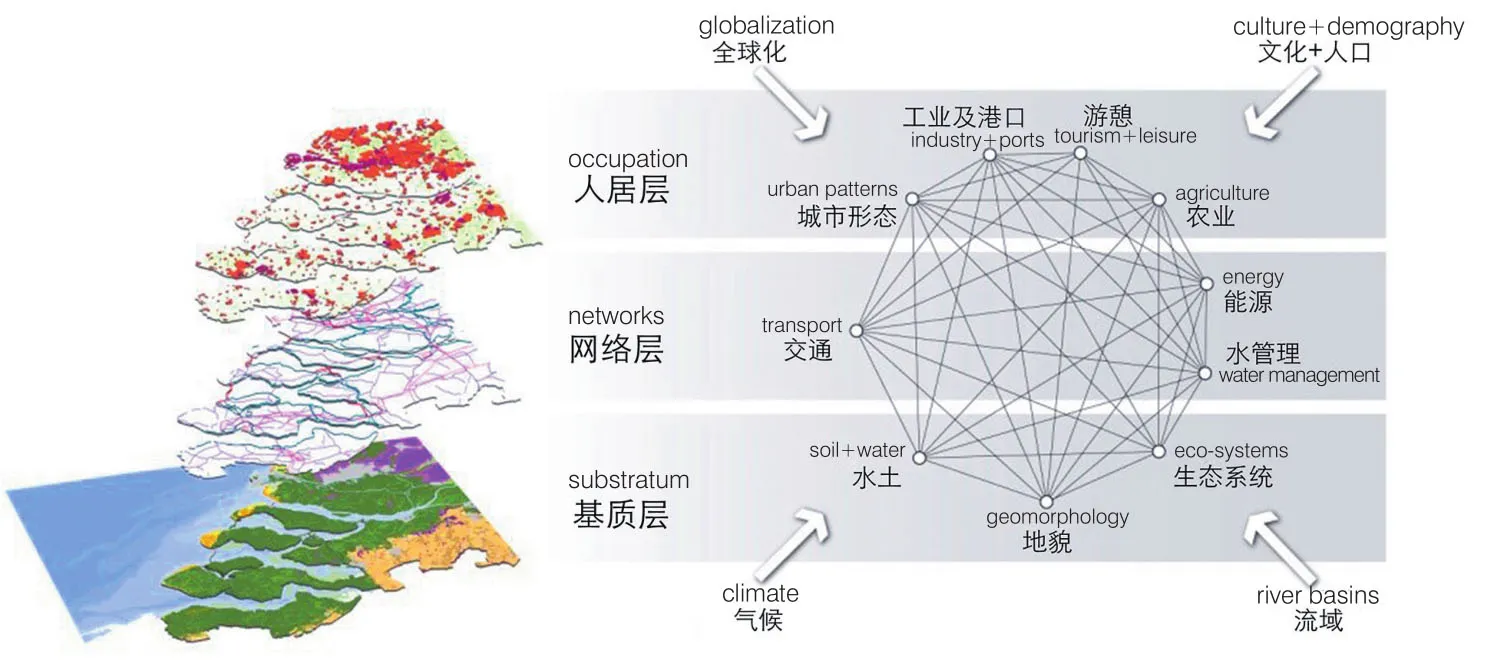

4 将城市景观理解为分层的复杂系统Understanding the urban landscape as a layered and complex system

5 公元前4000年至2015年珠江三角洲景观的形成Landscape formation of the PRD from 4000 BC to AD 2015

2 基于景观的区域设计

基于景观的区域设计将城市景观视为全纳性的动态复杂系统。在此视角下,空间发展通过生态区域的规划导则和设计导则的实施得以实现。这一方法建立在查尔斯·埃里奥特(Charles Eliot)[30]、沃伦·曼宁(Waren Maning)[31]、彼得·维尔哈亨(Pieter Verhagen)[32]、帕特里克·阿伯克罗姆比(Patrick Abercrombie)[33]、弗里茨·舒马赫(Fritz Schumacher)[34]、伊恩·麦克哈格(Ian McHarg)[35]、菲利普·刘易斯(Philip Lewis)[36]等人的观点和实践之上。

区域设计采用风景园林、景观生态学、地理学和建筑学的原则进行空间导向的研究、设计和规划。同时也利用系统思维和复杂理论推进更综合的区域规划设计,以涵盖构成城市景观的各种复杂关系网络[37]13-34。基于这些目的,区域设计为城市转型、生态多样性保护、水资源管理、休闲游憩、社区建设、文化认同和经济发展提供了一种模式[38]。

基于景观的区域设计包含2个部分:战略和干预。前者辨识并引领对区域可持续增长最有利的场所、功能、尺度和相互关系,后者在微观尺度创造积极条件[37]22。区域设计根据自然和城市景观生理和功能塑造区域的物理形态,并致力为未来发展创造条件。这种方法能在区域到地方之间的不同尺度运作,也能由普遍到特殊,既保持整体连续性又兼顾局部偶然性。它在各类国土之间提供了多种方式以平衡服务与质量间的关系[39]。

区域设计是着眼于保护和开发各种资源的开放战略。通过景观规划和设计的方式,为空间发展指导开发过程并创造前景条件[37]25。区域设计也设置了稳健且适应能力强的系统,这些系统既有韧性也能根据变化进行调整。区域设计的组织结构是以水系统和交通系统为代表的“强健”且联通的结构,这些组织结构能够支持区域发展,融入当地实际,经受各种挑战,也足以灵活地迈向未来[40]。

由于这种基于景观的区域设计承认城市肌理的集体性,并允许各类“作者”参与创作,使其成为一种社会全纳性的设计方法[41],为利益相关方和其他参与者指明了方向,使各方得以同心协力。由此,基于景观的区域设计成为一项跨学科的任务,工程专业和生态专业通过空间设计思维在此整合,本地居民的想法和知识也得到重视。因此,区域设计可以根据各要素的时空尺度特征,对自然环境、个体及信息、治理及其相互关系进行跨越时空尺度的组织[16]43-46。

基于景观的区域设计的核心是研究与设计的紧密互动。研究的分析能力与设计的探索能力密切相关。在设计前期,设计通常会借助一些研究形式来获得针对空间问题的基本方向和手段,而在这种方法中,设计过程本身作为视觉化空间问题的推动者,探索多种可能性,生成多样的解决方案。因此,结合设计的研究被视为有力的研究战略,通过创新型整体化方式来解决复杂的空间问题。这种目标明确的求索过程是区域设计的中心,思考和创作在此携手并进。研究和设计的各种机制中融入了想象、创造和创新,结合设计的研究将这些机制一一实现。其也可作为通过行动、观察和求索而获得洞见的理解方式。因此,图析和绘图成为视觉思考和沟通的重要工具[42]。

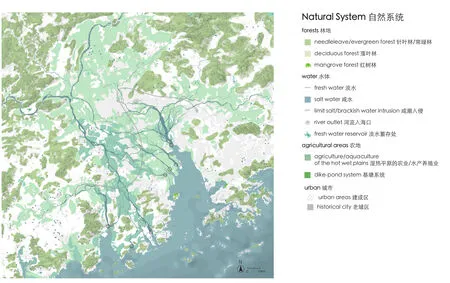

6 珠三角生态—农业系统图The eco-agricultural system of the PRD

3 区域设计过程的关键阶段

基于景观的区域设计过程包含至少4个迭代阶段:收集信息、获得理解、规划发展和行动展望(图3)[43]。

3.1 收集信息和获得理解

在设计过程开始之前,需要在对场地挑战和潜力的充分理解之上确立区域战略的目标。这不仅意味着收集、创造数据及信息,也意味着在多尺度上对区域进行分析和评价,后者还包括识别利益相关方。该阶段的问题包括:1)一个地区如何在微观和宏观尺度上运作;2)在不同尺度上有哪些决定区域的空间—视觉、历史、社会及生态结构和过程;3)城市和自然各系统如何运转。

上述问题的答案揭示了对设计要素的描述、选择和评价,并涵盖了综合性城市景观规划设计中的各个方面。在此过程中,通过设计者独自对信息进行解读、合成和应用,数据被转化为知识。在该过程中,设计者通过对数据和信息的探索、分析和合成,增进了对区域(各方面)在空间关系、结构和格局的理解程度。理解(洞见)是基于评价的认知,使知识提升效益,增加价值[44]。借助理解,设计者可识别国土的主要挑战和机遇,并勾勒出多种未来走向。设计过程不应该局限于听取专家咨询,也应通过交互工作坊、访谈、观察和问卷等形式,采纳政府官员和当地居民等其他利益相关方的意见。

3.2 规划发展和行动展望

在分析和评价阶段结束后,区域设计的主要挑战和机遇已经确定,继而是发展和探索众多整体性、多尺度的设计战略和导则,尤其需要关注这些战略和导则的潜力。需要解答的问题如下:1)如何应对该地区的挑战;2)如何通过多个尺度上的众多项目来开发区域的潜能;3)在区域尺度上有哪些需要注明和整体协调的空间关键结构和过程;4)在区域尺度上有哪些战略点,可安排哪些对其有利的条件;5)这些战略点和有利条件如何与区域内进行中的项目相联系;6)哪些重要的利益相关方能够保障社会经济和生态的扎根;7)是否具有借鉴意义的国际先例;8)如何使长期战略和短期设计干预互相关联、彼此扶持。

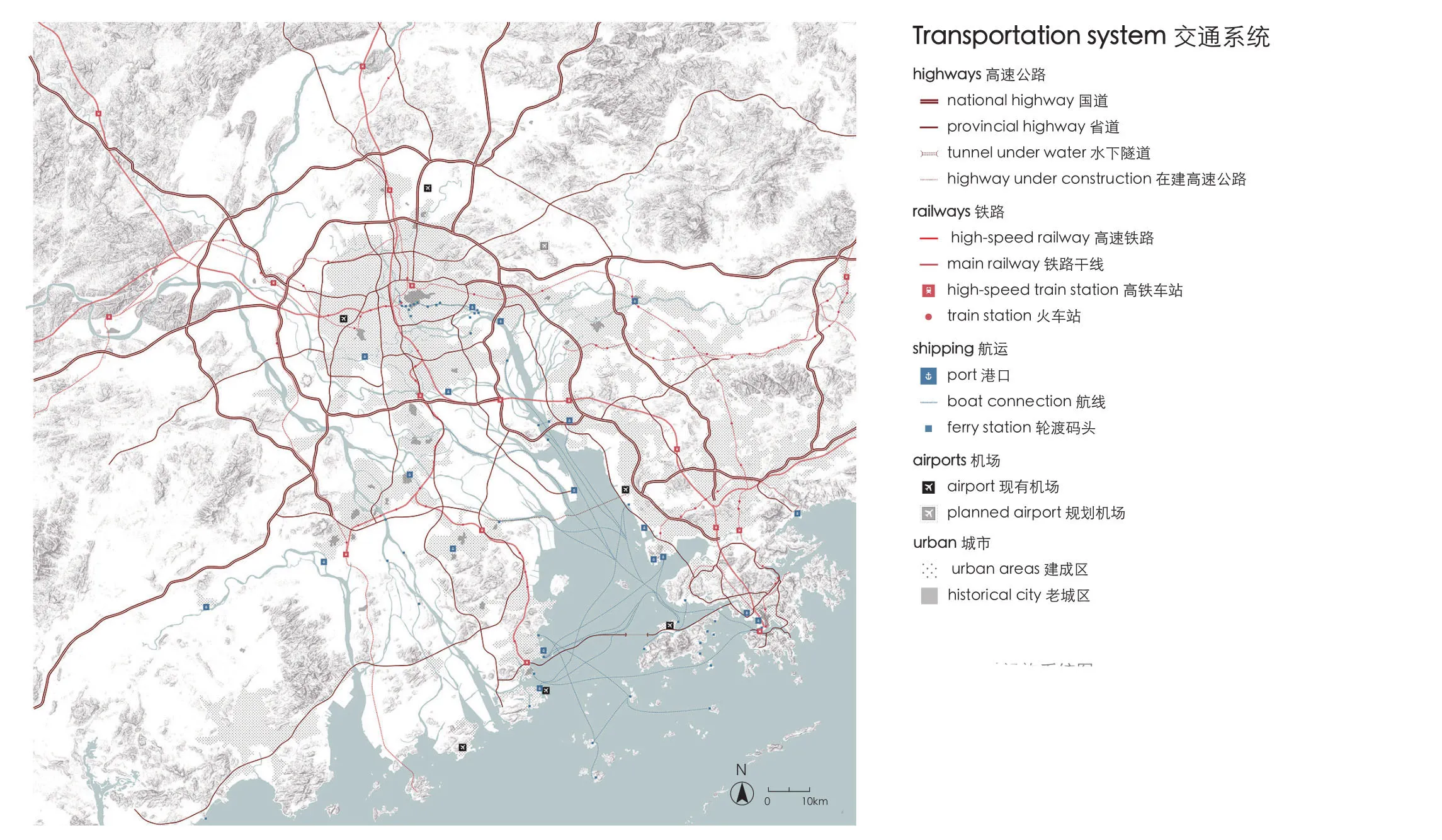

7 珠三角基础设施系统图A map summarizing the infrastructural system of the PRD

解答此类问题所采取的重要方式包括:先例研究、愿景建设、结合设计的研究等。设计性思维对探索设计战略和导则在空间上应用的可能性大有裨益。这部分的关键包括创新、创造和想象。设计战略和导则通过视觉化方式探索,其可行性由设计师、专家和利益相关方评价。计算机模型、现场试验、模拟等都是这个过程的组成部分,尤其是涉及产生观点、视觉化和测试的时候。该步骤涉及的问题包括:1)有哪些有用的空间规划设计战略和导则;2)这些战略和导则如何在区域应用,可能的结果如何;3)在空间、社会和生态视角上,有哪些优化方案;4)是否能在设计中包含某些历史层面;5)如何使规划适应并增强区域的认知度;6)设计能否在长时间内进行变更并具备灵活度;7)如何构成土地利用格局、植被、水、城市类型和其他要素,使其能够促进生态系统服务及文化表达。

区域设计不仅仅通过规划和设计技巧来优化、整合和组织物理结构,也体现了相关部门政策发展下的长期战略。通常需要在政府治理上做出新的配置来为区域设计创造条件,例如开发一系列微观项目。因此在规划早期,纳入相关决策者、政府部门和其他利益相关方就显得十分重要。

4 理解珠三角:一个复杂系统

珠三角的城市景观可以理解为一个复杂系统,其包含着多个子系统,各子系统具有独立的动态特征和速率变化[14]160-191。作为一个系统,城市景观是在网络和场所的交织中形成的物质空间,其中的网络和场所所属的组织层次繁多,具有显著的时空维度[45-47]。长时段(longue durée)的概念在此十分必要,因为其将城市景观视为一种持续变化的长期性结构。第一级动态与自然环境相连,其特征是几乎难以觉察的慢速过程,包括转型、重复和自然演替等;第二级动态与长期社会、经济和文化历史相连;第三级动态则是短期的人类和政治事件[48]。简而言之,在生态、社会文化和政治因素影响下,自然与人类在结构、格局和过程等层面进行持续不断的相互作用,进而产生了不断发展的城市景观。

4.1 图析景观系统

图析(mapping)是制图探索,可用于研究自然与人类互动所产生的空间关系,识别重要条件、关键驱动力和各显著性动态带来的影响。这种对景观系统进行的图析与麦克哈格[49]倡导的可持续性地图有所分别。图析着重于理解众多空间关系及动态的变化,这些关于空间条件的知识并不一定能推导出适建地区,但是能够协助形成适应性规划战略和设计导则。根据动态的变化对城市景观进行逐层分解是理解城市景观系统的有效方法[50]10-22(图4)。低速动态变化的层面是基质(如地形、水文、土壤)和气候(如降水类型、温度、风)。这些环境条件对土地利用最具影响力,因此称为第一级条件。位于中速动态变化层面中的第二级条件包括交通、水利、能源等基础设施网络,这些条件对土地利用影响显著。相对于一级条件,二级条件的增长和变化更快,为农业土地利用和城市定居铺平了道路,产生了高速动态变化转型的层面[50]19。

4.2 图析珠三角的自然和城市系统

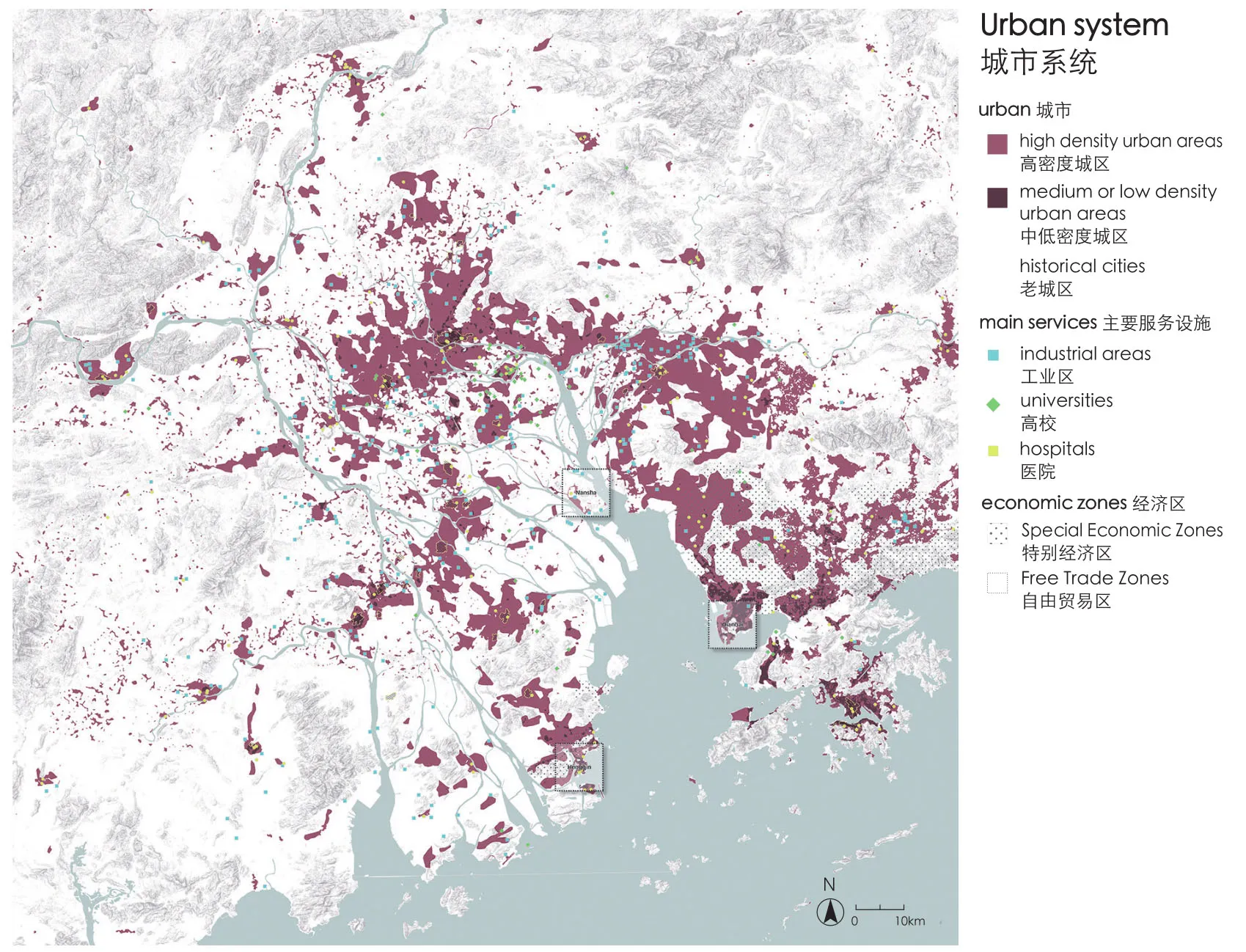

为了理解珠三角的自然和城市系统,本文笔者制作了一组地图以掌握国土各动态层面、自然和城市系统及其相互作用。总结了描绘珠三角特征的主要物理结构和格局,包括生态-农业系统、城市系统、基础设施网络和城市肌理及其相互关系。

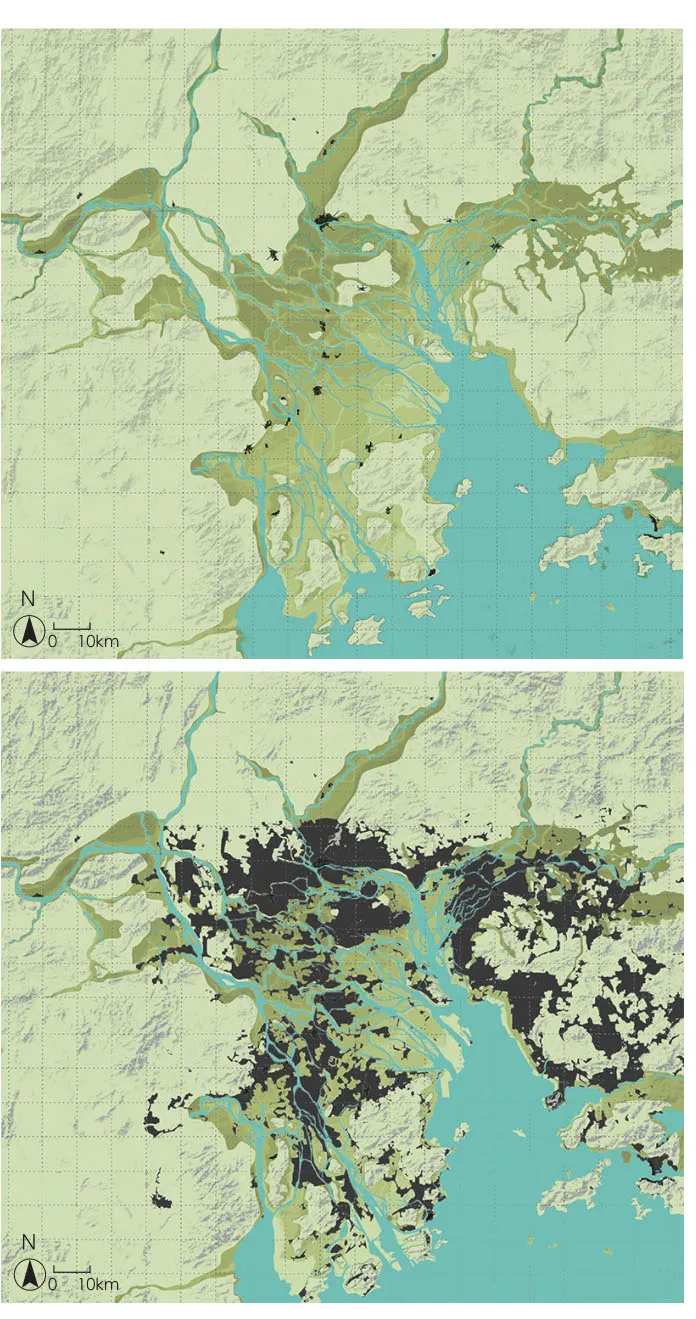

8 1950—2015年城市发展Urban development from 1950 to 2015

9 珠三角城市肌理结构图A map summarizing the structure of the urban tissue in the PRD

自然系统取决于气候、地貌、水和岩型。这些自然要素驱动土壤形成,确定水文,生态系统、农业土地利用、历史聚落和城市的分布。珠三角可根据地貌特征分为2个部分:西部是经历数千年来淤积和沉积过程形成的河控型三角洲,东部河口则为潮控型三角洲(图5)[51]156,珠三角80%以上的土地是平原,有160余个岛丘,另有187个岛屿分布在近海[51]155。其三角洲低地的特点是2个次级三角洲和一个潮控河口。西江、北江和东江主导着珠三角,其流域面积453 690 km2,干流总长2 200 km。西江是最重要的水沙来源(占80%径流量和90%输沙量)。西江和北江次级三角洲的洪水期在4—9月。7—9月间,河口区域受到台风等热带风暴所带来的风暴潮威胁。

珠三角湿润平坦,这样的自然气候和地理条件是湿地生态、城市发展和农业生产的重要基础。此地的农业活动可以追溯到4 000多年以前。在这个由频繁的洪水和持续的泥沙沉积所形成的不断变化的湿地环境中,人与自然形成了可持续发展的关系[52-53]。湿润和平坦的地形特征使当地居民经过长年累月形成了一套复杂的多尺度水敏性途径——种植业与水产养殖相结合。该途径长久以来作为当地经济生产的基础。其中最值得一提的是产生于14世纪的次级三角洲中的基塘系统:四周堤围种果树,中间水塘养鱼[54]。17世纪早期,这种模式发生改变,桑树和四大家鱼的组合振兴了当地的丝绸和渔业经济。从此,这种种植业与水产养殖业结合的模式延续到了20世纪20年代[55]。如今,大部分种植业与水产养殖业结合地区发生了转化,或成为单一的渔业养殖,或成为工业片区和城市。

珠三角的自然植被由重要的海湾带和河岸带主导,在这些区域中包括了多种红树林、湿地和湿润森林类型。在山区以多种干旱森林类型为主,一些地区的原生植被遭到砍伐,并在近期得到再植。坡脚地区拥有能够提供淡水和灌溉的淡水集水区(图6)。

该区域在各历史时期非常依赖水上交通。从20世纪50年代起,土地所有权从私有变为国有或集体所有,这使得珠三角在区域尺度发展基础设施成为可能。大尺度堤围的改造[51]156、(高速)铁路网络的铺开和公路里程的持续增长成为城市快速扩张的重要条件。在广州—深圳(香港)和广州—珠海(澳门)的廊道上均有优良的公路铁路基础设施。重要的交通枢纽包括香港和南沙的海港,以及香港和广州的空港(图7)。

包括广州、佛山和澳门等在内的历史名城可以追溯到2 000多年之前。以广州为例,考古发现的规模可观的王宫御苑,展示了南越国在公元前约203年左右丰富的文化[56]。值得一提的是,广东省的岭南园林和传统建筑适应了特殊的气候条件,在选址、朝向、布局和实际建造方面都主动营造微气候。由于战略和交通原因,这些历史城市的核心地区都与河流和海洋相连。

自20世纪50年代起,历史城市开始受到基础设施建设的影响。从20世纪80年代起,中国在珠三角建立特别经济区以吸引外资,珠三角也开始成为世界上城市化最快速的三角洲区域(图8)[50]。该区域在关税、金融和税收上获得了一定程度的自主权。制造业公司开设工厂,创造了富有活力的经济区域。在城市化过程中,大面积的圩田地区由农业用地转为城市用地。根据广东省2016统计年鉴,珠三角拥有6 000万人口,并将在2030年增长到8 000万。

城市发展的空间模式因地而异。北部的城市化呈现出围绕历史城镇中心的同心圆模式。东部的城市化以线性模式沿着海岸线发展并受山脊限制。西部由圩田城市化产生了分散模式。目前城市化集中于广州—深圳的城市廊道,南沙作为连接口岸具有重要的地位(图9)。

综合图(图10)展示了在环境条件(如基质和气候)和基础设施网络(交通、水管理和能源)相互作用下的城市景观。这些条件为农业用地和城市定居点的发展铺平了道路,而后者则带来了最高级别的变化和转型动态层面。然而,快节奏的城市化与气候变化在城市中产生了严重问题。除了海平面上升之外,台风引起的空前风暴潮和增长的河流径流量导致了城市区域频繁的洪涝。渠化的河流失去蓄洪空间,水安全受到威胁。相当一部分农业用地转型成工业用地及城市区域,失去了调蓄雨水的能力。原生红树林的消失使得海岸线更易遭受洪水威胁。除了洪涝之外,珠三角还遭受着一系列威胁:流失的生态和文化—历史价值、地层下陷、咸潮入侵、用于食物生产的农业用地流失,以及众多社会—经济问题等。

5 迈向珠三角可持续发展的未来

基于景观的区域战略,以适应性城市转型作为基础来正视珠三角的主要挑战和潜力。在这种战略中,针对从多系统分析中提炼出的多种自然和城市动态,必须调节其适应性的节奏和性质。规划发展和行动展望将聚焦在尺度的角度以连接经济和生态发展的潜力,使规划得以顺利开展。目标是为旧工业(居住区)和受到建成区扩张限制之下的区域农业景观提供可持续的转型,使其能够容纳经济和人口的增长。这些地区具有特别的空间条件,适于长期的经济发展。与此同时,这些地区通常位于三角洲河口的新围垦之地,该地河网密集,鱼塘密布,湿地和农业为高敏感的生态系统,易受洪涝威胁。在这一阶段识别出区域蓝绿基础设施和城市级水网的发展可能性,以提升区域的适应能力、生态系统服务功能和水安全。

10 珠三角城市景观The urban landscape of the PRD

5.1 愿景研究

笔者进行了愿景研究来调查珠三角可能的未来发展。通过结合现实和想象,识别关键位置、驱动力和未来事件的预期影响,这些既是机遇,也是挑战(图11)[1]293-312。愿景作为有用的工具,可以解决未来发展趋势的不确定性,并理解各种发展趋势及其之间的联系、新的挑战和政策以及政策成效,也能建立并促进各利益相关方参与战略性对话[57],[58]11-13。目前为止各种愿景都是在学术环境下制定的,政府机构和水务局也包含在内。愿景的完善需借助制定假设集合的方式。这个包含多条假设条件的集合根据已发现的各种主要相互作用关系而制定,且必须自洽和自相干。在这些假设之上,可以依据现有愿景系统地进行选择性描述,并识别决定空间发展走向的最显著外部变量[58]11-13。

11 探索珠三角空间发展的未来愿景Exploring future scenarios for the spatial development of the PRD

12 使用电脑制图桌共同思考珠三角的未来Thinking together about the future of the PRD using a digital map table

5.2 发展区域的战略视野

珠三角战略视野的雏形由主导未来发展的因素决定,这些因素通过2种评价相结合:1)随时间推移的城市景观增长评价,2)区域现有空间发展项目评价。这个战略视野需要根据以下基本设想进一步深化:珠三角将成为中国的硅谷,拥有交通便捷的城市品质,健全的蓝绿框架,乡土的文化—历史资产,以及水敏型社会—生态全纳的城市性。根据东翼(广州—香港一线)现有规划,珠三角将继续发展成为连接通达的“红—绿项链”,山海之间将形成强有力的城市口岸和港口以及健全的绿色廊道。西翼则将受益于湿润平原的特征,发展成结合水敏性生态农业—水产业和蓄洪区域的蓝色轴线,并以交通导向发展形成的强健的城市口岸为补充。

5.3 转型视角

区域战略视野主要用于确定空间规划设计中的优先权。通过返测(back casting)识别空间转型视角,以协助完成由战略规划设定和引导的目标。空间转型视角提供了一套适应性设计战略,这套战略是根据珠三角2个次级三角洲和1个河口的国土上的挑战和潜力定制而成。每一个转型的视野具有以下视野之一:水敏和社会—生态全纳、多时空尺度下的灵活和多功能。在2个次级三角洲上,转型视野与河流和雨水适应性途径相联接。其包含以下设计导则:韧性河流设计;农业—水产养殖业一体化;可持续城市转型;新城区、历史村落整合;工业转型和生态旅游等。在河口上,转型视野主要与海水适应性途径相连接。其包含以下设计导则:多功能防洪;港口和码头发展;围垦(沉积与侵蚀);水岸发展和转型以及红树林和其他海岸生态系统的保护及开发。

各项转型视角均须深化。设计导则需要通过对相关成功国际案例的研究而形成。此外,它们的潜在需求须通过研究结合设计的过程来探索。这些设计导则的可能性可以通过空间和视觉的方式以战略性地区作为实验场进行测试。读者可在孙传致等[59]一文中了解农业—水产养殖业一体化这一设计导则在珠三角多尺度水敏性设计中的深化。

5.4 行动展望

为了将获取的知识和想法转化成行动,需要为新型治理创造条件。因此区域设计将猜想也包含在内,以促成各利益相关方之间的互动,完成合作、共同设计和微调设计的过程。如上所述,2种评价对区域设计过程至关重要,包括针对现有城市规划战略和项目的建成后评价,以及针对潜在适应性战略愿景的预评价。区域设计过程必须通过这2种评价,理解城市景观各动态并促进其转型[5]3-4。交流是将本地利益相关方和决策者纳入的核心,因此发展和利用创新型视觉化方法和工具十分关键。针对利益相关方的访谈和工作坊贯穿于整个过程之中,以探讨达成共识的可能性。在工作坊中,利益相关方围绕在电脑制图桌周围理解各系统的相互关系(图12)。除了电脑制图桌外,其他视觉化手段还包括增强现实技术和虚拟现实技术[60]。参与者可以看到其行为在其他系统上可能产生的影响。这些创新型的视觉化手段大大加速了所有利益相关方关于各种提议的讨论,并将进一步发展区域视野和相关战略。转型视野将引领三角洲的发展,使其通向更可持续的前景。

6 结语

综上所述,珠三角的城市景观是多种过程和系统的产物,这些过程和系统拥有不同的变化动态且相互影响。相互连接系统及其外在形态是当今区域发展的基础之一。因此,通过空间设计将系统联系起来的能力变得愈发重要。

在珠三角的适应性转型中,我们提倡将基于景观的区域设计作为一种全纳性的规划设计方法。本文不仅描述了其结果,也阐释了这一方法。在挑战接踵而至的时代,此类方法的提出使不同的理解方式、社会—生态全纳性设计过程以及不同学科和利益相关方的合作模式成为可能。基于景观的区域设计促进了设计学科间的合作,如建筑、城市规划和风景园林等,也通过塑造建成环境来检视空间设计的效果。此外,这种全纳性的设计方法得以建立多对关系,如生态与文化、过程与形态、长期发展与短期发展、区域战略与本地干预等。因此,基于景观的区域设计是指导国土转型强有力的媒介,是其兼顾本地认同的产生和区域关系的保障,同时将生态、社会过程与城市形态联系起来。

在这种思路下,基于景观的区域设计提供了新的运作能力,使空间设计成为一种整体性的创意行为,也将区域城市景观作为重要的探索领域。在此之中的探索由文脉而驱动,以方案为焦点,并且跨越学科。

致谢:

感谢格利高里·布拉肯博士所作的英文编辑。

图片来源:

图1由谢光源摄;图2基于SRTM(30 m)和Hydropolis由斯特芬·奈豪斯绘;图3来源于参考文献[37];图4由斯特芬·奈豪斯绘;图5、8来源于参考文献[50];图6、7、9、10由斯特芬·奈豪斯、丹尼艾勒·坎纳特拉、熊亮绘,数据来源于SRTM(30 m)、Hydropolis、谷歌地图、百度地图、开放街道图(OSM,2018.4),其中土地利用数据源于世界生态土地单位地图(250 m,WorldELU,2015)、Globeland30(2010)、港口数据源于世界港口指数数据库(WPI,2018.4),老城区数据源于参考文献[50];图11、12由斯特芬·奈豪斯摄。

Urbanizing deltas are among the most promising and dynamic regions of the world.They play a significant role in both the world’s ecosystems and the global economy[1]293,[2]. They accommodate large concentrations of population in particularly sensitive environments that are dominated by water systems. As a result, these deltas face extreme vulnerability and multiple threats[3-4]. This is because the intensification of urban land use and economic activity within a sensitive water environment is a difficult situation to manage. In the absence of effective governance,the outcomes of this management are often a combination of ecosystem damage and the loss of socio-cultural values. This weakens the capacity of deltas to resist natural hazards, and the risks associated with climate change. These effects have consequences for the environment, the economy of the deltas, and the health and prosperity of citizens that live around these water systems[5]2-3.

Urbanizing deltas can be understood as a set of complex social-ecological systems and subsystems, each with their own dynamics and speed of change (Fig. 1). To ensure a more sustainable future, spatial strategies are needed in order to strengthen resilience, assist systems to cope with their vulnerabilities, and strengthen their capacity to face natural and human-made threats. These strategies will need to address the interrelation of systems by helping to avoid damaging contradictions,such as when urban development increases the risk of flooding. Strategies like these can draw attention to the potential of ecologically sensitive urban development that ensures economic and social growth, while also providing opportunities for the strengthening of natural systems and water safety[5]3-4. Concurrently, a spatial strategy such as this must involve a wide range of social and economic actors, while also supporting the social, economic,and cultural conditions of the local inhabitants.These strategies should be communicated in ways that are persuasive so that they may gain wide understanding, support, and influence[6-7].

At the same time, it is not only necessary for these strategies to improve the living conditions within urban deltas, but to also adapt to climate change in order to decrease the risk level of these areas. The urban planning and management necessary to create more resilient deltas require a certain degree of adaptive capacity. Their strategies must also identify eco-dynamic design options that not only provides opportunities for the integration of nature alongside urban development processes, but also implements adaptive design principles that ensure water safety.In addition to this, there is a need to integrate transformative processes in governance that combine spatial planning, design, and disaster management.Doing so will allow for the optimization of landuse, institutions, and mechanisms for an efficient,sustainable, and inclusive urbanization[5]6.

From the 2000s onwards, there have been serious attempts to develop an adaptive systems approach towards the planning and designing of urbanizing deltas. Examples of these attempts include the Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt (RMS) Delta in the Netherlands[8-9], the Mississippi River Delta in the United States[10-11]and the Mekong Delta in Vietnam[12-13]. This paper and the related research suggests that there is a much greater potential benefit in using urban landscape dynamics in territorial governance, as opposed to more traditional planning strategies[1]293-312,[14-15].The paper also elaborates on a landscape-based regional design approach for an adaptive urban transformation of the urbanizing deltas. It not only uses the Pearl River Delta as an example of this, but also focuses on the description of the approach itself. Therefore, this paper outlines an integrative approach towards the planning and designing of urban landscapes, where natural and urban dynamics must set both the pace and nature of adaptation required for adaptive urban transformation (AUT)[5]6.

AUT employs landscape-based regional design methods as an integrative and multiscale design and planning approach. Doing so can steer urban and rural transformative processes through a combination of sector activities aimed towards more coordinated sustainable outcomes.Landscape-based regional design is considered to be an important strategy that shapes the physical form of regions by using landscape as the basic condition to generate sustainable urbanized deltas.It also provides ways for long-term sustainable urban landscape development through both spatial planning and design. In summary, regional design is a transdisciplinary effort that not only safeguards sustainable and coherent development, but also guides and shapes changes that are brought about by socio-economic and environmental processes,while establishing local identity through tangible relationships to a region[16]43-46.

1 Pearl River Delta

The Pearl River Delta (PRD) in China has been the fastest developing delta in the world for the past four decades. In 2014, it even surpassed Tokyo to be the world’s largest urban area in regards to both size and population[17]. The PRD has led to groundbreaking changes in Chinese urbanization and socio-economic transformation changes since the 1980s[18]. In spite of this, the PRD faces immense challenges regarding its long term economic development because of the threats posed by climate change and environmental degradation. These challenges include issues such as mangrove disappearance[19], agriculture land loss[20], air and water pollution[21], water shortage[22],and a decrease in social security[23].

On the one hand, the region is exposed to increasing flood risks due to urbanization in flood prone areas (Fig. 2) due to rising sea levels and extreme typhoons and storms in summer, which put stress on infrastructure systems of the region.On the other hand, the ecosystem is becoming increasingly fragmented and vulnerable[24], which is characterized by a decline in both ecological services[25]and environmental carrying capacity[26].At the local level, large scale interventions have replaced the diverse historical environment and cultural heritage of the PRD, with more uniform space that lacks any sort of distinctiveness[27]. There is, however, an increasing awareness by authorities and authorities of the value in more integrated planning and design approaches, but they have not been so widely introduced yet[28]. For example, the implementation of the so-called national “Sponge City” policy — a concept that focuses on integrated urban water management — has met with delays in the elaboration of both multiple and separate sectoral plans[29].

In order to guide the PRD towards a more sustainable future, there is an urgent need for new ways of planning and design in the practice of its urban development. The emerging concept and practice of landscape-based regional design offers a way to tackle the conflicts and threats between economic development, environmental recovery,and risks associated with climate change. The high speed in which the PRD has developed makes it a particularly valuable case where the potential of more adaptive integrated planning approaches,such as landscape-based regional design, can be experimented and explored.

2 Landscape-based Regional Design

Landscape-based regional design aims to afford spatial development by applying bioregional planning and design principles that regard the urban landscape as an inclusive, dynamic and complex system. Landscape-based regional design builds on ideas developed and applied by Charles Eliot[30], Waren Maning[31], Pieter Verhagen[32],Patrick Abercrombie[33], Fritz Schumacher[34], Ian McHarg[35]and Philip Lewis[36].

Regional design uses principles from landscape architecture, landscape ecology,geography, and architecture for spatial oriented research, design and planning. It also utilizes ideas from both system thinking and complexity theory to promote a more comprehensive type of regional planning and design that addresses the complex relationship webs that make up the urban landscape[37]13-34. For these purposes, regional design offers a mode for urban transformation,preservation of biodiversity, management of water resources, leisure, community building, cultural identity and economic development[38].

Landscape-based regional design identifies and guides the most advantageous places,functions, scales and inter-relationships for a region’s sustainable growth — strategy — and sets the scene for local initiatives — intervention[37]22.Regional design forms the physical shape of regions based on knowledge of the natural and urban landscape physiology and functioning, and focuses on generating circumstances for future development. This type of approach also operates on different scales, ranging from regional to local,and from general to particular, while preserving overall continuity and promoting local contingency.It also offers ways of balancing out the services and qualities between parts of a territory[39].

The regional design is like an open-ended strategy that is aimed at protecting and developing resources. This is achieved by guiding developments and establishing future conditions for spatial development by means of landscape planning and design[37]25. It also sets up robust and adaptive systems that are resilient and open to change. The organizational structures — “strong” and coherent structures such as water and transport systems —provide the backbone for regional development as well as adapt to local circumstances and withstand challenges, but also sufficiently flexible to develop into future situations[40].

Regional design based on landscape is a social-inclusive approach as it acknowledges the collective nature of the urban tissue and enables various “writers” to participate[41]. The regional design generates a directed field where various stakeholders and other participants can contribute to its development. In this regard, landscape-based regional design is a transdisciplinary undertaking where engineering and ecology specializations merge with spatial design thinking, but also involve local residents’ thoughts and knowledge. Regional design can therefore be regarded as an integrative platform that organizes physical environment,individuals and information, governance, and their interaction at distinct scales through space and time[16]43-46.

At the heart of landscape-based regional design exists a strong interaction between research and design. This implies that the analytical capacity of research is closely connected to the explorative power of design. Next to typical forms of research that serve as input for the design, the design process itself is employed as a vehicle to not only frame spatial problems visually,but to explore multiple possibilities and generate various solutions. Therefore, research through design can be regarded as a powerful research strategy in which complex spatial problems are approached in a creative and integrated manner.The targeted search process plays a central role in which thinking and producing go hand in hand.Research through design implements mechanisms of research and design that are combined with imagination, creativity, and innovation. It is also used as a way to understand where action,observation, and searching can be used in order to achieve new insights. Therefore, mapping and drawing are important tools for visual thinking and communication[42].

3 Key Phases in the Regional Design Process

Landscape-based regional design consists of at least four iterative phases: collecting information,gaining understanding, plan development, and action perspective (Fig. 3).

3.1 Collecting Information and Gaining Understanding

Before the start of the design process, the objectives of the regional strategy need to be identified and based on a proper understanding of the site, including its challenges and potentials. Not only does this means the collection and creation of data and information, but it also means the analysis and evaluation of the region at multiple scales,which includes the identification of all relevant stakeholders. The questions one should ask at the beginning of this process includes: 1) How does an area operate on a local scale level, and how does it function in a larger regional context; 2) What are the spatio-visual, historical, social, and ecological structures and processes that determine the region at different scales; 3) How does both the urban and natural systems work.

Answering questions such as the ones mentioned above implies the description, selection,and valuation of the elements, while also including aspects that matter in comprehensive urban landscape planning and design. It is a process where data becomes knowledge in relation to an individual interpreting, synthesising, and applying information.The process is about exploring, analysing, and synthesising data and information in order to increase the level of understanding on (aspects of) the region in terms of spatial relations, structures, and patterns.Understanding (or “insight” ) is the application of knowledge, increasing effectiveness, and adding value by judgement[44]. It enables the application of knowledge to identify the main challenges and opportunities of the territory, while also outlining alternative futures. The design process should also not only just get the consultation of experts, but it should also include the input of other stakeholders,such as governmental officials and people living in the region. This can be done via interactive workshops,interviews, observations, questionnaires, etc.

3.2 Plan Development and Action Perspective

As soon as the analysis and evaluation phase is finalized, and the main challenges and opportunities are determined, various integral and multiscale design strategies and principles need to be developed and explored, especially in regards to their potential.The questions that need to be answered involve the following: 1) What can be done to address the challenges of the area; 2) How can the potential of the region, by means of projects at multiple scales,be exploited; 3) What are spatial key structures and processes that need to be addressed and coordinated integrally at the regional scale; 4) What are strategic locations, and what are the favourable conditions that can be arranged at the regional scale; 5) How does that relate to the on-going projects in the region; 6) Who are the important stakeholders that should be involved to ensure social-economic and ecological embedment; 7) Are there any informative(international) precedents; 8) How can long-term strategies and short-term design interventions interrelate and strengthen each other.

In order to address these type of questions,precedent study, scenario building, and research through design are important means that can be used to answer them. Design thinking is also useful to explore the spatial possibilities of the application, in regards to various the design strategies and principles. The keywords this part of the process are innovation, creativity, and imagination. Design strategies and principles are also explored in a visual way, while also being evaluated on their feasibility by designers,specialists, and stakeholders. Computer models,field experiments, modelling etc. can also be parts of this process, especially in regards to generating ideas, visualization, and testing. The questions that need to be addressed in this phase include: 1) What are any useful spatial planning design strategies and principles; 2) How can they be applied at multiple scales in the region, and what will be the probable outcome; 3) What is the optimal solution from a spatial, social, and ecological point of view; 4) Is it possible to include any historical aspects in the design; 5) How can the plan adapt to the identity of the region, and strengthen it as well; 6) Does the design allow for change and flexibility over time;7) How can the composition of land use-patterns,vegetation, water, urban typologies, and other elements facilitate ecosystem services, as well as cultural expression.

The regional design is not only a platform that prioritizes, integrates, and organizes physical structures that make use of planning and design skills. It is also an implementation of a longterm strategy that requires policy development by responsible authorities. However, new governance arrangements often need to be developed in order to set conditions, such as the development of local projects, for example. Therefore, it is important to involve relevant policymakers, governmental authorities, and other stakeholders who already need to participate in early stages of the planning process.

4 Understanding the PRD as a Complex System

The PRD’s urban landscape can be understood as a complex system consisting of subsystems.Each of them has its own dynamics and velocity of change[14]160-191. The urban landscape as a system is a material space that is structured as a constellation of networks and places with various organizational levels that address distinct spatial and temporal dimensions[45-47]. Here, the concept of longue durée is essential as it is about understanding the urban landscape as a long-term structure that is constantly changing. The first level of dynamics is connected to the natural environment and is characterized by a slow process of almost imperceptible transformation, repetition, and natural succession.The second level of dynamics is linked to longterm social, economic, and cultural history. The third level of dynamics is that of short-term human and political occurrences[48]. In short, the urban landscape is an ongoing development that is the result of action and interaction between natural and human structures, patterns, and processes that depend on ecological, socio-cultural, economic, and political factors.

4.1 Mapping Landscape Systems

The spatial relationships between environmental circumstances and human reactions and interventions can be studied through cartographic explorations —mapping — to identify important conditions, critical driving forces and the effects of distinct dynamics.Mapping landscape systems as such is different from the suitability maps as proposed by McHarg[49]. This because the mapping is focused on understanding spatial relationships and the dynamic of change,and not necessarily indicating areas where e.g. urban developments can take place. Rather, it reveals the spatial conditions that can inform adaptive planning strategies and design principles. Decomposing the urban landscape in layers according to the dynamic of change is a proven method for gaining understanding the urban landscape system (Fig. 4)[50]10-22. Layers with a low dynamic of change are substratum(e.g. topography, hydrology, soil) and climate (e.g.precipitation patterns, temperature, wind). These environmental conditions are regarded as the most influential conditions for land use and are known as first tier conditions. Infrastructural networks for transportation, water management and energy supply are grouped in another layer and indicated as second tier conditions. These are also significant conditional variables for land use, but their growth and change is quicker than environment the first tier conditions.These conditions together pave the way for the development of agricultural land use and urban settlements, resulting in the layer with the highest change and transformation dynamics[50]19.

4.2 Mapping the Natural and Urban System of the PRD

In order to understand the natural and urban system of the PRD, several maps have been made to get a grip on the dynamic of the territory, the natural and urban system and their interactions. The three maps that were made summarizes the main physical structures and patterns that characterize the PRD which are the eco-agricultural system,the urban system, the infrastructure networks and urban tissue, and their relationships.

The natural system is based on climate,landforms, water and rock type. These physical factors drive the formation of soils, determine hydrology and the distribution of eco-systems,agricultural land-use and historical settlements and cities. The PRD can be divided into two parts which have different types of geomorphology. The western part of the delta is a river-dominated plain that has been formed by natural processes such as siltation and deposition, for over a millennium. The estuary in the east is tide-dominated (Fig. 5)[51]156.Almost 90% of the land in the PRD is a flat terrain comprised of 160 hills and 187 islands that is spread around the coast[51]155. The deltaic lowland is characterized by two sub-deltas and an estuary with tidal influence. The rivers that dominate the PRD are the Xijiang River, the Beijiang River and the Dongjiang River. Together, they cover a drainage area of 453,690 km2and have a total length of 2,200 km. The most important river in terms of water discharge and sediment load is the Xijiang River (80% of the water discharge, 90% of the sediment load). Seasonal flooding is a common characteristic in the Xijiang River and Beijiang River sub-deltas mainly during the period from April to September. The estuary also suffers from extreme tides induced by typhoons or storm surges that mainly occur in typhoon season which ranges from July to September.

In the PRD, the wet and flat characteristics are important conditions for wetland ecology, urban development and agriculture. It is notable that more than 4,000 years of extensive agricultural activities have taken place here. This has proven to be a sustainable human-environment relationship in the ever-changing wetland environment that has resulted from frequent flooding and the continual seaward extension[51-52]. Over the years, due to the wet and flat conditions of the terrain, the inhabitants have developed a sophisticated multiscale water-sensitive approach known as agri-aquaculture in the warm hot plains. This was for a long time the basis for local economic production. One of the most notable approaches is the dike-pond system found in the sub-deltas that was developed from the 14th century onwards with fruit trees planted on dikes with fish ponds in the centre[54]. This changed in the early 17th century where a combination of mulberry and four major fish species were utilized and had created a local silk and fisheries economy. Since then, this type of agri-aquaculture pattern continued to grow and prosper until it hit a peak around the 1920s[55].Nowadays, most of these areas have transformed into fish ponds for only fish production, industrial plots and urban tissue.

The natural vegetation in the PRD are defined by important bays and riparian zones which consists of mangrove forests, wetlands and wet forests. Individual mountains and ridges are home to dry forests. However, many of these have become deforested and in recent events, the process of replanting the trees has started. On the foot of the slopes, fresh water basins have been created for fresh water supply and irrigation (Fig. 6).

In historical times, the region heavily relied on transportation over water. From the 1950’s,the change of land ownership from private to state-owned has enabled large scale infrastructure development in the PRD. Large-scale dike reconstructions[51]156, the development of a vast network of (high-speed) train connections and an increase in road infrastructure has been important conditions for the rapid urban extension in the region. Well-developed road and train infrastructure can be found in the corridors from Guangzhou-Shenzhen/Hong-Kong and Guangzhou-Zhuhai/Macau. Important transportation hubs are the ports of Hong Kong and Nansha and the international airports of Hong Kong and Guangzhou (Fig. 7).

Historical cities such as Guangzhou, Foshan and Macau have a long history that dates back to more than 2,000 years. In Guangzhou for instance,archaeologists discovered the visible remains of a sizeable royal garden and palace showcasing the rich culture of the Nanyue kingdom that dates back to about 203 BC[56]. A notable detail is that the historic Lingnan gardens in the Guangdong province and its traditional architecture have adapted to specific climatological circumstances in terms of allocation, orientation, layout and materialisation that have positively influenced the micro-climate. The historical cities cores are all related to the river and sea for strategic reasons and transportation.

From the 1950’s onwards, the historical cities have been influenced by infrastructural investments.Since the 1980s, China created the PRD Special Economic Zone to attract foreign investment and the delta turned into the fastest urbanizing delta in the world (Fig. 8)[50]. It gave the area a certain degree of autonomy in terms of customs, finance and taxes. Manufacturing companies opened factories and had created a vibrant economic region. During the process of urbanization, large areas inside the polders transformed from farmland into urbanized areas. Presently, there are now 60 million inhabitants according to the Guangdong Statistical Yearbook 2016, and the PRD expects to reach a population of 80 million by 2030.

The urban development followed different spatial patterns. In the North, urbanization occurred in a more concentric pattern around the historic town cores. In the East, urbanization occurred in more linear developments that followed the coast line but has been limited by mountain ridges. Finally, in the West, dispersed patterns have been observed as a result of the polder fields that were used to urbanize. In terms of urbanization,the main focus is now on the urban corridor in Guangzhou-Shenzhen, with an important role for Nansha as connection hub (Fig. 9).

The synthesis map (Fig. 10) shows the urban landscape as the result of the interaction between environmental conditions (e.g. substratum and climate) and the infrastructural networks for transportation, water management and energy.These conditions have paved the way for the development of agricultural land uses and urban settlements which has resulted in the layer with the highest dynamics of change and transformation.However, the fast pace of urbanization and climate change has caused severe problems in the region.Next to sea-level rise, unpreceded storm surges caused by typhoons and increased water discharges by the rivers have resulted in frequent floods in urban areas. Water safety is under threat by the canalization of rivers which also lacks in flood storage. Sizeable stretches of agricultural land have been transformed into industrial sites and urban areas, and thereby lose their absorption/storage capacity for keeping rain water and ability to mitigate abundance and shortage of water. Natural mangrove forests have disappeared while making the coast line more vulnerable to flooding. Besides floods, the PRD also suffers from the loss of ecological and cultural-historical values, subsidence,salt water intrusion, agriculture land loss for food production and socio-economic problems.

5 Towards a Sustainable Future for the PRD

Adaptive urban transformations are the basis for a landscape-based regional strategy to address the main challenges and potentials of the PRD. In this strategy, natural and urban dynamics as derived from the systems analysis must set the pace and nature of adaptation. Plan development and the action perspective on how to make the plan work will focus on the potential of connecting economic and ecological development at multiple scales. The goal is to facilitate sustainable transformations of old industrial/housing areas and the regional agricultural landscape associated with the constraints on the expansion of the built-up area to accommodate economic and population growth. These areas possess specific spatial conditions for long term economic development. At the same time, they are usually located on the newly reclaimed land at the estuaries of the delta, with dense waterways, vast areas of fishing ponds, wetlands and agriculture with highly sensitive ecosystems and are very vulnerable to flooding. In this phase the possibilities for the development of regional green-blue infrastructures and city-level water networks are identified for increasing adaptive capacities, ecosystem services and water safety.

5.1 Scenario Studies

To investigate the PRD’s likely future development, scenario studies are employed.In scenario studies realism and imagination are combined to identify critical key locations, driving forces and prospective impacts of occurrences in the future — both opportunities and threats(Fig. 11)[1]293-312. Using scenarios is an useful instrument to address uncertainty and to generate understanding about trends and their relationships,new challenges and policies, and their effects. It also structures strategic discussions and encourages involvement of various stakeholders[57],[58]11-13. For now the scenarios are conducted in an academic setting, but with involvement of governmental authorities and water boards. Building scenarios involves formulating an internally consistent and coherent set of hypotheses on the primary relationships that are explored. On the basis of these assumptions, a systematic but selective description of the current scenario can be made,as well as identifying the most significant external variables that determine the course of spatial development[56]11-13.

5.2 Developing a Regional Strategic Vision

Together with the assessment of urban landscape growth over time and the evaluation of present spatial development projects in the region,several significant factors of future development are identified which led to an initial strategic vision for the PRD. The vision needs further elaboration on the basic idea that the PRD will develop into China’s Silicon Valley with strong developed and well connected urban qualities, robust greenblue frameworks, have cultural-historical assets connected to the region and water sensitive socioecological inclusive urbanism. According to the initial idea the East-wing (Guangzhou-Hong Kong corridor), the PRD will further develop into a well-connected red-green necklace, with strong urban hubs and marinas, alternated with robust green corridors that connect the mountains to the sea. The West-wing will take benefits from the wet plains developing into a blue axis with water sensitive ecological agri-aquaculture and flood storage, complemented with strong urban hubs that benefit from transit oriented development (TOD).

5.3 Transformation Perspectives

The primary use of the regional strategic vision is to determine priorities in spatial planning and design.Back casting is used to identify spatial transformation perspectives that help to accomplish the objectives as set by the strategic plan and guide actions according to. The spatial transformation perspectives provide a set of adaptive design strategies that are specific to the challenges and potentials of the territories in the subdeltas and the estuary of the PRD. The perspective of each transformation has a spatial dimension and is: water sensitive and socio-ecologically inclusive,flexible and multifunctional and addresses multiple temporal and spatial scales. In the sub-deltas, the transformation perspectives are connected to the river and rain water adaptive approaches and which includes design principles for resilient river design, integrated agri-aquaculture, sustainable urban transformations,new urban districts, integration of (historic) villages,industrial transformation and eco-tourism. In the estuary, the transformation perspectives are mainly connected to sea water adaptive approaches which includes design principles for multifunctional flood protection, harbour and marina development, land reclamation (sedimentation, erosion), development and transformation waterfronts and protection and development of mangroves and other coastal ecosystems.

Each of these transformation perspectives need to be elaborated into more detail. Design principles need to be identified by studying relevant and successful (international) cases. In addition,their potential needs to be explored through a research through design process. Strategic areas can serve as experimentation sites, to test the possibilities of their application in a spatial and visual way. In Sun Chuanzhi’s paper readers can find further elaboration on agri-aquaculture for multiscale water-sensitive design in the PRD[59].

5.4 Action Outlook

In order to put the gained knowledge and ideas into action, it is important to address the question of whether it is possible to create conditions for new governance arrangements. Therefore the regional design involves speculation in order to investigate if and how different stakeholders would be able to find ways of collaborating, agreeing on a design and fine-tuning it. As discussed, the regional design process must facilitate an understanding of urban landscape dynamics and the transformations through an ex-post evaluation of existing urban planning strategies and projects, and an ex-ante evaluation of scenarios of potential adaptation strategies[5]3-4. Communication is a central issue and it is crucial to develop and utilise innovative visualisation methods and tools that permit the involvement of local stakeholders and decision makers. Throughout the process, interviews and workshops with stakeholders are organized to investigate possible agreements between them.During the workshops, stakeholders are brought together around digital map-tables (Fig. 12),where the relationships between different systems can be shown. Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality are also other mediums that are employed[60]. Participants are able to see the possible consequences of their initiatives on other systems.These innovative visualisation methods speed up the discussion on different proposals with all the stakeholders and will form the basis for the further development of the regional vision and related strategy. The transformation perspectives that will guide the development of the delta towards a more sustainable future.

6 Conclusion

As discussed, the PRD’s urban landscape is the result of various processes and systems that have different dynamics of change and influence each other. The ability to interrelate systems through spatial design has become increasingly important,as the interconnection of different systems and their formal expression is a fundamental aspect of contemporary regional development.

Landscape-based regional design is put forward as an inclusive planning and design approach for adaptive transformation of the PRD.The paper outlined an approach rather than the outcomes. In times of complex challenges the development of approaches like offer alternative ways of understanding, socio-ecological inclusive design processes and modes for collaboration amongst disciplines and stakeholders. Landscapebased regional design stimulates design disciplines like architecture, urban planning and landscape architecture to cooperate. It also reviews the agency of spatial design by giving shape to the built environment. In addition, as an inclusive design approach it establishes relationships between ecology and cultural aspects, process and form,long-term and short-term developments, and regional strategies and local interventions. As such landscape-based regional design is a powerful vehicle for guiding territorial transformations in a process of creating local identity and safeguarding regional relationships, and at the same time linking ecological and social processes and urban forms.

In this line of thinking, landscape-based regional design provides a new operational power for spatial design — as an integrative, creative activity— and recognizes the regional urban landscape as a significant field of inquiry that is context-driven,solution-focused, and transdisciplinary.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Dr. Gregory Bracken for English editing.

Sources of Figures:

Fig. 1 © Xie Guangyuan; Fig. 2 © Steffen Nijhuis based on SRTM (30m), Hydropolis; Fig. 3 © reference [37]; Fig.4, 11, 12 © Steffen Nijhuis; Fig. 5,8 © reference [50]; Fig.6,7,9,10 © Steffen Nijhuis, Daniele Cannatella & Xiong Liang, the statistics from SRTM (30m), Hydropolis, google map, baidu map, OpenStreetMap (OSM, 2018.4), land use data from Word ecology land unit (250m, WorldELU, 2015),Globeland30 (2010), port data from the World Port Index Database (WPI, 2018.4), old town data from reference [50].