公众健康和幸福感考量的城市蓝色空间

——城市景观研究新领域

2019-12-02西蒙贝尔陈奕言陈筝

著:(英)西蒙·贝尔 译:陈奕言 校:陈筝

在可被视为构成区域景观系统环境的所有方面中,水文系统无疑是关键要素之一。 所有的景观,甚至沙漠,都可以被分解成一个个汇水盆地(hydrological basins),这些汇水盆地是可持续评估绝佳的分析单位,因为它们在许多方面都是独立的景观单元。流域(watershed,美国使用)或河流汇水区(river catchments,英国使用)跨越了多个尺度,一个个小的汇水区组合成更大的汇水区,形成了嵌套的分形(fractal)结构[1]。侵蚀和沉积的持续地质过程以及河岸生态过程有助于流域形成一种蜿蜒分支又不断变化的独特模式[1]。因此,在区域水文系统的上游地区发生的如泥沙沉积、森林砍伐或污染,会不可避免地向下游发展,并对下游地区的功能产生影响。同时,随着系统支流逐渐向某条河流通往的地点汇合,这些支流会集中到一起。

如果我们回顾全球人类聚居的历史,可以看到绝大多数聚居地和城市都位于水域——包括临江临海的港口城市、河流交汇的要塞居民点、因水利发展起来的工业城镇群、渔村、海滨度假区等[2]。从最初在美索不达米亚(两河流域)、尼罗河流域、黄河和印度河流域的城镇雏形开始,河流沿岸不仅聚集了村落和城市,而且也因河建设了一系列包括灌溉系统、运河和港口等航运水利工程。为方便运输和控制洪水,现代城市进一步建立了大量的河流调节系统,使城市建设得以突破自然洪泛区的限制发展,但同时也增大了因上游汇水区管理不善引起的灾害风险。可见,人类对河流汇水区的利用和滥用给人类和生态健康都造成了严重困扰。

纵观全球,每个大陆上的城市都在经历着规模、结构、人口密度和生活节奏的迅速变化。沿海城市人口在不断扩大[3],这些城市往往把水岸当作消极空间并限制其可达性。然而在过去20~30年中,许多这样的城市被重新开发,水资源成为人们旅游和休闲娱乐、商业和新住宅开发的主要吸引力。这些重新开发包括港口设施(被远离市中心的集装箱港口所取代)、河滨地区(综合考虑洪水管理和自然软化岸线成为新主流)以及全球贸易格局变化后的其他类型滨水空间[4]。尽管滨水再生(waterside regeneration)带来的生态、社会和经济影响已得到一定关注[5-6],但它对公众健康和幸福感的潜在影响直到最近才开始有一些科学研究[7]。蓝色空间健康价值研究的滞后和城市绿地(如城市公园、林地和行道树等)在保健和疾病预防方面的大量实证形成了鲜明对比[8]。20世纪和21世纪初,世界各地沿海地区城市化和人口均呈现出增长趋势,研究表明这种增长趋势很可能持续下去[3]。因此,随着越来越多的人发现自己工作和休闲娱乐时都在直接或间接地与城市水域接触,“蓝色基础设施”(blue infrastructure,水体及其临近滨水空间)开始在城市规划和景观设计中发挥越来越重要的作用。

近几十年来,人们对与水相关的健康危害和风险有了更全面的科学认知。其中一类风险是人类通过水可能会接触到导致传染病(如霍乱、伤寒等)的微生物[9]、一系列化学污染物,在某些特定的水生生境中,还可能因接触到疟疾、黄热病和登革热等疾病的媒介而患病。而水本身也是一个重大的风险,溺水是全球第三大最常见的意外死亡原因[10]。同时,洪水也是部分地区的主要灾害之一,该问题因洪泛区建设和透水地面硬化的增加而进一步恶化,为洪水消退后埋下健康隐患[11]。此外,在蓝色空间(水中或海滩上)进行的许多娱乐活动也带来了与水无关的健康影响,如增加了晒伤和患皮肤癌的风险等。环境退化、城市微气候(城市热岛)和极端天气(如热浪)等进一步放大了上述风险。然而,蓝色空间及其基础设施所带来的公共健康福祉和个人幸福感提升,我们却知之甚少。

那么,居住在水域附近或使用水域进行娱乐活动对健康有哪些益处?越来越多的流行病学证据表明,在海岸附近或有海景可观的居民通常更加健康,有更少的精神损害(mental distress)症状,并且比内陆居民对生活更加满意[12]。长期证据显示,在海边生活或曾在海边生活的人们的身心健康状况通常可能更好[13]。这些影响是否仅限于海滨环境,河流、湖泊、运河等其他蓝色空间是否有类似的健康效益,目前尚不清楚。

蓝色空间如何有助于改善大众健康和幸福感?早期证据表明,某些影响机制或可解释接触蓝色空间与公众健康之间的积极关系。首先,研究指出蓝色空间环境较其他户外场所,更容易让人们感到快乐,压力更小[14]。其次,丹麦的一项研究发现,附近居民在蓝色空间停留的时间通常比住得较远的市民长[15]。再者,英国的一项研究表明,海岸附近居民似乎比内陆居民更符合英国国家体育活动指导方针中身体素质的相关要求[16];而另一项英国研究表明,蓝色空间被视为与朋友和家人进行积极社交活动的重要场所之一[17],与绿色空间相比,蓝色空间更广泛地用于改善公众健康和提升幸福感[18]。最后,水体的比热容较高,更有助于缓解局部城市热岛效应。如果对夏季气温及热相关疾病的发病(死亡率)上升的预测准确的话,这一作用可能今后会越来越重要[19]。

当前城市呈现多元发展趋势,其中全球面临的一个主要问题是城市蔓延(urban sprawl):低密度城市化占用了大面积的绿地[20]。为了应对这类问题,越来越提倡城市紧凑发展,尤其是棕地置换[21]。这同时也给城市绿地带来了压力,如果不加以保护,这些绿地的数量和面积将会减少,质量会降低。 虽然一方面城市不断地在填海造陆拓展开发空间,但随着滨水城市的人口不断增加,城市蓝色空间将会成为越来越重要的生活和娱乐场所。因此,在城市规划和城市基础设施规划建设中综合考虑蓝色空间的健康实证效益,可有助于解决现今公共健康面临的关键挑战,包括减少与生活压力、久坐的生活方式相关的非传染性疾病的发病率,降低与温度升高相关疾病的发病率和死亡率等[22]。

目前对蓝色空间健康效益的研究远不如对绿色空间的研究成熟[23],对海岸线以外其他蓝色空间的研究尤为薄弱。欧洲只有少数几个国家进行了研究,并且由于统计功效(statistical power)偏低的缘故,结论统计上并不显著,在世界其他地区的研究进展也类似[24]。因此,对蓝色空间在预防不良生活方式引发的疾病、改善人类健康和幸福感方面的潜在作用亟待深入研究。“蓝色健康研究项目”①的首要目标就是填补这方面研究的空白。从2016年启动到2020年截止,这个泛欧洲项目旨在更深入地研究接触蓝色空间与公众健康和幸福感之间的关系,通过大规模、系统的跨学科研究,调查在欧洲不同的地理、气候、社会经济和文化背景下 ,接触蓝色空间对健康和幸福感的影响。本研究的一个重要目的在于改善城市蓝色空间的规划和设计,以帮助规划者最大限度地提高效益、降低风险。有关项目和所用研究协议的概述,可以进一步查阅Grellier等人的相关研究[25]。

本研究旨在介绍蓝色健康项目部分工作的初步成果,尤其是关于如何评价城市蓝色空间规划设计质量和有效性的问题。这里总结并评价了一系列全球范围内已实施的项目,这些项目通常位于曾经的工业区,目标是重新开发蓝色空间并增加娱乐休闲的功能和发挥有益健康的潜力。由于“蓝色健康研究项目”还没有结束,所有的调查结果尚未得到充分的分析和讨论,在这里仅对现有进展进行概述。笔者之所以在此次“区域景观系统”(regional landscape system)主题会议②中向大家介绍蓝色健康项目,是因为这可能是个极其重要的研究领域,应当被纳入针对水文功能恢复的政策、计划或实践系统中;通过使用可持续的城市排水规划或者中国的海绵城市战略[26]来降低城市洪水风险,以实现蓝绿基础设施、基于自然的解决方案(nature-based solutions )③和其他专题城市规划概念等综合需求。本研究将以案例的形式,介绍项目评议(project review)的概念并总结其主要成果。

1 项目评议的概念

项目评议即系统地对项目投入使用的现状进行考察评议,项目评议并不像常规科研论文那么常见,但从科学的角度来看并非没有先例。使用后评价(post-occupancy evaluations)在建筑和风景园林行业已经越来越普遍,但通常是针对单个场地或建筑,而非对多个项目进行评估对比。评价(自然或社会)科学发表的同行评议学术论文相对比较容易,因为其质量(在同行评议审核其能否发表的过程中)得到了控制。那么在考察风景园林项目时,有没有类似的等效程序?文学评论在艺术和设计学科中起到了类似同行评议的作用,在风景园林学科中也是如此。

最近有一些出版物(主要是书籍)从不同角度对特定类型的蓝色空间进行了研究和评述[27-30]。虽然其中包括了一些优秀案例,但它们都没有从改善大众健康和幸福感的角度论证。笔者首次尝试对广泛的项目类型进行更为全面和综合的总结评议。

2 项目挑选方法

纳入评议的项目采用以下标准进行挑选,(在第一轮挑选时)这些标准相对宽泛而包容,而非严格限制[31]。

1)规划和设计项目应在城市范围内(可以包括城市边缘的农村地区),并为公众提供达到和使用各种类型各种规模水体的机会。

2)项目不受国家或地区限制,但须主要是在近10~15年内建成(不过也包括了一些建成时间更长的项目,因为它们被期刊批判性地重新审视,并提供了更长远视角的经验教训)。

3)项目满足以下条件中的一点或多点:①曾在学界普遍认可的专业期刊上发表;②曾在竞赛中胜出;③曾获专业组织颁发的奖项;④曾被作为高质量设计项目在网站列出并获得高度评价。

4)鉴于大多数项目不可能进行实地考察,应当有足够的资料可供评估(部分项目小组成员有实地考察过,且/或非常著名)。

5)通过卫星图像搜索引擎,特别是谷歌地球(GoogleEarth,尤其是其中的街景功能),可以看到项目的现状和项目刚建成及使用后的状况(以避免设计师提供的完美照片影响项目给人的客观印象)。

表1是用于确定纳入评议项目的主要期刊和网站、它们的出版商、所属国家和报道重点。最初发现了近400个潜在项目,随后减少到172个最具代表性的,作为本评议的实证数据库。完整的项目集合会在之后整理成一个可供查询的数据库,在此不再单列。

3 评议考察方法

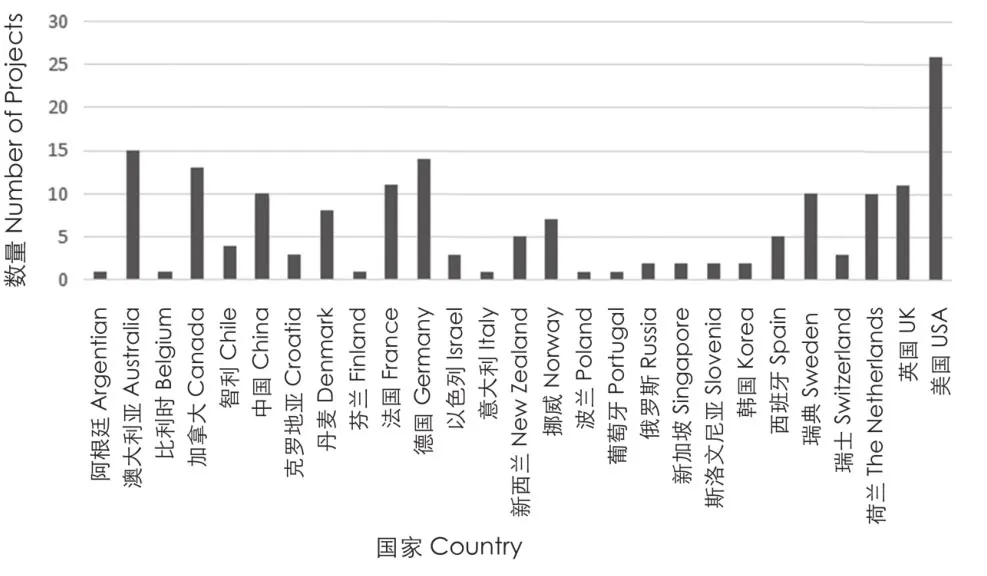

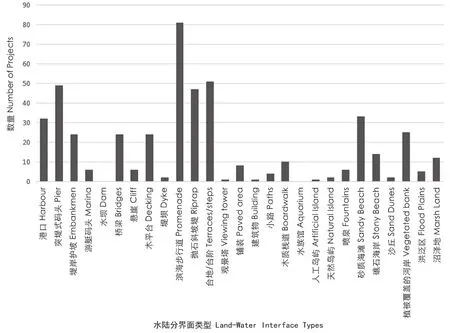

评议考察的分析方法包括定性和定量两种。通过阅读各个竞赛和奖项的评审委员会给予这些项目的评论和评语、颁奖词、相关文章和论文以及在线评论网站上的评论,可以了解到业内对这些项目的评价。研究人员(爱沙尼亚生命科学大学风景园林系主任下属有风景园林资质的员工)对上述内容进行了检索,并使用谷歌地球及其街景功能对项目进行了考察。在对项目进行专题分析时,将一些现有的评价标准,例如绿旗奖(the Green Flag Awards)④、公共空间计划(Project for Public Space, 简称PPS)⑤、空间塑造(SpaceShaper)设计委员会⑥等进行整合,从而形成了本研究项目考察和评议的标准体系。从评议的项目中提炼出若干专题,并针对这些专题对每个项目进行比较,形成一份定性的总结报告。笔者也将主要围绕介绍这份定性的总结。定量研究详细的研究方法及结果将在分析完成后另行介绍。图1~3展示了调查项目的基本特征——所在国家/地区、蓝色空间类型以及水陆界面的类型。

4 分析和结果

4.1 总体设计层面

决定项目是否出色、是否更具审美吸引力的因素主要包括:对水和水陆分界面的理解;如何将水这一元素融入设计中去;设计(包括设计元素和材料)对当地周边环境的适宜性和可供性(affordability)等。此外,设计的创新性和可持续性也是评判的重要因素。每一个被考察评议的项目都有某种或某一系列的具体特征,构成该项目的独特性,例如对场地曾经用途的考虑(例如过去的港口),并将相应元素纳入设计中去(例如起重机、铁路轨道、系船柱及其他要素)。除此以外,一个有力的、大胆的焦点特征(尽管有例子采用艺术品形式,但并不限于此)也可以给予场地新的定义和令人印象深刻的形象(这也有助于建立品牌),从而创造出一个新的场所。

许多项目将水作为创造或恢复地域特色的一种手段,例如设计师在设计中运用创造性的设计方法将陆地与水在空间上或视觉上联系起来,从而最大限度地提高审美感受和感官影响;或是运用设计来弱化城市背景,使人们的注意力聚焦到水体上。

我们也可以看到,在形式、颜色、材料和纹理的使用上,许多项目呈现某种特定的当代“外观”。这是因为设计师们在寻找先例进行借鉴的时候,一些特定的风格不可避免地会影响他们的设计,甚至在设计师们试图表现个人主义和独特性的时候也是如此。

值得注意的是,相比绿色空间项目,蓝色空间项目为了满足滨水区更高的建设要求,常常会有更独特的解决方案。比如蓝色空间的构筑物往往从美学和结构工程角度综合考虑,以发挥水岸防护和亲水活动的双重作用。

表1 用于挑选和确定需要考察评议项目的专业杂志和网站Tab. 1 Selected professional magazines and websites used for sourcing projects to be reviewed

1 评议项目所在的国家Countries where reviewed projects are located

较大的场地通常被细分为不同的功能区和景观区。有些设计师把正式(如各种体育活动)与非正式的活动分开设置,或根据不同类型的儿童游戏、植被或水进行分区。这种分区通过提供不同审美体验或不同生境以提升场地的吸引力和趣味性,通过视觉上的空间分隔创造空间层次、减少拥挤感。

4.2 促进身心健康和幸福感的潜力

除了一些非常小的设计(如水景),所有滨水场地都可以促进体力活动,即使仅限于陆上运动。其中最主要的是散步和慢跑,器械运动以及其他正式或非正式的运动也非常普遍。

这些场所基本都设计得很好,人们可以在其中欣赏风景、独自静坐、沉思,等等。但由于临水区域往往很受欢迎,除了一天中的特定时刻,很难找到可以在滨水区独处的机会。如果在稍微大一些的项目中想找可以独处的地方,需要避开滨水区,比如紧邻水岸的植被区域。

大多数场地具有明显的城市化特征,因此很难不考虑城市环境及其视觉影响。比起开阔水面,即使观赏者背对城市,可能城市环境也会削弱滨水空间的压力缓解效果。

4.3 可达性和无障碍设计

在绝大多数情况下,场地可以很容易通过步行、骑自行车或公共交通到达。由于项目场地提供了停车场,即使在市中心地区自驾车也可以方便地到达。与德国或中国相比,美国和澳大利亚因其对于汽车依赖性更大,它们的项目场地通常都配置了停车场。

在极少数的情况下,设计师会考虑让人们从水域进入到场地。有些案例游客可以通过客轮到达新公园旁边的码头;另一些案例游客可通过游船经小型码头停靠进入。

大多数项目场地都有考虑无障碍设计——即使在地形相当陡峭的情况下,也设置了带坡道的台阶提供亲水机会。只有不多的几个例子,由于条件实在不允许而没有进行无障碍设计,但这显然是极少数。在并非十分狭窄的长条形场地内,内部的无障碍联系就非常重要——通过这种联系将场地内不同区域联系起来,并串联起其他各种各样的小路。

2 评议项目涉及的蓝色空间类型Blue space types associated with the reviewed projects

3 评议项目中涉及的水陆分界面类型The types of water/land interface encountered in the reviewed projects

一般情况下,尽管场地内基本都可以骑自行车,但许多场地存在或可能存在自行车停车位不足的问题。这取决于不同国家的自行车骑行文化,荷兰和丹麦在这一问题上处理得较好。

海滨和湖岸区域开发的时候往往都将滨水直接可达性作为重要考虑之一。大部分项目考虑提高可达性,尤其是老年人和残疾人的可达性,并为生态敏感地区设置对生态系统更安全、更小破坏的游览路径。城市中心河流和码头的设计难度更大,设计师往往会提供通过视觉及其他感官的间接亲水体验,但出于水文或水质考虑没有提供让人们直接进入水的机会。同样的考虑,也常见于公园中结合水处理工艺的植被过滤系统。人们虽然不能直接接触水,但所有其他体验都非常好,也能看到水生栖息地及相应的野生动物(图4)。

有一些项目的坡道和台阶的设计非常有特点,通过独特的设计形式融入到场地整体审美体验中,成为项目的核心。除了坡道和台阶,扶手在人们使用台阶和坡道时也十分必要——如果有老年人经常使用,有没有扶手会有很大的不同。

从一个地点到另一个地点的路径联系也非常重要,例如曼哈顿的前码头(former docks of Manhattan),设置了多条人行道将一系列独立的小公园联系起来形成一个公园系统。此外,沿海景观步道、长步行道以及滨河步道都有助于连接不同的区域,给人们提供更系统的游憩体验。

因此可以总结出上述项目成功的关键点之一是它们都拥有一个经过深思熟虑的可达性和无障碍设计策略。要做到这些,不仅要考虑场地本身的规划设计,还要考虑人们如何到达。这也要求设计师与负责交通运输、道路管理的机构紧密合作,有时还需要和管理铁路、地铁以及港口的机构合作。能否步行、能否骑车、场地周围街道和十字路口的分布情况等,以及公交车站、地铁站和停车场的位置和步行距离,都需要设计者仔细进行考虑。

4.4 与水的互动

被考察的所有项目的另一个关键是都最大限度地挖掘与水互动的潜力。虽然一些项目出于实际或安全的考虑不让人们直接接触水,但所有项目都非常重视视觉和其他感官等与水产生互动的方式,有些处理得非常具有创造性。

一些项目的场地靠近堤防和运河或码头,所以人们不可能直接接触到水。但它们很巧妙地在临近的码头或堤岸上设置了水景,创造了人们与喷泉的互动机会——孩子和成人都把在炎热的天气里被喷泉淋湿甚至淋透当作一种享受。另一些项目的场地虽不靠近自然水体,但喷泉或其他水景设施的吸引力如此之强,致使它们成为新公园或城市广场的焦点。这在一定程度上是由于作为流体的水有着运动变化的特质——喷射、薄雾、镜面、急流、冲击波、潮汐等,造成灵动的水与静止的地面形成了鲜明的对比。

在有码头垂直护岸或防洪堤的场地,滨水区往往高于水体。在很多项目中,如何使人们能够下来亲水是设计的关键。这可通过设计在洪水期间漂浮或淹没的亲水设施实现。也可以将船只捆绑在较低的梯田或码头上,这些措施可以在水质较差的滨水区增加亲水和水上游憩活动(图5)。

如果想和水更亲近些,还可以通过可坐的码头或驳岸,这类手法可结合到河流自然化项目中。这类河流可能非常湍急,但即便有一点危险,靠近水面也能给人带来一种特殊的体验——一种壮美的体验,这可能帮助人们从城市环境中脱离出来,从而实现精神恢复。

4 中国哈尔滨的群力雨洪公园,是俞孔坚和北京土人景观规划设计研究院设计的一个城市湿地公园获奖范例。公园由于雨洪管理和生态保护等原因,对可达性进行了限制。公园具有独特的现代构图,为一个人口密集的城市提供了接触自然的多重可能Qun Li Stormwater Wetland Park in Harbin, China, a prizewinning example by Yu Kongjian and Turenscape of an urban wetland forming a park, although with limited access to the interior of the territory due hydrological purposes. It has a distinct contemporary look and many possibilities for getting close to nature in a densely built up city

无论是在海边还是湖边,人们都很喜欢与水的互动。许多项目都会考虑海滩和海滨设施的修复,甚至包括填沙和使用结构物防止海滩沙子流失。此外,很多项目也会重视植被修复。这说明,虽然设法使人亲水仍然是设计的重点,但构筑物在调节人与水岸空间之间的互动中也发挥着重要作用。

4.5 座位和社交机会

所有被考察的项目都特别注意座椅的设置。一些场地配备了大量的标准长椅,这些长椅看上去使用频率很高。在有些项目中野餐和烧烤活动很受欢迎,通常这些区域会设置餐桌,在喜欢烧烤的地方餐桌旁往往还会有烧烤架。长椅可以采购现成的商业成品(价格经济、易维护等),也可以为项目定制。

还有一种常见的形式是将座椅以一种更基本的设计元素嵌入到设计中——就是用露台、台阶和低墙作为灵活的多用途构筑物,它们维护要求低,同时避免了过多设施带来的杂乱,使场地显得更加简洁。

一些有潮汐的温暖海域项目,设置了通向水中的台阶,可以在潮汐中提供半在水中、半在水外的座位,这对于老年人或残疾人来说是非常理想的,他们可以享受在水中浮动的感觉。水面上的漂浮座位也可以提供类似将脚浸入水中的体验,不同的是这些座位能够随水位的变化而变化。

另一种受欢迎的座位类型是固定的或可移动的日光浴床,它们有斜面可供坐、躺、斜倚等不同使用方式。它们在内陆的人工“海滩”尤其受欢迎,这些“海滩”为城市居民提供日光浴的机会。它们还可以用于那些没有沙滩或沙滩存在侵蚀问题的礁石海岸。

4.6 改善小气候

滨水地区经常暴露在强烈的阳光、狂风暴雨或冰冻的环境条件下。如何让它们在一年四季都能被舒适地使用,存在一定难度。由于市区内的许多场地缺乏植被或只有有限的植被(如以前的港口和工业区),这些地点往往特别容易受到自然因素的影响,由于土壤缺乏和排水不良,树木较难成活。无论是易于还是不易于植物成活的场地,乔木和灌木都需要一段时间才能长到能够提供良好遮阴的冠径,因此即使是一些以种植为特色的项目,也会使用构筑物来代替树木。

很多成功项目都会考虑场地的微气候——当然,在不同的地方有不同的解决方案。很明显,许多场地在这方面进行了大量的思考和创新。晴雨伞、可以收放的顶篷、带攀缘植物的廊架,以及紧密间隔的树苗(为了获得即时效果)都是很好的解决策略。

对于现状植被良好的地方,设计师需要在设计中尽量保留这些植被并且考虑到后期的养护管理,同时长期不断地丰富植被。由于盐、风、石质土等原因,海滨地区不利于树木和其他木本植物的生长,因此选择合适的植物品种来进行配置可能不像普通公园那么简单。

还需要注意利用临时设施来夏季遮阳、冬季避寒,有时一个临时设施可以兼具上述双重功能,比如一些项目中采用的棚架。

4.7 场地管理和维护

几乎对所有考察过的项目来说,良好的场地管理和维护十分重要。场地中几乎没有任何地方有损坏、故意破坏或植被破败的迹象,所有的垃圾箱都配备齐全,同时得到了良好的使用,并有定期的垃圾收集。

在很多项目中,充分考虑材料的设计、使用以及施工质量,可以更好地提高管理和维护环节的性价比。这类设计往往比较简洁,使用标准化元素构件,如果需要可以很轻松地对其进行维修或更换。

良好的维护告诉使用者场地被精心管理着,这也意味着该场地是安全的,欢迎使用。损坏和破坏行为通常更有可能发生在衰败的社区和那些晚上较少有人使用的地方(或晚上有反社会活动的地方)。在我们考察的项目中,很少出现这类问题。

4.8 安全感和安全性

与水相关的安全问题显然十分重要。在美国的项目中,沿着水岸边缘一般都会设置栏杆,但在其他国家很少设计这样的栏杆,理论上来说人会有落水的风险。这意味着设计师必须寻找一个合适的风险平衡。

大部分项目极少配置救生圈、救生员、救生船等水上安全设备,即使那些设置了海上游泳活动的项目也是如此。可能只是我们没有找到证据,但大量照片显示在盛夏的场地上也很少有或几乎没有提供上述水上安全设备。

人身安全(如犯罪)并非主要问题。现在设计师知道通过改善夜间照明,减少可能发生反社会或违法活动的场地,增加人群使用实现场所监督等设计手段使场地变得更加安全(图6)。

大多数场地都有良好的后勤通道,便于维修、也便于救护车或其他应急车辆通行,确保了任何事故发生后都能够被迅速处理。

4.9 食品销售和餐饮机会

在所有的场地,游客通常都愿意花时间吃点心。野餐既可以是非正式的,也可以用桌子,在烧烤更受欢迎的地方可以考虑设置较多的烧烤架——这需要结合当地文化习惯。很多地方也可以通过餐饮来吸引游客,如设置冰激凌摊、大型的餐厅、酒吧和咖啡馆等。

5 讨论和结论

从上面的分析可以看出,自20世纪80年代以来,在去工业化、新港口技术开发后,以及随着人们对于雨洪管理的日益关注,针对滨水开发和无障碍水上项目的考虑越来越多,现已成为风景园林和城市设计实践的主要组成部分。规划者和设计师清楚地意识到,有必要使这些地方具有吸引力、标志性和可达性,也需要考虑它们的无障碍、安全性、易于维护,并在实际和其他限制条件下,提供尽可能多与水的接触机会。笔者考察的所有项目都旨在通过提供体育活动、社交、放松、亲近自然、沐浴阳光和减压的机会,促进身心健康并提升幸福感。此外,可以清楚地看出,绝大多数的项目都被很好地使用,无论它们位于哪里。在绿色空间很少的密集城市中,蓝色空间提供了一个补充性的或者说替代性的环境。

当然,这项研究也有局限性。虽然研究样本量大(172个),但这只代表了能找到的最受好评或关注的项目。那些在出版物或网站上看不到信息的项目,则不可能纳入本次考察评议。此外,同行评议过程主要由其他风景园林师进行,他们也许不会评估可能对项目产生负面影响的因素,如生态破坏等。同时研究人员无法亲自视察绝大部分项目,这意味着许多与场地相关的细节可能被忽略。但采用谷歌地球和谷歌街景等工具,采用游客上传的照片、“大数据”以及社交媒体开源数据等新型数据形式来开展研究,将变得越来越普遍。这些手段提供了在今后一段时间进一步考察评估项目的可能,这是一个令人振奋的研究机会,尤其对于风景园林类项目。因为它们往往需要一定时间去成长和发展达到最佳状态,所以时间对评价非常重要。

项目的设计者在进行规划设计时,可能会考虑到大众的健康和幸福感,也可能不会。然而,在这些备受赞誉的项目中,可以清楚地看到,哪些主要因素已被纳入其中,哪些研究已确定为对促进健康和幸福感的重要因素。因此,本研究涉及的这种在项目投入使用后再进行评价的尝试已经揭示了一些关键点,它们可以成为规划者和设计师的指导方针,无须在其他地方再做进一步深入的分析。

综上,可以认为,城市蓝色空间有可能在促进城市居民的健康和幸福感方面发挥着重要作用。同时,作为河流、湖泊和海洋等区域景观系统的一部分,城市规划者和设计师应当考虑对城市蓝色空间进行更多的研究并加以合理利用。

(本文以作者在2018世界风景园林师高峰讲坛上的发言稿为基础进行补充。)

致谢:

感谢同事们,特别感谢Himansu Sekhar Mishra,在选择和评估本研究所涉及的项目时所提供的帮助。

注释(Notes):

①www.bluehealth2020.eu.

② 译者注:此处指的是2018年9月22—23日在北京举办的世界风景园林师高峰讲坛的主题。

③ IUCN Nature based solutions(www.iucn.org/commissions/commission-ecosystem-management/our-work/nature-basedsolutions最后访问日期为2019年3月30日)。

④ http://www.greenflagaward.org.uk/ 最后访问日期为2019年3月30日。

⑤ www.pps.org/最后访问日期为2019年3月30日。

⑥ www.designcouncil.org.uk/resources/guide/spaceshaperusers-guide最后访问日期为2019年3月30日。

图表来源:

图1~3 © Himansu Sekhar Mishra;图4、6 © 西蒙·贝尔;图5通过Creative Commons授权使用;表1由Himansu Sekhar Mishra整理。

Of all the aspects of the environment which can be considered as comprising a regional landscape system, surely that of the hydrological system is one of if not the key element. All landscapes — even deserts — can be broken down into hydrological basins and these make excellent units for assessing sustainability since in many ways they make separate and discrete landscape units.Watersheds (American usage) or river catchments(English usage) occur at ranges of scales, with smaller catchments forming sub-sections of larger ones and so on in a fractal structure[1].The continuing geological processes of erosion and deposition as well as the riparian ecological processes contribute to the formation of a distinct pattern of meanders and branches which remain dynamic[1]. As a result, what happens upriver in the higher parts of a regional system — such as sediment capture, deforestation or pollution — inevitably works its way downstream and has consequences for functions along the lower reaches and, as the tributaries of a system gradually combine towards the point where a single river results, these may be concentrated.

If we look at the history of human settlement globally and, in particular, the location of cities,we can see that the vast majority are located on water — harbour and port cities on river sea or lake coasts, bridging and defensive points, industrial concentrations using water power, fishing villages and towns, seaside holiday resorts and so on[2].From the earliest times of city development in Mesopotamia, the Nile valley, the Yellow River or the Indus valley, for example, not only have settlements and cities been located on rivers but the rivers and hydrological systems have been modified and engineered with irrigation systems, transport canals, dams and excavated harbours. Extensive river regulation systems to facilitate transport and to try to control flooding have been more recent features, enabling cities to expand onto flood plains and as a result to render them prone to extreme events exacerbated by upstream catchment mismanagement. Human use and misuse of river catchments has also caused major problems for human as well as ecological wellbeing.

All around the world, on every continent, cities are experiencing rapid changes in extent, structure,population density and pace of life. Populations of coastal cities are expanding[3]and many such cities, which often turned their backs on the water and restricted access to it, have, over the last 20-30 years, been extensively redeveloped and the water has become a major attractor for tourism and recreational use as well as for new residential development and business. This includes port facilities (as container harbours have taken over and moved out from city centres), riversides — where new approaches at flood management and re-naturalisation have become trends — and other types of waterfront,following changes in global trading patterns[4].While the environmental, social and economic implications of waterside regeneration have received some research attention (e.g., Jones[5], 1998 or, more recently Sairinen and Kumpalainen[6], 2006), the possible impact of this activity on public health and well-being have only recently seen scientific investigation (eg., Völker and Kistemann[7], 2011).This contrasts with the extensive evidence base for the role of urban green spaces (such as urban parks,woodlands and street trees), in health protection and disease prevention[8]. The trends in urbanisation and population growth seen over the 20th and early 21st centuries in coastal areas around the world are forecast to continue[3]. Therefore, as more and more people find themselves in direct or indirect contact with urban water spaces through work and recreation, “blue infrastructure” — the waterbodies and their associated terrestrial margins which often provide the access to the water — starts to play an increasingly important role within urban planning and landscape design.

The scientific understanding of a range of health hazards and risks associated with water has been well-developed over several decades. One class of risks relate to sources of human exposure to microbes responsible for infectious diseases like cholera and typhoid[9], to a range of chemical pollutants and in the case of certain aquatic habitats the support of vectors of diseases like malaria,yellow fever and dengue. Water itself is also a significant hazard, drowning being the third most common global cause of unintentional death[10]. Flooding, too, is a major hazard in some areas (and getting worse in part because of increased construction in flood plains and increased surface sealing) leading to a range of health risks following flooding (eg. Alderman et al.[11], 2012). In addition, many recreational activities taking place in blue spaces (in the water or on beaches) are associated with non-water-related health impacts, such as increased risk of sunburn and skin cancer. Many of these risks are amplified by the effects of environmental degradation and the urban micro-climate (urban heat island) and extremes of weather such as heatwaves. Far less is known about the public health and individual wellbeing benefits of interactions with blue spaces and infrastructures built in, on and around them.

What about the positive health benefits associated with living near or using water spaces for recreation?Increasing epidemiological evidence suggests that people living near — or having views of — the sea coast are generally healthier, experience fewer symptoms of mental distress and are more satisfied with their lives than those living inland (eg. Wheeler et al.[12], 2012). Longitudinal evidence supports the idea that physical and mental health are typically better in people who spend or spent time living near the sea[13].Little is known of the extent to which these effects are specific to coastal environments or whether similar benefits for health would be conferred by rivers, lakes,canals or other blue spaces.

How might blue space contribute to better health and well-being? Early evidence suggests several pathways which may account for the positive relationship between exposure to blue space and health and well-being. Firstly, several studies found that people feel happier and less stressed in blue space settings than in other outdoor locations[14].Secondly, a Danish study, found that people living near blue spaces typically spend more time there than those living further away from them[15]. Thirdly, in a UK study, people living near the coast seem to be more likely to meet national guidelines for physical activity than those inland[16]while another UK study showed that blue spaces are seen as particularly important places to spend time in positive social interactions with friends and family[17]and are more widely used for health and well-being purposes than green spaces (e.g. Barton et al.[18], 2016). Finally,water bodies, with their greater thermal mass, can contribute to moderating the urban heat island effect locally, which is expected to be increasingly important if forecasts of hotter summers and increased heat-related morbidity and mortality turn out to be true (e.g. Hajat et al.[19], 2014).

Trends in city growth take several forms.One main problem faced globally is that of urban sprawl which sees lower density urbanisation take up large areas of green land[20]. As a means to counteract this urban densification has been widely proposed, especially focusing on the redevelopment of brownfield sites (eg. Fatone et al.[21], 2012).However, this places pressures on urban green spaces which may be reduced in size and number as well as area and quality if not protected. While infilling of former harbours to make land for development still takes place, with populations near large water bodies increasing in size, urban blue spaces may become increasingly important sites for living and recreation. Thus, the incorporation of evidence on the salutogenic effects of certain exposures to blue spaces into urban planning and development of urban infrastructure has the potential to help to resolve key public health challenges, ranging from reducing the incidence of non-communicable diseases associated with sedentary lifestyles and stress to reducing morbidity and mortality related to increasing temperature[22].

Research on relationships between exposure to blue spaces and health is less well-established than that conducted on green spaces and health(e.g. Niewenhuisen et al.[23], 2014) and particularly for the effects of blue spaces other than coastlines.In Europe, research has been conducted in only a few countries and results have been inconclusive,largely due to low statistical power, while worldwide the same phenomenon is true (eg. Triguero-Mas et al.[24], 2015). Thus the time is right to conduct deeper research into the potential role of blue space in promoting human health and well-being and preventing lifestyle diseases. The overarching goal of the BlueHealth project①is to fill these gaps. Starting in 2016 and running until 2020,this pan-European project aims to understand better the associations between exposure to blue space and health and well-being through a largescale systematic programme of interdisciplinary research that investigates exposure to blue space and its effects on health and well-being in various geographical, climatic, socioeconomic and cultural contexts across Europe. A significant part of this research aims to improve planning and design of urban blue spaces so as to help planners to maximise the benefits and minimise the risks.For an overview of the project and the research protocols being used see Grellier et al. (2017)[25].

The aim of this paper is to present some preliminary results of part of the BlueHealth project work, in particular focusing on the question as to how to evaluate the quality and effectiveness of planning and design of urban blue spaces. Here a summary of a critical review of a sample of projects which have been implemented worldwide with the aim of redeveloping blue spaces, frequently former industrial areas, and increasing recreational and salutogenic potential is presented. As the BlueHealth project is not yet concluded and all results are yet to be fully analysed and conclusions to be drawn, this paper provides a kind of progress overview in this particular aspect. Its relevance to the theme of the “regional landscape system”②is to introduce this as a potentially extremely important field of research which needs to be incorporated within any policies,plans or practices which aim to restore hydrological functioning, to work on reducing urban flood risks through the use of sustainable urban drainage or, in China, the implementation of the Sponge City concept[26]and to address the combined needs of green and blue infrastructure, naturebased solutions③and other topical urban planning models. The overview will present the concept of the project review and a summary of its main outcomes, illustrated with a number of examples.

1 The Concept of the Project Review

A systematically-undertaken review of evidence from projects, as opposed to scientific articles, is an unusual but not unheard of activity(from a scientific perspective). Post-occupancy evaluations are becoming common in architecture and also in landscape architecture but these are usually of single sites or buildings, not a large selection of projects. While in sciences (natural or social) which publish results in peer-reviewed academic papers it is relatively easy to carry out a review since the evidence has been quality controlled(through the process of peer review) during the publication process, what is an equivalent system for reviewing landscape architecture projects? In the art and design disciplines it is the role of criticism to perform the equivalent of peer-review and in landscape architecture this is also the case.

There have been several recent publications —books mainly — which have examined and reviewed certain specific types of blue spaces from different perspectives (eg. Prominski et al.[27], 2012; Rottle and Yocom[28], 2011; Macdonald[29], 2013; Smith and Ferrari[30], 2012) but none through a health and well-being lens, although they also contain some excellent examples which were in some cases included in the review. This is the first attempt at a wider and more comprehensive review of an extensive range of project types.

2 Project Search Method

5 德国汉堡哈芬市改造后的码头。码头可以到达登船,但是由于污染不可能进行水上体育活动。即便如此,这里已经成功建成了一个集居住、商业、娱乐和旅游为一体的场所The redeveloped docks in the Hafen City in Hamburg,Germany. Access down to the places where boats can be boarded is possible but due to pollution no water-based physical activities are possible. Nevertheless, a new residential, business, recreational and tourist destination has been successfully created

6 中国深圳的一条新的海滨长廊,沿着滨水区连接着许多新住宅区旁的区域。晚上光线充足,供安全使用A new promenade in Shenzhen in China, running along the waterfront and linking many sectors near new residential areas. It is well-lit at night and feels quite safe to use

Projects to include in the review were sourced by applying the following criteria, which are broad and inclusive rather than narrow and exclusive (for the first collection)[31]:

1) Projects should have been planned and designed to give access to water of any type and at any scale broadly within an urban setting (but could include more rural locations on the edge of a city).

2) They could be from anywhere in the world but have been constructed mainly within the last 10-15 years (although some older major projects were included since they were critically revisited by some journals and provided many lessons from a longer term perspective).

3) They should have appeared as① a critical article in a respected professional journal, ② have been a competition winner,③ have won a prize awarded by a professional organisation, ④be listed on websites presenting high quality design projects which have received critical acclaim, or a combination of any or all of the above.

4) There should be sufficient information available for assessment — given that no site visits were possible for most projects (although some examples had been visited by team members and/or were quite well known directly).

5) Be visible as built projects in recent photographs and, especially, via GoogleEarth(especially through StreetView), showing them some time after they were first constructed and in use (in order to avoid perfect photos from the designers affecting the impression given).

Table 1 shows the main journals and websites,their publisher, country of origin and focus of coverage used for identifying the projects. An initial trawl led to the identification of almost 400 potential projects which was then reduced to 172 examples which really stood out. This number became the database of evidence for the review.The complete set of projects will eventually be made available as a searchable database but there is no space in this paper to list them individually.

3 Method of Critical Review

The review was undertaken both qualitatively and quantitatively. Reading the comments written in jury decisions, in the articles, award citations and on the review websites, revealed how each was appraised by peers. This was checked by the researchers (landscape architecture-qualified staff at the Chair of Landscape Architecture at the Estonian University of Life Sciences) as well as examining the projects using GoogleEarth and Streetview. Thematic analysis of the projects was undertaken using a set of pre-defined factors which formed criteria for site assessment in a number of tools (such as the Green Flag Awards④, Project for Public Space⑤, SpaceShaper⑥and so on). From each of these projects a number of themes was derived and comparison made between each project in relation to these themes. This was prepared as a qualitative overview. It is a summary of this which is presented in this paper. The detailed method and results of the quantitative study will be reported elsewhere once analysis has been completed.

Figures 1-3 show some basic characteristics of the samples — the range of countries/regions where they are located, the type of blue space they occupy and the type of land/water interface.

4 Analysis and Results

4.1 General Design Aspects

The view to the water, the land-water interface, how the design incorporates the presence of water, the suitability of the design (including elements and materials) to the place context and place affordances are the main factors determining the outstanding and the most aesthetically appealing projects. The design innovation and design sustainability are also important factors. Each of the reviewed projects included some specific feature or set of features as a major part of the design concept which contributed to their unique character, such as a reference to the former use of the site, for example ports or harbours, and the incorporation of elements into the design such as cranes, railway tracks, bollards and other structures large and small. In other examples a strong, bold focal feature — not necessarily art as such, though this could also be found — gave a new identity and focal point, a strong image (which also helped with the brand) and means of creating a new place.

Many examples used the water as a means of establishing the new or restored identity of the place, for example the imaginative ways in which designers brought land and water together physically or visually, maximised the aesthetic and sensory impact or used design to screen out the urban background in order to focus on the water.

It was also possible to see a certain contemporary“look” to many projects in the way that forms, colours,materials and textures were used. This is because designers look to precedents and there are stylistic movements which inevitably affect what people do,as in all design professions, even when designers try to be individualistic and unique.

It is notable that, compared with green space projects, owing to the often high degree of construction required at waterfronts, unique solutions are more common in blue space projects.It is often found that structures perform dual roles as edge protection and water access provision using interesting combinations of aesthetically designed and structurally engineered solutions.

Larger sites are normally subdivided into different functional and aesthetic zones. Some may divide formal (e.g. sports) from informal activities,different types of children’s play, different types of vegetation or different types of water. This can also increase the attraction and interest of the site by providing a variety of aesthetic experiences,different wildlife and also reduce the sensation of crowding by visually separating spaces so that the site cannot be seen all at once.

4.2 Potential for Increasing Physical and Mental Health and Wellbeing

All sites, apart from the very small interventions such as water features, offer good potential for increased physical activity, even if this is solely landbased. Foremost among these is walking and jogging/running while other exercise facilities and formal or informal sports are also very widespread.

The sites are almost all well-designed for providing opportunities to gaze at the view, to sit alone, to contemplate and so on but owing to the popularity and draw of the water’s edge solitude is often a problem except perhaps at certain times of the day. In the larger sites the main places for solitude are away from the water’s edge, perhaps in the vegetation immediately behind the waterfront(where this is the case).

Most sites were found to be rather urban in character so that the possibility to put the urban context out of sight and mind is less possible,perhaps with less potential for stress reduction than when the views to the water are open to the horizon, even if the city is right behind the viewer.

4.3 Accessibility

In the vast majority of cases the site was easily accessible on foot, by bicycle and from public transport. Car access was also often good, even in inner city areas, due to the provision of car parking.Car parking was more of a standard feature in projects in the USA and Australia — where there is more of a car-borne society — than in eg Germany or China.

In a significant minority of cases access to the area from the water is also part of the design. In some cases, this was from passenger ferries which have terminals next to the new park, in others there are marinas or small docks where pleasure boats can tie up and allow people to disembark in safety.

Accessibility within the site was also a strong feature of most projects — even in situations where the terrain was quite steep, ramps supplemented steps in gaining access down to the water. In a few limited examples it was not physically possible to make everywhere universally accessible but these were a clear minority. In sites which are not narrow and linear in form internal circulation is important — connecting different areas or zones within the site as well as offering a range of different paths around the site.

Bicycle access was generally possible although cycling within many sites was not and there seemed,from the evidence available, to be inadequate cycle parking in many sites. This depends on the cycle culture of different countries and it was not an issue in eg the Netherlands or Denmark.

Seaside and lakeside areas are mainly developed with direct access into the water as a key objective — and many are there to enhance access, especially for older or disabled people or to create safer and less damaging access in ecologically sensitive areas. Inner-urban rivers and former docks pose greater challenges and the designers tend to try to give opportunities for closer proximity and visual and sensory access but cannot, due to hydrological or water quality reasons, allow people to get into the water directly. The same is true of projects which combine water treatment through vegetation filtration systems with a park. People cannot be allowed direct contact but in all other respects the area is a wonderful place, especially to see water-based habitats and wildlife (Fig. 4).

In some projects ramps and steps have been incorporated as key features of the design and made the central concept of the project, with a form which is integral into the aesthetic quality evoked by the project. Handrails are also necessary items to help people use both steps and ramps — they can make a real difference when older people are frequent users.

Linkages from one site to another featured quite often — in some areas, such as the former docks of Manhattan, a number of small individual parks have been designed which are linked by walkways, forming a more extensive system.Coastal promenades, long distance paths and riveredge walks are also found to help in connecting different areas and also offer ways for people to connect into the larger structures.

Thus we can conclude that a key feature of success is a well-thought out accessibility strategy.This involves not only the planning and design of the site but how to get there. This involves planning together with authorities responsible for transport, road management, occasionally railways or metros and sometimes harbour authorities. The walkability or cycle-ability or streets around sites and aspects such as safe road crossings play a role as does the location and walking distance of bus stops, metro stations and car parking.

4.4 Interaction with Water

A key aspect of all projects reviewed was to maximise the potential for engagement or interaction with water. While in a number of cases it is not possible for people to come in direct contact with water for practical or safety reasons,visual and other sensory contact is an extremely important part of any project and in some cases it is very creatively achieved.

In some projects the site lies next to an embanked or canalised river or dockland where it is impossible to gain physical access. On the adjoining quayside or embankment water features have been installed which provide interaction with water jets or fountains — children and adults both enjoy splashing or being soaked by the jets in hot weather. In other cases, the site is nowhere near a natural waterbody but the appeal of a fountain or water feature is so strong that installations feature as focal points in a new park or urban square. This is in part due to the movement and changing nature of water as a result of its fluid state — jets, mists,mirror-like surfaces, swift currents, crashing waves,tides and so on demonstrate the dynamic quality of water which is such a contrast to the land.

In situations where there are vertical dock walls or flood retention embankments the site is often high above the waterbody. Opportunities to enable people to descend down towards the water are key aspects of the design in a number of projects. This may include installing structures which float or else may be submerged during flooding episodes. It may also be possible for boats to tie up and use the lower-level terraces or quays,so increasing the interaction with the water and water-based activities even in cases where the water itself is not too clean (Fig. 5).

Closer access obtained by siting piers or other decking structures down by the water can also be incorporated in projects with river re-naturalisation as an aim — the river may be swift and volatile but the chance to get close, even if a bit risky, can provide a special experience — akin to the sublime— which may contribute to a feeling of escape from the city and help in mental restoration.

Interaction with water at the beach —whether at the seaside or lake side — is clearly a long-standing and popular activity. Many projects incorporate restoration of beaches and beachfront facilities, even to the extent of importing sand and using structures to prevent the beach washing away.Vegetation restoration is also a feature of many projects. This means that, while going into the water is still the main focus, built structures play a more important role in mediating between people and the land/water interface.

4.5 Seating and Opportunities for Social Interaction

All projects reviewed pay special attention to seating provision. Some sites are equipped with large numbers of standard benches and from the visual evidence these are well-used. In some places picnics and barbecues are popular and tables, often supplied with grills, are also placed for this — which is associated with some cultures more than others. Bench designs may be off-the-shelf units (cost effective, easy to maintain etc) or made specially for the project.

There is also a major trend for seating to be built into the design in a more fundamental way — using terraces, steps and low walls as flexible structures with many affordances and with a lower need for maintenance as well as keeping sites simpler and less cluttered by lots of objects.

In some examples, where there are tides and a warm sea, steps leading down into the water can provide seating which is half-in and half-out of the water at any time of the tide, ideal for older or disabled people to enjoy the feel of water on their bodies. Floating structures may also provide the same seating and dipping of feet into the water but they respond to changes in water level.

Another popular type of bench is a fixed or moveable sun-bathing bed with a sloping section for sitting, lying, reclining etc. These are especially popular in a number of inland artificial “beaches”which provide sunbathing opportunities in the middle of the city. They are also useful in places where the beach is rocky, where there is no beach or where damage and erosion are problems.

4.6 Microclimate Amelioration

Waterfront areas are frequently exposed to strong sun and wind, to rain storms or to freezing conditions. Keeping them comfortable to use all year round can be a challenge. Since many sites in inner urban areas are devoid of vegetation or only have limited planting (such as former ports and industrial areas) they are often particularly exposed to the elements but, due to the lack of soil and drainage problems, pose problems for tree establishment. In any case, since trees or bushes take time to grow to a size where they can provide good shade or shelter, many project, while featuring planting, also use constructed elements to do the job instead or as well as trees.

Micro-climate sensitive design is a feature of a number of successful projects — of course, with different solutions in different places. It is clear that much thought and ingenuity has gone into this aspect in many sites. Shade (and rain) umbrellas,canopies which can be furled and unfurled, slatted overhead frames with climbing plants and closely spaced semi-mature trees (in order to get an instant result) are examples of good solutions.

Where there is adequate vegetation already then the designers have recognised that keeping it and managing it while adding to it for the longer term is important. Coastal sites offer challenges for growing trees and woody plants due to salt, winds,rocky soils and so on so the solution of planting and the selection of the correct species or varieties may not be as simple as for a regular park.

Temporary installations can be used to create shade in summer or shelter in winter, for example, or the same structures can perform dual functions, such as some types of shelters fond on a number of sites.

4.7 Site Management/Maintenance

For almost all the projects reviewed, good site management and maintenance was an important factor. There was little evidence of damage,vandalism or worn out vegetation in any sites and almost all were well-equipped with litter bins, which appeared to be well-used and regularly collected.

In many projects the design, use of materials and quality of construction helps towards ensuring that management and maintenance is likely to be cost effective and straightforward. Simplicity is often a feature of the design as is the use of standardised elements which can easily be replaced or repaired if necessary.

Good maintenance is one signal to users that a place is cared for and this translates into a message that the site is safe and welcoming to use.Damage and vandalism are usually more likely in run-down neighbourhoods and in places where there is little use at night (or where anti-social activities take over at night). Few of the sites which were to be found in such conditions showed any such problems.

4.8 Safety and Security

Safety in relation to the water is clearly an important issue. In projects in eg the USA, railings along edges are normal but in other countries there are fewer of these and it is theoretically possible to fall off edges. This means a balance has to be struck between too little and too much risk.

Provision of water safety equipment such as life-rings or equipping beaches with lifeguards and boats etc is surprisingly minimal in many projects,even those with sea swimming access. It may be that the evidence is not available, yet we found plenty of photos of sites at the height of summer with little or no equipment.

Personal safety, eg from crime, did not appear to be a major problem. Designers are now aware of how to make sites feel safer by reducing the availability of locations within the design where anti-social or illegal activity can take place, by good lighting at night, by ensuring that places police themselves as a result of plenty of people using them and so on (Fig. 6).

Most sites had good vehicular access for maintenance purposes which would also facilitate access by ambulances or other emergency vehicles.This ensures that any accidents can be dealt with quickly.

4.9 Food Sales and Eating Opportunities

In all sites visitors are generally more likely to spend more time there by taking refreshments.Picnicking is available either informally or using tables,while in a number of sites grilling and barbecuing are popular and well-provided for — this is somewhat culturally dependent. Food sales, ranging from ice cream stalls to full-blown restaurants, bars and cafes are also popular features of many sites.

5 Discussion and Conclusions

We can see from the results presented above that waterfront developments and water-accessibility projects form a major part of landscape architecture and urban design practice at the moment and this has been a rising trend since the initial projects were started following de-industrialisation and new port technologies for example, in the 1980s onwards,as well as the need to introduce better means of dealing with storm water and other factors. Planners and designers are clearly aware of the need to make such places attractive, iconic, accessible, safe, easy to maintain and offering as close a contact to water as is possible given practical and other constraints. All the sites we reviewed aim to increase the potential for physical and mental health and wellbeing improvement by offering opportunities for physical activity, for socialising, relaxing, getting closer to nature, soaking up the sun and de-stressing. It is also clear from the evidence that the vast majority of the sites are extremely well-used wherever they are located and that in dense cities with little green space, blue space offers an additional or substitute environment.

Of course, there are limitations in this study.While the sample of sites is large, at 172, this represents only the best and most critically acclaimed projects we could find. It is impossible to collect information on all projects which exist if they are not visible in publications or websites. Furthermore,the peer-reviewing process is mainly carried out by other landscape architects who may not evaluate factors which may have negative impacts on the project sites, such as ecological damage. In addition,the fact that the vast majority of the projects could not be visited in person by the researchers means that potentially a lot of subtleties associated with many sites might have been missed. With the availability of tools like GoogleEarth and Google StreetView as well as the photographs uploaded by visitors, the use of “big data” and social media as a means of obtaining data for use in research is becoming increasingly acceptable. The ability to look at sites over time also offers fascinating possibilities for examining projects, especially landscape architecture projects where their growth and development over tine is important.

The designers of the projects may or may not have had human health and well-being at the forefront of their minds when developing their plans. However, in these highly acclaimed examples we can see quite clearly what main elements have been included which research has identified as being important for facilitating health and wellbeing benefits. Thus this attempt at post-occupancy evaluation has already revealed, without the further in-depth analysis being carried out to be reported elsewhere, a number of key aspects which can form guidelines for planers and designers.

We can say, therefore, that urban blue spaces have the potential to play an important role in the health and well-being of urban residents and that, as part of the regional landscape systems of rivers, lakes and the sea, more research needs to be undertaken and such spaces need to be properly taken into account by urban planners and designers.

(This paper is revised on the basis of the speech delivered by the author at the International Landscape Architecture Symposium in 2018.)

Acknowledgements:

The author wishes to acknowledge the help of his colleagues,especially Himansa Sekhar Mishra, in selecting and assessing the projects reviewed in this paper.

Sources of Figures and Table:

Fig. 1-3 © Himansu Sekhar Mishra; Fig. 4, 6 © Simon Bell;Fig. 5 licensed under Creative Commons; Tab. 1 © Himansa Sekhar Mishra.