Retrospective study on mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasms from five European centres

2019-10-30MelissaFrizzieroXinWangBipashaChakrabartyAlexaChildsTuLuongThomasWalterMohidKhanMeleriMorganAdamChristianMonaElshafieTahirShahAnnamariaMinicozziWasatMansoorTimMeyerAngelaLamarcaRichardHubnerJuanValleMairadMcNamara

Melissa Frizziero, Xin Wang, Bipasha Chakrabarty, Alexa Childs, Tu V Luong, Thomas Walter, Mohid S Khan,Meleri Morgan, Adam Christian, Mona Elshafie, Tahir Shah, Annamaria Minicozzi, Wasat Mansoor, Tim Meyer,Angela Lamarca, Richard A Hubner, Juan W Valle, Mairéad G McNamara

Abstract BACKGROUND Mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasm (MiNEN) is a rare diagnosis, mainly encountered in the gastro-entero-pancreatic tract. There is limited knowledge of its epidemiology, prognosis and biology, and the best management for affected patients is still to be defined.AIM To investigate clinical-pathological characteristics, treatment modalities and survival outcomes of a retrospective cohort of patients with a diagnosis of MiNEN.METHODS Consecutive patients with a histologically proven diagnosis of MiNEN were identified at 5 European centres. Patient data were retrospectively collected from medical records. Pathological samples were reviewed to ascertain compliance with the 2017 World Health Organisation definition of MiNEN. Tumour responses to systemic treatment were assessed according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours 1.1. Kaplan-Meier analysis was applied to estimate survival outcomes. Associations between clinical-pathological characteristics and survival outcomes were explored using Log-rank test for equality of survivors functions (univariate) and Cox-regression analysis(multivariable).RESULTS Sixty-nine consecutive patients identified; Median age at diagnosis: 64 years.Males: 63.8%. Localised disease (curable): 53.6%. Commonest sites of origin:colon-rectum (43.5%) and oesophagus/oesophagogastric junction (15.9%). The neuroendocrine component was; predominant in 58.6%, poorly differentiated in 86.3%, and large cell in 81.25%, of cases analysed. Most distant metastases analysed (73.4%) were occupied only by a poorly differentiated neuroendocrine component. Ninety-four percent of patients with localised disease underwent curative surgery; 53% also received perioperative treatment, most often in line with protocols for adenocarcinomas from the same sites of origin. Chemotherapy was offered to most patients (68.1%) with advanced disease, and followed protocols for pure neuroendocrine carcinomas or adenocarcinomas in equal proportion. In localised cases, median recurrence free survival (RFS); 14.0 mo(95%CI: 9.2-24.4), and median overall survival (OS): 28.6 mo (95%CI: 18.3-41.1).On univariate analysis, receipt of perioperative treatment (vs surgery alone) did not improve RFS (P = 0.375), or OS (P = 0.240). In advanced cases, median progression free survival (PFS); 5.6 mo (95%CI: 4.4-7.4), and median OS; 9.0 mo(95%CI: 5.2-13.4). On univariate analysis, receipt of palliative active treatment (vs best supportive care) prolonged PFS and OS (both, P < 0.001).CONCLUSION MiNEN is most commonly driven by a poorly differentiated neuroendocrine component, and has poor prognosis. Advances in its biological understanding are needed to identify effective treatments and improve patient outcomes.Key words: Mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasm; 2017 World Health Organisation classification; Mixed adeno-neuroendocrine carcinoma; Gastro-enteropancreatic tract; Digestive system; Neuroendocrine neoplasms; Survival outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Mixed tumours exhibiting both exocrine and neuroendocrine morphological features are frequently encountered by pathologists in routine practice, and can originate in all organs. Over the years, these tumours have been assigned variable designations,giving rise to huge inconsistency within the literature[1]. Since 2000, tumours from the gastro-entero-pancreatic (GEP) tract consisting of an exocrine and a neuroendocrine component, accounting for at least a third or 30% of the tumour mass, have been classified by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as separate entities from their pure counterparts[2-5]. In 2010, the WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system[4]named those mixed tumours mixed adeno-neuroendocrine carcinomas(MANECs).

MANEC is a rare and controversial diagnosis; data from the current literature are limited, almost exclusively derived from case reports and small retrospective series,and inconsistent, mainly due to differences across studies in patient inclusion criteria(e.g., disease stage, grade of differentiation of the two components, sites of origin),population size and interpretation of the 2010 WHO definition of MANEC. In fact,there is still large disagreement among authors on whether to include goblet cell carcinoids/carcinomas of the appendix[6]under the diagnosis of MANEC, and whether to consider mixed tumours composed by an adenoma and a well differentiated neuroendocrine component separately from MANECs with more aggressive histological features[7]. The median overall survival (OS) of affected patients varies greatly across the retrospective series, ranging between 10 to 78 months (any disease stage or disease stage not specified)[8-13].

The European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society (ENETS) clinical practice guidelines recommend that the management of MANEC should follow the standard of care for pure, grade 3, neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC)[14], since the neuroendocrine component in MANEC is most commonly poorly differentiated and predominant, both in the primary tumours and in distant metastatic sites[15]. However,other authors suggest treating MANEC according to the clinical practice guidelines for adenocarcinomas (ADCs) from the same site of origin, when the ADC component is prevalent and/or the least differentiated[7].

In 2017, the WHO classification of tumours of endocrine organs has renamed MANECs from the pancreas “mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasms”(MiNENs)[5], in order to better convey the variety of possible combinations between neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine histologies, extending the spectrum of the latter to incorporate “non-gland-forming” variants (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma or sarcoma) and precancerous lesions (e.g., adenoma). The term MiNEN currently only appears in the nomenclature for endocrine neoplasms arising from the pancreas.However, pathologists commonly extend the use of the phrase and apply it to mixed tumours meeting the diagnostic criteria and originating from any organ site[16].

It is worth noting that, since the diagnosis of MiNEN is based on a quantitative threshold, tissue biopsies may not be able to accurately discriminate between MiNENs and neuroendocrine neoplasms with a minor non-neuroendocrine differentiation (< 30%), or vice versa, potentially accounting for underestimation of the frequency of this diagnosis. As a result of the limitations of diagnostic methods, as well as the paucity and inconsistency of available evidence, the actual epidemiology and prognosis of MiNEN remains unknown.

Furthermore, identifying effective therapeutic strategies for MiNEN represents a major challenge, which can be mainly explained by; (1) the lack of high-quality evidence from large prospective trials, due to the rareness and limited awareness of this diagnosis outside the community of clinicians and researchers with interest in neuroendocrine neoplasms; and (2) the different sensitivity of the two histologies to conventional systemic treatments and radiotherapy; the selective treatment of one of the two components can favour the clonal expansion of the other, leading to the rapid development of resistance.

The present study aimed to collect data from a large, retrospective, multi-centre,series of patients with a diagnosis of MiNEN, for whom there was compliance with the 2017 WHO classification[5], confirmed by pathologists with expertise in neuroendocrine neoplasms, to inform clinicians on the clinical-pathological characteristics, biological behaviour and management of this poorly understood disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient and tumour samples

Consecutive patients with a diagnosis of MiNEN, as per the 2017 WHO classification[5], were retrospectively identified from 5 European Institutions, 4 of which are ENETS Centres of Excellence; The Christie National Health Service (NHS)Foundation Trust in Manchester (United Kingdom), The Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust in London (United Kingdom), University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust (United Kingdom), Edouard Herriot Hospital (Hospices Civils de Lyon) (France), and Cardiff and Vale University Health Board (United Kingdom).

All pathological samples, obtained by either surgical resection or tissue biopsy from primary tumours or metastatic sites, were reviewed by pathologists with expertise in neuroendocrine neoplasms, and fulfilled the 2017 WHO diagnostic criteria for MiNEN (each component accounting for at least 30% of the tumour mass)[5]. Only patients with a primary tumour from the GEP tract, or of unknown origin, where other primary sites were excluded, were considered eligible for inclusion in this study. Diagnosis by cytology (e.g., brushing or fine needle aspiration) was not permitted, as deemed not informative enough to allow an accurate diagnosis of MiNEN. Other exclusion criteria included; goblet cell carcinoids Tang subtype A,ADC ex-goblet cell carcinoids Tang subtype B and C[6], and amphicrine tumours. In fact, studies reporting on goblet cell carcinoids (any Tang subtype) indicate that these tumours rarely exhibit a neuroendocrine component exceeding 30% of the tumour mass[7,17], and seem to have a more favourable prognosis than patients with MiNENs[11,12].

Demographic characteristics, treatment modalities and clinical outcomes of eligible patients, and morphological data of corresponding tumour samples were collected from local medical records (approved by local audit committees). This study was approved by the Christie NHS Foundation Trust Audit committee (16/1806).

Due to differences in staging systems among tumours from different sites of origin,the disease stage was classified as follows; localised (Loc), if the tumour was amenable to curative treatment, whether or not loco-regional nodes were affected,and in the absence of distant metastases; advanced (Adv), if the tumour was not amenable to curative treatment, either because locally infiltrative or because of the presence of distant metastases.

Chemotherapy and chemo-radiotherapy regimens, used either in the Loc or Adv setting, were defined as “ADC-like” or “NEC-like” according to whether they were in keeping with the “standard-of-care” for the treatment of ADCs from the same site of origin or NECs, respectively.

The following endpoints were used to investigate patient and treatment outcomes;recurrence-free-survival (RFS) (defined as the time from the beginning of the initial curative treatment to radiological or clinical evidence of recurrence of the tumour or tumour-related death), progression-free-survival (PFS) (defined as the time from the diagnosis of Adv disease or the beginning of active palliative treatment to radiological/clinical evidence of progression of the tumour or death from any cause),and OS (defined as the time from the initial pathological diagnosis to death from any cause). For patients with Loc MiNEN who developed recurrent Adv disease, PFS and OS were also calculated from the time of radiological diagnosis of Adv disease or the beginning of active palliative treatment to the time of radiological/clinical evidence of further progression or death from any cause; these PFS and OS data were combined with those from patients with Adv disease “ab initio”, in order to increase the sample size of the Adv subgroup.

The date of data cut-off was the 28thof February 2018. The follow-up time was

estimated from the date of the first contact by the patient with the institution and the date of last follow-up visit, or contact, or death from any cause. The response to chemotherapy or chemo-radiotherapy was assessed according to the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1[18]. Frequency of imaging was performed as per institutional and ENETS guidelines[14](every 3 mo).

Statistical analysis

Microsoft excel was used for descriptive statistics, and “R” software was used for inferential statistics. Survival outcomes (median RFS, PFS and OS) were estimated by using Kaplan-Meier analysis (patients lost to follow-up were censored at the time of last follow-up visit or contact). Associations between clinical and pathological characteristics and survival outcomes were investigated by applying Log-rank test for equality of survivors function (univariate), and Cox-regression analysis(multivariable). Probability values (P) were considered to be statistically significant at a level < 0.05.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of patients and pathological data of tumour samples

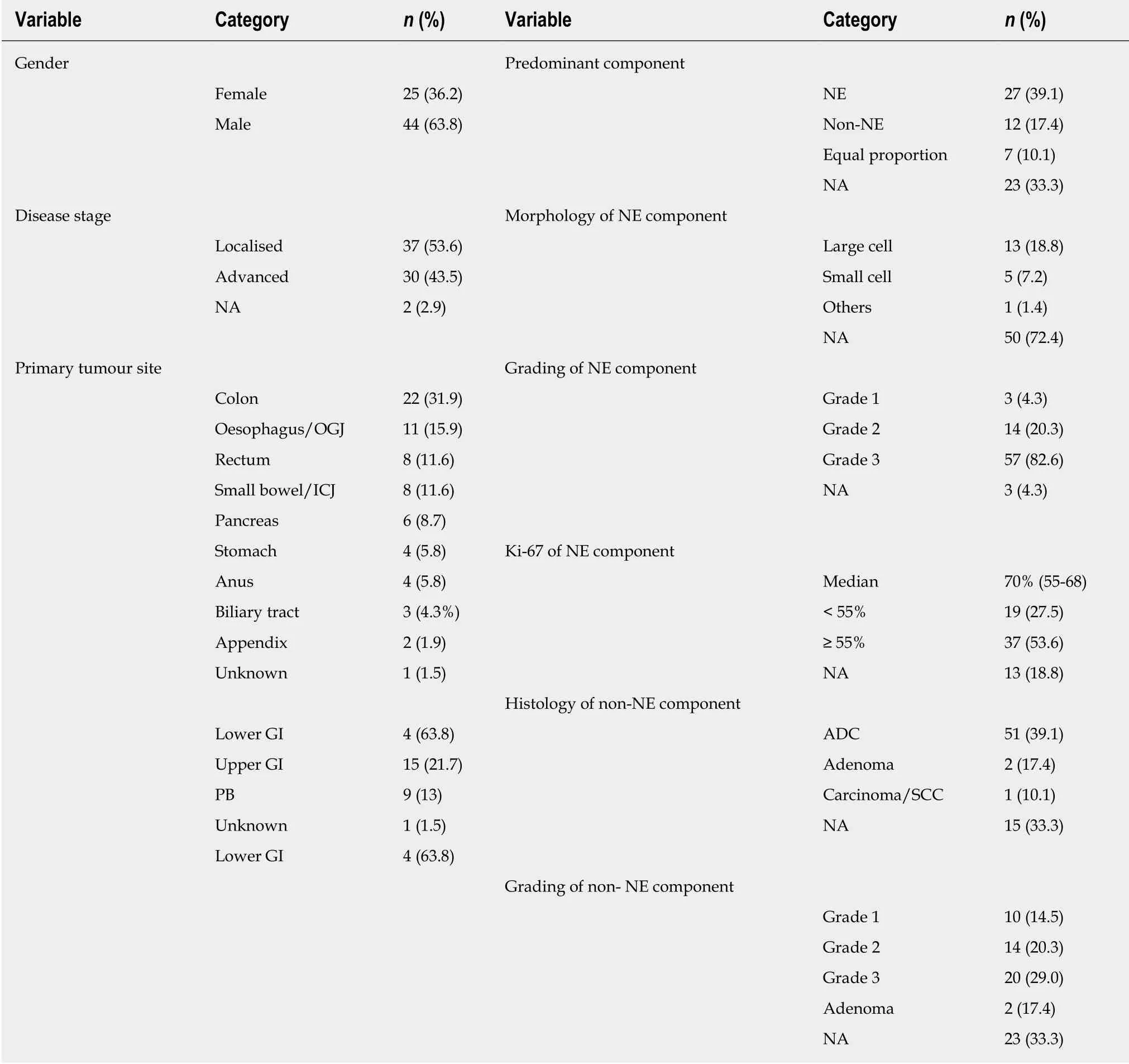

A total of 69 consecutive patients with a diagnosis of MiNEN (2017 WHO definition)[5]were eligible for inclusion in the study. The date of diagnosis ranged from the 1st of September 1980 to the 1st of August 2017. The median follow-up time was 11.5 months [95% confidence interval (CI); 6.5-13.5]. Baseline demographic and clinical/pathological characteristics are summarised in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1. The median age of patients at diagnosis was 64 years (range:34-89).

Pathological material for diagnosis (collection procedure; surgery 58%, biopsy 36.2%, unknown but not fine needle aspiration or brushings in 5.8%) was obtained from primary tumours in 50 cases (72.5%) and metastatic sites in 5 cases (7.2%),whereas the site from where the tumour tissue was retrieved could be ascertained in 14 cases (20.3%). The neuroendocrine component was predominant and poorly differentiated, grade 3, in 58.7% and 86.4% of cases for which this information was available, respectively. The median Ki-67 index of the neuroendocrine component(recorded for 56 patients) was 70% (range: 2%-95%). The predominant histology in MiNEN, and the morphological subtype of the neuroendocrine component was not available from pathological reports in 33.3% and 72.4% of cases, respectively.Immunohistochemical data on diagnostic samples of MiNEN are presented in Table 2.

Additional pathological material from synchronous or metachronous metastatic sites was available for 15 patients and consisted of a pure NEC in 11 (73.4%) cases, a pure ADC in 1 (6.6%), and an admixture of both histologies in 3 (20%).

Management and clinical outcomes of patients

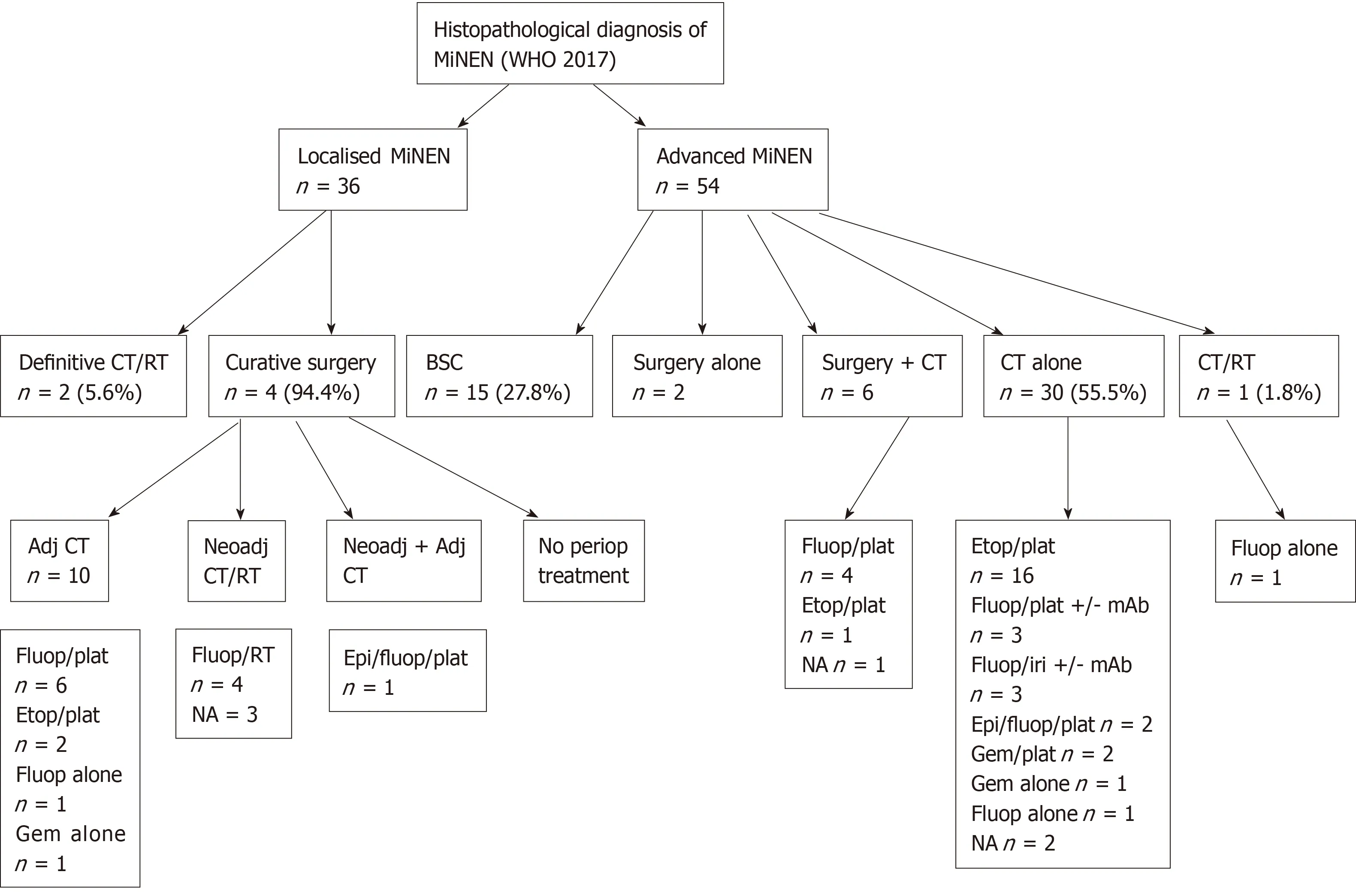

Treatment modalities of MiNEN was available for 36 patients with Loc disease and 54 patients with Adv disease, and are illustrated in Figure 1. The Adv subgroup included both patients who presented with Adv disease at diagnosis (n = 29) and patients who developed recurrent metastatic disease after initial curative treatment (n = 25).

Chemotherapy and chemo-radiotherapy regimens administered with curative intent in the Loc setting followed ADC-like protocols in 13/18 (72.2%) cases and NEClike protocols in 2/18 (11.1%) cases [for 3/18 (16.7%) patients, the chemotherapy regimen used was unknown]. Regimens of systemic treatment administered with palliative intent in the Adv setting were in keeping with ADC-like protocols in 17/37(45.9%) cases and NEC-like protocols in 17/37 (45.9%) cases [for 3/37 (8.1%) patients,the chemotherapy regimen used was unknown]. Descriptive associations between the predominant and/or most aggressive component in diagnostic samples, or second biopsies obtained at the time of diagnosis of Adv disease (pre-treatment), and chemotherapy or chemo-radiotherapy regimens used were possible for 30 patients(Supplementary Table 2); the choice of regimen (either NEC-like or ADC-like) was in line with the predominant or most aggressive component in 20 (67%) cases.

In the Adv setting, the response to first-line chemotherapy or chemo-radiotherapy was assessed for 30 patients; 2 (6.7%) had complete response (CR), 4 (13.3%) had partial response (PR), 13 (43.3%) had stable disease (SD) (disease control rate; 63.3%),and 11 (36.6%) had progressive disease (PD). Correlations between treatment response and predominant/most aggressive histology or chemotherapy/chemoradiotherapy protocols used were not interrogated, as individual subgroups were too small to allow reliable statistical analyses.

Eleven patients received second-line active treatment; 9 chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil-based in 6, gemcitabine-based in 1, cisplatin/etoposide in 1,cyclophosphamide/adriamycin/vincristine in 1), 1 chemo-radiotherapy and 1 debulking surgery with intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical-pathological characteristics in patients with a diagnosis of mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasm

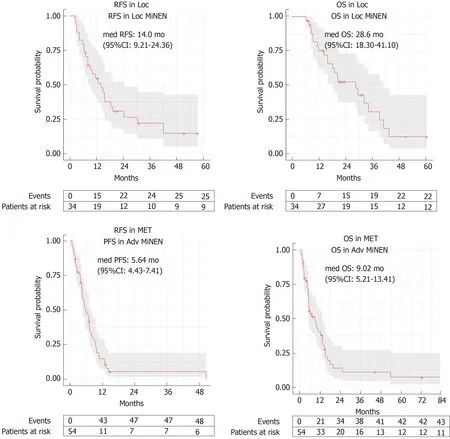

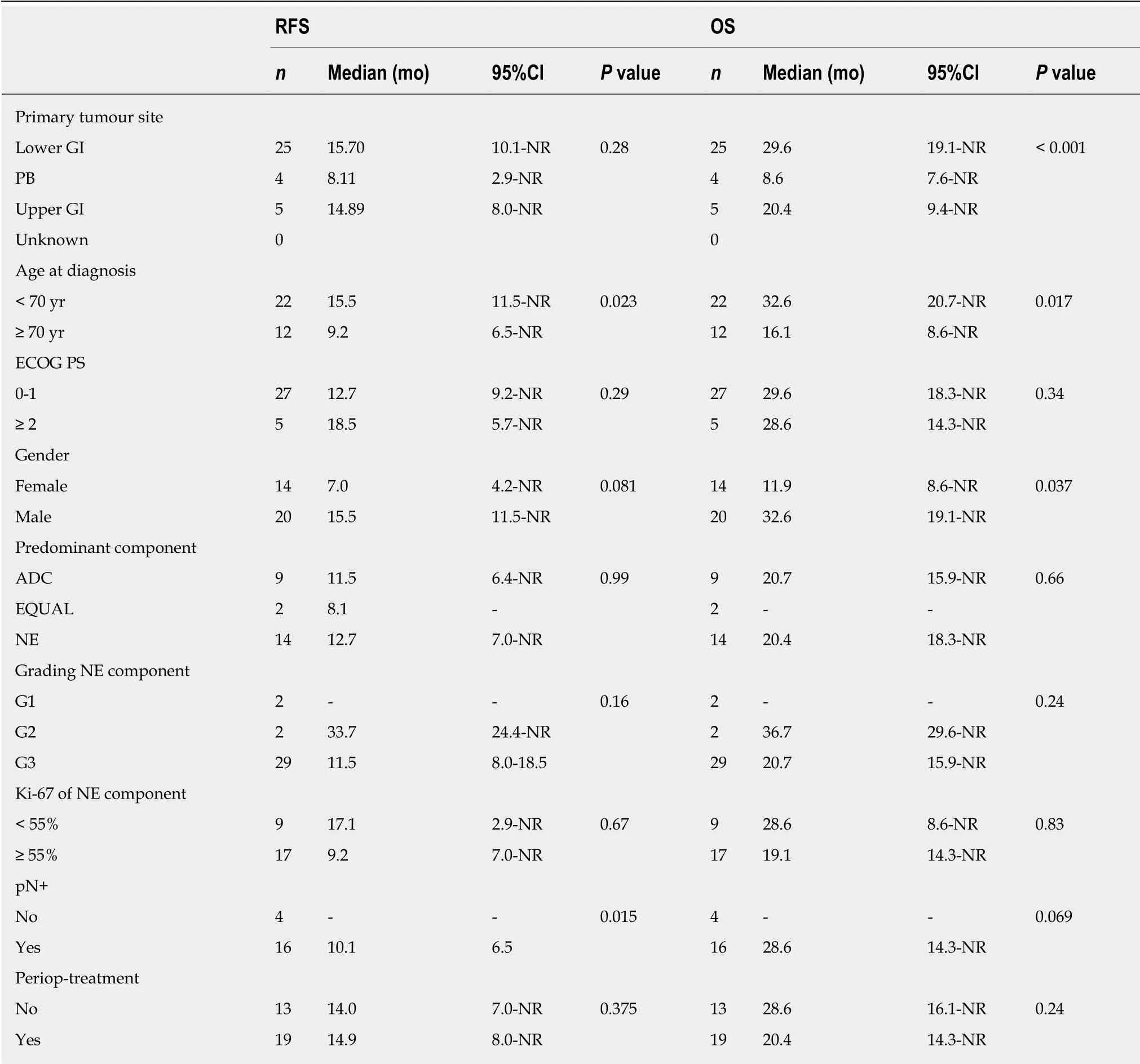

At the time of data cut-off, the median OS in the whole population was 15.9 mo(95%CI: 12.4-29.6) (whether or not death had occurred was unknown in 6 patients). In the Loc subgroup, 25 (67.6%) patients relapsed and the median RFS was 14.03 mo(95%CI: 9.21-24.36) (whether or not disease relapse occurred was unknown for 4 patients), and 22 (59.5%) died. The median OS was 28.6 mo (95%CI: 18.30-41.10)(whether or not death occurred was unknown for 3 patients) (Figure 2). Univariate analyses for RFS and OS in the Loc setting are presented in Table 3. The primary tumour site (lower gastro-intestinal, upper gastro-intestinal or pancreatico-biliary)significantly impacted on OS (P < 0.001), with MiNENs of pancreatico-biliary origin seeming to have the worst outcomes. An age at diagnosis below 70 years (vs ≥ 70) was a positive prognostic factor for both RFS (P = 0.023) and OS (P = 0.017). Female gender was prognostic for worse OS (P = 0.037) and was associated with a trend towards worse RFS, although not statistically significant (P = 0.081). The absence of local-regional lymph node metastases in post-operative specimens was prognostic for longer RFS (P = 0.015), and was associated with a trend towards improved OS,although not statistically significant (P = 0.069). Interestingly, neither the predominant component nor the receipt of perioperative treatment (vs surgery alone) impacted on PFS or OS. Multivariable analysis was considered but due to lack of complete data,the number of analysable cases for each subgroup was too small (n = 1-11) to enable reliable comparisons.

Table 2 Immunohistochemical data on diagnostic samples of mixed neuroendocrine nonneuroendocrine neoplasm

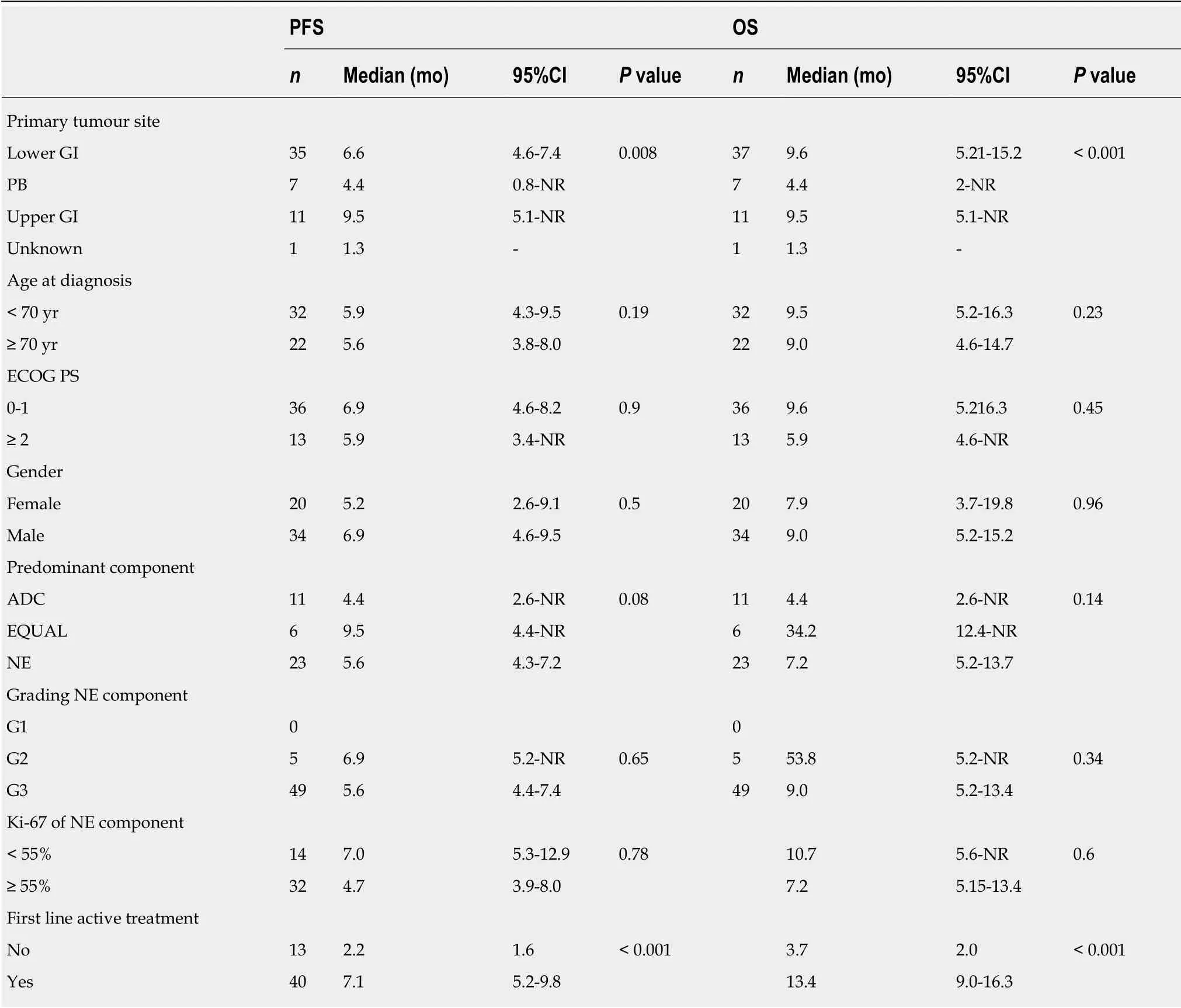

In the Adv subgroup, 29 (53.7%) patients had progressed and 43 (78.2%) had died,and the median PFS and OS were 5.64 months (95%CI: 4.43-7.41) and 9.02 months(95%CI: 5.21-13.41), respectively (whether or not disease progression or death occurred was unknown for 1 patient) (Figure 2). Univariate analyses for PFS and OS in the Adv setting are presented in Table 4. The primary tumour site (lower gastrointestinal, upper gastro-intestinal or pancreatico-biliary) significantly impacted on both PFS (P = 0.008) and OS (P < 0.001), with MiNENs of pancreatico-biliary origin seeming to have the worst outcomes. The receipt of first-line active treatment (vs best supportive care alone) was associated with significantly better PFS (P < 0.001) and OS(P < 0.001), whereas the predominant component did not impact on either survival outcomes. On multivariable analysis (Supplementary Table 3), the primary tumour site retained prognostic significance for OS (P = 0.016), and had “borderline”prognostic significance for PFS (P = 0.057). In contrast, the administration of first line active treatment lost significance for both PFS (P = 0.237) and OS (P = 0.523).

Univariate analysis for RFS, PFS and OS according to immunohistochemical data from tumour samples at diagnosis was also performed, and significant results can be summarised as follows; in the Loc setting, CK-7 positive staining was associated with shorter RFS (P = 0.021) and OS (P = 0.035), and CDX-2 positive staining was associated with improved OS (P = 0.009). In the Adv setting, Chromogranin A positive staining was associated with shorter PFS (P = 0.039).

Figure 1 Treatment modalities of patients with a diagnosis of mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasm according to disease stage.

DISCUSSION

This current study is one of the largest reporting on a population of patients with a diagnosis of MiNEN in the literature, with expert pathological review confirming the diagnosis. The results of this study indicate that, most commonly, MiNEN is diagnosed in men and arises from the colon-rectum or oesophagus/oesophago-gastric junction. These data closely mirror those from a German, single-centre, retrospective study by Apostolidis et al[19]which included 58 patients with a diagnosis of MiNEN. In addition, MiNEN has an aggressive biological behaviour, usually driven by a poorly differentiated neuroendocrine component. In nearly all cases, the non-neuroendocrine component is of ADC histology. These findings are in line with those from other retrospective cohorts of MiNENs where the neuroendocrine component was predominant in 50%-66.7% of tumour samples analysed[15,20-23]and poorly differentiated in 59%-100% of tumour samples analysed[12,15,19-26], and the nonneuroendocrine component was of ADC or adenoma histology in 66.7-100% of tumour samples analysed[10,15,20-27]. In addition, in the present study, the NEC component of MiNEN was predominantly of large cell morphology. Although this information was available only for a small proportion of cases (16; 23%), two other studies reported similar findings; a large cell NEC component in 41/42 and 10/10 MiNEN samples, respectively[20,24].

Interestingly, the present study suggests that, in MiNEN, the metastatic process is dominated by a single component, which is usually of NEC histology. This is corroborated by similar findings from an Italian and two Asian studies reporting on patients with GEP MiNENs[15,20,23], and carries an important implication; biopsies of metastatic sites may not capture both the tumour components, deceptively leading to a diagnosis of pure NEC or ADC, especially in Adv cases when surgical material for full sampling of the primary tumour is not available. This may also explain why the majority of cases, in the present cohort of MiNENs, were diagnosed at a Loc stage,which is unexpected for an aggressive disease; a proportion of Adv MiNENs may be misdiagnosed due to limitations of tissue biopsies.

Figure 2 Kaplan-Meier curves for recurrence-free survival and overall survival in the localised stage subgroup, and for progression free survival and overall survival in the advanced stage subgroup.

Consistent with other studies from the literature[8,11,19,20,22], curative surgery was the preferred treatment for Loc MiNEN, and pre-operative and/or post-operative treatment was delivered to between a half and three quarters of resected cases.Chemotherapy and chemo-radiotherapy regimens in the Loc setting were most commonly adherent to the clinical practice guidelines for pure ADCs from the same sites of origin; this might be explained by the lack of solid evidence advocating the use of peri-operative chemotherapy or chemo-radiotherapy for potentially curable pure neuroendocrine neoplasms.

In the present study, palliative chemotherapy was the most common treatment offered to patients with Adv disease, whereas in the majority of reported studies on MiNEN from the literature, surgery, either alone or in combination with palliative chemotherapy, is the preferred management for this subgroup of patients[8,20-22,26,28,29].This discrepancy might be explained by a selection bias, since most of those studies were conducted in surgical cohorts, only including cases of MiNEN diagnosed by surgical excision[8,20-22].

There is variability within the literature with regard to chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy regimens (ADC-like or NEC-like) used in the palliative setting[8,19,20,22,29],and the criteria driving the choice of the regimen remains unexplained. Similar to the study by Apostolidis et al[19], in the present series, first-line chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy regimens were in line with ADC-like or NEC-like protocols in equal proportion. In addition, the choice of the regimen seemed to be based on the predominant or most aggressive histology. Noticeably, in a proportion of cases, ADClike platinum-based regimens (e.g., 5-fluorouracil/oxaliplatin or 5-fluorouracil/irinotecan) were preferred, despite a predominant or more aggressive neuroendocrine component; a possible explanation is that clinicians opted for suchcombinations, which have shown anti-tumour activity in small retrospective series of NECs[30,31], in an attempt to target both the components.

Table 3 Univariate analyses for recurrence-free-survival and overall survival in patients with a diagnosis of localised mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasm

The results of the present study indicate that MiNEN has a poor prognosis, with a high likelihood of recurrence or progression after a short period of time from the initial management. Survival outcomes of MiNEN were close to those of pure GEPNECs[32-34], and such a similarity was more evident in the Adv setting. Similarly,disease control rates to first-line palliative chemotherapy, which were consistent with those from other series of MiNENs (60%-68%)[19,20], were close to those of pure GEPNECs (64%-100%)[32-34].

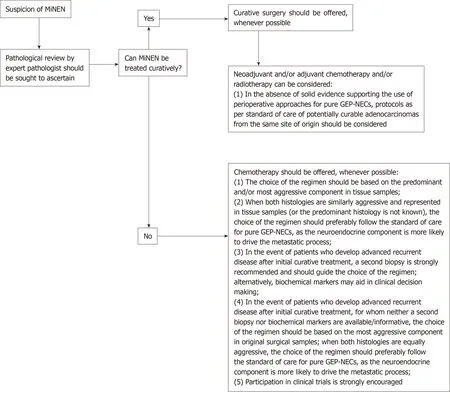

The present study summarises real-world data on an under-researched diagnosis,providing suggestions for clinical practice (Figure 3). However, there are limitations which are worth acknowledging. Firstly, it is a retrospective study and, therefore, the data reported may not be as accurate as in prospective clinical trials; information on a number of key pathological features (e.g., predominant component, histology of nonneuroendocrine component, morphological subtype and Ki-67 value of the neuroendocrine component, and immunohistochemical data) could not be retrieved from medical records or pathological reports in non-negligible proportions ofpatients, and further pathological review of the samples was not feasible. Although it would be interesting from a scientific standpoint to obtain the Ki-67 value and the morphological subtype (small cell vs large cell) of the neuroendocrine component from a larger number of patients, neither are proven prognostic or predictive factors in this disease subgroup and, therefore, currently, this information is of limited relevance for clinical practice. Secondly, the results of univariate and multivariable analyses have to be interpreted with caution, as the small sample size of comparator subgroups would not permit reliable deductions. Furthermore, survival outcomes of the Adv subgroup might be biased by the inclusion of patients who developed metastatic recurrent disease after initial curative treatment for Loc MiNENs; some of those patients who had received previous perioperative treatment, might have developed more chemo- and/or radiotherapy-resistant phenotypes, that might have negatively influenced the outcomes of the whole Adv subgroup. Lastly, there may be inaccuracies in diagnosis for those patients (around a third) having biopsy samples as the only diagnostic material, since verifying the 30% threshold for each component based on a limited amount of tissue might be challenging. However, biopsy samples were reviewed by expert pathologists, who based their conclusion on either the presence of an admixture of equal proportions of the two components within the tumour sample, or the evidence of mixed exocrine/neuroendocrine features on further tumour samples from the same patient.

Table 4 Univariate analysis of progression-free survival and overall survival in patients with advanced mixed neuroendocrine nonneuroendocrine neoplasm

Figure 3 Algorithm of suggestions for clinical management of patients with a diagnosis of mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasm.

To conclude, due to limitations in diagnostic methods (insufficient amount of tumour tissue provided by biopsies) and criteria (a quantitative arbitrary 30%threshold for each component), the actual incidence of MiNEN may be underestimated in general clinical practice. To pursue an accurate diagnosis of MiNEN, and therefore deliver the most appropriate management, in the presence of a tumour from the GEP tract exhibiting a mixed histology and/or an unconventional behaviour on standard treatment, the tumour sample should be reviewed by pathologists with expertise in neuroendocrine neoplasms. Collection of additional tumour material from metastatic sites is also advisable to optimise the choice of treatment.

Recent molecular and genetic studies on MiNEN have uncovered shared molecular vulnerabilities between the neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine components[24,25,35], suggesting a potential role for targeted treatments against both the components, overcoming the long-standing problem of their differential sensitivity to conventional chemotherapy and chemo-radiotherapy. Sample biobanking and wider molecular analyses are paramount to forward the biological understanding of this rare disease, to inform novel drug development treatments and patient allocation to early-phase biomarker driven clinical trials. Liquid biopsies may aid in overcoming the limitations of tissue biopsies.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research motivation

Although rare, when encountered, MiNEN represents a therapeutic riddle for clinicians, as there is still uncertainty as to how patients with this diagnosis should be managed, in the absence of data from clinical trials. In addition, the actual incidence of MiNEN remains unknown.Therefore, data from large retrospective studies is warranted.

Research objectives

The present study was designed to provide insights on the epidemiology and prognosis of MiNEN from the gastro-entero-pancreatic tract (GEP), as well as on commonly applied therapeutic approaches, with the ultimate aim of providing some guidance for clinical practice.

Research methods

To this end, a large retrospective, multicentre collection of clinical-pathological and survival data, and treatment modalities from patients with a diagnosis of GEP-MiNEN was carried out.Original diagnostic samples were reviewed by pathologists with expertise in neuroendocrine neoplasms to ascertain compliance with the most recent diagnostic criteria for MiNEN (WHO classification 2017). Potential differences in survival outcomes between subgroups with distinct clinical-pathological characteristics were also investigated.

Research results

MiNEN is most commonly diagnosed in the colon-rectum and oesophagus/oesophago-gastric junction. The neuroendocrine component is almost always grade 3, and is most commonly the predominant histology in both the primary tumour and distant metastatic sites. The nonneuroendocrine component is of adenocarcinoma histology in most cases. Patients with potentially curable MiNEN usually receive curative surgery, in combination or not with preand/or post-operative chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy as per standard of care for pure adenocarcinomas form the same sites of origin. Patients with advanced MiNEN most commonly receive chemotherapy following protocols for pure neuroendocrine carcinomas or adenocarcinomas from the same sites of origin. The prognosis of MiNEN is poor; patients with initially curative MiNEN have a high likelihood of recurrence (around 2/3 of cases), with half of cases developing disease recurrence within the first 12 months from curative treatment. Patients with advanced stage MiNEN progress soon after the beginning of palliative treatment and have survival outcomes very close to those of pure GEP-NECs.

Research conclusions

The incidence of MiNEN is likely underestimated, as tissue biopsies may not be able to capture both the histologies; it is a predominantly metastatic disease, and metastatic sites are usually occupied by a single component (most frequently G3, neuroendocrine). A pathological review of the samples by pathologists with expertise in neuroendocrine neoplasms is strongly recommended. A second biopsy from metastatic sites is encouraged, whenever possible,especially on disease progression. Systemic treatments directed against one of the two components have limited efficacy. Novel drug development should exploit common biological vulnerabilities between the two components. Biological studies and liquid biopsies may aid in unveiling the molecular landscape of MiNEN, and informing drug development and clinical trial design.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Gut-liver axis signaling in portal hypertension

- Role of tristetraprolin phosphorylation in paediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease

- STW 5 is effective against nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs induced gastro-duodenal lesions in rats

- Superior gallstone dissolubility and safety of tert-amyl ethyl ether over methyl-tertiary butyl ether

- Gender differences in vascular reactivity of mesenteric arterioles in portal hypertensive and non-portal hypertensive rats

- Construction of a replication-competent hepatitis B virus vector carrying secreted luciferase transgene and establishment of new hepatitis B virus replication and expression cell lines