多面性

—— 建筑转型的工具

2019-10-17安娜玛利克韦伯AnnaMarijkeWeber

安娜·玛利克·韦伯/Anna Marijke Weber

钱芳 译/Translated by QIAN Fang

本文从建筑的多面性潜能角度探讨了后矿业改造项目的设计策略。矿业建筑体以各种不同的方式与更广阔的文化背景产生着关联。在一个以矿业为主的社区内,采矿是日常活动的重要组成部分,比如在语言或方言中会有“矿井话”,比如特别的空间活动,为了某种用途如链条清洗而特别设计的建筑类型,由此会形成一种特别的区域性集体记忆。矿业活动在不同地区的历史发展中扮演着重要角色,可以决定政治活动是否能够获得支持,从而产生结构性影响。

矿业活动的物质表达可以体现在各种尺度上:景观、城市、社区、标志性建筑物,空间上的独特特征的形成基本上都是受到矿业发展背景下各种决策的影响。虽然彼此相关,地上和地下部分的建筑逻辑是不同的:一个是要符合原材料的地质形式,一个是建筑体在城市中的形式。为了符合工业化过程中的社会发展目标,矿业建筑体通过其空间形式积极传递着工作、繁荣及发展的理想。从地区层面而言,该类建筑体是按照特定环境1)下的建筑设计原则[1]设计而成的特殊人居环境的一部分。

在关闭之后,这些建筑体通常会获得文化遗产的认证,从而得到制度化的保障。不过,出于经济、政治或环境角度的考虑,对它们的现存状态的评估是不同的:必须进行大幅度改造。对于从矿业转化为后矿业功能的建筑改造项目,建筑设计的任务是采用一种“继往开来”的方式:利用现有条件,同时为了体现变化而增添新的角度。

因此,很多此类改造项目都采用了具有矿业特点的空间主题,如宏大性、地上与地下空间或是大尺度的人工物品,它们激发了人们对空间的想象力和体验,同时也让当代使用者和参观者与过往产生了联结。另外,由于这些主题并非仅与矿业开发相关,它们同时又可以成为一个新项目的空间特点。黑暗既是采矿空间的特点,同时也是夜间活动的特点。通过其多面性的展现,一个建筑空间可以与很多不同的文化领域产生关联。一个新项目的空间仍能唤起人们对过去的空间感受。这些多面性元素和空间特点可以把一个空间置入不同的文化领域背景中,使人们从不同文化角度感受这一空间——或者甚至同时感受到不同的文化氛围。它们增加了空间解读的可能性。安德烈亚斯·莱希纳认为“设计-实践如何体现为媒体-实践、抽象实践、递延尝试、插图、投射、取景、包含或排斥, 决定了连接线的创建”[2]240。在他看来,“类型化设计”是创建这种连接的最常见的方式,可以采用简单的手法,如绘图和图表,但我认为多面性是实现类似设计的另一个工具——少一点结构上的设计,更多地发挥想象力。多面性设计的目标是建立不同方向的连接线。这一方法本身并非目的,但它可以提高空间的社会接受度,使不同的使用者群体找到对空间的认同感[3]。本期收集的项目案例就成功利用了建筑的这一潜能,从而提高了将文化持续形成过程中的不同历史层次组合在一起的可能性。

这种再解读过程某种程度上是实验性的。改造项目中的艺术类项目尤其展现了可以进行再解读的潜在领域的广阔性。有的项目从材料和结构上来看更接近工业和矿业的主题(钢铁、迷宫、狭小的空间,如亨克市的乌托邦城市[4],或是当代和历史上的真实图片),而另一些项目则选择了更出人意料的主题,如由德拉茨创作的大面积的地下水和步入式雕塑作品及废纸雕塑作品,发掘了各个立面可以承载的设计潜力。这些手法是否能应用到所有的项目中对具体的环境进行再解读仍是一个疑问,这也是为什么说它是实验性的。实验性的另一个方面是技术上的应用,如将特殊的几何结构(长竖井)和地理位置(深地下)用于实际用途,作为加热、降温,或食物种植的电池等。

除了以上两种方式,还有第三种,不是从结构或技术上,而是从氛围和空间感上对矿业空间进行再利用。这种方式的改造对建筑的多面性的利用尤其常见。而建筑多面性的潜能和局限性可以从3 个方面进行解读,即宏大性与超大,地上与地下,以及工业物品。

1 宏大性与超大

矿业建筑结构可以是各种尺度。原建筑体的景观设计一直都是2)而且也将继续是改造过程的一部分——通常会在一个比原来更大的尺度上进行。在一个地区内存在几个矿业建筑结构的情况并不少见,因此待改造项目也需要一个超大的景观设计尺度。格哈德·奥尔曾说过“在一片土地景观的衬托下,任何建筑都会显得渺小。即使是最有力量感的建筑或城市设计也仅能带来美学欣赏的愉悦,而不会产生宏大的感觉”[5]26。开放式的采矿场尤其提供了利用这些土地景观的宏大尺度的机会。作为一种有意识的再解读,我们应当更多地将这些曾经的工业遗址看作一种“景观”。通过共同想象力的发展,接受过训练的建筑师们对空间的未来形式进行想象,可以在这一过程中扮演更重要的角色。

This article explores the transformative potential of design strategies from post-mining conversion projects based on architecture's capacity for polyvalence. Architectural mining ensembles relate to a broader cultural context in various ways. In a mining society they make a major contribution to every-day activities and practices including language or dialect like "Pit talk" or call for specific spatial practice, for example through distinct architectural types asking for a specific kind of use like the chain bath, and thus inform a distinct collective memory on a local and regional level. Various regions define their history significantly through the practice of mining, it can inform political supportive practice and opposition, alike and become structural.

The practices of mining gain material expression on various scales: landscape, cities, neighbourhoods,iconic buildings and the unique character of spaces gain their form fundamentally influenced by decisions in the context of mining. Above and below level constructions follow different logics - the existence of raw material in geological formations and the urban layout of an architectural ensemble- which nevertheless relate to each other. During industrialisation accompanied by its societal ambitions, built mining ensembles took an active part in communicating the ideals of work, prosperity and development through their spatial manifestation.On a local scale the ensembles were designed as part of a specific human habitat according to architectural design principles1)of the specific context[1].

After closing, these ensembles can become rewarded with the status of cultural heritage,leading to an institutionalised valorisation. Still, the existing situation is evaluated in a differentiated way due to economic, politic or environmental reasons - things need to be changed strongly. For these reasons the task for an architectural design as part of a transformation from mining to postmining project calls for an "as found" approach:working with the existing, while clearly adding a new perspective supporting the goal of change.

Many projects for the conversion of former ensembles for mining thus show an approach embracing selected spatial topics related to the field of mining, like vastness, above/below ground or large artificial objects, enhancing imaginations and spatial experience from these topics and enabling contemporary users and visitors to relate to the past. As these selected topics do not relate to field of mining only, they can become characteristics of spaces for a new programme simultaneously. Darkness can be a characteristic of mining spaces and of spaces for evening events at the same time. Through its polyvalence one architectural space can relate to various cultural fields. Spaces for a new programme can still evoke spatial experiences from the past. These polyvalent elements and spatial characteristics can inscribe a space into different cultural fields and make this space be experienced as one or the other - or even both at the same time. They increase possibilities of spatial interpretation. Andreas Lechner constitutes"how design-practice horizons can be described as media-practices, as practices of abstraction, efforts of deferral, illustration, projection, framing and in- or exclusion, that create lines of connection."[2]240While he understands "typological designing" as one of the most common procedures to create such relations with simple representations such as sketches and diagrams, I would argue that polyvalence is another tool of achieving something similar - less structureoriented but speculating strongly on imagination instead. The goal is to create lines of connections in different directions. This is not a means to its own end but has been shown to enable societal acceptance of spaces by enhancing the reception among different groups of users[3].

Several of the design projects in this collection operationalise this capacity of architecture enhancing the possibility to synthesise various historical layers in the continuous process of cultural formation.

This process of re-interpretation is partly experimental. Art projects as part of conversion projects in particular, show the large breadth of potential fields of re-interpretation. While some stay closer to an industrial and mining complex of themes though their materiality and layout (iron,maze, narrow spaces such as in Genk, the Utopian City[4]or documentary photography contemporary and historic) others highlight more unexpected topics(volume of under-ground water as walk-in sculpture or waste-paper sculpture by Dratz and Dratz) and explore the extents to which various facets can be potentially carried. If this can still be read as re-interpretation of the specific context remains an open question within every project. This is the reason for their experimental character. A second line of experiment is formed by technology-based approaches that use the specific geometry (long vertical shafts) and location (far below ground) for these pragmatist qualities and think about reusing them as batteries, for heating and cooling or growing food.

Next to these two lines, a third one consists of projects reusing former mining spaces not for their geometric or technical features, but for their atmospheric and spatial qualities. Among these the design-tool of polyvalence is especially common.Three characteristics particularly illustrate the potentials and limitations of polyvalence. It is vastness, above/below and technical artefacts.

1 Vastness, super-large

Mining structures range across all possible sizes. The landscape-design of the original built ensembles has always been of relevance2)and remains relevant for transformation process - often on an even larger scale. Not seldom several mining structures can be found in one region so that the scale of the objects under transformation calls for a super-large-scale landscape design. Gerhard Auer constitutes that "in front of the background of all earth-landscapes everything built will always remain tiny. Even the most powerful of our Building- and City-elevations produce merely esthetic pleasure, but never large emotion (Ergriffenheit)."[5]26Especially open-ground mines offer the possibility to engage with the massive scale of these earth-landscapes.Understanding these former industrial sites as"landscapes" is a conscious act of re-interpretation that has to be carried out by many. It is possible t hrough the development of common imagination- a process in which architects, who are trained to develop their imagination about what spaces could be like in the future, could play an important role.

这一景观尺度为项目的设计从各个层面提供了可能。矿场可以成为自由进入的公园,矿渣堆可以成为供人们远足游览的小山包或是像申格尔贝格那样的社区观望山头,挖掘后的深坑成为可供游泳的湖,火车轨道成为自行车道,而通过火车从大陆各个角落运来的各种植物则可以成为生物活动的主题。从建筑尺度来说,传送带可以变成人行道,大型机器本身如机铲可以成为户外剧院的背景,就像在费罗珀利斯那样。这些改造的实现需要再开发项目和对建筑目的及意义再解读的共同作用,并且通过设计手段将想法具体呈现出来。

2 地上与地下

“人工建造的洞穴与天然洞穴合而为一,后者是封闭式空间的原型,是神的诞生地,居无定所的人类的第一个家。直到今天,所有的地下建筑都与宏大的象征主义有关系。”[6]

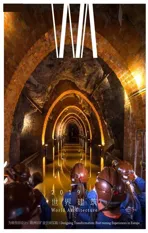

地上还是地下是一个矿业结构最突出的特征。而这里的地下是最能够激发想象力的主题。改造项目中的设计截面——无论是真实的还是经过艺术夸张的——都体现了设计师对这一主题的兴奋,不同的设计以不同的方式对此进行了表现(图1)。

地上与地下的元素的质感和空间排列以及它们的基本空间操作(挖掘或是采集)各不相同。“屋顶的中规中矩可以与地下空间的异想天开并存,这一点几乎毫无疑问。”[6]这种地下空间的“异想天开”需要借助特殊的工具来实现[7]119,如果你不了解这些工具,这一空间就会保持“未知”。这两种空间是无法等同的,地上部分的组成要根据现有的环境或作为建筑体来设计,地下部分则由土地中的原材料的形式来决定。地下部分通常是黑暗的狭窄的挖掘出的空间,地上部分则由精心制作的工业产品组成,并且有覆盖层来保护它们不受天气的影响。异想天开的地下与中规中矩的地上部分毫无疑问会产生强烈的对比,从而激发了今天改造项目的产生。

很多项目试图使这些感受更加强烈和复杂,它们希望通过未来参观者的想象力来延续地上与地下空间的故事,同时又采用一种有效的组织方式使其适用于未来的使用目的。一个例子是51N4E 设计的亨克市C 矿,已经变成了多功能文化中心(图2)。没有了中庭等部分,取而代之的是一个开阔的地面,像一个平台一样将原有的和新加部分连接在一起。一楼本身的层高并不高,通过楼梯或是天花板上的洞与上一层连接。整个空间仍然偏暗——强烈激发了人们对于地下空间的联想。在各种相对较小的区域,宽阔平面上的柱子结构随处可见,如在“Kleine Zaal”厅的休息室,入口及信息区,啤酒店的入口,数个小型可租用会议空间前的酒吧和非正式会谈区域等。采矿空间的黑暗感觉成为了这个新文化中心的连接空间的主要主题。由于该建筑体现在可以用作各种用途,这一中心空间既可以是参观者进入音乐厅的休息室,开会前的聊天场所,也可能是人们前来参观原有的矿场时,进入连续的地上和地下空间前接收到的第一个强烈印象。它将人们对于过往的想象带到了现在(图3、4)。

对于这一主题的建筑再解读的方式层出不穷。如通过色彩(由本特姆-克劳威尔建筑事务所在德国波鸿设计的矿业博物馆中运用的黑色和橙色),空间手法(由让·努维尔在比利时设计的Le Pass 科学公园中的切割和雕刻手法),当然还有循环(由NU 建筑设计事务所在亨克市设计的C 矿中的地上和地下空间,图5)。

3 物品:塔与传送带

还有一些物品清楚地显示了多面性的局限性。大大小小的井塔已经成为矿场改造项目的最具代表性的元素,并成为了各自环境中的标志性建筑物,这也是其最初的设计意图3)。通过极具辨识度的共同特点和形式,它们成为这一地区叙事的标志。在当代设计中,它们有时会被赋予颜色,或者装上一段楼梯成为观景台。这里一览无余的视野使其与地下的黑暗空间形成鲜明的对比。摄影师贝恩德和希拉·贝歇尔在他们的工业建筑摄影集《无名雕塑》中表现了这些物品是如何呈现出它们独特的特点的。“我们在本书中拍摄的物体都具有突出的工具特点,它们的形状是经过计算的结果,它们的开发过程是肉眼可见的。它们都是无名作品,它们的独特性恰恰来自于设计的缺乏。”(图6)[8]时至今日,这些毫无设计可言的物品似乎也无法进行改造设计。很难对这些用于特殊用途的大型物品发挥想象,另作他用。对此类物品而言,双关的空间也很小。类似的例子仅有几个,如吕嫩塔上的科拉尼蛋,他们尝试如何把井塔改造成为类似UFO 降落平台的东西。

1 亨克市的C矿,包括了地面与建筑的设计截面/Section through building and ground below, C-Mine Genk(图片来源/Source: ©51N4E (from archives))

2 C矿的平面方案显示了改造前后的情况/Floor plans showing situation before and after, C-Mine Genk(图片来源/Source:©51N4E)

3.4 亨克市C矿既存建筑与扩建部分外景/Exterior view of existing building and extension, C-Mine Genk

This landscape scale informs design-processes on all levels of a project. Mining structures can become freely accessible parks, slag heaps become small mountains for hiking or guardian neighbourhood hills like Schüngelberg, excavated holes become lakes for swimming, train tracks become paths for bicycle-riding, their specific imported (by trains from all over the continent)biodiversity of plants become a biological event. On an architectural scale conveyor belts can become walkways, large machines themselves, such as power shovels can become the walls of an open-air theatre,such as in Ferropolis. These transformations become possible through a joint effort of re-developing programme and re-interpretation of purpose and meaning and are enforced by design operations materialising this intention.

2 Above and below

"The built cavern converges with the organic cave, archetype of a closed space, birthplace of the gods, first home for the abandoned humans. Until today all subterranean building is afflicted with mighty symbolism."[6]

A mine's relation to the ground or underground is one of its most prominent features. This underground is one of the topics most open to imaginative speculation. Sections - documentary as well as artistically exaggerated - found in the design context of transformation projects show the excitement of the designers with the issue and designs reveal it in diverse ways (Fig. 1).

The qualities and spatial principles of elements above and below ground as well as their basic spatial operation (excavating vs. assembling) vary. "Almost without comment the rationality of the roof can be set across the irrationality of the cellar."[6]This"irrationality" of the cellar requires specific tools to find your way around in[7]119, if you do not know the tools, this space remains an "unknown" open to speculation. The two cannot be navigated equally. The above is organised in relation to an existing context or as ensemble, the below follows the existence of raw materials in the earth. The underground is carved out as a dark and narrow space, the above often consists of elaborate technical objects covered by skins, protecting them from weather. As the irrational "other" to the rational above-ground it quite certainly generates strong images that inform transformation projects for the above today.

Several projects try to make these experiences denser and more complex, relying on the future visitor's imagination to continue the story of the above and below space while effectively organising it in a way suitable for its future purposes. One is the project C-mine in Genk by 51N4E, that has been transformed into a mix-used cultural centre (Fig. 2).Instead of one central hall amidst others there is now one vast ground floor connecting existing and new parts like a platform. The floor itself has a rather low ceiling height with punctual connections to the floor above - through stairs or holes in the ceiling. Still it is rather dark - strongly evoking imaginations about underground spaces. The pillars structure the large surface in various smaller areas, such as the foyer of the "Kleine Zaal", the entrance and information area,the entrance to the Brasserie, a bar and informal meeting areas in front of several small rentable meeting spaces. The darkness of mining spaces becomes the main topic for the connecting space of the new cultural centre. As the whole ensemble houses a variety of programmes today, this central space can be - for the visitor - the foyer of a concert hall, a place to chat before a meeting or the first strong experience in a succession of various spaces above and below ground on a tour through the former mine. It inscribes itself into imaginations of experiences of the past carried on into the present (Fig. 3, 4).

There are endless variations of architecturally re-interpreting this complex of topics. Some are colour (black and orange in the Bergbau-Museum in Bochum by Benthem Crouwel), spatial operations(such as slitting and incision at Le Pass by Jean Nouvel in Belgium) and of course circulation (above and below ground in C-Mine Expeditie by NU Architectuuratelier in Genk, Fig. 5).

3 Objects: towers and conveyor-belts

Another set of objects clearly shows the limitations of polyvalence. Shaft towers as light or massive constructions have become the most emblematic elements of transformed mining areas,serving as landmark objects in their respective contexts- and were designed as such before3). Visible from far they contribute as symbols to a common narrative about the area through their highly recognisable common features and outlines. In contemporary projects they at times become coloured a bit and might serve as Bellevue, when a staircase is added. Offering a panoramic view they serve as spatial counterpoint to the dark and massive underground spaces below.The photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher elaborate in their typology of technical buildings "Anonymous Sculptures", how these objects gain their specific features. "In this book we show objects predominantly instrumental in character, whose shapes are the results of calculation and whose processes of development are optically evident. They are generally objects where anonymity is accepted to be the style. Their peculiarities originate not in spite of, but because of the lack of design." (Fig. 6)[8]These objects, that gain their form because of the lack of design, appear to remain unapproachable for transformative design until today. It appears challenging to imagine these large objects that were designed towards one specific purpose alone as anything else. There is little space for a double-meaning. Few examples exist, like the Colani Egg on the Lünen Tower, as an investigation into how to turn a shaft tower into something like an UFO landing platform.

还有一类具有功能性的建筑元素是轨道和传送带。它们通常呈水平或对角线,可以设置在地下、地面或地上,将煤矿的各部分连接在一起,把材料或火车从一个地方运往另一个地方。在建筑设计中,它们可以变成空中的人行道,行人可以通过其生产程序重新设计货物(比如煤)的运送路径。在埃森,OMA 与海因里希·伯尔主持设计的鲁尔矿业博物馆,通过设置一个长长的通往四层博物馆入口处的扶梯,使对角线传送带得到了重新解读。这段扶梯被设计为带有遮挡的隧道形式,唤起了人们对地下空间的感受,而实际上扶梯是远远高于地面的。

4 结论

对于希望同时实现保护和发展两个目标的后矿业时期项目而言,建筑元素、特点、以及环境的多面性是一个有利的工具。通过这一工具,此类项目的某些元素可以与过去发生关联,而又不会显得过于怀旧,同时新的元素也可以加入进来,为未来创造空间。设计本身也具备了层次丰富的内涵,可以被放入各种语境之中。矿场及其空间特点可以成为设计师丰富的灵感来源,他们可以从地上、地面、地下的不同元素中获得各种各样的设计主题。

在改造过程中,使用者从工人和矿场的管理者变成了更为多样的群体,如曾经的工人、公园内玩耍的儿童、前来参观展览开幕式的情侣、来公园遛狗的人,也可能是新公司的CEO。为了满足这些新的使用者并成为具有自己特点的建筑物,它们的建筑形式必须进行改变。另外,本期专辑中基律纳的项目(见76 页)说明改造并不一定要在矿场关闭之后才进行:随着时间的流逝和使用经验的增加,很可能需要对矿场空间进行改进,从而改变了建筑体的空间结构。在基律纳,设计者从曾经的村庄中选取了某些建筑元素加入到了新场所之中,达到了保护的同时发展的目的,与此同时,设计改变了新场所的结构,使其更宜居。它为曾经的矿场的空间特点和未来发展的再解读提供了一个新的角度。

在本期,我们希望通过一系列案例来说明原矿场建筑的改造可以选择的设计策略,其中建筑多面性就是十分常见的一个。□

5 NU建筑设计事务所在亨克市C矿中设计的地下连廊/Underground connecting corridor, C-Mine Genk Expeditie by NU Architectuuratelier(图片来源/Source: Stijn Bollaert)

6 一个大家族的成员,“井架,1965-1996”/Members of a large family, "Fördertürme, 1965-1996"(图片来源/Source:©Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher; represented by Max Becher)

Another functional set of elements are tracks and conveyor belts. Leading horizontally and diagonally, below, on or above earth, they connect different parts of a colliery, having transported material or lorries from one place to another. Within an architectural design scheme they can become walkways in the air, where pedestrians can reenact the path of, for example coal, through its production process. In the Ruhr Museum in Essen, OMA and Heinrich Böll reinterpret the diagonal conveyor-belts through a long escalator leading to the entrance level of the museum on the 4th floor. The escalator runs through a shaded tunnel evoking the feeling of being below the ground while actually travelling high above.

4 Conclusion

Within the context of post-mining projects and their double-goal to preserve and develop at the same time, the polyvalence of architectural elements, features and situations becomes a useful tool. It makes it possible for certain elements to refer to topics of the past, without falling prey to nostalgy, as others can be easily added and changed to make space for the future. The design is thus enriched with several layers of meaning locating it within several fields of context. Mining sites and their spatial features appear to be a rich source of inspiration to designers who work with the full set of topics found in the context of working with, from and below the earth and it is various components.

In this process of transformation, the addressee shifts from workers and managers of mines to a more diverse group of people including former workers, children playing in parks, couples visiting an exhibition opening, dog-holders in parks and possibly new business CEOs. To reach these new addressees and be recognised as an object with its own rights,architectural form needs to develop. In addition,the project in Kiruna in this issue shows, that transformation does not start only when a mine is closed: throughout time, with the growing experience of all parties involved, improvement and thus change of mining-related spaces can be required. In Kiruna this double-goal is reached be taking certain building elements from the former village and re-locating them to the new site, while clearly changing the layout of the new site to improve living (page 76).This is a perspective contributing to a differentiated reading of the spatial qualities and the future of former mining-sites.

With this issue we hope to compile a variety of examples showing a wide range of design strategies contributing to the transformation of former mining sites amongst which architectural polyvalence is a very common one.□

注释/Notes

1)“在1850年之前,建构与功能性显著塑造了建筑群的形象,到该世纪下半叶,基本的、普遍有效的设计原则得到了测试;它们可以用一些术语进行描述,如加法、幻想、连续、符号、对称、类型、统一、识别。”/"While constructive-functional aspects significantly shaped the image of built ensembles until 1850, basic, universally valid design principles were tested in the second half of that century; they can be described with the terms addition, illusion, series, symbol,symmetry, typification, unification, recognition."[9]34

2) “关于个别的设计元素,所有提到的建筑物之间的开放空间,必须列出景观设计。与功能相关,我们必须在这里顾及到所有的交通方式,如步行、机动车或轨道交通系统,还有其各自的盈余空间。设计理念的代表性在这些盈余空间中变得尤为明显。改善了入口区和行政大楼附近的园艺设计和绿化区,并尽可能地将其发展成庭院。从宫廷封建建筑群中产生的‘入口广场’被引入工业建筑。”/"Regarding the individual design elements,the open spaces between all mentioned buildings, the landscape design has to be listed. Related to function we have to include here all means of transportation,like pedestrian, motor-vehicle or rail-track systems and their respective surplus spaces. Representative of design ambitions became especially visible on these surplus spaces. Horticulturally designed and green areas near entrance zones and administration buildings were improved and, where ever possible, developed as courtyard. The 'cour d'honneur' from courtly-feudal complexes was introduced to industrial architecture."[9]36

3)“作为历史模拟的方尖碑,他们长期宣称着工作、发展和繁荣。”/"As historically modelled obelisks, they proclaimed work, development and prosperity over a long distance."[9]33