考纳斯现代主义的建筑遗产及城市身份

2018-06-19瓦伊达斯皮特路利斯VaidasPetrulis

瓦伊达斯·皮特路利斯/Vaidas Petrulis

黄华青 译/Translated by HUANG Huaqing

2015年4月15日,布鲁塞尔为“1919-1940年的考纳斯”授予欧洲遗产标识,印证了这个立陶宛临时首都在欧洲建筑史的重要地位。同年,考纳斯获颁联合国教科文组织“设计创意之都”称号,两次世界大战期间的建筑遗产也被视为考纳斯获得该称号的重要砝码。这些建筑遗产在考纳斯成功申办2022年“欧洲文化首都”的过程中亦被提及。为该事件策划的文化日程,将包括一项名为“面向未来的现代主义”的项目,将战间建筑遗产置于更广阔的艺术、社会及文化背景中诠释。2017年,考纳斯现代主义建筑被列入联合国教科文组织世界遗产预备目录。显然,现代主义建筑遗产已被推动并采纳为这座城市特征的核心元素之一——它记载着20世纪上半叶的现代欧洲,以及当代城市身份建构过程中新涌现的、可持续的部分,是考纳斯过去到未来的桥梁。有趣的是,将这部分建筑纳入文化遗产的进程出乎意料地拥有一段很长的历史。早在1972年,部分建筑就已被认定为地方性建筑纪念物,这也是现代建筑被纳入文化遗产名录的最早案例之一。

现代主义作为场所的城市性特征

在展开立陶宛现代主义图景之前,有必要短暂回顾相关的政治背景。一战结束后,立陶宛和其他波罗的海国家一起获得独立。然而不久后的1919年,古都维尔纽斯沦陷,立陶宛共和国政府不得不迁往考纳斯——当时的第二大城市。这座曾经的沙俄军事重镇,直至1939年皆作为立陶宛的临时首都。在这段短暂而高强度的时期,考纳斯经历了其历史发展中最重要的阶段。作为国家首都,考纳斯掀起了一波建设热潮,目的是建造一切必须的基础设施:政府机构、博物馆、教育机构(包括一座大学及其他研究机构和学校)、办公楼、宾馆、工业设施、住宅及其他城市基础设施(供水系统、下水系统、新的交通系统、道路和公园)。多文化背景下,考纳斯的建筑景观因不同文化族群的建筑而日益丰富,如教堂、银行和学校等,各具形式表达之特色(1937年城市人口的组成包括61%立陶宛人、25.5%犹太人、3.9%波兰人、3.3%日耳曼人及3.3%俄罗斯人)。1938年,考纳斯吸纳了整个立陶宛城镇建设投资的68%。城市建成区扩大了逾7倍(从1919年的5.57km2到1939年的39.40km2)。

1维陶塔斯大帝军事博物馆,1936年建造,建筑师维拉蒂米拉斯·杜本涅奇斯,卡罗利斯·雷索那斯和卡兹米尔斯·克里斯茨卡迪斯/Vytautas the Great War Museum, architects Vladimiras Dubeneckis, Karolis Reisonas and Kazimieras Kriščiukaitis, built in 1936.(摄影/Photo: Gintaras Česonis)

2考纳斯驻军官员俱乐部总部大楼,1937年建造,建筑师斯塔塞斯·库都卡斯等/Officers Club Ramovė, built in 1937, architects Stasys Kudokas and others. (摄影/Photo:Romualdas Požerskis)

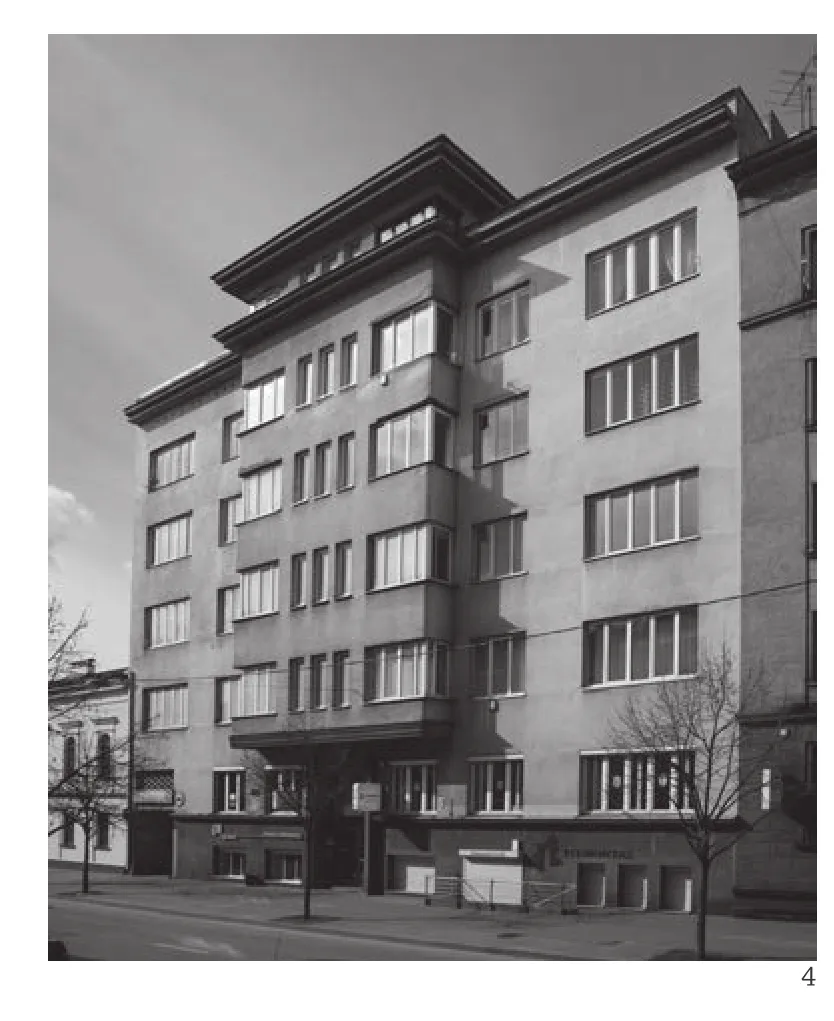

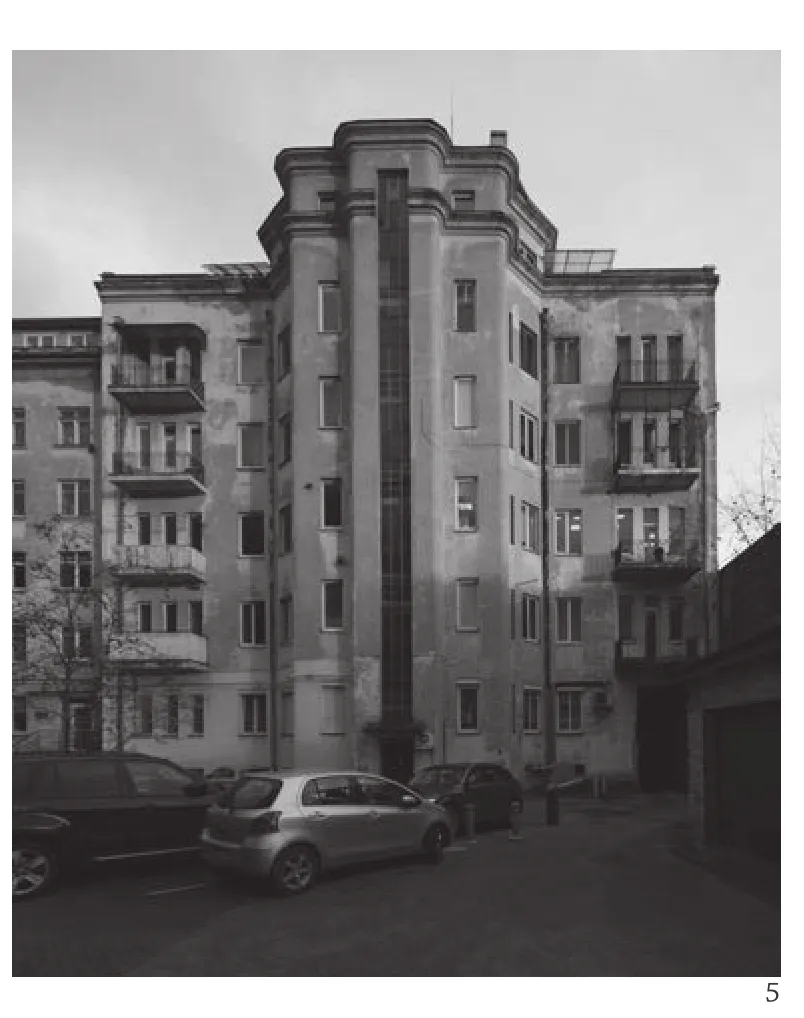

今天的考纳斯,依然保存着逾6000座两次世界大战期间建造的建筑。维陶塔斯大帝军事博物馆(图1)、复活教堂、考纳斯驻军官员俱乐部总部大楼(图2)、立陶宛银行及其他一些标志性建筑,至今依然是城市景观的主宰,塑造着考纳斯的城市标志物之网。此外,临时首都的记忆,亦根植于日常生活环境之中。仍在运行的赞利亚卡涅斯青丘缆车索道和阿勒索塔斯缆车索道(图3)、公寓住宅 (图4、5)、学校、工厂和其他建筑,共同编织起一副多元而丰富的城市骨架。独一无二的地方精神不仅来源于建筑立面,亦包括建成环境中无数细小而原真的细节。在城市街道中漫步,细数数百扇木门,每一扇皆具有个性化的现代设计。室内装饰着原创性的扶手和其他元素。因此,当我们谈到考纳斯这样一座将现代主义内化为地方精神一部分的城市时,也有必要意识到,这是一个多层面的现象,不仅关乎那些标志性建筑,也是一种日常性的习惯。

On 15 April 2015, Brussels conferred the European Heritage Label on "1919-1940 Kaunas"as a testament to the importance of the provisional Lithuanian's capital's phenomenon in the building of Europe. That same year, Kaunas was designated a UNESCO Creative City of Design, with the Interwar heritage acknowledged as a principal criterion for the designation. The architectural legacy was also mentioned in Kaunas'successful bid to be named European Capital of Culture for 2022. The cultural agenda for that year will include a programme entitled'Modernism for the Future', interpreting the Interwar heritage within a broader artistic, social and cultural context. In 2017, Kaunas' modernist architecture was included in the tentative list of UNESCO world heritage sites. Clearly, the modernist heritage has been promoted and adopted as a central element of the city's character – a testament to the modern Europe of the first half of the twentieth century and an emerging and sustainable part of the city's identity, building a bridge from Kaunas' past to its future. It is interesting, that the process of acceptance of this legacy as a cultural heritage has a surprisingly long history. Some buildings were recognised as architectural monuments of local significance as early as 1972 which is one of the earliest inscriptions of modern architecture into cultural heritage list.

Modernism as an urban character of the place

On entering the scene of Lithuanian modernism,it is important to take a short glimpse on the political entourage. Just after the end of WWI,Lithuania, along with the other Baltic countries,gained independence. However, soon after this, in 1919, the historical capital, Vilnius was lost, and the government of the Republic of Lithuania had to move to Kaunas – the second largest city. Previously military town of Tsarist Russia became the temporary capital of the country until 1939. During a short but very intense period, Kaunas lived through the most important phase in its historical development. Its status as a capital city provoked a huge construction boom, aiming to create the entire necessary infrastructure: government institutions, museums,educational institutions (a university, academies and schools), business offices, hotels, industrial premises, housing, and the general infrastructure of the city (water supplies, the sewerage system, a new transport system, roads and parks). The architectural landscape of multicultural Kaunas was enriched by the buildings of various ethnic communities, such as churches, banks and schools, with distinctive forms of expression (in 1937 the population of the city was 61% Lithuanian, 25.5% Jewish, 3.9% Polish, 3.3%German, and 3.3% Russian). In 1938, it attracted 68%of all Lithuanian investment in the construction of towns and cities. The area of the city expanded more than seven times (from 5.57km2in 1919 to 39.40km2in 1939).

More than 6,000 buildings built during the interwar period are still standing in today's Kaunas.Vytautas the Great War Museum (Fig. 1), Resurrection Church, The Officers Club Ramovė (Fig. 2), the Bank of Lithuania and other iconic buildings have survived as the urban dominants and shape the network of urban landmarks of today’s Kaunas. However, reminiscences of the temporary capital are also embedded in the daily life environment. Still-functioning funicular railways in Žaliakalnis and Aleksotas (Fig. 3), residential houses(Fig. 4,5), schools, factories and other objects weave a diverse and manifold urban structure. The unique local spirit is created not only by the façades but also by the small original details of the surroundings. Walking through the streets of the city, we can count hundreds of wooden doors, and each one has its individual modern design. The interiors are decorated with authentic handrails and other elements; therefore,when it comes to Kaunas as a city where modernism is an integral part of the local spirit, it is important to realise that this is a multifaceted phenomenon which is directly related not only to the monuments but also to daily routine.

In essence, the status of the "temporary capital"gave considerable political, cultural and economic impulse to the transformation of Kaunas. It was explicitly recognised by contemporaries who would boast that "no other capital in the Baltic states is so'capitally' prominent like Kaunas <...>." The Lithuanians longing for the old Vilnius haven't even noticed yet that they have already built a new Vilnius”[1]. In a few decades of independence, Kaunas acquired a whole constellation of interwar-period buildings and experienced a large-scale modernisation of the city.This brought Kaunas to a point in the late 1930s when it was already perceived as a city "erasing the traces of the style imposed by the Russians, discovering more and more unique features and acquiring the nature of a modern Western European city"[2].

Modernity as urban manifestation first of all is being defined by functional division of a city into zones, by groups of multi-storey houses, by the principles of free planning, and by certain formal features of architecture that are perhaps most notably expressed in Le Corbusier's five points of modern architecture. The key source of ideological inspiration is overall improvement of hygiene and management of social processes in the city. All of this comprised the common modernist framework, which could be expressed both through individual architectural experiments and larger urban formations depending on specific circumstances. Political aspirations of the new state of Lithuania to build as many "cheap,accurate, hygienic and fireproof dwellings"[3]as possible clearly reflect these tendencies of Modern Movement. However, the actual processes were somewhat different.

3仍在运营的赞利亚卡涅斯青丘缆车索道,1931年建造/Funicular of Green hill (Žaliakalnis) still in operation, built in 1931. (摄影/Photo: Vaidas Petrulis)

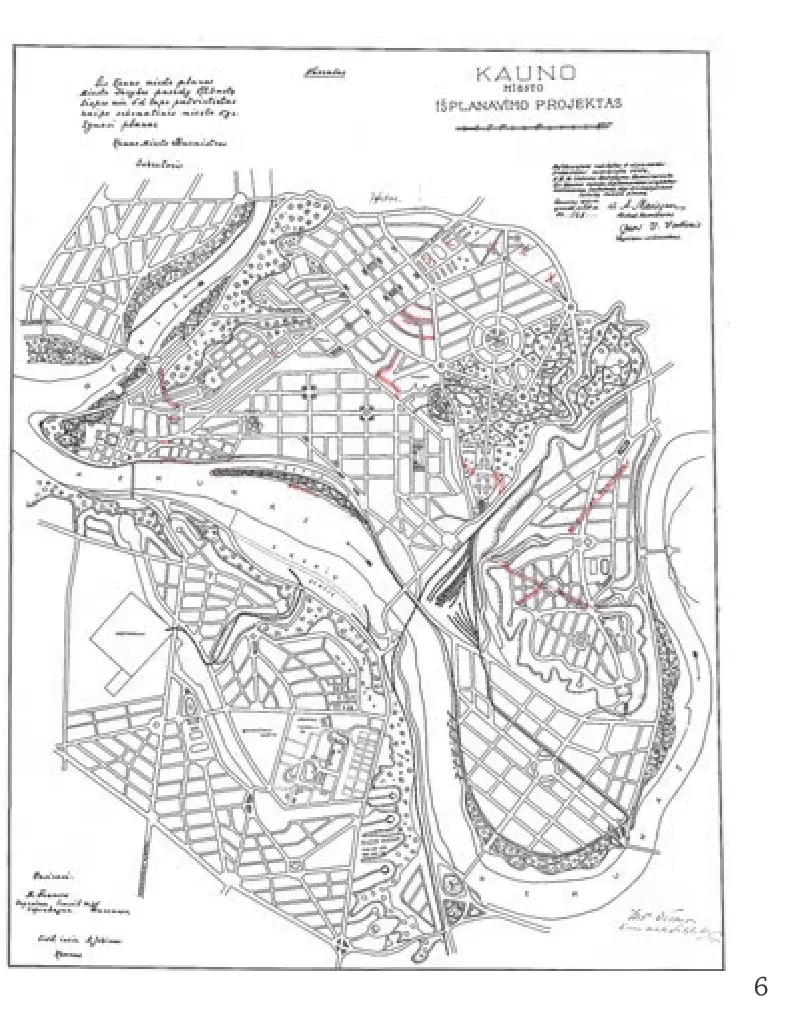

Although a plan for urban development was drawn up in 1923 by Danish architect Peter Marius Fandsen and Lithuanian Antanas Jokimas (Fig.6), most of the construction was carried out not in separate, newly-designed quarters, but the buildings were embedded in the already existing urban structure. Despite a boom in construction,most city offices and residents remained in Tsaristera buildings, which were later renovated, expanded and increased in height. Therefore the life was buzzing in the streets of the constantly changing and modernising Tsarist city. In this way, the modernisation of the environment was characterised not by strict functional zones or dramatic urban redevelopment, but by the consistent urban development with a diverse building, where the aesthetics of the 1930s remain the most characteristic layer and the source of inspiration. Here the interwar architecture dominates not only physically, but also as the most important vector of urban development and the essential part of identity.

根本上说,“临时首都”的地位赋予了考纳斯城市转型极大的政治、文化和经济动力。同代人曾如此直言不讳地宣称,“没有其他任何波罗的海国家首都拥有考纳斯这样杰出的‘首都性’……那些渴望恢复老维尔纽斯的立陶宛人或许还未意识到,他们已然重建了一座新的维尔纽斯。”[1]在独立后几十年间,考纳斯建起了一大批战间建筑,经历了大规模的城市现代化。在1930年代末,考纳斯已发展至这样一个节点,被认为是一座“抹除了俄国强加的风格、愈发独具特色、拥有现代西欧城市特征”的城市[2]。

现代主义作为一种城市宣言,基本定义即表现为城市功能分区、多层住宅区、自由规划原则、以及某些建筑形式上的特征——或许最显而易见的标志就是勒·柯布西耶提出的新建筑五点。其意识形态上的重要源头即城市卫生的整体改观及社会进程的管理。这些理念构筑起现代主义的标准框架,不仅体现在个体建筑实验中,也表现于特定条件下的大范围城市建设。立陶宛这个新国家力图建设尽可能多的“廉价、精准、卫生、防火的居所”[3]的政治目标,明确反映了现代主义运动的某些趋势。然而,实际进程不尽如此。

1923年,丹麦建筑师彼得·马里乌斯·范森和立陶宛建筑师安塔纳斯·乔奇马斯制定了城市发展规划(图6),但大部分建造并不是在另辟新建的街区、而是嵌入业已存在的城市结构之中。尽管经历了建造热潮,但城市中大部分办公和居住功能依然沿用沙俄时期的建筑,这些建筑后来经历了修复、扩建及加高。因此,在这座不断变化及现代化中的沙俄城市的街道上,生活甚为繁忙。如此,城市环境的现代化并不表现为严谨的功能分区或激进的城市重建,而是多样化的持续城市发展建设。其中,1930年代的审美观持续作为最具特征的表现层次和灵感之源。战间建筑不仅在物理环境中占据主导地位,也是城市发展及身份建构中最主要的部分。

4凯米苏奈家族建造的住宅,1931年建造,建筑师维陶塔斯·兰德斯别尔基斯-雅姆卡里尼斯/House built by Chaimsunai family, built in 1931, architect Vytautas Landsbergis-Žemkalnis. (摄影/Photo: Gintaras Česonis)

5凯米苏奈家族建造的住宅背面,1931年建造,建筑师维陶塔斯·兰德斯别尔基斯-雅姆卡里尼斯/Back façade of the house built by Chaimsunai family, built in 1931, architect Vytautas Landsbergis-Žemkalnis. (摄影/Photo: Gintaras Česonis)

6丹麦建筑师彼得·马里乌斯·范森和立陶宛建筑师安塔纳斯·乔奇马斯制定的考纳斯城市发展规划,1923年,部分实现/City development plan prepared for Kaunas by the Danish architect Peter Marius Frandsen and Lithuanian architect Antanas Jokimas.1923. Partly implemented.(图片来源/Source: 立陶宛中央国家档案馆/Lithuanian Central State Archives)

以建筑建构国家身份

从今天的视角回顾20世纪建筑遗产的价值传承,必须注意的是政治因素在其中发挥的作用——不仅体现在城市的直接物质变化,也影响着意识形态背景。在此语境下,最关键的一步就是试图建构国家身份的建筑进程。对所谓“国家风格”的追寻,显然与国家最重要的地缘政治目的之一相关——即强化它在文化领域的地位,由此建立一个强有力的民族国家。这一追求“国家风格”的目标可用当时立陶宛最著名的建筑师之一、也是该项目标的制定者卡罗利斯·雷索那斯的话来阐释:“我们立陶宛人,必须发挥极高的创造力,使我国的建筑屹立于世界之林,以证明我们并非白白活着,并非白白占据这个星球的一部分。”[4]因此,建筑被赋予一项特殊使命——创建独一无二的城市环境,不仅能代表民族国家身份,且彰显出一种完全不同于沙俄传统的建筑形象。

在建筑学领域,大部分“国家风格”的案例皆被视为某种意义上的历史主义,即将传统风格要素替代以装饰性的民间艺术母题(图7)。某些情况下,建筑师的诉求接近于当时典型见于北欧国家的地域主义。这一情境下,立陶宛的地方建筑传统发挥着重要作用,提供了国家建筑身份的可能来源。“我们为何要诉诸国外案例?不如去探索萨莫吉希亚(立陶宛西北地区)的农场,在保持其风格的同时适应更先进、卫生的要求,这样不是更好吗?”[5]——当时其中一本最重要的城市建筑期刊如此发问。

保守民族主义与现代主义建筑的争端往往是通过民间艺术传统的装饰元素来调解的。其中的决定性角色是民间艺术的研究者和支持者,他们确信“国家风格”最合适的基础就是广义上的民间艺术。这类观点集中体现在一批文章中,强调一种立陶宛的独特“艺术感”及装饰化的趋向。正如立陶宛著名艺术家亚当马斯·瓦尔纳斯所宣称的:“装饰性木十字架在民间艺术中的使用,完全是一个立陶宛式现象。它在某种意义上就是我们国家的金字塔。”[6]谈到这个,值得一提的是2011年联合国教科文组织将“立陶宛十字架雕刻及其象征体系”纳入人类口头与非物质遗产名录。

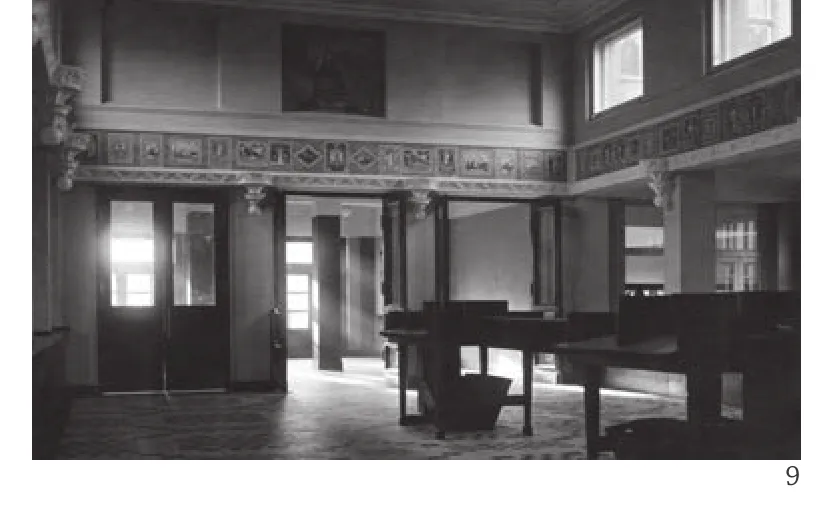

尽管在职业工匠体系中寻找立陶宛精神并不是一个普遍现象,但各种如今可与装饰艺术运动相联系的装饰(不仅是“国家风格”),依然是整个独立期间考纳斯建筑的重要元素。即便在1940年代晚期,新一代建筑师费利克斯·比林斯基依然深信“装饰的形式必须表达整座建筑的意义和使命。一个装饰的特写,就需传达出这座建筑整体的功能。”[7]考纳斯中央邮局就很好地体现了这一愿景,它将现代性与装饰细节中的地方特征相结合(图8、9)。窗框模仿了木雕风格,铺地砖的设计采用了传统织物纹样,室内装饰亦基于民间艺术设计,这一切则与条形长窗、平屋顶等现代主义的标志元素相结合。

现代主义运动的地方诠释

Search for national identity in architecture

Looking back from today's perspective at the inheritance of this 20th century legacy, it is important to notice that political issues had an impact, not only on the direct physical changes of the city, but also on its ideological background. In this context, probably the most important development was of the architectural processes that indicated a search for a national identity. A search for a socalled "national style" was obviously interconnected with one of the most important geopolitical aims of the state – to strengthen its role in the cultural field in such a way as to construct a strong national state. Such an objective for the "national style" can be described in the words of Karolis Reisonas, one of the most famous Lithuanian architects of that time,who formulated the task: "we, Lithuanians, have to show high creativity, and to make our architecture interesting in a global scale; to prove that we live not in vain, not in vain occupy the part of the globe."[4]Therefore, architecture had a special mission –to create a distinctive urban environment which represented the national state and demonstrated an architectural expression which was completely dissimilar to that of the tsarist Russian legacy.

Most of the examples of a "national style" in professional architecture were treated as a kind of historicism in which traditional stylistic elements were replaced by the decorative motifs of folk art(Fig. 7). In some cases, architectural aspirations could be placed somewhere close to those of a kind of regionalism that was typical for Nordic countries of that time. In this context the local architectural traditions of Lithuanian regions played an important role, indicating possible sources for national architectural identity. "Why do we have to seek examples somewhere abroad? Isn’t it better to explore the Samogitian [north-western region of Lithuania]farmsteads instead, and to adapt them to new progressive and hygienic requirements, while preserving their style?"[5]– asks one of the most important journals on urban and architectural issues.

The dispute between conservative nationalism and modern architecture, were often complemented by rhetorics resembling folk traditions. The decisive role in this discussion was played out by folk art researchers and supporters, who had no doubt that the most excellent basis for a "national style" of architecture should be folk art, in a broad sense. Texts emphasising a special Lithuanian "art feeling" and an inclination toward ornamentation were the main foci of this point of view. As the famous Lithuanian artist Adomas Varnas claimed: "the decorative wooden cross, as it was used in our folk art, is an entirely Lithuanian phenomenon. It is a kind of pyramid of our own."[6]In this context, it would be interesting to remember that UNESCO proclaimed in 2011 that Cross Crafting and Symbolism in Lithuania as part of the oral and intangible heritage of humanity.

Although the attempts to search for the Lithuanian spirit in professional masonry construction are not a dominant phenomenon, various decorations(not only in the national-style) that can now be linked to Art Deco, remain an important piece of Kaunas'architecture during the entire period of independence.Even in the late 1930s, the new generation architect,Feliksas Bielinskis, was convinced that "the ornament must, in its form, interpret the meaning and designation of the entire building. Its thumbnail needs to express what is the function of the building in the whole picture"[7]. Kaunas central post office,could be a good illustration of such aspiration to integrate modernity and local character expressed in ornamentation (Fig. 8,9). Window frames imitating wooden carving, floor tiling designed like the ornament of traditional textiles and interior ornament based on folk art was combined with such expressive signs of modernism as wide strip windows and flat roof.

Local interpretations of Modern Movement

Keywords of modernism in Lithuanian architectural theory and practice become dominant in the 1930's, when the younger generation of Lithuanian architects began to return from their studies in European universities (Rome, Prague,Berlin etc.) and brought with them new ideas of how contemporary capital should look. Newspapers and journals began to explain the aesthetics of modernism, and local officials after their visits to Germany, England and Sweden, brought back descriptions of the construction of schools, social housing and other civic infrastructure. One of the first voices, that of Vladas Švipas, a student of the Bauhaus in 1927 writes: "our cities have many historical documents that do not touch our minds anymore because they are past their time. Therefore,as a matter of course, architects who still design using historical styles, have to take responsibility for their preference. These houses are mummies, corpses which will stand publicly for centuries. "[8]

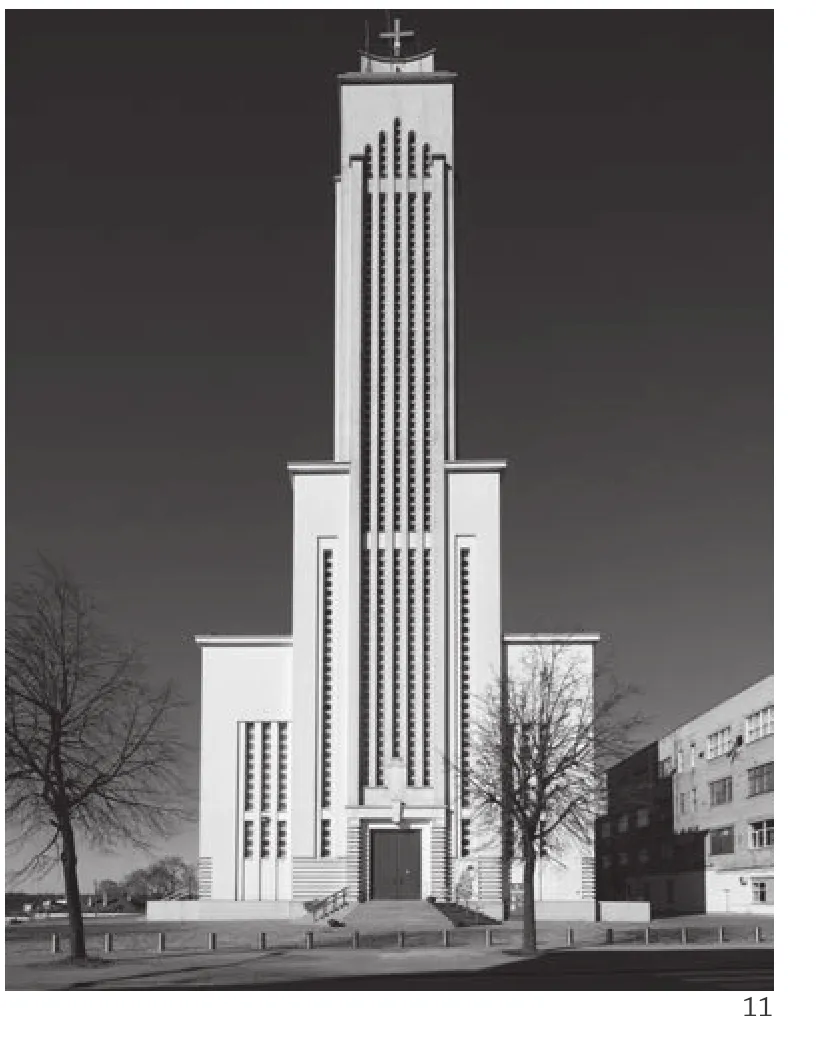

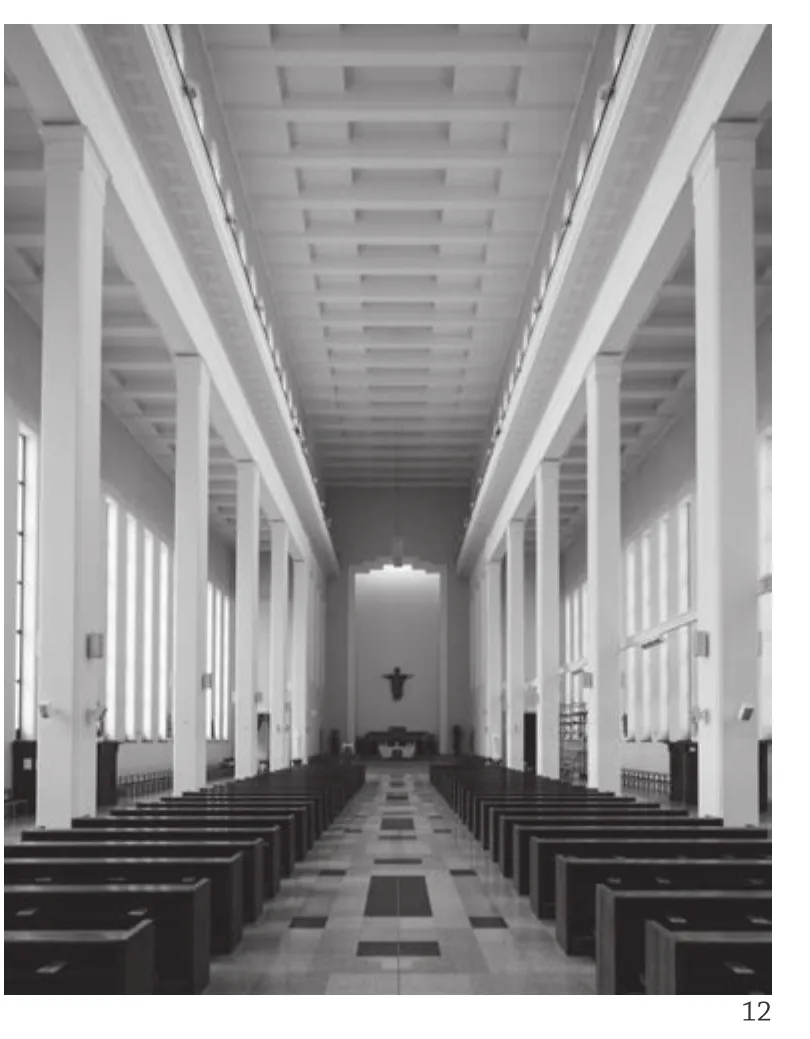

Such theoretical assumptions of the 1930s was transformed into world-renowned modernist aesthetics: the consonance of ribbon windows, flat roofs, geometric volumes and planes. The representative office of "Pienocentras" (a manufacturer of milk products, one of the richest companies in Lithuania at that time) – could be a good example of the emergence of modernist ideas in all areas. In the 1937 Paris International Exposition, which was dedicated to Art and Technology in modern life, building won a prize for its architectural design, and became one of the symbols of modern ideas in Lithuanian architecture of the time (Fig. 10). Another symbolical illustration of architectural processes is the Resurrection Church(Fig. 11,12). After long process of completion and public discussions Karolis Reisonas began to develop his grandiloquent building which was completed and started to serve as a church just in 2004. Rising above the slope horizon surrounding the city the church reminds the concept of Stadtkrone – the City Crown – formulated by the renowned German architect Bruno Taut.

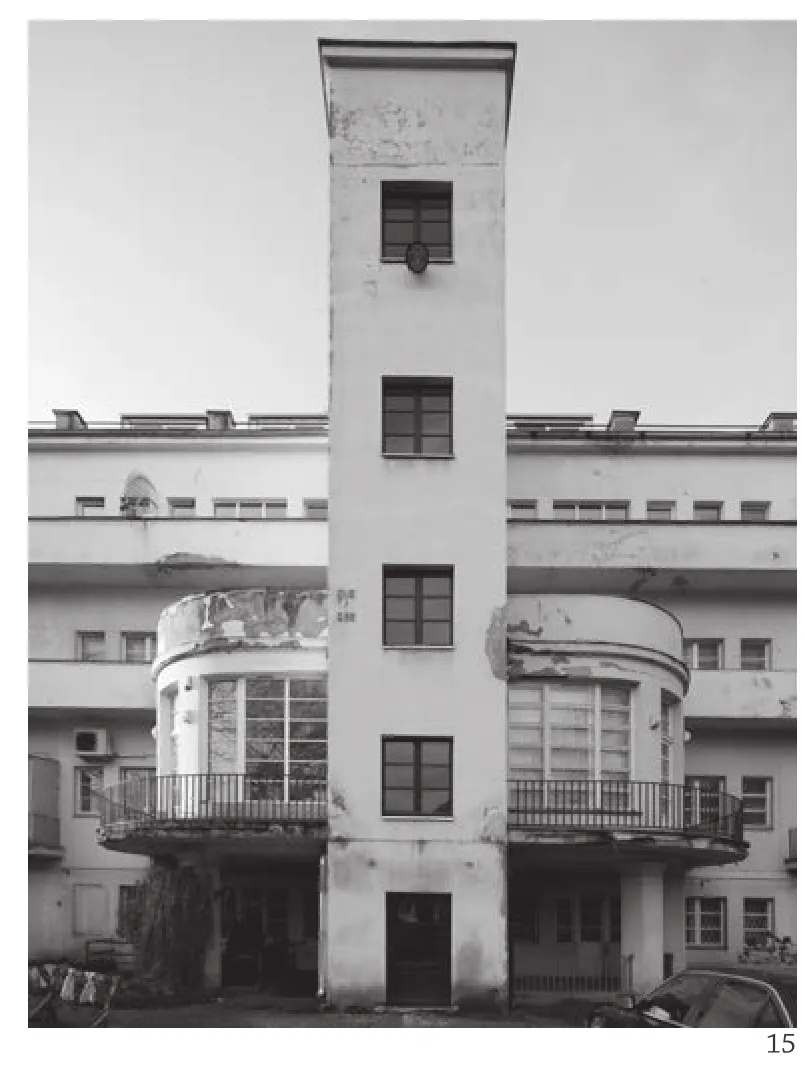

Probably the most numerous part of the Kaunas school of modernism is private housing. Many important examples by such architects as Arnas Funkas (Fig. 13), Bronius Elsbergas (Fig. 14) Jokūbas Peras (Fig. 15), Jonas Kriščiukaitis and others are distinguished by original and expressive forms, which,without a doubt, represents the best achievements of Lithuanian interwar modernism. The modernisation of the housing environment was accompanied by a considerably broad theoretical discourse, with the principles of modern housing being discussed both in print and in the public at large, emphasising efficiency and rationalism. A new concept for housing was first presented in the Lithuanian press by Vladas Švipas.His series of articles, begun in 1927, evolved into a separate publication based on the principles of the Bauhaus, published in 1933 under the title "Urban Residential Homes"[9].

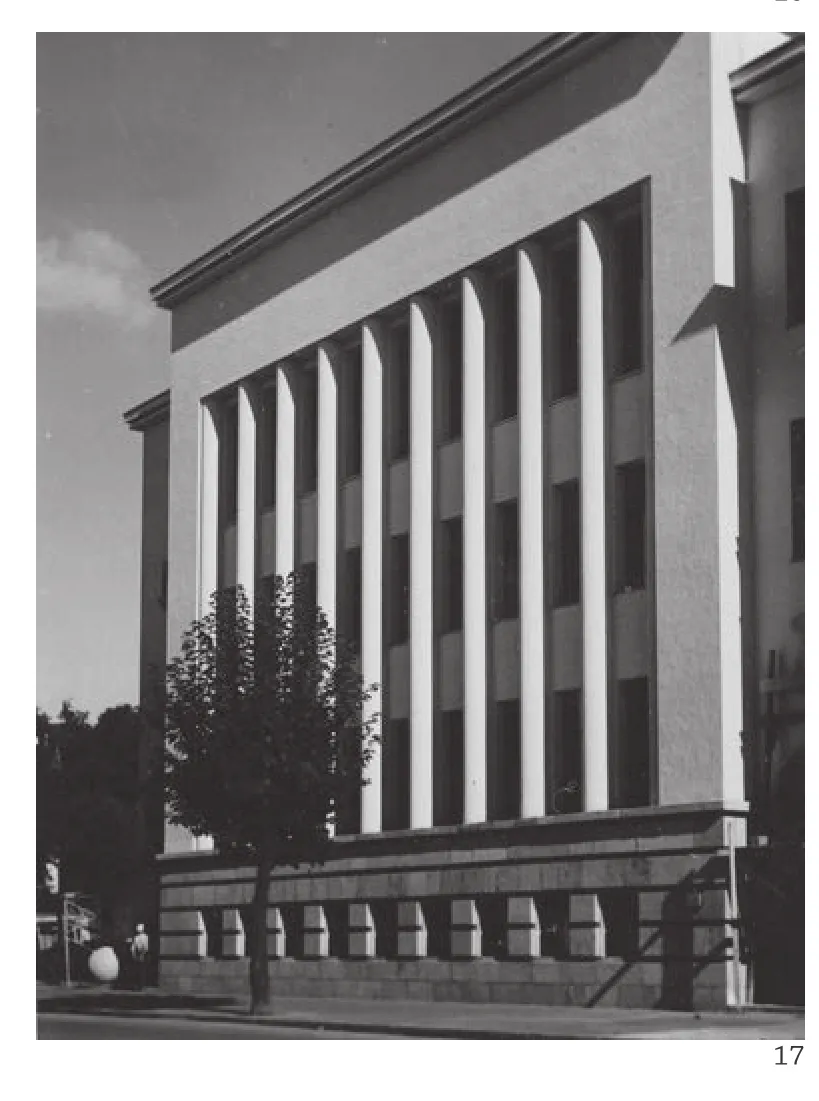

However, when trying to define the characteristic of Kaunas modernism, one has to deal with a phomement much more diverse than simplicity of Modern Movement. One of the elements of the local spirit is the importance of tradition. Although new buildings often used innovative technologies,such as reinforced concrete or glass (Fig. 16), the modernist principles of existential minimalism and standardisation were not adopted in the architecture of Kaunas. Aspirations for modernisation in many cases have been overwhelmed by conservative thoughts. Classical architecture was not forgotten even when advanced technologies were used. For example, Landsbergis-Žemkalnis, who designed the Palace of Physical Education (Fig. 18), wrote in 1932 that he sought "to combine two things and two forms into one building: the classics, the first great pioneer of physical culture (Greece), with our times"[10]. Such a monumental classical rhythm of modern forms describes many buildings of Kaunas built in the 1930s (Fig. 17).

现代主义的关键词在1930年代立陶宛的建筑理论和实践中占据主导,原因是年轻一代立陶宛建筑师在欧洲的大学(罗马、布拉格、柏林等)学成归国,带回关于现代首都形象构设的全新理念。报纸和刊物争相阐释现代主义美学,地方官员在访问德国、英格兰、瑞典后,亦带回关于学校、社会住宅及其他市政基础设施建设的见闻。其中,最早发声的是1927年一位包豪斯学生瓦拉达斯·斯法帕斯:“我们的城市中包含很多历史信息,却无法再触碰我们的心灵,因为它们早已过时。因此,那些仍采取历史风格做设计的建筑师理应为他们的品味负责。这些住宅就是历史的干尸和尸体,竟要在公共眼前继续矗立几个世纪。”[8]

7Tulpė合作公寓楼,1926年建造,建筑师安塔纳斯·马茨贾卡斯/Tulpė Cooperative apartment building, built in 1926,architect Antanas Maciejauskas(图片来源/Source: M. K. 茨瑞利翁尼斯国家艺术博物馆档案/M. K. Čiurlionis National Art Museum Archives)

8考纳斯中央邮局,1931年建造,建筑师菲利萨斯·维茨巴拉斯/Kaunas central post office, built in 1931, architect Feliksas Vizbaras. (摄影/Photo: Gintaras Česonis)

9考纳斯中央邮局内景,1931年建造,建筑师菲利萨斯·维茨巴拉斯/Interior of Kaunas central post office, built in 1931,architect Feliksas Vizbaras. (图片来源/Source: 安塔纳斯·伯尔库斯个人收藏/personal collection of Antanas Burkus)

10"Pienocentras"公司办公楼,1932年建造,建筑师维陶塔斯·兰德斯别尔基斯-雅姆卡里尼斯/Office building of"Pienocentras" company, built in 1932, architect Vytautas Landsbergis-Žemkalnis. (图片来源/Source: 安塔纳斯·伯尔库斯个人收藏/personal collection of Antanas Burkus)

11复活教堂,1931年建造,建筑师卡罗利斯·雷索那斯/Resurrection Church, built from 1931, architect Karolis Reisonas. (摄影/Photo: Gintaras Česonis)

12复活教堂内景,1931年建造,建筑师卡罗利斯·雷索那斯/Resurrection Church, built from 1931, architect Karolis Reisonas. (摄影/Photo: Gintaras Česonis)

13伊利纳艾家庭住宅,1934年建造,建筑师阿尔纳斯·芬卡斯/House for Iljinai family, architect Arnas Funkas, built in 1934. (摄影/Photo: Vaidas Petrulis)

1930年代的理论预设后转化为举世闻名的现代主义美学体系:带形窗、平屋顶、几何体量和平面的交响。“Pienocentras”公司(奶制品生产企业,是当时立陶宛最富有的公司之一)代理办公室是各地涌现的现代主义理念的一个典型代表。在1937年巴黎世博会——那届献给现代生活的艺术与技术的盛会上,这座建筑的设计斩获大奖,也成为当时立陶宛建筑现代理念的象征(图10)。这一建筑进程的另一标志物是复活教堂(图11、12)。经过长时间的竞赛和公共意见征询,卡罗利斯·雷索那斯设计的这座宏伟建筑物直到2004年才建成并投入使用。这座教堂从城市郊区平缓的地平线上拔地而起,使人联想到德国著名建筑师布鲁诺·陶特提出的“城市皇冠”概念。

考纳斯现代主义学派最高产的建筑类型应是私人住宅。由阿尔纳斯·芬卡斯(图13)、布罗尼乌斯·埃尔斯贝格斯(图14)、乔库巴斯 ·波拉斯(图15)、乔纳斯·克里斯茨卡迪斯等建筑师创作的一批重要作品的形式皆具独创性、表现性,无疑代表了立陶宛战间现代主义的最高成就。居住环境的现代化伴随着相当广泛的理论探讨,强调效率和理性的现代住宅原则在理论界和公众领域皆引发讨论。住宅的新理念最早由瓦拉达斯·斯法帕斯刊载于立陶宛媒体。他从1927年开始连载的系列文章最后汇集为一本基于包豪斯原则的出版物,于1933年出版,题为《城市居住的家》[9]。

然而,当我们试图定义考纳斯现代主义的特征,面临的现实远比现代主义运动所倡导的简约要多样得多。地方精神中一个重要的元素是传统。尽管新建筑往往采用增强混凝土或玻璃等新技术(图16),但存在主义式的极少主义和标准化等现代建筑原则并未体现于考纳斯的建筑中。在很多情况下,对现代化的渴求被保守思想所压制。即便在先进技术被广泛使用的年代,古典建筑仍未被遗忘。例如,体育教育馆(图18)的建筑师兰德斯别尔基斯-雅姆卡里尼斯在1932年写道,他试图“将两条头绪、两种形式融入一座建筑:古典——来自物理学先驱的时代(古希腊)——与当代。”[10]这种具有纪念性古典韵律的现代形式,是1930年代很多考纳斯建筑的缩影(图17)。

综上所述,两次世界大战期间立陶宛、尤其是考纳斯的建筑,展现出现代主义运动、“民族风格”诠释及地方建筑品味的有趣融合。尽管考纳斯建造的初衷是重现维尔纽斯这样的历史古都,但乐观主义的居住者们创造出的却是一座由高品质且耐用的建筑构成的切时、现代而风格多样的城市。战间建筑最重大的目标之一——创造一个原创性的立陶宛建筑模式——完全是通过建筑学层面的城市现代化、而非幼稚的民间艺术效仿来实现的。如今,我们不妨把该时期的建筑遗产理解为立陶宛现代主义学派。□

14波洛纳艾和维索卡艾家庭住宅,1933年建造,建筑师布罗尼乌斯·埃尔斯贝格斯/House for Baronai and Visockiai families, architect Bronius Elsbergas, built in 1933. (图片来源/Source: M. K. 茨瑞利翁尼斯国家艺术博物馆档案/M.K. Čiurlionis National Art Museum Archives)

15波斯凡奇斯和科利萨斯家庭住宅,1958年建造,建筑师乔库巴斯·波拉斯/House for Posvianskis and Klisas family,architect Jokūbas Peras, built in 1958. (摄影/Photo:Gintaras Česonis)

16国家储蓄银行(现考纳斯市政局)的屋顶,1940年建造,建筑师阿尔纳斯·芬卡斯/Ceiling in State Savings Bank(now Kaunas City Municipality), architect Arnas Funkas,built in 1940. (摄影/Photo: Vaidas Petrulis)

17工业贸易及手工业大厦,1938年建造,建筑师维陶塔斯·兰德斯别尔基斯-雅姆卡里尼斯/Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Crafts, built in 1938, architect Vytautas Landsbergis-Žemkalnis. (图片来源/Source: M. K. 茨瑞利翁尼斯国家艺术博物馆档案/M. K. Čiurlionis National Art Museum Archives)

18体育教育馆,1934年建造,建筑师维陶塔斯·兰德斯别尔基斯-雅姆卡里尼斯/Palace of Physical Education, built in 1934, architect Vytautas Landsbergis-Žemkalnis. (图片来源/Source: 立陶宛中央国家档案馆摄影文件部/Lithuanian central state archive, photodocuments department)

To sum up, architecture of the interwar period in Lithuania, and especially in Kaunas exhibits an interesting mixture of the Modern Movement,interpretations of so-called "national style", and of local architectural taste. Although Kaunas was built with a hope of restoring the historic capital of Vilnius,the optimistic residents created a contemporary,modern and stylistically diverse city with durable buildings of high quality. One of the most important goals of the interwar architecture – to create an original formula of Lithuanian architecture was completely implemented through modernisation of the city instead of naïve folk art imitations in professional architecture. Now we understand this legacy as a school of Lithuanian modernism. □

参考文献/References

[1]Estų žurnalista apie Kauną [Estonian journalist on Kaunas]. Rytas, 7 February 1935:5.

[2]Kaunas išaugo į modernų miestą. "Polska Zbrojna"atsiliepimas [Kaunas grew into modern city. Opinion by"Polska Zbrojna"], Lietuvos aidas, 22 March 1939:2.

[3]Lietuvos atstatymo komisariato aplinkraštis [Circular of the Lithuanian Reconstruction Commissariat], 1923 m., LCVA, f. 377, ap. 8, b. 4:64.

[4]Karolis Reisonas, Naujos idėjos architektūroje [New ideas in architecture], Savivaldybė, 1933, no. 9:35.

[5]Kaimų ir miestelių pagražinimas [The embellishment of villages and townships], Savivaldybė, 1938, no. 4:98.[6]Adomas Varnas, Lietuvių kryžiai [Lithuanian crosses],Baras, 1925, no. 5:81.

[7]Bielinskis, Feliksas. Architektūros esmė [On Essence of Architecture], Savivaldybė, 1937, nr. 2:61–62[8]Vladas Švipas, Architektūros reikalu [On matters of architecture], Kultūra, 1927, no. 7–8:334.

[9]Vladas Švipas, Miesto gyvenamieji namai [Urban Residential Homes]. Kaunas, 1933.

[10]Landsbergis, Vytautas. Fiziško auklėjimo rūmai [House of physical Education]. Fiziškas auklėjimas, 1931, nr. 2:109–115.