城市山地保护:美国俄亥俄州辛辛那提市案例研究

2018-04-17埃里克鲁索蒂姆阿格内洛张文正胡一可李正

著:(美)埃里克·鲁索 (美)蒂姆·阿格内洛 译:张文正 胡一可 校:李正

辛辛那提是一座山地城市,历史上山体滑坡事故频发。市域范围207km2,其中39km2的土地是坡度不小于20%的山地。

辛辛那提山体的主要基岩地层是科佩组(Kope Formation)和费尔维尤组(Fairview Formation)。这些地层易与水反应,促使页岩迅速崩解。科佩组页岩的破坏会产生一种叫崩积层(colluvium)的物质,因此问题最为严重。辛辛那提地区最常见、最具破坏性的滑坡就是由崩积层形成的。

辛辛那提始建于1788年,1810年后开始迅速发展,至1850年已成为美国第六大城市。在这一发展高峰期中,其大量山地因伐木而变得荒秃,也因建筑、地基及相关用途需求而成为采石场。这些活动加剧了自然山坡的不稳定性问题。随着20世纪辛辛那提不断发展和扩张,大规模的基础设施和私人开发项目不断增加。当这些开发位于崩积层地区时,灾难性的山体滑坡往往随之发生。

20世纪60年代末公众开始认识到辛辛那提坡地问题及其复杂性,致使随后几年进行了一些定量和定性分析。到1976年,这些研究为辛辛那提市对其近一半山地进行开发立法管控提供了基础。

1998年,罗伯特·奥申斯基发表一篇题为《美国的山地开发管控》的论文,该文从历史的角度对山地开发进行了讨论,并探究了不同设计学科如何以不同方式介入这种开发类型。值得注意的是,他的论文最后总结了包括辛辛那提市在内的美国190个地方政府的山地法规和条例。

本文作者将从历史和年代顺序的角度更深入地探讨辛辛那提的山地法规。首先,总体介绍研究区域,举例说明城市的自然地理和地质条件。然后,追溯辛辛那提的人类定居历史,以及人类活动对山地的破坏性影响,特别是在城市人口经过快速增长的初期阶段。这些地理、地质和历史信息大都引自那些保存于山地信托基金会办公室的博士论文。在这一历史概述所提供的背景下,笔者继续记述一种行动主义的出现,这种行动主义导致建立市政山地法规的颁布以及山地信托基金会这一非营利性山地保护组织的创建。这些信息大多来自山地信托基金会过去50年来所存档的报纸和杂志文章。最后,总结了辛辛那提在山地法规方面所取得的进步及其尚待改进之处。这些结论是基于1976年以来山地信托基金会与辛辛那提市及其山地区划法规的专业性互动的轶事经验。

1 研究区域

辛辛那提市是美国俄亥俄州的一个城市,人口301 301[1]。从美国东海岸到辛辛那提市的距离,占到整个美国东西海岸距离的1/3。该市的中央商务区建于一个约10.05km2的半圆形高地上,高出河漫滩,地势安全[2]。

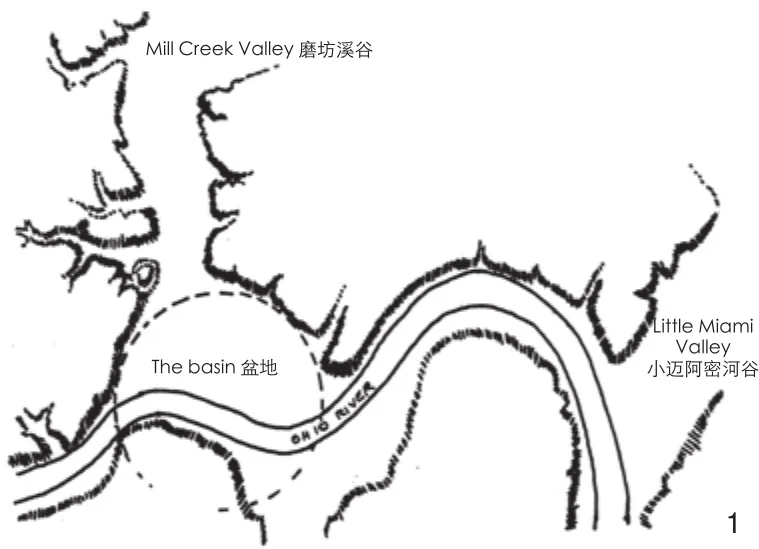

辛辛那提核心区域(或市中心)通常被称为盆地(图1),三面为高出盆底70多m的陡坡(图2)。一些次级山谷——包括那些属于米尔溪和鹿溪流域的山谷——分别从西部和东部切割盆地山坡,其他次级山谷则直接切入俄亥俄河谷。这些山谷在通往高地的路上形成更小和更浅的沟谷,在盆地上方形成一条连续的地平线。

在辛辛那提的207km2土地中,39km2为坡度不小于20%的山地[3]。一般来说,这些坡地上覆盖着次生和三生林,其间零星散布着一些已开发区域,在春季和夏季形成一幅绿色马赛克图案。

辛辛那提核心区对面的俄亥俄河南岸地区主要由肯塔基州(与俄亥俄州南部交界)的科文顿市和纽波特市组成。 这些城市位于另一个较小的高位盆地上,盆地之上的坡地同样陡峭。该地区与辛辛那提市和俄亥俄州西南部具有相似的地质条件和山体滑坡易发性。本文作者将聚焦辛辛那提市。

辛辛那提的坡地景观是大陆冰川作用的结果,大约在200万年前开始。最后一次冰川活动于1900年前在辛辛那提北部开始消退[4]。

1 辛辛那提盆地的示意图Schematic of Cincinnati basin

辛辛那提坡地的主要基岩地层是科佩组和费尔维尤组。 科佩组由约80%的页岩和20%的石灰岩组成。费尔维尤组位于科佩组上方,由约50%的页岩和50%的石灰岩组成。在盆地附近,这些地层分布于海拔400~850英尺(约121~260m)处。辛辛那提大学地质学教授保罗·波特认为,“辛辛那提地区的所有页岩都容易与水发生强烈反应,因为它们很容易迅速分解(或崩解)”。科佩组地层问题最严重,因为它主要是由崩积层生成的基岩单元[5]。崩积层是一个地质学术语,指主要由黏土颗粒组成的土壤,由科佩组页岩风化分解而来,在基岩上或沿着山谷两侧发育。辛辛那提地区最常见和最具破坏性的滑坡即发生在崩积层[5]。

除崩积层外,冰川沉积物遍布辛辛那提地区,包括不稳定的湖黏土。这些黏土是冰川融水形成湖泊后的残余沉积物。湖黏土的问题在于其也非常容易发生滑坡[6]。辛辛那提的滑坡通常移动较慢,不同于加利福尼亚州等美国其他地区的迅速而剧烈的滑坡可以转瞬夺去生命。这些滑坡往往每年仅移动几厘米,但随着时间的推移,它们带来的结构损害和经济损失依然不可小觑。

2 早期土地利用与定居的影响

在美国独立战争(1775——1783年)之后,新成立的联邦政府决定将阿勒格尼山脉以西土地用于定居[2]。这些土地包括现在的俄亥俄州西南部和肯塔基州北部,拥有原始木材、肥沃的土壤、淡水和丰富的野生动物资源等丰富的资源。

欧洲移民后裔自1788年开始在现在的辛辛那提定居。他们先沿俄亥俄河建立了3个不同的营地,最终选择在海拔较高且相对开阔的盆地区域定居[2]。由于与迈阿密、肖尼、威扬多特和特拉华等坚决捍卫家园的土著部落发生持续冲突,人口增长缓慢[2]。

2 从普莱斯山向东远眺辛辛那提市的盆地。注意那些环绕盆地背景的山坡,其形成一条几乎相同的地平线View of Cincinnati basin looking east from Price Hill. Note hillsides in the background that encircle the basin and form a nearly uniform horizon line

在1794年和1811年美国政府对美国土著民的决定性战役胜利之后,辛辛那提的人口开始迅速增长[2]。辛辛那提位于一条主要内陆河畔,既是进入美国西部边疆的一个门户,也是那些希望在新土地上开始新生活的人们的一个目的地。 美国人口普查数据显示,辛辛那提的人口在1810——1850年间每10年至少增加1倍。至1850年,它已成为美国第六大城市,人口数量达115 435[2]。

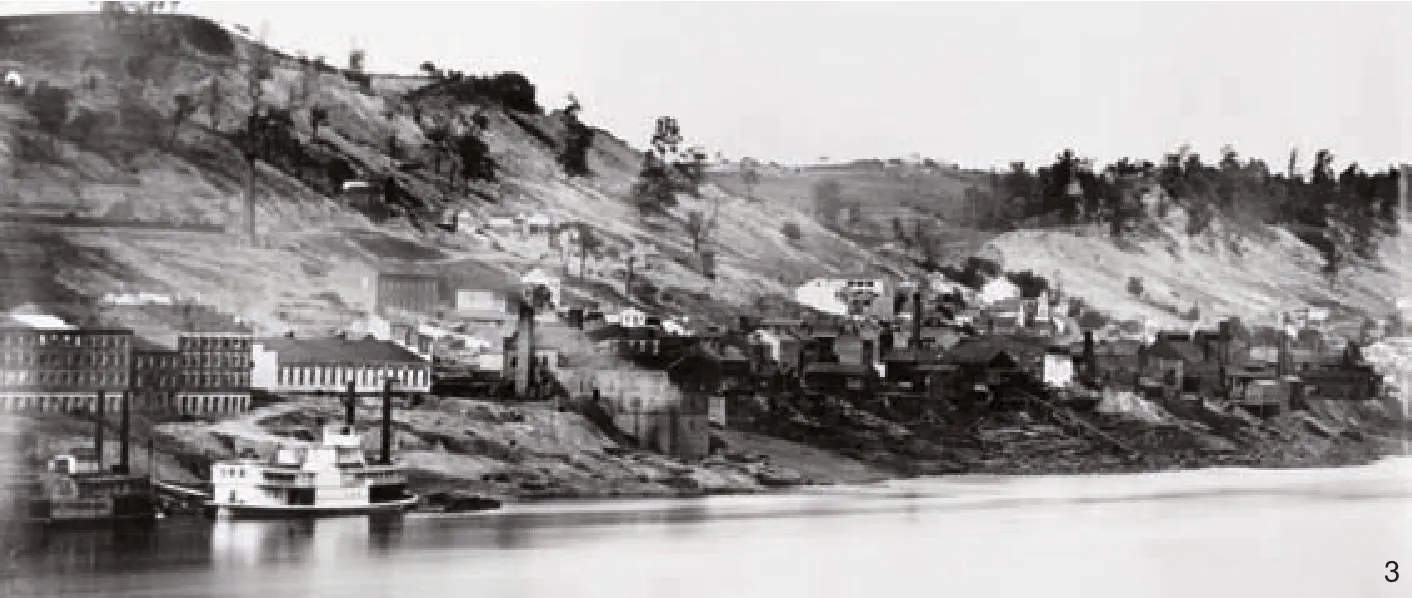

人口的迅速增长导致对自然资源特别是木材的需求增加。著名医生及自然主义者丹尼尔·德雷克于1815年指出,木材是“主要燃料且来自周围山丘”[7]。此外山地还被用于农业生产,被犁耕以种植农作物,以及被开垦为梯田以种植葡萄[8]。19世纪辛辛那提的山坡上普遍进行放牧活动[9],这可能是造成植被破坏、梯田形成和水土流失加剧的一个因素。辛辛那提和汉密尔顿公共图书馆的主要分馆收藏了由丰泰纳和波特拍摄于19世纪中期的一系列全景式银版照片,这些照片描绘了辛辛那提山地植被遭到改变和伐毁的场景(图3)。

采石是严重影响山地的另一个产业。石灰石是建筑、地基和挡土墙的首选建材[10],也是石灰砂浆、路基和路面的重要材料[11-12]。除了河床采石场,山地采石场是辛辛那提石灰岩的另一个主要来源[11-12]。山地采石场的最理想位置是费尔维尤组上部50英尺(约15m)处[13],这一地层位于山地谷壁的最上部。1826年德雷克将辛辛那提山顶附近的区域描述为“裸露的垂直悬崖”,在费尔维尤组石灰岩的上部因采石活动而变成垂直地形(图4)。包括砍伐森林和采石活动在内的早期土地利用导致辛辛那提发生大规模的山体滑坡[14-15]。

在19世纪最后1/3的时间里,斜坡铁路、有轨电车和铁路线的出现使得大量当地人能够“逃离肮脏而拥挤的盆地”而住在远离工厂的区域[2]。从19世纪70年代开始,共5条斜坡铁路在市中心盆地周边的各山地上建成(图4)。这些斜坡铁路装载着旅客、建材和货物穿过陡坡,其规模是马车所无法匹敌的。诸如亚当斯山、奥本山、克利夫顿山和普莱斯山这样的新社区得以在山地周围乃至以外地区发展起来。

这些斜坡铁路为辛辛那提首次提供了来往于盆地和山坡之间的廉价便捷通道,从而革命性地带动了城市发展[2]。这也使该市土地面积得以最大限度地扩张,在1869——1918年间,辛辛那提向外扩张和吞并了超过168km2的土地,整个城市的人口接近50万[2]。斜坡铁路的建造和持续运营也导致了山体滑坡。

在20世纪20年代末,一条被称为哥伦比亚林荫大道的现代公路开始施工。哥伦比亚林荫大道是美国州际公路系统的先驱,其目的是建立一条连接市中心和东部郊区的汽车导向型交通走廊,大量的工程和土方作业需要沿着一片平行于俄亥俄河的陡峭盘旋山地的中部展开。这条公路所造成的地质影响一直持续到21世纪,下文将就此进行讨论。

3 人类与山地互动的影响

早在人类到来之前,大辛辛那提地区就发生过大规模山体滑坡[16]。然而,1788年辛辛那提城市建成以来的高强度土地利用加剧了山地的不稳定性。历史证据表明,森林砍伐、农业耕作、采石和放牧活动都对该地区山地的自然坡度和排水模式产生了负面影响。19世纪上半叶以来滑坡一直都是困扰辛辛那提的问题,而一些深层滑坡(超过1.5m深度)可能未被发现[14-15]。

随着城市的发展和成熟,大型基础设施和私人开发项目也在增加,其中许多涉及山地区域。当这些开发位于脆弱的基质区域(崩积层)时,结果往往是灾难性的。以下概要重点介绍其中一些灾难性事件[14-15]。

·1926年,市中心盆地以西发生一起大面积基础坍塌型山体滑坡,原因是坡脚挖方[17]。该斜坡底部的挖方达到600m宽和12m高,导致其上450多m山坡发生移位,并导致梯形切割面以下的地面被扰动而隆起约4.5m。该滑坡的总体表面积超过350 000m2。

·1930年,在哥伦比亚林荫大道的施工时发生了一起重大滑坡,原因是在拓宽狭窄的哥伦比亚路时开挖了路面以上的山地,并将土方倾倒下去。哥伦比亚林荫大道自竣工以来持续发生山体滑坡。它是一条主干道,每天承载成千上万的车辆。每年林荫大道上方过陡的斜坡都会冲破挡土墙。这些山体滑坡有时严重到每次足以使部分(或全部)的东西向交通要道关闭数小时(图5)。

·1972年,一起大规模山地滑坡在盆地正北方的克利夫顿高地形成了一个55m长、9m高的悬崖,起因是几年前建造的一座公寓楼及毗邻的停车场(图6)。大约12个公寓单元、1座加油站以及滑坡下方工厂的相关人员被撤离[18]。至今,从卡鲁塔楼——市中心最高的建筑之一——还可以看到该滑坡的左右两侧。

·1973年,俄亥俄州交通部在亚当斯山山脚下进行了2m高的垂直开挖,为跨俄亥俄河的新471号州际公路大桥建造进出坡道。当天然气管道和水管开始破裂时,该市下令让该山地住区的15家住户永久撤离[19]。7年后,政府官员批准了一项解决方案,即建造一面长390m、深30m的混凝土墙,使用一种钻墩和电缆系统来挡住巨大的山坡。在这堵墙的施工期间,打桩引起的震荡引发了另一起滑坡,导致大约30家住户永久撤离[19]。当该混凝土墙在8年后的1981年竣工时,其耗资高达2 220万美元[20]。当时,这是美国有史以来损失最严重的山体滑坡之一。

每年仅因山地滑坡破坏公共基础设施而付出的代价就已惊人。由辛辛那提大学师生进行的一项滑坡修复研究发现,辛辛那提市各街道紧急维修的直接费用约为每年50万美元[5]。1987年辛辛那提各街道滑坡破坏的延期维修费用约为1 850万美元[21]。这些调查结果是一个更大范围特别任务的组成部分,该任务于1985年启动,旨在调查并主动解决辛辛那提基础设施的维护和保养问题,下文将对此进行更全面的讨论。值得注意的是,这些数字不包括城市内私人财产因滑坡而造成的损失,后者的损失数字更难量化和获取。斜坡不稳定性及其对辛辛那提山地住宅建设的破坏是普遍存在的问题。

4 激进主义、行动与山地信托基金会的建立

1967年5月4日是辛辛那提实施山地保护措施历程上的一个里程碑。在这一天,一个“山地论坛”在位于亚当斯山的辛辛那提艺术博物馆召开。之所以选中此地可能是因为其如画的山顶位置,并能俯瞰市中心盆地的景色。

该论坛的一份宣传单敦促感兴趣的公民参与“讨论辛辛那提山地的未来”。论坛的演讲者包括辛辛那提市各政府部门负责人,以及代表住房、开发、艺术和环境等多方面的专业人士。这个为期一日的活动产生了各种行动步骤,包括对该市山地进行定量和定性分析的计划。

1969年,辛辛那提规划委员会发布《山地研究》,该报告针对于该市范围内的23处山地,这些山地具有自然群落分隔、植被绿化背景和住宅区中心等特征[22]。3年后,辛辛那提规划委员会聘请理查德·A·加德纳公司编制了《辛辛那提山地——推荐的设计流程和行动计划》。这份报告的主题包括一个未来几年需要遵循的循序渐进过程,以确保合适的山地开发[22]。报告中有一项值得注意的建议,即成立一个非营利性组织来负责征购尚未开发的山地,并在该土地被出售再开发时进行设计控制[23]。

从20世纪60年代末至70年代,科尔曼教皇成为城市和社区圈子中知名的艺术、环境和城市问题倡导者。他是1967年山地论坛的9位发言人之一,还曾担任辛辛那提规划委员会的山地咨询委员会主席,1971年成立了非营利性的以提高城市生活质量为使命的辛辛那提研究所。

在科尔曼教皇的领导下,辛辛那提研究所与辛辛那提规划委员会密切合作,开展山地研究和保护工作。1973年,国家艺术基金会在“城市边缘”计划下授予辛辛那提研究所40 000美元,以帮助后者保护和改善该市的山地。辛辛那提是367个申请者中获得这项拨款资助的37个城市之一[3]。该拨款部分被用于分析研究以确定辛辛那提的山地特征及制定设计导则。

辛辛那提研究所聘请了法律顾问来制定临时管控措施,并为处理该问题的最终土地分区法规起草文件。拨款被用于采访100位辛辛那提市民,记录他们对该市山地的印象。这些访谈的记录提供了关于山地对当地居民心理健康的积极影响的宝贵认识[24]。剩余拨款则被用于建立一个非营利的山地组织,正如加德纳公司在1971年研究报告中所建议的。这个非营利组织成立于1976年10月,名为“山地信托基金会”。

辛辛那提研究所在1973年和1974年组织和总结了多次山地研究。1975年,与旧金山规划师冈本签订合约,进行最终的实地调查、摄影记录和其他山地分析。这项工作以一份1975年底为辛辛那提城市规划委员会准备的题为《辛辛那提山地——开发导则》的创新性报告而宣告结束。该文件提供了关于地质、土壤特征、植被类型、公私用途、视觉特征和其他城市规划因素的详细研究。随着山地信托基金会开始发展,辛辛那提研究所在20世纪70年代末停止运营。

5 山地保护措施建立

1976年6月,辛辛那提规划委员会正式采纳了一份题为《辛辛那提山地——开发指南》的文件。当时,该规划委员会正在敲定被称之为“环境质量区”(EQD)的特殊规章。EQD是一种叠加分区,旨在“协助土地和建筑开发以使其与环境和谐,并保护一些特定地点的城市环境品质,这些地点具有重要公共价值,以及易被那些传统分区和建筑规章所允许的开发活动所破坏的环境特征”[25]。EQD共分4类,包括公共投资区、城市设计、社区振兴和山地。

然而,正是这些特殊叠加分区的山地成分才是一开始制定环境治理区的背后驱动力。该市意识到其山地易遭滑坡的特性,并认为有必要通过山地法规来防止这一问题因无序开发而加剧。1969年《山地研究》所识别的23处山地均被划入了“环境质量——山地区”(EQ-HS)。《山地研究》认为这些坡地极为重要,因为其至少50%面积位于23处山地中的1处或多处之内,且包含以下6个要素中的至少4个:1)大于等于20%的坡度;2)科佩组的存在;3)显眼的山地(可从辛辛那提山地系统内某被指定山地的下方山谷中的公共街道上看到);4)拥有观赏某主要溪流或山谷视野的山地;5)作为社区分隔或社区边界的山坡(已在城市规划委员会批准的某社区规划中被识别);6)树木茂密的山地。

尽管经过多年的努力,EQ-HS所划定的23处山地中仅有不足一半获得了城市土地分区立法。每个社区理事会有责任向市议会提出建议,在其社区内采纳已有的EQ-HS。也许是因为缺乏紧迫感,其他社区未能成功采纳EQ-HS。尽管如此,自1976年以来,包括东普莱斯山、奥本山、克利夫顿山和亚当斯山在内的所有盆地区域的山地社区均通过立法采纳了EQ-HS分区。这些山地社区不仅可以俯瞰市中心盆地,他们本身也成为从盆地底部仰视所看到的引人注目的自然地标(图7)。具有讽刺意味的是,在该市开始采取措施积极管理其山地的同时,20世纪70年代辛辛那提地区的滑坡人均损失创下了美国城市区的历史最高纪录[26]。

在20世纪80年代中期,辛辛那提商界和学界领袖组成一个委员会,就改善和保护城市资产的方法献计献策,包括为改进建议提供资金的措施。1987年,在当时宝洁公司董事长兼首席执行官约翰·斯梅尔主持下,该委员会完成了《斯梅尔基础设施委员会报告》。该报告列出的100多项建议中有4项与山地相关,其中最为重要者于1989年被辛辛那提市采纳。

第一个建议是提供资金为该市的所有挡土墙编制清册,包括为该清册的更新而分配未来预算。截至2018年,该市范围内约80km长的挡土墙被记录[27]。这一初步努力的成功发展为《挡土墙和滑坡稳定计划》,该计划的目标是“使所有现有挡土墙处于良好状态,并稳定那些影响城市道路的滑坡”[27]。每面城市挡土墙每6年检查一次,这有助于确定某墙是否需要被替换或修复。该计划的资金每年都经过精心分配,重点是先解决最迫切的需求以防止对城市街道和设施造成严重破坏。值得注意的是,该计划并没有减少该市挡土墙上方或下方的滑坡,而仅仅减缓和减轻了滑坡对距离城市街道和公共设施最近处的直接影响。

3 1848年亚当斯山的毁林区域(7号底片)。俄亥俄河位于前景Deforested hillsides - Mt. Adams, 1848 (Plate No. 7). Ohio River is in the foreground

4 1900年前后的贝尔维尤住宅及斜坡(克利夫顿)。注意建筑群下面的因采石活动而形成的高耸悬崖Bellevue House and incline (Clifton) circa 1900. Note the high vertical cliffs below the complex from quarrying activity

第二个得到实施的建议是在该市交通和工程部内设立一个地质技术处。自1989年以来,该市一直雇佣1名受过工程培训的全职工程地质学家和1名全职地质技术工程师。这2个职位的主要职责是在公共通行权及该市所控制的其他财产范围内提供关于滑坡稳定和防治的地质技术评价。地质技术人员还与城市规划部门、建筑和检查部门等所有其他市政府职能部门交换意见。具体来说,他们在建筑方案检查员对位于滑坡敏感地区的项目进行审查时提供协助。《斯梅尔基础设施委员会报告》原本建议在地质技术办公室的两名雇员中包含1名地质学家,因为地质学家更易发现先前存在的滑坡状况,并参考那些易被忽略或遗忘的当地滑坡历史记录。就其本身而言,山地信托基金会在这个问题上发挥了重要的核实作用,为历史滑坡、山地利用及倡导相关记忆提供了一份机构记录。

6 山地信托基金会确立其山地倡导角色

当1976年山地信托基金会成立时,人们就清楚该基金会缺乏资金来实施其纲领中的一个目标,即成为一个购买并持有山地的土地银行,然后以负责任的方式监督其未来发展。于是该基金会只能强调其纲领中的其他目标:1)研究和教育; 2)土地资源保护;3)倡导负责任的土地利用。

在1987年《斯梅尔基础设施委员会报告》和1988年山地信托基金会主办名为“美元和理性——辛辛那提和汉密尔顿县山体滑坡的经济影响”的会议之后,该基金会在1989年启动了一项雄心勃勃的研究工作。该研究于1991年完成,成果为《大辛辛那提的山地保护策略》。该研究的第二卷包括详细的山地分析,以及一系列关于视觉质量、滑坡易发性、环境生态质量、易遭开发性、视觉和环境敏感性、需优先保护的坡地等问题的地图。基于第2卷的信息和分析,该研究的第3卷包含了145条针对山地开发的导则。第1卷包括1篇关于该研究的简短介绍。

这项研究的300多份复印本已经按成本价出售给美国和加拿大的各个市政规划部门和私人规划设计公司。山地信托基金会在1992年举办一个研讨会,与辛辛那提市区内的地方政府进行沟通,建议他们采用山地开发导则。最终,辛辛那提市和其他地方政府均未采纳这些导则。不过,1997年辛辛那提市认可了山地信托基金会在山地和滑坡问题上的专业声誉,开始向基金会通报其EQ-HS区内的山地开发建议,并邀请其就这些建议公开发表评论。在1997——2003年间,山地信托基金会就这些EQ-HS区内的至少28项开发建议提供了书面或口头证言。虽然基金会并不反对开发,它会在必要时与当地居民合作,揭露那些其认为会对周边环境造成负面影响的方案,或指出任何缺乏工程远见的方案。山地信托基金会之所以能扮演这种角色,是因为其受托人、技术顾问和执行董事所具有的专业知识。

2004年初,辛辛那提市公布了一项新的分区法规。所有EQ-HS分区都被新的类别取代,即“山地叠加区”(HOD)。之前的EQ-HS仅有不到一半被编入法规,而新的HOD可被应用于全市范围。一个地产被划作HOD的依据是其任何部分的坡度等于或大于20%,或其任何部分在1980年由索尔斯和达尔林普尔为该市绘制的《滑坡易发性图》中被指定为中高或高滑坡易发。1969年的《山地研究》和1975年的《辛辛那提山地开发导则》均作为支持文件被纳入HOD分区中。

HOD分区包括一系列基础开发要求,根据这些要求,必须满足任何建筑许可证的请求。《辛辛那提区划法》第1433-19节列出了这些要求:1)任何新建筑或旧建筑改造必须限制在最大建筑围护结构之内(相关参数由城市定义);2)山顶上的建筑物高度必须长于宽度,以强调垂直维度;3)位于山脊之下或之上的建筑必须在进深和面宽上采用交错或阶梯式布局,以符合地形;4)屋顶公用设施和机械设备要么完全不用,要么采取屏蔽和声控措施;5) 建筑竣工后剩下的所有透水面必须用乔木、灌木、草本或其他地被植物进行绿化,以稳固坡地和减少过多径流;6)挖填方的累积高度不超过8英尺(约2.4m),明确禁止与特定开发无关的任何高度或累积量的挖填方;7)一个初步地质技术评估应考虑相对的山地稳定性。

这些基本要求中如有任何一项没有被满足,申请人必须在一个市政府所指定的听审员面前说明为何其应该被豁免1项或多项要求。在2004——2014年间,听审员是从城市规划部门的不同等级人员中选出的。自2014年起,听审员改从市法务局挑选。山地信托基金会认为,来自市法务局的代表会对HOD条款进行更为严格的解读。自2004年HOD被立法以来,山地信托基金会已就至少43个山地开发案例表达了意见 。

7 总结和结论

21世纪初的辛辛那提是一座继承了各种山地债务的城市,这些债务并不只是山地本身不稳定性造成的损失。此前几个世纪的资源开发性和破坏性土地使用活动,以及不严谨的工程解决方案(其中不少先于EQ-HS分区),都成为该市及其居民要长期(如果不是永久)负责的历史遗留问题。

近年来辛辛那提在保护其公共基础设施方面变得更加积极主动,但在监督私人地产上的山地开发方面可以也应该做得更多。来自私营部门的山地开发压力是巨大的,而且会在未来变得更大。在非常理想的社区中,仅存的未开发土地往往是山地。许多山地还拥有俯瞰盆地和(或)俄亥俄河的壮观视野,其盈利潜力备受青睐。因为其坡度陡峭,这些山地的开发风险通常更高。

虽然之前的EQ-HS分区是朝正确方向迈出的一步,但它并非万无一失。据传闻,在2003年EQ-HS管控下获批的私人山地开发项目中,至少有一个于2012年发生了大面积坍塌,导致花费了几十万美元的维修费用(图8)。幸运的是,公寓业主可以根据俄亥俄州关于开发商责任的10年时效法规起诉开发商。山地信托基金会在分区审批过程中曾公开评论过这一案件。当灾难发生时,基金会发现其建议中至少有一条未被开发商采纳,就是建筑应该远离山脊线。到目前为止,由当前HOD分区下批准的开发项目尚未发生崩塌问题。

即便如此,该市最好能遵循以下方面来强化其山地开发要求的传递和效力。第一,在房地产界,许多房地产经纪人并不知道HOD区域的分布情况,特别是其与现有或现建住房之间的关系。该市可以通过在其市政网站上提供一张基于地理信息系统的具体地块边界图来解决这个问题,在图上突出标记被HOD覆盖的区域。每当光标移动到计算机屏幕上的HOD地块时,就会弹出一个下拉框解释该HOD的性质和要求。这将有助于使各专业人士和广大公众了解这些地区的山地开发和居住相关风险。

第二,该市还可以实施更严格的HOD分区,要求开发商聘请一名地质技术工程师对该开发项目的所有土地平整和土方工程阶段进行现场监督,确保其按照建议遵循相关工程报告。对于已经得到市政府授权的初步地质技术工程报告,可以进一步要求开发商咨询1位地质学家,该地质学家能够在现场发现和记录任何可能被土木或地质技术工程师忽视的现存滑坡情况。

第三,该市可以补充立法,对任何故意向市政府提交关于建筑许可和变更的错误或虚假信息的HOD申请人(开发商、设计师或房主)进行罚款。山地信托基金会曾目睹了一些此类情况,即申请人以超过其所提交的设计方案规模进行建造,或未能按照承诺采取适当的雨洪控制措施。

最后,该市要填补任何使坡地开发者得以完全绕过HOD流程的漏洞。在2016年,1个申请建造19套住房的人找到了一种合法绕过HOD分区要求的方式,即在城市规划委员会的土地细分法规下直接获得项目批准。最终,政府并未根据HOD流程举行公众听证,使山地信托基金会或其他人能够问询提出疑虑或讨论案件细节。该项目在土地平整和土方工程阶段就出现了问题,住宅在一场暴雨后被洪水冲下了山坡。

总之,辛辛那提建在一个极为美丽却敏感的景观之上,有着一段长时间且代价巨大的滑坡破坏、修复和缓解危害的经历。本文作者强调了与这些山地相关的损失,以及辛辛那提为减少其未来损失和代价而做出的努力。

注释:

图1由科尔曼教皇提供;图2、7、8由埃里克·鲁索提供;图3为1948年Charles Fontayne和William Porter拍摄的《银版摄影术记录的辛辛那提》,由辛辛那提和哈密尔顿公共图书馆提供;图4~6由辛辛那提大学图书馆提供。

(编辑/王一兰)

Cincinnati is a city of hillsides with a history of slope instability. Of the 207 square kilometers that comprise the incorporated area of the city, 39 square kilometers consist of hillsides defined by slopes of 20 percent or greater.

The predominant bedrock strata underlying Cincinnati’s hillsides are the Kope and Fairview Formations. These formations are known to be very reactive to water whereby the shale disintegrates and weakens quickly. It is the Kope Formation that is the most problematic, because the breakdown of its shale results in a material called colluvium. The most common and most destructive landslides in the Cincinnati area are those formed in colluvium.

Cincinnati was settled in 1788 and began to grow rapidly after 1810. By 1850, it was the sixth largest city in the United States. During this growth spurt, many of its hillsides were stripped bare for lumber, and quarried for buildings, foundations,and other related uses. These activities exacerbated natural slope instability problems. As Cincinnati continued growing and expanding into the 20th century, large-scale infrastructure and private development projects increased. When these developments located in zones of colluvium,catastrophic landslides often resulted.

During the late 1960s, public awareness of the problems and complexities of Cincinnati’s hillsides led to concrete action steps that resulted in quantitative and qualitative analyses over the next several years. By 1976, these studies provided a basis for Cincinnati legislating development controls on nearly half of its hillsides.

In 1998, Robert Olshansky published a paper entitled Regulation of Hillside Development in the United States. The paper discusses hillside development from a historical perspective, and it explores how different points of view among design disciplines are likely to approach this type of development in different ways. Notably,his paper concludes with a summary of hillside regulations and ordinances gathered from 190 local governments across the United States, including the City of Cincinnati.

This paper will explore in greater depth,Cincinnati’s hillside regulations from a historical and chronological view point. It will begin with an overview of the study area, illustrating the city’s physical geography and its geology. It will continue with a history of Cincinnati’s settlement and the destructive impacts of human interaction on its hillsides, especially as the city’s population went through initial stages of rapid expansion. Much of this geographical, geological and historical information are referenced from Ph.D. dissertations and thesis research stored in the offices of The Hillside Trust. This historical overview provides context for the following sections of the paper which chronicle the emergence of activism that lead to the establishment of municipal hillside regulations, and to the creation of The Hillside Trust, a non-profit hillside advocacy organization.Much of the information collected in this section is derived from archived newspaper and magazine articles spanning 50 years that are stored with The Hillside Trust. In conclusion, the paper summarizes where Cincinnati has made strides in its hillside regulations, and where it still has room for improving upon them. These conclusions are based on the anecdotal experiences of The Hillside Trust interacting professionally with the city and its hillside zoning regulations since 1976.

1 Study Area

Cincinnati, Ohio is a city in the United States,with a population of 301,301[1]. It is located along the northern banks of the Ohio River in the eastern third of the country. Its central business district (CBD) is built upon an approximately 10.05 square-kilometer, semi-circular plateau elevated safely above the river’s flood plain[2].

This central core (or downtown) is commonly known as the basin (Fig. 1). It is flanked on three sides by steep slopes towering well-over 70 meters above the basin floor (Fig. 2). Secondary valleys,including those belonging to the Mill Creek and the Deer Creek cut through the basin hillsides on the west and east, respectively. Other secondary valleys cut directly into the Ohio River valley. These secondary valleys lead to smaller and shallower troughs on the way up to a plateau, forming a continuous horizon line above the basin.

Of the 207 square kilometers that comprise the incorporated area of Cincinnati, 39 square kilometers consist of hillsides defined by slopes of 20 percent or greater[3]. Generally, these hillsides are wooded with secondary and tertiary forest cover,interspersed with pockets of development, forming a green mosaic during the months of spring and summer.

The region opposite the central core of Cincinnati, along the southern banks of the Ohio River, is comprised principally of the cities Covington and Newport, in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, which is a state directly south of Ohio.These cities are located upon a smaller elevated basin of their own, with hillsides that rise no less dramatically above the basin. This region shares a similar geology and landslide susceptibility to that of Cincinnati and southwestern Ohio. This paper will focus exclusively on the City of Cincinnati.

Cincinnati’s hillside landscape is the result of continental glaciation, which began approximately two million years ago. The last glacial advance began receding just north of Cincinnati around 19,700 years ago[4].

5 哥伦比亚林荫大道工程所导致的1930年滑坡

Landslide in 1930 resulting from development of Columbia Parkway

The predominant bedrock strata underlying Cincinnati’s hillsides are the Kope and Fairview Formations. The Kope Formation is comprised of approximately 80 percent shale and 20 percent limestone. The Fairview Formation is located above the Kope Formation and is comprised of approximately 50 percent shale and the remainder limestone. Around the basin, these formations are located between elevations that are 400 and 850 feet above sea level. University of Cincinnati Geology professor, Paul Potter explains that “all of the shales of these Cincinnati Series are very reactive to water, as they are prone to disintegrating(or slaking) quickly.” It is the Kope Formation that is the most problematic, because it is the principal colluvium-producing bedrock unit[5]. Colluvium is the geologic term for soil, that is composed primarily of clay particles. It develops on top of bedrock, along valley walls, from Kope shale that breaks down from weathering. The most common and most destructive landslides in the Cincinnati area are those formed in colluvium[5].

In addition to colluvium, glacial deposits are scattered throughout the Cincinnati region,including unstable lake clays. These clays are remnant deposits from lakes that formed from glacial melt water. Lake clays are problematic in that they are also highly susceptible to landslides[6].Unlike other parts of the United States, such as California, where landslides are often swift,dramatic, and can result in sudden loss of life,Cincinnati’s landslides are usually slower moving.Often, they creep at a rate of a few centimeters per year but are no less significant when it comes to structural damages and economic losses over time.

Following American’s war for independence from Britain (1775——1783), the newly-formed United States was determined to settle lands west of the Allegheny Mountains[2]. These lands, including what are now known as southwestern Ohio and northern Kentucky, possessed an abundance of resources, including virgin timber, fertile soil, fresh water, and a rich population of game animals.

2 Impacts of Early Land Use and Settlement

People of European descent settled the land which is now Cincinnati in 1788. After establishing three different camps along the Ohio River, they eventually settled on the higher elevation and relatively expansive opening offered by the basin area[2]. The population was slow to expand due to ongoing skirmishes with indigenous tribes such as the Miami, Shawnee, Wyandot and Delaware, who fiercely defended their homelands[2].

Following the U.S. government’s decisive victories against the Native Americans in 1794 and again in 1811, the population of Cincinnati began to grow rapidly[2]. With its location along a major inland river, Cincinnati was both a gateway to the western frontiers of the United States, as well as a destination for those seeking new beginnings in a new land. U.S. Census figures show that Cincinnati’s population at least doubled every ten years between 1810 and 1850. By 1850, it was the sixth largest city in the United States with a population of 115,435[2].

The rapid increase in population exerted an increased demand for natural resources, particularly lumber. In 1815, Daniel Drake, a prominent doctor and a naturalist wrote that wood was the “chief article of fuel and that it was obtained from the“surrounding hills.”[7]In addition, the hillsides were used for agriculture, plowed for crops, and terraced for vineyards[8]. Livestock grazing on the “sloping hills of Cincinnati was common in the 1800s”[9]and may have been a factor in the destruction of vegetation, the formation of terraces, and accelerated erosion. A rare mid-nineteenth century panoramic series of daguerreotype photographs by Fontayne and Porter preserved in the main branch of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton,portrays the Cincinnati hillsides modified and stripped of vegetation (Fig. 3).

Quarrying was another industry by which the hillsides were significantly impacted.Limestone was a preferred construction material for buildings, foundations and retaining walls[10],and to a lesser extent for lime mortar, roadbeds,and pavements[11-12]. Besides river quarry beds,hill quarry beds were another primary source of Cincinnati limestone[11-12]. The most desirable section of the hill quarry beds was the upper 50 feet (about 15m) of the Fairview Formation[13].This formation underlies the uppermost portion of the hillside valley walls. In 1826, Drake described the area near the summit of Cincinnati’s hillsides as “naked perpendicular cliffs,” where the upper Fairview limestone stood in vertical relief from quarrying activity (Fig. 4). Early land use, including deforestation and quarrying activity initiated largescale landslides in Cincinnati[14-15].

During the last third of the 1800s, the advent of inclined railroads (inclines), trolleys and railroad lines made it possible for large numbers of people to “escape the dirty, crowded basin” and live some distance from their work[2]. Beginning in the 1870’s,a total of five inclines would be built on various hillsides rimming the downtown basin (see example Fig.4). These inclines traversed the steep slopes with passengers, building materials, and commercial goods on a scale by which horse-drawn carriages were incapable of matching. New neighborhoods developed around and beyond the hillsides in communities such as Mt. Adams, Mt. Auburn,Clifton and Price Hill.

These inclines revolutionized the city’s growth by providing Cincinnati with cheap and convenient access between the basin and the hillsides for the first time in its history[2]. It also led to the city’s greatest expansion in land area. Between 1869 and 1918, Cincinnati reached out and annexed more than 168 square kilometers of land, and the population of the entire city approached one half million people[2]. The construction and ongoing operation of the inclines also resulted in landslides.

In the late 1920s, construction began on a modern roadway for automobiles that would become known as Columbia Parkway. A forerunner of America’s interstate highway system, Columbia Parkway’s purpose was to create a major caroriented transportation corridor to connect downtown with the eastern suburbs. It required significant engineering and earthworks along the mid-slope of a steep and sprawling hillside system that runs parallel to the Ohio River. The geological impacts of this roadway are still being felt well into this century, as discussed below.

3 Impacts of Human Interactions on the Hillsides

There were mass slope movements in the Greater Cincinnati region, long before humans arrived[16]. However, it is the intensive land use of Cincinnati’s hillsides following its settlement in 1788, that exacerbated slope instability. There is historical evidence that widespread deforestation,farming, quarrying, and livestock grazing all negatively impacted the natural slope and drainage patterns of the region’s hillsides. Landslides have been a problem in Cincinnati since the early to mid-1800’s, with deep landsliding (greater than five feet in depth) probably going unrecognized[14-15].

Large-scale infrastructure and private development projects increased as the city grew and matured. Many of these involved hillside areas. When these developments located in zones of weak substrate (colluvium), the results were often catastrophic. The following summary highlights some of these disasters[14-15].

·In 1926, an extensive base-failure landslide occurred west of the downtown basin from removal of the toe of the slope[17]. A massive cut measuring 600 meters wide by 12 meters high was made into the bottom of a slope. The hillside moved, extending more than 450 meters upslope. Ground disturbance extended below the terraced cut face, as the ground bulged up some four and a half meters. The total surface area of this landslide was over 350,000 square meters.

6 1972年克利夫顿高地滑坡,描绘了滑坡的巨大体积

Clifton Heights landslide in 1972, depicting the shear volume of hillside that failed

·In 1930, a large landslide occurred during construction of Columbia Parkway. This was the result of widening narrow Columbia Road,by cutting the hillside above the roadway and dumping cut material below it. Columbia Parkway has experienced continued landslides since its completion. It is a major arterial roadway, carrying thousands of vehicles per day. Annually, the oversteepened slopes above the Parkway breach the retaining walls that attempt to hold it back. These landslides are significant enough at times to close some (or all) of the eastbound and westbound traffic lanes for several hours at a time (Fig. 5).

·In 1972, a large landslide resulting from the construction of an apartment building and adjoining parking lot several years earlier, created a head scarp 55 meters long and nine meters high in Clifton Heights immediately north of the basin(Fig. 6). About 12 apartment units were temporarily vacated, as were a gas station and manufacturing facility downhill from the slide[18]. The right and left flank of the landslide are still visible today from one of downtown’s tallest buildings, the Carew Tower.

·In 1973, the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) made a two meter vertical cut into the toe of the Mt. Adams hillside, to build entrance and exit ramps for the new Interstate 471 bridge spanning the Ohio River. When gas and water lines began rupturing, the city ordered the permanent evacuation of 15 families in this hillside neighborhood[19]. Seven years later, government officials approved a solution which was to build a concrete wall 390 meters long and 30 meters deep,using a system of drilled piers and cables to retain the massive hillside. During construction of this wall, concussions from pile driving triggered another slope failure, leading to the permanent evacuation of approximately 30 more families[19]. When the wall was finally completed eight years later in 1981, it was at a cost of $22.2 million[20]. At the time, this was one of the costliest landslides in the history of the United States.

The annual costs from landslide damage to public infrastructure alone can be staggering. A study of landslide repairs compiled by students and faculty of the University of Cincinnati, found that the annual direct cost of emergency repairs to local streets in the City of Cincinnati is about $500,000 annually[5]. Deferred repairs of landslide damage to Cincinnati streets amounted to approximately$18.5 million in 1987[21]. These findings were part of a larger special commission established in 1985 to investigate and proactively address the care and maintenance of Cincinnati’s infrastructure,discussed more fully below. It is important to note that these figures do not include the costs of landslide damage to private property within the city, the figures of which are much more difficult to quantify and obtain. Slope instability and damages to residential construction on Cincinnati’s hillsides are widespread problems.

4 Activism, Action and Founding of The Hillside Trust

May 4, 1967 is a benchmark in Cincinnati’s history for establishing hillside protection measures.On that date, a “Hillside Forum” was convened at the Cincinnati Art Museum in Mt. Adams.Presumably, this site was chosen because of its picturesque hilltop location, and its commanding view of the downtown basin.

A flyer advertising the Forum, urged interested citizens to attend to “discuss the FUTURE of Cincinnati’s hillsides.” The Forum’s speakers included City of Cincinnati Department directors, and other professionals representing housing, development, the arts, and the environment. This daylong event produced various action steps, including plans to conduct quantitative and qualitative analyses of the city’s hillsides.

In 1969, the Cincinnati Planning Commission published a “Hillside Study.” It identified 23 hillsides within the city possessing such qualities as natural community dividers, backdrops of vegetated greenery, and focal points for housing areas[22]. Three years later, the Cincinnati Planning Commission hired Richard A. Gardiner &Associates to produce “The Cincinnati Hillsides:Recommended Design Process and Action Program.” The main theme of this report included a step-by-step process to be followed in the next several years to insure proper hillside development[22]. A noteworthy recommendation in the report included the establishment of a nonprofit organization that would buy up undeveloped hillside land and impose design controls when the land was sold for redevelopment[23].

During the late 1960s to 1970s, Pope Coleman was known in city and community circles as an advocate for the arts, the environment, and urban issues. He was one of nine speakers at the 1967 Hillside Forum. He also served as chairman of the Cincinnati Planning Commission’s Hillside Advisory Committee, and in 1971 he established the non-profit Cincinnati Institute, whose mission was to enhance urban quality-of-life issues.

Under Coleman’s leadership, the Cincinnati Institute worked closely with the Cincinnati Planning Commission on hillside research and preservation efforts. In 1973, the National Endowment for the Arts awarded the Cincinnati Institute a $40,000 grant, under its “City Edges”Program, to help preserve and enhance the city’s hillsides. Cincinnati was one of only 37 applicants out of 367 to receive this funding[3]. A portion of this grant went towards analytical research to define the characteristics of Cincinnati’s hillsides, and to create design guidelines.

The Institute hired legal counsel to establish interim control measures and to draft language for eventual zoning ordinances dealing with this issue. Grant funding was used to interview 100 Cincinnatians to record their impressions of the city’s hillsides. The transcripts of these interviews provided invaluable insights into the positive impact that hillsides have upon the psychological wellbeing of the city’s residents[24]. The remainder of the grant served as seed money to establish a non-profit hillside organization, as recommended in the 1971 study by Gardiner & Associates. This non-profit was founded in October, 1976 as “The Hillside Trust.”

The Cincinnati Institute organized and summarized the multitude of hillside research conducted in 1973 and 1974. In 1975, it contracted with San Francisco planner, Rai Y. Okamoto to perform final field surveys, photographic documentation, and additional hillside analysis.This work culminated in a seminal report,“Cincinnati Hillsides: Development Guidelines”prepared for the Cincinnati City Planning Commission in late 1975. The document provided detailed research into geology, soil characteristics,vegetation, tree patterns, public and private uses,visual characteristics and other urban planning considerations. By the late 1970s, the Cincinnati Institute ceased operations as The Hillside Trust began to grow.

5 Hillside Protection Measures Established

In June, 1976, the Cincinnati Planning Commission formally adopted a document known as “Cincinnati Hillsides: Development Guidelines.”At the time, the Planning Commission was finalizing special regulations called Environmental Quality Districts (EQD). EQD was an overlay zoning designed to “assist the development of land and structures in order to be compatible with the environment, and to protect the quality of the urban environment in those locations where the characteristics of the environment are of significant public value and are vulnerable to damage by development permitted under conventional zoning and building regulations”[25]. EQD classified four categories: public investment areas, urban design,community revitalization, and hillsides.

It is the hillside component of these special zoning overlay districts, however, that was the driving force behind drafting EQD in the first place.The city recognized the landslide-prone nature of its hillsides and understood that hillside regulations were needed to prevent unregulated development from exacerbating this problem. All 23 hillsides identified in the 1969 “Hillside Study” were designated as Environmental Quality-Hillside Districts (EQ-HS).The “Hillside Study” had considered these hillsides critically important based on having at least 50 percent of their area within one or more of the 23 designated hillsides, and containing at least four of the following six elements: 1) Slopes of 20 percent or greater; 2) Existence of Kope formation;3) Prominent hillsides viewable from a public thoroughfare located in a valley below a hillside identified within the Cincinnati Hillside System;4) Hillsides that possess views of a major stream or valley; 5) Hillsides that function as community separators or community boundaries as identified in a community plan accepted and approved by the City Planning Commission; and 6) Hillsides which support a substantial wooded cover.

Despite years of effort, less than half of the 23 hillsides designated under the EQ-HS were legislated under city zoning. Individual community councils had the responsibility of recommending to City Council the adoption of established EQ-HS districts within their own neighborhoods. Perhaps a lack of urgency led to the failure to adopt EQHS districts in these neighborhoods. Nevertheless,all basin hillside communities including East Price Hill, Mt. Auburn, Clifton and Mt. Adams adopted and legislated EQ-HS zoning, beginning as early as 1976. Not only do these hillside communities possess commanding views of the downtown basin, they also provide striking natural landmarks when viewed from the basin floor (Fig.7). Ironically,at the same time the City began enacting measures to proactively manage its hillsides, landslide losses in the Cincinnati area during the 1970s, were the highest per capita ever documented for a U.S. urban area[26].

In the mid-1980s, a blue-ribbon group of Cincinnati business and academic leaders was formed to recommend ways to improve and protect the city’s assets, including measures needed to finance the suggested improvements. In 1987,this committee produced what is known as the Smale Infrastructure Commission Report, headed by John Smale, then chairman and chief executive officer of the Proctor & Gamble Company. More than 100 recommendations were listed in the report, four of which pertained to hillsides. The most important of these hillside recommendations were adopted by Cincinnati in 1989.

The first recommendation involved funding an initial inventory of all the city’s retaining walls,including future budget allocations to keep the inventory current. As of 2018, nearly 80 linear kilometers of retaining walls were documented within the city[27]. The success of this original effort has grown into the Retaining Wall and Landslide Stabilization Program, which has the goal of“bringing all existing walls into good condition,and stabilizing landslides that impact the City’s roadways”[27].

Each City wall is inspected on a six-year cycle, which assists in determining whether a wall needs to be replaced or rehabilitated, if necessary.Funding for this program is carefully allocated each year with a focus on addressing the most urgent needs first, to prevent serious damage to city streets and utilities. Of note, this program has not curtailed landslides either above or below the City’s retaining walls. It has simply slowed and lessened immediate impacts closest to city streets and utilities.

7 从盆地向北仰望克利夫顿山坡的主要街道

Main Street from the basin floor looking north towards the Clifton hillside

The second recommendation implemented was the establishment of a Geo-Technical Office within the City’s Department of Transportation and Engineering. Since 1989, the City has maintained a full-time engineering geologist (a geologist trained with an engineering background),and a full-time geo-technical engineer. Together,the primary duties of these positions are to provide geo-technical expertise concerning landslide stabilization and prevention within the public rightof-way, and on any other property controlled by the city. The geo-technical staff also consult with all other city departments, including the Departments of City Planning and Buildings and Inspections.Specifically, they assist building plan examiners in their review of projects in landslide-sensitive areas.The Smale Report originally recommended that a geologist be one of the two professionals employed within the Geo-Technical Office. A geologist is more inclined to recognize pre-existing landslide conditions, and to reference the historical record of local landsliding, which otherwise is more easily ignored or forgotten. For its part, The Hillside Trust serves as a valuable check on this issue and provides an institutional record of memory for historical landslides, hillside use, and advocacy.

6 The Hillside Trust Establishes its Hillside Advocacy Role

8 2012年普赖斯山某区域的修复工作,该区域在邻近盆地西边公寓的位置发生严重塌方

Remediation work on a hillside in 2012 that collapsed perilously close to condominiums west of the basin in Price Hill

When The Hillside Trust was formed in 1976,it became clear early on that it lacked the financial resources to implement one of its charter purposes,which was to be a land bank that purchased and held hillside land, then supervised its future development in a responsible manner. Instead, The Hillside Trust emphasized its other charter purposes of: 1) research and education; 2) land conservation; and 3) advocacy of responsible land use.

Following the 1987 Smale Infrastructure Commission Report, and a 1988 Conference hosted by The Hillside Trust entitled, “Dollars and Sense: The Economic Impact of Landslides in Cincinnati and Hamilton County”, The Hillside Trust embarked upon an ambitious research effort in 1989. Completed in 1991, this research was published as “A Hillside Protection Strategy for Greater Cincinnati.” Volume 2 of the research included detailed hillside analyses and a series of maps pertaining to visual quality,landslide susceptibility, environmental-ecological quality, development susceptibility, visual and environmental sensitivities, and hillsides prioritized for protection. Volume 3 of the research included 145 hillside-specific development guidelines,drawing from the information and analyses produced in Volume 2. Volume 1 consisted of a short introduction to the study.

More than 300 copies of this research were sold (at cost) to various municipal planning departments and private planning and design firms across the United States and Canada. The Hillside Trust hosted a workshop in 1992 and directed communications to local governments within the metropolitan region, recommending that they adopt the hillside development guidelines.Ultimately, neither the City of Cincinnati nor any other local jurisdiction adopted the guidelines.However, in 1997, Cincinnati recognized The Hillside Trust’s growing professional reputation within the region as an expert on hillside and landslide issues. The city began notifying the organization about hillside developments proposed within its EQ-HS districts and invited it to publicly comment on them. Between 1997 and 2003, The Hillside Trust provided either written or oral testimony on at least 28 development proposals within these districts. While The Hillside Trust is not opposed to development, it will cooperate with local residents, when necessary, to expose plans that it believes will have a negative impact on the surrounding environment, or to highlight any plans that lack engineering foresight. The Hillside Trust can undertake this role because of the expertise of its trustees, technical advisors, and its executive director.

In early 2004, Cincinnati unveiled a new zoning code. All EQ-HS zoning was replaced with a new classification called Hillside Overlay Districts(HOD). Whereas less than half of the former EQHS districts were codified into law, the new Hillside Overlay Districts provide city-wide application.Property is zoned under an HOD classification if any portion of it contains a slope of 20 percent or greater, and/or any part of it is designated as moderately high or high in landslide susceptibility,according to a 1980 “Landslide Susceptibility Map produced by Sowers and Dalrymple for the city. Both the 1969 “Hillside Study” and the 1975“Cincinnati Hillsides Development Guidelines”report were incorporated in the Hillside Overlay District zoning as supporting documentation.

Hillside Overlay District zoning includes a set of base development requirements, under which any application seeking a building permit is obligated to meet. Section 1433-19 of the Cincinnati Zoning Code lists these requirements:1) Any new building or building alteration must be contained within the maximum building envelope(the parameters of which are defined by the City);2) Buildings proposed on top of the hillside must be taller than wider to accentuate the vertical dimension; 3) Buildings proposed below or above the brow of the hill must be staggered or stepped in depth and width to match the topography;4) Rooftop utilities and mechanical equipment are either to be avoided altogether, or screened and sound controlled; 5) All pervious surfaces remaining after completion of construction must be landscaped in trees, shrubs, grass, or other ground covers to promote hillside stability and reduce excessive water runoff; 6) Excavation and fills should not exceed eight feet in cumulative height. Excavation and/or fill of any height or cumulative amount that is not tied to a specific development is expressly prohibited; 7) A preliminary geo-technical evaluation should address relative hillside stability.

If any one of these base requirements is not met, the applicant is required to appear before a city-appointed hearing examiner to testify as to why a variance should be granted to exempt one or more of the requirements. Between 2004 and 2014,the hearing examiner was selected from the ranks of the city’s Planning Department. Since 2014, the hearing examiner has been selected from the city’s Law Department. It is The Hillside Trust’s opinion that representation from the city’s Law Department has resulted in stricter interpretation of the HOD language. Since the HOD was legislated in 2004,The Hillside Trust has publicly commented on at least 43 hillside development cases.

7 Summary and Conclusions

Cincinnati of the early 21st century is a city that has inherited various hillside liabilities extending beyond the natural instability of its slopes. Exploitive and detrimental land-use practices from previous centuries, and negligent engineering solutions, many of which pre-date the original EQ-HS zoning, have created a legacy of long-term (if not perpetual) responsibilities for the city and its residents.

Cincinnati has evolved to a point of being more proactive in the protection of its public infrastructure in recent years, but more could and should be done to strengthen oversight of hillside development on private property. Pressures from the private sector to build on hillsides are strong and will only grow stronger in the generations to come. In highly desirable neighborhoods, often the only undeveloped lands remaining are those occupied by slopes. Many hillsides also possess spectacular views of the basin and/or the Ohio River, and are highly prized for their profit-making potential. These hillsides often carry an even higher development risk, because of significantly steeper grades.

While the former EQ-HS zoning was a step in the right direction, it was not foolproof. Anecdotally, at least one private hillside development approved under the former EQ-HS in 2003, failed in 2012 when a massive section of hillside collapsed, resulting in a repair bill in the hundreds of thousands of dollars (see Figure 8).Fortunately, condominium owners were able to sue the developer under the State of Ohio’s 10-year statute of limitations pertaining to developer liability. The Hillside Trust had publicly commented on this case during the zoning approval process.When the failure occurred, it discovered at least one of its recommendations, siting the building further away from the brow of the hill, was not followed by the developer. To date, no known slope failures have occurred involving development projects approved under the current HOD zoning.

That said, the city would be wise to strengthen the delivery and effectiveness of its hillside development requirements with the following improvements. One, within the real estate community, many real estate agents are unaware of Cincinnati’s Hillside Overlay Districts, especially as they relate to existing housing or new construction.The city could remedy this problem by providing a Geographic Information Systems (GIS) parcelspecific boundary map on its municipal website,highlighting the areas covered by HOD zoning.Whenever a cursor goes over an HOD parcel on the computer screen, a drop-down box could appear explaining the nature and expectations of the HOD. This would serve to notify various professionals and the public at-large about the risks associated with hillside development and hillside living in these areas.

Two, the city also could implement stronger enforcement of its HOD zoning by requiring developers to pay for a geo-technical engineer to be on-site during all grading and earthworks stages of the development, ensuring that the engineering report is being followed as advised. The preliminary geo-technical engineering report already mandated by the City, could be strengthened by requiring developers to engage the services of a geologist,who is trained to observe and document any preexisting landslide conditions on site that might otherwise go unnoticed by civil or geo-technical engineers.

Three, the city could add legislation fining any HOD applicant (developer, designer or homeowner) who knowingly submits false or misleading information to the city concerning building permits and variances. The Hillside Trust has witnessed several situations where an applicant either built the project larger than submitted in the design plans or failed to implement appropriate storm water control measures as promised.

Finally, the city could close any loopholes that allow hillside developers to navigate around the HOD process altogether. In 2016, an applicant for a 19-home development found a way to legally maneuver around HOD zoning requirements by gaining project approval directly from the City Planning Commission under its subdivision regulations. Ultimately, there was no public hearing under the HOD, in which The Hillside Trust or others could ask questions, raise concerns, or discuss details of the case. Problems arose during the grading and earthworks phase of the project when residential properties were flooded downhill following a torrential rainstorm.

In closing, Cincinnati is built upon a spectacularly beautiful yet sensitive landscape, with a long and expensive history of landslide damages,repairs and mitigation. This paper highlights the liability side of interacting with these hillsides, and what Cincinnati has done to begin minimizing its exposure to further damages and costs.

Notes:

Fig.1 courtesy of Pope Coleman, Fig.2,7-8 courtesy of Eric Russo, Fig.3 © Charles Fontayne and William Porter’s Daguerreotype View of Cincinnati, The Cincinnati Panorama of 1848 in the Collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County, Fig.4-6 courtesy of University of Cincinnati Library.