城市设计在基督城重建中的作用

2018-03-11丹尼尔布兰德雨果尼科尔森

丹尼尔·布兰德 雨果·尼科尔森

施腾鑫 [译]

1 城市设计与抗逆力的定义

“城市设计”一词出现于20世纪中叶,1956年,由哈佛大学设计研究生院主办的现代会议中提出[1]。美国城市规划者和理论家Edmond Bacon通过将城市作为“意志行为”和“重大事故”[2]加以区分而对城市设计的理念进行定义。时至今日,此定义依然以中立的态度对该学科的内涵作出优雅的概括。城市设计实践的改变在20世纪后半叶和21世纪初得到广泛传播。随着时间的变化,城市设计与不同的因素相互结合,如工业化和后工业化的城区和城郊情况,经济、文化、全球化对空间设计的影响,城市化带来的区域分布和竞争不均衡,可持续发展、气候变化以及自然灾难对当代城市社区的影响。最终,城市设计成功地与许多专业相结合,包括设计、建筑、科学、经济和社会服务。跨学科结合的目标在于建立新的社区,与可持续性的地面景观产生经济和社会联系。

“抗逆力”是城市设计中的一个环节。抗逆力在不同学科中的含义都不相同,但所有定义都大致关于系统、整体、社区或个人的能力能够承受强烈冲击并维持其基本的功能[3]。抗逆力也指灾后快速有效恢复的能力以及承受更大压力的能力[4-5]。

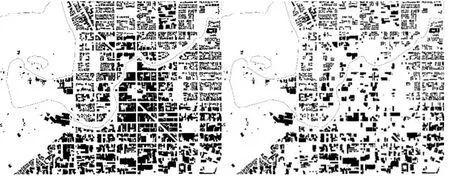

图1 / Figure 1基督城中央区域震前和震后对比图Figure grounds of central Christchurch pre- and postearthquake来源 / Source: William Thornton

21世纪灾难文献首先关注的是气候变化带来的负面影响。人们将近年来发生的灾难文献进行分类,如飓风(卡特里娜和桑迪)、海啸(印度洋和日本海)、地震(智利和海地),并对后续的社区规划方案进行讨论。这些方案对如何降低灾难影响并提高适应力提出调查信息。文献内容囊括了城市环境的不同规模,并采用空间规划理论学家[6]提出的城市填充、城市拓展和新社区对比性方案作为备选性适应策略,以及采用了城市规划和设计者Vale[7]对近年重建城市的社会经济成果和基础设施成果提出的疑问。曼哈顿的Bergdoll[8]和新奥尔良佛吉尼亚建筑学校的Roettger[9]针对潮汐淹浸提出了设计方案、适应性建筑方法和社区构建策略。Aquilino[10]对洪水、地震、海啸和火灾等灾难发生后的重建提出质询,其关注点集中在建筑设计、建筑过程和材料选择。

Godschalk[11]对城市理论和抗逆力理论的交集点进行了研究,他也对自然灾害相关的城市抗逆力提出探讨。Jianguo Wu和Tong Wu[12]在抗逆力范畴内提出了经典城市设计理论,并围绕动静辩证法针对未来可持续性设计实践中的热点领域提出设想。

一些学者对特定问题进行了研究。这些研究与坎特伯雷市地震后的城市、地面景观和建筑设计有关。Bennett等人[13]对基督城地震后的重建过程进行了论述和探讨。Swaffield[14]对基督城重建中涉及的场地类型和文化进行了探讨,从而找出负责指导的中央政府管理过程和社区自营项目之间的关系。Wesener[15]则更加具体地描述了基督城过渡性社区开创的开放式空间。Jacques等人[16]评估了基督城医院系统的运行成效,并提出一种方法,从地震准备策略的角度对未来的医院运行情况进行预测。然而,对于城市设计能够制定出城市抗逆力规划方案的潜在益处,文中并未提及。本文旨在对新西兰基督城的案例研究进行讨论来解决此问题。

本文将讨论城市设计、抗逆原则和过程如何对基督城在2010年和2011年的地震灾难后产生的重塑作用(图1),并重点探讨3个议题:城市设计让灾后重建城市成为低楼层绿色城市、城市设计让公共社区更具抗逆力、城市设计给各个城区带来更好的项目投资,最后探讨城市设计尚未解决的问题。每个议题将针对基督城近7年来的重建实际案例进行讨论。

2 城市设计让灾后重建城市成为低楼层绿色城市

通过公众咨询流程产生愿景:共享理念

作为开发市政府制定的《中央城市规划草案》(DCCP)[17]的一部分,政府从震后的二月份开始,面向基督城市民举行为期3个月的公众意见征集活动(共享理念),用于起草中央城区的重建方案。“共享理念”活动的网站共获得58,000个点击量并在4个关键领域征集公众意见:移动(运输)、市场(商业)、空间(公共空间和娱乐)和生活(综合用途)。活动采用传统方式和社交媒体网络方式同时进行。活动中举行了一项超过1万名来访者的互动展出、1个国际专题讲座、10个社区研讨会、超过100个利益相关者会议,并在5个不同的场地举办一项48小时的设计挑战赛。超过6周的公众参与共产生了106,000个创意,促成了《中央城市规划草案》的诞生[18]。“共享理念”活动为塑造城市共同的景观奠定了基础,并为城市重建项目带来了广泛的公众认同。这种类型的公众咨询和社区参与方式成为创建方案的极佳流程,公众可以通过不断参与来进行持续讨论。公众咨询产生的两大主要结果达成了构建低楼层以及绿色城市的共识。

低楼层城市

由于高楼引起的视觉障碍以及当前存在的城市研究和补救措施,令公众对震后再次构建高楼层城市极为反感。《中央城市规划草案》大胆提出首创理念,将楼层高度限制在28m或7层以内(与华盛顿纪念碑的高度相同),路墙限高21m(图2)。这种组合方式使横截面之比为1:1,令街道的视觉感受很好。同时,这也能让冬日的阳光照射在道路的一侧。

经济影响研究结果表明,以基督城中央城区的岩土工程条件,若建造超过6~8层的建筑将需要构建昂贵的结构系统,因此建筑的层数最好保持在6~8层。《中央城市规划草案》采纳了28m限高的提议并获得市议会一致通过。办公需求研究表明,基督城中央城区的拟建办公楼层空间,在中央商务区或办公楼区内应均匀分布并符合28m限高的规定。《基督城中央城市重建方案》确定了28m限高的规定,这令重建的中央商务区更为宽阔,缔造出一个充满活力、繁荣的综合性中央城市。

图2 / Figure 2中央城市蓝图中低楼层城市模拟图A redeveloped Otakaro Avon River from the Draft Central City Plan来源 / Source: 基督城市议会 / Christchurch City Council

绿色城市

新的重建方案中存在许多方法,可以让基督城成为更显绿色的城市。《中央城市规划草案》和《基督城中央城市重建方案》[19]都规定,必须环绕Ōtākaro Avon河和教堂广场拓展绿色开放式空间的布局网。根据城市既定的停车场空间规划,城市的布局焕然一新。对Ōtākaro Avon河的重新塑造,使之成为主要的室内公共生活空间(图3)。在和首位土著Ngai Tahu的亲密合作下,重新开发方案中包含河流步道、一些重要的艺术景致和大量的本地沿岸居民。

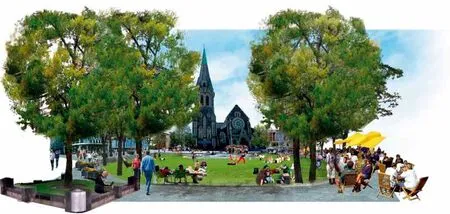

传统的教堂广场是含有道路的空间,原先就包含多条马路,是有轨电车和巴士的主要出发点。在20世纪90年代后期,这里经过大规模的整修,在环绕广场的周边区域修建了一些慢速机动车通道后,这里便不再受到公众青睐。“共享理念”活动中收到的反馈信息强烈要求在中央城区建设更加亮丽的绿色空间。Ōtākaro Avon河的重新开发工程已大部分完工,但教堂广场的绿色改造工程仍在规划阶段(图4)。

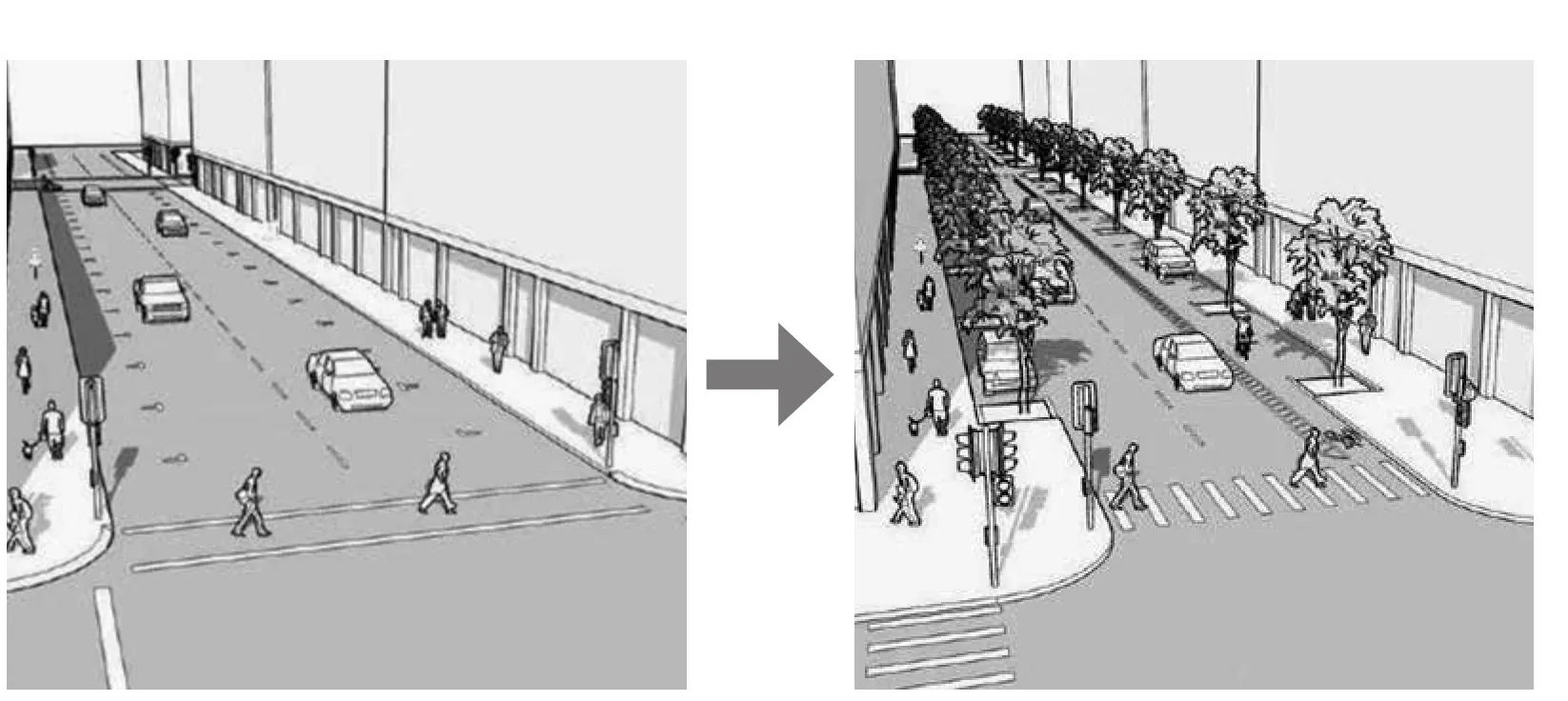

关于“无障碍城市”的内容作为新增章节,后来添加到CCRP内,并提出了许多措施,用于提高中央城市街道的品质,其中包括将市内车速降至30km/h并改善行人和骑行设备等。作为工程的一部分,人们重点关注的是,将街道上超过500个停车位用更加宽阔的人行道、道旁树和雨水花园代替。基督城中央街道和空间设计指南中写明,完工的街道环境将拥有更为绿色且更加可持续的中央城市空间(图5)[19]。

紧凑型城市

对于拓宽城市设计的目标,DCCP和《基督城中央城市重建方案》(CCRP)[20]要求重新建造一个更加紧凑的低楼层商务核心区,增加室内居民的人数和密度,并在核心区域周边推动综合性开发(图6)。核心工程周边区域的重新开发由政府牵头,旨在吸引投资并重新建设中央商务区。这些工程包含一个地铁枢纽、一个会议中心、一个中央图书馆和一个新的巴士站。

DCCP采纳了融合方案来进行重建,其中包含大量的工程项目和实施工具,其目的在于保持激励机制和规章制度之间的平衡,完成主要的刺激项目和公共空间项目,同时兼顾可持续性、住宅、艺术和运输项目。CCRP更关注的是,在大量刺激项目中包含规划愿景,并且当项目涉及对关键公共设施和经济基础设施的重建(如医院和会议中心)时,应更谨慎地执行政府优先事项。

东部框架

DCCP提出采用建筑形式规划法规来进一步推进紧凑型商务核心区建设,而CCRP则主张用干预手段来建立“绿色框架”,重现19世纪环绕城市中心的公园区(最早于1850年在Jollie计划中提出)[21],并在环绕核心区域强制性地征用大面积土地。东部框架用于进行中等密度的综合住宅区开发,同时南北线形公园大约分布在中心区域约30m宽的范围内。由于土地成本的持续上涨,南部框架的土地不会执行强征;但根据建筑形式规划法规,公共通道框架和中央城市学校已获准建立,用以限制开发潜力。设定东部框架的目的是在这里建造可以容纳超过900个公寓的综合住宅区。此项工程的谈判将与一个独立开发商单独进行,确保开发工程的统一性,从而获得激励机制对城市建设的长期获益。“设计框架”与一系列的城市设计控制手段,同属于协议内容的组成部分。这代表建设将采用合作方式进行,在Fletchers、中央政府和当地议会之间重建城市。建筑的布局由开发商提供,街道环境和公共空间由王室和基督城市议会共同确定。

都市游乐场

在东部框架的北部边缘地带,王室和市议会对重要公共空间的开发提供资助。本地居民称此地为都市游乐城或Margaret Mahy家庭游乐场,以此命名来纪念新西兰著名儿童作家(图7)。此地已经成为重建项目的重点区域,无论昼夜均吸引数千名儿童及其家庭前来游玩。这里也是青少年安全的玩乐场所。

东部郊区重建

由于政府决定在此处对原先脆弱的住宅区进行重建,这令Avon River沿岸(图8)低地和港口山区的陡峭空地上腾出大片土地以供建设。土地上只有草丛和林木,表明这里属上市公司Regenerate Christchurch的管理范围。对这片土地的规划和公众参与活动尚在进行。土地由王室和市议会共同所有,目前仍存在一些问题尚待解决,其中包括“红色地带”的所有权归属、土地用途和管理方式。

由于遭受地震袭击,重建后的基督城将变成一座更为绿色的城市。CCRP规定,围绕中央商务区的公园带和Avon 河的必要重建工程,将在沿岸建造一道环保的洪水缓冲区。在东部郊区已被划为红色地带的土地上,有许多潜在的交通要道可供食品生产或娱乐。在临近市中心的区域以及中央商务区和海岸线之间的郊区,公众拥有的绿色空间数量正在显著增加。这些可能性通过大量的社区咨询和严格的规划策略获得,从而让基督城的地面景观和住宅区获得重建,并能够将基督城在未来变成一座紧凑、可持续和宜居的城市。

图3 / Figure 3中央城市蓝图中重新开发的 Ōtākaro Avon 河A redeveloped Ōtākaro Avon River from the Draft Central City Plan来源 / Source: 基督城市议会 / Christchurch City Council

3 城市设计让公共社区更具抗逆力

街道网络、交通要道和开放空间

自2010年和2011年地震后,基督城的规划网络和恢宏的市内开放空间为民众提供了有效并具有抗逆性的建筑格局。这一点从其他城市的角度得到了证实[22-23]。交错的历史街区具有的灵活性和备选方案,无论从应急角度或是在建筑拆除和重建期间,都能让街道的封闭性降至最低。市内公园可以为震后地区的民众提供即时的庇护,并可以作为研究基地用于国际研究和营救行动[24]。

地震发生前,基督城市内最有活力并最具吸引力的中央城区的市区建筑之一是交通要道。这些交通要道原先用作服务通道,特别是用于市中心南部的工业建筑。随着工业的衰败,许多仓库转而用作零售商店、酒店和住宅,使所属区域变得繁荣。这些区域的建筑中,许多已在地震中损毁或无法获得保险理赔(如 Lich field 大道和 Sol 广场)。DCCP 和CCRP 均已要求对这些网络形态交错连接的市内建筑进行二次修复。在零售区,在获得资源许可证书之前,必须保证针对至少一半街区(或7,500m3)的开发计划大纲(ODP)起草完毕。ODP的其中一项要求是修建南北大道。随着ODP的内容大部分已拟定完毕,已经有不少大道和庭院(图9)在零售区建造完毕 — 这并不是用作服务通道,而是用于鼓励公众经过这些通道进入零售和酒店所在区域。类似地,南部框架和一些大型的重要项目,包括司法和紧急服务区、创新区和会议中心在内,都已纳入公共大道和庭院的设计之中。这座城市见证了人工设计的休闲风格给传统市区带来的转变,让震前基督城内建筑变成重建后的城市名片。

图4 / Figure 4中央城市蓝图中设想的绿化程度更高的教堂广场Greener Cathedral Square from the Draft Central City Plan来源 / Source: 基督城市议会 / Christchurch City Council

重塑传统城市可以给当代商务类建筑的设计(带有大型开放式楼面)带来一定优势,这一点与其本身定位并不矛盾。后者给城市塑造带来了新的创意,可以将传统意义上的公共空间变为私人空间,这是因为市内一些区域的新通道和庭院是私人使用的(如这些通道并非按公共街道进行设计)。这就是对遭受自然灾害而获得重建的现代城市房地产开发的真实情况,其公共投资的空间很小。基督城重建的核心问题在于,商务建筑和住宅的分类不断地快速更新,其使用情况和规模发生了根本性的变化。而政府则以私人建筑所在区域对未来城市进行定位。

过渡性公共空间

由社区和商业机构引导,震后的公共空间干预措施受资本化的影响,进而产生了过渡性公共空间[13]。当地权力机关、商业机构和社区服务机构通过设定方案对过渡性公共空间提供支持,例如通过Vacant Spaces信托(LiVS)重建中央生活区。公共空间项目提供方包括:

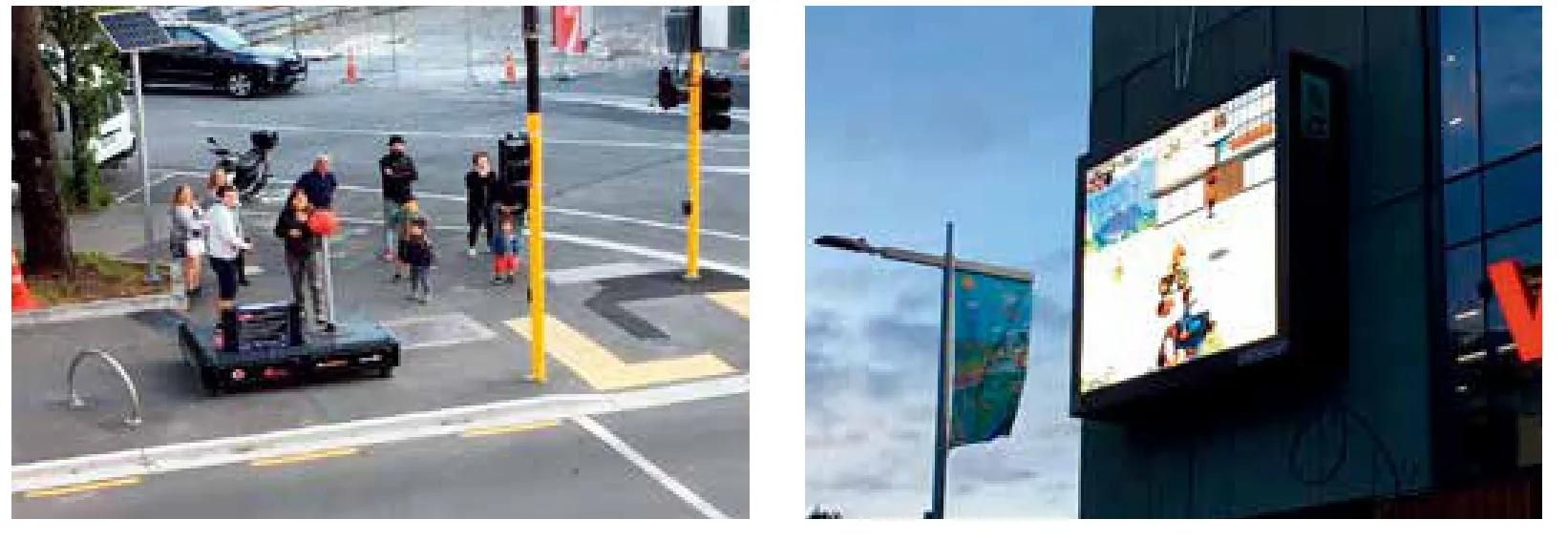

(1)Gap filler (临时性激活闲置场地的城市再生方案)。例如,使用跳舞机。这种机器包含室外舞台,带有投币式声光系统并通过洗衣机启动;也可使用超级街道露面,这是一种巨型室外悬挂在露面上的游戏系统,通过大型操纵杆和按钮进行操作(图10)。

(2)FESTA,过渡建筑节(免费的年度公众活动,旨在通过举办大型协作项目并执行城市干预行动来探索城市再生方案)。2012年的活动被称为Luxcity,包含照明系统安装活动。这些照明装置由新西兰周边的建筑专业学生设计制造(图11)。

(3)re-START(包含50个商业机构的超级购物中心,由建筑所属集团建造,并由基督城地震申诉信托基金和ASB银行的赞助商提供无息贷款)可以为基督城市中心提供临时性的零售区,吸引本地居民和游客返回市中心。

(4)瓦砾绿化行动 (志愿者们在损毁的商用建筑上设计、制造并维持公园和花园的风貌)。活动产生的效果让人印象深刻。在2011年至2014年期间,共有150个创意项目在100多个空置场地上实现了城市活力重生。每个纳税人的税款投资,以1:3的回报率获得了巨大成功[26]。

最终,社区居民通过装置装配和过渡性空间的构建实现了城市的重新塑造,为城市开发提供了全新的探索机遇。

图5 / Figure 5基督城中央街区和2015年空间设计指南中的中央街区绿化设想Greening of central city streets from Christchurch Central Streets and Spaces Design Guide 2015来源 / Source: 基督城市议会 / Christchurch City Council

图6 / Figure 6包含东部框架和Margaret Mahy家庭游乐场、零售商品协同定位以及司法管辖区的基督城中央商务区损毁(2013年)和重新开发(2018年)卫星图Christchurch Central Business District demolition (2013)and redevelopment (2018) including the East Frame and Margaret Mahy playground, retail co-location,and Justice Precinct来源 / Source: 谷歌地图/ Google Earth

4 城市设计让各个城区获得更好的项目投资

城市设计者鼓励不同类型的投资人群通过不同的集群投资方式对城市进行开发。例如,协同定位零售商店、创新和健康活动以强化投资活动的回报率。除政府和当地商业机构的投资以外,一些信托机构也推动着不少重大的重建项目,其中就包括re-START购物中心。该购物中心在基督城市中心推出弹出式购物区,吸引超过40家零售商加盟[27]。另外,还包括Isaac皇家歌剧院和艺术中心的翻新项目和Cardboard教堂与Epic高科技公司创新枢纽的震后重建项目。最近,新的零售区已在Columbo大街成立,让购物者们在时隔6年后重返故地。此处是城郊购物中心的重要零售区,在地震后大部分完好无损。

根据《基督城融合式政府办公大楼计划》的规定,15家政府机构和1,700名雇员已重新分配到4个中央商务区的建筑内办公。政府办公地点位于临近零售区、巴士站和其他中央城市设施的区域。订立的政府租约支出以杠杆的形式分布到私人开发建筑的重建计划之内。

司法和紧急服务区

从震后的经验学习中衍生的集群投资的例子之一,是对司法、警察、变更机构、消防机构、St John 急救机构、国家和地区公民防护机构的协同定位。其结果是,以固定配置的方式,通过降低资产和行政支出大幅提高了公共服务效率。这就要求在遭遇重大灾难期间,鼓励各方协同合作和创新来提供紧急服务。共享式通讯和紧急情况运作中心可以让各机构对紧急情况的协同响应变得更为简单。建筑符合IL4地震标准(重要等级4,遭遇自然灾难时保持运行状态)和新办公楼的绿色评级要求。建筑底层与城区公共场所一样对公众开放(图12)。

图7 / Figure 7 Margaret Mahy 家庭游乐场Margaret Mahy Family playground来源 / Source: Hugh Nicholson

图8 / Figure 8基督城东部郊区(2009年)和重建后(2018年)的对比图Christchurch eastern suburbs 2009 and retreat 2018来源 / Source: 谷歌地图/ Google Earth

图9 / Figure 9 Hereford 和 Cashel 大街之间 BNZ 中心的中央庭院Central courtyard in the BNZ Centre between Hereford and Cashel Streets 来源 / Source: Hugh Nicholson

图10 / Figure 10 Tuam大街上的超级街道楼面[25]Super Street Arcade in Tuam Street来源 / Source: Hugh Nicholson

医院区

坎特伯雷地震对城市的建筑和设备造成了巨大破坏,共有6,600~6,800名民众受轻伤(2011年10月ECAN 时评)。基督城的医院接待了220名因地震而遭受严重外伤的伤员。急救行动持续时间超过一周,之后转为伤员康复行动。由于医院某些区域也遭受了一定的破坏,医院相关人员也在同一时间予以疏散。但大部分时间内,医院还是保持开放状态以接纳伤员。

在健康领域,关键的抗逆和恢复问题是,使伤员免于建筑倒塌的风险;增加伤员的健康需求;对危险建筑内的人员进行疏散。基督城地区卫生局采用了一项有效的策略,使灾后的医疗资源得到合理分配,令患者可以尽可能地留在家里或社区内。这对医院系统进行了重新考量— 在整个城市内采用了更好的医疗设备。医院针对中央城区的在建建筑推出了新的紧急服务,为Burwood的医院派出新的专家服务团队,还在医院主楼的前门增设了一个门诊大楼。此项集群投资由新的地区医院网络进行记录备份。这些设施均采用IL4标准结构,确保在自然灾害期间保持持续运转。因此,新的医疗设施的投资针对终端用户,有效地使卫生系统保持运转。

校园重建

地震给163间中小学造成不同程度的影响,其中大部分闭园3周。90间学校在经过建筑结构核证完毕后重新开学。共有24份建筑的记录证明建筑须进行进一步评估,其中11座建筑损坏严重。整个城市建立了学习中心网络,为需要在家里进行远程学习的学生提供有效的资源和设备支持。截至2011年3月5日,共有4,879名基督城的学生在新西兰其他地区的学校登记入学。

目前,基督城的校园重建计划预期持续10年,其中包括:对13间学校作重新选址修建;10所学校原址重建;34所学校全部翻修;58所学校作中等翻修;一些小规模的校园作关闭或合并处理。新的建筑系统规定旨在接纳震后的转学学生,让校园在运营和管理方面更有效率,并执行“弹性学习空间”。此计划由于缺乏社区参与和社区内的学校认可而广受诟病。

图11 / Figure 11公共空间活动:2012年的LuxCity活动Public space activation: LuxCity Event 2012来源 / Source: 国家创意艺术和产业学院 /National Institute of Creative Arts and Industries

图12 / Figure 12司法和紧急服务区中心庭院Courtyard in centre of Justice and Emergency Services Precinct来源 / Source: Hugh Nicholson

5 城市设计无法解决的问题

可持续性建筑设计和基础设施

DCCP 提出建造更多的可持续性运输,包括修建一条从大学到中央商务区的轻轨,从而最终实现地区轨道网络和自行车道网络的连通。《中央城市规划草案》和《基督城中央城市重建方案》终稿均包含删除相关内容,其中包括要求改善环境指标和建筑包容性设计的规定,议会提出的重建项目财政激励措施,留待后续调查的关于交通和住宅的大部分规定(新自行车道除外)。

分散式排污系统

在西方城市对基础设施老化和延期维护的问题紧抓不放之时,基督城将编织出一张现代化的基础设施网络,这将使得基础设施整体能够满足重建计划的质量标准。更多的基础问题仍停留在选择何种系统将具有更高的抗逆力。基督城内分布着分散式供水系统,覆盖了整个城市内超过170口水井。相对而言,集中式废水处理系统可以在一家污水处理厂内统一处理几乎整个城市的污水。地震后人们发现,供水系统比污水处理系统更具抗逆力。供水系统能够迅速地重新启动运行,这是因为整个系统仍然能够保持其功能,受损部分可以通过修补得以继续使用。相反,集中式污水处理系统如果主要管道和处理池遭遇损毁,就将影响到整体功能,系统就必须关闭很长一段时间。这种基础设施的设计方式可以让系统在灾难期间依然可以持续运转。这是系统保持抗逆性的重要一环。

6 结 语

抗逆性在城市设计中的重要性正不断增加[28],这体现在城市恢复和灾难准备两方面。抗逆性实践必须得到执行,从而改变城市设计的实践方法。本文对抗逆性规划和传统城市设计实践之间的矛盾之处,通过一系列的案例研究进行了分析讨论。首先,采用集群投资可以更好地获得灾后的投资效益。这种趋势削弱了采用自由混合处理的传统城市设计原则的重要性。尽管自由混合处理通常是基督城重新开发策略的一个特征,但这种处理方式在城市设计者的应用选项中所占比重已经下降。它通过集群式医院、司法和紧急服务中心限制了既有的公共服务设施功能,并进一步约束了城市内零售商店分布的数量。具有针对性的抗逆力理论[29]建议,东部郊区红色地带可以永久性废弃,这是因为其他区域会不断遭受潮汐和洪水的侵袭。这就要求使用环保的手段实现抗逆性的未来城市拓展,而非采用现今的工程手段[30]。

城市设计在基督城重建的物理配置和环境品质的确定方面起主要作用。在震后重建工作的时间范围内,我们很容易看到这门科学的影响力。因此,这座城市本身就是一个很好的案例,可以用来进行目前城市设计方法和抗逆性思考在城市恢复中的案例研究。其他的城市设计过程更为缓慢,设计过程中所进行的调整繁杂不堪。尽管针对性的抗逆性策略应该得到采用,但并非所有的创新举措都已得到实施,有些尚未采用的措施也代表着与未来机遇失之交臂。尽管如此,基督城人民在抗逆性和城市设计方面取得了众多成果。

ORIGINAL TEXTS IN ENGLISH

The Role of Urban Design in Re-building Christchurch

Diane Brand, Hugh Nicholson

1 Urban Design and Resilience De finitions

The phrase “urban design” emerged in the mid-20th century at a conference on modernism hosted by the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 1956[1]. American urban planner and theorist Edmond Bacon defined design in the context of urban design by distinguishing between the city as an “act of will” and the city as a “grand accident”[2]and this definition still encapsulates the essence of the discipline in an elegantly time and agenda neutral manner. Changes in the practice of urban design have been wide ranging in the latter half of the twentieth century and in the new millennium. In chronological sequence urban design has engaged with the industrial and post-industrial urban and suburban condition, the economic, cultural and spatial impacts of globalisation, the inequalities and contested territories that cities generate, and sustainability, climate change and the impact of natural disasters on contemporary urban communities. As a result successful urban design now engages professionals from many sectors including design, construction, science, economic and social services, with the aim of establishing communities,which are deeply connected to economically and socially sustainable landscapes.

The term “resilience” is now part of the urban design equation. Resilience means different things across a variety of disciplines, but all definitions are linked to the ability of a system, entity, community or person to withstand shocks while still maintaining its essential functions stress[3]. Resilience also refers to an ability to recover quickly and effectively from catastrophe, and a capability of enduring greater stress[4,5].

Twenty- first century disaster literature is primarily concerned with the negative impacts of climate change, and divides into the documentation of recent disasters such as Hurricanes (Katrina and Sandy), Tsunamis (Indian Ocean and Sea of Japan),Earthquakes (Chile and Haiti), and the discussion offorward community planning initiatives which investigate mitigation and adaption. The literature encompasses multiple scales of the urban environment, with spatial planning theorists[6]comparing scenarios of urban in fill, urban extension and new settlement as alternative adaption strategies, and urban planners and designers[7]interrogating the urban social and economic and infrastructural outcomes of recent reconstructions. Bergdoll[8]in Manhattan and Roettger and University of Virginia School of Architecture[9]in New Orleans have curated design solutions and adaptive architectures and settlement strategies for tidal inundation, and Aquilino[10]has interrogated the pragmatics of rebuilding after floods, earthquakes, tsunamis and fires, with particular attention to building designs,construction processes and materiality.

The intersection of urban theory and resilience theory has been investigated by Godschalk[11]who discusses resilient cities in relation to natural hazards and terrorism, and Wu and Wu[12]who position classic urban design theory within resilience literature and posit areas of tension in future sustainable design practice around the dialectic of stasis and change.

A number of writers have researched speci fic issues related to urban, landscape and building design in the aftermath of the Canterbury earthquakes.Bennett et al[13]document and debate the recovery process after the Christchurch earthquakes.Swaffield[14]interrogates the kinds of places and cultures that have evolved in a rebuilt Christchurch as a result of the nexus between directive central government processes and spontaneous bottom-up community projects. Wesener[15]has described in more detail the resulting transitional community-initiated open spaces in Christchurch.Jacques et al[16]have evaluated the performance of the Christchurch hospital system and developed a method which can predict the future performance of hospitals in terms of seismic preparedness strategies. However a gap remains in the literature with respect to the potential contribution that urban design can make to urban resilience planning,which this paper aims to address through a discussion of the case study of Christchurch, New Zealand.

This paper will discuss how urban design and resilience principles and processes have informed the Christchurch Re-build since the devastating earthquakes of 2010 and 2011 (Figure 1), and will focus on four propositions: that urban design delivered a post-disaster vision of a low-rise city green city;that urban design delivers a resilient public realm;that urban design delivers better project investment from multiple sectors; and finally what urban design hasn't been able to deliver. Each proposition will be discussed in terms of actual case studies from the reconstruction of the city of Christchurch over the last seven years.

2 Urban Design has Delivered a Postdisaster Vision of a Low-rise City Green City

Public consultation process to create a vision:Share an idea

As part of developing the Council's Draft Central City Plan (DCCP) (Christchurch City Council,2011)[17]an extensive public consultation exercise(Share an Idea) was undertaken with the people of Christchurch within three months of the February earthquake to help shape the recovery plan for the central city. The Share an Idea website generated 58,000 hits and engaged the public in four key areas: move (transportation), market (business),space (public place and recreation) and life (mixed uses), and the campaign used traditional and social media networks. This was followed by an interactive expo with more than 10,000 visitors, an international speaker series, 10 community workshops,more than 100 stakeholder meetings and a 48-hour design challenge for five selected sites. Public participation generated 106,000 ideas over six weeks and these informed the development of the Draft CCP[18]. Share an idea became the basis for developing a shared vision for the city and resulted in a broadly agreed direction to measure projects against. This type of public consultation and community engagement should ideally be to be an iterative process resulting in an ongoing discussion.The two principal outcomes of the consultation process were the vision for a sustainable low-rise city in a green setting.

Low-rise city

A strong public resistance to tall buildings emerged in the aftermath of the earthquakes in response to the highly visible building failures and the ever present urban search and rescue activity. A bold initiative embedded in the urban design proposals in the Draft CCP was a reduction in height limits to 28 metres or seven storeys (the same height as Washington DC), with a 21 metre road wall height (Figure 2). This combination provides a 1:1 cross-sectional proportion giving a good sense of enclosure to the street corridor while allowing the sun to reach the opposite side of the road in midwinter.

Economic impact studies indicated that given the geotechnical conditions in central Christchurch,buildings of more than 6-8 stories required a more expensive structural system, making 6-8 stories was the optimal return on construction investment.The 28 metre height limit was adopted into Draft Central City Recovery Plan with unanimous support from Council. An office demand study indicated that the expected uptake of office floor space in central Christchurch could be accommodated with an even spread of 28 metre buildings across the central business district or in a small number of towers. The Christchurch Central Recovery Plan was approved with the 28 metre height limit which would spread the rebuild across a wider area of the CBD to create a vibrant and prosperous mix-use central city.

Green city

Several opportunities emerged in the new plans to make Christchurch a greener city. Both the DCCP and the Christchurch Central Recovery Plan(CCRP)[19]set out to provide an enhanced network of green open spaces based around the Ōtākaro Avon River and Cathedral Square. From a space lined with carparks which the city turned its back on, the Ōtākaro Avon River has been recast as the primary public space in the city (Figure 3). In partnership with Ngai Tahu, the indigenous first people, the redevelopment includes a river promenade,a number of significant artworks, and extensive native riparian habitats.

Traditionally Cathedral Square has been a paved space which originally included roads and was the main point of departure for trams and subsequently buses. Largely pedestrianised in the late 1990s with slow vehicle access around some of the edges, the space was unloved by the public. Feedback from Share an Idea was strongly in favour of creating a greener space in the centre of the city. While the Otakaro Avon River redevelopment has been largely completed, greening Cathedral Square is still in the planning stages (Figure 4).

The Accessible City chapter was a late addition to the CCRP and included a range of measures to improve the quality of central city streets including slowing traffic to 30 kilometres per hour and improving pedestrian and cycling facilities. As part of these works there has been a focus on replacing more than 500 on-street carparks with wider footpaths, street trees and rain gardens. Encapsulated in the Christchurch Central Streets and Spaces Design Guide the completed streetscapes have created greener and more sustainable central city spaces(Figure 5)[20].

Compact city

In terms of broad urban design objectives both the DCCP and the Christchurch Central Recovery Plan (CCRP)[19]set out to rebuild a more compact intensive low rise commercial core, to increase the number and density of inner city residents, and to promote mixed use developments in areas surrounding the core (Figure 6). The redevelopment clustered around a set of core projects seeded by government, which were designed to attract investment and rebuilding in the CBD. These included a metrosports hub, a convention centre, a central library and a new bus exchange.

The DCCP adopted an integrated approach to recovery which incorporated a wide range of projects and implementation tools. The vision balanced incentives and regulation to deliver major catalyst and public space projects, alongside sustainability,housing, arts and transport projects. The CCRP is focused more deliberately on National government priorities providing a regulated vision embodied in a range of catalyst projects which involve rebuilding critical public and economic infrastructure such as the hospital and the convention centre.

East Frame

While the DCCP proposed using built form planning regulations to further promote a compact commercial core, the CCRP adopted a far more interventionist approach by establishing a “green frame”, reinstating the 19th century parklands around the city centre (which were originally proposed in the Jollie Plan in 1850)[21]and compulsorily acquiring large areas of land surrounding the core. The east frameis being used for a comprehensive medium density residential development,with a north south linear park approximately 30 metres wide through the centre. The south frame will not be compulsorily acquired due to increasing land costs but a framework of public laneways and a central city school has be established in tandem with built form planning regulations to limit development potential. The East Frame was designated for comprehensive residential development with more than 900 apartments. The delivery of these was negotiated with single developer to ensure an integrated development that incentivises long term bene fits for city rather than short term pro fits.A “Design Framework” forms part of agreement together with a set of urban design controls. This represents a partnership approach to rebuilding the city between Fletchers, central government and the local council, with the buildings being provided by the developer and the streetscape and public realm being delivered by the Crown and the Christchurch Council.

Metropolitan Playground

At the Northern end of the East Frame the Crown and the Council have funded the development of an important public realm initiative called the metropolitan playground or the Margaret Mahy Family Playground named after New Zealand's famous children's writer (Figure 7). It has become anchor for rebuild which attracts thousands of children and their families during the day and in the evenings it has become a safe location where teenagers can hang out.

Eastern suburbs retreat

Decisions to affect a strategic retreat from vulnerable areas of residential housing have vacated swathes of land along the lower reaches of the Avon River (Figure 8) and in steep and exposed parts of the Port Hills leaving them derelict and maintained as mowed grass with the trees still showing the former lot patterns in a form of suburban stasis. These areas are generally surrounded by existing houses and although many of the streetsand services within the red zone have been signi ficantly damaged they still constitute important con-nections within a fractured urban fabric. Currently planning and public engagement on the future of this land is underway, managed by a public company Regenerate Christchurch, half owned by the Crown and half by the Council. Questions which are still to be answered include who will own the“red zone” land, what it will be used for, and how it will be governed.

As a result of the devastation of the earthquakes,Christchurch will become a greener city in the future. The CCRP has reinstated the parklands around the CBD and the necessary retreat from the Avon River will create an ecological and flood corridor along its banks. Much potential exists for food production or recreational use of the Eastern suburbs land that has been red zoned. The quantity of green space in public ownership, both adjacent to the city centre and in the suburban land between the CBD and the coast has increased dramatically.These possibilities have been captured by extensive community consultation and responsive planning strategies which evoke the landscape and settlement history of Christchurch and facilitate a more compact, sustainable and liveable city of the future.

3 Urban Design Delivers a More Resilient Public Realm

The grid, laneways and open spaces

Christchurch's planned grid and generous innercity open spaces provided an effective and resilient urban structure after the earthquakes in 2010 and 2011, con firming the observations from other cities[22,23]. The historic street grid provided flexibility and alternative options to cope with limited street closures, both as part of the emergency response and during subsequent building demolition and construction phases. The inner city parks provided refuge and shelter immediately after the earthquakes and were used as a base for the international search and rescue operations (Nicholson 2013)[24].

Prior to the earthquakes one of the most interesting and vibrant parts of Christchurch's urban structure were the laneways within central city blocks. Originally these were built to provide service access,particularly to industrial buildings to the south of the city centre. With the decline of these industries the warehouses were converted to a mixture of retail, hospitality and residential uses providing vibrant and highly popular precincts. Many of these areas were either destroyed by the earthquakes or are tied up in insurance claims (e.g. Lichfield Lanes and Sol Square). Both the DCCP and the CCRP have sought to recreate these secondary elements of urban structure within the formal grid. In the retail precinct there has been a requirement to develop Outline Development Plans (ODPs) for a minimum of half a block (or 7500 m2) before lodging a resource consent. One of the requirements of the ODPs is to provide north-south laneways. With the majority of ODPs now in place therehave been a series of laneways and courtyards (Figure 9) created throughout the retail precinct - not for service access but to encourage public access and to support retail and hospitality uses. Similarly, the South Frame and a number of the major anchor projects,including the Justice and Emergency Precinct, the Innovation Precinct and the Convention Centre,have incorporated public laneways and courtyards into their design. The city is seeing the conscious recreation of a traditional urban form that characterized Christchurch pre-earthquake as part of recreating the city's identity.

Contradicting that evocation of the traditional city is the predominance of contemporary commercial building typologies (with large open floor plates)which are creating a new super grain to the urban fabric central city fabric, and which privatise what would traditionally have been the public realm,since the land on which the new lanes and courtyards sit have an private existing use status (i.e.they are not designated as public streets). This is the reality of real estate development in a modern city recovering from natural disaster off a low public investment base. The essential issue in the Christchurch rebuild is the fundamental change in both the use and scale of the new and fast repeating typologies of commercial and residential buildings where the government is relying on the private sector to deliver the future city.

Transitional Public Space

This capitalised on the public realm interventions post-earthquake led by communities and business which provided transitional public space[13]. These were supported by local authorities, businesses,and community agencies through initiatives such as Rebuild Central and Life in Vacant Spaces Trust(LiVS).Public space project providers included:

(1) Gap filler (an urban regeneration initiative that temporarily activated vacant sites) for example Dance-o-mat which consisted of outdoor dance venue with a coin operated sound system and lights operated via a washing machine, and Super Street Arcade, a giant outdoor arcade game system operated by a giant joystick and buttons (Figure 10[25]).

(2) FESTA, Festival of Transitional Architecture (a free, annual public event that explores urban regeneration through large scale collaborative projects and urban interventions). The 2012 event called Luxcity comprised of light installations designed and built by architecture students from around New Zealand (Figure 11)

(3) re-START (a 50 business container mall built by a property and building owners group, with an interest free loan from the Christchurch Earthquake Appeal Trust and sponsorship from the ASB Bank)providing a temporary retail precinct for central Christchurch which attracted both locals and tourists back to the city centre.

(4) Greening the Rubble (volunteers who design,construct and maintain parks and gardens on the sites of demolished commercial buildings)

The results have impressive with more than 100 vacant sites activated 450 times with 150 creative projects between 2011 and 2014. This success is re flected in a three to one return on investment for every ratepayer dollar spent[26].

As a result the city has been reshaped by these community driven installations and transitional spaces which have allowed the exploration of new opportunities for urban development.

4 Urban Design Delivers Better Project Investment From Multiple Sectors

Urban Designers have encouraged the development of use clusters implemented by groups of different kinds of investors. For example the co-locating of retail, innovation and health activities designed to enhance the benefit of any single investment.In addition to investment by government council and local business, a number of signi ficant rebuild projects have been run by Trusts. These include the ReStart Mall which has provided a pop-up shop-ping area in central Christchurch involving more than 40 retailers at its peak[27]the refurbishment of the Isaac Theatre Royal and the Arts Centre,the construction of Cardboard Cathedral and Epic innovation hub for hi-tech companies displaced by the earthquakes. A new retail precinct has recently been completed in Columbo Street to bring shoppers back to the centre after six years of the retail dominance of suburban malls which were largely unaffected by the earthquake.

Fifteen government agencies and 1,700 staff have relocated into four CBD buildings as part of the Christchurch Integrated Government Accommodation Programme. The government offices are located close to retail precinct, the bus interchange and other central city facilities. Guaranteed government tenancies have leveraged the rebuilding of these privately developed buildings.

Justice and Emergency Services Precinct

An example of clustered investment which has been directly derived from learnings after the earthquake is the co-location of Justice, Police,Corrections, the Fire Service, St John Ambulance and national and local Civil Defence agencies. The result will be greater public service efficiencies through reduced property and administration costs in a con figuration which encourages collaboration and innovation in the delivery of emergency services during large scale disasters. Shared communications and a shared emergency operations centre will make coordinated responses to emergencies much easier to achieve. The building meets IL4 seismic standards (Importance Level 4 keep operating through natural disasters) and the green star rating required for new offices. At ground level the site is permeable to the public and reads like a city block (Figure 12).

Hospital Precinct

The Canterbury earthquakes inflicted large scale damage to buildings and equipment across the city. Between 6,600 and 6,800 people were treated for minor injuries (ECAN Review October 2011),and Christchurch Hospital alone treated 220 major trauma cases connected to the quake. Rescue efforts continued for over a week, then shifted into recovery mode. Christchurch Hospital was partly evacuated due to damage in some areas, but remained open throughout to treat the injured.

For the health sector, critical resilience and recovery issues are: balancing patient care against risk of building failure; increased health demands from injuries; and the evacuation of dangerous buildings. The Christchurch District Health Board has developed a compelling strategic vision for the post disaster future of healthcare centred dedicating resources to helping patients stay in their homes and communities for as long as possible. This has involved rethinking the hospital system -and new provision of enhanced facilities across the city. A new acute services building under construction in central city, a new specialist services hospital in Burwood, and a new outpatients building at the front door to main hospital building. This cluster is backed up by a network of new regional hospitals.These facilities are all IL4 structures -which can keep operating through natural disasters. The net result is an investment in new healthcare facilities which will herald a stronger more efficient health system focused on the end users.

Schools Rebuild

One hundred and sixty three primary and secondary schools were affected by the earthquake, most of which were closed for three weeks. Ninety schools had full structural clearance and were able to reopen. Twenty four had reports indicating further assessment and 11 were seriously damaged.Learning hubs were established throughout the city to provide resources and support for students needing to work from home. By March 5th 2011, a total of 4879 Christchurch students had enrolled in other schools across New Zealand.

There is now a comprehensive ten year programme for rebuilding Christchurch schools. This includes:Thirteen new schools on new sites; Ten rebuilt schools on existing sites; 34 schools fully redeveloped; 58 schools moderately developed and number of smaller schools have being closed or merged. The new system of building provision has been aimed at accommodating changed student rolls after earthquakes, providing greater efficiency in procurement and operations, and implementing“flexible learning spaces”. The programme has attracted wide criticism for the lack of community engagement and lack of recognition of the role schools play as community foci.

5 What Urban Design wasn't able to Deliver

Sustainable building design and infrastructure

The DCCP proposed more sustainable transportation systems, including a light rail system from the University to the CBD which would eventually connect into a regional rail network, and a network of cycle ways. Major changes between the Draft CCP and final CCRP included the removal of the regulations requiring improved environmental performance and inclusive design standards from buildings, the removal of the financial incentives for rebuilding proposed by the Council, and the removal of the majority of the transport and residential provisions (apart from the new cycleways)pending further investigation.

De-centralised sewage system

While most western cities are grappling with issues of deferred maintenance and ageing infrastructure,Christchurch will have a modernized infrastructure network which will have been repaired to an acceptable standard by the end of the rebuild programme. More fundamental questions remain about what kind of system is more resilient. Christchurch has a decentralized water supply system with more than 170 wells spread across its urban area, in contrast to its centralized wastewater system where almost all of the city's sewage is treated at one treatment plant. In the aftermath of the earthquakes the water system proved to be more resilient than the wastewater. It was able to start operating again more quickly as parts of the system remained functional and could be patched to support damaged areas. In contrast, the centralized wastewater system suffered damage to main sewer lines and to the treatment ponds themselves, effectively closing down the entire system for a longer period. Designing infrastructure so that parts of the system can continue to function independently in a disaster would seem to be an important step towards resilience.

6 Conclusion

Resilience is of increasing relevance to the design of cities[28], both in terms of recovery and in disaster preparedness. Resilience practice is set to modifying urban design practice and the case study above illustrates a couple of emerging contradic-tions between resilience planning and traditional urban design practice. The first is the use clustering for better post-disaster investment. This trend undermines the traditional urban design principle of liberally mixing uses. While mixed use is a feature of the Christchurch redevelopment strategy in general, the range of uses in the urban designers menu has been reduced by circumscribing an already limited palette of public service uses with the clustering hospital,justice and emergency services functions, and further constraining the quantum of distributed retail across the city. Targeted resilience theory[29]suggests that the eastern suburbs red zone will be permanently abandoned for settlement as will other areas subject to repeated liquefaction and flooding, leading to an ecological approach to the resilience future urban expansion rather than an engineering approach which has been used to date[30].

Urban design has played a major part in determining the physical configuration and environmental quality of the Christchurch re-build. It is easy to see the extent of the discipline's impact due to the short post-earthquake construction timeframes, so the city is an ideal case study of the impact of current urban design and resilience thinking on urban recovery. Elsewhere urban design processes occur at a slower pace and adjustments in the design process happen in a more fluid and incremental way. Not all initiatives have been implemented and some gaps represent lost opportunities for the future, while targeted resilience strategies are required moving forward. However much has been achieved in terms of resilience and urban design for the people of Christchurch.