婴儿猝死综合征研究现状

2018-02-28朱金秀卢喜烈鲁楠何卓乔严静怡谭学瑞

朱金秀 卢喜烈 鲁楠 何卓乔 严静怡 谭学瑞

婴儿猝死综合征(sudden infant death syndrome,SIDS)是婴儿死亡的重要原因。由于缺乏明确的病理生理学机制,死亡后才能明确诊断是SIDS的突出特点,其诊断依据建立在排除基础上。通常情况下,婴儿在睡眠过程中被发现死亡。突然发生的、不明原因的、健康婴儿的死亡显然是家庭的悲剧。即使经过深入调查,包括详细的尸检和所有辅助检查,如组织学、微生物学、病毒学、毒理学,仍有约70%~80%的婴儿猝死是无法解释的[1]。2013年美国心律学会(HRS)、欧洲心律学会(EHRA)、亚太心律学会(APHRS)专家共识将不明原因的婴儿猝死纳入遗传性心律失常范围[2]。SIDS是发达和发展中国家重要的公共健康问题,但目前尚缺乏有效的筛选流程和新生儿/婴儿心电图特征与SIDS对应的临床流行病学研究资料,以及已知的遗传性心律失常致病基因与SIDS之间的机制研究。我们针对上述内容综述如下。

1 猝死定义

猝死在临床上定义为看似健康的人在短期内(一般从急性症状开始不超过1 h),自然或意外死亡[3]。85%以上的猝死由心脏原因导致,即心源性猝死(sudden cardiac death,SCD),每10万人中约有50~100人由SCD导致死亡[4]。35岁以下的SCD患者, 24%~31%由冠状动脉疾病导致,17%~37%与心肌病相关,31%~35%肉眼和组织学检查无法确定病因,经DNA检测尸检阴性的死亡病例中约53%存在已知的遗传性心律失常[5]。

2 婴儿猝死综合征定义

看似健康的婴儿在睡眠中(包括晚上、早晨或午睡后)突然意外死亡的现象称为SIDS或者“婴儿猝死”。自1969年西雅图第二届婴儿猝死病因国际会议上提出婴儿猝死的概念,SIDS的定义被不断补充和更新[6-7]。综合流行病学危险因素、病理特征以及辅助实验结果后,Krous等[8]定义SIDS:年龄<1岁的婴儿在睡眠过程中突然意外死亡,经过深入调查仍然无法解释其原因,调查包括完整的尸检、死亡现场检查和临床病史回顾。此定义强调猝死发生于睡眠状态,并需要对死亡情况进行评估,是目前应用最广泛的定义。

3 婴儿猝死综合征流行病学

连续随访5年的研究结果显示,1~19岁青少年群体中,1~2岁幼儿发生SCD的概率最高[9]。分年龄段研究猝死流行病学特征有利于制定个性化诊断和预防策略。不同国家、族群、性别以及一年中不同季节SIDS的患病率均有差异,活产婴儿中总发病率约0.5‰~2.5‰[10-11]。时至今日,SIDS仍是美国以及其他发达国家婴儿死亡的主要原因,约占婴儿总死亡率的33%[12]。在我国,SIDS约占婴儿总死亡率的11.9%,仅次于肺炎和先天畸形[13]。

婴儿出生后1~2周内 SIDS较少见,90%的SIDS发生于3周之后,第3周~4个月为高峰,6个月后罕见,平均死亡年龄(2.9±1.9)个月,约60%为男婴[14-15]。双胞胎SIDS的发生率高于单胎(1.3‰vs. 0.7‰),这种现象在某种程度上反映了双胞胎早产儿和低体质量儿的发病率更高[16]。

4 婴儿猝死综合征危险因素及可能机制

SIDS相关的危险因素,一方面包括环境诱发,例如俯卧睡眠、睡眠环境、高温、季节以及尼古丁暴露;另一方面是尚不清晰的生物因素,可能涉及心脏功能、脑干传导功能、呼吸调节功能和免疫系统的基因[11-17]。

俯卧睡眠是已经确定的重要的SIDS危险因素,与窒息相关的危险因素还包括床上覆盖物以及和监护人同床睡眠[18-19]。吸烟是SIDS的独立危险因素,母亲在孕期吸烟或婴儿出生后暴露在烟雾环境中均与SIDS相关[20-21],在智利约1/3的SIDS由产前吸烟导致[22]。乙醇与SIDS的相关性尚存争议,Blair等[23]研究发现,与对照组相比,SIDS组的母亲饮酒率高,但在矫正了吸烟等混杂因素后两组间无差异。然而,McDonnell-Naughton等[24]研究结果显示,SIDS患儿的母亲在怀孕期间比对照组饮酒率更高、饮酒量更大。另有研究发现,怀孕期间每天摄入400 mg及以上咖啡因(相当于4杯以上咖啡)增加SIDS的风险[25],但也有研究者认为是存在其他混杂因素导致[26]。此外,婴儿看护中心具有较高的SIDS发生率,发生机制尚不明确,有研究者认为可能与睡眠不足导致婴儿更深层睡眠和觉醒障碍有关[27-28]。

上述SIDS的危险因素,如俯卧睡眠、头部覆盖、共用床位、吸烟、饮酒和咖啡因都是可以避免或改变的。然而,“三重风险模型”中考虑的风险因素并非如此。近年来研究者提出众多关于SIDS死亡原因和机制的假说,包括炎症、血清素异常和代谢紊乱。最具影响力的假说是Filiano等[29]提出的“三重风险模型”,即SIDS由多种因素导致和诱发,其发生和发展机制包括内源因素、外源因素和诱发因素(图1)。例如,胎儿在母体发育过程中,可能由于孕妇吸烟而形成了一个易感婴儿,这类婴儿出生以后的发育关键时期如遇到炎症等外源性因素的刺激,则可能大大增加SIDS的风险。

三重风险模型提出后,多种内源、外源因素被发现与SIDS相关[19]。内源风险因素定义为“影响易感性的遗传或环境因素”,包括非洲裔美国人、男性、早产(<37孕周出生)、低体质量和孕期吸烟或饮酒等,外源风险因素定义为“死亡时可能会增加易感婴儿猝死风险的物理应激”如上呼吸道感染、高温环境等。三重风险模型强调了SIDS的综合性,遗传倾向、生长发育过程中的已知危险因素和环境因素(包括病毒和细菌)都在SIDS中发挥作用。大量假说主要集中在呼吸或心功能的稳态控制异常,但SIDS的根本原因仍不清楚。

图1 婴儿猝死综合征的三重风险模型

5 遗传易感性

近年来,与SIDS相关的基因突变和多态性受到广泛关注,与SIDS相关的基因包括参与自主神经系统早期发育的基因(PHOX2a,RET,ECE1,TLX3 和EN1)、尼古丁代谢酶、参与免疫系统、能量产生、血糖代谢、体温调节和线粒体活性的基因等[30]。

脑干中的5-羟色胺(5-HT)网络在SIDS研究领域中备受关注,血清素是神经和免疫系统相互作用的重要媒介,而大脑可能是SIDS患儿免疫反应导致脑脊液中IL-6水平升高引发致死机制的靶器官。炎症是SIDS中不可忽视的诱因,超过40%的婴儿在发生猝死的前两周内有轻微上呼吸道感染症状。Blackwell等[31]发现几种促进炎症反应失控的基因多态性,特别是导致抗炎细胞因子白细胞介素10(IL-10)失活或促进细胞因子IL-1β和IL-6过表达的基因多态性与对照组比较增加SIDS的发病率。SIDS与血管内皮生长因子(vascular endothelial growth factor,VEGF)基因多态性的关联性被相继报道,研究发现妊娠期糖尿病患者的脑脊液中VEGF水平显著升高,提示组织缺氧可能在SIDS中起重要作用[32]。其他炎症过程可能位于消化道、神经系统和血液中[10],不受控制的炎症介质的释放以及其毒性是SIDS发生的重要因素。常染色体隐性遗传病中链酰基辅酶A脱氢酶(MCAD)缺乏导致的脂肪酸氧化障碍,也是SIDS的致病基因,约7.3%的SIDS由MCAD遗传缺陷导致。基因组学研究中主要的限制是不同种族之间的遗传变异,不同研究结果间很难进行比较。

6 遗传性心律失常与婴儿猝死综合征

青少年群体的猝死通常由原发性心律失常综合征引起,死亡原因为电节律紊乱而非机械泵衰竭[33]。潜在的遗传基础是必要条件,包括结构性心脏病和遗传性心律失常[34-35]。常见的遗传性心律失常包括长QT综合征(LQTS)、儿茶酚胺敏感性多形性室速(CPVT)、Brugada综合征(BrS)和短QT综合征(SQTS)。SIDS为排除性诊断,需排除结构性心脏病,因此推测SIDS多由遗传性心律失常诱发电紊乱导致[36]。

虽然SIDS是多因素共同作用的结果,然而心电图和分子生物学研究已经阐明了它与遗传性心律失常之间的关联性[37-38]。继Arnestad等[39]研究发现约12%的SIDS由LQTS导致后,BrS、CPVT以及SQTS都被列为SIDS可能的致死原因[40-41]。截至目前已发现数十个基因突变与上述离子通道疾病相关(表1),其中4个最常见:SCN5A、KCNQ1、KCNH2、和RyR2,分布如下:LQTS (KCNQ1 40%,KCNH2 30%和SCN5A15%),BrS(SCN5A25%),CPVT(RyR2 50%),SQTS(KCNQ1 30 %、KCNH2 20%)[42]。遗传性心律失常疾病相关的基因[43]见表1。

表1 遗传性心律失常疾病相关的基因

6.1 长QT综合征

LQTS患病率约1/2000,是编码心脏离子通道或调节其活性的蛋白质基因突变导致的与心肌动作电位离子控制有关的常染色体显性遗传性疾病,心室复极时间延长,室性心律失常和SCD风险增加是LQTS的显著特点[44]。LQTS至少有16种基因亚型,体表心电图大多表现为QT间期延长,研究结果证明,新生儿心电图QT间期筛查对SIDS以及青少年、成人的SCD风险评估具有重要价值,婴儿期间经历心脏骤停的LQTS患儿,在未来十年中是心脏骤停甚至猝死的高风险人群[45-46]。Yoshinaga等[47]研究了1058名从出生至1岁婴儿的QT间期变化,研究结果显示出生后6~11周是新生儿-婴儿生长发育过程中QTc间期最长的年龄段。这恰巧与SIDS流行病学特征基本吻合,进一步佐证QT间期延长与SIDS的相关性。然而,约25%的LQTS基因阳性患者QT/QTc间期正常,但与其他LQTS基因型阴性的兄弟姐妹相比,危及生命事件依然增加。因此,传统的QT/QTc间期测量可能会遗漏潜在的LQTS患者[48]。T波形态标记作为补充筛查工具,可进一步完善心电图对LQTS患者的筛查,并在增加敏感性的基础上根据不同形态区分亚型[49]。

6.2 Brugada综合征

BrS是一种常染色体显性遗传性疾病,表型多变,外显率低于LQTS,患病率0.01%~1%,其中亚裔人群患病率最高,是东南亚健康青年死亡的主要原因[50]。BrS特点是无心脏结构异常的患者心电图右胸导联ST抬高[51](图2),突然死亡可能是BrS的首发症状。约25%的BrS与SCN5A基因突变相关,另外17个基因变异体仅占确诊病例的5%,70%的BrS不能确定基因突变类型[51]。较少有人在婴幼儿人群关注BrS,最近的研究发现BrS和SIDS具有相同的易感突变基因GPD1L和SCN1B/SCN1Bb,两者均可致心脏钠离子通道功能丧失,诱发SCD[52-53]。心电图检查对BrS有重要的诊断以及预警意义。研究发现,BrS患者在Ⅰ导联存在宽大的S波、碎裂QRS波、早期复极均是预测BrS患者恶性室性心律失常、心脏性猝死的独立危险因素[54-56]。

图2 Brugada波心电图表现

6.3 儿茶酚胺敏感性多形性室速

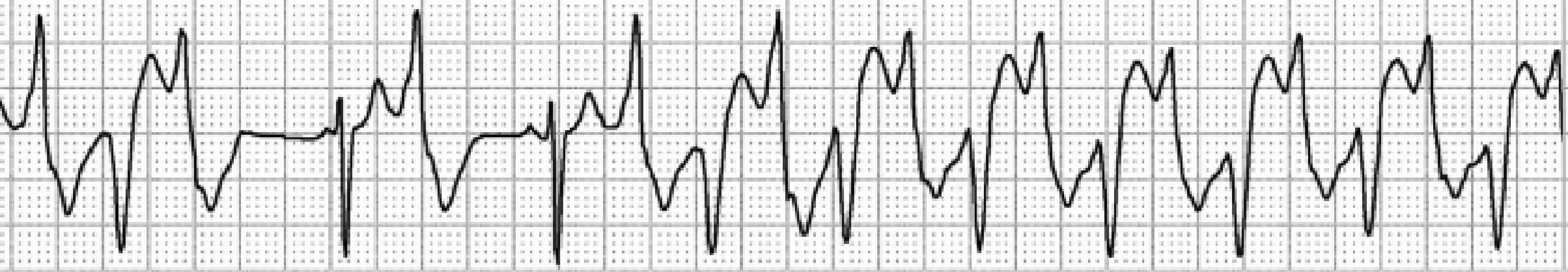

CPVT是常染色体显性遗传性疾病,心脏性猝死往往为第一临床表现。CPVT发病率约1/10 000,但发病率可能被低估,Jiménez-Jáimez等[57]发现14%的尸检阴性患者与CPVT相关基因突变有关。心脏RYR2(60%)受体与参与钾离子通道编码的KCNJ2(5%~10%)突变是导致CPVT的主要分子基础[58]。双向型、多型室性心动过速是CPVT的典型心电图表现[59](图3)。约30%的CPVT在儿童期发病,心电图在小儿CPVT的诊断中具有重要价值[60]。

图3 儿茶酚胺敏感性多形性室速的心电图表现

6.4 短QT综合征

与LQTS相反,SQTS以心脏复极加速,心电图QT间期缩短为特征,但同样增加心脏性猝死风险。目前用于确定SQTS诊断的QT间期低限不同,普通人群中QTc<360 ms者约2%,<340 ms者约0.5%,而<300 ms者仅0.003%[61-62]。与LQTS相比,SQTS患者的心律失常更易发生于安静状态,这与SIDS的发病状况类似[63]。

6.5 早期复极

早期复极与BrS有相似的心电图表现,定义为心电图至少在两个相邻导联伴随J点抬高(≥0.1 mV,除V1~V3导联)出现J波、QRS末端切迹或者R波降支顿挫[64-65]。早期复极与房性、室性心律失常和心脏性猝死风险增加有关,目前研究范围尚未涉及婴儿群体,但研究发现早期复极常伴随LQTS、BrS、SQTS疾病出现,并且进一步增加心律失常事件的风险[66]。

虽然研究者们一直在探索,迄今为止还缺乏SIDS有效筛查手段。基因筛查受实验室条件、经济条件等限制,很难在新生儿中广泛应用。成本低廉、可靠有效的检测手段是SIDS筛查、早期干预降低死亡率的关键技术。心电图描记术简单、无创、廉价、易行,尤其对遗传性心律失常诱发的SIDS有重要的筛查、预警和诊断意义。少有人跟踪到新生儿-婴儿-幼儿期的连续心电记录,而新生儿-婴儿阶段是母婴共体向独立个体循环模式转变的关键时期,血流动力学以及心脏功能发生巨大变化。因此,新生儿-婴儿心电图具有复杂多变性,这些复杂变化诠释着胎儿脱离母体后适应循环系统血流动力学的动态变化、胎儿和新生儿心肌的不同生理特征以及在以后的生长发育中心脏在胸腔的位置、方向变化[67]。然而,心电图检查并非新生儿常规检查项目;其次,缺乏基于心电学的SIDS高危人群的筛查预警指标。新生儿复杂多变的心电图现象中可能蕴含着SIDS有关的特征性改变,特别是与SIDS有重要相关性的遗传性心律失常性疾病的心电图学特征。通过流行病学研究,发现、提取、分析、总结这些心电图学特征,建立基于新生儿心电图的早期SIDS高危婴儿筛查指标体系对于早期预防、干预SIDS有科学和实践价值。

[1] Evans A, Bagnall RD, Duflou J,et al.Postmortem review and genetic analysis in sudden infant death syndrome: an 11-year review[J]. Hum Pathol, 2013, 44(9):1730-1736.

[2] Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M,et al.HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes: document endorsed by HRS, EHRA, and APHRS in May 2013 and by ACCF, AHA, PACES, and AEPC in June 2013[J]. Heart Rhythm,2013, 10(12):1932-1963.

[3] Basso C, Carturan E, Pilichou K,et al.Sudden cardiac death with normal heart: molecular autopsy[J]. Cardiovasc Pathol,2010, 19(6):321-325.

[4] Fishman GI, Chugh SS, Dimarco JP,et al. Sudden cardiac death prediction and prevention: report from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Heart Rhythm Society Workshop[J]. Circulation, 2010, 122(22):2335-2348.

[5] Doolan A, Langlois N, Semsarian C.Causes of sudden cardiac death in young Australians[J]. Med J Aust,2004, 180(3):110-112.

[6] Willinger M, James LS, Catz C. Defining the sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS): deliberations of an expert panel convened by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development[J]. Pediatr Pathol,1991, 11(5):677-684.

[7] Beckwith JB. Defining the sudden infant death syndrome[J]. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med,2003, 157(3):286-290.

[8] Krous HF, Beckwith JB, Byard RW,et al.Sudden infant death syndrome and unclassified sudden infant deaths: a definitional and diagnostic approach[J]. Pediatrics,2004, 114(1):234-238.

[9] Pilmer CM, Kirsh JA, Hildebrandt D,et al.Sudden cardiac death in children and adolescents between 1 and 19 years of age[J]. Heart Rhythm,2014, 11(2):239-245.

[10] Moon RY, Horne RS, Hauck FR.Sudden infant death syndrome[J]. Lancet,2007, 370(9598):1578-1587.

[11] Fard D, Laer K, Rothamel T,et al.Candidate gene variants of the immune system and sudden infant death syndrome[J]. Int J Legal Med,2016, 130(4):1025-1033.

[12] Kochanek KD, Kirmeyer SE, Martin JA,et al.Annual summary of vital statistics: 2009[J]. Pediatrics,2012, 129(2):338-348.

[13] Rudan I, Chan KY, Zhang JS,et al.Causes of deaths in children younger than 5 years in China in 2008[J]. Lancet,2010, 375(9720):1083-1089.

[14] Fleming PJ, Blair PS, Pease A.Sudden unexpected death in infancy: aetiology, pathophysiology, epidemiology and prevention in 2015[J]. Arch Dis Child,2015, 100(10):984-988.

[15] American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. The changing concept of sudden infant death syndrome: diagnostic coding shifts, controversies regarding the sleeping environment, and new variables to consider in reducing risk[J]. Pediatrics,2005, 116(5):1245-1255.

[16] Getahun D, Demissie K, Lu SE,et al.Sudden infant death syndrome among twin births: United States, 1995-1998[J]. J Perinatol, 2004, 24(9):544-551.

[17] Rand CM, Patwari PP, Carroll MS,et al. Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome and sudden infant death syndrome: disorders of autonomic regulation[J]. Semin Pediatr Neurol, 2013, 20(1):44-55.

[18] Blair PS, Mitchell EA, Heckstall-Smith EM,et al.Head covering-a major modifiable risk factor for sudden infant death syndrome: a systematic review[J]. Arch Dis Child,2008, 93(9):778-783.

[19] Trachtenberg FL, Haas EA, Kinney HC,et al.Risk factor changes for sudden infant death syndrome after initiation of Back-to-Sleep campaign[J]. Pediatrics,2012, 129(4):630-638.

[20] Duncan JR, Garland M, Myers MM,et al. Prenatal nicotine-exposure alters fetal autonomic activity and medullary neurotransmitter receptors: implications for sudden infant death syndrome[J]. J Appl Physiol, 2009, 107(5):1579-1590.

[21] St-Hilaire M, Duvareille C, Avoine O ,et al.Effects of postnatal smoke exposure on laryngeal chemoreflexes in newborn lambs[J]. J Appl Physiol,2010, 109(6):1820-1826.

[22] Cerda J, Bambs C, Vera C. Infant morbidity and mortality attributable to prenatal smoking in Chile[J]. Rev Panam Salud Publica,2017, 41:e106.

[23] Blair PS, Fleming PJ, Bensley D,et al.Smoking and the sudden infant death syndrome: results from 1993-5 case-control study for confidential inquiry into stillbirths and deaths in infancy. Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths Regional Coordinators and Researchers[J]. BMJ,1996, 313(7051):195-198.

[24] McDonnell-Naughton M, McGarvey C, O′Regan M,et al.Maternal smoking and alcohol consumption during pregnancy as risk factors for sudden infant death[J]. Ir Med J,2012, 105(4):105-108.

[25] Ford RP, Schluter PJ, Mitchell EA,et al.Heavy caffeine intake in pregnancy and sudden infant death syndrome. New Zealand Cot Death Study Group[J]. Arch Dis Child,1998, 78(1):9-13.

[26] Alm B, Wennergren G, Norvenius G,et al.Caffeine and alcohol as risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome. Nordic Epidemiological SIDS Study[J]. Arch Dis Child,1999, 81(2):107-111.

[27] Kiechl-Kohlendorfer U, Moon RY.Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and child care centres (CCC) [J]. Acta Paediatr,2008, 97(7):844-845.

[28] Simpson JM. Infant stress and sleep deprivation as an aetiological basis for the sudden infant death syndrome[J]. Early Hum Dev, 2001, 61(1):1-43.

[29] Filiano JJ, Kinney HC.A perspective on neuropathologic findings in victims of the sudden infant death syndrome: the triple-risk model[J]. Biol Neonate,1994, 65(3-4):194-197.

[30] Van Norstrand DW, Ackerman MJ. Genomic risk factors in sudden infant death syndrome[J]. Genome Med,2010, 2(11):86.

[31] Blackwell CC, Moscovis SM, Gordon AE, et al. Cytokine responses and sudden infant death syndrome: genetic, developmental, and environmental risk factors[J]. J Leukoc Biol,2005, 78(6):1242-1254.

[32] Dashash M, Pravica V, Hutchinson IV,et al.Association of sudden infant death syndrome with VEGF and IL-6 gene polymorphisms[J]. Hum Immunol,2006, 67(8):627-633.

[33] Kääb S. Genetics of sudden cardiac death-an epidemiologic perspective[J]. Int J Cardiol, 2017, 237:42-44.

[34] Bagnall RD, Weintraub RG, Ingles J,et al. A Prospective Study of Sudden Cardiac Death among Children and Young Adults[J]. N Engl J Med,2016, 374(25):2441-2452.

[35] Semsarian C, Ingles J, Wilde AA. Sudden cardiac death in the young: the molecular autopsy and a practical approach to surviving relatives[J]. Eur Heart J, 2015, 36(21):1290-1296.

[36] Aro AL, Chugh SS. Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death in Children and Young Adults[J]. Prog Pediatr Cardiol,2017, 45:37-42.

[37] Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ.Sudden infant death syndrome: how significant are the cardiac channelopathies [J].Cardiovasc Res,2005, 67(3):388-396.

[38] Cronk LB,Ye B,Kaku T,et al.Novel mechanism for sudden infant death syndrome:persistent late sodium current secondary to mutations in caveolin-3[J].Heart Rhythm,2007, 4(2):161-166.

[39] Arnestad M, Crotti L, Rognum TO,et al.Prevalence of long-QT syndrome gene variants in sudden infant death syndrome[J]. Circulation,2007, 115(3):361-367.

[40] Ioakeimidis NS, Papamitsou T, Meditskou S,et al. Sudden infant death syndrome due to long QT syndrome: a brief review of the genetic substrate and prevalence[J]. J Biol Res,2017, 24:6.

[41] Tfelt-Hansen J, Winkel BG, Grunnet M,et al.Cardiac channelopathies and sudden infant death syndrome[J]. Cardiology,2011, 119(1):21-33.

[42] Campuzano O, Allegue C, Partemi S,et al. Negative autopsy and sudden cardiac death[J]. Int J Legal Med,2014, 128(4):599-606.

[43] Vacanti G, Maragna R, Priori SG,et al. Genetic causes of sudden cardiac death in children: inherited arrhythmogenic diseases[J]. Curr Opin Pediatr,2017, 29(5):552-559.

[44] Schwartz PJ, Stramba-Badiale M, Crotti L,et al.Prevalence of the congenital long-QT syndrome[J]. Circulation,2009, 120(18):1761-1767.

[45] Zupancic JA, Triedman JK, Alexander M,et al. Cost-effectiveness and implications of newborn screening for prolongation of QT interval for the prevention of sudden infant death syndrome[J]. J Pediatr,2000, 136(4):481-489.

[46] Spazzolini C,Mullally J,Moss AJ,et al.Clinical implications for patients with long QT syndrome who experience a cardiac event during infancy[J].J Am Coll Cardiol,2009, 54(9):832-837.

[47] Yoshinaga M, Kato Y, Nomura Y, et al.The QT intervals in infancy and time for infantile ECG screening for long QT syndrome [J]. J Arrhythm,2011, 27( 3): 193-201.

[48] Page A, Aktas MK, Soyata T,et al. “QT clock” to improve detection of QT prolongation in long QT syndrome patients[J]. Heart Rhythm,2016, 13(1):190-198.

[49] Immanuel SA, Sadrieh A, Baumert M,et al. T-wave morphology can distinguish healthy controls from LQTS patients[J]. Physiol Meas,2016, 37(9):1456-1473.

[50] Pecini R, Cedergreen P, Theilade S,et al. The prevalence and relevance of the Brugada-type electrocardiogram in the Danish general population: data from the Copenhagen City Heart Study[J]. Europace,2010, 12(7):982-986.

[51] Sarquella-Brugada G, Campuzano O, Arbelo E,et al. Brugada syndrome: clinical and genetic findings[J]. Genet Med,2016, 18(1):3-12.

[52] Hu D, Barajas-Martinez H, Medeiros-Domingo A,et al.A novel rare variant in SCN1Bb linked to Brugada syndrome and SIDS by combined modulation of Na(v)1.5 and K(v)4.3 channel currents[J]. Heart Rhythm,2012, 9(5):760-769.

[53] Van Norstrand DW, Valdivia CR, Tester DJ, et al. Molecular and functional characterization of novel glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 like gene (GPD1-L) mutations in sudden infant death syndrome[J].Circulation,2007, 116(20):2253-2259.

[54] Tokioka K, Kusano KF, Morita H,et al.Electrocardiographic parameters and fatal arrhythmic events in patients with Brugada syndrome: combination of depolarization and repolarization abnormalities[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol,2014, 63(20):2131-2138.

[55] de Asmundis C, Mugnai G, Chierchia GB,et al. Long-term follow-up of probands with Brugada syndrome[J]. Am J Cardiol,2017, 119(9):1392-1400.

[56] Calò L,Giustetto C,Martino A,et al. A New Electrocardiographic Marker of Sudden Death in Brugada Syndrome: The S-Wave in Lead I[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol,2016, 67(12):1427-1440.

[57] Jiménez-Jáimez J,Peinado R,Grima EZ,et al. Diagnostic Approach to Unexplained Cardiac Arrest (from the FIVI-Gen Study)[J]. Am J Cardiol,2015, 116(6):894-899.

[58] Refaat MM, Hassanieh S, Scheinman M.Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia[J]. Card Electrophysiol Clin, 2016, 8(1):233-237.

[59] Sumitomo N. Current topics in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia[J]. J Arrhythm, 2016, 32(5):344-351.

[60] Yu TC, Liu AP, Lun KS, et al. Clinical and genetic profile of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in Hong Kong Chinese children[J]. Hong Kong Med J,2016, 22(4):314-319.

[61] Anttonen O, Junttila MJ, Rissanen H,et al.Prevalence and prognostic significance of short QT interval in a middle-aged Finnish population[J]. Circulation,2007, 116(7):714-720.

[62] Iribarren C, Round AD, Peng JA,et al.Short QT in a cohort of 1.7 million persons: prevalence, correlates, and prognosis[J]. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol,2014, 19(5):490-500.

[63] Mazzanti A, Kanthan A, Monteforte N,et al.Novel insight into the natural history of short QT syndrome[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2014, 63(13):1300-1308.

[64] Rezus C, Floria M, Moga VD,et al.Early repolarization syndrome: electrocardiographic signs and clinical implications[J].Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol, 2014, 19(1):15-22.

[65] Talib AK, Sato N, Kawabata N, et al. Repolarization characteristics in early repolarization and brugada syndromes: insight into an overlapping mechanism of lethal arrhythmias[J].J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol,2014, 25(12):1376-1384.

[66] Hasegawa K, Watanabe H, Hisamatsu T, et al. Early repolarization and risk of arrhythmia events in long QT syndrome[J]. Int J Cardiol,2016, 223:540-542.

[67] Brockmeier K, Nazal R, Sreeram N.The electrocardiogram of the neonate and infant[J].J Electrocardiol,2016, 49(6):814-816.