海面上的两万条"鱼"

2017-12-27作者林纯正CJLim

作者:林纯正CJ.Lim

伦敦大学巴特莱特学院建筑与城市学教授

海面上的两万条"鱼"

作者:林纯正CJ.Lim

伦敦大学巴特莱特学院建筑与城市学教授

“横跨大西洋40年后,建筑师/救生员最终到达目的地——漂浮游泳池。然而,游泳池水体特殊的运动形式——对划水动作的反应,即当他们想要游离某处时,得朝着该处游动,而当他们想要游向某处时,得朝反方向游动,使他们几乎未能发现漂浮游泳池”——雷姆•库哈斯《游泳池的故事》(1997年)

‘Arrival of the Floating Pool after 40 years of crossing the Atlantic, the architects/lifeguards reach their destination. But they hardly notice it due to the particular form of locomotion of the pool – its reaction to their own displacement in water – they have to swim toward what they want to get away from and away from where they want to go.’ – Rem Koolhaas, ‘The Story of the Pool’, 1977

在乔纳森•斯威夫特和儒勒•凡尔纳的科幻小说中经常会看到这样的桥段:俄国现代主义建筑师利用移动式游泳池设施逃离苏联压迫,成功逃往雷姆•库哈斯在《癫狂的纽约》(1978年)中描述的美利坚合众国。与之相反,Brodsky和Utkin却选择留在俄国,制定“富有想象力的建筑计划,试图改变俄国毫无生机、模式化的建筑风格,即随处可见粗糙和设计拙劣的建筑,官僚阶层的染指让原本粗糙的建筑更加低劣,再加上劣质的建筑材料……(只有)逃入想象中的王国才能摆脱病态社会和物质现实,才能治愈社会和物质现实中的弊病”1。1984年,Brodsky和Utkin在 “建筑+都市主义”概念设计竞赛中展示了作品“漫步的海龟”,由一大堆看似自由搭配的部件拼接而成,作品底部是多个大小不一的车轮,方便“海龟”在街头走动。走近观察,“海龟”内部是一个大型“城市迷宫”,由风格迥异、手工建造的智能楼宇组成,仿佛从天而降至原本平淡无奇的城市环境之中,被设计师用于隐喻“特洛伊木马”。

选择迁居他国或坚守故土都是人的基本权利,同样也可以用作应对气候变化时的适应性策略。未来数年,大规模的人口迁移现象预期将会加剧,这通常是复杂的经济、社会和政治因素综合作用的结果,但愈发难以预测的环境状况会加剧人口迁移。气候移民的迁徙模式多种多样:洪水、海啸或地震等无法预知的重大灾害可能导致人类被迫迁离,而干旱等长期持续性影响可能导致渐进式迁移过程。2根据《2006年斯特恩全球气候变化经济评估报告》推测,到2050年因气候变化而导致永久迁移的人数将达到约2亿人。3

In the tradition of the science fi ction (SF) tropes of Jonathan Swift and Jules Verne, the Russian modernist architects used a portable pool infrastructure to escape Soviet oppression to the United States of America in Koolhaas’ ‘Delirious New York’ (1978). Meanwhile, Brodsky and Utkinopted instead to remain in Russia to produce ‘visionary schemes in response to a bleak professional scene in which only artless and ill-conceived buildings, diluted through numerous bureaucratic strata and constructed out of poor materials… [it was] an escape into the realm of the imagination that ended as a visual commentary on what was wrong with social and physical reality and how its ills might be remedied’.1Their ‘Wandering Turtle’ for the 1984 ‘Architecture+ Urbanism’ ideas competition shows a large pile of seemingly ad-hoc elements being pushed through the streets; there are numerous wheels of different sizes that provide mobility. On closer inspection, the ‘Turtle’ is ‘a maze of a big city’ comprised of a diverse collection of crafted and intelligent buildings, presumably being smuggled into the banal urban context, making metaphoric reference to the ‘Trojan Horse’.

Both the decisions to migrate or to remain on-site are basic human rights, and can be applied as adaptation strategies in the face of climate change. Over the coming years, large-scale human displacements are expected to intensify – often the amalgamation of complex economic, social and political drivers, which are exacerbated by increasingly unpredictable environmental conditions.The movement patterns of climate migrants vary: forced migration might result from an unforeseen catastrophe such as floods, tsunami or earthquake, while slow persistent effects of drought on agriculture could cause a gradual migration process.2According to the 2006 Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change, around 200 million people will be permanently displaced as a result of climate change by 2050.3

“为了在极端气候环境下生存,人类需要找到合适的庇护场所,搭建一个便携式临时庇护所是谋求生存过程中的一项重要的人为因素”, Robert Kronenburg如是认为。4供生存使用的建筑物必须具备适应环境、便于单人或团体携带和可就地取材的性能。在《可移动建筑》一书中,Kronenburg记录了可移动建筑的历史,并确认“诺亚方舟”是首个有史可考的可迁移基础设施。5

近代,同类型的设施当属避税天堂——“自由之舰”,这是一座可容纳50 000人生活、工作、度假和享受退休生活的漂浮城市。这一移动式基础设施每三年可绕地球航行一圈,除免税商场、银行、酒店、餐厅、娱乐设施、娱乐场、办公室、仓库、轻工制造及组装企业外,还提供住所、图书馆、学校及一流的医院。为确保一流的交通运输条件,“自由之舰”顶层甲板设有机场,可供私人飞机和小型民用飞机起落。“自由之舰”高107米、宽230米、长1 370米,体型是“玛丽皇后号”的4倍以上。6

船上并未设置宽敞和奢华的住所,而是提供方便迁移的移动式房屋、巡回马戏团、印第安人帐篷和蒙古包用于居住。历史上,蒙古牧民每年都会搬迁三至四次。蒙古包便于搭建和拆卸,当季节转变或别处牧草繁盛时,只需少数畜力,便可将整个打包好的帐篷迁离。与人类的陆地和海洋上的迁移不同的是,大型飞艇“兴登堡号”和“梅肯号”遭遇巨大灾难,此后人类甚少进行航空迁移探险活动。然而,近期法国建筑师Giles Ebersolt创造性使用飞艇在热带雨林林冠层创建可供人类生存的居住环境。“Radeau des Cimes” (1989)是一艘漂浮于森林林冠层的充气艇,犹如在水面上航行的船只。充气艇使用轻质材料制成,表面积巨大,以确保稳定性,充气艇提供了此前无法想象的感受热带雨林环境的方式。

迁移并非是面临气候变化时唯一的应对策略;不可否认的事实是,许多无家可归的人员可能会选择留在原居住地,努力适应自然环境的变化。相应地,政府应带领城市设计师和建筑师构想出新的建筑环境去接纳气候变化,利用可适应的、不确定性的灵活体系和移动式基础设施增强整个社会的恢复能力,而非“对抗”气候变化,从而减少流离失所和迁移的人群——气候变化既是机遇,又是挑战。Kronenburg列举出阿基格拉姆学派、Cedric Price、Future Systems和Lebbeus Woods,他们的设计理念已经开始影响建筑和基础设施的设计(通常是在设计方案需要兼顾必要性、创造性思维和透彻理解现实问题时)。7

随着海平面上升,马尔代夫群岛面临被吞没的风险。2008年,马尔代夫总统当选人默罕默德•纳西德提出一项计划,即利用旅游收入设立“主权财富基金”,购置海拔更高的土地,确保30万岛民的后代可在别处重建家园。纳西德向媒体宣称马尔代夫民众不希望“人间天堂沦为气候难民营”。8到2100年,海平面预期将上升10至100厘米,马尔代夫乃至其首都马累都将被海水吞没。马尔代夫全国多地势低洼的群岛,领海面积多于陆地面积,是全世界最平坦和地势最低的国家。

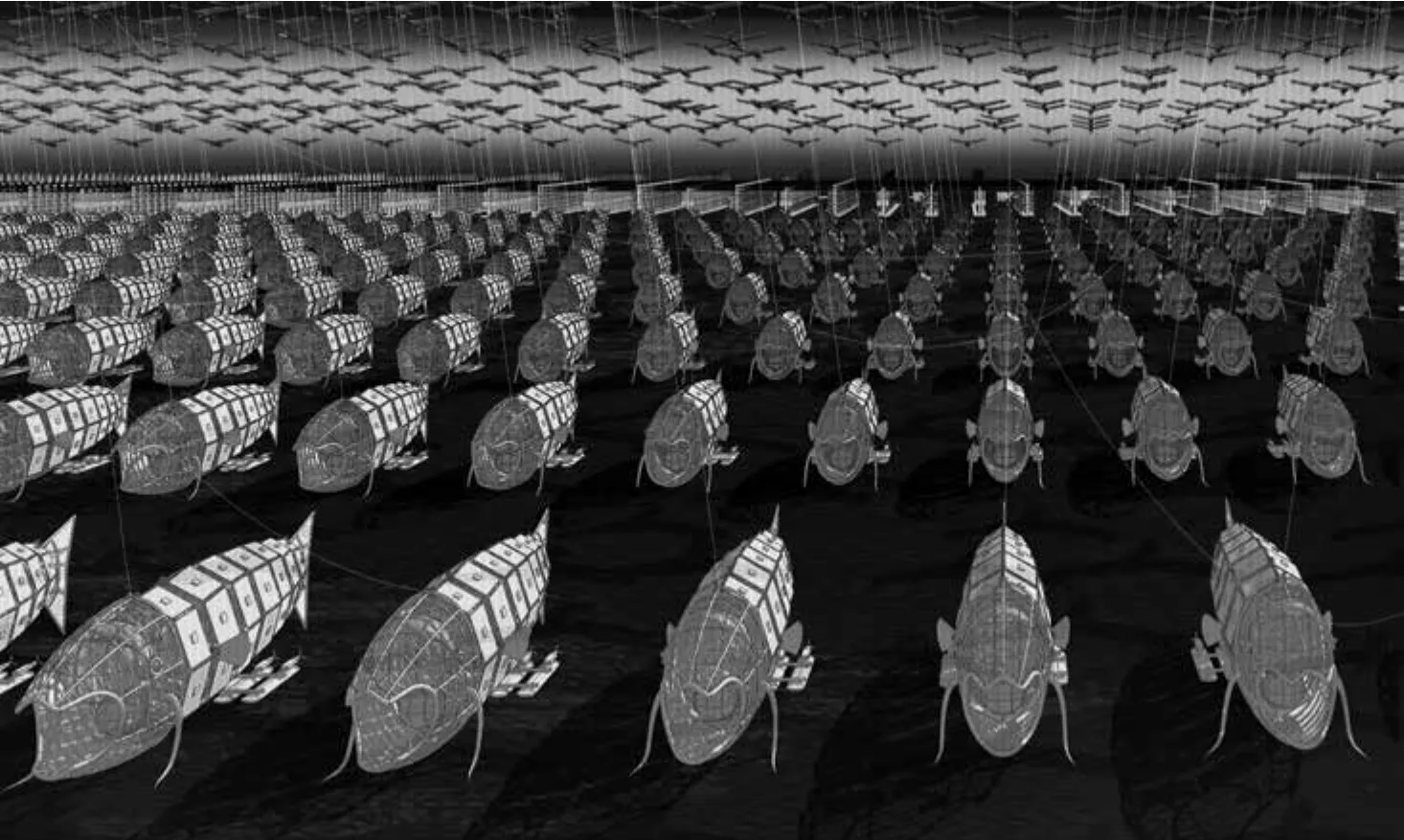

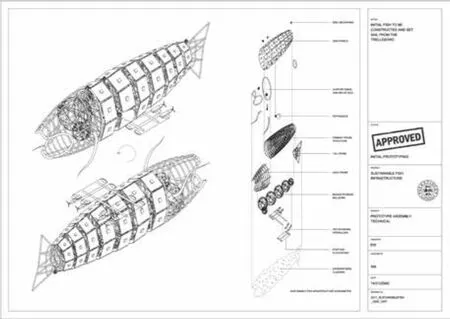

除购置地势更高的土地外,“海面上的两万条鱼”或许是马尔代夫等面临淹没或成为气候移民的岛国的另一条出路。鱼实为浮动式基础设施,具备可移动、轻质和可持续性的特点,主张三条行动原则:保护,供给,鼓励参与环境灾难预测或承担后果。鱼型建筑在彼得库克/阿基格拉姆学派的“速生城市(1971年)”的思辨传说中切实存在,在每个阶段鱼型建筑都基于当时的技术应用。鱼型建筑由多件不同的人工制品和系统组成,有关制品和系统至今仍然作为单独的机械、外壳或实验用具。

对于选择留在原居住地的人而言,外观奇特的鱼型基础设施配备富有创造力的多用途改装配件。鱼型基础设施的主要用途是及时提供有效保护,让人们处于安全的环境中,从而防止出现人员伤亡。每条“大鱼”腹中可供500人躲避,鱼腹中的每间小型预制住房单元均配备弹出式治疗室。整体而言,这一新型人道主义居住点将提供洁净水、卫生设备、食品和卫生保健等生活必需品。当发生灾难时,鱼型主体基础设施会向受灾地区派遣救生船营救流离失所的人员、被困人群、历史文物和当地动植物群。

从抵达那一刻起,鱼型舰队将自动重组——鱼尾翻转为垂直状,用于吸收风能和太阳能,鱼头设有海水淡化和过滤设施。过滤后的饮用水储存在鱼型建筑中空的结构框架内,供日常饮用。提供能源是人道主义援助的重要部分,十分有助于环境的转变。来自海地的国际生命线基金(International Lifeline Fund)的Raffaella Bellanca认为:“人们可以将营地想象成普通的城镇,城镇内的生活按照商品交换和服务的标准经济原则运行。城镇需要能源维系镇民的生活。城镇获得的能源越多,镇民过上丰富生活的可能性就越大,城镇日后重新融入社会的可能性也越大,镇民越不需要依靠他人捐助,也就越有可能有尊严的生活”。9安全获取燃料和能源计划已吸引联合国多个机构、维和部队和非政府组织参与能源问题,关注如何以最优的方式实现“绿色”获取。10

鉴于受影响环境中缺乏干燥或安全的土地,每条鱼都携带可提供结构性自我修复技术的工具。鱼鳞状面板形成新的地基,可移动的漂浮面板铺设在水面上,提供紧急漂浮表面。鱼型建筑可进一步转变为“自建土地”,近似于的的喀喀湖面上漂浮着的“芦苇岛”,当地居民既通过参与土地建设谋生,又有助于以可持续性方式管理自然资源。一部分居民负责种植和收割芦苇,另外一部分居民负责制作手工编织的地面。该项目十分倚赖所有相关人员的参与和合作。

最后,鱼型建筑注重培养难民的才能、技术和理想;建筑内部空间鼓励多功能使用,包括露天平台和漂浮平台上的社区大厅、学校和运动场。鱼鳍状天线充当临近社区通讯网络,同时起到连接鱼型舰队的作用。

无论当地居民选择留下或迁移,在气候变化和可持续发展的背景下,“海面上的两万条鱼”为全球范围内的难民提供了寓言式、可改装的“诺亚方舟”。虽然听起来像科幻小说,但随着海平面上升日渐威胁到全球地势低平国家的生存,鱼型建筑可能会更加常见。一个有效及时的人道主义救援设施可拯救成千上万的生命,想象力是其可适应性和多功能性的唯一限制因素。

‘Humans require shelter in order to survive the extremes of the world’s climate, the ability to create a portable or temporary shelter is one of if not the most important human-made factor in their survival’,argued Professor Robert Kronenburg.4Architecture for survival needs to be adaptable, easily transported by individuals or by a community, and if applicable, utilize indigenous materials. In his book‘Architecture in Motion’, Kronenburg chronicled the history of portable architecture and identified the first recorded infrastructure of migration to be ‘Noah’s Ark’.5

In more recent times, there is of course the tax haven ‘Freedom Ship’ – a floating city for 50,000 people to live, work, vacation and enjoy retirement. The proposed portable infrastructure would continuously circle the globe every three years, with the intention to o ff er residential space, a library, schools, and a first-class hospital in addition to duty-free shopping mall, banks, hotels, restaurants, entertainment facilities, casinos, offices, warehouses, and light manufacturing and assembly enterprises. To ensure first class accessibility, there is the airport on the ship's top deck to serve private and small commercial aircraft. The community on the sea measures 107 meters in height, with a width of 230 meters, and a length of 1,370 meters, more than 4 times longer than the RMS Queen Mary.6

At the opposite end of scale and luxury, mobile homes, the travelling circus, the Native American Tipi and the Mongolian Yurt have provided the necessary facilities and freedom to migrate. Mongolian nomads historically moved three to four times a year. A yurt is easy to set up and take down; and with a few animals, the entire packed dwelling can be transported from one place to another as seasons change or as pastures become greener elsewhere. In contrast to mankind’s migration on land and water, expeditions by air have been rare after the catastrophic disasters that befell the giant airships‘Hindenburg’ and ‘Macon’. Dirigibles, however, have more recently been used to ingenious e ff ect by French architect, Giles Ebersolt, to position living environments on the treetop canopies of tropical rainforests. The ‘Radeaudes Cimes’ (1989) is an in flatable raft that fl oats on the forest canopy like a boat sailing on the waves. Constructed out of lightweight materials with a large surface area to maximise stability, the raft provides previously unimaginable access to the forest environment.

Migration is not the only response strategy to climate change; it is widely agreed that many displaced are likely to remain in their communities and seek to adapt to nature’s impacts. Correspondingly,rather than ‘fighting’ climate change, governments together with planners and architects need to envision built environments that embrace the enemy; strengthening community resilience with flexible systems and portable infrastructures that are able to adapt in uncertainty can reduce displacement and relocation – this is both an opportunity and a challenge. Kronenburg singled-out Archigram, Cedric Price, Future Systems and Lebbeus Woods, who have come to in fl uence the design of architecture and infrastructures ‘usually in situations where necessity, imaginative thinking and a consummate understanding of the issues have been factors in the generation of the solution’.7

In 2008, the then President-elect of the Maldives, Mohammed Nasheed, announced a plan to create a ‘sovereign wealth fund’ using tourism revenues to buy higher land so that the future descendants of the 300,000 islanders will have somewhere to rebuild their lives as sea level rise threatens to drown the archipelago. Nasheed told the media that Maldivians do not want to ‘trade a paradise for a climate refugee camp’.8With future sea levels projected to increase in the range of 10 to 100 centimeters by the year 2100, the entire country of the Maldives, including its capital city Malé, could be submerged.A series of low-lying archipelagos with more territorial sea than land, the islands are the fl attest and lowest country in the world.

As an alternative to buying higher land, ‘Twenty Thousand Fish Above the Sea’ might be the solution for island nations like the Maldives facing the choice of either taking to the water or becoming climate migrants. Portable, lightweight, and sustainable, the Fish is a fl oating infrastructure that advocates three principles of action: to protect, provide and encourage participation in the anticipation or the aftermath of an environmental disaster. The Fish, in the speculative tradition of Peter Cook/Archigram’s‘Instant City’ (1971), is a practical reality since at every stage it is based on existing techniques and their application. There is a combination of several different artifacts and systems, which hitherto remained as separate machines, enclosures or experiments.

For many who chose to remain in their community, the alien infrastructure offers an imaginative multiuse adaptation kit. The primary aim is to prevent human casualties by making available immediate protection in a safe environment – each large Fish is big enough to shelter 500 people, and the smaller modules are equipped with pop-up medical surgeries. Collectively, the new typology of humanitarian outpost provides access to the essentials of clean water, sanitation, food, and health care. Lifeboats,from within the main Fish infrastructure, are dispatched to affected communities, in hope of rescuing dislocated individuals and isolated groups as well as heritage artifacts, and native fauna and flora.

From the moment of arrival, the armada of Fish deconstructs – the tail flips into a vertical position to harvest wind and solar energy, while its head has the facility to desalinate and filter seawater. Filtered potable water is stored in the hollow structural framework of the Fish for everyday consumption.Provision of energy is a crucial part of humanitarian response and can contribute substantially to the transformation of the affected environment. Raffaella Bellanca, of the International Lifeline Fund in Haiti argues that ‘camps can be imagined as ordinary towns that function on the standard economic principles that regulate the exchange of goods and services. These towns need energy to maintain the life they host. The greater the access to energy, the more opportunities there is for a meaningful life, for reintegration into society afterwards, for less dependence on donors and for a chance to live with dignity’.9The Safe Access to Fuel and Energy (SAFE) initiative has secured the participation of many UN agencies, peacekeeping forces and NGOs in energy issues and focus on how best to ‘green’procurement.10

In view of the shortage of dry or safe ground in affected environments, each Fish carries tools to provide the technology of structural self-replication. The fi sh scale-like panels form the foundations of the new ground; the portable and buoyant panels are tiled over water to provide an instant emergency floating surface. The kit has a further adaptation opportunity to ‘make-your-own-land’, akin to the reed-woven floating infrastructures on Lake Titicaca. Local participation in land fabrication can create livelihood opportunities and help manage natural resources in a sustainable manner. Some within the community are responsible for cultivating and harvesting the reed, while others participate in crafting new ingenious woven-ground. The program relies heavily on partnership and collaboration of all stakeholders.

Finally, the Fish recognize the importance to nurture talents, skills, and aspirations of the displaced;spaces within the infrastructure that encourage multi-use participation including community halls,schools and playgrounds on open platforms and floating terraces. Fin-like antennas connect the armada of fi sh whilst servicing communication networks between neighboring communities.

Whether communities opt to remain or migrate, the ‘Twenty Thousand Fish Above the Sea’ offers an allegorical adaptable ‘Noah’s Ark’ to the globally displaced in the context of climate change and sustainability. It may seem like SF, but as rising sea levels threaten low-lying nations around the world, communities like the one in Malé may become more common. An effective and timely humanitarian relief infrastructure has the capacity to save thousands of lives – its adaptability and multi-use is limited only by the imagination.

注释:

1 LE Nesbitt, ‘Brodsky & Utkin: The Complete Works’, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 2003, pp.28-29

2 The Science Communication Unit UWE, ‘Science for Environmental Policy: Migration in response to environmental change’, The European Commission DG Environment, issue.51,September 2015, p.3

3 N Stern, ‘2006 Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change’, HM Treasury, London,2006, p.vi

4 R Kronenburg, ‘Architecture in Motion: The history and development of portable building’,Routledge, New York, 2014, p.7

5 R Kronenburg, ‘Houses in Motion’, Academy Editions, London, 1995, p.21

6 ‘City At Sea’, Freedom Ship International [http://freedomship.com], retrieved 3 August 2016

7 R Kronenburg, ‘Houses in Motion’, Academy Editions, London, 1995, p.133

8 J Vidal, ‘Global Warming Could Create 150 Million Climate Refugees by 2050’, The Guardian: Climate Change, 3 November 2009

9 R Bellance, ‘Sustainable Energy Provision Amongst Displaced Populations: Policy and practice’, The Royal Institute of International A ff airs (Chatham House): Energy, Environment and Resources, December 2014, p.42 [https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/ fi les/chathamhouse/ field/ field_document/20141201Energy Displaced Populations Policy Practice Bellanca.pdf], retrieved 11 June 2016

10 R Bellance, ‘Sustainable Energy Provision Amongst Displaced Populations: Policy and practice’, The Royal Institute of International A ff airs (Chatham House): Energy, Environment and Resources, December 2014, p.2 [https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/ files/chathamhouse/ field/ field_document/20141201Energy Displaced Populations Policy Practice Bellanca.pdf], retrieved 11 June 2016

Twenty Thousand Fish above the Sea

Author: CJ Lim

Professor of Architecture and Urbanism at The Bartlett,UCL Design team: CJ Lim with Eric Wong, Steve Mc Cloy, Jason Lamb

"Inhabitable Infrastructures: Science fiction or urban future?" ,Published by Routledge,2017 ISBN 978-1138119673

设计小组: CJ Lim, Eric Wong, Steve McCloy, Jason Lamb《宜居基础设施:科幻还是未来?》,劳特利奇出版,2017 ISBN 978-1138119673