NPHP3基因突变致婴幼儿期进展为终末期肾病的肾单位肾痨2例并文献复习

2017-12-02李国民刘海梅翟亦晖吴冰冰

李国民 刘海梅 陈 径 孙 利 曹 琦 沈 茜 翟亦晖 吴冰冰 徐 虹

NPHP3基因突变致婴幼儿期进展为终末期肾病的肾单位肾痨2例并文献复习

李国民1)刘海梅1)陈 径1)孙 利1)曹 琦1)沈 茜1)翟亦晖1)吴冰冰2)徐 虹1)

目的 总结2例在婴幼儿期进展为终末期肾病(ESRD)的NPHP3基因突变致肾单位肾痨(NPHP)患儿的临床特征及基因突变的特点。方法 收集患儿的一般情况、肾活检、影像学、实验室检查和基因测序结果,并行文献复习。结果 ①2例均为男性,发病年龄3和17个月,均以黄疸、肝功能异常为首发症状,2例进展至ESRD的年龄分别为11和35个月。例1肾活检病理肾小管间质炎,肾小球轻度病变,未见囊肿;肝脏活检肝细胞弥漫性变性,间质纤维组织增生。未发现家族中有类似疾病。②行高通量测序结果显示,例1存在NPHP3基因 C.2369Agt;G (p.L790P)、c.1358Agt;G (p.L453P)杂合错义突变,例2存在c.1174Cgt;T(p.R392X)无义突变和IVS26-3Agt;G剪切突变。2例均为复合杂合突变,均分别来自患儿父母。p.L453P和p.L790P错义突变及IVS26-3Agt;G剪切突变经软件预测为有害突变。除IVS26-3Agt;G外均为新发现的突变。③共检索到18篇文献1 504例NPHP患者行NPHP3测序,79例检测到NPHP3纯合突变或复合杂合突变。其中19例在新生儿期进展为ESRD,需要肾脏替代治疗,常伴有肺发育不良和胰腺囊肿,在胎儿期表现为羊水少,超声提示双肾增大,伴有囊性改变,常被诊断为常染色体隐性遗传多囊肾;余20例(含文2例)在5岁前进展为ESRD,以肝功能异常和贫血为主要表现,常伴肝脏纤维化和胆管发育异常;42例在5岁后进展为ESRD,以贫血、肾功能异常和高血压等肾脏表型为主。 结论NPHP3基因突变所致NPHP并非传统意义上的青年型NPHP,约半数在5岁前进展为ESRD,故婴幼儿期不明原因的黄疸和肝功能异常应警惕NPHP3基因突变可能。本研究发现的c.1358Agt;G、C.2369Agt;G和c.1174Cgt;T突变为新发现的NPHP3基因突变类型。

婴儿期; 幼儿期; 肾单位肾痨;NPHP3基因

肾单位肾痨(NPHP)是一种罕见的常染色体隐性遗传肾小管间质病,肾脏浓缩功能进行性减退,慢性肾小管间质炎症,通常30岁以内进展为终末期肾病(ESRD),是引起儿童ESRD最常见的遗传性疾病,占儿童ESRD的4%~5%[1-3]。10%~20%的NPHP儿童有肾外症状,称为综合征型NPHP或NPHP相关综合征(NPHP-RS)[4]。至今已发现超过20个基因与NPHP发病相关,NPHP3是最早发现的相关基因之一,早期研究显示NPHP3突变患者进展为ESRD的平均年龄19岁,故称之为青年型NPHP[5]。复旦大学附属儿科医院(我院)近年来收治2例于婴幼儿期进展为ESRD的NPHP3突变患儿,现报告如下。

1 病例资料

例1 男,3岁3个月,因“肝功能异常17个月,肾功能异常11个月”于2014年7月7日至我院就诊。

患儿1岁半时,因“发热伴皮疹”就诊当地医院,诊断“手足口病”,ALT 110 U·L-1,定期随访肝功能;5个月后,因肝功能异常诊断“婴儿肝炎综合征”;10个月后,肝功能未恢复正常,血肌酐(SCr)65 μmol·L-1,肝活检提示肝细胞弥漫性变形、间质纤维组织增生,区域胆管增生,可见炎性细胞浸润。发病以来,一直以复方甘草酸片口服保肝治疗。入我院前2个月“气促、乏力20 d”入当地医院,SCr 497 μmol·L-1,BUN 41.7 mmol·L-1,甲状旁腺素(PTH)287 pg·mL-1,尿蛋白+,血常规Hb 52 g·L-1;骨髓检查显示,增生明显活跃,可见中毒和缺铁改变,巨核细胞减少;肾活检,肾小管间质炎,肾小球轻度系膜增生、节段性内皮细胞增生,诊断慢性肾脏病(CKD)5期,予血液透析、硝苯地平和美托洛尔口服降压等治疗。为进一步诊治至我院。

患儿系G1P1,足月顺产,出生体重3 250 g,无产伤和窒息。父母体健,否认近亲联姻,家族成员无肾脏病病史。

入院查体:血压110/75mmHg,身高95.0 cm,体重14.5 kg。神志清晰,精神可,面色苍白,眼睑和双下肢无水肿。心律齐,无杂音。腹平软,肝肋下3 cm,质软;脾肋下3 cm,质软;双肾区无叩击痛。神经系统查体无异常。

实验室检查:尿沉渣蛋白质+,RBC 0.85个·HP-1,WBC 1.06个·HP-1,尿比重1.010;尿蛋白/肌酐1.86 mg·mg-1;24 h尿蛋白0.16 g;α1微球蛋白(A1MU)/肌酐(CR)447 mg·g-1、白蛋白(ALBU)/CR6 12.4 mg·g-1,球蛋白(IGGU)/CR 59.4 mg·g-1,NAG/CR 1.5 U·mol-1,尿转铁蛋白12.0 mg·L-1。血常规:Hb 64.2 g·L-1,RBC 2.4×1012。ALT 26 U·L-1,AST 24 U·L-1,总蛋白62.4 g·L-1,ALBU 39.1g·L-1,总胆固醇3.36 mmol·L-1,甘油三酯1.88 mmol·L-1,SCr 588 μmol·L-1,BUN 15.8 mmol·L-1。自身抗体阴性。PTH 365 pg·mL-1;电解质、免疫球蛋白、补体均在正常,自身抗体均阴性。 血气分析:pH 7.30、BE -3.1 mmol·L-1。

影像学检查:腹部超声提示,肾脏皮质回声增强,皮髓质分界不清,双肾大小正常;肝质地差,肝门区淋巴结肿大;脾肿大。心脏彩超示,左心室内径增大。

治疗和随访:入院后维持CKD诊断5期、间质性肾炎、肝功能异常。继续血液透析,根据患儿自身条件半月后调整为腹膜透析,并予纠正贫血、降压等,定期门诊随访和入院评估腹膜透析治疗充分性。

例2 男,12月龄,因“肝功能异常9个月,肾功能异常3个月”于2016年1月19日至我院就诊。

患儿3月龄时因“出生后皮肤、巩膜黄染未退”首诊,ALT 184 U·L-1。9月龄时ALT 651 U·L-1、BUN 10.3 mmol·L-1、SCr 102 μmol·L-1,血尿串联质谱及肝病相关基因检测未见明显异常。4 d前因“咳嗽4 d伴发热1 d”就诊,ALT 137 U·L-1、SCr 414.0 μmol·L-1、BUN 30.4 mmol·L-1;血钠132 mmol·L-1、血钾5.3 mmol·L-1、血钙0.76 mmol·L-1,尿常规正常,为进一步诊治至我院。

患儿系G2P1,足月顺产,出生体重3 520 g,无产伤和窒息。父母体健,否认近亲联姻。第1胎孕36周时B超示胎儿双肾增大伴有囊性改变人工流产。家族其他成员无肾脏病病史。

入院查体:血压120/70 mmHg,身长70.5 cm,体重8 kg。神志清晰,精神可,面色苍白,眼睑及双下肢无水肿。两肺未闻及干、湿啰音。心律齐,无杂音。腹平软无压痛,肝肋下3 cm,质软,脾肋下2 cm,质软,双肾区无叩击痛,肠鸣音5次·min-1。神经系统查体阴性。

实验室检查:尿沉渣蛋白质++,RBC 0.31个·HP-1,WBC 0.18个·HP-1;尿比重1.010;尿蛋白/肌酐6.38;A1MU/CR1 061.0 mg·g-1,ALBU/CR 2 602.1 mg·g-1,IGGU/CR 209.1 mg·g-1,NAG/CR 0.94 U·mol-1,尿转铁蛋白12.4 mg·L-1。血常规:Hb 70.0 g·L-1,RBC 2.29×1012;ALT 72 U·L-1,AST 106 U·L-1,总蛋白62.4 g·L-1,ALBU 34.9 g·L-1,总胆固醇9.69 mmol·L-1,甘油三酯7.97 mmol·L-1,肌酐492 μmol·L-1,尿素氮30.7 mmol·L-1,尿酸741 μmol·L-1,血钠121 mmol·L-1,血钾5.4 mmol·L-1,血钙2.54 mmol·L-1,血镁1.10 mmol·L-1,血磷4.26 mmol·L-1,血氯72 mmol·L-1。自身抗体均阴性,甲状旁腺素424 pg·mL-1,免疫球蛋白、补体均正常,血气分析:pH 7.41、BE 5.1 mmol·L-1。

影像学检查:腹部超声提示,肾脏皮质回声增强,皮髓质分界不清,双肾大小正常;肾动态显像(DTPA):双肾灌注差,功能重度受损;肾静态显像(DMSA):右肾小,灌注可,功能受损;MRI:双肾信号异常,复合弥漫性肾损伤;磁共振胰胆管造影(MRCP):肝总管稍扩张;门静脉MRV增强:双肾动脉较细,主动脉发出双肾动脉后主动脉略窄。

治疗和随访:入院后诊断为CKD 5期、间质性肾炎、肝功能异常。入院后予临时血液透析,半月后调整为腹膜透析,予保肝、纠正贫血、降压等,定期门诊随访和入院评估腹膜透析治疗治疗充分性。

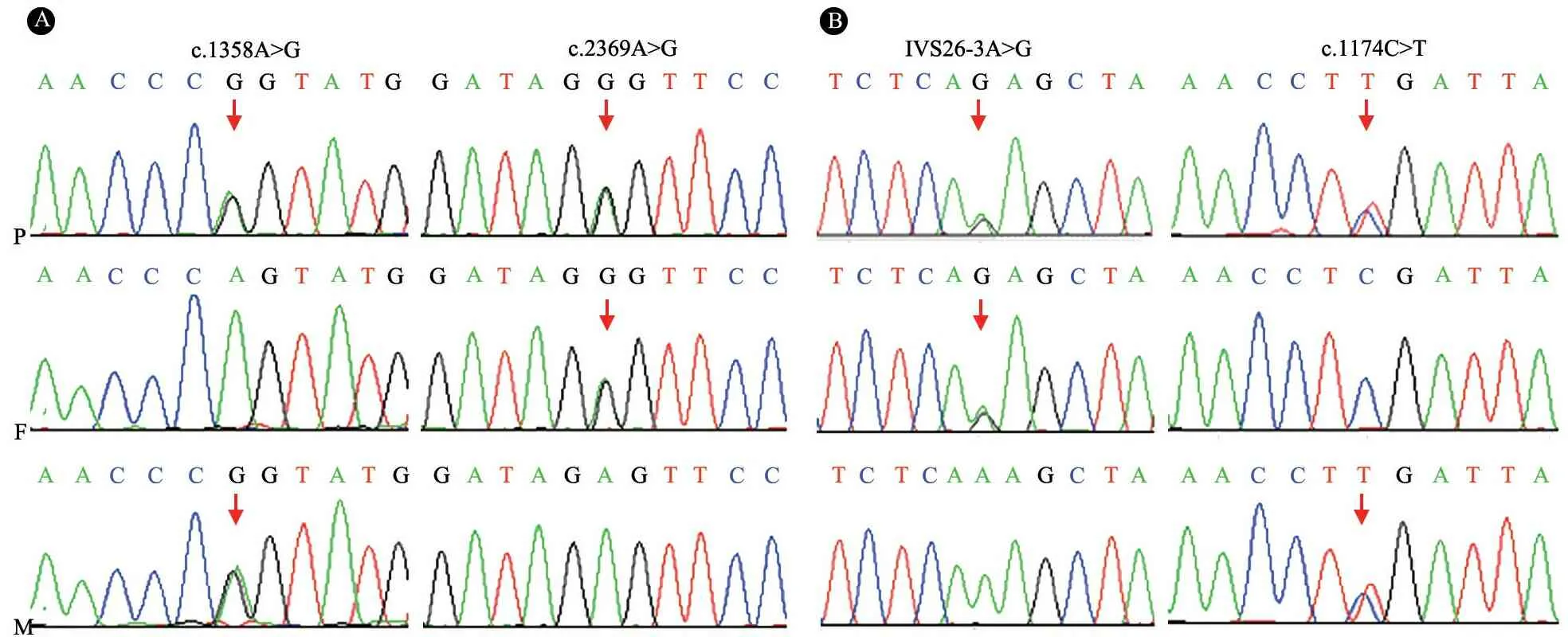

取得患儿父母知情同意后,例1和2分别于入院治疗6个月和3个月时行基因全外显子测序(WES),4 000种单基因高通量测序和Sanger法验证发现,例1存在NPHP3基因 c.1358Agt;G (p.L453P)、C.2369Agt;G (p.L790P)杂合错义突变,家系突变分析发现其母亲携带P.L453P(c.1358Agt;G)突变,父亲携带P.L790P(C.2369Agt;G)突变,患儿为复合杂合突变(图1A)。例2存在c.1174Cgt;T(p.R392X)无义突变和IVS26-3Agt;G剪切突变,家系突变分析发现这两个突变分别来自父母(图1B)。以上突变在100例对照正常人群中均未发现。p.L453P和p.L790P错义突变、IVS26-3Agt;G剪切突变经在线软件PolyPhen和SIFT预测均为有害性突变。以上突变既往未见报道,为新发现的突变。

图1两个家系NPHP3基因验证测序图

注 A:病例1家系,B:病例2家系;P:患者,F:父亲,M:母亲;箭头指示突变位点

2 文献复习

2.1 文献检索策略 以“肾单位肾痨 ANDNPHP3基因”为关键词或主题词在中国知网、万方、维普和中国生物医学文献数据库中检索相关中文文献;以“nephronophthisis ANDNPHP3 gene”为检索式检索PubMed和EBSCO数据库。截止时间为2017年10月20日,纳入符合NPHP诊断并进行了NPHP3测序的文献,排除未进行NPHP3测序的文献以及指南、传统综述和动物实验的文献。

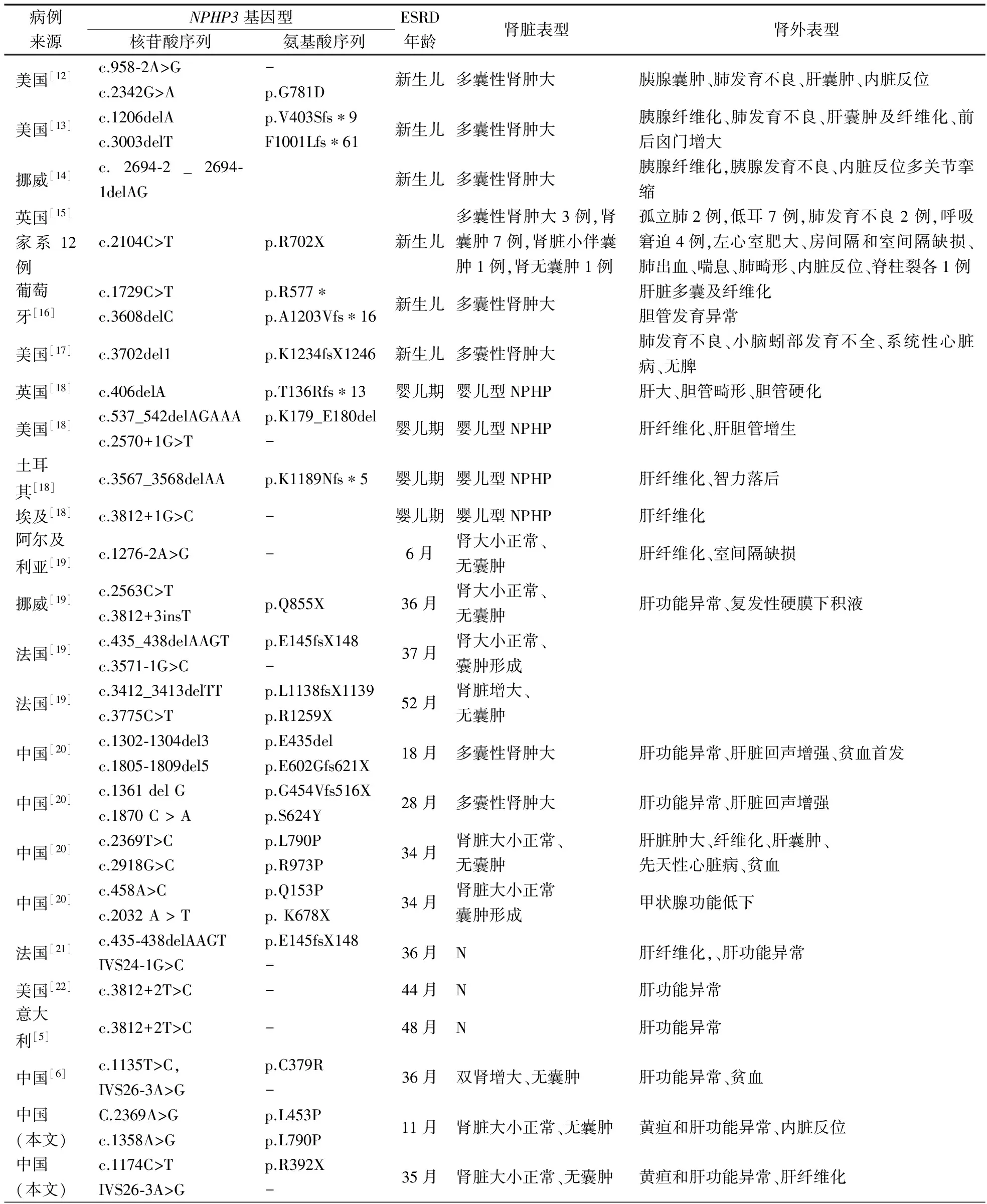

2.2文献检索结果 中文数据库1篇文献符合纳入标准,报道了1例NPHP3突变患者[6]。英文数据库17篇文献符合纳入标准,其中5篇文献共报道了263例NPHP患者测序未发现NPHP3突变或仅有该基因单个杂合突变[7-11];另有12篇文献报道1 242例散发和家族性NPHP患者进行NPHP3测序,共发现79例NPHP3纯合突变或复合杂合突变[ 5,12,22],错义突变7个、终止密码子5个、剪切突变10个、移码突变18个。79例NPHP3基因突变患者中,37例在5岁前进展为ESRD,与本文2例合并后共39例的临床特征见表1。其中19例在新生儿期进展为ESRD,需要肾脏替代治疗,常伴有肺发育不良和胰腺囊肿,这些患儿在胎儿期表现羊水少,超声提示双肾增大伴有囊性改变,常被诊断为常染色体隐性遗传多囊肾。余20例在婴幼儿期进展为ESRD的患儿,以肝功能异常和贫血为主要表现,常伴有肝脏纤维化和胆管发育异常。42例在5岁之后进展为ESRD,以贫血、肾功能异常和和高血压等肾脏表型为主。

表1 39例5岁前进展为ESRD的NPHP3突变患儿基因型与临床表型

注 N:资料不详,-:未受累

3 讨论

加拿大活产婴儿NPHP发病率为1∶50 000[23],芬兰1∶61 800[24],美国1∶1 000 000[25]。我国尚无其发病率报道,至今共报道约20例[26-28]。NPHP的肾脏表现包括多尿、烦渴、继发性遗尿症、贫血、高血压和肾功能异常等。NPHP肾外表现包括:①眼部疾病,包括动眼失用症、眼球震颤和眼组织残缺;②神经系统疾病,包括脑膨出、小脑蚓部发育不全和垂体功能减退症;③肝脏异常,包括肝纤维化等;④骨骼异常,包括短肋、锥形骨骺、多指和和骨骼畸形;⑤其他,包括内脏反位、心脏畸形、支气管扩张症和溃疡性结肠炎等[1, 3, 29]。肾脏病理表现:肾小管间质病变三联征,即肾小管基底膜完整性破坏,表现为不规则增厚或变薄;小管萎缩和髓质囊性变;肾脏间质单个核细胞浸润和纤维化。肾小球病变轻微,早期囊肿可检测不出[3]。目前已发现的与NPHP或NPHP-RS发病相关的致病基因有23个,如NPHP1~19、XPNPEP3、SLC41A1、AHI1和CC2D2A[1-3, 29]。 然而,目前NPHP患者中仍有30%~40%不能通过基因测序明确致病的基因突变[1]。NPHP肾脏B超显示肾脏大小正常或缩小,肾实质回声增强,皮髓质分界不清,髓质可见囊肿[2]。

本文2例NPHP患儿起病年龄小,均有贫血,快速进展为ESRD,伴有肝脏受累; B超提示肾脏皮质回声增强,皮髓质分界不清,其中例1肾活检显示肾小管间质性炎症;2例临床均基本符合NPHP的特征。基因测序发现,例1存在NPHP3 p.L453P和p.L790P错义杂合变异,例2存在NPHP3 p.R392X无义变异和IVS26-3Agt;G剪切变异。2例均为复合杂合突变,分别来自其父母。 p.L453P和p.L790P错义突变以及IVS26-3Agt;G剪切突变经在线软件PolyPhen和SIFT预测均为有害性突变。p.R392X无义变异导致NPHP3编码蛋白提前终止,蛋白截短,影响功能。因此,2例均为NPHP3突变所致发病。除IVS26-3Agt;G外,其余3种突变既往均无报道,为新发现的突变,进一步丰富了NPHP3突变谱。

有研究显示NPHP中,由NPHP3突变所致不到1%[5]。本次文献复习中,共1 507例进行了NPHP3测序的NPHP患者,5.2%(78/1 507)存在NPHP3纯合或复合杂合突变[5,7-22]。国内研究发现,18例NPHP患者中,4/18例(22.2%)患者存在NPHP3复合杂合突变,是目前报道NPHP3突变率最高的地区[19]。截止目前我国共报道7例NPHP3突变所致NPHP患儿,均在5岁之前进展为ESRD。

以往将NPHP3突变所致NPHP称为青年型NPHP[29]。然而,在本次文献复习纳入的全球81例(含本文2例)NPHP3突变患者中,39例在5岁前进展为ESRD[5,6, 12-22]。目前对NPHP患者的基因诊断策略是依据ESRD年龄选择相关基因进行测序分析,如4岁之前进展ESRD患者进行NPHP2基因检测,4岁之后进展ESRD患者进行NPHP1基因检测,检测结果阴性再选择NPHP3等其他基因测序[22];也有文献认为5岁之前进展为ESRD的患者应该分别进行NPHP2、NPHP3和NEK8测序,5岁之后应该行NPHP1基因测序,测序结果阴性再考虑其他基因测序[2]。但由于NPHP涉及的基因较多,且包括NPHP3基因在内多个基因突变的表型有相互重叠,依据进展为ESRD的年龄选择不同致病基因测序的策略很显然不适宜,高通量靶向NPHP基因Panel或WES应该为理想的NPHP基因诊断策略。

进一步分析显示,不同年龄进入ESRD的NPHP3突变患者的临床表型有所差异。新生儿期进入ESRD的患者,一般在胎儿期即有羊水少,双肾多囊性肿大,常累及肝脏、肺、胰腺,引起多器官功能衰竭,被称为肾-肝-胰发育不良(RHPD),常因肺部受累而死亡,有时被误诊为常染色体隐性多囊肾[12-16]。儿童早期(lt;5岁)进入ESRD的NPHP3突变者以肝脏受累为主要表现,如黄疸、肝功能异常,肾脏大小多正常,可以有囊性改变或无囊性改变,基本均有肝纤维化和胆管发育异常等肾外表型[5,6, 18-22]。本研究2例NPHP儿童分别在婴儿期和幼儿期进展为ESRD,均以黄疸和肝功能异常为首发症状,其中例1肝活检提示肝纤维化。肝功能异常的早期儿童在考虑肝脏疾病同时,应该监测尿量、尿比重、Hb、肾功能、肾脏B超,以便及时发现NPHP。而5岁以后进入ESRD的NPHP3突变者以贫血、肾功能异常、高血压等肾脏表型为主[24-28]。

综上所述,NPHP是一类临床和遗传异质性疾病,临床症状隐匿且非特异性,合并肾外症状或以肾外症状起病时容易干扰临床判断。目前已发现超过20个基因与其发病有关,疾病靶向基因或WES有助于遗传分子学诊断,但约1/3的患者致病基因不明确,故仍有必要继续进行家系研究。NPHP3突变者中近半数在5岁前进展为ESRD,故其并非传统意义上的青年型NPHP,婴幼儿期不明原因的黄疸和肝功能异常应警惕NPHP3突变可能。

[1] Wolf MT. Nephronophthisis and related syndromes. Curr Opin Pediatr, 2015, 27(2): 201-211

[2] Simms RJ, Eley L, Sayer JA. Nephronophthisis. Eur J Hum Genet, 2009, 17(4): 406-416

[3] Slaats GG, Lilien MR, Giles RH. Nephronophthisis: should we target cysts or fibrosis? Pediatr Nephrol, 2016, 31(4): 545-554

[4]Wolf MT, Hildebrandt F. Nephronophthisis. Pediatr Nephrol, 2011, 26(2): 181-194

[5] Olbrich H, Fliegauf M, Hoefele J, et al. Mutations in a novel gene, NPHP3, cause adolescent nephronophthisis, tapeto-retinal degeneration and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Genet, 2003, 34(4): 455-459

[6] 张宏文,王芳,姚勇,等. 肾单位肾痨的诊断思路. 中华儿科杂志,2017,55(3):220-222

[7] Otto EA, Ramaswami G, Janssen S, et al. Mutation analysis of 18 nephronophthisis associated ciliopathy disease genes using a DNA pooling and next generation sequencing strategy. J Med Genet, 2011, 48(2): 105-116

[8] Sugimoto K, Miyazawa T, Enya T, et al. Clinical and genetic characteristics of Japanese nephronophthisis patients. Clin Exp Nephrol, 2016, 20(4):637-649

[9] Chen J, Smaoui N, Hammer MB, et al. Molecular analysis of Bardet-Biedl syndrome families: report of 21 novel mutations in 10 genes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2011, 52(8): 5317-5324

[10] Otto E, Hoefele J, Ruf R, et al. A gene mutated in nephronophthisis and retinitis pigmentosa encodes a novel protein, nephroretinin, conserved in evolution. Am J Hum Genet, 2002, 71(5):1161-1167

[11] O'Toole JF, Otto EA, Hoefele J, et al. Mutational analysis in 119 families with nephronophthisis. Pediatr Nephrol, 2007, 22(3): 366-370

[12] Leeman KT, Dobson L, Towne M, et al. NPHP3 mutations are associated with neonatal onset multiorgan polycystic disease in two siblings. J Perinatol, 2014, 34(5): 410-411

[13] Copelovitch L, O'Brien MM, Guttenberg M, et al. Renal-hepatic-pancreatic dysplasia: a sibship with skeletal and central nervous system anomalies and NPHP3 mutation. Am J Med Genet A, 2013, 161A(7): 1743-1749

[14] Fiskerstrand T, Houge G, Sund S, et al. Identification of a gene for renal-hepatic-pancreatic dysplasia by microarray-based homozygosity mapping. J Mol Diagn, 2010,12(1):125-131

[15] Simpson MA, Cross HE, Cross L, et al. Lethal cystic kidney disease in Amish neonates associated with homozygous nonsense mutation of NPHP3. Am J Kidney Dis, 2009, 53(5): 790-795

[16] Penchev V, Boueva A, Kamenarova K, et al. A familial case of severe infantile nephronophthisis explained by oligogenic inheritance. Eur J Med Genet, 2017, 60(6): 321-325

[17] Chaki M, Hoefele , Allen SJ, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation in 440 patients with NPHP-related ciliopathies. Kidney Int, 2011, 80(11): 1239-1245

[18] Halbritter J, Diaz K, Chaki M, et al. High-throughput mutation analysis in patients with a nephronophthisis-associated ciliopathy applying multiplexed barcoded array-based PCR amplification and next-generation sequencing. J Med Genet, 2012, 49(12):756-767

[19] Tory K, Rousset-Rouvière C, Gubler MC, et al. Mutations of NPHP2 and NPHP3 in infantile nephronophthisis. Kidney Int, 2009, 75(8):839-847

[20] Sun L, Tong H, Wang H, et al. High mutation rate of NPHP3 in 18 Chinese infantile nephronophthisis patients. Nephrology (Carlton), 2016, 21(3): 209-216

[21] Hoefele J, Wolf MT, O'Toole JF, et al. Evidence of oligogenic inheritance in nephronophthisis. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2007, 18(10): 2789-2795

[22] Otto EA, Helou J, Allen SJ, et al. Mutation analysis in nephronophthisis using a combined approach of homozygosity mapping, CEL I endonuclease cleavage, and direct sequencing. Hum Mutat, 2008, 29(3): 418-426

[23] Waldherr R, Lennert T, Weber HP, et al. The nephronophthisis complex. A clinicopathologic study in children. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol, 1982, 394(3): 235-254

[24] Ala-Mello S, Koskimies O, Rapola J, et al. Nephronophthisis in Finland: epidemiology and comparison of genetically classified subgroups. Eur J Hum Genet, 1999, 7(2): 205-211

[25] Potter DE, Holliday MA, Piel CF, et al. Treatment of end-stage renal disease in children: a 15-year experience. Kidney Int, 1980, 18(1): 103-109

[26] 管娜,张宏文,丁洁,等. 家族性少年型肾单位肾痨的临床和基因诊断. 临床儿科杂志,2008,26(4): 297-290

[27] 孙良忠,林宏容,岳智慧,等. 少年型肾单位肾痨13例临床特点和基因突变分析.中华儿科杂志,2016,54(11):834-839

[28] Tong H, Yue Z, Sun L, et al. Clinical features and mutation of NPHP5 in two Chinese siblings with Senior-Lo ken syndrome. Nephrology (Carlton). 2013, 18(12): 838-842

[29] Simms RJ, Hynes AM, Eley L, et al. Nephronophthisis: a genetically diverse ciliopathy. Int J Nephrol, 2011, 2011:527137

2017-10-09

2017-10-16)

(本文编辑:张崇凡,孙晋枫)

Progressiontoend-stagerenaldiseaseduringinfancyandearlychildintwochildrenwithjuvenilenephronophthisiscausedbyNPHP3genemutationandliteraturereview

LIGuo-min1),LIUHai-mei1),CHENJing1),SUNLi1),CAOQi1),SHENQian1),ZHAIYi-hui1),WUBing-bing2),XUHong1)

(Children'sHospitalofFudanUniversity,Shanghai201102,China;1)DepartmentofNephrologyandRheumatology, 2)MedicalTranslationalCenter)

Xu Hong, E-mail:hxu@shmu.edu.cn

ObjectiveTo summarize and review the clinical data of two children with juvenile nephronophthisis so as to improve its knowledge.MethodsClinical data of two cases with juvenile nephronophthisis were summarized, including clinical manifestations, laboratory findings, renal pathological changes and imaging data. This study used next generation sequencing to screen 4 000 genes. Significant variants detected by next generation sequencing were confirmed by conventional Sanger sequencing and segregation analysis was performed using parental DNA samples.ResultsTwo cases were both male. The age of onset was 3 months and 17 months respectively. The symptoms of jaundice and liver dysfunction were the first symptoms, 2 cases all progressed to ESRD, at the age of 11 and 35 months respectively. 1 case of renal biopsy showed that renal tubulointerstitial inflammation, mild glomerular mesangial proliferation, segmental endothelial cell proliferation, in line with the renal tubules, the change of small lesion, no cyst; liver biopsy showed liver cell diffuse degeneration, interstitial fibrosis, regional bile duct hyperplasia, inflammatory cells infiltration. Family surveys did not identify members with similar diseases. In case 1, there were heterozygous missense mutations in theNPHP3 gene C.2369Agt;G (p.L790P) and c.1358Agt;G (p.L453P), and in 2 cases there were c.1174Cgt;T (p.R392X) nonsense mutations and IVS26-3Agt;G shear mutations. Family mutation analysis revealed that the above mutations were derived from their parents, and they were complex heterozygous mutations. None of the above mutations was found in 100 normal controls. Both p.L453P and p.L790P missense mutations were predicted to be deleterious mutations by online software PolyPhen and SIFT, and IVS26-3Agt;G shear mutations were also predicted to be deleterious mutations by the online software MaxEntScan. None of the above mutations had previously been reported. High throughput sequencing revealed no mutations causing other diseases. A review of the literature found that a total of 18 articles (Chinese 1 article) met the inclusion criteria, in these reported 1 504 cases of sporadic and familial NPNP patients byNPHP3 gene sequencing,NPHP3 gene were found in 79 cases with homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations. Of these 79 cases of patients withNPHP3 mutation, 19 cases in the neonatal period had progressed to ESRD, and needed renal replacement therapy, were often associated with lung hypoplasia, pancreatic cyst, these patients showed less fetal amniotic fluid, bilateral renal enlargement by ultrasound and cystic change. They were usually diagnosed as autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. 20 cases (including 2 cases of this study) progressed to ESRD before the age of 5, with abnormal liver function, anemia was the main manifestation, often accompanied by liver fibrosis and bile duct dysplasia. The other 42 cases progressed to ESRD after the age of 5 showed anemia, renal dysfunction, hypertension and renal phenotype.ConclusionNPHP caused by mutations inNPHP3 gene is not juvenile nephronophthisis in the traditional sense, becauseNPHP3 patients can progress to end-stage renal disease at any age. If infant and early child present with unknown jaundice and abnormal liver function, which may be caused by mutations inNPHP3 gene. c.1358Agt;G, C.2369Agt;G and c.1174Cgt;T mutations are novel mutations in this study, they may further expand theNPHP3 gene mutation spectrum.

Infancy; Early child; Nephronophthisis;NPHP3 gene

复旦大学附属儿科医院 上海,201102;1)肾脏和风湿科, 2)医学转化中心

徐虹,E-mail: hxu@shmu.edu.cn

10.3969/j.issn.1673-5501.2017.05.009