神经生长因子对单纯疱疹病毒性角膜炎的治疗作用与机制

2017-11-28黎玥徐建江

黎玥 徐建江

·综述·

神经生长因子对单纯疱疹病毒性角膜炎的治疗作用与机制

黎玥 徐建江

单纯疱疹病毒性角膜炎(HSK)是由单纯疱疹病毒所致的角膜炎,是世界范围内致盲的一个重要原因,而其复发性及对阿昔洛韦日渐增加的耐药性让医师在治疗过程中感到棘手,寻求可替代的药物成为未来的趋势。神经生长因子(NGF)现认为不仅存在于神经系统中,也存在于多种组织中,并且作为一种免疫调节因子发挥作用。NGF及其受体也存在于角膜上。近年有学者在动物模型以及临床上将其用于HSK的治疗,取得了很好的效果。本文将NGF对HSK的作用,以及其影响角膜损伤修复、角膜神经再生、Toll样受体通路及维持病毒潜伏状态等相关机制进行综述,为后续研究方向提供参考。(中国眼耳鼻喉科杂志,2017,17:436-440)

神经生长因子;单纯疱疹病毒性角膜炎;角膜损伤修复;角膜神经再生;Toll样受体;病毒潜伏

单纯疱疹病毒(herpes simplex virus,HSV)是一种高度流行的病原体,特别是HSV-1,据估计全世界60%~80%的人群都感染了该病毒[1],而单纯疱疹病毒性角膜炎(herpes simplex virus keratitis,HSK)是由HSV所引起的角膜感染,绝大多数为HSV-1。因HSV的潜伏后再活化所致慢性病程而导致永久性角膜瘢痕、视力损伤甚至致盲,被认为是世界范围内致盲的一个主要原因[2]。据保守估计,全球HSK的发病数粗算可达每年150万,其中包括4万可致严重的单眼视力损害或盲[3]。据2014年在我国的多中心研究[4]显示,患有HSK的比例达0.11%。HSK无论何种类型,几乎都会用抗病毒药物,其中阿昔洛韦的应用最为广泛,引发了人们对其病毒耐药性的关注。近年已有人从疱疹性角膜炎的免疫正常患者中分离到高达6.4%的对阿昔洛韦耐药的HSV-1[5]。还有值得注意的是,现今的治疗方法并不能完全治愈该病,而只是减轻症状并且帮助维持病毒的潜伏状态。即使使用抗病毒药物,HSK也可复发[6]。因此,无论是HSV再激活所致HSK的易复发性还是HSV可能对抗病毒药产生的耐药性,都提示需要去探索HSK的发病机制并且寻求可替代的治疗药物或方法。

神经营养因子(neurotrophic factors,NT)是一类具有促进神经元存活、生长和抗凋亡作用的蛋白质,其中神经生长因子(nerve growth factor,NGF)作为最早且研究最为广泛的神经营养因子,有两大受体:一是与其他NT成员共享的低亲和力受体p75NTR;二是特异性的高亲和力酪氨酸受体trkA[7]。NGF现认为不仅存在于神经系统中,也广泛存在于其他组织中,如血管、膀胱、平滑肌、视网膜及角膜等;还作为一种免疫调节因子发挥作用,如肥大细胞、巨噬细胞、T细胞及B细胞在免疫过程中都可产生NGF[8]。NGF及其受体也存在于角膜上,关于NGF与角膜疾病的研究也层出不穷。基于HSV的嗜神经性及NGF应用于HSK治疗的有效性,本综述将聚焦于NGF应用于HSK的作用,以及其作用的机制。

1 NGF对HSK的作用

HSK现分为4种主要类型:感染性上皮型角膜炎、神经营养性角膜病变、基质型角膜炎、内皮型角膜炎[9]。绝大多数HSK都是上皮型,以树枝状或地图样溃疡为特点;基质型可由上皮型发展而来,发病率随着复发而提高,而长期复发的角膜炎往往会有神经营养性的因素参与其中;内皮型则少见,且动物模型基本不会涉及内皮型的造模,故本文中提及的HSK是除内皮型外的HSK。

有研究[10]发现,若在HSV感染的兔子模型中系统性应用抗NGF抗体,会诱导HSK的再复发。另有研究证实在兔子中局部应用NGF相较对照组,HSK的程度在临床上及实验室参数上(包括裂隙灯下评分、用免疫学和分子学方法评估病毒复制情况等)都有明显的减轻,其效果与阿昔洛韦组差异没有统计学意义;反之,局部使用抗NGF抗体则会诱导更严重的角膜炎,并且10例中有2例发生了致死的HSV脑炎[11]。甚至有学者在临床上对阿昔洛韦局部和系统应用抵抗的HSK所致角膜溃疡某患者,连续使用23 d NGF滴眼液治疗可致完全的角膜愈合[12]。更有许多研究[13-15]证实了NGF有帮助神经营养性溃疡愈合的作用。从上述研究看,即可发现NGF在病毒性溃疡和神经营养性溃疡的修复、减少病毒复制和扩散以及防止HSK再复发等方面都有有益的作用,虽说在人身上的证据还远远不足,但这些结果都预示着NGF有着很大潜力成为治疗HSK的新选择。

2 NGF与其受体在角膜上的表达

前面已介绍NGF有2种受体,总的来说,大多数NGF介导的生物学活性(从分化/激活到增生/存活)都是依赖于trkA受体通路介导的,后续激活MAPK-Ras-Erk通路、磷脂酶Cy1、P3I激酶和短核转导蛋白等[16]。p75NTR独立诱导特殊的转导途径,该途径包括NF-κB和c-Jun激酶,并产生更多的神经酰胺,这些因子可介导基因的转录或程序性细胞死亡[17]。以下研究证实了NGF及其受体在角膜上的表达。

Lambiase等[18-19]发现在正常生理状态下,人和大鼠的角膜产生并储存NGF,主要由上皮、角膜细胞和内皮产生;在体外培养的人和大鼠角膜上皮细胞也可产生储存和分泌NGF,同样也表达trkA。因此,作者认为在同一细胞上NGF及其受体的同时表达,提示角膜上皮细胞很有可能是通过自分泌或旁分泌机制来维持其存活并发挥作用。Qi等[20]用免疫荧光染色的方法发现NGF的免疫活性仅位于人类角膜缘基底上皮细胞小部分,而在整个角膜和角膜缘高于基底细胞的上皮层都未检测到活性;trkA受体的分布与Lambiase等的研究结果相同,即主要局限在基底上皮细胞,角膜及角膜缘的基质层都未检测到活性;而对于p75NTR,免疫荧光染色使得角膜和角膜缘基底层和紧邻着的上皮层显色,再上层的上皮层不显色,在角膜缘区域的基质细胞包括血管内皮细胞、神经纤维和成纤维细胞都为强显色。由此可以看出,NGF对HSK产生相应的作用并非偶然,而是有相应的结构及分子学基础。

3 现有的机制进展

现有如下的相关研究,可能是NGF对HSK产生作用的基础。

3.1 NGF促进角膜损伤的修复 在HSV感染的初始,多以点状的上皮病变为表现,故大多数的HSK都伴有上皮的损害,而较深的角膜溃疡和基质型角膜炎都可以累及角膜基质。角膜损伤的修复是一系列十分复杂的连锁反应,涉及上皮细胞、基质角膜细胞、角膜神经、泪腺、泪膜和免疫细胞之间的细胞因子调节[21]。

NGF可以从多个方面参与修复过程。首先,在体外培养的人类角膜上皮中,NGF可以促进角膜上皮细胞的增殖和分化,且这种作用可能是通过Art和Erk信号通路促进细胞周期蛋白D的激活,从而影响到人类角膜上皮的细胞周期进程(从G1期转为S期)来实现的[22-23]。其次,角膜细胞可转化为特殊的成纤维细胞样角膜细胞及成肌纤维细胞参与愈合过程[21]。有研究在体外培养的成纤维细胞样角膜细胞上发现了NGF,trkA-NGFR和p75NTR的表达,NGF的加入可以促进这些细胞分化为成肌纤维细胞、促进迁移,还可促使金属蛋白酶-9(MMP-9)的表达和活性及3D胶原晶格结构的收缩[24]。在成年母鸡的体内实验中发现,NGF的处理促进了角膜上皮迁移,从而帮助了更快的愈合,且这个效应是通过MMP-9的上调和β4整合素的裂解实现的[25]。最终,愈合过程的终止是需要成肌纤维细胞的缺失,在体外NGF可能作为成肌纤维细胞凋亡的诱导因子,且此过程是通过p75NTR介导的,当trkA/p75比例中p75占主导时则会倾向于该过程[26]。所以,NGF可以帮助角膜上皮细胞的增殖、分化、迁移,并进一步调节成肌纤维细胞来促使角膜损伤的修复。

3.2 角膜神经纤维再生 正常的角膜神经分布对维持正常的角膜结构和功能十分重要,而疱疹性角膜炎是最为常见的致使角膜感觉损伤的原因。研究发现,HSK眼中角膜感觉损伤与基底膜下神经丛的明显减少密切相关,随着HSK的复发,除了内皮型角膜炎,角膜上皮下的神经丛形态也会逐渐破坏,且这些神经分布的变化是与角膜浅表上皮细胞密度和大小的变化密切相关的[27-29]。而神经纤维的再生在神经营养性角膜炎中的作用更不用多说。

NGF在神经纤维再生方面起到了作用。早在20世纪,NGF在体外刺激轴突生长的作用即被证实[30]。TrkA受体缺乏的敲除基因小鼠的角膜神经密度和角膜感觉都是下降的,提示角膜神经分布的形成是NGF依赖性的[31]。在实验性眼科手术致使角膜神经损伤的动物模型中,局部或系统性应用NGF可帮助修复基底膜下的神经丛,且术后早期NGF蛋白和mRNA的变化是与角膜神经丛的密度相关[32-34]。而在辣椒素诱导的大鼠角膜神经损伤模型中,NGF局部滴眼可以改善角膜神经损伤后的一系列变化,如角膜愈合速度、神经分布和泪液分泌等[35]。由此可以看出,NGF对角膜神经的修复作用已在动物模型上多次得到证实,但在人体中使用效果的证据尚不足。

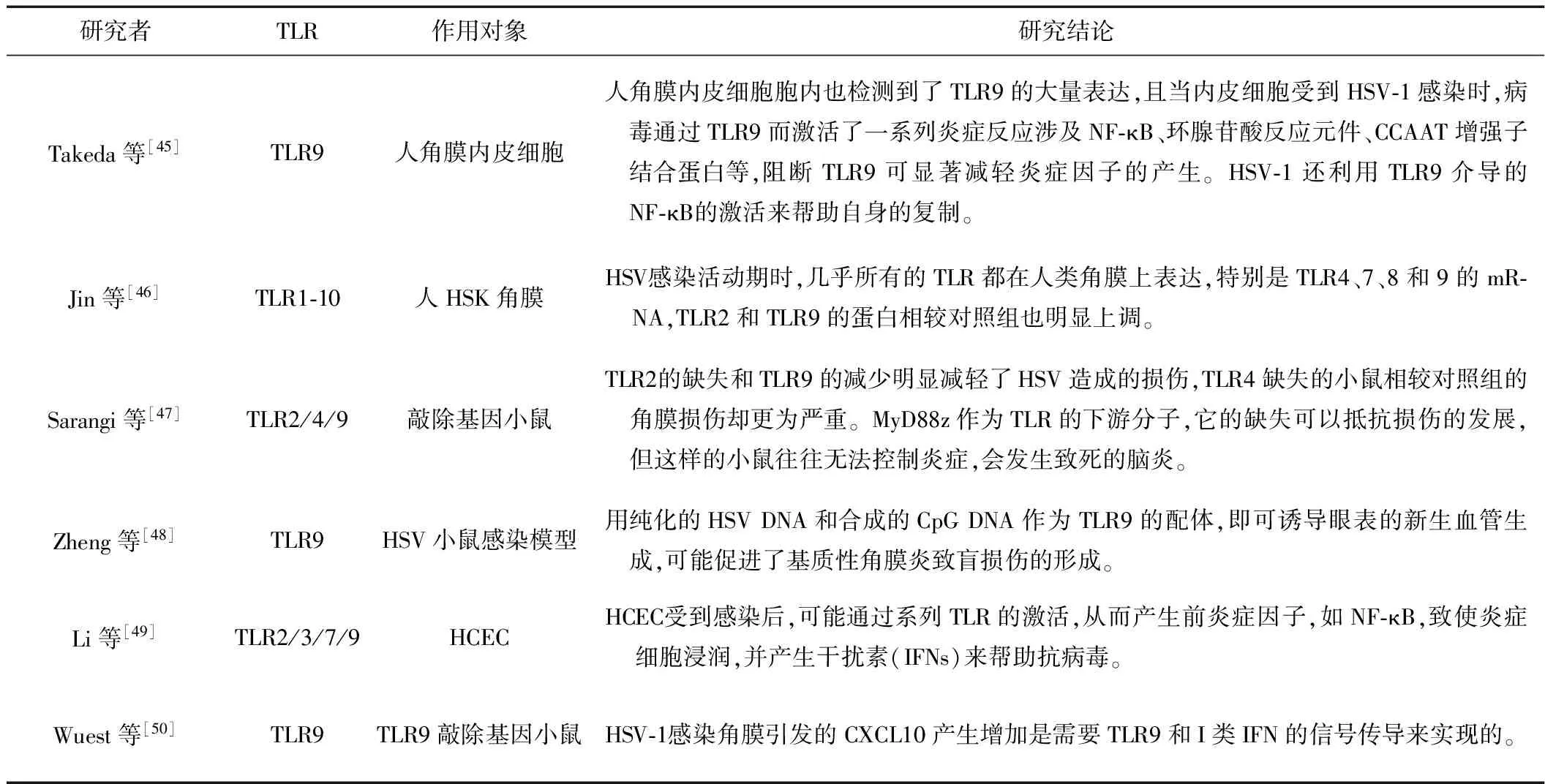

3.3 NGF参与调节TLR通路 HSV在致病过程中,先激活一系列固有免疫反应。其中,Toll样受体(toll-like receptors,TLR)作为重要的一类模式识别受体(pattern recognition receptor, PRR)在感染过程中发挥作用。TLR2可识别HSV-1糖蛋白gB和gH/gL[36-37],TLR3可识别HSV-1 dsRNA[38],TLR9可识别包括HSV-1在内的病毒基因CpG岛[39]。TLR在HSK中的作用具体见表1。一方面,TLR识别HSV-1诱导了免疫防御意在从角膜上清除病毒;另一方面,由于激活了固有免疫,TLR也可能加重免疫反应从而导致角膜破坏[40]。故TLR是HSV感染角膜中重要的一环,而NGF是否对TLR信号通路产生影响从而调节角膜的免疫呢?

在单核细胞中,当炎症刺激物活化TLR产生促炎症反应时,NGF的trkA受体上调,NGF通过激活trkA信号通路,影响TLR通路而下调炎症因子的产生和诱导抗炎因子的生成,从而减轻炎症反应[41]。也有研究者[42]直接用NGF刺激单核细胞,发现了NGF通过trkA受体激活NF-κB进一步调节炎症因子。在树密细胞(DC)中,刺激TLR4信号可以通过p38 MAPK和NF-κB通路的激活增加NGF及其受体p75NTR的表达[43]。VKC起源的结膜上皮细胞中TLR4的表达相对上升而TLR9的表达相对下降,使用NGF后可诱导强烈的TLR4和适当的TLR9表达上调,并可以检测到IL-10的显著下降,不伴有IFN-γ、IL-4和IL-12 p40的明显变化[44]。NGF可能帮助调节TLR相关的炎症反应,但现未有研究在角膜上直接证实,故此不失为未来研究的一个重要方向。

表1 HSK与TLR之间的研究

注:HCEC为人角膜上皮细胞

3.4 NGF与HSV潜伏状态 HSV的嗜神经性使其可潜伏于周围神经中,当某些条件下如紫外线照射、压力、发热、低温、焦虑等[51-53],HSV可再激活从而诱导HSK的复发。这也是对于HSK的治疗让人感到棘手的原因之一。

前面已提到在动物模型中应用抗NGF抗体可以诱导HSK的再复发[10],而在体外NGF的撤退可以诱导感觉和交感神经元中HSV-1的再激活也早就被证实[54],故添加NGF常作为保持HSV潜伏状态的方法之一,但具体的机制的确鲜有人研究。在体外不成熟的神经元中,NGF撤退通常可诱导凋亡信号通路[55],而caspase-3作为p75NGF受体下游重要的因子,它的抑制物可减少HSV-1的再激活,直接激活caspase-3可促进HSV-1的再激活[56]。Camarena等[57]发现在神经细胞中,NGF通过激活trkA受体来持续性激活PI3-K通路对于维持HSV-1潜伏状态十分关键,该通路被打断后,即使是短暂性的,也可引起病毒的再激活。期待有更多的研究阐述其中的机制,这必将对复发性HSK的机制和相关治疗有所帮助。

4 结语

综上所述,NGF对HSK的愈合、减少病毒的复制和扩散及防止其复发具有有益作用,NGF及其受体在角膜上的表达为其提供结构基础,相关的机制可能涉及促进角膜损伤修复、帮助角膜神经再生、影响HSV通过TLR介导角膜炎症及维持病毒潜伏状态等几个方面,但至今为止相关的研究较少,故需要大量的研究进一步探讨NGF与HSK的联系,有望对临床治疗给出新的提示。

[1] Roizman B. Herpes simplex viruses. Fields Virology. 5th ed[M]. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2007.

[2] Kaye S, Choudhary A. Herpes simplex keratitis[J]. Prog Retin Eye Res, 2006,25(4):355-380.

[3] Farooq AV, Shukla D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update[J]. Surv Ophthalmol, 2012,57(5):448-462.

[4] Song X, Xie L, Tan X, et al. A multi-center, cross-sectional study on the burden of infectious keratitis in China[J]. PLoS One, 2014,9(12):e113843.

[5] Duan R, de Vries RD, Osterhaus AD, et al. Acyclovir-resistant corneal HSV-1 isolates from patients with herpetic keratitis[J]. J Infect Dis, 2008,198(5):659-663.

[6] Azher TN, Yin XT, Tajfirouz D, et al. Herpes simplex keratitis: challenges in diagnosis and clinical management[J]. Clin Ophthalmol, 2017,11:185-191.

[7] Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Trk receptors: roles in neuronal signal transduction[J]. Annu Rev Biochem, 2003,72:609-642.

[8] Chang E, Im YS, Kay EP, et al. The role of nerve growth factor in hyperosmolar stress induced apoptosis[J]. J Cell Physiol, 2008,216(1):69-77.

[9] Holland EJ, Schwartz GS. Classification of herpes simplex virus keratitis[J]. Cornea, 1999,18(2):144-154.

[10] Hill JM, Garza HH, Helmy MF, et al. Nerve growth factor antibody stimulates reactivation of ocular herpes simplex virus type 1 in latently infected rabbits[J]. J Neurovirol, 1997,3(3):206-211.

[11] Lambiase A, Coassin M, Costa N, et al. Topical treatment with nerve growth factor in an animal model of herpetic keratitis[J]. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2008,246(1):121-127.

[12] Mauro C, Pietro L, Emilio CC. The use of nerve growth factor in herpetic keratitis: a case report[J]. J Med Case Rep, 2007,1:124.

[13] Lambiase A, Rama P, Bonini S, et al. Topical treatment with nerve growth factor for corneal neurotrophic ulcers[J]. N Engl J Med, 1998,338(17):1174-1180.

[14] Bonini S, Lambiase A, Rama P, et al. Topical treatment with nerve growth factor for neurotrophic keratitis[J]. Ophthalmology, 2000,107(7):1347-1351, 1351-1352.

[15] Tan MH, Bryars J, Moore J. Use of nerve growth factor to treat congenital neurotrophic corneal ulceration[J]. Cornea, 2006,25(3):352-355.

[16] Sofroniew MV, Howe CL, Mobley WC. Nerve growth factor signaling, neuroprotection, and neural repair[J]. Annu Rev Neurosci, 2001,24:1217-1281.

[17] Frade J M, Rodriguez-Tebar A, Barde Y A. Induction of cell death by endogenous nerve growth factor through its p75 receptor[J]. Nature, 1996,383(6596):166-168.

[18] Lambiase A, Manni L, Bonini S, et al. Nerve growth factor promotes corneal healing: structural, biochemical, and molecular analyses of rat and human corneas[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2000,41(5):1063-1069.

[19] Lambiase A, Bonini S, Micera A, et al. Expression of nerve growth factor receptors on the ocular surface in healthy subjects acid during manifestation of inflammatory diseases[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 1998,39(7):1272-1275.

[20] Qi H, Chuang EY, Yoon K, et al. Patterned expression of neurotrophic factors and receptors in human limbal and corneal regions[J]. Mol Vis, 2007,13:1934-1941.

[21] Wilson SE, Mohan RR, Mohan RR, et al. The corneal wound healing response: cytokine-mediated interaction of the epithelium, stroma, and inflammatory cells[J]. Prog Retin Eye Res, 2001,20(5):625-637.

[22] You LT, Kruse FE, Volcker HE. Neurotrophic factors in the human cornea[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2000,41(3):692-702.

[23] Hong J, Qian T, Le Q, et al. NGF promotes cell cycle progression by regulating D-type cyclins via PI3K/Akt and MAPK/Erk activation in human corneal epithelial cells[J]. Mol Vis, 2012,18:758-764.

[24] Micera A, Lambiase A, Puxeddu I, et al. Nerve growth factor effect on human primary fibroblastic-keratocytes: possible mechanism during corneal healing[J]. Exp Eye Res, 2006,83(4):747-757.

[25] Blanco-Mezquita T, Martinez-Garcia C, Proenca R, et al. Nerve growth factor promotes corneal epithelial migration by enhancing expression of matrix metalloprotease-9[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2013,54(6):3880-3890.

[26] Micera A, Puxeddu I, Balzamino BO, et al. Chronic nerve growth factor exposure increases apoptosis in a model of in vitro induced conjunctival myofibroblasts[J]. PLoS One, 2012,7(10):e47316.

[27] Nagasato D, Araki-Sasaki K, Kojima T, et al. Morphological changes of corneal subepithelial nerve plexus in different types of herpetic keratitis[J]. Jpn J Ophthalmol, 2011,55(5):444-450.

[28] Hamrah P, Sahin A, Dastjerdi MH, et al. Cellular changes of the corneal epithelium and stroma in herpes simplex keratitis: an in vivo confocal microscopy study[J]. Ophthalmology, 2012,119(9):1791-1797.

[29] Hamrah P, Cruzat A, Dastjerdi MH, et al. Corneal sensation and subbasal nerve alterations in patients with herpes simplex keratitis: an in vivo confocal microscopy study[J]. Ophthalmology, 2010,117(10):1930-1936.

[30] Recio-Pinto E, Rechler MM, Ishii DN. Effects of insulin, insulin-like growth factor-II, and nerve growth factor on neurite formation and survival in cultured sympathetic and sensory neurons[J]. J Neurosci, 1986,6(5):1211-1219.

[31] de Castro F, Silos-Santiago I, Lopez D AM, et al. Corneal innervation and sensitivity to noxious stimuli in trkA knockout mice[J]. Eur J Neurosci, 1998,10(1):146-152.

[32] Ma K, Yan N, Huang Y, et al. Effects of nerve growth factor on nerve regeneration after corneal nerve damage[J]. Int J Clin Exp Med, 2014,7(11):4584-4589.

[33] Joo MJ, Yuhan KR, Hyon JY, et al. The effect of nerve growth factor on corneal sensitivity after laser in situ keratomileusis[J]. Arch Ophthalmol, 2004,122(9):1338-1341.

[34] Chen L, Wei RH, Tan DT, et al. Nerve growth factor expression and nerve regeneration in monkey corneas after LASIK[J]. J Refract Surg, 2014,30(2):134-139.

[35] Lambiase A, Aloe L, Mantelli F, et al. Capsaicin-induced corneal sensory denervation and healing impairment are reversed by NGF treatment[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2012,53(13):8280-8287.

[36] Cai M, Li M, Wang K, et al. The herpes simplex virus 1-encoded envelope glycoprotein B activates NF-kappaB through the Toll-like receptor 2 and MyD88/TRAF6-dependent signaling pathway[J]. PLoS One, 2013,8(1):e54586.

[37] Leoni V, Gianni T, Salvioli S, et al. Herpes simplex virus glycoproteins gH/gL and gB bind Toll-like receptor 2, and soluble gH/gL is sufficient to activate NF-kappaB[J]. J Virol, 2012,86(12):6555-6562.

[38] Lim HK, Seppanen M, Hautala T, et al. TLR3 deficiency in herpes simplex encephalitis: high allelic heterogeneity and recurrence risk[J]. Neurology, 2014,83(21):1888-1897.

[39] Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA[J]. Nature, 2000,408(6813):740-745.

[40] Rolinski J, Hus I. Immunological aspects of acute and recurrent herpes simplex keratitis[J]. J Immunology Research, 2014,2014:1-9.

[41] Prencipe G, Minnone G, Strippoli R, et al. Nerve growth factor downregulates inflammatory response in human monocytes through TrkA[J]. J Immunol, 2014,192(7):3345-3354.

[42] Datta-Mitra A, Kundu-Raychaudhuri S, Mitra A, et al. Cross talk between neuroregulatory molecule and monocyte: nerve growth factor activates the inflammasome[J]. PLoS One, 2015,10(4):e121626.

[43] Jiang Y, Chen G, Zheng Y, et al. TLR4 signaling induces functional nerve growth factor receptor p75NTR on mouse dendritic cells via p38MAPK and NF-κB pathways[J]. Mol Immunol, 2008,45(6):1557-1566.

[44] Micera A, Stampachiacchiere B, Normando EM, et al. Nerve growth factor modulates toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 and 9 expression in cultured primary VKC conjunctival epithelial cells[J]. Mol Vis, 2009,15:2037-2044.

[45] Takeda S, Miyazaki D, Sasaki S, et al. Roles played by toll-like receptor-9 in corneal endothelial cells after herpes simplex virus type 1 infection[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2011,52(9):6729-6736.

[46] Jin X, Qin Q, Chen W, et al. Expression of toll-like receptors in the healthy and herpes simplex virus-infected cornea[J]. Cornea, 2007,26(7):847-852.

[47] Sarangi PP, Kim B, Kurt-Jones E, et al. Innate recognition network driving herpes simplex virus-induced corneal immunopathology: role of the toll pathway in early inflammatory events in stromal keratitis[J]. J Virol, 2007,81(20):11128-11138.

[48] Zheng M, Klinman DM, Gierynska M, et al. DNA containing CpG motifs induces angiogenesis[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2002,99(13):8944-8949.

[49] Li H, Zhang J, Kumar A, et al. Herpes simplex virus 1 infection induces the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, interferons and TLR7 in human corneal epithelial cells[J]. Immunology, 2006,117(2):167-176.

[50] Wuest T, Austin BA, Uematsu S, et al. Intact TRL 9 and type I interferon signaling pathways are required to augment HSV-1 induced corneal CXCL9 and CXCL10[J]. J Neuroimmunol, 2006,179(1/2):46-52.

[51] Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress-induced immune dysfunction: implications for health[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2005,5(3):243-251.

[52] Wheeler CJ. Pathogenesis of recurrent herpes simplex infections[J]. J Invest Dermatol, 1975,65(4):341-346.

[53] Varnell ED, Kaufman HE, Hill JM, et al. Cold stress-induced recurrences of herpetic keratitis in the squirrel monkey[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 1995,36(6):1181-1183.

[54] Wilcox CL, Johnson EM. Nerve growth-factor deprivation results in the reactivation of latent herpes-simplex virus in vitro[J]. J Virol, 1987,61(7):2311-2315.

[55] Kaplan DR, Miller FD. Neurotrophin signal transduction in the nervous system[J]. Curr Opin Neurobiol, 2000,10(3):381-391.

[56] Hunsperger EA, Wilcox CL. Caspase-3-dependent reactivation of latent herpes simplex virus type 1 in sensory neuronal cultures[J]. J Neurovirol, 2003,9(3):390-398.

[57] Camarena V, Kobayashi M, Kim JY, et al. Nature and duration of growth factor signaling through receptor tyrosine kinases regulates HSV-1 latency in neurons[J]. Cell Host Microbe, 2010,8(6):551.

2017-01-22)

(本文编辑 诸静英)

讣告

Therapeuticeffectsandrelatedmechanismsofnervegrowthfactoronherpessimplexviruskeratitis

LIYue,XUJian-jiang.

DepartmentofOphthalmology,EyeEarNoseandThroatHospitalofFudanUniversity,Shanghai200031,China

XU Jian-jiang, Email: jianjiangxu@126.com

Herpes simplex keratitis (HSK), an important cause of blindness world-wide, is the keratitis caused by herpes simplex viruses. What make doctors feel troublesome are its recurrences and increased resistance to acyclovir. So, looking for alternative drugs is needed. Researches showed that nerve growth factor (NGF) exists in nervous systems as well as other tissues like cornea, and also plays a role as an immunologic mediator. Recently researchers topically used NGF for the treatment of HSK on animal models and patients, getting unexpected great improvement. In this review, the effects of NGF on HSK and the potential mechanisms, including helps of corneal wound healing and corneal nerve regeneration, influence of Toll-like receptor pathways and maintenance of latency, will be discussed and concluded. (Chin J Ophthalmol and Otorhinolaryngol,2017,17:436-440)

Nerve growth factor; Herpes simplex virus keratitis; Corneal wound healing; Corneal nerve regeneration; Toll-like receptors; Virus latency

复旦大学附属眼耳鼻喉科医院眼科 上海 200031

通迅作者:徐建江(Email: jianjiangxu@126.com)

10.14166/j.issn.1671-2420.2017.06.016