婴幼儿肱骨远端骨骺分离对肘关节功能及发育的影响

2017-08-01周维政张立军李连永

周维政 张立军 李连永

. 小儿骨科 Pediatric orthopedics .

婴幼儿肱骨远端骨骺分离对肘关节功能及发育的影响

周维政 张立军 李连永

目的 评价肱骨远端骨骺分离对婴幼儿肘关节功能及发育的影响。方法 回顾性分析从2 0 0 5 年 1 月至 2 0 1 5 年 2 月,我科确诊收治并随访的 1 6 例 ( 1 6 肘 ) 肱骨远端骨骺分离的患儿。所有患儿骨折均为高处跌落致伤,平均受伤年龄 1 8 ( 1 1~3 7 ) 个月;男 1 0 例,女 6 例;左肘 9 例,右肘 7 例;S a l t e r-H a r r i s I 型 3 肘,S a l t e r-H a r r i s I I 型 1 3 肘;1 4 肘患儿骨折移位方向为后内侧,2 肘后外侧移位;6 肘受伤时肱骨小头次级骨化中心未出现;5 肘行切开复位内固定,1 1 肘行闭合复位内固定,其中 1 肘术中应用关节造影辅助闭合复位。最后随访时摄双肘关节正侧位 X 线片及双肱骨正位 X 线片,测量肱骨尺骨角,肱骨远端前倾角及双肱骨全长,并采用梅奥肘关节功能评分 ( m a y o e l b o w p e r f o r m a n c e s c o r e,M E P S ) 对所有患儿双肘进行评价,采用独立与配对样本 t 检验和 χ2检验对肘关节形态发育及功能进行统计分析。结果 1 6 例平均随访 4 2.3 ( 6~9 8 ) 个月,最后随访时肘关节伸直角度患侧平均为 5.9° ( -1 0°~2 2° ),健侧 7.5° ( 3°~1 5° ),P=0.3 3;屈曲角度患侧平均为 1 2 4.4° ( 7 4°~1 3 5° ),健侧 1 3 3.1° ( 1 2 3°~1 4 5° ),P=0.0 1;影像学指标肱骨远端前倾角患侧平均为 4 7.1° ( 2 5°~5 9° ),健侧 5 1.9° ( 3 5°~6 5° ),P=0.0 7 3;肱骨尺骨角平均为 1.2° ( -1 8°~1 4° ),健侧 8.8° ( 2°~1 9° ),P=0.0 0 1;肱骨全长患侧平均为 2 0.7 ( 1 6.0~2 6.3 ) c m,健侧 2 0.3 ( 1 5.5~2 5.8 ) c m,P<0.0 0 1;M E P S 患侧平均为 8 5.6 ( 7 0~9 5 ) 分,健侧 9 5 ( 9 0~1 0 0 ) 分,P<0.0 0 1。肱骨尺骨角分别与骨折复位方式和S a l t e r-H a r r i s 分型差异无统计学意义 ( P=0.5 7,0.2 3 );术后 M E P S 与移位方向、S a l t e r-H a r r i s 分型以及复位方式和肱骨小头次级骨化中心,差异无统计学意义 ( P=1.0 0,0.3 5,1.0 0,0.9 3 )。结论 闭合或切开复位内固定治疗婴幼儿肱骨远端骨骺分离,可获得优良的肘关节功能,但肘内翻畸形为最常见的并发症,术中关节造影下辅助骨折复位,可能有利于减少这一并发症的发生。

肱骨;骨骺分离;婴儿;肘关节;关节造影术;预后

肱骨远端骨骺分离是儿童肘关节损伤较少见的一种类型,常见于 3 岁以下婴幼儿[1],这个时期肘关节周围肌肉等软组织的强度高于肱骨远端的骨与软骨成分,因此,当外力作用于肘关节时,肱骨远端的骨骺与干骺端容易在骺板的肥大细胞层连接处发生移位导致骨骺分离,可伴有或不伴有干骺端骨折[2-4]。由于肱骨远端骨骺尚未完全骨化,因此在X 线片上诊断困难,极易误诊为肘关节脱位及外髁骨折等[5]。该型骨折在不同年龄的损伤原因有所不同,国外报道新生儿及婴儿骨折多由于产伤[6-7]或虐待[1]所致,幼儿受伤机制与伸直型肱骨髁上骨折类似,多有高处坠落病史[8-9]。伤后肘关节在超声、关节造影及磁共振 ( m a g n e t i c r e s o n a n c e i m a g i n g,M R I ) 的辅助下可确诊[6,10-12]。

目前,对肱骨远端骨骺分离的治疗,国外普遍采用闭合复位克氏针内固定的方法;对于预后,多数学者认为该骨折对肘关节运动功能并无较大影响,偶有肘关节屈伸功能明显受限或内外翻畸形的报道,但多局限于小样本及个案报道[11,13-16],系统地进行远期关节功能及影像学评价,未见报道。因此本研究的目的是评价婴幼儿肱骨远端骨骺分离治疗后对肘关节功能及发育的影响。

资料与方法

一、一般资料

收集 2 0 0 5 年 1 月至 2 0 1 5 年 2 月在我科住院治疗的 1 6 例肱骨远端骨骺分离患儿 ( 共 1 6 肘 ) 的病例资料,并进行回顾性分析及随访见表 1。

表1 患儿基本资料Tab.1 Patients information

骨折均为从高处跌落所致,受伤年龄平均为1 8 ( 1 1~3 7 ) 个月;其中男 1 0 例,女 6 例;左肘9 例,右肘 7 例;从受伤到手术的间隔平均为 7 0 ( 5~3 1 2 ) h;新鲜骨折治疗首选闭合复位,当闭合复位失败则改为切开复位,本研究中 5 肘行切开复位克氏针内固定,1 0 肘行闭合复位内固定,1 肘行关节造影辅助下闭合复位克氏针内固定。术后肘关节屈曲 8 0°~9 0° 前臂中立位石膏固定,平均术后 5 ( 4~7 ) 周去石膏并拔出克氏针,开始自主功能锻炼。

二、影像学评价

1. 术前影像学资料:1 6 例患儿的术前肘关节正侧位 X 线片显示,1 0 例肱骨小头次级骨化中心骨化,6 例未骨化;1 4 例骨折后内侧移位,2 例骨折后外侧移位;1 6 例中有 5 例依据肘关节正侧位 X 线片不能明确骨折情况,进一步行 M R I 检查明确诊断( 图 1 )。M R I 影像可见冠状位上肱骨远端骨骺与干骺端轴线异常,且在矢状位上肱骨远端骨骺相对肱骨前缘线后移明显,但桡骨近端与肱骨远端骨骺解剖关系仍正常,如图 1 c、d。按照 S a l t e r-H a r r i s 分型,I 型 3 肘,I I 型 1 3 肘。

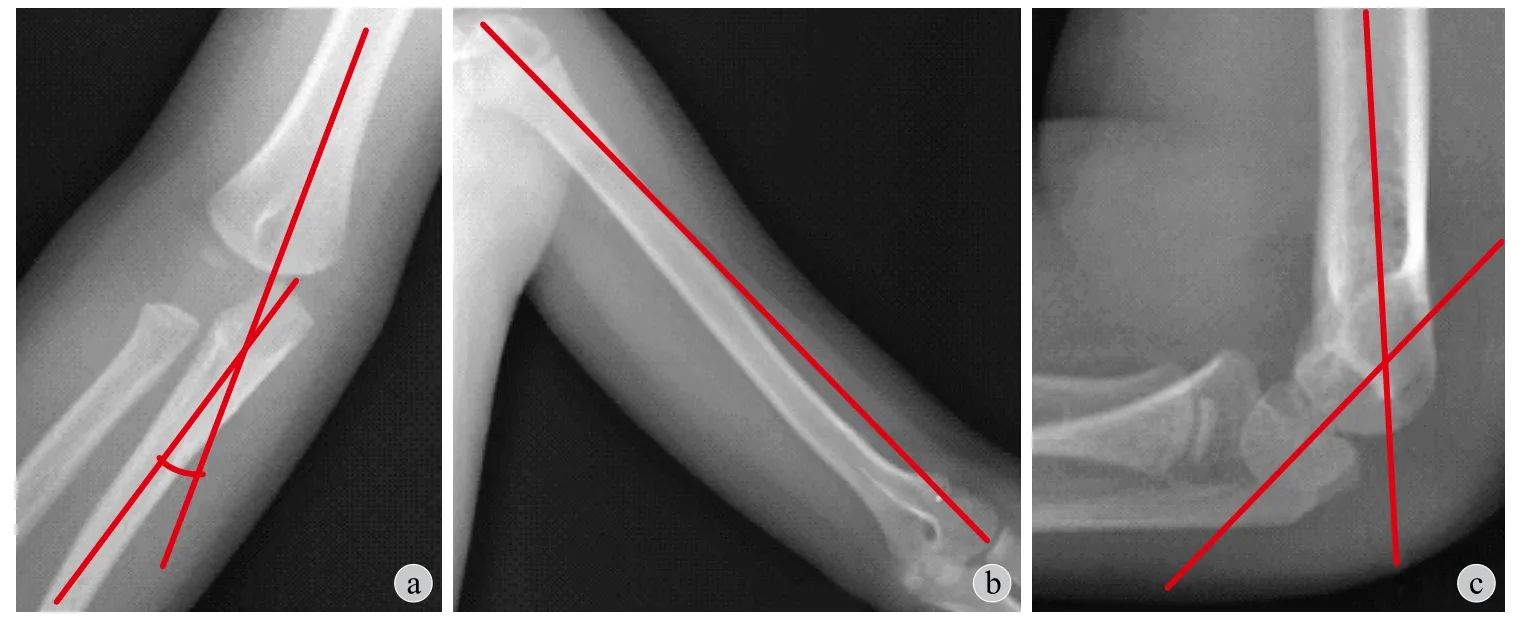

2. 随访时的影像学观测:( 1 ) 肱骨尺骨角的测量:在肘关节正位上测量肱骨轴线与尺骨轴线构成的锐角称为肱骨尺骨角,即提携角,如存在肘内翻,则该角为负值 ( 图 2 a );( 2 ) 肱骨全长的测量:在肱骨全长正位 X 线片上测量肱骨近端关节面顶点至远端肱骨小头关节面顶点的距离作为肱骨全长 ( 图 2 b );( 3 ) 肱骨远端前倾角的测量:在肘关节侧位 X 线片上做肱骨的轴线和肱骨小头次级骨化中心的轴线,二者所成的锐角即为肱骨远端前倾角 ( 图 2 c )。

上述所有测量结果均由同一位医师使用 P A C S系统 ( picture archiving and communication systems,neusoft,中国沈阳 ) 进行测量。每个指标均测量三次,取其平均值。

图1 女,15 个月 a~b:伤后肘关节正侧位 X 线片;c~d:该患儿肘关节 MRI 冠状位 ( c ) 和矢状位 ( d ) 图像 ( H 表示肱骨干骺端,E表示肱骨远端骨骺,R 表示桡骨近端干骺端,U 表示尺骨近端干骺端 )Fig.1 Patient, a 15-month-old girl a - b: The anterioposterior view ( a ) and lateral view ( b ) of the elbow; c - d: Coronary position ( c ) and sagittal position ( d ) of the elbow’s MRI ( H humeral distal metaphysis; E humeral distal epiphysis; R radius proximal metaphysis; U ulnar proximal metaphysis )

图2 肱骨尺骨角,肱骨全长及肱骨远端前倾角测量方法a:肱骨尺骨角的测量方法;b:肱骨全长的测量方法;c:肱骨远端前倾角的测量方法Fig.2 Humeral-ulnar angle, humeral length and humeral shaft-condylar angle measuring methods a: Methods to measure the humeral-ulnar angle; b: Methods to measure the humeral length; c: Methods to measure the humeral shaft-condylar angle

三、功能评价

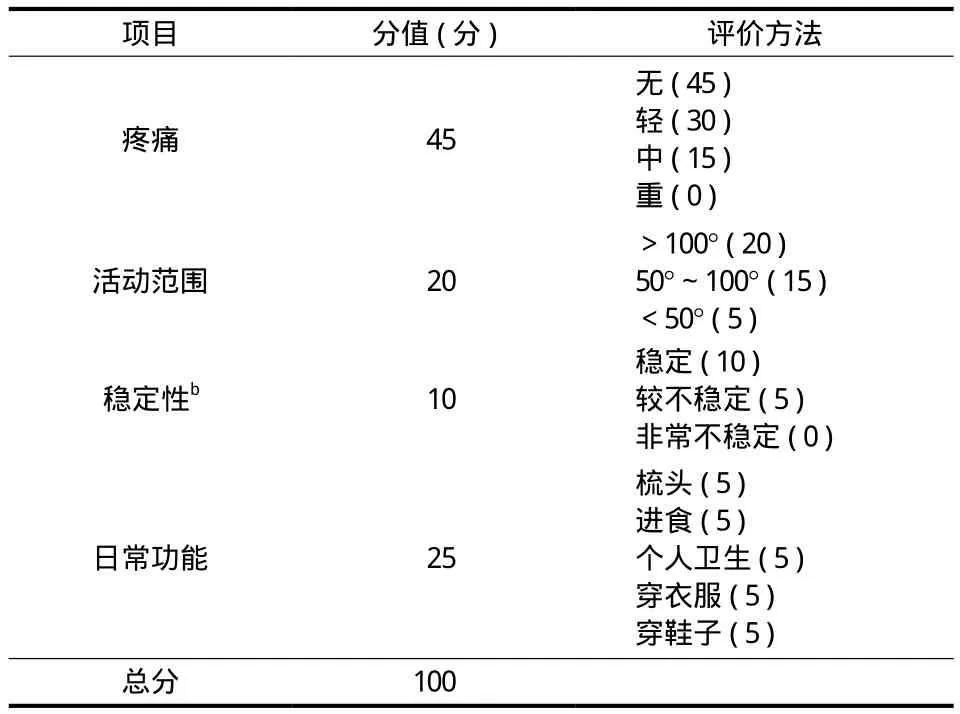

随访时对患儿肘关节屈伸范围进行测量。肘关节伸直角度的测量:前臂旋后 9 0° 位,肘关节最大程度伸直,测量肘关节在矢状面上臂轴线与前臂轴线的夹角,并规定当上臂与前臂轴线位于一条直线时为 0°,正值表示肘关节过伸,负值表示肘关节伸直受限;肘关节屈曲角度的测量:前臂旋后9 0° 位,肘关节最大程度屈曲,测量肘关节在矢状面上臂轴线与前臂轴线所成的夹角。以上操作均由同一位医师使用同一把尺子进行测量。采用梅奥肘关节功能评分量表 ( m a y o e l b o w p e r f o r m a n c e s c o r e,ME P S )[17]分别对疼痛、稳定性、活动范围以及日常功能方面进行评分 ( 表 2 ),依据评分进行评价,优 ( ≥9 0 分 )、良 ( 7 5~8 9 分 )、可 ( 6 0~7 4 分 )、差( <6 0 分 )。

四、统计学处理

所有患儿的正常侧肘关节作为对照,随访时测量的肘屈、伸角度,ME P S 评分以及影像学上测量的肱骨尺骨角、肱骨全长和肱骨远端前倾角双侧比较,采用配对样本 t 检验;采用独立样本 t 检验比较不同复位方式及 S a l t e r-H a r r i s 分型上述各观察指标之间的差异;采用 χ2检验比较 ME P S 分级、复位方式、S a l t e r-H a r r i s 分型与受伤侧别 ( 左或右 )、性别、骨折移位的方向及肱骨小头次级骨化中心是否出现的相关性。所有数据由 S P S S 2 1.0 软件 ( I B M公司,美国纽约 ) 统计完成,显著性水平设定 α=0.0 5。

结 果

1 6 例获 6~9 8 个月随访,平均 4 2.3 个月,所有患儿均无合并神经血管损伤、无切口及针道感染、石膏压疮、骨不连及延迟愈合等并发症发生。

表2 梅奥肘关节功能评分表Tab.2 Mayo elbow performance score scale

一、影像学评价结果

肱骨远端前倾角患侧平均为 4 7.1° ( 2 5°~5 9° ),健侧为 5 1.9° ( 3 5°~6 5° ),P=0.0 7 3;肱骨尺骨角患侧平均值为 1.2° ( -1 8°~1 4° ),健侧为 8.8° ( 2°~1 9° ),P=0.0 0 1,肱骨全长患侧平均为 2 0.7 ( 1 6.0~ 2 6.3 ) c m,健侧为 2 0.3 ( 1 5.5~2 5.8 ) c m,P<0.0 0 1 ( 表 3 );上述测量结果与不同复位方式、S a l t e r-H a r r i s 分型差异均无统计学意义 ( 独立样本 t 检验,P 值为 0.2 3~1.0 0 )。

二、功能评价结果

肘关节伸直角度患侧平均为 5.9° ( -1 0°~2 2° ),健侧平均为 7.5° ( 3°~1 5° ),P=0.3 3;屈曲角度患侧平均为 1 2 4.4° ( 7 4°~1 3 5° ),健侧平均为 1 3 3.1° ( 1 2 3°~1 4 5° ),P=0.0 1;ME P S 患侧平均为 8 5.6 ( 7 0~9 5 ) 分,健侧 9 5 ( 9 0~1 0 0 ) 分,P<0.0 0 1 ( 表 3 )。术后肘关节功能与复位方式、S a l t e r-H a r r i s分型差异无统计学意义 ( 独立样本 t 检验,P 值为0.5 2~0.7 7 );术后 M E P S 优良率与复位方式、S a l t e r-H a r r i s 分型、患儿性别、受伤侧别、手术年龄、移位方向和受伤到手术间隔时间等差异无统计学意义( χ2检验或独立样本 t 检验,P 值为 0.2 6~1.0 0 )。

表3 双肘功能及影像学形态的随访结果 (±s )Tab.3 Clinical and radiogaphic results of bilateral elbow (±s )

表3 双肘功能及影像学形态的随访结果 (±s )Tab.3 Clinical and radiogaphic results of bilateral elbow (±s )

注:配对样本 t 检验N o t i c e: P a i r e d s a m p l e t t e s t

项目 屈曲( ° )伸直( ° ) M E P S ( 分 )肱骨尺骨角 ( ° )肱骨远端前倾角 ( ° )肱骨全长( c m )患侧1 2 4.4±3.5 5.9±1.8 8 5.6±1.8 1.2±2.0 4 7.1±2.1 2 0.7±0.8健侧1 3 3.1±1.5 7.5±0.8 9 5.0±0.7 8.8±1.1 5 1.9±2.5 2 0.3±0.8 t 值 -2.9 -1.0 -5.7 -4.3 -1.9 5.8 P 值 0.0 1 2 0.3 3 2 < 0.0 0 1 0.0 0 1 0.0 7 3 < 0.0 0 1

讨 论

婴幼儿肱骨远端骨骺分离是肱骨远端骨骺损伤中最为少见的一种骨折类型[18],1 8 5 0 年由 S m i t h 首次描述[19]。其损伤机制与伸直型肱骨髁上骨折类似[8-9],少数新生儿可因儿童虐待[6-7]或产伤[1]所致。本研究中 1 6 例均有明确的肘关节外伤史,均为高处坠落伤。但如无明确的外伤史,仍应特别注意儿童虐待及新生儿产生所致的可能性。

肱骨远端骨骺分离是最易漏诊或误诊的一种骨骺损伤类型。肱骨远端的 4 个次级骨化中心中,肱骨小头是最早出现的,多数在生后第 1 年开始骨化[20]。在婴幼儿期,这些骨骺尚未完全骨化,无法在 X 线片上完整显示,给临床诊断带来一定困难[11,13,21],只能通过肱骨远端与尺桡骨近端的相对解剖关系来判断 ( 图 1 a,b )。但当骨折轻微移位时则很难明确诊断,常被漏诊或误诊为肘关节脱位及肱骨内外髁骨折等[1,22],导致延误或错误治疗。本组1 例 ( 例 4 ) 就曾在外院诊断为肘关节脱位,反复多次手法复位失败后转入我院。当肱骨小头次级骨化中心出现后,依据肱骨小头骨骺与干骺端的相对位置,一般可做出正确诊断。

图3 关节造影辅助骨折复位 a:闭合复位前关节造影正位见肱骨远端骨骺向内侧移位;b:侧位可见肱骨远端骨骺向后移位;c~d:闭合复位经皮克氏针内固定观察复位效果Fig.3 Arthrogram-assisting closed reduction a: Arthrogram shows the medial displacement of the humeral distal epiphysis before reduction; b: Arthrogram shows the posterior displacement of the humeral distal epiphysis before reduction; c - d: Arthrogram shows the result of reduction in AP and lateral views

因此,在有肘关节损伤的婴幼儿,肱骨小头骨骺骨化前,如 X 线片表现正常,或无法确定损伤情况,则应通过其它影像学检查进一步明确诊断。1 9 7 9 年,M i z u n o 等[23]通过关节造影证实该骨折是一种关节外的骨折,之后关节造影便成为广泛接受的该骨折的确诊方法[8,10]。但 S u p a k u l 等[11]和 D i a s等[12]则提倡通过超声来诊断,其理由是超声是无创的,不需要镇静,相对于关节造影可操作性强且费用低廉。然而,N i m k i n 等[6]则推荐 M R I 检查,其优点是可以多维成像,可以在不同维度评估骨折的损伤与移位情况,但由于价格昂贵并且需要镇静,其他学者建议 M R I 作为超声检查的补充[24]。

本组所有病例术前均拍肘关节正侧位 X 线片,其中,6 2.5% ( 1 0 肘 ) 肱骨小头次级骨化中心已出现,对正确诊断有重要帮助;有 5 肘通过 X 线片不能明确诊断,进一步完善 M R I 检查,在 T1以及 T2加权序列上可清晰显示肘关节所有的骨性及非骨性成分,可见肱桡关节的解剖关系正常,但肱骨远端骨骺相对于干骺端发生了移位 ( 图 1 c,d )。因此,在 X 线片诊断困难时,更推荐行 M R I 检查。

闭合复位的 1 1 例中 1 肘术中应用关节造影确诊肱骨远端骨骺与干骺端之间的解剖关系异常,并在关节造影下辅助骨折闭合复位 ( 图 3 )。

目前,对于婴幼儿肱骨远端骨骺分离的治疗仍存在诸多争议。对于伤后 8~1 0 天已形成骨痂的骨折,国际上普遍采用保守治疗,主要是避免因复位造成的缺血坏死以及骺板损伤等并发症[11],残余畸形待将来手术矫正。本组 1 例伤后 1 3 天患儿,因影像学上未见明显骨痂生长,进行了切开复位经皮穿针内固定,随访 7 5 个月,未见肱骨远端坏死及骨骺早闭现象的发生;但目前对“陈旧”的肱骨远端骨骺分离是否需行复位治疗,仍缺乏循证证据支持。对于新鲜的婴幼儿肱骨远端骨骺分离的治疗方法也不尽相同。早期曾有学者采用前臂皮肤牵引或手法复位石膏制动治疗[25-26],但骨折复位不完全或骨折再移位在所难免。目前,则多采用全麻下闭合或切开复位,经皮克氏针内固定术治疗一般可获得满意效果[15,22]。

一般认为肱骨远端骨骺分离较肱骨髁上骨折的骨折线位置低,骨折面接触面积大,因此骨折远端发生旋转或内侧倾斜的可能性比肱骨髁上骨折要小[26];但文献报道肘内翻畸形仍是较为常见的并发症,在 D e L e e 等[27]的研究中 1 / 4 ( 4 / 1 6 ) 的患儿伴有 5°~1 0° 的肘内翻畸形,而同样程度的肘内翻畸形在 D e J a g e r 等[28]的报道中达到 3 0%,A b e 等[29]则发现 7 1.4% 的患儿随访时伴有肘内翻,本研究结果也支持远期肘关节提携角丢失为常见的并发症。但目前对肱骨远端骨骺分离治疗后肘内翻发生的原因尚存在争议。T u d i s c o 等[14]对一组病例进行了 3 8 年的随访,发现 1 / 5 的患儿成年后发展为肘内翻畸形,且 4 / 5 的患儿提携角度在随访期间是不断变化的。而 O h 等[22]和 Y o o 等[30]则认为骨折后缺血坏死导致滑车溶解进而导致进行性肘内翻。除此以外,多数学者则认为骨折复位不良是造成肘内翻的主要原因[9,14,23,28-31]。本研究结果表明,在最后随访时患侧提携角较健侧平均丢失 7.6°,其中 6 8.8% 的患儿丢失超过 5°。但本组病例并未发现肘内翻进行性加重或肱骨滑车溶解坏死的现象,因此笔者更支持肘内翻是由骨折移位复位不良所致,良好的骨折复位是避免发生肘内翻的关键。一般认为通过切开直视下骨折复位,可以防止肘内翻的发生,但 J a g e r 等则持相反观点,他认为切开复位也无助于避免发生肘内翻,本研究的数据也支持切开或闭合复位与远期肘关节提携角并不相关。本组中有 1 例 ( 1 肘 ) 在关节造影下闭合复位穿针,在随访时与对侧比较无肘内翻发生。因此,术中肘关节造影辅助下复位,可能有利于避免因复位不足而遗留肘内翻畸形。术中关节造影,除可对骨折情况进行更准确的判断,更重要的是可以清晰显示肱骨远端及尺桡骨近端骨骺的形态,从而可以更准确地观察骨折在冠状面及矢状面上的复位情况,进而避免复位不足。本研究对所有类似骨折均采取关节造影辅助下闭合复位穿针治疗,是否有助于预防肘内翻并发症尚需长期随访观察。

除肘内翻畸形以外,关节活动受限也是较为常见的并发症之一。D e l e e 等[27]研究发现不少于 1 / 3的患儿在屈曲或伸直肘关节时活动受限;并且 M i z u n o等[23]和 D e J a g e r 等[28]研究中均发现超过半数患儿屈伸肘关节活动角度存在 1 0°~2 5° 以内的丢失;但是肘关节活动范围未受影响的报道也常在个案报道中被提及[13,16,21,32]。结合本研究结果,所有患儿最后随访时肘关节屈曲角度患侧较健侧丢失平均为 8.8°,1 8.7% 的患儿丢失角度在 1 0° 以上;肱骨远端前倾角患侧较健侧丢失平均为 4.8° ( P=0.0 7 ),虽然在统计分析结果上并未支持屈曲角度的丢失,这可能与随访样本量偏小有关,但本研究中 3 1.3% 的患儿仍然存在 1 0° 以上的肱骨远端前倾角丢失。本组关节造影辅助复位的病例中,未见明显肱骨远端前倾角的丢失,因此推测术中行关节造影辅助闭合复位,可能也有利于防止残余肱骨远端骨骺后倾畸形。

虽然以往研究发现该骨折预后肘关节功能良好,但之前研究对伤肘仅从外观形态以及活动范围进行评价。而本研究在随访过程中除了对肘关节外观形态以及活动范围进行测量,还首次应用 ME P S对该骨折类型术后肘关节功能进行评价,ME P S 是目前被广泛采用的一种肘关节功能评分量表,由Mo r r e y 等[17]在 1 9 9 2 年提出,评分项目包括疼痛4 5 分,稳定性 2 0 分,关节活动范围 1 0 分以及日常功能 2 5 分,满分 1 0 0 分,最终 4 个项目总分值越高,被测肘关节功能越好,≥9 0 分者肘关节功能为优,7 5~8 9 分为良,6 0~7 4 分为可,<6 0 分为差;其中评价结果为优和良者认为肘关节功能不受影响。在本研究的病例中,1 4 例患儿肘关节功能不受影响,仅有 2 肘最终随访结果为尚可,原因主要是肘关节活动范围的减少,本研究结果显示伤后肘关节存在屈曲功能较健侧肘关节受限约 8.7 5° ( P=0.0 1 2 ),6 2.5% 的患儿肘关节屈曲受限在 5° 以上。虽然肱骨远端前倾角的减小,差异无统计学意义,仍认为屈肘功能的丢失与骨折在矢状位上的复位不足有关。

本研究存在以下局限性:( 1 ) 治疗病例中,得到随访的病例数较少,各分类的亚组例数更少,削弱了统计分析的证据强度;( 2 ) 本研究尚缺乏内固定取出时肱骨尺骨角度的测量值作为本次随访时提携角度是否变化的参考指标;( 3 ) 随访时间较短,因此需要继续随访至患儿骨骼成熟期才能确定患儿目前阶段的肘内翻畸形是否会进展;( 4 ) 本研究采用关节造影的患儿例数少,尚缺乏足够的数据支持关节造影在闭合复位中的作用。

综上所述,闭合或切开复位治疗婴幼儿肱骨远端骨骺分离,可获得优良的肘关节功能结果,但肘内翻畸形为最常见的并发症。

[1]Abzug JM, Ho CA, Ritzman TF, et al. Transphyseal fracture of the distal humerus[J]. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 2016, 24(2):e39-44.

[2]Rockwood CA, Beaty JH, Kasser JR. Rockwood and Wilkins’fractures in children[M]. 7th. Philadelphia, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2010: 561.

[3]Morrey BF, Sanchez-Sotelo J. The elbow and its disorders[M]. 4th. Philadelphia, USA: Elsevier Health Sciences. 2009: 249.

[4]Morrey BF, Sanchez-Sotelo J. The elbow and its disorders[M]. 4th. Philadelphia, USA: Elsevier Health Sciences. 2009: 297.

[5]Herring JA. Tachdjian’s pediatric orthopaedics: from the texas scottish rite hospital for children[M]. 5th. Philadelphia, USA: Elsevier Health Sciences. 2013: 1293.

[6]Nimkin K, Kleinman PK, Teeger S, et al. Distal humeral physeal injuries in child abuse: MR imaging and ultrasonography fi ndings[J]. Pediatr Radiol, 1995, 25(7):562-565.

[7]Hansen M, Weltzien A, Blum J, et al. Complete distal humeral epiphyseal separation indicating a battered child syndrome: a case report[J]. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg, 2008, 128(9): 967-972.

[8]Ruo GY. Radiographic diagnosis of fracture-separation of the entire distal humeral epiphysis[J]. Clin Radiol, 1987, 38(6): 635-637.

[9]Rogers LF, Rockwood CA Jr. Separation of the entire distalhumeral epiphysis[J]. Radiology, 1973, 106(2):393-400.

[10]Yates C, Sullivan JA. Arthrographic diagnosis of elbow injuries in children[J]. J Pediatr Orthop, 1987, 7(1):54-60.

[11]Supakul N, Hicks RA, Caltoum CB, et al. Distal humeral epiphyseal separation in young children:an often-missed fracture-radiographic signs and ultrasound confirmatory diagnosis[J]. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2015, 204(2):W192-198.

[12]Dias JJ, Lamont AC, Jones JM. Ultrasonic diagnosis of neonatal separation of the distal humeral epiphysis[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 1988, 70(5):825-828.

[13]Tharakan SJ, Lee RJ, White AM, et al. Distal Humeral Epiphyseal Separation in a Newborn[J]. Orthopedics, 2016, 39(4):e764-767.

[14]Tudisco C, Mancini F, De Maio F, et al. Fracture-separation of the distal humeral epiphysis. Long-term follow-up of five cases[J]. Injury, 2006, 37(9):843-848.

[15]Kamaci S, Danisman M, Marangoz S. Neonatal physeal separation of distal humerus during cesarean section[J]. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ), 2014, 43(11):E279-281.

[16]Mane PP, Challawar NS, Shah H. Late presented case of distal humerus epiphyseal separation in a newborn[J]. BMJ Case Rep, 2016, 2016.

[17]Morrey BF, Adams RA. Semiconstrained arthroplasty for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis of the elbow[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1992, 74(4):479-490.

[18]Peterson HA. Epiphyseal growth plate fractures[M]. Minnesota, USA: Springer Heidelberg. 2007: 509.

[19]Smith RW. Observations on disjunction of the lower epiphysis of the humerus[J]. Dublin Quarterly J Med Science, 1850, 9(1): 63-74.

[20]Herring JA. Tachdjian’s pediatric orthopaedics: from the Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for children[M]. 5th. Philadelphia, USA: Elsevier Health Sciences. 2013: 6.

[21]Navallas M, Díaz-Ledo F, Ares J, et al. Distal humeral epiphysiolysis in the newborn: utility of sonography and differential diagnosis[J]. Clin Imaging, 2013, 37(1):180-184.

[22]Oh CW, Park BC, Ihn JC, et al. Fracture separation of the distal humeral epiphysis in children younger than three years old[J]. J Pediatr Orthop, 2000, 20(2):173-176.

[23]Mizuno K, Hirohata K, Kashiwagi D. Fracture-separation of the distal humeral epiphysis in young children[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1979, 61(4):570-573.

[24]Brown J, Eustace S. Neonatal transphyseal supracondylar fracture detected by ultrasound[J]. Pediatr Emerg Care, 1997, 13(6):410-412.

[25]Sen RK, Bedi GS, Nagi ON. Fracture epiphyseal separation of the distal humerus[J]. Australas Radiol, 1998, 42(3):271-274.

[26]Moucha CS, Mason DE. Distal humeral epiphyseal separation[J]. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ), 2003, 32(10): 497-500.

[27]DeLee JC, Wilkins KE, Rogers LF, et al. Fracture-separation of the distal humeral epiphysis[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1980, 62(1):46-51.

[28]De Jager LT, Hoffman EB. Fracture-separation of the distal humeral epiphysis[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 1991, 73(1): 143-146.

[29]Abe M, Ishizu T, Nagaoka T, et al. Epiphyseal separation of the distal end of the humeral epiphysis: a follow-up note[J]. J Pediatr Orthop, 1995, 15(4):426-434.

[30]Yoo CI, Suh JT, Suh KT, et al. Avascular necrosis after fractureseparation of the distal end of the humerus in children[J]. Orthopedics, 1992, 15(8):959-963.

[31]McIntyre WM, Wiley JJ, Charette RJ. Fracture-separation of the distal humeral epiphysis[J]. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1984, 188:98-102.

[32]Oda R, Fujiwara H, Ichimaru K, et al. Chronic slipping of bilateral distal humeral epiphyses in a gymnastist[J]. J Pediatr Orthop B, 2015, 24(1):67-70.

Function and development of the elbow after the transphyseal fracture of the distal humerus in infants

ZHOU

Wei-Zheng, ZHANG Li-Jun, LI Lian-Yong. Department of Pediatric Orthopedics, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, Liaoning, 110000, China

LI Lian-yong, Email: loyo_ldy@163.com

Objective To evaluate the function and development of the elbow after the transphyseal fracture of the distal humerus in infants. Methods From January 2005 to February 2015, institutional records of 16 patients ( 16 elbows ) were reviewed retrospectively. These patients were treated in the authors’ institution for the transphyseal fracture of the distal humerus. All the patients were injured by fall from a bed or bicycle. The average age of the patients was 18 months ( range: 11 - 37 months ); 10 of the cases were boys ( 10 elbows ), and 6 were girls ( 6 elbows ); the fracture involved the left elbow in 9 patients ( 56.3% ) and the right elbow in 7 ( 43.7% ). According to the Salter-Harris classif i cation, three ( 18.8% ) lesions were type I, and the others were type II. As for the displacement of the distal fragment, 14 of the 16 lesions ( 87.5% ) were moved posteromedially, and the rest two ( 12.5% ) were posterolaterally; secondary ossif i cation center of capitellum was non-ossifying in 6 elbows. Five ( 31.3% ) patients underwent open reduction and percutaneous pinning, and the other 11 ( 68.7% ) patients were treated with closed reduction and percutaneous pinning. One closed reduction was performed under the assistance of arthrogram. The anteroposterior ( AP ) and lateral radiography of the double elbows and the whole-length anteroposterior ( AP ) radiography of the double humerus were taken at follow-up, the humeral-ulnar angle, the humeral shaft-condylar angle and the humeral length were measured and compared between the injured elbow and the normal. The Mayo Elbow Performance Score ( MEPS ) was used to evaluate the functional outcomes of the elbow. Results All the 16 patientswere followed up for an average of 42.3 months ( range: 6 - 98 months ). For the range of elbow motion, the maximal extension was in average 5.9 degrees on the injured elbow, and 7.5 degrees on the normal ( P = 0.33 ). The maximal fl exion was in average 124.4 degrees on the injured elbow, and 133.1 degrees on the normal ( P = 0.01 ). The humeral shaft-condylar angle on the affected elbow was in average 47.1 degrees ( range: 25 - 59 degrees ) , and that was 51.9 degrees ( range: 35 - 65 degrees ) on the normal side, P = 0.073. The average humeral-ulnar angle was 1.2 degrees ( range: -18 - 14 degrees ) on the injured elbow, and 8.8 degrees ( range: 2 - 19 degrees ) on the normal side, P = 0.001. The average humeral length was 20.7 cm ( range: 16.0 - 26.3 cm ) on the injured size, and 20.3 cm ( range: 15.5 -25.8 cm ) on the normal size, P < 0.001. The MEPS was in average 85.6 points ( range: 70 - 95 points ) on the involved side, and 95 points ( range: 90 - 100 points ) on the uninvolved side, P < 0.001. There were no statistical differences in the humeral-ulnar angle ( P = 0.57, 0.23 ) when compared the reduction procedures and the Salter-Harris classif i cation. MEPS was not related to the displacement ( P = 1.00 ), Salter-Harris classif i cation ( P = 0.35 ) and reduction procedures ( P = 1.00 ) and ossifying of capitellum secondary ossif i cation center ( P = 0.93 ). Conclusions For the transphyseal fracture of the distal humerus in infants, an excellent functional outcome is expected when treated with closed or open reduction and percutaneous pinning. However, it should be kept in mind that residual cubitus varus is a frequently seen complication. Further investigations should focus on whether the intraoperative arthrogram is helpful to avoid cubitus varus.

Humerus; Epiphysiolysis; Infant; Elbow Joint; Arthrography; Prognosis

10.3969/j.issn.2095-252X.2017.07.002

R726.8, R683

2017-03-27 )

( 本文编辑:李慧文 )

1 1 0 0 0 0 沈阳,中国医科大学附属盛京医院小儿骨科

李连永,E m a i l: l o y o_l d y@1 6 3.c o m